Abstract

Objective

to investigate the impact of the availability and supply of social care on healthcare utilisation (HCU) by older adults in high income countries.

Design

systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

medline, EMBASE, Scopus, Health Management Information Consortium, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, NIHR Health Technology Assessment, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, SCIE Online and ASSIA. Searches were carried out October 2016 (updated April 2017 and May 2018). (PROSPERO CRD42016050772).

Study selection

observational studies from high income countries, published after 2000 examining the relationship between the availability of social care (support at home or in care homes with or without nursing) and healthcare utilisation by adults >60 years. Studies were quality assessed.

Results

twelve studies were included from 11,757 citations; ten were eligible for meta-analysis. Most studies (7/12) were from the UK. All reported analysis of administrative data. Seven studies were rated good in quality, one fair and four poor. Higher social care expenditure and greater availability of nursing and residential care were associated with fewer hospital readmissions, fewer delayed discharges, reduced length of stay and expenditure on secondary healthcare services. The overall direction of evidence was consistent, but effect sizes could not be confidently quantified. Little evidence examined the influence of home-based social care, and no data was found on primary care use.

Conclusions

adequate availability of social care has the potential to reduce demand on secondary health services. At a time of financial stringencies, this is an important message for policy-makers.

Keywords: access, healthcare, older people, social care, systematic review

Background

As people age, they are increasingly likely to live with multiple conditions and require support from a range of different health and social care services. In most high income countries, welfare systems are attempting to meet rising demands from an ageing population with constrained funding [1–4]. The number of older people requiring support is expected to rise significantly to 2050 [5]. The organisation of long-term and social care varies within and between countries, but how best to meet rising demands and fund equitable care, are common concerns [6].

Social care describes services that provide support for adults with physical or mental illness or disability [7]. This is care that supports an individuals’ day to day needs including help with activities of daily living, typically in their own home or in care homes (with or without nursing) [8]. In recent years, the social care sector has experienced decreasing profits, a slow growth in care home beds and loss of services from the market [9, 10]. In England and Wales, for example, per capita funding for social care decreased by an average of 1.6% (England) and 0.4% (Wales) per year between 2008/9 and 2014/15 [11]. Reduction in funding and market supply exacerbate the potential for inequitable access to care [9, 12] Means testing of state funded care further restricts access to people with the lowest incomes. With reduced state funding for social care, such means testing will likely support fewer individuals, forcing more to fund their own care, adding further barriers to access. Geographical variation in funding, provision and demand for social care are also evident within [13–17], and between [18, 19], countries. This is important because recent evidence has linked reductions in social care expenditure with increased mortality for those aged over 60 [20]. An estimated one million older adults in England have an unmet need for social care, with the very old and those living alone most affected. In the past, unpaid family care has compensated for a lack of formal care provision [21], but current estimates suggest that the number of older adults requiring care will soon exceed the number of family caregivers available [22]. Access to social care is, therefore, a critical issue. The sustainability of the care sector is in-question and there have been persistent calls for a longer-term solution [23, 24].

Deficiencies in social care have been linked to pressures on the health sector, both in the UK and other high income countries [6, 16]. Delayed discharge of patients from hospital is often cited as one such outcome of poor access to social care. Evidence of a direct relationship between social care resources and health service demands would provide a strong argument for ensuring that the funding of both is adequate. With increasing policy focus on these issues across the world, a review of evidence is both critical and overdue. The aim of this study is to systematically review evidence on the relationship between availability and supply of social care and healthcare utilisation (HCU) for older adults.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched for empirical research with older adults (the population) that measured access to social care (the exposure) and HCU (the outcome) (see supplementary material for example search strategy, available in Age and Ageing online). Searches were carried out in October 2016 in OVID Medline (1946-present), EMBASE (1974-present), Scopus, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) 1979–16 September, EBM Reviews: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, NIHR Health Technology Assessment, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, SCIE Online, and ASSIA. Searches were rerun in April 2017 to identify any further papers published in the period of undertaking the review. A final updated search was performed May 2018; no further eligible studies were identified. Reference lists of included studies and review articles were scrutinised, and table of contents of key journals were scanned to identify additional relevant articles.

