Abstract

Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare vasoformative malignant neoplasm that can present a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We describe a 76-year-old Caucasian man with right upper eyelid swelling and nodularity, initially suspected clinically to represent either ocular adnexal lymphoma or basal cell carcinoma. Incisional biopsy and wide resection of the mass with frozen section control of margins were interpreted as compatible with hobnail (Dabska-retiform) hemangioendothelioma. Foci of atypia were noted in the tumor, raising speculation of evolution into a more aggressive neoplasm, such as conventional angiosarcoma. The patient subsequently underwent two additional wide resections with frozen section control of margins in an attempt to obtain complete excision of residual tumor, which demonstrated histopathologic features favoring angiosarcoma. The histologic material from the original and subsequent resections was sent in consultation to several soft tissue pathology experts and the final diagnosis of low-grade cutaneous angiosarcoma was established. Despite repeated surgical interventions, there was continued persistence of the tumor in the deep orbital tissues. Various management options, including adjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy with and without orbital exenteration, were discussed. The patient decided against further surgical intervention and is currently undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy. This case illustrates the diagnostic and management difficulties of ocular adnexal angiosarcoma.

Keywords: Eye, Eyelid, Tumor, Angiosarcoma, Hemangioendothelioma, Hobnail hemangioendothelioma, Retiform hemangioendothelioma

Established Facts

Angiosarcoma can rarely involve the eyelid skin and soft tissue.

Management of ocular adnexal angiosarcoma can be challenging due to its proximity to the globe.

Novel Insights

• Well-differentiated angiosarcoma can mimic hobnail (Dabska-retiform) hemangioendothelioma.

This case illustrates the challenges of frozen section diagnosis of low-grade angiosarcoma.

Introduction

Angiosarcoma is a malignant tumor that recapitulates the functional and morphologic features of normal vascular and lymphatic endothelium. Angiosarcoma represents one of the rarest soft tissue neoplasms, comprising less than 1% of all sarcomas [1]. Although cutaneous angiosarcoma has a predilection for the head and neck region, primary eyelid involvement is rare, with less than 30 cases reported in the literature [2, 3, 4, 5].

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a notorious clinical masquerader, mimicking benign vascular tumors, inflammatory lesions, edema, and infection [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. The rarity of ocular adnexal angiosarcoma further contributes to the clinical diagnostic challenge, with about one quarter of the lesions initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma or pyogenic granuloma [4]. Similarly, histopathologic diagnosis of angiosarcoma can be problematic due to the potential overlap between reactive, benign, and intermediate malignant vascular lesions [1]. Additionally, proximity of eyelid angiosarcoma to the globe complicates its management [9]. Herein, we describe a 76-year-old man with a primary eyelid angiosarcoma. The unusual histopathologic features of the tumor, which resulted in diagnostic controversy, and the surgical management challenges are discussed.

Case Report

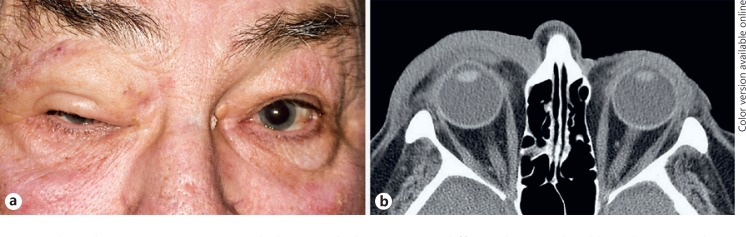

A 76-year-old Caucasian man with a remote past medical history of prostate adenocarcinoma, successfully managed with radiotherapy/chemotherapy, presented to his local ophthalmologist with right upper eyelid edema, blepharoptosis, and palpable eyelid nodularity of 5 months' duration (Fig. 1a). Computed tomography of the orbit demonstrated right preseptal and periorbital soft tissue swelling without a distinct mass or fluid (Fig. 1b). Metastatic workup was negative. Incisional biopsy, performed for suspected basal cell carcinoma versus ocular adnexal lymphoma, was interpreted as an atypical vascular neoplasm, most compatible with hemangioendothelioma. The patient was referred for further management and underwent wide resection of the mass with frozen section control of margins, cryotherapy, and paramedian forehead flap reconstruction.

Fig. 1.

