Abstract

Context:

Synchronous Bilateral Wilms tumor (sBWT).

Aims:

This study aimed to assess the outcome of patients with sBWT treated on SIOP protocol.

Settings and Design:

Retrospective and prospective randomized study.

Subjects and Methods:

SIOP 93-01 protocol was used to study nine patients of sBWT in a single center and followed up over a period from 2 to 5 years.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Unpaired t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used for analysis.

Results:

Of nine patients, six were included in the study as three patients lost to follow-up. Among the six patients, there were four girls and two boys with a median age of 2 years. Mean regression in the size of tumor was 87% in four out of six patients. Tumor with unfavorable histology showed 32% response (ratio of favorable: unfavorable histology 2:1). Event-free survival rate was 81.3% and overall survival was 90% over 2–5 years. Recurrence was seen in two patients of whom one had Denys–Drash syndrome. Mean DTPA glomerular filtration rate was 91.4/ml/min/1.73 m2 preoperatively and that of 3 months after completion of treatment was 84/ml/min/1.73 m2. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) using Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory and Lansky Play Performance Scale revealed significant improvement results of all functioning domains such as physical, social, emotional, and school subscales with P < 0.05 and performance scale (P < 0.04).

Conclusions:

We suggest SIOP protocol for sBWT and bilateral nephron-sparing surgery in two stages. However, long-term follow-up is required to assess the ultimate renal function outcome. HRQOL is an essential guide in improving the conditions of pediatric cancer survivors.

KEYWORDS: Nephron-sparing surgery, preoperative chemotherapy, synchronous bilateral Wilms tumor

INTRODUCTION

Wilms tumor is the most common malignant renal tumor and third most common tumor of childhood. It may be unilateral or bilateral, synchronous or metachronous. Synchronous bilaterality accounts for 4%–8% of all Wilms tumors.[1,4,15,20,22,25,27,30] Management of Wilms tumor has been accomplished by either following the NWTSG protocol or the SIOP according to institutional preferences. Both these groups because of their extensive study have their own merits. In India, very few studies have been reported on SIOP protocol till date. Our aim was to study the occurrence of synchronous bilateral Wilms tumor (sBWT) with age at presentation, sex, religion, socioeconomic status, response to chemotherapy, types of surgery, postoperative histopathology, event-free survival, and overall survival. To assess the renal function status preoperatively, after surgery, and at follow-up and to assess the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) after completion of treatment, we followed the SIOP 93-01 protocol in our study.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

