To the Editor:

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that most often affects the lungs and is characterized by noncaseating granulomas. Pathogenesis is believed to result from an abnormal cell-mediated immune response to an unknown stimulant or antigen, typically in genetically susceptible individuals (1). The highest incidence has been observed among African Americans (2); however, the national burden of sarcoidosis in the United States has not been well described, including the regional variation among white and black racial groups. In this study, we analyzed sarcoidosis-associated (SA) hospitalizations to obtain regional race- and sex-specific estimates and, specifically, to examine the black–white disparity within regions for both men and women. Although the racial disparity in sarcoidosis incidence has been well described (2–4), the consistency of this differential across regions among both men and women has not been examined. Preliminary results from this study were presented at the American Thoracic Society conference, May 13 to 18, 2016 in San Francisco, California.

Methods

Study population

We extracted discharge (billing) data with SA hospitalizations for the period 2002 to 2012 from the State Inpatient Databases maintained by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality through the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (5). The State Inpatient Databases include 97% of all community hospital inpatient discharges, with 48 states currently participating (5). Of these states, 18 provided continuous reporting of race level throughout the study period and had at least 10 SA claims within black/white strata; these states represented 60% of the total U.S. population in 2012 (6). We extracted claims where the International Classification of Diseases, ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code for sarcoidosis (135.0) was listed as the discharge code in the primary or secondary diagnostic fields. Because of small cell sizes (<10 SA hospitalizations), SA hospitalizations among persons aged younger than 20 years and where race was not listed as black or white were excluded. States were grouped into the following census regions for analysis: Midwest (MI, IA, KS, MO, WI), Northeast (NY, NJ, CT, MA), South (SC, GA, FL, MD, TN, TX), and West (AZ, CA, CO).

Data analysis

U.S. census data were used to estimate the regional populations by age group, sex, and race/ethnicity during the study period. Regional rates were age adjusted using the 2010 U.S. census population as the standard, excluding the population aged younger than 20 years.

Results

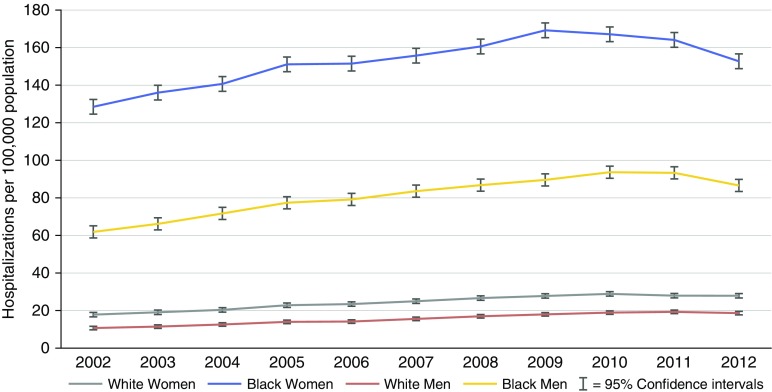

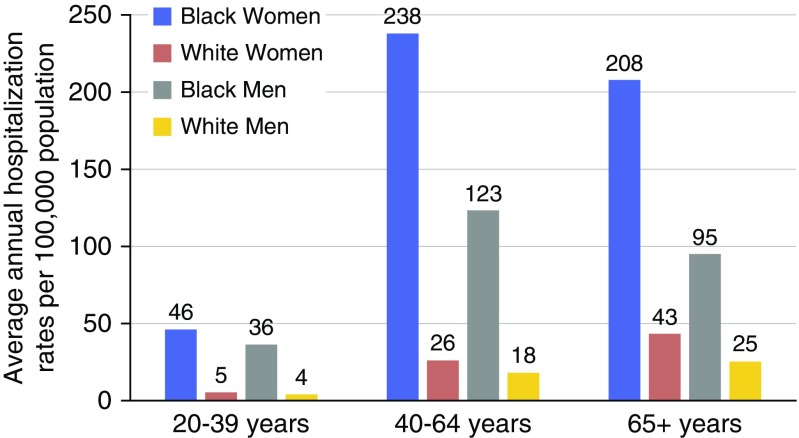

From 2002 through 2012, 376,947 SA hospitalizations were identified, including 200,438 (53%) among blacks and 176,509 (47%) among whites. The annual hospitalization rate remained relatively stable across all groups (Figure 1). Among both black men and women, the peak hospitalization rate occurred among those aged 40 to 64 years, with a rate of 238/100,000 (95% confidence interval [CI], 233–243) for black women and 123/100,000 (95% CI, 119–127) among black men. In contrast, for whites, the highest rates were among those aged 65 years or older: 43/100,000 (95% CI, 42–45) among women and 25/100,000 (95% CI, 24–26) among men (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Sarcoidosis-associated hospitalizations by race, sex, and year, 2002 to 2012.

Figure 2.

Average annual sarcoidosis-associated hospitalizations by age, race, and sex, 2002 to 2012.

