Abstract

Rationale: The relationship between respiratory function at hospital discharge and the severity of later respiratory disease in extremely low gestational age neonates is not well defined.

Objectives: To test the hypothesis that tidal breathing measurements near the time of hospital discharge differ between extremely premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) or respiratory disease in the first year of life and those without these conditions.

Methods: Study subjects were part of the PROP (Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program) study, a longitudinal cohort study of infants born at less than 29 gestational weeks followed from birth to 1 year of age. Respiratory inductance plethysmography was used for tidal breathing measurements before and after inhaled albuterol 1 week before anticipated hospital discharge. Infants were breathing spontaneously and were receiving less than or equal to 1 L/min nasal cannula flow at 21% to 100% fraction of inspired oxygen. A survey of respiratory morbidity was administered to caregivers at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months corrected age to assess for respiratory disease. We compared tidal breathing measurements in infants with and without BPD (oxygen requirement at 36 wk) and with and without respiratory disease in the first year of life. Measurements were also performed in a comparison cohort of term infants.

Results: A total of 765 infants survived to 36 weeks postmenstrual age, with research-quality tidal breathing data in 452 out of 564 tested (80.1%). Among these 452 infants, the rate of postdischarge respiratory disease was 65.7%. Compared with a group of 18 term infants, PROP infants had abnormal tidal breathing patterns. However, there were no clinically significant differences in tidal breathing measurements in PROP infants who had BPD or who had respiratory disease in the first year of life compared with those without these diagnoses. Bronchodilator response was not significantly associated with respiratory disease in the first year of life.

Conclusions: Extremely premature infants receiving less than 1 L/min nasal cannula support at 21% to 100% fraction of inspired oxygen have tidal breathing measurements that differ from term infants, but these measurements do not differentiate those preterm infants who have BPD or will have respiratory disease in the first year of life from those who do not.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01435187)

Keywords: wheezing, respiratory inductance plethysmography, pulmonary function tests, oximetry, premature

Premature birth is associated with impaired lung function that can persist into adulthood (1). Wheezing, cough, and hospitalization for respiratory illnesses all occur more frequently in children born preterm than in those born at term (2). Although bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a risk factor for more severe respiratory problems, infants without BPD also experience substantial respiratory morbidity (3). Despite the high prevalence of respiratory problems in preterm children, there is a paucity of data regarding the physiologic mechanisms of post-prematurity respiratory disease.

Premorbid respiratory function among infants born at term is an independent predictor of wheezing and asthma in infancy and early childhood (4–8). Infant pulmonary function tests (PFTs) performed in preterm infants between 36 and 40 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA) have shown decreased expiratory flows, reduced functional residual capacity (FRC), increased airway resistance, and decreased lung compliance (9–12). However, most studies using infant PFTs in preterm infants had small sample sizes and limited prospective follow-up data, making it difficult to establish an association between lung function near the time of discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and subsequent respiratory problems.

The raised volume rapid thoracoabdominal compression technique allows infant PFTs to be performed in infants, yielding results that are comparable to conventional PFTs in cooperative subjects (13). However, the time and sedation risk involved in performing infant PFTs preclude its use in studying large cohorts and in clinical assessment. Tidal breathing analysis allows assessment of respiratory function without sedation (14) and can be performed in the NICU. In full-term infants, abnormal tidal breathing measurements in early infancy are an independent risk factor for wheezing and asthma in later life (5, 6), but limited data are available regarding the association of these physiologic measurements with clinical outcomes in preterm infants.

We hypothesized that tidal breathing measurements in extremely preterm infants near the time of hospital discharge would differentiate between infants with BPD and those without BPD and be predictive of which infants would develop respiratory morbidity in the first year of life. To test this hypothesis, we measured tidal breathing variables in a large cohort of extremely preterm infants and assessed their BPD status before discharge and respiratory morbidity in the first year of life.

Methods

Study Subjects

Infants in this study were enrolled in the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP; www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT01607216), a multicenter, longitudinal birth cohort study of extremely low gestational age (GA) neonates. Details of the design of the PROP study have been reported (15). The PROP study network consisted of five clinical research sites located across the United States and one data coordinating center. Each center enrolled between 105 and 184 infants born at less than 29 weeks GA. Parental consent was obtained before enrollment. Detailed, daily clinical data were prospectively collected while in the hospital, and tidal breathing measurements were obtained 1 week before anticipated discharge from the NICU. BPD was defined using a modification of the criteria proposed by Shennan and colleagues (16–18). Infants were classified as having BPD if they needed supplemental O2 at 36 weeks PMA; they were classified as “no BPD” if they were in room air at 36 weeks PMA or discharged home in room air before 36 weeks PMA.

After discharge, families were contacted by phone at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months for a questionnaire assessing respiratory morbidity (18). There are no validated, consensus definitions of respiratory morbidity in preterm infants. Previous studies of respiratory outcomes of prematurity have used a variety of measures, each of which may have its own associated biases (3, 18, 19). For example, a history of wheezing may be affected by recall bias, whereas medication use and hospitalization may be affected be socioeconomic factors and access to health care. With this background in mind, the PROP developed a composite measure of postdischarge respiratory morbidity as its primary outcome (18, 19). Infants were classified as having postdischarge respiratory disease in the first year of life, if their caregivers reported a positive response in one of four domains on two or more survey encounters. The four domains consisted of respiratory medications, hospitalization for respiratory causes, respiratory symptoms, and respiratory technology use. We also defined secondary outcomes by the severity of respiratory disease on the basis of hospitalization, supplemental oxygen therapy, or mechanical ventilation (18).