Studies published after 2000 in any language were included if they were set in a high income country [25], focused on adults aged over 60 years, and examined the relationship between an indicator of social care accessibility and HCU. Social care accessibility was defined using the four domains described by Gulliford et al. (2002); [26] availability and supply, utilisation, equity and quality. This paper reports on a synthesis of the evidence on the availability and supply of social care [26]. These concepts were understood to refer to the opportunity to use services, and operationalised in this review as a measure of social care provision (e.g. number of care homes and/or care home beds, the number of homecare hours, and social care expenditure) relative to a measure of the potential client population (e.g. per 1,000 adults). Material published before 2000 was excluded because many countries have undergone service reorganisations in recent years, and there is often a long interval between data collection and study publication. Historic data was judged to be unlikely to offer a reliable reflection of contemporary experiences in health and social care. Studies were excluded if they presented information solely from existing users of social care without any comparison group or other data from the source population. The term ‘care home’ is used throughout this paper to refer to institutions with and without registered nurses on site. HCU refers to all contacts with, and use of primary and secondary healthcare services. Studies of experimental, quasi-experimental and observational design were eligible. Inclusion criteria were tested independently by two researchers on 10% of the records and minor revisions made before proceeding with study selection.

Study selection and synthesis

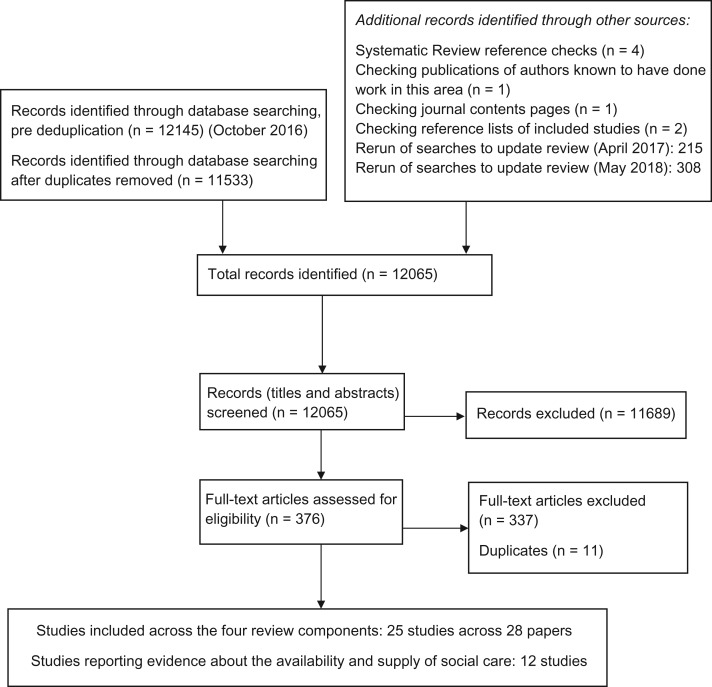

Titles and abstracts of all records were screened for potential relevance by the lead author, and 50% of records were examined by two researchers. An online software tool, Rayyan, was also used to manage and aid the screening process (https://rayyan.qcri.org/). Rayyan assists in identifying potentially relevant publications by learning from screeners’ previous decisions [27]. Full texts were then read and assessed for inclusion in the review (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2, available in Age and Ageing online). Study details and data were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet. Quantitative data were extracted from each paper as described in Supplementary Table 3, available in Age and Ageing online, where two (or more) studies included the same outcome and exposure, a random-effects meta-analysis summary estimate is provided for ease of discussion. No outcomes had sufficient number of studies for a formal meta-analytical approach.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection.

All studies were quality assessed using the National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [28]. The domains covered by this tool address all relevant aspects of bias for cross-sectional studies. Studies can achieve one of three overall ratings: good, fair and poor (Table 1 and supplementary appendix material, available in Age and Ageing online). The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42016050772).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Paper | Country | Study design | Years included | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bardsey 2010 [41] | UK | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2006–08 | Poor |

| Damiani 2009 [29] | Italy | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2004 | Poor |

| Fernandez 2008 [36] | UK | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 1998–2000 | Good |

| Forder 2009 [35] | UK | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2004–05 | Good |

| Gaughan 2013 [30] | UK | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2008–09 | Good |

| Gaughan 2015 [31, 40] | UK | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2009–13 | Good |

| Herrin 2015 [37] | US | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2007–10 | Good |

| Holmås 2014 [38] | Norway | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2007–09 | Fair |

| Hunold 2014 [39] | US | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2010 | Good |

| Imison 2012 [32] | UK | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2009–10 | Poor |

| Liotta 2012 [33] | Italy | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2006 | Poor |

| Reeves 2004 [34] | UK | Cross-sectional secondary analysis of administrative data | 2000 | Good |

