Case Vignette

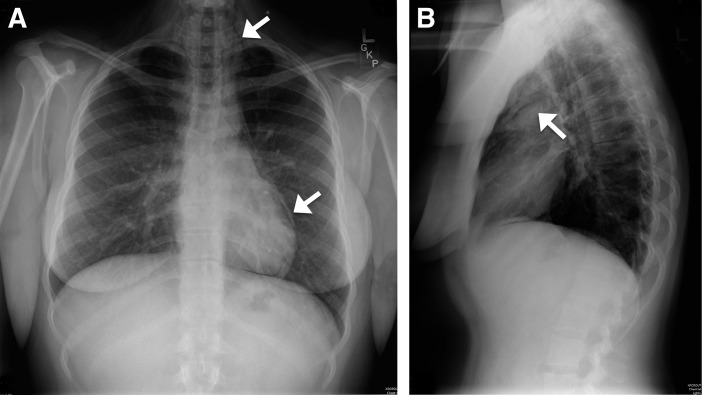

A 22-year-old woman presented to a local emergency room with chest pain that began 30 minutes earlier in the course of performing forceful fellatio. She had a past medical history of mild persistent asthma and denied alcohol consumption, smoking, or the use of illicit drugs. She denied cough, vomiting, or shortness of breath. Vital signs were normal and she was afebrile. On examination, she appeared well-nourished and nontoxic. Cervical crepitus was present. Heart and lung auscultation was normal, as was examination of her oropharynx. Chest radiographs were obtained in posteroanterior and lateral views (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Posteroanterior and (B) lateral view chest radiographs. Air tracking in mediastinal and cervical tissue planes is diagnostic of pneumomediastinum (arrows).

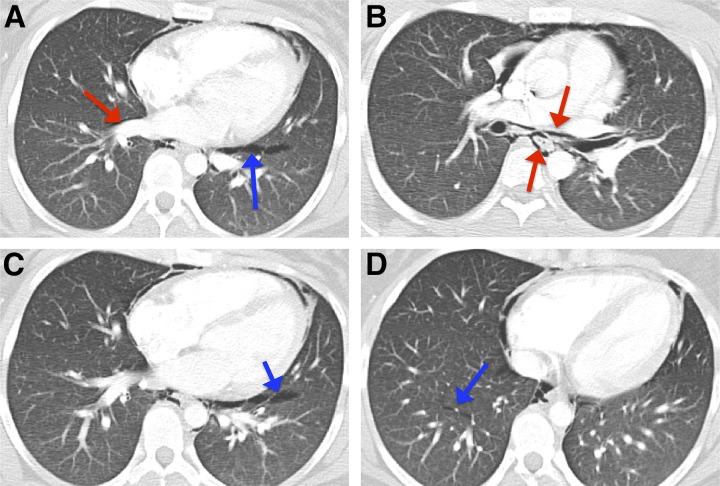

The findings prompted the acquisition of computed tomography (CT) of the chest with intravenous contrast (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Contrasted computed tomography of the chest. (A) Selected slice demonstrating pneumomediastinum, pulmonary interstitial emphysema (blue arrow), and air tracking along bronchovascular bundles into the hila (red arrow), consistent with the Macklin effect. (B–D) Similar findings are observed in multiple sites bilaterally.

The patient was given analgesics, broad-spectrum antibiotics, a proton pump inhibitor, and was transferred to a tertiary referral center for subspecialty management of her condition.

Questions

1. What is the name of the radiographic findings seen on chest imaging?

2. What is the pathophysiological mechanism of this condition?

Discussion

The term “pneumomediastinum” denotes the presence of air in mediastinal tissue planes. This condition can cause retrosternal chest pain, dyspnea, altered vocal quality, and/or odynophagia. On examination, it can be occult or manifest as subcutaneous emphysema of tissues of the neck and thorax.

When pneumomediastinum is clinically suspected, simple posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs are the first step in diagnosis. This shows air surrounding mediastinal structures, such as the heart and great vessels that may track into subcutaneous planes. Computed tomography imaging of the chest is the next diagnostic step when the underlying mechanism is unclear, as this often elucidates the underlying etiology (i.e., the origin of the air), which is key to management.

