Abstract

Background

alcohol presents risks to the health of older adults at levels that may have been ‘safer’ earlier in life. Moderate drinking is associated with some health benefits, and can play a positive role in older people’s social lives. To support healthy ageing, we must understand older people’s views with regards to their drinking. This study aims to synthesise qualitative evidence exploring the perceptions and experiences of alcohol use by adults aged 50 years and over.

Methods

a pre-specified search strategy was applied to Medline, PsychINFO, Scopus, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature databases from starting dates. Grey literature, relevant journals, references and citations of included articles were searched. Two independent reviewers sifted articles and assessed study quality. Principles of thematic analysis were applied to synthesise the findings from included studies.

Results

of 2,056 unique articles identified, 25 articles met inclusion criteria. Four themes explained study findings: routines and rituals of older people’s drinking; self-image as a responsible drinker; perceptions of alcohol and the ageing body; and older people’s access to alcohol. Differences between gender, countries and social patterns are highlighted.

Conclusions

older people perceive themselves as controlled and responsible drinkers. They may not recognise risks associated with alcohol, but appreciate its role in sustaining social and leisure activities important to health and well-being in later life. These are important considerations for intervention development. Drinking is routinised across the life course and may be difficult to change in retirement.

Keywords: alcohol, older people, perceptions, qualitative thematic synthesis, systematic review

Introduction

Alcohol consumption is causally-linked to over 60 disease-conditions, many of which are common in older age, including cardiovascular disease, dementia and various cancers [1]. Drinking up to 14 units of alcohol per week, spread evenly over three or more days is considered to be lower-risk for developing these diseases [2]. However, physiological tolerance for alcohol decreases with age [3–6], increasing risks attached to using alcohol at levels that would have been ‘safer’ at earlier stages in life [7, 8]. Many older adults also live with multiple health conditions and take a range of prescribed medications to manage them. Some of these conditions and medications can be affected by alcohol use [9]. Older adults are therefore likely to be effected more by alcohol, and must take extra care with their drinking [2].

Alcohol misuse is a particular issue in higher income countries, including amongst older people, where relatively greater income supports the purchase of alcohol [10, 11]. Consequently, within these countries public health campaigns and clinical practice have targeted later life alcohol misuse [11]. Older adults have not responded to these campaigns, maintaining levels of risky drinking where the rest of the population has reduced their intake and associated risks [4, 12–14]. Across higher income countries, up to 45% of older people who drink do so at levels which may be harmful to their health [10]. Older adults are facing increasing health issues linked to their drinking [15–18], and these numbers will continue to grow as the population ages [19]. However, most older adults experiencing harm from their drinking would not view themselves as problematic drinkers [7], as despite drinking more frequently than younger age groups, older people tend to drink to less dramatic excess, where risks are less visible [12, 20, 21]. Policy makers and health and social care workers fail to recognise alcohol-related harm amongst the older age group as a consequence [22]. Social patterns in older people’s drinking illuminate at-risk groups; for example, hazardous older drinkers are more likely to be male [10, 23–25] and less socioeconomically deprived [24]. Patterns of drinking can also vary between different countries [10, 23]. Particular ethnicities such as Europeans (particularly Irish) and Maori’s are more likely to drink at risky levels [10, 25, 26] as cultural and religious proscriptions shape attitudes towards alcohol [27–29].

Alcohol can play a positive role in many older people’s social lives [16, 30–33], and there may be some health benefits at lower-levels of intake [34–40]. Qualitative studies provide the most appropriate approach to enhancing our understanding of older people’s reasons behind their drinking practices. This study aims to identify and synthesise qualitative data on older people’s views and experiences of drinking in later life to explore reasons for, and factors shaping, older people’s drinking in higher income countries. Recognising these reasons and exploring how socio-demographic factors shape older people’s alcohol use in higher income countries will ensure that public health policy makers and clinical practitioners, within the UK and more widely, are able to respond to the reasons behind older people’s drinking and target appropriate groups.

Methods

Search strategy

Five bibliographic databases were searched from start date to March 2016 (Medline (1946), PsychINFO (1806), Scopus (1960), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL, 1984) and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA, 1987)). Database-specific headings and key words were developed relating to the concepts ‘older adults’, ‘drinking’, ‘qualitative’ and ‘perceptions and experiences’. The search terms for this review were developed applying the Joanna Briggs Institute’s recommendations for qualitative systematic reviews [41]. For Medline, key words were mapped to related medical subject headings (MeSH), which were exploded, focussed, and combined appropriately, alongside key words. This produced a search strategy optimised for sensitivity (tested for inclusion of known relevant articles) and specificity. The following grey literature sources were searched, applying key terms: NHS evidence, Open Grey and Dissertation Abstracts International. The full search strategy applied to each database within this review is available through our Prospero registration [42]. The reference list and citations of included articles were searched for further eligible articles.

Eligibility criteria

Published studies and theses in any language presenting qualitative analysis. No time limits were applied other than those imposed by the limits of the database. Reviews and case studies were excluded.

Studies with a focus on the views of older adults, defined for the purpose of this review as aged 50 years and over. This is the earliest age frame specified by studies focussing on later life.

Studies reporting perceptions and experiences of alcohol consumption in later life.

Studies focusing on the views of individuals living in higher income countries.

Studies specifically focused on individuals who were known to be dependent were excluded as such treatment populations are strongly encouraged to abstain from drinking.

