The ratio of light-driven O2 consumption to gross photosynthetic O2 evolution decreased significantly with increasing CO2, which is probably due to a reduced cost of operating the carbon-concentrating mechanism.

Keywords: Carbon fixation, CO2, cyanobacteria, gross photosynthesis, net photosynthesis, ocean acidification, Trichodesmium

Abstract

As atmospheric CO2 concentrations increase, so too does the dissolved CO2 and HCO3– concentrations in the world’s oceans. There are still many uncertainties regarding the biological response of key groups of organisms to these changing conditions, which is crucial for predicting future species distributions, primary productivity rates, and biogeochemical cycling. In this study, we established the relationship between gross photosynthetic O2 evolution and light-dependent O2 consumption in Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 acclimated to three targeted pCO2 concentrations (180 µmol mol–1=low-CO2, 380 µmol mol–1=mid-CO2, and 720 µmol mol–1=high-CO2). We found that biomass- (carbon) specific, light-saturated maximum net O2 evolution rates (PnC,max) and acclimated growth rates increased from low- to mid-CO2, but did not differ significantly between mid- and high-CO2. Dark respiration rates were five times higher than required to maintain cellular metabolism, suggesting that respiration provides a substantial proportion of the ATP and reductant for N2 fixation. Oxygen uptake increased linearly with gross O2 evolution across light intensities ranging from darkness to 1100 µmol photons m–2 s–1. The slope of this relationship decreased with increasing CO2, which we attribute to the increased energetic cost of operating the carbon-concentrating mechanism at lower CO2 concentrations. Our results indicate that net photosynthesis and growth of T. erythraeum IMS101 would have been severely CO2 limited at the last glacial maximum, but that the direct effect of future increases of CO2 may only cause marginal increases in growth.

Introduction

The ocean is one of the largest readily exchangeable reservoirs of inorganic carbon on Earth and is a major sink for anthropogenic CO2 emissions (Sabine et al., 2004). The ocean’s capacity to sequester atmospheric CO2 is strongly mediated by biological processes (Raven and Falkowski, 1999), where organic matter production and export drive CO2 sequestration. This is important as future emission scenarios predict that atmospheric CO2 will increase from present concentrations (~400 µmol mol–1) to 750 µmol mol–1 or 1000 µmol mol–1 by the end of this century (Raven et al., 2005). This will lead to an increase in the total dissolved inorganic carbon (TIC) in the surface ocean, reducing the pH from an average value of ~8.2 (pre-industrial) to ~7.9 (estimated for 2100) (Zeebe et al., 1999; Zeebe and Wolf-Gladrow, 2001). Ocean acidification therefore favours an increase in seawater CO2 and HCO3– concentration and a decrease in pH and CO32–.

There are still many uncertainties regarding the biological response of key groups of organisms to these changing conditions, which is crucial for predicting future species distributions, primary productivity rates, and biogeochemical cycling. One group of great importance are diazotrophic cyanobacteria (photosynthetic dinitrogen fixers), as they contribute significantly to overall marine primary productivity by providing new nitrogen to many oligotrophic areas of the oceans. The filamentous cyanobacteria Trichodesmium are a colony-forming species that forms extensive surface blooms in the tropical and subtropical oceans (Carpenter and Capone, 1992; Capone et al., 1997; Campbell et al., 2005). Trichodesmium plays a significant role in the N cycle of the oligotrophic oceans; fixing nitrogen in an area corresponding to half of the Earth’s surface (Davis and McGillicuddy, 2006) and representing up to 50% of new production in some oligotrophic tropical and subtropical oceans (Capone, 2005). The annual marine N2 fixation is currently estimated at between 100 Tg and 200 Tg N per year (Gruber and Sarmiento, 1997; Karl et al., 2002), of which Trichodesmium spp. contribute between 80 Tg and 110 Tg of fixed N2 to open ocean ecosystems (Capone et al., 1997).

Cyanobacteria have performed oxygenic photosynthesis for ~2.7 billion years (Buick, 2008). During that time, CO2 concentrations have declined and O2 concentrations increased, thus exerting an evolutionary pressure to form a mechanism to reduce the impact of photorespiration on photosynthetic CO2 fixation. Despite cyanobacterial Rubisco having a relatively low affinity for CO2, cyanobacteria achieve high photosynthetic rates by virtue of an intracellular carbon-concentrating mechanism (CCM), which thereby reduces the diversion of energy into oxygenation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP), the first step in photorespiration (Schwarz et al., 1995; Kaplan and Reinhold, 1999). In addition, the CCM can aid in the dissipation of excess light energy as well as maintaining an optimal intracellular pH (Badger et al., 1994; Kaplan and Reinhold, 1999).

Cyanobacteria have a unique ability to perform both photosynthesis and respiration simultaneously in the same cellular compartment (Nagarajan and Pakrasi, 2001). The thylakoid membranes of cyanobacteria contain both respiratory and photosynthetic electron transport chains, sharing the plastoquinone and plastocyanin pools and the Cyt b6f complex. In contrast, the cytoplasmic membrane is only capable of performing respiratory electron transport (Nagarajan and Pakrasi, 2001). Thus, it is common in cyanobacteria for respiratory electron transport to be inhibited at low light intensities as photosynthesis increases in the thylakoid membranes (Kana, 1992). However, in Trichodesmium there remains the possibility that photosynthetic and respiratory metabolism differs between diazocytes (where N2 fixation occurs) and other cells within a trichome.