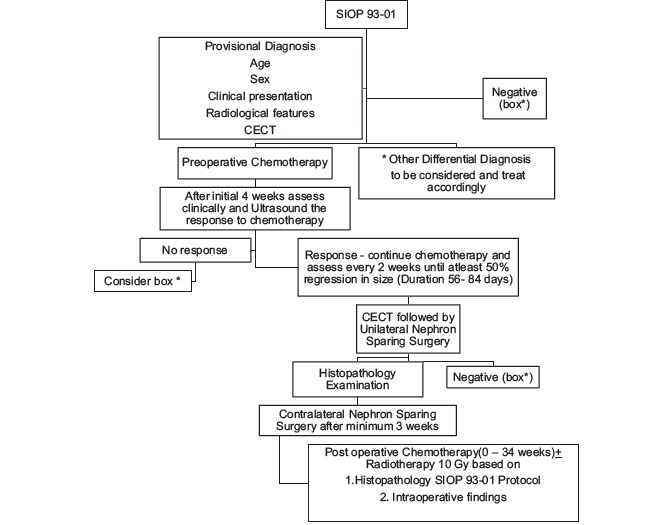

This is a retrospective and prospective randomized study from January 2012 to January 2017 conducted in the Department of Paediatric Surgery, Nilratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata. At our institution, we encountered sixty cases of Wilms tumor over 5 years of which nine cases were sBWT. Three patients had to be excluded as they lost to follow-up either receiving few cycles of chemotherapy or after diagnosis. The total numbers of participants included were six patients (four girls and two boys). Diagnosis was made based on clinical examination with presence of abdominal lump with or without pain, fever, hematuria, or associated anomalies and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen and thorax. CECT findings of Wlms tumor usually show thin rim of capsule or pseudocapsule, with or without calcifications, intravascular thrombus and absence of encasement, and presence of lymph nodes.[18,31] Routine blood investigations included complete blood count, liver function tests, serum creatinine, serum electrolytes, and urine reports. None of our patients had radiologically detectable distant metastasis. All the patients were subjected to SIOP 93-01 protocol.[12,13,22,30] BWT being Stage V tumor, longer pretreatment with chemotherapy is preferred.[15,19,22,30] Preoperative chemotherapy was started with two drugs namely vincristine (1.5 mg/m2) and dactinomycin (15 μg/kg/day) and regression in tumor size was assessed after 4 weeks clinically and by ultrasound. In tumor which showed unsatisfactory response, doxorubicin (45 mg/m2) was added to achieve tumor response after consultation with the medical oncology department.[27] The duration of chemotherapy ranged from 56 to 84 days. No chemotherapy was given beyond 12 weeks.[19,26,30,27] This was followed by CECT whole abdomen to assess final regression in size of the tumor and resectability. Dosage was reduced to half for children < 12 months. Then, unilateral nephron-sparing surgery (NSS) was performed for the side with larger size tumor. Contralateral side was explored for NSS within 3–4 weeks. In cases of multiple small size tumor involving either or both kidneys, only tumorectomy was done for one kidney at a time[2,3,4] [Chart 1].

Chart 1.

Algorithm of management of Bilateral Wilms Tumour based on SIOP 93-01. * Other Differential Diagnosis to be considered and treat accordingly

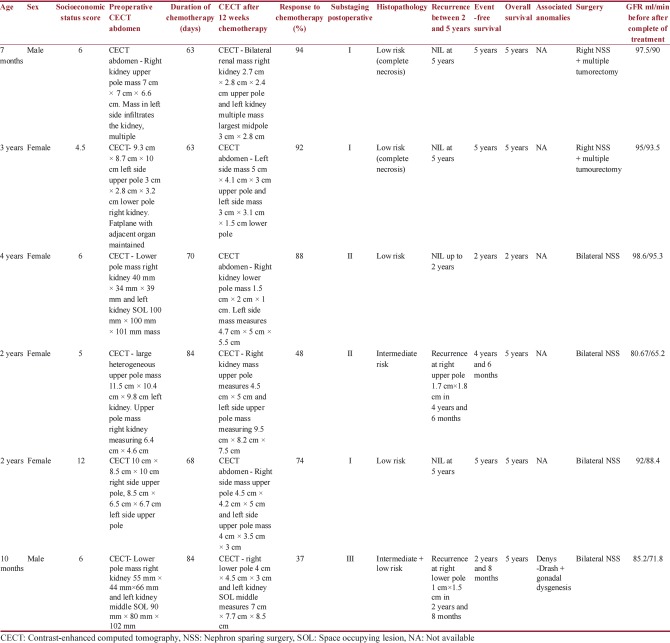

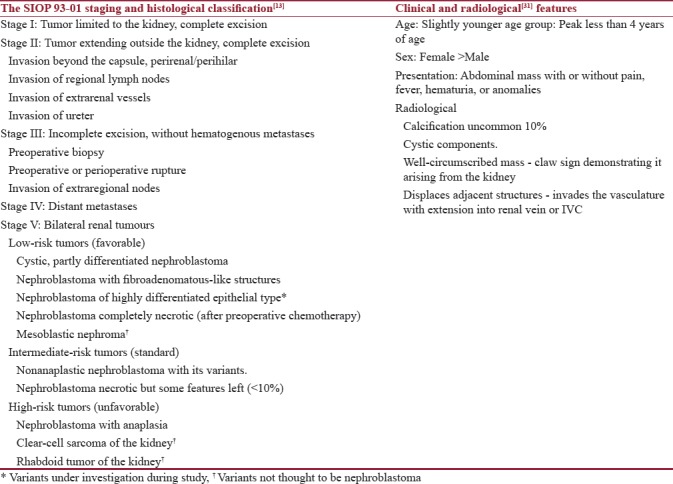

Further treatment was based on clinical staging at surgery and histopathology of sBWT. This was followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Patients with Stage III tumor received local radiotherapy in the tumor bed. Staging and histology were as per SIOP 93-01 classification[13,19,22] [Table 1]. Radiation dose of total 10 Gy was administered. All the patients received adjuvant chemotherapy for 0–34 weeks with vincristine, dactinomycin, and/or doxorubicin as when deemed necessary and other drugs after consultation with medical oncology department. Renal function status was assessed with Tc-99mDTPA scan prior to surgery and 3 months after bilateral NSS and at follow-up yearly, and the total glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was noted[23] [Table 2]. In the interval between the two surgeries, renal function assessment was made with serum creatinine level. The upper limit of normal creatinine level was taken as 1.5 mg/dl.