Clinical presentation. a External photograph demonstrates diffuse edema and mild erythema involving the right upper eyelid and superior orbit, associated with eyelid ptosis. b Axial post-contrast computed tomography scan shows a diffuse, poorly circumscribed preseptal and periorbital swelling, without a distinct mass lesion.

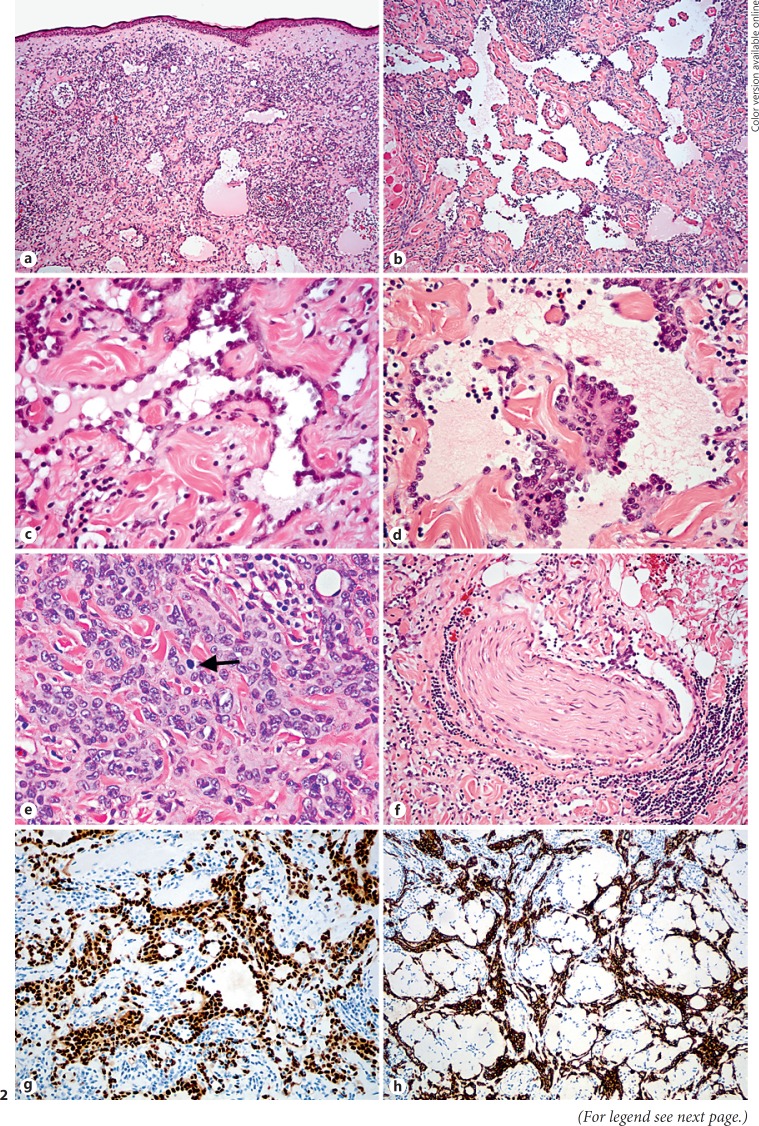

Microscopic evaluation demonstrated a well-differentiated neoplasm, with vascular channel formation, lined by cells with predominantly small nuclei extending into the lumen of the channels in a “hobnail” configuration, and forming intraluminal papillae with focal hyaline cores (Dabska-like morphology) (Fig. 2). Rare foci of cells with larger nuclei, occasional nucleoli, and sheet-like configuration were noted and considered atypical, but still falling within the spectrum of the potential hemangioendothelioma. The mitotic rate varied from 0 in 10 high-power fields in the areas of typical hemangioendothelioma to 4 in 10 high-power fields in the more atypical foci (Fig. 2). The vascular channels were associated with hyaline sclerosis and intense lymphocytic infiltrate. Immunohistochemical stains showed that the tumor cells co-expressed vascular and lymphatic endothelial markers CD31, CD34, ERG, and D2–40 (Fig. 2). HHV-8 immunostain was negative. The Ki-67 proliferative index varied from 1% in most of the lesion to 15–20% in the atypical areas. In consultation with a soft tissue pathologist, these features were consistent with hobnail (retiform) hemangioendothelioma with foci of atypical features. Presence of the atypical foci raised a concern for evolution into a more aggressive neoplasm.