Previous studies report an increase in growth and productivity (CO2 and N2 fixation) of T. erythraeum IMS101 as well as changing elemental composition in response to future CO2 concentrations (~750–1000 µmol mol–1) (Barcelos e Ramos et al., 2007; Levitan et al., 2007, 2010a; Kranz et al., 2010; Spungin et al., 2014; Hutchins et al., 2015; Boatman et al., 2017, 2018a, b), although, as discussed in Boatman et al. (2018a), the magnitude of the responses often differs between studies. Due to the significant contribution that Trichodesmium makes to biogeochemical cycles and the predicted change in inorganic carbon (Ci) speciation over the coming decades, we performed a systematic experiment to assess how the photosynthetic physiology of T. erythraeum IMS101 was affected by acclimation to varying CO2. We ensured that the Ci chemistry and all other growth conditions were well defined, with cultures fully acclimated over long time periods (~5 months) to achieve balanced growth. We assessed the dark respiration, light absorption, and the light dependencies of gross O2 evolution and O2 consumption across different CO2 conditions. We discuss how the responses that we observed may be related to N2 fixation and changes in the cost of operating the CCM.

Materials and methods

Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 was semi-continuously cultured to achieve fully acclimated balanced growth at three target pCO2 concentrations (180, 380, and 720 µmol mol–1), under saturating light intensity (400 µmol photons m–2 s–1), a 12/12 h light/dark (L/D) cycle, and an optimum growth temperature (26 ± 0.7 °C) for ~5 months (~40, 70, and 80 generations at low-, mid-, and high-CO2, respectively).

Experimental set-up

Cultures of T. erythraeum IMS101 were grown in standard YBCII medium (Chen et al., 1996) under diazotrophic conditions (N2 only) in 1.5 litre volumes in 2 litre Pyrex bottles that had been acid-washed and autoclaved prior to culturing. Illumination was provided side-on by fluorescent tubes (Sylvania Luxline Plus FHQ49/T5/840). Cultures were constantly mixed using magnetic PTFE stirrer bars and aerated with a filtered (0.2 µm pore) air mixture at a rate of ~200 ml s–1. The CO2 concentration was regulated (±2 µmol mol–1) by mass-flow controllers (Bronkhorst, Newmarket, UK) and CO2-free air was supplied by an oil-free compressor (Bambi Air, UK) via a soda-lime gas-tight column that was mixed with a 10% CO2-in-air mixture from a gas cylinder (BOC Industrial Gases, UK). The CO2 concentration in the gas phase was continuously monitored by an infra-red gas analyser (Li-Cor Li-820, Lincoln, NE, USA), calibrated weekly against a standard gas (BOC Industrial Gases).

Cultures were kept at the upper section of the exponential growth phase through periodic dilution with new growth media at 3–5 d intervals. Daily growth rates were quantified from changes in baseline fluorescence (Fo) measured between 09.00 h and 10.30 h on dark-adapted cultures (20 min) using a FRRfII FastAct Fluorometer System (Chelsea Technologies Group Ltd, UK). As detailed in Boatman et al. (2018a), cultures were deemed fully acclimated and in balanced growth when both the slope of the linear regression of ln(Fo) and the ratio of live-cell to acetone-extracted Fo were constant following every dilution with fresh YBCII medium.

The Ci chemistry was measured prior to the dilution of each culture with fresh media, where exactly 20 ml of culture from each treatment was filtered through a swinnex filter (25 mm, 0.45 µm pore, glass fibre filter): 15 ml into a plastic centrifuge tube (no headspace) for TIC analysis (Shimadzu TOC-V Analyser & ASI-V Autosampler), and 5 ml into a plastic cryogenic vial (Sigma-Aldrich V5257-250EA; no headspace) for pH analysis.The bicarbonate (HCO3–), carbonate (CO32–), and CO2 concentrations were calculated via CO2SYS as described in Boatman et al. (2017). Overall, the CO2 drawdown in the cultures ranged between 49 µmol mol–1 and 90 µmol mol–1 for all CO2 treatments (Table 1) and exhibited a negligible CO2 drift over a diurnal cycle (see Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online).

Table 1.

The growth conditions (±SE) achieved for T. erythraeum IMS101 when cultured at three target gas phase ChlCO2 concentrations (low=180 µmol mol–1, mid=380 µmol mol–1, and high=720 µmol mol–1), saturating light intensity (400 µmol photons m–2 s–1), and optimal temperature (26 °C)

| Variables | Units | Low-CO2 | Mid-CO2 | High-CO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | – | 8.461 | 8.175 | 7.905 |

| H+ | nM | 3.5 (0.1) | 6.7 (0.1) | 12.5 (0.2) |

| AT | µM | 2427 (32) | 2490 (51) | 2444 (42) |

| TCO2 | µM | 1797 (30) | 2076 (44) | 2204 (37) |

| HCO3– | µM | 1356 (30) | 1773 (37) | 2008 (32) |

| CO32– | µM | 436 (9) | 295 (8) | 179 (5) |

| CO2 | µM | 3.3 (0.2) | 8.2 (0.2) | 17.4 (0.3) |

| NH4+ | mM | 1.00 (0.12) | 1.06 (0.08) | 1.02 (0.06) |

| NO3– | mM | 0.33 (0.05) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.02) |

| n | 76 | 32 | 28 |

Individual pH values were converted to a H+ concentration, allowing a mean pH value to be calculated. Dissolved inorganic NH4+ was determined using the phenol-hypochlorite method as described by Solorzano (1969), while dissolved inorganic NO3– was determined using the spectrophotometric method as described by Collos et al. (1999).

Gross and net O2 exchange

Light-dependent rates of O2 production and consumption were measured on four biological replicates per CO2 treatment, using a membrane inlet mass spectrometer (MIMS) and an 18O2 technique modified from McKew et al. (2013).