Studies where alcohol use could not be distinguished from other substance use were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Following electronic de-duplication of articles, two independent reviewers screened papers for relevance based on titles and abstracts. Full text versions of selected papers were then assessed for inclusion within this review. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved, or referred to a third team member. Non-English titles/abstracts were translated online to assess eligibility. The findings of non-English full text papers were translated by individuals bilingual in the language and English. Authors were contacted when articles were irretrievable online.

Details of the study setting, participants, methods and study data were extracted from articles selected for inclusion. Study quality was assessed by two independent reviewers using Saini and Schlonsky’s Qualitative Research Quality Checklist [43]. Studies were not excluded on the basis of quality appraisal, as poor reporting is not necessarily indicative of poorly conducted research [43]. However, assessing quality prevents unreliable results from influencing the review findings [44]. Key limitations and comments on richness of presented findings are detailed for each study in Table 1 (see Table 3 in Appendix 1, available at Age and Ageing online for full summary of appraisal) and summarised within our study descriptions to give a sense of the limitations and richness of data available in this field.

Table 1.

Brief descriptive summaries of included studies with key limitations identified in quality appraisal

| Article and country | Aims | Sample | Data collection methods and analysis | Author-identified key themes | Key limitations and comment on richness from quality appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aitken [59], New Zealand | To understand the meanings of alcohol use for older people who use alcohol and to understand older people’s reasons for drinking and identify the discourses they draw on to construct their alcohol use. | n = 18, Age = 53–74 years, Drinking status = responsible and potentially hazardous drinkers. | Semi-structured interviews, Discourse analysis | A ‘social life’ discourse; A ‘drinking to relax’ discourse; The ‘health issue’ discourse; A ‘problem’ discourse | Lack of transparency in reporting; thick description in places with some contextual details presented and many exemplary quotes |

| Billinger et al. 2012 [60], Sweden | Examines how older adults reason their relationship with alcohol and how they see the boundaries between what is acceptable and unacceptable drinking | n = 20, Age = 61–70 years, Drinking status: not reported. | Focus groups, Hermeneutic interpretation analysis | How the participants described the role of alcohol in their childhood; How participants described their first experience with alcohol; The participants’ definition of their current alcohol consumption; The boundary between acceptable and unacceptable alcohol use; Other people’s means of dealing with alcohol | No exploration of author biases presented; thick description rich with contextual detail, characteristics and trends. |

| Bobrova et al.[67], Russia | Investigated gender differences in drinking patterns and the reasons behind them among men and women in the Russian city of Novosibirsk | n = 44, Age = 48–63 years, Drinking status = abstainers, occasional drinkers, frequent drinkers and heavy drinkers. | Semi-structured interviews, Framework approach and inductive and thematic analysis | Traditional drinking patterns; Individual drinking patterns; Perceived reasons behind the gender differences in drinking | Lack of transparency in reporting; thinner description with some details presented of sample and context linked to study findings. |

| Burruss et al.[53], the USA | Exploring alcohol use among a subpopulation of older adults in congregate living, specifically a continuing care retirement community | n = 11, Age = 68–90 years, Drinking status = regular drinkers. | In-depth interviews, Thematic analysis | Drinking as habit/routine; Peers as catalysts for increased consumption; Alcohol use and congregate living | Lack of transparency in reporting; thick description of study findings supported with contextual detail. |

| Dare et al.[61], Australia | To explore

|

n = 44, Age = 65–74 years, Drinking status = frequent drinkers, mostly low risk. | In-depth interviews, Thematic analysis | Alcohol and social engagement; Alcohol and relaxation; Alcohol, work and leisure; Social engagement; Social norms; Self-imposed regulations; Driving; Convenient and regular access to social activities; Driving and setting | Inconsistent transparency in reporting; thick description of study findings exploring differences between contexts. |

| del Pino et al.[49], the USA | To understand unhealthy alcohol use behaviours in socially disadvantaged, middle-aged and older Latino day labourers. | n = 14, Age = 50–64 years, Drinking status = occasional and frequent binge drinkers. | Semi-structured interviews, Grounded theory | Perceived consequences of unhealthy alcohol use on physical and mental health; The impact of unhealthy alcohol use on family relationships; The family as a key factor in efforts to change behaviour | Lack of transparency in reporting; thick description in places within context of individual characteristics, but no trends presented. |

| Edgar et al.[50], the UK |

|

n = 40, Age = 55–81 years, Drinking status = current or non-drinkers. | Semi-structured interviews, Thematic analysis | Routes into retirement; drinking routines; ‘keeping busy’: work and leisure in retirement; adapting to changing social networks; processes offering protection: adapting drinking routines | Inconsistent transparency in reporting; thick description of findings presented, supported by contextual detail with trends conveyed. |

| Gell et al.[51], the UK |

|

n = 19, Age = 59–80 years, Drinking status = abstainers, low-level drinkers, mid-level drinkers or high-level drinkers. | Semi-structured interviews, Thematic and framework analysis | Current alcohol consumption among interview participants; Changes in alcohol consumption among interview participants; Psychological capability; Reflective motivation; Automatic motivation; Physical opportunity; Social opportunity | Thick description of findings; quotes at times appeared to be used out of original context to support the points made. |

| Haarni and Hautamaki [52], Finland | To analyse the relationship third-age people have with alcohol: how does long life experience affect drinking habits and what are those habits actually like in the everyday life of older adults? | n = 31, Age = 60–75 years, Drinking status = current- or ex-consumers of alcohol. | Biographical and semi-structured interviews, Content and biographical analysis | Different kinds of drinking career; The ideal of moderation; Ageing, generation and period of time | Study limitations were not considered in reporting; thick description of study findings with contextual detail provided; quotes at times appeared to be used out of original context to support the points made. |