The PROP protocol was approved by local institutional review boards at each of the clinical research sites and the PROP Observational Study Monitoring Board. Parents of the PROP enrollees and the full-term comparison infants provided written informed consent for all study procedures, including tidal breathing analyses.

Tidal Breathing Measurements

The BioCapture physiologic monitoring system (Great Lakes Neurotech) was used to make tidal breathing measurements by respiratory inductance plethysmography (RIP). Infants were excluded from RIP if they were receiving greater than or equal to 1 L/min of nasal cannula flow (fraction of inspired oxygen, 0.21–1.0) or had a condition that prevented placement of inductance bands around the chest or abdomen. They were excluded from RIP if they were being supported with continuous positive airway pressure or mechanical ventilation. The scalar RIP tracings captured rib cage and abdominal motion. Continuous pulse oximetry was also simultaneously recorded with an oximeter connected to the BioCapture system. The oximeter had an effective averaging time of 1.5 to 3.0 seconds, depending on the pulse rate (NONIN Medical, Inc.). Infants were studied in the supine position and 30 minutes or more after their last feeding. Nasogastric tubes were removed, if possible. Quiet sleep was behaviorally defined by eyes closed, regular breathing, and no fluttering of eyelids or limbs (20). Sleep state was assessed and documented every 3 minutes, and only data from behaviorally determined quiet sleep were analyzed. Fifteen to 30 minutes of RIP data were collected, after which infants received 1.25 mg of albuterol by small volume wet nebulizer. An additional 15 minutes of data were collected 10 minutes after the nebulization treatment was completed. Albuterol was not administered if the parent refused or if there was a medical contraindication to β-agonists (e.g., supraventricular tachycardia).

Although the primary objective of our study was to assess the relationship between tidal breathing measurements and pulmonary outcomes in preterm infants, we obtained data from a small cohort of 18 healthy term infants at 1 to 3 days of life as a comparison group. The infants were recruited from three PROP sites (Rochester/Buffalo, Indiana University, and Vanderbilt University). Their mean PMA at testing was 39.5 weeks (standard deviation [SD], 1.3 wk; range, 36–41 wk), and the mean birth weight was 3,289 g (SD, 362 g). We did not administer albuterol to the term comparison cohort.

RIP Data Analysis

RIP data were analyzed as previously reported (21, 22). Individuals assessing RIP data were blinded to BPD and postdischarge respiratory disease status. Five representative epochs of quiet sleep were selected for analysis, and descriptive statistics for RIP values were calculated. To account for variability in breathing patterns, a minimum of 30 breaths was used for analysis (23, 24). Selected breaths demonstrated a stable end-expiratory volume and regular rhythmic motion consistent with quiet sleep on the scalar tracings and a closed tracing when viewed on a Konno-Mead plot with no “figure of eight” loops (14). Rib cage and thoracic excursion were internally calibrated to each other using the quantitative diagnostic calibration technique (25). Because we did not make absolute measurements, such as tidal volume, external calibration to a known volume was not necessary and was not performed (14). To assess agreement when selecting research quality breaths, we compared analyses from two independent observers using data from 32 infants and found the intraclass correlation coefficient to be 0.95.

Vivosense software (Vivonoetics, Ventura, CA) was used to analyze the RIP data. The RIP-derived measurements included respiratory rate, phase angle, the ratio of time to peak expiratory flow over total expiratory time (Tpef/Te), and percent contribution of the rib cage to inspiratory tidal volume (%RCi) (14). Phase angle (PA) reflects the relative synchrony between the rib cage and abdominal compartments during tidal breathing, and it is elevated with increased airway resistance or decreased lung compliance (26). Tpef/Te is smaller in individuals with obstructive lung disease and is a predictor of infantile wheezing and future asthma diagnosis (5, 6, 27, 28). A lower %RCi is, most often, a reflection of increased chest wall compliance (14, 29).

Oxygenation and Desaturations with Brief Respiratory Pauses during Sleep

A higher number of mild desaturations with brief respiratory pauses during sleep are associated with a lower FRC (30). We analyzed breathing patterns and simultaneous pulse oximetry during epochs of behaviorally determined quiet sleep, as above. The number of desaturation episodes with an absolute fall in oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2) % by 4 during an apnea that lasted at least 4 seconds was counted and normalized for the number of minutes of quiet sleep for each infant. Apneas were identified from the scalar RIP tracings. If an infant had no 4-second apneas linked to desaturation by 4%, the longest apnea without a desaturation by 4% was identified (an apnea with stable SpO2%). This assessment allowed us to characterize all infants, including those who had the ability to avoid developing hypoxemia with short apnea. Infants having a 4% desaturation within 10 seconds of a 4-second apnea were further described by how fast their SpO2% fell during the apnea, using the percentage fall per second of apnea. This value, in particular, is inversely correlated with FRC (30). The lowest SpO2% (SpO2% nadir) was also recorded.