Fig. 2.

Pathologic findings, initial excision. a Infiltrative neoplasm, composed of well-formed channels with features of vascular and lymphatic endothelium, involves the eyelid dermis. b The elongated channels have branching and anastomosing arrangement, reminiscent of rete testis, and are surrounded by hyalinized collagen and prominent inflammatory infiltrate. c The channels are lined by the uniform ovoid cells that protrude into the lumen in a hobnail fashion. d Large papillary tufts with central hyalinized cores extend into the lumen of the channel, which contains few lymphocytes and material reminiscent of lymph. e Cellular aggregates of cells with slightly larger and more pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and mitotic activity (arrow) permeate the collagen bundles. f Perineural invasion is identified. g The neoplastic cells immunoreact with vascular and lymphatic endothelial marker ERG. h There is diffuse immunoreactivity of the tumor for lymphatic endothelial marker D2–40. Stains: H&E (a-f), ERG (g), and D2–40 (h); original magnification ×10 (a), ×20 (b, h), ×50 (f, g), ×100 (c–e).

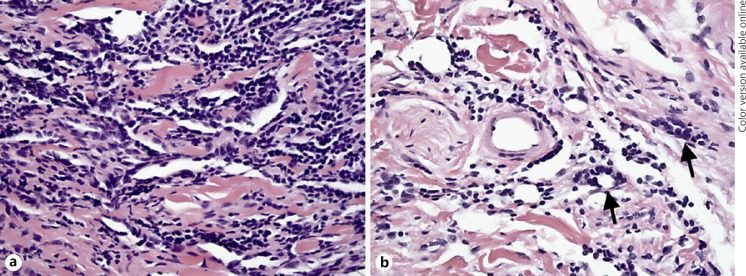

Despite an attempt to achieve complete resection, the neoplasm involved deep soft tissue and periosteal margins. The patient subsequently underwent two additional wide resections with frozen section control of margins aiming at complete excision of tumor. The residual neoplasm demonstrated a permeative histology with dissection of collagen planes, orbital fat and muscle infiltration, and more prominent sheet-like aggregates (Fig. 3a). These findings were interpreted as compatible with low-grade angiosarcoma. Due to prognostic and management implications, the attempts were made to obtain a unifying pathologic diagnosis. The histologic material from the original and subsequent resections was sent in consultation to several soft tissue experts (C.F., M.M.M., and K.C., see acknowledgements). Although there was some difference of opinion, the final diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma in all resected tissues was favored based on the permeative nature of the lesion and degree of cellular multilayering in a clinical context of rapidly evolving lesion on the facial skin of an elderly Caucasian patient.

Fig. 3.

Pathologic findings, re-excision. a Prominent multilayering of hyperchromatic cells, which dissect collagen bundles without forming well-defined vascular channels, is present. b Frozen section margin demonstrates inconspicuous foci of malignant cells (arrows), morphologically similar to the adjacent lymphocytic infiltrate. Stain: H&E; original magnification ×100.

All surgical procedures were complicated by the presence of angiosarcoma at the surgical margins. Despite the apparent clearance of surgical margins on intraoperative frozen sections, permanent sections revealed angiosarcoma at tissue margins (Fig. 3b). Various management options, including adjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy with and without orbital exenteration, were discussed. The patient decided against further surgical intervention and is currently undergoing palliative therapy with adjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy.