Findings

Twelve studies were identified that met the review criteria, and reported evidence about the relationship between social care availability and supply and HCU (Figure 1) [29–41]. One study (across two publications) used overlapping data with the same methods, but only the more recent paper was included in the analysis [31, 40]. All studies used a cross-sectional design and presented analyses of administrative data (Table 2). Seven studies were carried out in the UK [30, 32, 34–36, 40, 41], two each in Italy [29, 33] and the USA [37, 39], and one in Norway [38]. The quality assessment rating was good for seven studies [30, 34–37, 39, 40] and one was rated fair [38]. Four studies were rated poor [29, 32, 33, 41], with three included in the synthesis after re-analysis [32, 33, 41]. Studies rated as good quality had considered various potential confounders and adjusted their analysis accordingly (see quality assessment in supplementary material, available in Age and Ageing online). These variables included measures of population characteristics, other care provision, area deprivation and wealth, indicators of need such as standardised mortality rates.

Table 2.

Key data for studies reporting evidence about the relationship between the availability and supply of social care and HCU outcomes

| Study | Year | Social care exposurea | Type of social care exposureb | Predictorc | Predictor definition | Outcomed | Type of admissionse | Outcome definition | Estimate | 95% CI Low | 95% CI High | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernandez | 2008 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Admissions | Emergency | % of discharges that become admissions | −1.373 | −2.244 | −0.502 | 0.444 |

| Herrin | 2015 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Admissions | Emergency | % of discharges that become admissions | −0.486 | −0.703 | −0.270 | 0.068 |

| Imison | 2012 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Admissions | Emergency | % of discharges that become admissions | 0.069 | −1.003 | 1.141 | 0.547 |

| Imison | 2012 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Length of stay | Emergency | Length of stay (days) | −0.063 | −0.678 | 0.551 | 0.314 |

| Gaughan Hip | 2013 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Length of stay | All | Length of stay (days) | −0.129 | −0.203 | −0.056 | 0.023 |

| Gaughan Stroke | 2013 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Length of stay | All | Length of stay (days) | −0.077 | −0.150 | −0.004 | 0.023 |

| Holmas | 2013 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per share % of 80+ | Length of stay | Emergency | Length of stay (days) | −0.002 | −0.012 | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| Holmas | 2013 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per share % of 80+ | Length of stay | All | Length of stay (days) | −0.003 | −0.008 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Holmas | 2013 | Care | Availability | Usage | Per % who are not discharged home | Length of stay | Emergency | Length of stay (days) | 1.713 | 1.622 | 1.804 | 0.046 |

| Imison | 2012 | Care | Availability | Usage | Per % who are not discharged home | Length of stay | Emergency | Length of stay (days) | 0.020 | −0.283 | 0.322 | 0.154 |

| Holmas | 2013 | Care | Availability | Usage | Per % who are not discharged home | Length of stay | All | Length of stay (days) | 1.283 | 1.221 | 1.346 | 0.032 |

| Fernandez | 2008 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Delayed discharge | Emergency | % of discharges that are delayed | −0.292 | −0.477 | −0.107 | 0.094 |

| Gaughan | 2015 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Delayed discharge | Emergency | % of discharges that are delayed | −0.578 | −1.048 | −0.108 | 0.240 |

| Gaughan | 2015 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Length of delay | Emergency | Length of delay (days) | −0.784 | −1.409 | −0.159 | 0.319 |

| Imison | 2012 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Length of delay | Emergency | Length of delay (days) | −1.595 | −4.856 | 1.667 | 1.664 |

| Hunould | 2014 | Care | Availability | Beds | Per 1% beds per population | Visits | Emergency | Visits to emergency departments | 0.830 | 0.304 | 1.356 | 0.269 |

| Fernandez | 2008 | Care | Spend | Spend | Per £1 spent | Admissions | Emergency | % of discharges that become admissions | −0.009 | −0.015 | −0.003 | 0.003 |

| Imison | 2012 | Care | Spend | Spend | Per £1 spent | Admissions | Emergency | % of discharges that become admissions | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.002 |