Training and Quality Control

Before initiation of the study, research personnel who performed tidal breathing studies at all the study sites attended a training meeting, where they reviewed how to perform the tests uniformly. Before any subjects were enrolled, each site was required to demonstrate the ability to perform at least five tidal breathing studies on infants that met the research-quality criteria described above. Once enrollment was initiated, site visits were performed to ensure proper test procedures. A shared manual for standard operating procedures for tidal breathing measurements was used at all sites. All studies were reviewed at the central over-reading center located at Riley Hospital for Children, and only studies that met research-quality criteria were used for analysis. Ongoing quality control feedback was provided to the sites, indicating why studies were unacceptable, and every study site was continuously monitored for rate of unacceptable studies and changes in study personnel. Additional on-site training and/or conference calls with study investigators (C.L.R. and J.S.K.) were conducted as needed to maintain quality.

Statistical Analysis

Infant demographics at birth and at the time of testing, clinical status at the time of testing, and each domain of postdischarge respiratory disease (hospitalization, symptoms, medication use, and technology use) were summarized as proportions, mean and SD, or median and interquartile range. For each subject with more than 30 breaths, the median value of each measurement was calculated as a summary value to be included in the statistical analysis. The data were compared between infant with and without postdischarge respiratory disease using Pearson chi-square test, Cochran-Armitage trend test, two-group t test, or Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for median differences using the bootstrap method (31). Two-group t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test were also used to compare baseline prebronchodilator tidal breathing measurements between BPD and non-BPD groups. To assess whether tidal breathing measurements were predictive of postdischarge respiratory disease in preterm infants with more severe lung disease, we analyzed the data from infants with BPD as a subgroup.

For each infant with both pre- and post-bronchodilator RIP data available, we assessed the infant’s bronchodilator response (BDR) by comparing the mean of all values of a particular RIP measure from the prebronchodilator breaths to the mean from the post-BD breaths. BDR was defined as a mean decrease in phase angle or increase in Tpef/Te from baseline larger than the pooled SD (32). To study the relationship between BDR and postdischarge respiratory disease, the proportion of infants with BDR who had postdischarge respiratory disease was compared with those without using a chi-square test.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute).

Results

Of the 765 infants from the PROP cohort who survived to 36 weeks PMA, tidal breathing measurements were made in 564 (73.7%) available eligible and consenting infants of the total cohort (Table 1). Compared with the entire PROP cohort, the infants in this study tended to have a higher GA and were more likely to be white (18). Infants who did not have tidal breathing measurements were born at a slightly lower GA (26.9 vs. 26.2 wk, P < 0.001), had lower birth weight (947 vs. 842 g, P < 0.001), and were more likely to have BPD (36.8% vs. 54.9%, P < 0.001) (see Table E1 in the online supplement). Of the infants who had tidal breathing measurements, 348 (61.7%) had postdischarge respiratory disease and 189 (33.5%) did not; there were 27 infants (4.8%) who did not have enough postdischarge data to assess respiratory disease status. A flow diagram of the derivation of our study cohort is available online (Figure E1). The most common reasons for no measurements were ineligibility for study on the basis of level of respiratory support, parent refusal, and transfer to an outside hospital before 34 weeks PMA. Most (63.8%) infants were on no respiratory support, and the mean PMA at time of testing was 37.4 + 1.9 weeks. Compared with term infants, PROP infants demonstrated greater thoracoabdominal asynchrony (difference between PROP and term cohort phase angle −65.1°; 95% CI, −71.4° to −58.8°), decreased %RCi (mean difference, 23.1%; 95% CI, 15.1–31.1%), and more frequent oxyhemoglobin desaturations (mean difference, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21–0.44) (Table E2).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort

| No Postdischarge Respiratory Disease (n = 189) | Postdischarge Respiratory Disease (n = 348) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 80 (42.3) | 188 (54.0) |

| Race | ||

| White | 131 (69.3) | 194 (55.7) |

| Black/African American | 47 (24.9) | 138 (39.7) |

| Asian | 8 (4.2) | 4 (1.1) |

| Others | 3 (1.6) | 12 (3.4) |

| Gestational age, wk | 27.0 (1.3) | 26.8 (1.4) |

| Multiple births | 63 (33.3) | 76 (21.8) |

| Twins, n | 52 | 66 |

| Triplets or quadruplets, n | 11 | 10 |

| Birth weight, g, mean (SD) | 972.5 (232.9) | 933.3 (225.2) |

| PMA at test, wk, mean (SD) | 37.1 (1.8) | 37.5 (2.0) |

| Weight at test, g, mean (SD) | 2,491.0 (462.6) | 2,504.5 (486.5) |

| Level of support at test | ||

| No respiratory support | 152 (80.4) | 190 (54.6) |

| Nasal cannula ≤ 1 L/min | 37 (19.6) | 158 (45.4) |

| Nasogastric tube in place during test | 42 (22.2) | 63 (18.1) |

| On caffeine during test | 6/180 (3.3) | 12/326 (3.7) |

| BPD (modified Shennan) | 50/188 (26.6) | 145/342 (42.4) |

| PMA at discharge, wk, mean (SD) | 38.8 (2.9) | 39.7 (3.8) |

| Hospitalizations in Year 1 | ||

| 0 | 173/185 (93.5) | 220/335 (65.7) |

| 1 | 11/185 (5.9) | 74/335 (22.1) |

| ≥2 | 1/185 (0.5) | 41/335 (12.2) |

| Symptom in Year 1 | ||

| Frequent wheeze or cough, with inhaled steroids, for ≥6 mo | 0 | 33/343 (9.6) |