Table 1.

Staging and histological classification according to SIOP 93 01 protocol with Clinical and radiological features of bilateral Wilms tumor

Table 2.

Demographic data and management outcomes of synchronous bilateral Wilms tumor as per SIOP 93-01

Patients were followed up for 2–5 years. Six patients were followed up, of which one patient could be followed up for 2 years. One patient had Denys–Drash syndrome (DDS) with gonadal dysgenesis. The percentage of preserved renal mass after surgical resections was estimated from the surgical, pathological, and imaging reports. At least 2/3rd of the functional mass was attempted to be preserved in either of the kidneys in cases of large tumor involving one kidney.

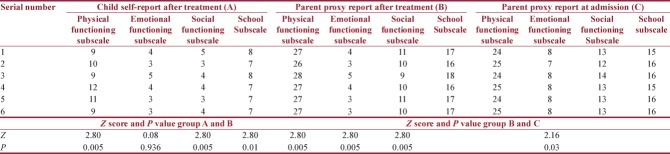

All the patients were evaluated for HRQOL at initial admission and during follow-up after completion of treatment when the toxic effects of the drugs were assumed to have been reduced and thereafter 3 monthly. HRQOL was assessed using Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 4.0™.[8] Children below 5 yrs of age fail to appreciate, interpret & communicate their emotions, physical and functional activities properly. This is one limitation of the scoring scale. Secondly, in children below 2 yrs, the parents are unable to appropriately document the same parameters in their proxy report. Performance status was evaluated by using the Lansky Play Performance Scale. This scale is appropriate for children aged 1-16 yrs. Hence by the time patients were followed up, majority attained their desired age to be fit for assessment.[7,8,10,17,24,28] Socioeconomic status was evaluated using the Kuppuswamy scale.[33] Event-free survival was defined as time from first follow-up to the first occurrence of progression, recurrence after response, or death from any cause. Overall survival was defined as time from entry to death from any cause.[21]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was done using Microsoft Excel for calculating the mean, median, and standard deviation for demographic data. Unpaired t-test was used for categorical data and Mann–Whitney U-test was used for nonparametric continuous variables in the assessment of quality of life.

RESULTS

Out of nine patients of sBWT, three patients were excluded as they did not meet the eligibility criteria. Among six patients, four girls and two boys (ratio 2:1) could be followed up for postsurgery and postchemotherapy outcomes in respect of event-free survival, overall survival, and HRQOL. Only one female patient had a short follow-up of 2 years. Median follow-up was 5 years. Median age at presentation was 2 years. There was no difference noted in outcomes in relation to socioeconomic status or religion. Majority of the patients belonged to Kuppuswamy Class 4 with a median score of 6 [Table 2].

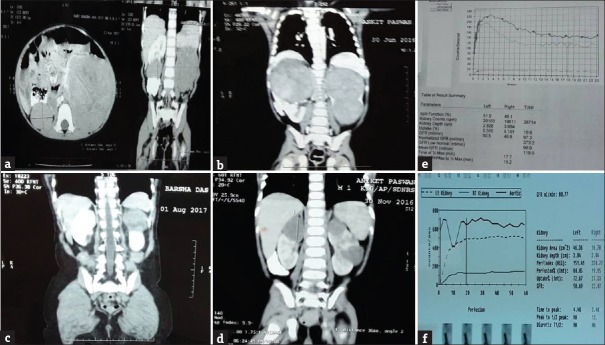

Response to chemotherapy was noted as this was the most important aspect in SIOP protocol. Mean regression in the size of the tumor was 87% in four out of six patients with 12 weeks of chemotherapy. Nearly 70% of the participants responded well to chemotherapy and showed more than 50% response to chemotherapy [Figure 1]. In two patients, tumor response was slow with mean regression (32%) which could be correlated with postoperative histological findings. Four patients received two-line chemotherapy preoperatively, while two received three-line chemotherapy.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Preoperative chemotherapy contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan. (c and d) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography after 63 days and 70 days chemotherapy. (e and f) Preoperative and postoperative DTPA scan