MIMS samples were prepared by placing 300 ml of culture in a large gas-tight syringe, and gently bubbled with N2 gas for ~20 min to reduce the 16O2 concentration. The headspace was removed, and 2 ml of 18O2 gas (CK Gas Products, UK; 99% purity) was added and mixed by continuously inverting the syringe for 20 min. During this process, the culture was maintained at a low light intensity (<10 µmol photons m–2 s–1) and at growth temperature (26 °C). Samples were incubated using a series of 6 ml glass stopper, gas-tight test tubes, which were cleaned with detergent, acid-washed (10% HCl for 1 d), and rinsed with deionized water (Millipore Milli-Q Biocel, ZMQS60FOI) prior to use. Glass beads were placed inside each test tube, allowing the sample to be mixed throughout the incubation. The 18O2-enriched culture was quickly dispensed into the gas-tight glass test tubes, sealed using ground glass stoppers (no headspace), and immediately placed into a temperature-controlled (26 °C) incubator. A white light-emitting diode (LED) block (Iso Light 400, Technologica, Essex, UK) was positioned at one end of the incubator, generating light intensities ranging from 10 µmol photons m–2 s–1 to 1100 µmol photons m–2 s–1.

For each replicate, 24 test tubes were incubated across the light gradient, a minimum of 10 test tubes were used to determine the initial concentration of O2 isotopes, and an additional four test tubes were incubated in the dark (26 °C) to determine dark respiration rates. All photosynthesis–light (P–E) response curves were measured at the same time of day between 4 h and 6 h into the photo-phase of the L/D cycle and were incubated for between 60 min and 120 min. Culture densities for these experiments ranged from 80 µg Chl a l–1 to 240 µg Chl a l–1.

Changes in 16O2 and 18O2 and thus O2 consumption (U0) and O2 evolution (E0) were calculated using the following equations (Radmer and Kok, 1976);

| (1) |

| (2) |

where U0 is the rate of O2 consumption and E0 is the rate of gross O2 evolution. C-specific rates were obtained by dividing U0 and E0 by the concentration of particulate organic carbon (POC). Rates were also normalized to Chl a and particulate organic nitrogen (PON), and are presented in Supplementary Figs S2 and S3.

The P–E curves for gross (E0C) and net O2 exchange (PnC=E0C–U0C) were fitted to the following equations from Platt and Jassby (1976);

| (3) |

| (4) |

where E0C,max and PnC,max are the carbon-specific maximum gross and net O2 evolution rates; αgC and αnC are the carbon-specific initial light-limited slopes for gross and net photosynthesis; RdC is the dark respiration rate; and E is the light intensity (µmol photons m–2 s–1). Curve fitting was performed on each biological replicate separately to calculate mean (±SE) curve fit parameterizations (Sigmaplot 11.0).

The maximum quantum efficiencies of gross (ϕm,g) and net (ϕm,n) O2 evolution were calculated as follows;

| (5) |

| (6) |

where the C-specific initial slope for gross (αgC) or net (αnC) O2 evolution, spectrally corrected to the culturing LEDs (Supplementary Fig. S6), was divided by the C-specific, spectrally corrected effective light absorption coefficient (aC,eff).

Spectrophotometric Chl a and POC analysis

Samples for the determination of Chl a and POC were collected with each light–response curve, while PON was calculated from the measured POC using the CO2-specific C:N ratio reported in Boatman et al. (2018a). For measurements of Chl a and POC, two 100 ml samples from each culture were vacuum-filtered onto pre-combusted 25 mm glass fibre filters (0.45 µm pore; Fisherbrand FB59451, UK). The first filter was dried at 60 °C and the POC quantified using a TC analyser (Shimadzu TOC-V Analyser & SSM-5000A Solid Sample Combustion Unit). The second filter was placed in 5 ml of 100% methanol, homogenized, and extracted overnight at –20 °C, before being centrifuged at 12 000 g for 10 min, and a 3 ml aliquot of the supernatant added to a quartz cuvette. The absorption spectrum (400–800 nm) was measured using a (Hitachi U-3000, Japan) spectrophotometer and the Chl a concentration (µg l–1) was calculated using the following equation (Ritchie, 2008);

| (7) |

where Abs665 and Abs750 are the baseline-corrected optical densities of the methanol-extracted sample at 665 nm and 750 nm; VolE is the volume of the solvent used for extraction (i.e. 5 ml); VolF is the volume of culture filtered (i.e. 100 ml), and 12.9447 is a cyanobacteria-specific Chl a coefficient for 100% methanol extraction.

Supporting spectrophotometric measurements were made on live cells using an integrating sphere to determine the in vivo light absorption (Supplementary File SI). From this we determined biomass-specific (Chl a, C, and N) light absorption coefficients under the varying CO2 treatments (Supplementary Fig. S4), reconstructed the light absorption spectra from photosynthetic pigment spectra (Supplementary File SII; Supplementary Table S1), and calculated maximum quantum efficiencies of gross and net O2 evolution (Table 3).

Table 3.

