Abstract

The association between psychiatric and dermatologic disorders has been well characterized in the present literature with estimates of up to 40% of dermatology patients having concomitant psychiatric problems that are often related to their skin condition. Here, we present our experience regarding the implementation of a psychodermatology clinic in Detroit, Michigan. The most commonly referred conditions were delusions of parasitosis, neurotic excoriations, and isotretinoin initiation for patients with a history of psychiatric conditions. Seventy-three percent of referred patients were female. By creating a monthly clinic for patients who are diagnosed with skin conditions and associated psychiatric disorders or psychological symptoms, we are able to meet the needs of these patients with a synergistic relationship between health care providers.

Introduction

The comorbidity between psychiatric and dermatologic disorders has been well characterized in the literature (França et al., 2017, Jafferany and Franca, 2016). Thirty to forty percent of patients with a dermatologic condition have a related comorbid psychiatric presentation (Yadav et al., 2013) but many dermatologists lack specific training to address this comorbidity (Marshall et al., 2016). Only 42% of dermatologists surveyed felt very comfortable treating psychocutaneous disorders (Jafferany et al., 2010). Eighty-five percent of patients with skin conditions reported that psychologic aspects of their skin condition played a significant role in their illness (Marshall et al., 2016).

Women are disproportionately affected by certain psychocutaneous disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder and trichotillomania (Brown, Malakouti, Sorenson, Gupta and Koo, 2015, Duke, Keeley, Geffken and Storch, 2010). Given the prevalence of depression and anxiety in women and the complex interplay between these conditions and skin disorders, female patients stand to benefit from initiatives that address psychocutaneous disorders. A combined psychodermatology clinic presents one such opportunity to meet the needs of these patients. Our aim is to present the results from a novel psychodermatology teaching clinic at a major health system in Detroit, Michigan.

Methods

Patients with comorbid dermatologic and psychiatric disorders are often reluctant to seek behavioral health care. Hence, a monthly, half-day, combined clinic was established at a primary dermatology clinic site in Detroit, Michigan. Clinic staff was educated about baseline depression and anxiety screening, medication consents, and processes related to psychiatric hospitalization.

A retrospective chart review was performed of patients who were referred to the combined clinic between April 2016 and July 2017. Primarily, patients were referred after presenting to a general dermatology clinic. New and returning patients were scheduled for 1-hour and 30-minute appointments, respectively. Clinics were staffed by a psychiatry and dermatology attending as well as residents in both specialties. Subsequently, patients were scheduled for follow up with one or both specialties.

Results

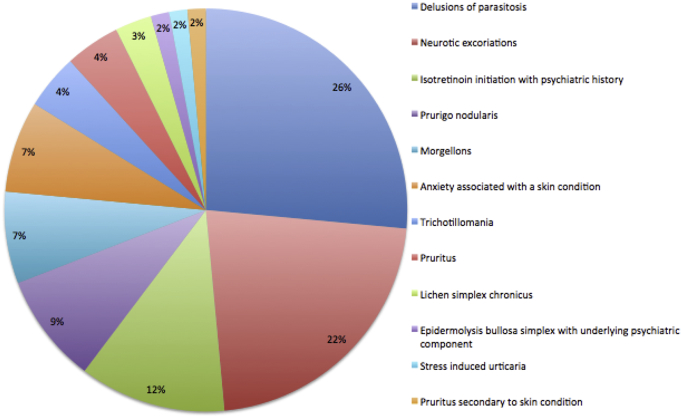

We analyzed data from 16 months of the combined clinic with 68 internal and two external referrals. The top three most commonly referred diagnoses were delusions of parasitosis (n = 18; 26%), neurotic excoriations (n = 15; 22%), and isotretinoin initiation in a patient with a history of psychiatric disorders (n = 8; 12%). Fig. 1 displays all referral diagnoses.

Fig. 1.

Referral diagnosis.

During this time frame, 56 visits were scheduled with 24 patients seen in clinic. The top three diagnoses seen were anxiety associated with a cutaneous condition (n = 8; 33%), delusions of parasitosis (n = 7; 29%), and neurotic excoriations associated with a cutaneous or psychiatric condition (n = 3; 13%). Referral diagnoses were expanded or changed 46% of the time (n = 11; Table 1). Diagnoses were agreed upon after a lengthy discussion of symptoms and criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders within the interdisciplinary team.

Table 1.

Referral diagnoses with subsequent changes or expansions

| Referral diagnosis | Diagnosis next visit |

|---|---|

| Lichen simplex chronicus with depression | Lichen simplex chronicus with adjustment disorder with anxiety |

| Delusions of parasitosis | Folliculitis with neurotic excoriations |

| Epidermolysis bullosa simplex with underlying psychiatric component | Chronic depression and chronic pain from epidermolysis bullosa |

| Neurotic excoriations | Obsessive compulsive disorder with neurotic excoriations |

| Morgellons | Delusions of parasitosis |

| Axillary pruritus | Generalized pruritus likely secondary to adjustment disorder with anxiety |

| Trichotillomania | Trichotillomania, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, anxiety, depression |

| Atopic dermatitis with pruritus | Atopic dermatitis with generalized anxiety disorder |

| Stress induced urticaria | Urticaria with generalized anxiety disorder |

| Prurigo nodularis | Neurotic excoriations and prurigo nodularis with severe anxiety disorder |

| Prurigo nodularis | Prurigo nodularis in the setting of folliculitis and generalized anxiety disorder |

Treatment plans included the initiation of an anxiolytic, antidepressant, and/or antipsychotic medication, psychotherapy, and a combination or continuation of these (Table 2).