| Imison | 2012 | Care | Spend | Spend | Per £1 spent | Length of stay | Emergency | Length of stay (days) | −0.002 | −0.004 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Fernandez | 2008 | Care | Spend | Spend | Per £1 spent | Delayed discharge | Emergency | % of discharges that are delayed | −0.123 | −0.201 | −0.045 | 0.040 |

| Bardsley | 2010 | Care | Spend | Spend | Per £1 spent | Hospital spend | All | Hospital Spend £1 per year | −0.396 | −0.523 | −0.269 | 0.060 |

| Forder | 2009 | Care | Spend | Spend | Per £1 spent | Hospital spend | All | Hospital Spend £1 per year | −0.330 | −0.410 | −0.250 | 0.041 |

| Gaughan Hip | 2013 | Care | Cost | Cost | Per £1 cost | Length of stay | All | Length of stay (days) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Gaughan Stroke | 2013 | Care | Cost | Cost | Per £1 cost | Length of stay | All | Length of stay (days) | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Gaughan | 2015 | Care | Cost | Cost | Per 1% increase in price | Delayed discharge | Emergency | % of discharges that are delayed | 0.603 | −0.566 | 1.772 | 0.596 |

| Gaughan | 2015 | Care | Cost | Cost | Per 1% increase in price | Length of delay | Emergency | % of discharges that are delayed | 0.851 | 0.136 | 1.566 | 0.365 |

| Liotta | 2012 | Home | Availability | Percent | Per 1% increase in homecare | Admissions | All | % of hospital admissions | 0.846 | 0.020 | 1.672 | 0.390 |

| Fernandez | 2008 | Home | Availability | Hours | Per 1 h increase in homecare | Admissions | Emergency | % of discharges that become admissions | −0.800 | −2.313 | 0.713 | 0.772 |

| Holmas | 2013 | Home | Availability | Percent | Per 1% increase in homecare | Length of stay | Emergency | Length of stay (days) | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Holmas | 2013 | Home | Availability | Percent | Per 1% increase in homecare | Length of stay | All | Length of stay (days) | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Liotta | 2012 | Home | Availability | Percent | Per 1% increase in homecare | Length of stay | All | Length of stay (days) | 0.922 | 0.976 | 1.008 | 1.008 |

| Fernandez | 2008 | Home | Availability | Hours | Per 1 h increase in homecare | Delayed discharge | Emergency | % of discharges that are delayed | −0.050 | −0.166 | 0.066 | 0.059 |

aSocial care exposure: Impact of care home or impact of homecare.

bType of social care exposure: social care availability, costs or spend.

cPredictor: Summary type of predictor.

dOutcome: Summary description of the type of healthcare use outcome.

eType of admissions: type of admission accounting for healthcare use outcome.

Ten studies (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3, available in Age and Ageing online) were eligible for meta-analysis as they provided sufficient detail either from the analysis reported [35, 36, 38, 39], or from the data provided in the publication [32, 33, 41], or combining the analysis from the publication with summary statistics or external data referenced [30, 37, 40]. Two studies provided no analysis or data that could be combined [29, 34]. The reported HCU outcomes included delayed hospital discharge, length of hospital stay (LOS), readmissions to hospital, emergency service use, emergency bed use, emergency admissions and healthcare expenditure. No studies were identified that investigated access to primary care and which met our inclusion criteria. The synthesis is presented by HCU outcome.