Discussion

Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare vasoformative malignant neoplasm with predilection for the head and neck region of Caucasians around the 7th decade of life [1]. This malignancy frequently involves the scalp and forehead and can secondarily extend to involve periocular tissues [8, 10]. Tumors localized to the eyelid (primary eyelid angiosarcoma) occur in demographically similar patient populations but are exceedingly rare, with less than 30 patients described in the literature [2, 3, 4, 5, 8]. Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a great clinical masquerader, mimicking a variety of benign and malignant tumors and reactive processes. This neoplasm most frequently presents as a rapidly evolving erythematous to violaceous mass or plaque, which can be mistaken for edema, inflammation, or hematoma [2, 3, 4, 5]. Other manifestations include solitary blue-to-violaceous nodule suggestive of lymphoma, keratotic flesh-toned papule mimicking squamous or basal cell carcinoma, and multicentric nodules reminiscent of metastases [2]. The malignancy in our patient was similarly interpreted as being clinically compatible with either basal cell carcinoma or lymphoma or atypical preseptal edema, highlighting the diagnostic challenge.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is notoriously difficult to diagnose histopathologically. The classic description is that of a moderately differentiated lesion with moderate nuclear atypia that forms distinct vascular channels of irregular size and shape with occasional luminal endothelial tufts, focally communicating to form an anastomosing network of sinusoids and dissecting through the dermal collagen. However, cutaneous angiosarcoma can have high-grade morphology and solid sheet-like epithelioid areas mimicking carcinoma and high-grade fibrosarcoma [1]. The well-differentiated, low-grade cutaneous angiosarcoma frequently mimics benign hemangiomas and reactive vascular lesions, including papillary endothelial hyperplasia and exuberant granulation tissue (pyogenic granuloma) [1, 2, 11]. The distinction of cutaneous angiosarcoma from vascular tumors of intermediate malignancy, such as hemangioendothelioma, is particularly challenging.

Hobnail (Dabska-retiform) hemangioendothelioma, a neoplasm of intermediate malignancy and regarded as a variant of a low-grade angiosarcoma, has been classically described on the distal extremities of middle-aged adults. However, this tumor can occur in older age distribution and in other locations, including the head and neck region [1, 12]. This tumor is characterized by a poorly circumscribed proliferation of long, well-formed, retiform vascular channels reminiscent of rete testis in the dermis and subcutis, lined by the protuberant (hobnail-like) endothelial cells with intraluminal papillary tufts and occasional hyaline collagenous cores. The vascular channels are surrounded by hyaline sclerosis and lymphocytes. Most cases of hobnail hemangioendothelioma show focally solid areas composed of monomorphic spindle or epithelioid cells and frequently form sinusoids, analogous to angiosarcoma. However, dissection of the collagen planes by small groups of endothelial cells and pronounced endothelial multilayering, found in conventional angiosarcoma, does not occur with hemangioendothelioma [1, 11]. Similar to cutaneous angiosarcoma, hobnail hemangioendothelioma demonstrates immunoreactivity for markers of both vascular and lymphatic endothelial differentiation. Thus, immunoreactivity for D2–40, noted to be helpful in distinguishing cutaneous angiosarcoma from other vascular lesions, is not useful when applied in this context to hobnail hemangioendothelioma [1, 8]. Cutaneous angiosarcoma has been shown to have a Ki-67 proliferative index of >10%, which may aid in its distinction from benign and reactive vascular proliferations [8]. The utility of Ki-67 in distinguishing angiosarcoma from the vascular tumors of intermediate malignancy, such as hemangioendothelioma, is not well established [1, 11]. The marked morphologic and immunohistochemical overlap between the hobnail hemangioendothelioma and well-differentiated, low-grade cutaneous angiosarcoma led to the diagnostic difficulty in this current case. Availability of additional resection material, which demonstrated more apparent infiltrative morphology and endothelial multilayering, prompted re-review of the original excision, which resulted in revision of the diagnosis from hemangioendothelioma to angiosarcoma. While the unifying diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma on all resection specimens is favored, we cannot exclude the possibility of evolution of preexisting hemangioendothelioma into a more aggressive neoplasm, i.e., conventional cutaneous angiosarcoma.

The distinction between hobnail hemangioendothelioma and cutaneous angiosarcoma has important management and prognostic implications. Hobnail hemangioendothelioma is a neoplasm of intermediate malignancy, with propensity for regional recurrence, but very low metastatic potential [1, 12]. Thus, these lesions are typically managed with a wide local excision, which is the current standard of care, with or without adjuvant radiotherapy [12]. In contrast, cutaneous angiosarcoma demonstrates high propensity for metastases, frequently requiring adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy [2, 4, 9, 13]. Although complete surgical excision of the tumor is the desired goal, cutaneous angiosarcoma frequently invades tissue in a multifocal pattern [1, 2]. This growth pattern, in conjunction with an inherent challenge of diagnosing small foci of well-differentiated vascular tumor on frozen sections, accounts for the frequent positivity of permanent section margins in cutaneous angiosarcoma resections, as exemplified by the surgical course in our patient [14]. Recognition of cutaneous angiosarcoma multifocality and the challenges of complete surgical resection have led to the recent trend of managing this neoplasm with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and biologic agents [9, 13, 15, 16].