| Frequent wheeze or cough for ≥6 mo | 0 | 244/343 (71.1) |

| None | 187/187 (100.0) | 66/343 (19.2) |

| Medication use in Year 1 | ||

| System steroids or pulmonary vasodilator | 8/189 (4.2) | 76/345 (22.0) |

| Inhaled steroids bronchodilator | 6/189 (3.2) | 118/345 (34.2) |

| None | 175/189 (92.6) | 151/345 (43.8) |

| Technology use in Year 1 | ||

| Home oxygen after Month 6 or mechanical ventilation | 1/189 (0.5) | 61/344 (17.7) |

| Home oxygen use at Month 3 or tracheostomy | 13/189 (6.9) | 53/344 (15.4) |

| None | 175/189 (92.6) | 230/344 (66.9) |

Definition of abbreviations: BPD = bronchopulmonary dysplasia; PMA = postmenstrual age; SD = standard deviation.

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise noted.

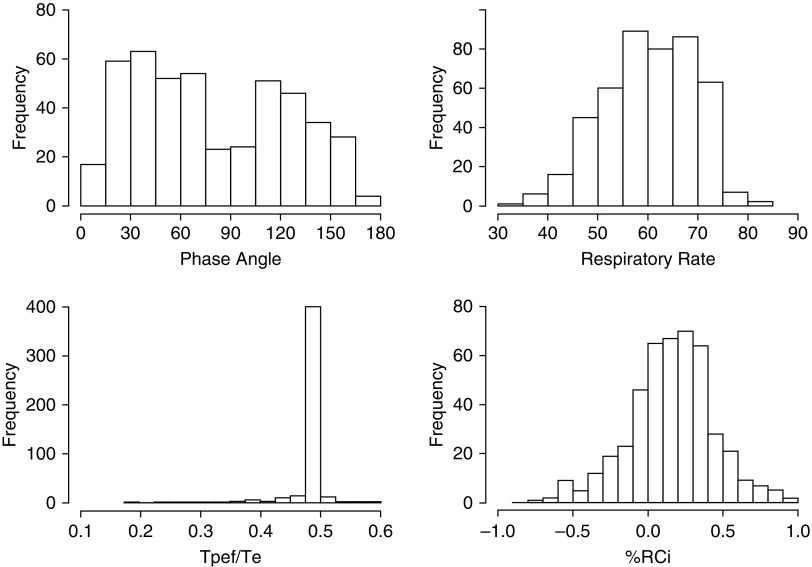

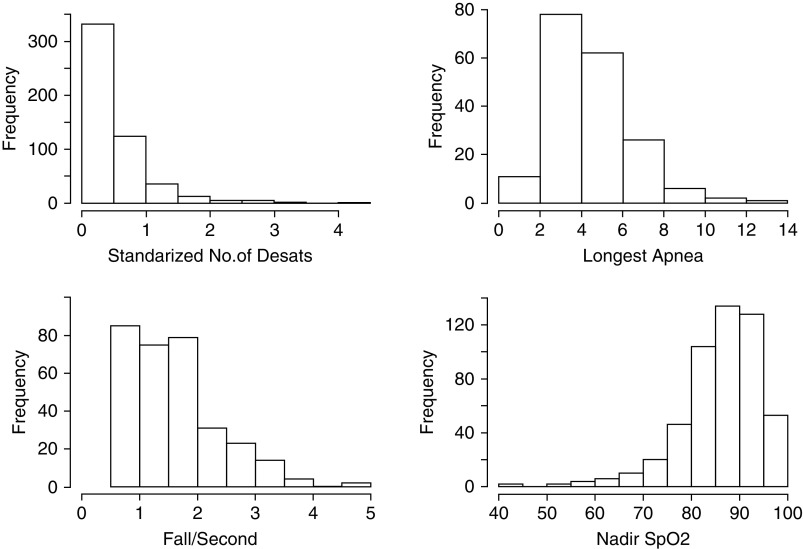

The distribution of different RIP measurements for the PROP cohort is shown in Figure 1. Respiratory rate (RR) and %RCi were normally distributed, but PA had a bimodal distribution for the preterm infants. Tpef/Te was tightly clustered around 0.49. The distribution of sleep oximetry with RIP measurements is shown in Figure 2. In general, infants had less than one spontaneous desaturation by greater than or equal to 4% per minute of quiet sleep, those tolerating longer than 4-second apneas without 4% desaturation could do so for as long as 8 seconds, and most infants with a fall in SpO2% by 4% had falls by 2%/s of apnea, or less, although some had quite precipitous falls in SpO2%. The nadir of SpO2% tended to be greater than 80%.

Figure 1.

Frequency histograms for respiratory inductance plethysmography measurements. %RCi = percent contribution of the rib cage to inspiratory tidal volume; Tpef/Te = ratio of time to peak expiratory flow over total expiratory time.

Figure 2.

Frequency histograms for sleep oximetry measurements. Desat = desaturation; SpO2 = oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry.