| Johannessen et al.[64], Norway | To investigate older peoples’ experiences with and reflections on the use and misuse of alcohol and psychotropic drugs among older people | n = 16, Age = 65–92 years, Drinking status = experience with drinking but no known history of misuse. | Narrative interviews, Phenomenological-hermeneutic analysis | To be a part of a culture in change; To explain use and misuse | Potential biases of research team were not explored; thin description of study findings with no discussion of sample characteristics or trends in the data. |

| Joseph [54], Canada | To examine the alcohol-infused leisure practices of a group of older Afro-Caribbean men in Canada and the ways alcohol consumption at cricket grounds plays an integral role in the reproduction of club members’ gender as well as their homeland cultures, age, class and national identities | n = not reported due to study design, Age = 44–74 years, Drinking status = leisurely drinkers. | Observations and interviews, Inductive analysis | Drunkenness as a mask of physical degeneration; Drunkenness as temporal escape from femininity and family; Alcohol brands as class and (trans)nationality markers | Insufficient reporting of study limitations; thick description of study findings presented with rich contextual detail. |

| Kim [55], Canada | To explore the drinking behaviour of older Korean immigrants | n = 19, Age = 62–83 years, Drinking status = mostly (63%) drank more than once a week. | Semi-structured focus groups, Thematic analysis | Reasons for drinking among men versus women; Health and alcohol; Signs of problem drinking; drinking in immigrant life; Reasons for a change in drinking behaviour; Religion | Potential biases of research team were not explored; thick description of study findings with trends explored and rich contextual detail provided. |

| Reczek et al.[65], the USA | To provide insight into the processes that underlie the alcohol trajectories of mid- to later-life men’s and women’s heavy alcohol use identified in the quantitative results | n = 88, Age = 40–89 years, Drinking status = self-reported heavy alcohol users. | In-depth interviews, Inductive analysis | The gendered context of (re)marriage; The gendered context of divorce | Inconsistent transparency in reporting; potential biases of research team were not explored; thick description of study findings presented with rich contextual detail and exploration of trends. |

| Sharp [56], the USA | To understand the communication between community-based older adults and their physicians regarding their alcohol use | n = 11, Age = 79 years (mean), Drinking status = frequent drinkers. | Semi-structured interviews, Interpretive phenomenological analysis | Factors that hinder alcohol conversations; Characteristics that promote positive patient-doctor relationships | Unclear whether the sample was appropriate for the purpose of the study as most participants had never discussed alcohol use with their physician; thin description of study findings with no supporting excerpts or exploration of trends. |

| Stanojevic-Jerkovic et al.[70], Slovenia | To describe drinking patterns in older people, to identify the most common risk factors and protective factors for hazardous or harmful drinking, older people’s empowerment for resisting social pressure to drink and their knowledge about low risk drinking limits | n = 20, Age = 63–89 years, Drinking status = current drinkers, abstainers or occasional drinkers. | Focus groups, Thematic analysis | Factors that stimulate drinking; Factors hindering drinking; Factors that for some people encourage drinking, for others hinder it; Behaviour in a drinking company; Seeking for help; Familiarity with the recommendations for low-risk drinking; Further findings | Potential biases of research team were not explored; thick description of study findings with rich contextual detail and some exploration of trends. |

| Tolvanen [72], Finland | To examine the ways in which older people in Finland talk about their use of alcohol. It also aims to shed light on the meaning of alcohol use in the context of social ageing | n = 40, Age = 60–89 years, Drinking status: not reported. | Structured interviews, Discourse and conversation analysis | Alcohol use as discussed by older people; Who is the ‘one’ who drinks? | Insufficient transparency in reporting; questionable suitability of data for qualitative analysis; thick description of findings with contextual trends presented. |

| Tolvanen and Jylha [62], Finland | To explore how alcohol use was constructed in life story interviews with people aged 90 or over | n = 181, Age = 90+ years, Drinking status = abstainers and current drinkers. | Semi-structured/life story interviews, Discourse analysis | I and others: The use of alcohol as a moral issue; Men’s and women’s drinking; Alcohol as a man’s destiny and a threat to the happiness of homes; Alcohol use as part of social interaction; Alcohol use as a health issue | Inconsistent transparency in reporting; limitations and potential biases of research team were not explored; thick description of findings in places with trends presented; limited discussion of findings in relation to participant characteristics. |

| Vaz De Almeida et al.[63], Europe (Denmark, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK) | To explore social and cultural aspects of alcohol consumption in a sample of older people living in their own homes, in eight different European countries | n = 644, Age = 65–74 years, Drinking status = non-dependent. | Semi-structured interviews, Grounded theory | Alcohol consumption narratives of older people; Gender differences in the narratives; Specific cultural differences between the eight countries | Inconsistent transparency in reporting; reported methods of analysis did not appear compatible with data collected; thinner description of data with some exploration of trends but descriptive themes; quotes lacked depth where presented. |

| Ward et al.[57], the UK | To generate a wider evidence base by exploring the circumstances in which older people drink, the meaning that drinking alcohol has for them and its impact, acknowledging that this can be a pleasurable and positive experience, as well as something that can have adverse health, financial, personal and interpersonal impacts | n = 21, Age = mid 50 s to late 80 s (years), Drinking status = regular drinkers who may or may not have a problem with their level of alcohol consumption. | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups, Thematic analysis | Drinking practices and styles; What affects drinking styles; Seeking help | Inconsistent transparency in reporting; insufficient exploration of limitations and biases; thick description of findings with some trends presented. |