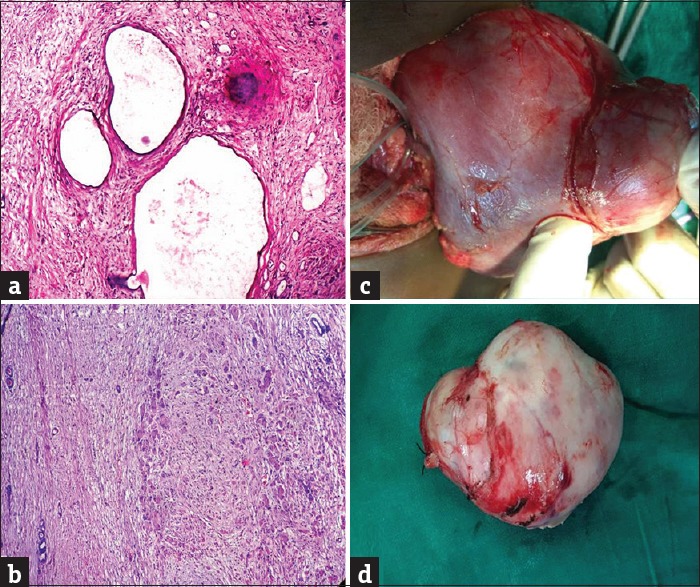

One patient had recurrence at 4 years and 6 months after completion of therapy and the second patient had recurrence at 2 years and 8 months. Tumor that showed recurrence had intermediate-risk histology and one had associated DDS. Three patients with sBWT were Stage I, two patients were Stage II, and one with Stage III. One patient with Stage II had intermediate-risk histology type on both sides and 1 with Stage III had intermediate-risk stromal type on one side and low-risk histology on the other side [Figure 2]. Complete necrosis was found in two low-risk tumors. None of the cases reported with metastasis or showed anaplasia on histopathology. Serum creatinine remained within normal range after initial surgery and after completion of treatment. Mean DTPA GFR was 91.4/ml/min/1.73 m2 preoperatively and that of 3 months after completion of treatment was 84/ml/min/1.73 m2 [Table 2].

Figure 2.

(a) Low-risk tumor, composed of dilated, cystic spaces lined by flattened epithelium. (b) Intermediate-risk tumor, stromal type (H and E, ×40). (c) Nephron-sparing surgery. (d) Nephrectomy specimen

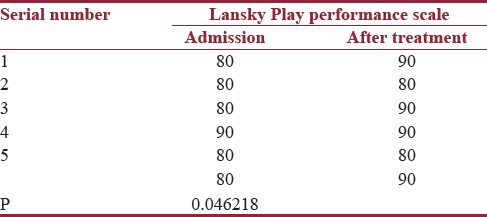

HRQOL was assessed in our study to understand patient response to therapy. Lansky Play Performance Scale was used before and after treatment. Median score was 80 at the time of admission and it improved to 90 after treatment (P < 0.04622 and P < 0.05, significant) [Table 3]. PedsQL was used at admission and after completion of chemotherapy in follow-up patients. Both child self-score and parent proxy report were assessed in response to physical, emotional, social, and school subscales. Due to limitations of the scoring system, comparison between parent reports with individual variables before and after treatment and between child and parent report after treatment was done separately. In parent proxy report, results were significant for all functioning domains before and after treatment (P < 0.05). When child self-report was compared with parent proxy report after treatment, a significant association was observed in physical, social, and school subscales, but emotional functioning revealed insignificant value (P = 0.93624 and P > 0.05) [Table 4]. Event-free survival was 81.3% and overall survival was 90% over 2–5 years. There was null mortality.

Table 3.

Lansky Play Performance scale

Table 4.