Tidal breathing measurements in infants with BPD are compared with those without BPD in Table 2. There was a small but statistically significant difference in Tpef/Te between infants with BPD compared with those without BPD, with Tpef/Te being smaller in the BPD group (mean difference, 0.01; 95% CI, 0.00–0.01). The number of desaturations per second was lower in the non-BPD groups compared with the BPD group, and the longest apnea without desaturation was longer in the non-BPD group compared with the BPD group. There were no other significant differences in infants with and without BPD in any RIP tidal breathing measurements or results on the basis of oximetry. We did not observe any consistent, clinically significant associations between any other clinical variables related to NICU stay (e.g., days on mechanical ventilation) and any tidal breathing measurements, except that lower birthweight was associated with a higher respiratory rate.

Table 2.

Tidal breathing measurements in infants with and without bronchopulmonary dysplasia

| Tidal Breathing Measurements | No. | No Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia* | Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia* | Mean or Median Difference (95% CI†) | P Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIP | |||||

| Phase angle, degrees | 429 | 77.4 ± 45.1 | 81.5 ± 45.9 | 4.0 (−4.8 to 12.9) | 0.37 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 429 | 60.1 ± 7.9 | 61.0 ± 10.4 | 1.0 (−0.8 to 2.7) | 0.28 |

| Tpef/Te | 429 | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | −0.009 (−0.015 to −0.003) | <0.01 |

| %RCi | 429 | 0.16 ± 0.27 | 0.16 ± 0.31 | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.05) | 0.77 |

| Sleep oximetry (room air only) | |||||

| No. of desaturations ≥4%/s | 260 | 0.42 (0.18 to 0.82) | 0.61 (0.35 to 0.88) | 0.19 (0.05 to 0.36) | 0.03 |

| Longest apnea, s | 66 | 4.5 (3.5 to 5.5) | 3.2 (2.5 to 3.3) | −1.4 (−1.6 to −0.9) | 0.03 |

| Fall in O2 saturation/s, % | 188 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.2) | 0.69 |

| Lowest SpO2, % | 255 | 87.5 (83.0 to 91.0) | 85.0 (82.5 to 88.0) | −2.5 (−4.0 to 1.0) | 0.17 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; RCi = contribution of rib cage expansion to inspiratory tidal volume; RIP = respiratory inductance plethysmography; SD = standard deviation; SpO2 = oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry; Tpef/Te = ratio of time to peak expiratory flow over total expiratory time.

Data presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range).

95% CIs of median differences obtained through bootstrap method (31).

t test with equal variance or Wilcoxon test.

There were no significant differences in prebronchodilator tidal breathing measurements between infants who developed postdischarge respiratory disease and those who did not (Table 3). Although there was a trend toward a higher phase angle in infants with BPD who had postdischarge respiratory disease compared with those who did not, this difference was not significant, and all other tidal breathing measurements were similar in both groups (Table E3). We also did not observe any association between tidal breathing measurements and secondary outcomes, such as hospitalization (Table E4). BDR as assessed by a decrease in phase angle after bronchodilator was present in 46% of the study cohort, whereas BDR as assessed by an increase in Tpef/Te was present in 24% (Table 3). A decrease in PA after bronchodilator was more common in infants with postdischarge respiratory disease than those without (50% vs. 38.5%, P = 0.051), although this difference did not meet our prespecified significance level of P ≤ 0.05. There was no significant association between results on the basis of oximetry while sleeping and postdischarge respiratory disease status at 1 year.

Table 3.

Tidal breathing data obtained near the time of discharge in infants with and without postdischarge respiratory disease after discharge

| Tidal Breathing Measurements | No. | No Postdischarge Respiratory Disease* | Postdischarge Respiratory Disease* | Mean/Median Difference or OR (95% CI†) | P Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIP | |||||

| Phase angle, degrees | 433 | 77.5 ± 44.5 | 80.0 ± 45.9 | 2.5 (−6.6 to 11.5) | 0.59 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 433 | 60.2 ± 8.2 | 60.6 ± 9.3 | 0.4 (−1.4 to 2.2) | 0.69 |

| Tpef/Te | 433 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0.84 |

| %RCi | 433 | 0.17 ± 0.28 | 0.16 ± 0.29 | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.04) | 0.67 |

| Sleep oximetry (in room air only) | |||||

| No. of desaturations ≥4%/s | 262 | 0.39 (0.23 to 0.81) | 0.45 (0.20 to 0.85) | 0.06 (−0.03 to 0.18) | 0.75 |

| Longest apnea, s | 66 | 4.2 (3.5 to 5.48) | 4.3 (3.2 to 5.38) | 0.2 (−0.7 to 0.6) | 0.60 |

| Fall in O2 saturation/s, % | 190 | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.05) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.2) | 0.95 |

| Lowest SpO2, % | 257 | 87.0 (81.0 to 91.0) | 88.0 (84.0 to 91.0) | 1.0 (−1.0 to 3.0) | 0.56 |

| Bronchodilator response | |||||

| Phase angle decrease | 1.60 (1.00 to 2.55) | 0.05 | |||

| No | 67 (61.5) | 106 (50.0) | |||

| Yes | 42 (38.5) | 106 (50.0) | |||

| Tpef/Te increase | 1.54 (0.88 to 2.71) | 0.13 | |||

| No | 88 (80.7) | 155 (73.1) | |||

| Yes | 21 (19.3) | 57 (26.9) |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; RCi = contribution of rib cage expansion to inspiratory tidal volume; RIP = respiratory inductance plethysmography; SD = standard deviation; SpO2 = oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry; Tpef/Te = ratio of time to peak expiratory flow over total expiratory time.

Presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) or No. (%).

95% CIs of median differences obtained through bootstrap method (31).

t test with equal variance or Wilcoxon test.

Discussion

In this prospective study of a cohort of extremely low GA neonates who were breathing ambient air or supported by low-flow nasal cannulas, we found different tidal breathing patterns at 37 weeks PMA compared with normal term neonates, but these results were not associated with the diagnosis of BPD or subsequent postdischarge respiratory disease. The frequency of BDR near the time of discharge from the NICU was increased in infants with subsequent postdischarge respiratory disease compared with those without, but not significantly so.

Other investigators have performed tidal breathing measurements in preterm infants around the time of discharge. The Bern Infant Study measured Tpef/Te using a pneumotachometer and assessed lung clearance index and FRC by multiple-breath washout at 44 weeks PMA in a cohort of preterm and full-term infants (33). Tpef/Te was lower in infants with BPD than those without BPD. There was no difference in lung clearance index between the two groups, and FRC was slightly lower in the infants with BPD. Warren and colleagues performed RIP in preterm infants and found that mean PA was 61°, compared with 12° in the full-term comparison group (34). Their results are not directly comparable to ours, because Warren and colleagues studied infants in the prone position and included infants with a GA greater than 29 weeks (34). However, overall the findings in these two studies are in agreement with ours. For example, Warren and colleagues did not observe a significant association between higher PA and BPD diagnosis (34). We enrolled many more infants than either the Bern study or the study by Warren and colleagues, and all were born before 29 weeks PMA. We also prospectively collected postdischarge clinical data that allowed us to analyze associations between tidal breathing measurements and clinical outcomes. Ours was the first study to assess the prognostic significance of BDR in premature infants; among 353 infants receiving albuterol we found no significant association between tidal breathing–based BDR at the time of discharge and subsequent postdischarge respiratory disease.

The Bern Infant Study found that lower Tpef/Te was associated with increased wheezing in the first year of life, but addition of tidal breathing results to clinical variables did not increase the ability of a predictive model to predict future wheezing in preterm infants (35). Bentsen and colleagues also found that a low Tpef/Te in preterm infants was predictive of respiratory morbidity in the first year of life (36). In addition to Tpef/Te, we also studied PA and sleep hypoxemia, but we found that none of these measurements was predictive of future respiratory morbidity in the PROP cohort. It is difficult to compare our study to others because of differences in GA, methods used to measure Tpef/Te (i.e., pneumotachometer versus RIP), and different definitions of postdischarge respiratory disease. Furthermore, Bentsen and colleagues studied a much smaller cohort with a much lower prevalence of first year respiratory morbidity (36). Taken together, our study and others suggest that tidal breathing measurements most likely have limited utility in predicting short-term respiratory outcomes in extremely preterm infants.

Other than physiologically unimportant differences in Tpef/Te, there was little association between tidal breathing measurements and BPD status (33). This may be because our definition of BPD, although conventional (16, 17), is based only on need for supplemental O2. Hjalmarson and colleagues have shown a lack of association between the need for supplemental O2 and measures of respiratory mechanics, such as compliance and conductance (37). It is likely that tidal breathing measurements reflect respiratory mechanics, but in a given infant respiratory mechanics per se may be less responsible for hypoxemia than, for example, dysfunctional responses of the pulmonary circulation leading to ventilation–perfusion mismatching. Furthermore, in some preterm infants, immature control of breathing may contribute more than parenchymal lung disease in causing a need for supplemental O2 (38).

Tidal breathing measurements from the PROP preterm infants were abnormal compared with our term cohort, but there was no difference in these measurements among PROP enrollees who developed postdischarge respiratory disease compared with those who did not. These results suggest that factors other than abnormal respiratory mechanics at discharge may make a greater contribution to the risk of persistent pulmonary disease in these extremely preterm infants. A recent study of pulmonary outcomes associated with chorioamnionitis supports this hypothesis; chorioamnionitis was associated with increased pulmonary morbidity in the first 2 years of life, but it was not associated with lower lung function measured by infant PFTs (39).

BDR in full-term infants is associated with an increased likelihood of wheezing in infancy and childhood (40, 41). BDR as assessed by decline in phase angle after bronchodilator administration was more common in PROP infants with postdischarge respiratory disease than those without, although this difference just failed to meet our prespecified threshold for statistical significance. An increased phase angle can be caused by several mechanisms, including upper airway obstruction and increased lung compliance (42, 43), and there are limited studies using phase angle as a measure of BDR (26). With these caveats in mind, our results suggest the possibility that BDR is a risk factor for postdischarge respiratory morbidity in extremely preterm infants, and further study of this relationship should be conducted.