| Watling and Armstrong [58], Australia and Sweden | To identify attitudes that might influence drink-driving tendency among this group of women and further show how these attitudes vary across countries | n = 30, Age = 52 years (mean), Drinking status = low-risk or risky drinkers. | Semi-structured interviews, Thematic analysis | Findings were not organised under theme headings | Potential biases of research team were not explored; thinner description of findings with inconsistent provision of contextual data. |

| Wilson et al.[71] (a), Haighton et al.[69] (b), Haighton et al.[68] (c), the UK |

|

n = 51, Age = 51–95, Drinking status = abstainers, occasional drinkers, moderate drinkers, heavy drinkers, recovering dependent drinkers and dependent drinkers. | In-depth interviews and semi-structured focus groups, Grounded theory and discursive analysis |

|

|

Data synthesis

A thematic synthesis of included studies was conducted (see Figure A1 in Appendix 1, available at Age and Ageing online). The methods for synthesis were based upon Braun and Clarke’s principles of thematic analysis, commonly applied to primary qualitative data [45]. The review team familiarised themselves with the findings of each study during full text screening and immersion through repeated reading. During this phase, the lead author listed ideas and potential codes from the primary study findings. The compiled codes were comparable to second- and third-order constructs described in meta-ethnography. Second-order constructs are interpretations and themes derived from the primary data, specified by the authors of included studies. Third-order constructs are ideas and interpretations identified by the review team which further explain findings within and across the primary studies [46]. Recurring codes, explaining findings across the studies, were developed by the review team into a candidate framework of themes which explained the views of older people surrounding their drinking. NVivo (version 11) was used for data management, which involved storing included study findings, and coding these according to the developed framework. The lead reviewer recorded analytical notes during this process, detailing explanations and patterns within each theme. The developed thematic framework was then further refined to ensure that it reflected the views and experiences conveyed across the included studies, and defined to form the theme descriptions which are presented as our findings. Excerpts from the included studies were identified to present as examples of the review findings. Throughout this process, developing themes were discussed amongst the research team and Gusfield’s sociological work on drinking rituals [47] informed data interpretations.

Results

Literature search and study descriptions

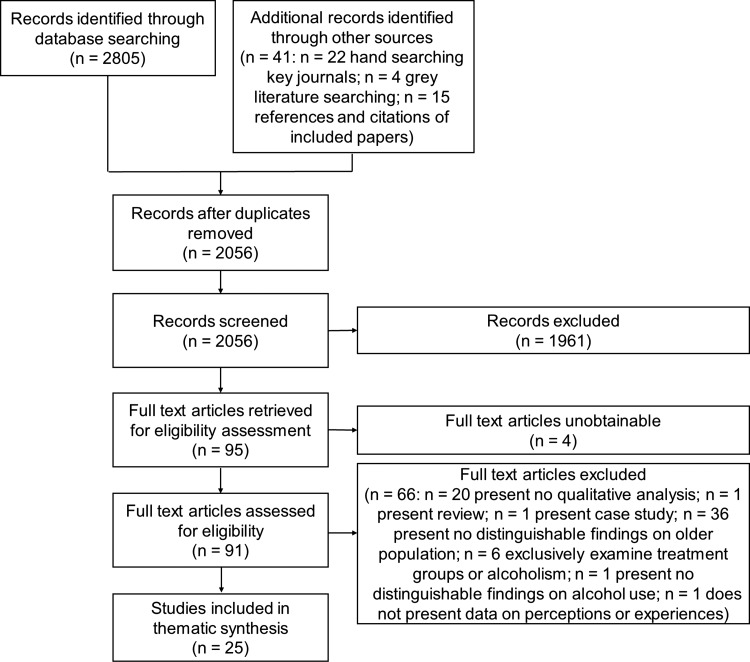

Twenty-five papers, reporting 21 unique studies were included (see Figure 1). The synthesis of findings involved over 1,500 older adults, aged 50–90 years upwards (see Table 1 for summary of study details). Most studies included men and women. One study had all female participants [48]. Authors variably reported other characteristics including socioeconomic status (four studies) [49–52], ethnicity (seven studies) [49, 53–58], health status (four studies) [49, 51, 52, 59], work status (four studies) [49, 52, 54, 60], living context (seven studies) [52, 53, 57, 59, 61–63], marital status (eight studies) [52, 53, 55–58, 64, 65], religion (one study) [55] and sexuality (one study) [57] (detailed in Table 3 Appendix 1, available at Age and Ageing online where reported). All studies included participants with a range of drinking behaviours including abstainers (10 studies) [50–52, 62, 66–71], occasional drinkers (six studies) [48, 51, 67–69, 71], moderate drinkers (20 studies) [48, 50–53, 55–59, 61, 62, 64, 66–71] and heavy drinkers (10 studies) [49, 51, 54, 58, 59, 65, 67–69, 71]. Five studies included some people who may have been dependent on alcohol, but these were a minority of participants [49, 65, 68, 69, 71]. Studies were from 16 countries. Six studies were conducted in the UK [50, 51, 57, 68, 69, 71], four in the USA [49, 53, 56, 65], Finland [52, 62, 66, 72] and Sweden [48, 58, 60, 66], two in Canada [54, 55] and Australia [58, 61]. Single studies included participants from New Zealand [59], Russia [67], Norway [64] and Slovenia [70]. Three studies were conducted across several European countries [63, 64, 66]. Three studies specifically focussed on settled migrant groups [49, 54, 55]. Where reported, most samples were recruited either purposively (six studies) [50, 51, 61, 68, 69, 71] or opportunistically (10 studies) [49, 52, 55–58, 60, 65, 67]. Ten studies also employed snowball sampling [49, 60, 52, 55, 56, 58, 60, 68, 69, 71]. Data were collected through in-depth/semi-structured interviews, focus groups, written autobiographical responses and ethnographic observation. A range of theories and approaches were applied to qualitative analyses, including grounded theory, discourse analysis, conversation analysis and thematic analysis. The main quality limitations related to a lack of transparency in reporting and triangulation or exploration of potential biases.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram depicting the flow and number of studies identified and then excluded at each stage during identification of papers for inclusion in this review.