The physiological parameters (±SE) of the C-specific light–response curves for the gross and net photosynthetic O2 evolution of T. erythraeum IMS101 (n=4) measured using the MIMS light source

| Parameters | Units | Low-CO2 | Mid-CO2 | High-CO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross O2 evolution | ||||

| E0C,max | mmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1 | 1.875 (0.118) A | 3.795 (0.175) C | 2.973 (0.158) B |

| Ek | µmol photons m-2 s–1 | 277 (15) | 250 (20) | 281 (15) |

| αgC | µmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1 (µmol photons m-2 s-1)–1 | 6.78 (0.33) A | 15.35 (0.82) C | 10.58 (0.18) B |

| ϕm,g | mol O2 (mol photons)–1 | 0.037 (0.004) | 0.042 (0.004) | 0.045 (0.003) |

| Net photosynthesis | ||||

| PnC,max | mmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1 | 1.131 (0.061) A | 2.534 (0.287) B | 2.312 (0.140) B |

| Ek | µmol photons m–2 s–1 | 300 (41) | 270 (24) | 270 (10) |

| αnC | µmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1 (µmol photons m–2 s–1)–1 | 3.94 (0.46) A | 9.48 (1.02) B | 8.57 (0.35) B |

| RdC | mmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1 | –0.600 (0.078) | –0.644 (0.132) | –0.659 (0.013) |

| ϕm,n | mol O2 (mol photons)–1 | 0.020 (0.002) A | 0.026 (0.003) A | 0.037 (0.002) B |

| Slopes | ||||

| PnC versus E0C | Dimensionless | 0.571 (0.028) A | 0.646 (0.046) A | 0.791 (0.017) B |

| U0C versus E0C | Dimensionless | 0.429 (0.028) B | 0.354 (0.046) A | 0.209 (0.017) A |

| U0C versus PnC | Dimensionless | 0.701 (0.073) B | 0.553 (0.111) B | 0.254 (0.024) A |

Abbreviations: E0C,max, the C-specific maximum gross O2 evolution rate; PnC,max, the C-specific maximum net O2 evolution rate; Ek, the light saturation parameter; αgC and αnC are the C-specific initial slopes of the light–response curve for net and gross photosynthesis; ϕm,g and ϕm,n are the maximum quantum efficiencies of gross and net O2 evolution calculated using the absorption coefficients reported in Supplementary Table S1; RdC, the C-specific dark respiration rate; Slope=the slope of the regression of E0C against PnC, E0C against O2 uptake (U0C), and U0C against PnC. Letters indicate significant differences between CO2 treatments (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post-hoc test; P<0.05); where B is significantly greater than[A, and C is significantly greater than B and A.

Results

Growth rate, cell composition, and light absorption

Balanced growth rates increased from 0.2 d–1 at low-CO2 to 0.34 d–1 at mid-CO2 and 0.36 d–1 at high-CO2 (Table 2). Chl a:C ratios were lowest under low-CO2 conditions and were significantly higher in the mid-CO2 treatment relative to the low- and high-CO2 treatments (Table 2).

Table 2.

The mean (±SE) balanced growth rate and Chl a:C ratio for T. erythraeum IMS101 when acclimated to three target CO2 concentrations (low=180 µmol mol–1, mid=380 µmol mol–1, and high=720 µmol mol–1), saturating light intensity (400 µmol photons m–2 s–1), and optimal temperature (26 °C)

| Variables | Units | Low-CO2 | Mid-CO2 | High-CO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth rate | d–1 | 0.198 (0.027) A | 0.336 (0.026) B | 0.361 (0.020) B |

| Chl a:C | g:mol | 0.052 (0.003) A | 0.089 (0.003) C | 0.066 (0.003) B |

Abbreviations: Chl a:C ratios are g:mol (n=9 at low-CO2, n=6 at mid- and high-CO2). Letters indicate significant differences between CO2 treatments (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post-hoc test; P<0.05); where B is significantly greater than A, and C is significantly greater than B and A.

Light dependence of O2 exchange

The C-specific maximum rate (E0C,max) and initial slope (αgC) of light-dependent gross photosynthesis were significantly higher in the mid-CO2 treatment relative to the low- and high-CO2 treatments (Table 3). Conversely, the light saturation parameter (Ek=E0C,max/αgC) for gross O2 evolution (Table 3) and the maximum quantum efficiency of gross O2 evolution (ϕm,g=αgC/aC,eff) (Table 3) did not vary significantly amongst the CO2 treatments due to co-variation of αgC and E0C,max.

The C:N ratios reported by Boatman et al. (2018a) for the low-, mid-, and high-CO2 treatments (7.9, 7.8, and 7.3 mol:mol, respectively) were not significantly different. As such, the CO2 response of N-specific maximum rates and light-limited initial slopes of gross O2 evolution were comparable with C-specific rates (Supplementary Fig. S2; Supplementary Table S2). The ~2-fold variability of E0C,max and αgC was largely due to differences in the Chl a:C ratio, with the Chl a-specific light absorption varying by only 1% across CO2 treatments (Supplementary Table S1).

The C-specific dark respiration rates (RdC) varied by ~10% amongst CO2 treatments (Table 3). The maximum net O2 evolution rate (PnC,max) approximately doubled from the low-CO2 to the mid- and high-CO2 treatments, but did not differ between mid- and high-CO2, with the initial slope (αnC) showing a similar pattern to PnC,max (Table 3). Similar responses were observed for the maximum rate (VC,max) and initial slope (Affinity) of the CO2 dependency of C fixation as reported in Boatman et al. (2018a).