Pneumomediastinum occurs generally by leakage of air from an aerated viscus that traverses or abuts the mediastinal plane (i.e., esophageal, laryngotracheal, or alveolar tissue). More rarely, primary mediastinal infections with gas-producing organisms can also present with pneumomediastinum, but this most often occurs after a sternotomy and is generally clinically obvious. Lacerations of the laryngotrachea are also usually clinically apparent; these most commonly occur after procedural interventions, such as endotracheal intubation, but can occur with invasive tumors or inhaled foreign objects. However, esophageal injury (Boerhaave syndrome) and pneumomediastinum from alveolar rupture (spontaneous pneumomediastinum or SPM) can be difficult to distinguish by history and require very different management approaches. This is because pneumomediastinum from esophageal and alveolar sources both can occur after profound intrathoracic pressure changes or Valsalva maneuvers, such as occur with severe vomiting or coughing spells. However, the clinical presentation of Boerhaave syndrome will include findings consistent with sepsis; significant hemoconcentration is seen in about half of cases. This condition can also present with a left pleural effusion, air–fluid levels in the mediastinum, and/or radiographic evidence of esophageal injury. Antimicrobial therapy is indicated when Boerhaave syndrome is suspected or confirmed.

Although alveolar tissue is not directly contiguous with the mediastinum, alveolar rupture causes SPM via air dissection up the bronchovascular bundles through the hilum into the mediastinum (a mechanism known as the Macklin effect, after its initial description by C. C. Macklin in 1939). This develops in predisposed individuals under conditions of thoracic pressure cycling and has been described to occur in diverse contexts, including positive pressure ventilation, childbirth, the smoking of crack cocaine, and SCUBA diving. Underlying pulmonary disease, especially asthma (which is present in about a quarter of cases) predisposes to alveolar rupture and is an important risk factor; ethanol intoxication, malnutrition, and male sex have also been associated with SPM. SPM can also be associated with paraseptal emphysema and has been known to recur or to presage development of spontaneous pneumothorax, although this is exceedingly rare.

The term SPM is used (here and in most texts) to describe this subtype of pneumomediastinum caused by the Macklin effect. PIE (i.e., the presence of air in the pulmonary interstitium) is a finding that strongly suggests the Macklin effect/SPM when seen on imaging. PIE is not always observed in SPM, but case series report that it is detectable on computed tomography images in the majority (50–89%) of cases. PIE will appear as air-density areas (often linear or lenticular in shape) tracking along the bronchovascular bundles, the visceral pleura, and/or interstitial septa (Figure 2). Importantly, in the singular circumstance of severe blunt force trauma, the presence of PIE is not sufficient to exclude other causes of pneumomediastinum, as injuries to multiple aerated intrathoracic organs can coexist. However, in clinically compatible cases (i.e., pneumomediastinum without severe blunt force trauma or signs/symptoms of Boerhaave syndrome), the presence of PIE secures the diagnosis of SPM and obviates more aggressive workup or management strategies.

SPM is benign and self-limited, with an excellent prognosis. Brief observation is recommended, and no follow-up imaging is considered routinely necessary. If Boerhaave syndrome or laryngotracheal injury remain diagnostic considerations on clinical grounds (such as when findings of sepsis are present or a recent tracheal procedure was performed), a contrasted swallow study and/or endoscopic evaluation may still be necessary but is not routinely performed.

Answers

1. What is the name of the radiographic findings seen on chest imaging?

Pneumomediastinum with radiographic evidence of pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) consistent with the Macklin effect

2. What is the pathophysiological mechanism of this condition?

Alveolar rupture leads to air leakage into the pulmonary interstitium, where it dissects along the bronchovascular bundle into the pulmonary hilum, entering the mediastinum.

Follow-Up

A pulmonary consultation was obtained and imaging was carefully reviewed. As PIE consistent with the Macklin effect could be seen in both lower lobes (Figure 2), a diagnosis of SPM was reached. Although proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics had been started at the referring facility out of concern for Boerhaave syndrome, these were discontinued, and expectant management was recommended. The patient was observed overnight uneventfully and discharged home with analgesics. The patient was instructed to follow up with her primary care provider for a repeat plain film radiograph of the chest in 1 week but was lost to follow-up at our institution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Benjamin Tillman for his generous assistance with figure design.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant T32HL105346-07 (D.W.R.).

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Recommended Reading

- Kim KS, Jeon HW, Moon Y, Kim YD, Ahn MI, Park JK, et al. Clinical experience of spontaneous pneumomediastinum: diagnosis and treatment. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:1817–1824. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, Morera R, Escobar I, Saumench J, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin C. Transport of air along pulmonic blood vessels from alveoli to mediastinum: clinical implications. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 1939;64:913–926. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai M, Murayama S, Gibo M, Akamine T, Nagata O. Frequent cause of the Macklin effect in spontaneous pneumomediastinum: demonstration by multidetector-row computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:92–94. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000187416.07698.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermark M, Schnyder P. The Macklin effect: a frequent etiology for pneumomediastinum in severe blunt chest trauma. Chest. 2001;120:543–547. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.2.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.