Themes

Supporting quotes are presented in Table 2. The sex and age of participants are provided where available.

Table 2.

Supporting quotes for the key themes presented

| Theme: | Supporting quotes: |

|---|---|

| (1) Routines and rituals |

|

| (2) Self-image as a responsible drinker |

|

| (3) Alcohol and the ageing body |

|

| (4) Access to alcohol |

|

Routines and rituals

Across their life-course, older adults reported developing specific routines related to their drinking as leisure practices. Descriptions of their drinking were bound to certain contexts [48, 50–57, 59–72], such as with meals or in company. Some drinking seemed to hold additional symbolic meaning and was more ‘ritualistic’ as opposed to just regular or repeated (routinised) activity. Thus, whilst drinking was engrained within many social occasions [48, 50–55, 57, 59–63, 66–68, 70–72], it could also become a meaningful part of spending time with friends and family members [50–53, 56, 57, 59, 60, 63, 65, 66, 71, 72]. Drinking routines helped older people ‘stay in touch’ in their relationships (for example, quote 1i) [48, 50–55, 57, 59–62, 66, 67, 69, 71, 72]. For some, the social role of alcohol increased due to the effect of transitions such as retirement or bereavement in later life, which could lead to an increased frequency of drinking occasions [50, 57, 60, 61, 69]. Some heavier drinkers felt it would be difficult to spend time with friends or family without alcohol [51, 55, 69], although situations were also described where a change in drinking habits could adversely affect their social opportunities (quote 1ii).

Drinking was seen as supporting relaxation during spare time (for example, quote 1iii) [51–53, 57, 59–61, 63, 67, 69, 71] which was generally viewed as more plentiful following retirement. This increase in spare time sometimes led to an increase in the number of contexts and activities where alcohol was consumed (quote 1iv) [50, 57, 60, 61, 69]. Drinking could act to maintain structure in older people’s lives, which may have been lost in retirement, symbolising distinct leisure time and creating a clear daily routine [50, 61, 67]. For a small number, the loss of external structure associated with retirement and children leaving home could lead to heavier drinking [50].

Routines and/or rituals in older adults’ drinking practices were shaped by social norms and expectations [48–55, 57–61, 63–67, 69–72]. For example, the central role of alcohol was highlighted in retirement communities, where social occasions were based in drinking settings [53, 61]. Most older adults reported that they had reduced their previous overall intake of alcohol with age [48, 51, 52, 59, 63]. However, risky or unhealthy patterns of drinking were described as normal for older adults in some cultures, such as Mexican, Caribbean, Nordic and Russian cultures, particularly amongst men [49, 54, 63, 67]. Women more often described increasing their drinking in later life from previously lower levels [50, 52, 63, 69]. Whilst gender differences in norms and expectation of drinking were present, some described more equal expectations, suggesting these differences were reducing (quote 1v). Scandinavian and Finnish participants described how their lower levels of drinking were shaped by historic temperance movements [52, 62, 64, 66, 72], particularly amongst women, who were expected to drink less than men. Cultural norms also altered the drinking habits of migrants, where older adults report integrating the new culture with that of their home country [54, 55]. This served either to restrict previously risky drinking habits, or encourage riskier practices in groups whose home country consumed less alcohol.

Self-image as a responsible drinker

Most older adults saw themselves as controlled, responsible and considered in their drinking behaviour (quote 2i) [48, 50–53, 55–60, 62, 66, 68, 71, 72]. This represented their perception of what the image of an older drinker should be, for example quote 2ii. Their experience with drinking across the life course was perceived to make them wiser about drinking [48, 50–52, 59, 60, 64, 66, 70, 71]. Older people presented an idealised view of moderate, low-risk styles of drinking [48, 50–53, 55–57, 59–68, 71, 72]. Idealisation of abstinence or low-level drinking was more likely amongst the oldest individuals, particularly in Scandinavian countries [48, 50, 62, 63].

Drinking was described around these ideals, and justifications of drinking emphasised positive experiences with alcohol [48, 50–52, 54, 55, 57, 60–63, 66–68, 71]. Many participants described their drinking as appropriate to the context [48, 50–55, 57–63, 65–68, 71, 72], and usually aligned to their companions [48, 51–53, 56, 57, 59–63, 65, 70–72]. Social context could sometimes justify drinking to excess [48, 50–53, 57, 59–62, 65, 67, 70, 71]. Whilst alignment of drinking with social peers usually restricted drinking, it could also increase consumption in the company of heavy-drinking friends [52, 56, 60, 61, 65, 67, 70, 72]. A failure to align with companions’ drinking could cause relationship problems—particularly with partners or family, but also within wider social groups [49, 50, 57, 65, 66, 69, 70]. Those with more problematic alcohol use consequently reported drinking more heavily in private, to conceal their higher consumption (quote 2iii) [51, 56, 57, 61, 69].