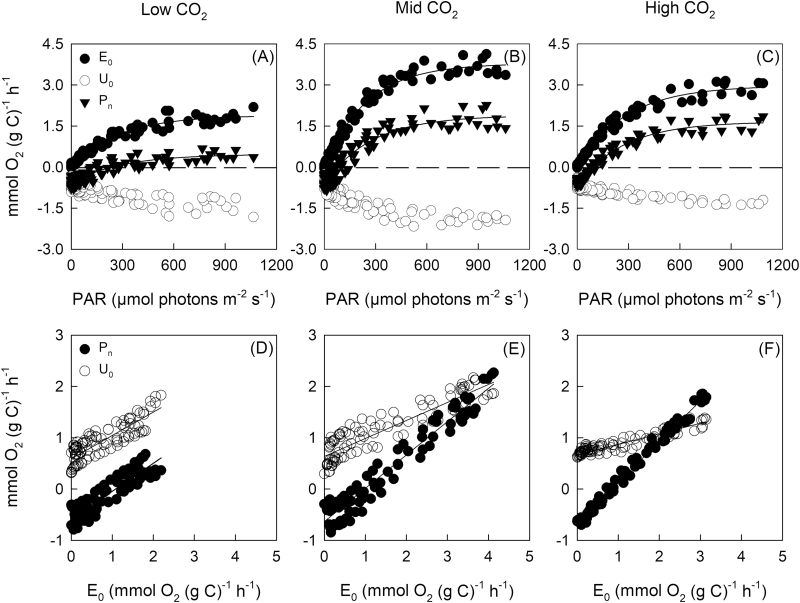

The relationship between Pn and E0 was linear (Fig. 1), with the slope increasing by ~13% from low- to mid-CO2 and by 22% from mid- to high-CO2 (Table 4). This linear relationship indicates that light-dependent O2 consumption (U0C) was a constant proportion of gross O2 evolution (E0C), independent of light intensity under each of the CO2 treatments. Subtracting the slope from unity gives the ratio of light-dependent O2 consumption to gross O2 evolution, which declined significantly from 0.79 at high-CO2 to 0.65 at mid-CO2 and 0.57 at low-CO2.

Fig. 1.

The C-specific light–response curves for gross O2 evolution, O2 consumption, and net photosynthesis (n=4) (A–C) and the relationship between gross net O2 evolution and net O2 evolution or O2 consumption (D–F) for T. erythraeum IMS101. Oxygen evolution rates are normalized to a carbon basis [mmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1]. The dashed line represents where gross O2 evolution equals O2 consumption (i.e. net photosynthesis=0). Note, Chl a- and N-specific light–response curves are reported in Supplementary Figs S2 and S3.

Table 4.

The photosynthetic quotients (±SE) for T. erythraeum IMS101, calculated from the light-saturated, maximal rates of carbon-specific O2 evolution, and the C fixation rates

| Parameters | Units | Low-CO2 | Mid-CO2 | High-CO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photosynthetic quotient | ||||

| E0C/VC | mol O2 (mol C)–1 | 1.98 (0.10) | 1.99 (0.04) | 1.28 (0.04) |

| PnC/VC | mol O2 (mol C)–1 | 1.14 (0.07) | 1.29 (0.11) | 1.01 (0.05) |

VC was calculated as VC=(VC,max×[CO2])/(Km+[CO2]) using the value of Km from Boatman et al. (2018a) and [CO2] from Table 1. E0C was calculated as E0C=E0C,max×[1–e(–α×E/E0C,max)] and PnC was calculated as PnC=PnC,max×[1–e(–α×E/PnC,max)] using E=400 µmol photons m–2 s–1 and values of Ek from Table 3.

Photosynthetic quotient

We calculated the photosynthetic quotient (PQ) as:

| (8) |

where PnC is the C-specific net O2 evolution rate (E0–U0) and VC is the C-specific C-fixation rate reported by Boatman et al. (2018a), with both PnC and VC calculated at the growth light intensity (400 mmol photon m–2 s–1) and growth CO2 concentration (Table 1). The PQ calculated in this way (Table 4) did not vary systematically amongst the CO2 treatments, averaging about 1.15 mol O2 mol CO2–1.

A second value of PQ was calculated by dividing E0C by VC for C fixation under the corresponding conditions, which increased from 1.3 mol O2 mol CO2–1 in the high-CO2 treatment to ~2.0 mol O2 mol CO2–1 for the low- and mid-CO21 treatments (Table 4), reflecting the increase in light-dependent O2 consumption with decreasing CO2.

Discussion

Effect of acclimation to variation of inorganic chemistry on growth rates and the Chl a:carbon ratio

The increased growth rate from low- (180 µmol mol–1) to mid- (380 µmol mol–1) and high-CO2 (720 µmol mol–1) was similar to previous findings (Barcelos e Ramos et al., 2007; Boatman et al., 2017, 2018b). Whilst not statistically significant, balanced growth rates were ~10% greater at high-CO2 than at mid-CO2. The magnitude of this increase is comparable with several recent studies, which show rates increasing by 7–26% at similar CO2 concentrations (Barcelos e Ramos et al., 2007; Hutchins et al., 2007; Levitan et al., 2007; Kranz et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2011; Boatman et al., 2017).

We observed that the Chl a:C ratio varied 1.7-fold, peaking in the mid-CO2 treatment (Table 2). This is in contrast to previous research which showed that both Chl a:C and growth rate were largely independent of CO2 in Trichodesmium (Kranz et al., 2009, 2010). One possible explanation for the difference between our study and previous research is that we grew Trichodesmium at a higher light intensity (400 µmol photons m–2 s–1 in our experiments; 200 µmol photons m–2 s–1 used by Kranz et al.), and that pigment synthesis was down-regulated in our low-CO2 treatment where CO2 limited growth rate. Down-regulation of pigment synthesis by CO2 limitation on growth was also observed previously for Synechococcus by Fu et al. (2007). In contrast, we hypothesize that the reduction in Chl a:C that we observed from mid-CO2 to high-CO2 may be due to the reduced cost of operating a CCM at high-CO2.