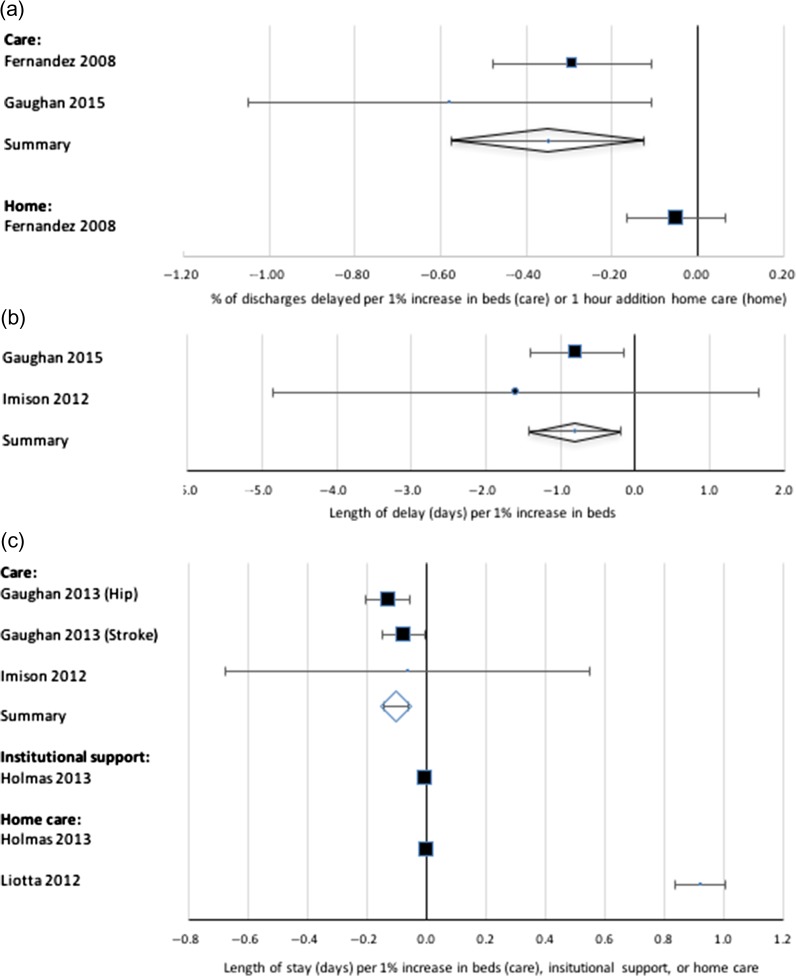

Delayed discharge

Three UK studies demonstrated that greater availability of care home beds was associated with reductions in rates of delayed discharges and the number of people experiencing delayed discharges (Figure 2a), and the number of days of delay (Figure 2b) [32, 36, 40]. There was no strong evidence to associate the availability of homecare with reductions in delayed discharges (Figure 2a, Supplementary Table 3, available in Age and Ageing online) [36]. Delayed discharges were also examined in relation to social care expenditure in two UK studies, with greater expenditure on social care found to be associated with reductions in delayed discharges in both (though one did not present data that could be combined) [34, 36].

Figure 2.

Influence of social care and homecare on delayed discharges and length of stay. (a) Impact of availability of beds on delayed discharge. (b) Impact of availability of beds on length of delay. (c) Impact of availability on length of stay.

Length of hospital stay

Length of hospital stay was available in four studies. Increase in availability of long-term care beds was associated with shorter LOS for the complete older population (Figure 2c), but not ‘institutional care’ [30, 32, 38]. Long-term care prices were not associated with LOS. The effect of homecare on LOS was inconsistent, but clearly much smaller in size [33, 38] (Figure 2c).