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory assessment of quality of life before and after treatment (Mann-Whitney U-test, Z-score, and P<0.05, significant)

DISCUSSION

Bilateral Wilms tumor has always been a challenge in management as it involves not only removal of the tumor, but also preventing its recurrence and at the same time preserving the renal function. Since the origin of NWTSG in 1969 and SIOP in 1971, many trials have been performed for improving the treatment and overall survival of Wilms tumor.[15,19,20,21,27] sBWT possesses the threat of postoperative end-stage renal failure with initial surgery as < 50% of the renal parenchyma could be preserved. Until recently, it has been found that with preoperative chemotherapy, preservation of renal parenchyma is possible. In SIOP protocol, preoperative chemotherapy has been the mainstay although the duration of the treatment has never been defined. In our study, we started with two-line drug vincristine and actinomycin D for all sBWT patients; however, two patients with slow response received additional drug doxorubicin. Our findings corroborate with previous studies.

Imaging has been the cornerstone of SIOP which avoids the risk of preoperative upstaging of the tumor. Sudour etal reported 49 cases of sBWT of which 98% cases were diagnosed by CT imaging.[22] Similar findings in our study enable us to conclude CT scan as the investigation of choice for sBWT. Overall survival outcome with preoperative chemotherapy in earlier studies on SIOP has been 75%–90% with follow-up from 3 to 10 years. In our study, we also had a similar finding which gave us the confidence to prolong the chemotherapy to achieve adequate response so as to save as much renal parenchyma as possible. The mean duration of preoperative chemotherapy was 72 days followed by CECT abdomen to assess the response and feasibility of NSS. Boccon-Gibod et al. suggested that continuing chemotherapy > 12 weeks is unlikely to facilitate resection and maximum tumor shrinkage occurred in the first 12 weeks.[9] Although no complications were reported with preoperative chemotherapy, we did not prefer to continue further as we achieved > 50% regression in size of tumor in majority of the cases.

All the six patients had two-step NSS with an interval of 4 weeks. Further adjuvant chemotherapy was based on surgical staging and histopathology as per SIOP 93-01 protocol. Sudour et al. found that functional outcome significantly improved after bilateral NSS, but did not compare the results with one- and two-step surgeries.[22] Del Angel Gracia reported a case report on bilateral Wilms tumor that underwent an uneventful recovery after bilateral NSS.[25] Sarhan et al. stated in their retrospective study that children with Wilms tumor are at greater risk of renal failure due to either chemotherapeutic drugs or secondary to hyperfiltration injury of the residual nephrons after NSS.[20] In our study, we performed two-step surgery and found no tumor recurrence by assessing with CECT prior to second surgery. Moreover, chemotherapy helped us with a clear plane of dissection and decreased vascularity and there was no capsular breach. Thus, we support that NSS has the advantage of retaining even the slightest of the functioning kidney available.[2,6,5]

Renal function status is very important as bilateral nephrectomy results in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) with or without renal transplantation found in most of the studies.[3,29] Hence, renal-preserving surgery has evolved. Breslow et al. reported the cumulative incidence of ESRD in sBWT as 11.5% at 20 years who underwent either nephrectomy or partial nephrectomy.[16] In their series of 49 patients with sBWT over 8 years, Sudour et al. reported that 68% underwent NSS of which 14% of patients developed ESRD.[22] Sosnowski et al. found in their study on twenty patients with NSS for renal tumor that only four patients had significant deterioration in renal function after comparing the mean GFR.[23] Costabel et al. in their study on 45 patients with NSS for solitary kidney tumor over 10 years found significantly lower calculated GFR after surgery with loss of renal mass and male gender.[32] In our study, we found decrease in 5%–8% mean GFR after completion of treatment, but it is yet to be concluded in a short follow-up because ESRD may be seen later.

Age, sex, socioeconomic status, histology, and tumor stage correlated with sBWT. We found a female preponderance and a younger age in sBWT. Socioeconomic status did not have any effect in the treatment and management. Other factors that have contributed to the outcome of the disease were histology of the tumor, associated anomalies, and understaging of tumor. In our study, we had four patients with low-risk histology and two patients with intermediate-risk histology and one had DDS. Sudour et al. found seven patients with relapse, of which four underwent NSS in one kidney and had associated intermediate-risk histology and associated anomalies, and metastasis occurred in one patient after nephrectomy.[22] In their series of thirty adult patients on SIOP 93-01, Reinhard et al. found that relapse occurred in four high-risk histology patients with liver, lung, and cervical lymph node metastasis.[14] Haecker et al. compared the results of patients on SIOP 93-01 protocol that underwent NSS and total nephrectomy and found that relapse-free survival rate showed no significant difference after total nephrectomy or NSS; however, two patients with intermediate-risk histology showed relapse after NSS.[11] Our findings showed two recurrences as shown in Table 2, both of them had local recurrence and alive without any metastasis over 5-year period. As sizes of the tumor were < 2 cm, we preferred chemotherapy for 12 weeks followed by radiation in the tumor bed after discussion with medical oncology department. In one patient, there was no tumor noted after CECT at 1 year after treatment, the other with DDS is still under follow-up. Effects due to understaging were unlikely as the course of adjuvant chemotherapy was based on the highest histological grading and surgical staging.