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is notoriously recalcitrant to the currently available therapeutic modalities, with frequent metastases to lung, liver, and lymph nodes, and overall 5-year survival between 30–50% [1]. Patients with angiosarcoma involving the eyelids and adjacent facial structures have been recorded to have a 3-year survival of 57% [8]. Tumors strictly isolated to the eyelid have been documented with better prognosis, with no tumor-related mortality 3 years after diagnosis [8]. This favorable clinical course may be related to smaller tumor size and isolated nodular growth pattern [8]. Well-differentiated morphology has been traditionally thought to contribute to the better outcomes of eyelid angiosarcoma [8]. However, the current body of evidence suggests that angiosarcoma grading is not prognostic for cutaneous angiosarcoma [17].

In summary, cutaneous angiosarcoma of the eyelid is a rare and frequently misdiagnosed malignant tumor with a high propensity for local recurrence and metastases. Ophthalmologists and pathologists should be aware of this deadly masquerader and the potential diagnostic and management pitfalls.

Statement of Ethics

The Institution Ethics Review Committee approval was waved for this retrospective case report study. The study was performed in compliance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors have relevant financial relationships with commercial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Christopher Fletcher, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, Dr. Markku Martti Miettinen, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, and Dr. Kumarasen Cooper, MBChB, DPhil, FRCPath, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, for their expert pathology consultation.

References

- 1.Goldblum JR, Folpe AL, Weiss SW, Malignant vascular tumors . Enzinger and Weiss' Soft Tissue Tumors. In: Goldblum JR, Folpe AL, Weiss SW, editors. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2014. pp. pp 703–723. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demirci H, Christanson MD. Eyelid angiosarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013;20:259–262. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.114806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamill EB, Agrawal M, Diwan AH, Winthrop KL, Marx DP. Angiosarcoma of the eyelid with superimposed enterobacter infection. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32:e59–e60. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemanski N, Farber M, Carruth BP, Wladis EJ. Primary adnexal angiosarcoma masquerading as periorbital hematoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59:655–659. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox CA, Wein RO, Ghafouri R, Laver NM, Heher KL, Kapadia MK. Angiosarcoma presenting with minor erythema and swelling. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013;4:59–63. doi: 10.1159/000346952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pontes AB, Ucelli JLR, Obadia DL, Nascimento LVD. Exuberant angiosarcoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:287–289. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, Roy S. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45–47. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.110099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papalas JA, Manavi CK, Woodward JA, Sangueza OP, Cummings TJ. Angiosarcoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathologic comparison between isolated unilateral tumors and tumors demonstrating extrapalpebral involvement. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:694–699. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cf7813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMartelaere SL, Roberts D, Burgess MA, Morrison WH, Pisters PW, Sturgis EM, Ho V, Esmaeli B. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy-specific and overall treatment outcomes in patients with cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face with periorbital involvement. Head Neck. 2008;30:639–646. doi: 10.1002/hed.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gündüz K, Shields JA, Shields CL, Eagle RC, Jr, Nathan F. Cutaneous angiosarcoma with eyelid involvement. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;6:870–871. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calonje JE, Fletcher CDM, Vascular tumors . Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors. In: Fletcher CDM, editor. 4th ed. vol 1. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2013. pp. pp 42–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Faky YH, Al-Mosallam AR, Al-Rikabi AC, Al-Sohaibani MO. Medial canthus retiform hemangioendothelioma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014:491–493. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.126995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito T, Uchi H, Nakahara T, Tsuji G, Oda Y, Hagihara A, Furue M. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and face: a single-center analysis of treatment outcomes in 43 patients in Japan. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1387–1394. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barttelbort SW, Stahl R, Ariyan S. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:55–59. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198907000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Keizer RJ, de Wolff-Rouendaal D, Nooy MA. Angiosarcoma of the eyelid and periorbital region. Experience in Leiden with iridium192 brachytherapy and low-dose doxorubicin chemotherapy. Orbit. 2008;27:5–12. doi: 10.1080/01676830601168926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miura H, Asada Y. Treatment of eyelid lesion of angiosarcoma with facial artery recombinant interleukin-2 (rIL-2) injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:907–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, Ivan D, Aung PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917–925. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2017-204601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]