Dark respiration and maintenance metabolic rate

Maintenance metabolism is a collection of key functions necessary to preserve cell viability that are commonly assumed to be independent of growth rate and as such can be estimated by extrapolating the relationship between light-limited growth rate and light intensity (E) to E=0 (Geider and Osborne, 1989). We estimated a maintenance metabolic rate [0.034 d–1 ~0.12 mmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1] from previous observations of the light dependence of Trichodesmium growth (Boatman et al., 2017; Supplementary Fig. S5). In the dark, Trichodesmium has a respiration rate [Rd=0.60–0.66 mmol O2 (g cellular C)–1 h–1] (Table 3) that is about five times higher than what is needed to maintain cellular metabolism. In most cyanobacteria, dark respiration rates (Rd) are a small proportion of light-saturated net O2 production rates (Pn,max) (Matthijs and Lubberding, 1988; Geider and Osborne, 1989). In contrast, we observed Rd rates that were a high proportion of light-saturated photosynthesis, consistent with other reports of high ratios of Rd to net photosynthesis in natural (Kana, 1993) and cultured Trichodesmium (Berman-Frank et al., 2001; Kranz et al., 2010; Eichner et al., 2017). For Trichodesmium spp., a high Rd is required to support the rates of N2 fixation measured in darkness. N2 fixation is energetically expensive, requiring a minimum consumption of 13 ATP and 6 reducing equivalents per N2 fixed, assuming complete recycling of H2 produced by nitrogenase to recover ATP.

From our observed growth rates and the C:N ratio reported by Boatman et al. (2018a), we calculate that the O2 consumption rate required to support the level of N2 fixation needed for growth is ~0.5 mmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1 in cells grown under low-CO2, increasing to ~1 mmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1 in cells grown under high-CO2 (Supplementary File SIII). These rates are of the same order as Rd [0.60–0.66 mmol O2 (g C)–1 h–1] (Table 3), indicating that Rd may provide a substantial proportion of the ATP and reductant required for N2 fixation in the light. Significantly, Kana (1993) found that the addition of DCMU to illuminated cells caused the rate of oxygen uptake (U0) to decline to the rate observed in darkness, opening up the possibility that continuation of the ‘dark’ respiration rate in the light provides at least some of the energy required for N2 fixation.

Effect of acclimation to pCO2 on gross photosynthesis and photosynthetic quotients

Carbon-specific rates are directly related to changes in the specific growth rate, as both rates can be expressed in equivalent units of inverse time (e.g. h–1 or d–1). However, due to differences in the Chl a:C ratio (Table 2), Chl a-specific maximum rates (E0Chl,max) and initial slopes (αgChl) of light-dependent gross photosynthesis did not differ significantly between CO2 treatments (Supplementary Fig. S3; Supplementary Table S3), an observation that is consistent with the findings reported by Levitan et al. (2007) and Eichner et al. (2014). We suggest that the reduced Chl a:C ratio at low-CO2 relative to mid-CO2 is probably due to the cost of up-regulating the CCM, whereas the reduced Chl a:C ratio at high-CO2 relative to mid-CO2 may be due to an increase in carbohydrate storage granules.

In contrast to E0C,max, which clearly peaked in the mid-CO2 treatment, the maximum net O2 evolution rate (PnC,max) increased from low- to mid-CO2 but was not statistically different between mid- and high-CO2 treatments (Table 3). The 2-fold increase of PnC,max from low- to mid- and high-CO2 is consistent with the effect of CO2 on growth rate.

Dividing the rate of net O2 evolution (PnC) by the rate of C fixation under comparable light and CO2 conditions gave values for the PQ that ranged from 1.0 mol O2 to 1.3 mol O2 evolved per mol CO2 fixed (Table 4). A PQ of 1.0 is expected if carbohydrate is the major product of photosynthesis as PnC measures the light-driven electron transport from PSII to NADPH, which then feeds into CO2 assimilation by the Calvin cycle. A PQ >1.0 is expected if recent photosynthate is used in synthesis of compounds that are more reduced than carbohydrates (e.g. lipid) and/or that photosynthetically generated reductant is used to power N2 fixation and N assimilation into amino acids. Alternatively or in addition, a slightly higher PQ may be required if photosynthetically generated reductant is required for operation of the CCM, or for salvaging CO2 that leaks from carboxysomes by conversion of CO2 to HCO3– by NDH-I4 (Price et al. (2008). This corroborates our findings, where under high-CO2, when the CCM is probably down-regulated, we observed a PQ value close to 1.0. Conversely at low- and mid-CO2, when more energy is required for the CCM, we observed a PQ value >1.0.

Effect of acclimation to pCO2 on light-stimulated O2 consumption and the relationship between net and gross O2 evolution

We found that O2 consumption rates (U0) of Trichodesmium increased markedly with light intensity, with U0 saturating at a similar light intensity to gross O2 evolution (Fig. 1). This suggests that light-driven U0 increased in parallel with gross O2 evolution and that dark respiration continued at similar rates in the light and dark. Previously, Kana (1993) observed a very slight decline in U0 between darkness and low-light intensity in natural Trichodesmium colonies, followed by parallel increases of U0 and O2 evolution (E0) with increasing light. Kana (1993) attributed the light-stimulated component of U0 to the Mehler reaction, as the addition of DCMU to illuminated cells caused U0 to decline to the rate observed in darkness.