Patrick and Erickson defined HRQOL as a value assigned to duration of life modified by impairments, functional states, perceptions, and social opportunities that are influenced by disease, injury, treatment, or policy.[7] Various scoring systems based on questionnaires have evolved to the need for a standardized system. Quality of life has therefore become a significant aspect for cancer patients as much information could be gathered that helps us to improve their condition. sBWT being a rare presentation has impelled us to use the scoring system. Batra et al. had used Health Utility Index-2 and Lansky Play Performance Scale for the assessment of HRQOL in 75 pediatric cancer patients and found significant differences before and after initiation of therapy.[28] Yağci-Küpeli et al. described the validation of PedsQL 4.0™ and Generic Score Scale in 302 pediatric cancer survivors.[24] Nathan et al. found adverse outcomes in adult survivors of childhood Wilms tumor and neuroblastoma using Short Form health Survey for assessing HRQOL.[17] In our study, performance status showed significant improvement with initiation of therapy. There was also significant improvement in quality of life after treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

sBWT being a rare presentation with higher recurrence rate and postoperative renal failure needs strict protocol follow-up. Our study has limitations because we had a short follow-up of 5 years and smaller number of patients. We suggest SIOP protocol as this avoids unnecessary early surgery or biopsy; response to chemotherapy is excellent in most cases and more than 50% of renal parenchyma can be preserved. Bilateral NSS in two stages should be the procedure of choice; however, long-term follow-up is required to assess the renal function. HRQOL is an essential guide in improving the conditions of pediatric cancer survivors and provides them a new dimension of life.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeLorimier AA, Belzer FO, Kountz SL, Kushner J. Treatment of bilateral Wilms' tumor. Am J Surg. 1971;122:275–81. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(71)90330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop HC, Tefft M, Evans AE, D'Angio GJ. Survival in bilateral Wilms' tumor – review of 30 national Wilms' tumor study cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1977;12:631–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(77)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeMaria JE, Hardy BE, Brezinski A, Churchill BM. Renal transplantation in patients with bilateral Wilms' tumor. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:577–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(79)80143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laberge JM, Nguyen LT, Homsy YL, Doody DP. Bilateral Wilms' tumors: Changing concepts in management. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:730–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(87)80615-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longaker MT, Harrison MR, Adzick NS, Crombleholme TM, Langer JC, Duncan BW, et al. Nephron-sparing approach to bilateral Wilms' tumor: In situ or ex vivo surgery and radiation therapy. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:411–4. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(90)90382-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaul DB, Srikanth MM, Ortega JA, Mahour GH. Treatment of bilateral Wilms' tumor: Comparison of initial biopsy and chemotherapy to initial surgical resection in the preservation of renal mass and function. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:1009–14. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90548-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patrick DL, Erickson P. Health Status and Health Policy: Quality of Life in Health Care Evaluation and Resource Allocation. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL: Measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care. 1999;37:126–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boccon-Gibod L, Rey A, Sandstedt B, Delemarre J, Harms D, Vujanic G, et al. Complete necrosis induced by preoperative chemotherapy in Wilms tumor as an indicator of low risk: Report of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) nephroblastoma trial and study 9. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;34:183–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(200003)34:3<183::aid-mpo4>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yariş N, Yavuz MN, Yavuz AA, Okten A. Assessment of quality of life in pediatric cancer patients at diagnosis and during therapy. Turk J Cancer. 2001;31:139–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haecker FM, von Schweinitz D, Harms D, Buerger D, Graf N. Partial nephrectomy for unilateral Wilms tumor: Results of study SIOP 93-01/GPOH. J Urol. 2003;170:939–42. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000073848.33092.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinhard H, Semler D, Bürger D, Bode U, Flentje M, Göbel U, et al. Results of the SIOP 93-01/GPOH trial and study for the treatment of patients with unilateral nonmetastatic Wilms tumor. Klin Padiatr. 