Table 2.

Therapeutic strategies

| Dose change (n) | Initiation (n) | Continuation (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiolytic | 3 | 1 | |

| Antidepressant | 1 | 6 | 4 |

| Antipsychotic | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Psychotherapy | 9 | 4 |

Discussion

Delusions of parasitosis was the most commonly referred condition. Building a rapport, ruling out other diagnoses, and performing appropriate laboratory tests are imperative (Brown, Malakouti, Sorenson, Gupta and Koo, 2015, Patel and Koo, 2015). Neurotic excoriations should be investigated similarly (Brown et al., 2015). Both conditions require pharmacologic treatment for any underlying psychiatric disorders but also an earnest commitment to “optimize trust and therapeutic rapport with the patient” (Brown et al., 2015). When appropriate, the physician can perform a biopsy to help reduce uncertainty and further strengthen the patient-doctor relationship but only after clearly setting expectations.

Clearance to initiate isotretinoin in patients with a history of suicide attempts or depression is a commonly encountered issue in the management of patients with severe acne vulgaris. There is no increased risk of depression and suicidality in patients with nodulocystic acne being treated with isotretinoin (Brown et al., 2015). Rather, they are more likely to report that their mood has improved during treatment with isotretinoin (Brown et al., 2015). However, patients with a family or personal history of mental disorders may experience a worsening of depression during the course of isotretinoin treatment (Oliveira et al., 2018). For these patients, establishing appropriate follow-up is important.

Referral diagnoses were changed or expanded in almost half of the patients who were seen at the psychodermatology clinic, which highlights the utility of having a clinic with specialists. Patients can be thoroughly investigated for confounders such as socioeconomic factors and prescription and/or recreational drug use when appropriately discussed and thoughtful treatment plans can be proposed. These findings also suggest that underlying psychologic conditions can result in cutaneous manifestations, primary cutaneous disorders can lead to psychological distress, and the coexistence of cutaneous disease and psychological conditions can result in exacerbations of both conditions.

The clinic did encounter some challenges. Some patients were reluctant to be interviewed by psychiatry providers. The need to pay two copays at once also hindered affordability for some patients. Additionally, despite limited availability, we did have a high cancellation/no-show rate, which was detrimental to those waiting to be seen.

Conclusions

Psychodermatology is a unique area of dermatologic practice in which many dermatologists do not feel comfortable. By creating a monthly clinic for dermatology patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, we are able to meet the needs of these patients without the burden of multiple appointments and access related challenges. This offers an interdisciplinary way to manage overlapping medical conditions and helps patients feel that providers are working synergistically (Marshall et al., 2016).

Patients with significant comorbid psychiatric and dermatologic disorders may also benefit from being seen in these combined clinics. Although two copays were required at the visit, the overall cost for the patient is ultimately reduced because patients do not have to travel to the office for two separate visits. Challenges associated with the implementation of this clinic included patient reluctance to see an interdisciplinary team and adherence to scheduled appointments. Given the need for multiple follow-up appointments, this can be particularly problematic.

Diagnoses were changed or clarified upon in almost half of the patients. This may reflect both the need for specific expertise and the time that is needed to evaluate these complex comorbid conditions. Finally, emphasizing education by including training physicians along with expanding combined teaching clinics such as ours can potentially help build expertise in the complex realm of psychodermatology.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This article does not have a funding source.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

IRB status: This retrospective study was approved by an institutional review board.

References

- Brown G.E., Malakouti M., Sorenson E., Gupta R., Koo J.Y. Psychodermatology. Adv Psychosom Med. 2015;34:123–134. doi: 10.1159/000369090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke D.C., Keeley M.L., Geffken G.R., Storch E.A. Trichotillomania: A current review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- França K., Castillo D.E., Roccia M.G., Lotti T., Wollina U., Fioranelli M. Psychoneurocutaneous medicine: Past, present and future. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2017;167:31–36. doi: 10.1007/s10354-017-0573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafferany M., Franca K. Psychodermatology: Basics concepts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(217):35–37. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafferany M., Vander Stoep A., Dumitrescu A., Hornung R.L. The knowledge, awareness, and practice patterns of dermatologists toward psychocutaneous disorders: Results of a survey study. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(7):784–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C., Taylor R., Bewley A. Psychodermatology in clinical practice: Main principles. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(217):30–34. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira J.M., Sobreira G., Velosa J., Telles Correia D., Filipe P. Association of isotretinoin with depression and suicide: A review of current literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(1):58–64. doi: 10.1177/1203475417719052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., Koo J.Y. Delusions of parasitosis: Suggested dialogue between dermatologist and patient. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(5):456–460. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2014.996513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S., Narang T., Kumaran M.S. Psychodermatology: A comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(2):176–192. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.107632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]