There are limitations to our inclusion criteria and outcome measurements that may have affected our results. For example, we excluded infants receiving more than 1 L/min of flow. This may have excluded infants with the potential for more severe postdischarge respiratory disease from our study and likely selected for a group with at most moderate respiratory function impairment. This is consistent with the finding of a lower rate of postdischarge respiratory disease among infants in our cohort who were well enough to have RIP performed compared with the entire PROP cohort (18). The inclusion criterion of infants receiving less than or equal to 1 L/min, in particular, may have contributed substantially to the lack of association between prebronchodilator tidal breathing results and BPD or postdischarge respiratory disease. However, even in this group of preterm infants with minimal respiratory support at NICU discharge, there was substantial postdischarge respiratory morbidity, which was the motivation for our conducting a study to identify noninvasive physiologic markers of future respiratory illness. Our definition of postdischarge respiratory disease has not been validated or used in studies outside of PROP. However, it is similar to those use by other studies (3), and the diagnosis of BPD increased the likelihood of having postdischarge respiratory disease (18), consistent with many other studies of preterm respiratory outcomes.

Tidal breathing measurements remain an indirect assessment of respiratory function and are affected by factors other than intrathoracic lung mechanics. For example, thoracoabdominal synchrony is affected by upper airway obstruction as well as lower airway obstruction (42), and we cannot rule out that the increased phase angle we observed was due to upper airway obstruction. In contrast to some other studies, we did not directly measure Tpef/Te with a pneumotachometer; rather, it was derived from changes in the sum of thoracic and abdominal expansion over time, changes in flow whose detection could be delayed when the measurements rely on rib cage or abdominal excursion. Finally, among infants studied at 32 weeks PMA, it has been shown that some infants are able to keep their SpO2% greater than 90% in room air, despite having marked asynchrony, with PA much greater than 80° in many cases (44).

In summary, we have shown that extremely low GA neonates breathing ambient air or on low-flow nasal cannula support have abnormal tidal breathing patterns, but these patterns do not differ between infants with and without BPD. Prebronchodilator and post-bronchodilator tidal breathing results were not predictive of postdischarge respiratory disease. Our results suggest that factors other than altered respiratory mechanics alone, such as response to respiratory viral infections among infants whose mechanics are already more or less compromised, may contribute more to future respiratory problems in the preterm population (45).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants U01 HL101794, U01 HL101456, U01 HL101798, U01 HL101813, U01 HL101465, U01 HL 101800, and 5RO1 HL105702.

Author Contributions: C.L.R., R.F., and J.S.K. led the project. C.L.R., S.D.D., E.E., A.J., P.E.M., H.B.P., J.K.S., and J.S.K. contributed to the design of the study and to data collection. J.K. and C.C. performed tidal breathing data analysis. C.L.R., R.F., S.D.D., E.E., A.J., P.E.M., H.B.P., J.K.S., and J.S.K. analyzed and interpreted the data. C.L.R., R.F., and J.S.K. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on behalf of the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program