The slope of the dependence of U0C on E0C decreased with increasing growth CO2 from 0.43 in cultures grown under low-CO2 to 0.21 in cultures grown under high-CO2 (Table 3). Thus, the light-driven component of U0 decreased from ~43% of E0 in the low-CO2 culture to 21% of E0 in the high-CO2 culture. Pseudocyclic photophosphorylation coupled to the consumption of O2 associated with the Mehler reaction can provide ATP that may be used to support N2 fixation, CO2 fixation, or for operating a CCM (Miller et al., 1988). The linearity between U0 and E0 suggests that light-dependent O2 consumption may be required to balance the ratio of ATP production to NADPH production in the light reactions of photosynthesis. As the photon efficiency of ATP production by pseudocyclic photophosphorylation is the same as that of photophosphorylation driven by linear photosynthetic electron transport (LPET) (Baker et al., 2007), our results suggest that 26% more ATP than can be generated by LPET is required by cells growing under high-CO2, increasing to 55% more ATP in cells growing under mid-CO2 and 75% more ATP in cells growing under low-CO2. Much of the additional ATP that could be generated by pseudocyclic photophosphorylation may be accounted for by the ATP requirements for CO2 fixation by the Calvin cycle (1.5 ATP/e–) and N2 fixation (2.1 ATP/e–) being greater than the ratio of ATP to reducing equivalents generated by LPET (1.25 ATP/e–). At low-CO2, the increase in U0 may also be required to operate a CCM, as observed in the freshwater Synechococcus (Miller et al., 1988).

An estimate of the cost of operating the CCM

Stimulation of growth and productivity of T. erythraeum IMS101 in response to increasing CO2 is commonly attributed to reductions in the amount of energy required for establishing, maintaining, and operating a CCM (Hutchins et al., 2007, 2015; Levitan et al., 2007; Garcia et al., 2011). Two aspects for the cost of operating the CCM in Trichodesmium are those for HCO3– transport into the cell, which must balance CO2 fixation and CO2 leakage, and those for retaining inorganic C within the cell by converting CO2 that diffuses from the carboxysome to HCO3– via the NDH-I4 CO2 uptake/salvage system. The cost of HCO3– transport of ~1 ATP for each C transported into the cell (Raven et al., 2014) could be supplied by either cyclic photosynthetic electron transfer around PSI or pseudocyclic photosynthetic electron transfer linked to the Mehler reaction. As the ratio of CO2 leakage to gross inorganic C uptake has been found to be independent of pCO2 over the range of 150–1000 µmol mol–1 (Kranz et al., 2009, 2010), the ATP required for HCO3– transport will also be independent of pCO2.

Rather than fuelling ATP production by pseudocyclic electron transport, light-dependent O2 consumption may be a consequence of operating the NDH-I4 CO2 uptake/salvage system. For Trichodesmium, the NDH-I4 protein is thought to reduce the efflux of CO2 from the cell, converting it to HCO3– but at a cost of consuming reducing equivalents [NADPH or reduced ferredoxin (Fd)] (Price et al., 2008).

The stoichiometry based on NADPH as the electron donor can be represented as:

| (9) |

If NDH-I4 activity is employed to minimize CO2 effluxes, then the rate of O2 consumption associated with this process would be expected to decrease with increases of extracellular CO2 concentration. As NADPH consumption by this mechanism is closely linked in time and space to NADPH production via LPET, this process would be inhibited by DCMU in a similar manner to the Mehler reaction.

Roles of photosynthetic and respiratory metabolism in N2 fixation

Increased pCO2 will not only stimulate CO2 fixation, but will also stimulate N2 fixation (dependent on carbon skeletons for sequestration of the ammonium produced) and growth in Trichodesmium (Barcelos e Ramos et al., 2007; Hutchins et al., 2007; Levitan et al., 2007, 2010b; Kranz et al., 2009, 2010). This is probably in response to energy relocation from the CCM (Badger et al., 2006; Kranz et al., 2011) toward CO2 and N2 fixation (Levitan et al., 2007; Kranz et al., 2011).

Diazocytes may use the light reactions of photosynthesis to provide some or most of the ATP required to support N2 fixation either through cyclic photophosphorylation associated with electron transfer around PSI or through pseudocyclic photophorylation involing LPET from H2O to O2 involing both PSII and PSI. However, LPET evolves O2, which is known to inactivate nitrogenase. Enhanced rates of the Mehler reaction, unless uncoupled from O2 evolution at PSII, will not affect the O2 balance of diazocytes. However, if respiration provides the ATP for N2 fixation, then sugars and/or organic acids may be produced by photosynthesis in diazocytes prior to the initiation of N2 fixation (temporal separation of CO2 fixation from N2 fixation) or in other cells within the trichome and transported laterally into the diazocytes (spatial separation of CO2 fixation from N2 fixation).

Temporal separation of N2 fixation from photosynthetic O2 evolution may be achieved if glycogen that accumulates in diazocytes prior to the onset of N2 fixation provides the reducing equivalents and ATP to fuel N2 fixation, perhaps supplemented by high rates of cyclic photosynthetic electron transfer around PSI to generate ATP. Temporal separation is consistent with the pattern of CO2 fixation and N2 fixation observed in Trichodesmium where the former peaks earlier in the day than the latter (Berman-Frank et al., 2001). Spatial separation has been observed in heterocystous cyanobacteria where transport of sugars into heterocysts from surrounding cells can be respired to fuel N2 fixation (Wolk, 1968; Böhme, 1998). Although we are not aware of direct evidence for rapid transfer of metabolites amongst cells along a trichome, such a transfer would be consistent with observations of Finzi-Hart et al. (2009), showing that all cells within a Trichodesmium trichome show the same temporal pattern of accumulation and mobilization of cyanophycin granules and the same temporal pattern of labelling with 13CO2 and 15N.

Conclusion

In this study, we accredit the bell-shaped CO2 response of the C-specific maximum gross photosynthesis rates (E0C,max) to the CCM, where the 2-fold increase in E0C,max from low- to mid-CO2 supports the almost 2-fold increase in balanced growth rates and the decrease in E0C,max from mid- to high-CO2 is due to less expenditure on the CCM whilst cells grow at a similar rate.