Drinking was seen to be acceptable, provided day-to-day responsibilities remained fulfilled. Many personal responsibilities judged to be incompatible with drinking were lost in later life, through retirement [50, 52, 57, 60, 61] or reduced parental responsibilities [51, 54, 57, 60, 66]. These changes enabled increased alcohol consumption (quote 2iv). However, some older adults acquired new responsibilities during retirement which restricted drinking, including voluntary work, or caring for a sick partner [50, 51, 60, 69]. Conversely, drinking could act as a form of escapism from responsibilities as demonstrated in Joseph’s Caribbean-Canadian cricketer community, where family responsibilities were passed on to partners, as drunkenness ensued [54].

Controlled and responsible drinking was often maintained through self-imposed limits or rules (for example, quote 2v) [51–53, 55, 56, 58–63, 66–68, 70, 71]. Heavier drinkers also applied rules and limits to restrict their drinking (quote 2vi). These self-made restrictions played a large part in exerting control and reducing alcohol consumption in later life. Drinking habits in later life were also shaped by stigmatisation of certain drinking styles [48, 50, 52, 54, 55, 57–63, 66–68, 70–72]. Inappropriate drunkenness, alcoholism, drinking alone, drink-driving and women’s drinking were all judged to be unacceptable. Older adults avoided identifying with these behaviours [48, 50, 52, 54, 55, 57–63, 66–68, 70–72].

There was a general perception that ‘problematic’ and ‘normal’ drinking behaviours were separate entities [51, 59, 60, 63, 71]. Problematic drinking was associated with a lack of control, need, and risk [51, 52, 59, 60, 71]. Most older adults identified themselves as ‘normal’ drinkers, framing their consumption as responsible and acceptable compared with problematic use [50, 57–60, 62, 63, 71, 72]. However, this perception meant that many did not reflect upon the increased risks attached to drinking as an older person. Those recognising issues with their drinking did so through identification with the problematic drinking discourse [49, 51, 52, 60, 65, 68, 71].

Alcohol and the ageing body

Older people recognised the positive and negative effects that alcohol could have on their bodies as they aged [48–57, 59–72]. Alcohol was valued for its ability to create feelings of pleasure [50, 52, 53, 57, 59–61, 63, 66, 67, 69, 71] and relaxation [50–53, 57, 59–61, 66, 67, 69, 71], which were perceived as an important part of enjoying later life. Alcohol was also believed to have positive effects for health and well-being in older age [49–51, 53–55, 57, 59, 61, 63, 66, 67]. Many viewed alcohol as protective to health [56, 59], particularly when taken in moderation [55, 59, 62]. This led some to believe that not drinking could be negative for health (quote 3i). The health benefits of red wine and whiskey were emphasised [51, 55, 57, 59, 61, 63, 66, 69], but this appeared to be a means of justifying preferences, rather than encouraging a change in use (quote 3ii). The perceived positive effects of drinking led many to view alcohol as a form of medicine [48–51, 53–55, 57, 59, 62–64, 66, 67, 70, 72], particularly in Scandinavian countries. Reported medicinal uses were wide ranging. Aside from preventing numerous diseases, alcohol was seen to cure many physical ailments such as digestive problems, colds and pain (for example, quote 3iii) [48, 51, 54, 55, 62–64, 66–68, 70, 71]. At times, alcohol was used in place of medications [50, 51, 68], as a sleeping aid [51–53, 55, 57, 59, 63, 66, 68, 72], or to promote mental health [48–53, 55, 57, 59, 61, 66–68]; particularly amongst women. Alcohol use could, however, become heavy when relied upon to cope with stressors or mental illness in later life (quote 3iv) [48, 51, 52, 57, 65]. Some recognised that using alcohol in this way could negatively impact mental health [49, 51, 57, 59, 68, 71].

Other negative effects of alcohol were recognised [48, 50, 51, 53, 59, 62, 63, 66, 69, 71, 72]. Older adults were especially aware of short-term consequences associated with intoxication, such as hangovers, accidents and blackouts [48–50, 52, 59, 63, 68, 69, 71]. Longer-term damage was recognised as a potential consequence of drinking [49–51, 54, 57, 59, 62, 69, 71], usually associated with heavier intake. Authors noted that these negative consequences were usually discussed by older adults after prompting, rather than spontaneously described [59, 71]. Many older people were aware of the dangers of drinking whilst taking medication [48, 50, 51, 56, 57, 59, 63, 64, 68, 71, 72]. However some participants, particularly heavier drinkers, described drinking alongside or with medications [51, 59, 64, 68].

In later life, most participants reflected that health was a major priority [51, 59]. The ageing body was felt to be more fragile, requiring greater care than before. Some saw the ability to drink in later life as a sign of good health and resilience [54, 55]. Many adjusted their drinking because of the perceived effects of alcohol on health [50–52, 57, 59, 62–64, 68–72]—particularly men, who had often consumed at higher levels earlier in life [51, 55, 68]. A small number described maintaining their alcohol intake, despite concerns for their health [48–51, 54, 57, 68–71]. Heavier drinkers continued to drink heavily as they saw intoxication to be one of life’s remaining pleasures (quote 3v) [55, 57, 69]. Some looked for other explanations for their problems, justifying continued drinking (quote 3vi). Whether alcohol use was reconsidered in later life was determined by the salience of health issues [49–51, 57, 59, 64, 71]. Experiencing negative impact of alcohol on health, either directly or through others’ experiences, led to changes in alcohol use. Others justified their heavier drinking habits through the lack of noticeable effect on their health (quotes 3vii).