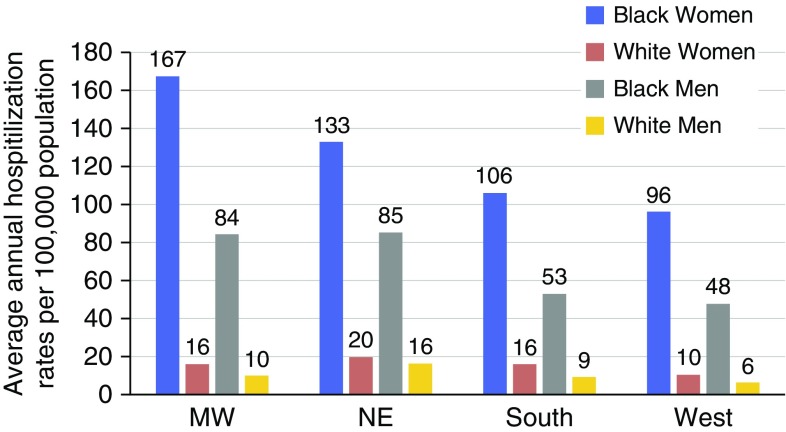

After stratifying by region and racial group, the highest average annual age-adjusted hospitalization rate was observed among black women in the Midwest (167/100,000; 95% CI, 166–169) and Northeast (133/100,000; 95% CI, 132–133). Among black men, rates were also highest in the Midwest (8/100,000; 95% CI, 84–85) and Northeast (85/100,000; 95% CI, 84–86), with rates nearly identical to each other in those two regions. Across all regions, black women had a seven- to ninefold increased risk of SA hospitalizations compared with white women, and black men had a five- to eightfold increased risk compared with white men (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Average annual age-adjusted sarcoidosis-associated hospitalizations by race/ethnicity and region. MW = Midwest; NE = Northeast.

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative sample of SA hospitalizations, we found a consistent and marked racial disparity in SA hospitalizations across all four regions of the United States. The black–white racial disparity was of similar magnitude across regions. Although prior studies have described rates separately by racial group and region in a national sample of women (4) and by race and region separately (3), these studies did not present rates by racial groups within regions. Environmental risk factors in the home and workplace have been identified, including agriculture exposures and microbial bioaerosols (7); although race may serve as a proxy for differences in home or occupational environmental exposures, the similar magnitude of racial differences in sarcoidosis risk across regions suggests that the contributors to this difference are likely consistent across regions and include genetic ancestry. Environmental and occupational differences vary widely across the regions of the United States. Twin studies and genome-wide association studies have highlighted the role of genetic susceptibility in the risk of disease, including candidate genes specific to African Americans (8). A limitation of this study is that we could not assess the degree to which racial disparities in hospitalizations were related to differences in severity of disease by race.

Differences in sarcoidosis rates by geographic region remain poorly understood. A study conducted among World War II servicemen found the highest rates among African Americans in the Southeastern United States, with the highest risk among residents in areas with specific soil types and rural areas with low population density (9). A recent large, national multicenter case–control study identified several environmental risks, including occupational exposures to insecticides and work areas with musty odors (7). A single-site study found a significant risk of certain “rurally linked” environmental exposures, including wood-burning stoves and seasonal use of indoor fireplaces (10). Sarcoidosis has multiple etiologies, including mycobacteria and other microbes as well as other environmental triggers (7, 8). Occupational and urbanization patterns have changed substantially in the United States since the turn of the century, with a 96% decline in farming and a 64% decline in manual laborers (11). Regional and race-specific disease patterns have likely shifted as a result of changing occupational exposures and other urbanization patterns. In summary, we demonstrate racial disparities for both men and women across regions of the United States, highlighting the importance of both host and environmental factors to disease etiology. Although the black–white disparity in sarcoidosis incidence and prevalence has been well described, the consistency of this disparity across the widely disparate regions of the United States has not.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the contributing hospitals and state data organizers who contributed to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project during the period of 2002 to 2012.

Footnotes

Supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391–399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Jr, Maliarik MJ, Iannuzzi MC. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:234–241. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, Crystal RG, Culver DA, Drent M, et al. Sarcoidosis in America: analysis based on health care use. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1244–1252. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-760OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumas O, Abramovitz L, Wiley AS, Cozier YC, Camargo CA., Jr Epidemiology of sarcoidosis in a prospective cohort study of U.S. women. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:67–71. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-568BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HCUP State Inpatient Databases (SID). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2002–2012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [accessed 2018 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Census BureauSection 1. Population. 2012 [accessed year month day]. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2011/compendia/statab/131ed/tables/pop.pdf

- 7.Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, Rossman MD, Barnard J, Frederick M, et al. ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324–1330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-249OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moller DR, Rybicki BA, Hamzeh NY, Montgomery CG, Chen ES, Drake W, et al. Genetic, immunologic, and environmental basis of sarcoidosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:S429–S436. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201707-565OT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gentry JT, Nitowsky HM, Michael M., Jr Studies on the epidemiology of sarcoidosis in the United States: the relationship to soil areas and to urban-rural residence. J Clin Invest. 1955;34:1839–1856. doi: 10.1172/JCI103240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kajdasz DK, Lackland DT, Mohr LC, Judson MA. A current assessment of rurally linked exposures as potential risk factors for sarcoidosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyatt ID. Occupational changes during the 20th century. Mon Labor Rev. 2006;129:35. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.