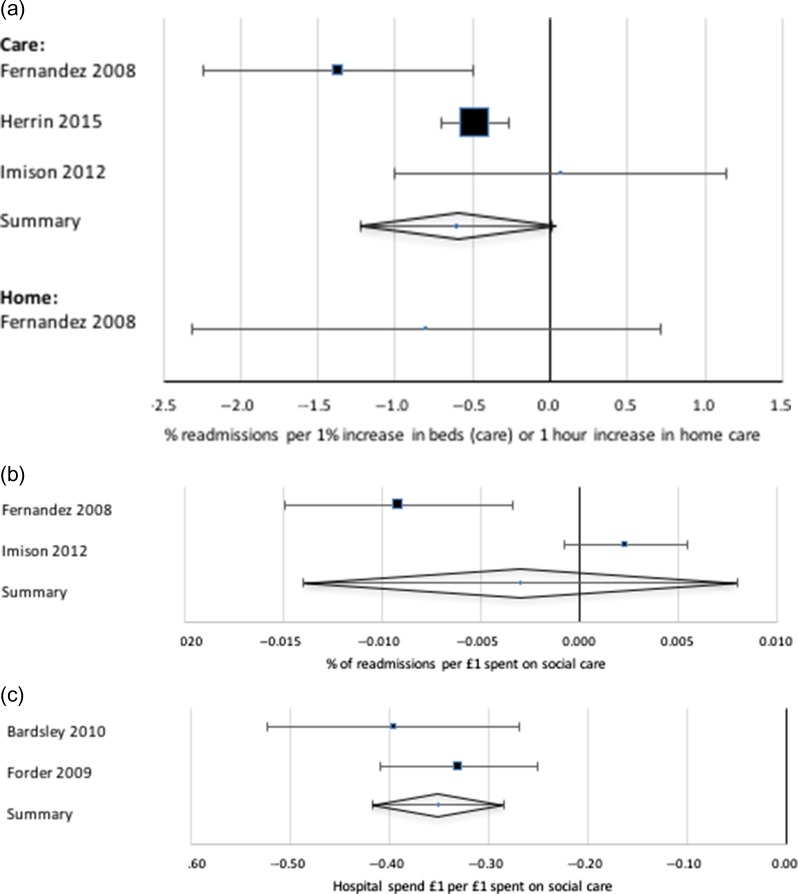

Admissions, readmissions and emergency service use

Emergency admissions and readmissions, emergency department visits and emergency bed use were investigated in a number of studies, though the variables used were less consistent and therefore less suitable for synthesis. Hospital and emergency readmissions were available from three studies. Greater availability of care homes was associated overall with a reduction in rates of emergency readmissions (Figure 3a) [32, 36, 37]. Greater availability of care home beds was also associated with a minor increase in number of emergency department visits in a USA study [39]. The evidence on impact of expenditure on social care on readmissions was inconsistent (Figure 3b): one study with a low quality rating failed to find any clear association, but another good quality study demonstrated a clear effect [32, 36]. In addition, a weak positive relationship between social care expenditure per capita and emergency admissions was described, after adjusting for material disadvantage, in one UK study that could not be combined with others [34]. There was little evidence on the influence of number of hours of homecare on emergency readmissions, though it could be beneficial (Figure 3a) [36].

Figure 3.

Influence of social care and homecare on emergency hospitalisations and costs. (a) Impact of availability of emergency readmissions. (b) Impact of expenditure on emergency readmissions. (c) Impact of social care expenditure on hospital care expenditure.

Healthcare expenditure

Two UK studies looked at the relationship between expenditure on social care and expenditure on healthcare (Figure 3c), both found that for every £1 spent on care homes, there was an estimated reduction in hospital spend [35, 41].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review to synthesise evidence on how the availability and supply of social care influences HCU by older adults. We found that higher expenditure on social care and greater availability of care home beds are associated with fewer readmissions, delayed discharges, and reduced length of stay and expenditure on secondary healthcare services. These findings have important and timely implications for health systems and the care offered to older adults. The evidence underlines the role of access to social care as a mechanism for mediating the use of secondary health services, suggesting that allocating resources to social care may help contain health sector demand, and consequently, rising health sector costs. These are important messages for policy-makers, especially in the UK where access to social care is currently compounded by a shrinking care home market and increasing financial constraints [9, 24], whilst demand continues to rise from an ageing population. In light of recent evidence linking reduced social care expenditure with increased mortality [20], these findings lend further support to the importance of increasing resources for social care.

Our findings also support two contemporary arguments about the consequences of poor access to social care. First, limited availability of care homes with and without nursing may result in delayed hospital discharges. The UK National Audit Office estimates that 2.7 million hospital bed days between 2014 and 2015 were occupied by older adults unable to be discharged due to the poor availability of care home placements or homecare packages, with a cost to the NHS of £820,000,000 [42]. The evidence reviewed here indicates that such poor availability of care homes may indeed culminate in the use of hospital care as a replacement, reflecting Forder’s argument that the two act as substitutes [35]. Such avoidable use of hospital beds may have consequences for the quality of life of older adults, who are otherwise well enough to be cared for in alternative, supported settings. A second argument has been made that poor access to social care to support activities of daily living may result in deteriorating health and thereby increase the need for secondary care [43].

Both of the arguments above are based on the premise that availability and supply of care are closely associated with use of care services. It is also important to acknowledge that there are many potential influences on uptake of social care, including affordability and the presence of family carers. In a recent study, people with the lowest incomes experienced the biggest gap between need for, and receipt of social care [11]. Even when care services are used, service quality may moderate the influence on healthcare utilisation [26, 44].