References

- 1.Baraldi E, Filippone M. Chronic lung disease after premature birth. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1946–1955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra067279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhandari A, Panitch HB. Pulmonary outcomes in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30:219–226. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens TP, Finer NN, Carlo WA, Szilagyi PG, Phelps DL, Walsh MC. Respiratory outcomes of the surfactant positive pressure and oximetry randomized trial (SUPPORT) J Pediatr. 2014;165:240–249, e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisgaard H, Jensen SM, Bønnelykke K. Interaction between asthma and lung function growth in early life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1183–1189. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1922OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Håland G, Carlsen KCL, Sandvik L, Devulapalli CS, Munthe-Kaas MC, Pettersen M. Reduced lung function at birth and the risk of asthma at 10 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1682–1689. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez FD, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Taussig LM. Diminished lung function as a predisposing factor for wheezing respiratory illness in infants. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1112–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810273191702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life: the Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:133–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner SW, Palmer LJ, Rye PJ, Gibson NA, Judge PK, Young S, et al. Infants with flow limitation at 4 weeks: outcome at 6 and 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1294–1298. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200110-018OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baraldi E, Filippone M, Trevisanuto D, Zanardo V, Zacchello F. Pulmonary function until two years of life in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:149–155. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tepper RS, Morgan WJ, Cota K, Taussig LM. Expiratory flow limitation in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 1986;109:1040–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kao LC, Warburton D, Cheng MH, Cedeño C, Platzker AC, Keens TG. Effect of oral diuretics on pulmonary mechanics in infants with chronic bronchopulmonary dysplasia: results of a double-blind crossover sequential trial. Pediatrics. 1984;74:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerhardt T, Hehre D, Feller R, Reifenberg L, Bancalari E. Serial determination of pulmonary function in infants with chronic lung disease. J Pediatr. 1987;110:448–456. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feher A, Castile R, Kisling J, Angelicchio C, Filbrun D, Flucke R, et al. Flow limitation in normal infants: a new method for forced expiratory maneuvers from raised lung volumes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1996;80:2019–2025. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.6.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer J, Allen J, Mayer O. Tidal breathing analysis. Neoreviews. 2004;5:e186–e193. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pryhuber GS, Maitre NL, Ballard RA, Cifelli D, Davis SD, Ellenberg JH, et al. Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program Investigators. Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program (PROP): study protocol of a prospective multicenter study of respiratory outcomes of preterm infants in the United States. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:37. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0346-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poindexter BB, Feng R, Schmidt B, Aschner JL, Ballard RA, Hamvas A, et al. Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program. Comparisons and limitations of current definitions of bronchopulmonary dysplasia for the prematurity and respiratory outcomes program. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1822–1830. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201504-218OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shennan AT, Dunn MS, Ohlsson A, Lennox K, Hoskins EM. Abnormal pulmonary outcomes in premature infants: prediction from oxygen requirement in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 1988;82:527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller RL, Feng R, DeMauro SB, Ferkol T, Hardie W, Rogers EE, et al. Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and perinatal characteristics predict 1-year respiratory outcomes in newborns born at extremely low gestational age: a prospective cohort study. J Pediatr. 2017;187:89–97, e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maitre NL, Ballard RA, Ellenberg JH, Davis SD, Greenberg JM, Hamvas A, et al. Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program. Respiratory consequences of prematurity: evolution of a diagnosis and development of a comprehensive approach. J Perinatol. 2015;35:313–321. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prechtl HF. The behavioural states of the newborn infant (a review) Brain Res. 1974;76:185–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer OH, Clayton RG, Sr, Jawad AF, McDonough JM, Allen JL. Respiratory inductance plethysmography in healthy 3- to 5-year-old children. Chest. 2003;124:1812–1819. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren CL, Rosenfeld M, Mayer OH, Davis SD, Kloster M, Castile RG, et al. Analysis of the associations between lung function and clinical features in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47:574–581. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stocks J, Dezateux CA, Jackson EA, Hoo AF, Costeloe KL, Wade AM. Analysis of tidal breathing parameters in infancy: how variable is TPTEF:TE? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1347–1354. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulm LN, Hamvas A, Ferkol TW, Rodriguez OM, Cleveland CM, Linneman LA. Sources of methodological variability in phase angles from respiratory inductance plethysmography in preterm infants. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2014;11:753–760. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-363OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams JA, Zabaleta IA, Stroh D, Johnson P, Sackner MA. Tidal volume measurements in newborns using respiratory inductive plethysmography. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:585–588. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen JL, Wolfson MR, McDowell K, Shaffer TH. Thoracoabdominal asynchrony in infants with airflow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:337–342. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris MJ, Lane DJ. Tidal expiratory flow patterns in airflow obstruction. Thorax. 1981;36:135–142. doi: 10.1136/thx.36.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Ent CK, Brackel HJ, van der Laag J, Bogaard JM. Tidal breathing analysis as a measure of airway obstruction in children three years of age and older. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1253–1258. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.4.8616550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hershenson MB, Stark AR, Mead J. Action of the inspiratory muscles of the rib cage during breathing in newborns. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:1207–1212. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.5.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tourneux P, Leke A, Kongolo G, Cardot V, Degrugilliers L, Chardon K. Relationship between functional residual capacity and oxygen desaturation during short central apneic events during sleep in “late preterm” infants. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:171–176. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318179951d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh M, Parr WC, Singh K, Babu GJ. A note on bootstrapping the sample median. Ann Stat. 1984;12:1130–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen JE, Sun XG, Adame D, Wasserman K. Argument for changing criteria for bronchodilator responsiveness. Respir Med. 2008;102:1777–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Latzin P, Roth S, Thamrin C, Hutten GJ, Pramana I, Kuehni CE. Lung volume, breathing pattern and ventilation inhomogeneity in preterm and term infants. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren RH, Horan SM, Robertson PK. Chest wall motion in preterm infants using respiratory inductive plethysmography. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2295–2300. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10102295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Proietti E, Riedel T, Fuchs O, Pramana I, Singer F, Schmidt A, et al. Can infant lung function predict respiratory morbidity during the first year of life in preterm infants? Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1642–1651. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00149213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bentsen MH, Markestad T, Øymar K, Halvorsen T. Lung function at term in extremely preterm-born infants: a regional prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016868. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hjalmarson O, Brynjarsson H, Nilsson S, Sandberg KL. Persisting hypoxaemia is an insufficient measure of adverse lung function in very immature infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F257–F262. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coste F, Ferkol T, Hamvas A, Cleveland C, Linneman L, Hoffman J, et al. Ventilatory control and supplemental oxygen in premature infants with apparent chronic lung disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F233–F237. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDowell KM, Jobe AH, Fenchel M, Hardie WD, Gisslen T, Young LR, et al. Pulmonary morbidity in infancy after exposure to chorioamnionitis in late preterm infants. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:867–876. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201507-411OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner SW, Palmer LJ, Rye PJ, Gibson NA, Judge PK, Cox M, et al. The relationship between infant airway function, childhood airway responsiveness, and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:921–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200307-891OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao W, Barbé-Tuana FM, Llapur CJ, Jones MH, Tiller C, Kimmel R, et al. Evaluation of airway reactivity and immune characteristics as risk factors for wheezing early in life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:483–488, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sivan Y, Deakers TW, Newth CJ. Thoracoabdominal asynchrony in acute upper airway obstruction in small children. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:540–544. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen JL, Greenspan JS, Deoras KS, Keklikian E, Wolfson MR, Shaffer TH. Interaction between chest wall motion and lung mechanics in normal infants and infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1991;11:37–43. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brennan C, Ulm L, Julian S, Hamvas A, Ferkol T, Hoffman J, et al. Thoracoabdominal asynchrony is not associated with oxyhemoglobin saturation in recovering premature infants. Neonatology. 2017;111:297–302. doi: 10.1159/000452787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pryhuber GS. Postnatal infections and immunology affecting chronic lung disease of prematurity. Clin Perinatol. 2015;42:697–718. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.