2004;216:132–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-822625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Kraker J, Graf N, van Tinteren H, Pein F, Sandstedt B, Godzinski J, et al. Reduction of postoperative chemotherapy in children with stage I intermediate-risk and anaplastic Wilms' tumour (SIOP 93-01 trial): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1229–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinhard H, Aliani S, Ruebe C, Stöckle M, Leuschner I, Graf N, et al. Wilms' tumor in adults: Results of the society of pediatric oncology (SIOP) 93-01/Society for pediatric oncology and hematology (GPOH) study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4500–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metzger ML, Dome JS. Current therapy for Wilms' tumor. Oncologist. 2005;10:815–26. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-10-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breslow NE, Collins AJ, Ritchey ML, Grigoriev YA, Peterson SM, Green DM, et al. End stage renal disease in patients with Wilms tumor: Results from the national Wilms tumor study group and the united states renal data system. J Urol. 2005;174:1972–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176800.00994.3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nathan PC, Ness KK, Greenberg ML, Hudson M, Wolden S, Davidoff A, et al. Health-related quality of life in adult survivors of childhood Wilms tumor or neuroblastoma: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:704–15. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickson PV, Sims TL, Streck CJ, McCarville MB, Santana VM, McGregor LM, et al. Avoiding misdiagnosing neuroblastoma as Wilms tumor. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1159–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhatnagar S. Management of Wilms' tumor: NWTS vs. SIOP. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14:6–14. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.54811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarhan OM, El-Baz M, Sarhan MM, Ghali AM, Ghoneim MA. Bilateral Wilms' tumors: Single-center experience with 22 cases and literature review. Urology. 2010;76:946–51. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton TE, Ritchey ML, Haase GM, Argani P, Peterson SM, Anderson JR, et al. The management of synchronous bilateral Wilms tumor: A report from the national Wilms tumor study group. Ann Surg. 2011;253:1004–10. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821266a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudour H, Audry G, Schleimacher G, Patte C, Dussart S, Bergeron C, et al. Bilateral Wilms tumors (WT) treated with the SIOP 93 protocol in France: Epidemiological survey and patient outcome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:57–61. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sosnowski R, Benke M, Demkow T, Ligaj M, Michalski W. Renal function after nephron-sparing surgery for renal tumors. Cent European J Urol. 2012;65:14–6. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2012.01.art4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yağci-Küpeli B, Akyüz C, Küpeli S, Büyükpamukçu M. Health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors: A multifactorial assessment including parental factors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:194–9. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182467f5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Angel Gracia XE. Bilateral Wilms Tumor with areas of focal anaplasia: A case report. Rev Mex Urol. 2013;73:287–91. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrer FA, Rosen N, Herbst K, Fernandez CV, Khanna G, Dome JS, et al. Image based feasibility of renal sparing surgery for very low risk unilateral Wilms tumors: A report from the children's oncology group. J Urol. 2013;190:1846–51. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Özyörük D, Emir S. The management of bilateral Wilms tumor. Transl Pediatr. 2014;3:34–8. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2014.01.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batra P, Kumar B, Gomber S, Bhatia MS. Assessment of quality of life during treatment of pediatric oncology patients. Indian J Public Health. 2014;58:168–73. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.138623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Sylvester R, Campbell S, Van Poppel H. Renal function after nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy: Results from EORTC randomized trial 30904. Eur Urol. 2014;65:372–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Godzinski J. The current status of treatment of Wilms' tumor as per the SIOP trials. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2015;20:16–20. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.145439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dumba M, Jawad N, Mchugh K. Neuroblastoma and nephroblastoma: A radiological review. Cancer Imaging. 2015;15:5. doi: 10.1186/s40644-015-0040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costabel JI, Marchinena PG, Tirapegui F, Dantur A, Jurado A, Gueglio G, et al. Functional and oncologic outcomes after nephron-sparing surgery in a solitary kidney: 10 years of experience. Int Braz J Urol. 2016;42:253–61. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2014.0463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaikh Z, Pathak R. Revised Kuppuswamy and NG Prasad socio-economic scales for 2016. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;4:997–9. [Google Scholar]