This review offers a novel and timely contribution to current understanding of how access to social care influences healthcare utilisation. Data were carefully extracted and re-analysed to allow for pooling and the weight of evidence was considered in the conclusions, per standard review procedures. A number of measures and outcome variables were employed by the included studies. This heterogeneity meant that we were unable to produce a pooled estimate of effects, but it is noteworthy that the direction of evidence is consistent across these different metrics and even across different studies from different countries. All included studies were of cross-sectional design, and liable to the usual limitations of observational data. A small number of studies received poor quality ratings because they failed to account for potential bias. Three of these studies were re-analysed, but potential bias due to confounding remains and these studies should be treated with caution [32, 33, 41]. Our review provides no information on the relationship between integrated health and social care services and healthcare utilisation, as studies were excluded if the social care component could not be isolated for analysis. This approach allowed us to produce a focussed review and a clear message, but means that we may have underestimated the influence of social care on healthcare utilisation. It is also important to note that home-based social care was assessed in a minority of included studies.

In summary, this review highlighted three important gaps in the evidence about social care availability and supply. First, outcomes reflected secondary, rather than primary, healthcare use. Older adults comprise a significant proportion of general practice caseloads [45], and primary care is a gateway to the detection of unmet social care needs. Understanding the impact of social care availability on primary care is, therefore, an important consideration and should be addressed in future research. Second, with few studies examining population sub-groups, there was no strong evidence to indicate whose use of healthcare would be most affected by variations in social care availability and supply. The role of material disadvantage requires particular scrutiny. Finally, the paucity of evidence on home-based care is a critical omission, as domiciliary care is key in supporting older adults’ independence in the community.

It is clear from this review that social care has the potential to reduce demand on secondary health services by older adults. At a time of financial stringencies, this is an important message for policy-makers and funders across the world.

Key points.

The influence of social care on healthcare utilisation is a growing policy concern.

No evidence reviews exist to clarify this relationship in relation to older adults.

Adequate supply of social care has the potential to reduce demand on health services.

Evidence about primary care outcomes is lacking.

Evidence about home-based social care is limited.

Supplementary Material

Conflict of interest

GS received a doctoral stipend for the submitted work.

Funding

This review was carried out as part of a PhD studentship funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health.

References

- 1. The King’s Fund A new settlement for health and social care. Final Report. Commission on the Future of Health and Social Care in England. The King’s Fund, 2014.

- 2. Mortimer J, Green M Briefing: The Health and Care of Older People in England 2015: Age UK, 2016.

- 3. The Press Association Leading Medics Heap Pressure On Government To Adequately Fund Social Care. 2016. http://www.careappointments.co.uk/care-news/england/item/40844-leading-medics-heap-pressure-on-government-to-adequately-fund-social-care (accessed 28.11.2016).

- 4. Harper S. Economic and social implications of aging societies. Science 2014; 346: 587–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Comas-Herrera A, Wittenberg R, Costa-Font J et al. Future long-term care expenditure in Germany, Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom. Ageing Soc 2006; 26: 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development Help Wanted? Providing and Paying for Long-Term Care: Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development, 2011.

- 7. Luchinskaya D, Simpson P, Stoye G UK Health and social care spending, 2017.

- 8. Department of Health Care and support statutory guidance: issued under the Care Act 2014: Department of Health, 2014.

- 9. Care Quality Commission The state of health care and adult social care in England 2015/16: Care Quality Commission, 2016.

- 10. Competition and Markets Authority Care homes market study: Competition and Markets Authority, 2017.

- 11. The Health Foundation Health & Social Care Funding Explained. 2017. https://www.health.org.uk/Health-and-social-care-funding-explained (accessed 04.06.2018).

- 12. Helm T. Care for elderly ‘close to collapse’ across UK as council funding runs out. 26 November 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/nov/26/nhs-elderly-care-close-to-collapse (accessed 28.11.2016).

- 13. Fernandez J-L, Forder J. Local variability in long-term care services: local autonomy, exogenous influences and policy spillovers. Health Econ 2015; 24: 146–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fernandez J-L, Snell T, Wistow G Changes in the patterns of social care provision in England: 2005/6 - 2012/13. PSSRU Discussion Paper 2867. Personal Social Services Research Unit: University of Kent, 2013.

- 15. Forder J, Fernandez J-L Geographical differences in the provision of care home services in England. PSSRU Discussion Paper 2824 (revised). Personal Social Services Research Unit: University of Kent, 2012.

- 16. National Audit Office Adult social care in England: an overview. HC 1102 SESSION 2013-14: National Audit Office, 2014.

- 17. Asthana S. Variations in access to social care for vulnerable older people in England: Is there a rural dimension? Commission for Rural Communities2012.