Access to alcohol

Financial and environmental factors were strong influences on access to alcohol, and how much was consumed [50–53, 55, 57–61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, 72]. The accessibility of shops and drinking establishments shaped levels of drinking [51–53, 57, 61, 69, 72]. Mobility issues could complicate access to alcohol [51, 57, 69, 72]. However, drinking could also be facilitated through visits from heavy-drinking friends [57, 69]. In retirement villages, the availability of alcohol in social areas increased residents’ drinking [53, 61]. Those living in residential care homes with restrictive alcohol policies could have drinking curtailed [70, 72].

Drink-driving legislation was a major consideration, constraining many older people’s drinking (quote 4i) [50–53, 55, 57–59, 61, 63]. Restrictions on drink-driving had most impact on socioeconomically advantaged groups, who tended to drink in friends’ homes [51]. For individuals living in suburban areas, a lack of public transport could enforce the need to drive [55]. However, in urban settings, safety became a key consideration, restricting time spent drinking outside the home [51].

Financial considerations also shaped older people’s drinking [53, 60, 63, 66, 67, 70]. Those with higher disposable incomes increased spending on alcohol and vice-versa [54, 57, 63, 67, 72], although some binged when money was available (quote 4ii). Heavier drinkers prioritised spending on alcohol regardless of income, adjusting their drinking style to fit with the money available [50, 54, 57].

Discussion

Our review described the multifaceted role of alcohol in older adults’ lives. Drinking could help sustain social and leisure activity, which may otherwise diminish through retirement and other transitions relating to the ageing process [16, 20]. The positive and valuable roles of alcohol seen here in older people’s lives contrast with the majority of studies of older people’s drinking, which focus on risks to health and alcohol use as a coping mechanism for the challenges of ageing [16, 73, 74].

Our review also identified some negative implications of alcohol consumption for older people. Health may be adversely affected if well-established heavy-drinking habits are maintained into later life, or conversely, social lives may diminish if drinking is affected by health concerns. Alcohol consumption alongside health conditions and medication use also carries some risks [9]. Older people may need advice and support to recognise and address potentially adverse interactions [16, 74]. The link between older adults’ drinking and loneliness is another common negative view of drinking in later life [16, 73, 76] although no studies within this review directly addressed this issue. This may reflect a sense of stigma associated with isolation and loneliness, or the tendency to recruit from social groups.

Older people typically viewed alcohol risks and harm as belonging to other heavier, more problematic drinkers. This process reflects the sociological concept of ‘othering’, where the positive, ‘healthy’ self-identity is protected through contrast with those worse off. ‘Othering’ may result in a barrier to change for those not recognising alcohol-related risk [77, 78]. People in good health did not consider the risks of their own drinking, as adverse outcomes may have been less salient compared with those in ill health. This is explained within biographical disruption theory, where good health is assumed unless it is disrupted through the experience of illness [74]. The perception of alcohol as a medicine for minor ailments was prominent in this review. In younger age groups, this is attached to problematic drinking [80–82], but amongst older people it cuts across all levels of consumption.

Social patterns of alcohol consumption reflect cultural trends in population drinking [83]. This suggests that reduced drinking in later life may be a product of cohort or period effects rather than a result of ageing [84]. Riskier drinking styles were demonstrated amongst some settled migrant groups through integration of drinking habits from the old and new countries [85]. However, maintenance of distinct drinking behaviours could also be a way of holding onto cultural or earlier life identity which could carry through into retirement communities [30, 86]. Gendered patterns are complicated and whilst gender differences are highlighted in certain cultures and often associated with men [10, 87], these differences may have decreased over time as women’s drinking becomes normalised. Men were more likely to report reductions in their drinking, whilst some women reported increased consumption in later life [88]. Particular patterns of risky drinking, such as drinking to self-medicate, were more commonly amongst women. Future exploration of the evolution of gender differences in alcohol consumption will be important.

This study is novel and applied a rigorous approach to systematic review methodology. Dual-screening and translation of foreign language material ensure that the findings represent literature currently available in the area. By drawing on qualitative literature, it has been possible to present a deeper insight into the reasons behind and social patterns of older people’s drinking than can be gleaned from other types of evidence. Our work drew on multiple qualitative studies and looked across different settings. The findings should be applicable beyond individual study populations, and provide a breadth of understanding of older people’s drinking. The inclusion of studies of populations from a range of different countries and social circumstances enabled social patterns to be identified. Our focus on non-treatment groups meant findings are relevant to the majority of the older population—a valuable contribution to our understanding of older people’s drinking.

A number of limitations must be acknowledged in interpreting our findings. Qualitative data are based upon participants’ responses, and so may convey any inaccuracies associated with recall and possibly socially desirable accounts as alcohol use can be a sensitive issue [89]. Good methodology such as rapport building, probing and authenticity checking can reduce this risk [86]. However, in synthesising findings, we are reliant on the reporting of authors of included studies, and some described their analytical approach better than others. Nevertheless, the patterns we have presented are generally reflected in quantitative studies of older people’s drinking [10, 20]. The sampling strategies employed in included studies may also have narrowed the socio-demographic characteristics represented within our findings. Pooling of cross-cultural data may mean that country-specific drinking norms receive less emphasis in our findings. However, this loss of specificity needs to be balanced against a wide and culturally diverse literature which included both settled and migrant communities across most of the developed world.