- 18. Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development Public long-term care financing arrangements in OECD countries: OECD, 2011.

- 19. Robertson R, Gregory S, Jabbal J The social care and health systems of nine countries. Commission on the future of health and social care in England.: The King’s Fund, 2014.

- 20. Watkins J, Wulaningsih W, Da Zhou C et al. Effects of health and social care spending constraints on mortality in England: a time trend analysis. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e017722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tennstedt SL, Crawford SL, McKinlay JB. Is family care on the decline? A longitudinal investigation of the substitution of formal long-term care services for informal care. Milbank Q 1993; 71: 601–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pickard L. A growing care gap? The supply of unpaid care for older people by their adult children in England to 2032. Ageing Soc 2013; 35: 96–123. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Local Government Association LGA responds to Institute for Fiscal Studies research on social care spending. 5 April 2017. http://www.local.gov.uk/about/news/lga-responds-institute-fiscal-studies-research-social-care-spending (accessed 19.04.17).

- 24. Local Government Association Adult Social Care Funding: 2016 State of the Nation Report. 2016. http://www.local.gov.uk/documents/10180/7632544/1+24+ASCF+state+of+the+nation+2016_WEB.pdf/e5943f2d-4dbd-41a8-b73e-da0c7209ec12 (accessed 22/03/2017).

- 25. Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development Country Classification July 2016. Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development; 2011.

- 26. Gulliford M, Figueroa-Munoz J, Morgan M et al. What does ‘access to health care’ mean? J Health Serv Res Policy 2002; 7: 186–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016; 5: 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2014. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (accessed 09/01/2017.

- 29. Damiani G. An ecological study on the relationship between supply of beds in long-term care institutions in Italy and potential care needs for the elderly. BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9: 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gaughan J, Gravelle H, Santos R Long term care provision, hospital length of stay and discharge destination for hip fracture and stroke patients: Centre for Health Economics, Department of Economics and Related Studies, University of York, UK, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31. Gaughan J, Gravelle H, Siciliani L Testing the bed-blocking hypothesis: does higher supply of nursing and care homes reduce delayed hospital discharges?: Centre for Health Economics, Department of Economics and Related Studies, University of York, UK, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. Imison C, Poteliakoff E, Thompson J Older people and emergency bed use: exploring variation, 2012.

- 33. Liotta G, Mancinelli S, Scarcella P, Emberti Gialloreti L. Determinants of acute hospital care use by elderly patients in Italy from 1996 to 2006. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012; 54: e364–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reeves D, Baker D. Investigating relationships between health need, primary care and social care using routine statistics. Health Place 2004; 10: 129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Forder J. Long-term care and hospital utilisation by older people: an analysis of substitution rates. Health Econ 2009; 18: 1322–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fernandez J-L, Forder J. Consequences of local variations in social care on the performance of the acute health care sector. Appl Econ 2008; 40: 1503–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Herrin J, St Andre J, Kenward K, Joshi MS, Audet AM, Hines SC. Community factors and hospital readmission rates. Health Serv Res 2015; 50: 20–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holmås TH, Islam MK, Kjerstad E. Interdependency between social care and hospital care: the case of hospital length of stay. Eur J Public Health 2013; 23: 927–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hunold KM, Richmond NL, Waller AE, Cutchin MP, Voss PR, Platts-Mills TF. Primary care availability and emergency department use by older adults: a population-based analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62: 1699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gaughan J, Gravelle H, Siciliani L. Testing the bed-blocking hypothesis: does nursing and care home supply reduce delayed hospital discharges? Health Econ 2015; 24: 32–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bardsley M, Georghiou T, Dixon J Social care and hospital use at the end of life. London: The Nuffield Trust, 2010.

- 42. National Audit Office Discharging older patients from hospital. HC 18 SESSION 2016-17: National Audit Office, 2016.

- 43. Ismail S, Thorlby R, Holder H Focus On: Social care for older people. London: The Health Foundation, Nuffield Trust, 2014.

- 44. Gulliford MC, Figueroa-Munoz J, Morgan M. Meaning of ‘access’ in healthcare In: Gulliford MC, Morgan M, eds. Acces to Health Care. London: Routledge, 2003, p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baird B, Charles A, Honeyman M, Maguire D, Das P Understanding pressures in general practice. The King’s Fund, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.