In conclusion, our findings emphasise that drinking routines can become firmly established in older people’s lives across the life-course. Modifying older people’s drinking is likely to be a challenge, as well-established patterns of behaviour can be hard to change. However, some older people may reconsider their drinking when concerned about their health in later life. Consequently, routine health checks or other clinical contacts may represent teachable moments in clinical practice, where older people may be receptive to reconsidering their drinking behaviour when this is relevant to their health. Available data on alcohol consumption suggests that positive engagement with the large section of the older population who consider themselves to be controlled and responsible drinkers may be a more effective approach to prevention than focussing on high risk individuals [16]. In any future interventions, it will also be important to acknowledge the positive role of alcohol in the social lives of older people. New social and leisure opportunities may be needed, to replace those associated with heavy or risky drinking. Furthermore, effective interventions will need to act at individual, social, cultural, and environmental levels since all play a key role in shaping and sustaining later life drinking.

Key points.

Alcohol presents risks to older people’s health, but also plays important roles in their lives.

Alcohol use is routinised in older people’s lives, and can be an important part of social occasions.

Most older people consider themselves to be responsible drinkers, making them less likely to recognise risks in their drinking.

Public health interventions to modify older people’s drinking should consider targeting older adults identifying as responsible drinkers.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This research is funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR). The views are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the National Health Service or the Department of Health. The SPCR played no part in the conduct of this review.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Note: The very long list of references supporting this article has meant that only the most important are listed here. The full list of references is available in the Supplementary data.

- 1. Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet 2005; 365: 519–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lea W. Department of Health. Alcohol Guidelines Review–Report from the Guidelines development group to the UK Chief Medical Officers. London: Crown copyright, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilkinson C, Dare J. Shades of grey: the need for a multi-disciplinary approach to research investigating alcohol and ageing. J Public Health Res 2014; 3: 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu L-T, Blazer DG. Substance use disorders and psychiatric comorbidity in mid and later life: a review. Int Epidemiol 2014; 43: 304–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dar K. Alcohol use disorders in elderly people: fact or fiction? Adv Psychiatr Treat 2006; 12: 173–81. [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Connell H, Chin AV, Cunningham C, Lawlor B. Alcohol use disorders in elderly people—redefining an age old problem in old age. BMJ 2003; 327: 664–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blow FC, Barry KL. Alcohol and substance misuse in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2012; 14: 310–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klein WC, Jess C. One last pleasure? Alcohol use among elderly people in nursing homes. Health Soc Work 2002; 27: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pringle KE, Ahern FM, Heller DA, Gold CH, Brown TV. Potential for alcohol and prescription drug interactions in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 1930–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Towers A, Sheridan J, Newcombe D. The drinking patterns of older New Zealanders: National and international comparisons. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hodges I, Maskill C. Alcohol and older adults in New Zealand. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Knott CS, Scholes S, Shelton NJ. Could more than three million older people in England be at risk of alcohol-related harm? A cross-sectional analysis of proposed age-specific drinking limits. Age Ageing 2013; 42: 598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Office for National Statistics Adult drinking habits in Great Britain: 2005–2016. Newport: Office for National Statistics, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hallgren M, Hogberg P, Andreasson S. Alcohol consumption among elderly European Union citizens: health effects, consumption trends and related issues. Östersund: Swedish National Institute of Public Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holley-Moore G, Beach B. Drink wise, age well: alcohol use and the over 50s in the UK. UK: International Longevity Centre, 2016; 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moos RH, Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos BS. Older adults’ health and late-life drinking patterns: a 20-year perspective. Aging Ment Health 2010; 14: 33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wadd S, Papadopoulos C. Drinking behaviour and alcohol-related harm amongst older adults: analysis of existing UK datasets. BMC Res Notes 2014; 7: 741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division World population ageing. New York: United Nations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holdsworth C, Frisher M, Mendonça M et al. . Lifecourse transitions, gender and drinking in later life. Ageing Soc 2017; 37: 462–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sacco P. Understanding alcohol consumption patterns among older adults: continuity and change In: Kuerbis A, Moore A, Sacco P, Zanjani F, eds. Alcohol and Aging: Clinical and Public Health Perspectives. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wadd S, Holley-Moour G, Riaz A, Jones R. Calling time: addressing ageism and age discriminationin alcohol policy, practice and research. United Kingdom: Drink Wise Age Well, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gell L, Meier PS, Goyder E. Alcohol consumption among the over 50s: international comparisons. Alcohol Alcohol 2015; 50: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rao R, Schofield P, Ashworth M. Alcohol use, socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity in older people. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e007525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stevenson BS, Stephens C, Dulin P, Kostic M, Alpass F. Alcohol consumption among older adults in Aotearoa/New Zealand: a comparison of ‘baby boomers’ and ‘over-65s’. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine 2015; 3: 366–78. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rao T. Alcohol and dementia: Adding insult to injury? Alcohol Policy UK 2015. [cited 2015 18/12].

- 27. Social Issues Research Centre Social and cultural aspects of drinking. Oxford: Social Issues Research Centre, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Najjar LZ, Young CM, Leasure L, Henderson CE, Neighbors C. Religious perceptions of alcohol consumption and drinking behaviours among religious and non-religious groups. Ment Health Religion Cult 2016; 19: 1028–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sudhinaraset M, Wigglesworth C, Takeuchi DT. Social and cultural contexts of alcohol use: influences in a social–ecological framework. Alcohol Res 2016; 38: 35–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alexander F, Duff RW. Social interaction and alcohol use in retirement communities. Gerontologist 1988; 28: 632–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.