Our results indicate a significant decrease in the ratio of the rate of light-driven O2 consumption to the rate of gross photosynthetic O2 evolution with increasing CO2, which probably arises from a reduced cost of operating the CCM. In addition, dark respiration appears to be sufficient to provide much of the energy required to support significant rates of N2 fixation, even in the light.

We have not extrapolated our findings to a full day as light–response curves were measured at one time point and Trichodesmium exhibits pronounced diurnal variability in photosynthetsis and N2 fixation (Berman-Frank et al., 2001). In addition, extrapolating to future conditions in the natural environment should consider (i) the impact of adaptation of Trichodesmium to future conditions (Hutchins et al., 2015); (ii) strain and clade variability (Hutchins et al., 2013); and (iii) additional integrated effects of abiotic variables other than CO2 (i.e. light intensity, temperature, and nutrients such as P and Fe) (Walworth et al., 2016).

In the context of open oceans, nutrient-replete Pn and growth rates of T. erythraeum IMS101 would have been severely CO2 limited at the last glacial maximum relative to current conditions. Future increases of CO2 may not significantly increase growth and productivity of Trichodesmium, although increases in key stoichiometric ratios (N:P and C:P) as reported by Boatman et al. (2018a) may affect bacterial and zooplankton metabolism, the pool of bioavailable N, the depth at which sinking organic matter is remineralized, and consequently carbon sequestration via the biological carbon pump (Mulholland et al., 2004; McGillicuddy, 2014). These responses could serve as a negative feedback to climate change by increasing new N and C production, thereby increasing the organic carbon sinking to the deep ocean.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Table S1. The measured and modelled effective light absorption coefficients and relative photosynthetic pigment contribution to the total light absorption.

Table S2. The physiological parameters of the N-specific light–response curves for gross and net photosynthetic O2 evolution of T. erythraeum IMS101.

Table S3. The physiological parameters of the Chl a-specific light–response curves for gross and net photosynthetic O2 evolution of T. erythraeum IMS101.

Table S4. Values of the goodness of fit for the C-specific light–response curves for gross and net photosynthetic O2 evolution of T. erythraeum IMS101.

Table S5. The Chl a-specific photosynthetic quotients of T. erythraeum IMS101.

Fig. S1. The inorganic carbon chemistry of T. erythraeum IMS101 cultures over the light period.

Fig. S2. The N-specific light–response curves for gross O2 evolution, O2 consumption, and net photosynthesis for T. erythraeum IMS101.

Fig. S3. The Chl a-specific light–response curves for gross O2 evolution, O2 consumption, and net photosynthesis for T. erythraeum IMS101.

Fig. S4. The measured and modelled in vivo light absorption spectra for T. erythraeum IMS101.

Fig. S5. The light compensation point of T. erythraeum IMS101 growth.

Fig. S6. The relative emission spectra of the culturing and MIMS LEDs and the spectral corrected light absorption spectra of T. erythraeum IMS101.

File S1. In vivo light absorption.

File S2. Modelling the in vivo light absorption from pigment absorption spectra.

File S3. Stoichiometry and energetics of N2 fixation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

TGB was supported by a UK Natural Environment Research Council PhD studentship (NE/J500379/1 DTB).

References

- Badger MR, Palmqvist K, Yu JW. 1994. Measurement of CO2 and HCO3− fluxes in cyanobacteria and microalgae during steady-state photosynthesis. Physiologia Plantarum 90, 529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD, Long BM, Woodger FJ. 2006. The environmental plasticity and ecological genomics of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 249–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NR, Harbinson J, Kramer DM. 2007. Determining the limitations and regulation of photosynthetic energy transduction in leaves. Plant, Cell & Environment 30, 1107–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelos e Ramos J, Biswas H, Schulz KG, LaRoche J, Riebesell U. 2007. Effect of rising atmospheric carbon dioxide on the marine nitrogen fixer Trichodesmium. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 21, GB2028. [Google Scholar]

- Berman-Frank I, Lundgren P, Chen YB, Küpper H, Kolber Z, Bergman B, Falkowski P. 2001. Segregation of nitrogen fixation and oxygenic photosynthesis in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Science 294, 1534–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatman TG, Lawson T, Geider RJ. 2017. A key marine diazotroph in a changing ocean: the interacting effects of temperature, CO2 and light on the growth of Trichodesmium erythraeumIMS101. PLoS One 12, e0168796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatman TG, Mangan NM, Lawson T, Geider RJ. 2018a. Inorganic carbon and pH dependency of photosynthetic rates in Trichodesmium. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 3651–3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatman TG, Oxborough K, Gledhill M, Lawson T, Geider RJ. 2018b. An integrated response of Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 growth and photo-physiology to iron, CO2, and light intensity. Frontiers in Microbiology 9, 624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhme H. 1998. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. Trends in Plant Science 3, 346–351. [Google Scholar]

- Buick R. 2008. When did oxygenic photosynthesis evolve?Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363, 2731–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Carpenter E, Montoya J, Kustka A, Capone D. 2005. Picoplankton community structure within and outside a Trichodesmium bloom in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. Vie et Milieu 55, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Capone DG. 2005. Nitrogen fixation by Trichodesmium spp.: an important source of new nitrogen to the tropical and subtropical North Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 19, GB2024. [Google Scholar]

- Capone DG, Zehr JP, Paerl HW, Bergman B, Carpenter EJ. 1997. Trichodesmium, a globally significant marine cyanobacterium. Science 276, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter EJ, Capone DG. 1992. Nitrogen fixation in Trichodesmium blooms. In: Carpenter EJ, Capone DG, eds. Marine pelagic cyanobacteria: Trichodesmium and other diazotrophs. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Chen YB, Zehr JP, Mellon M. 1996. Growth and nitrogen fixation of the diazotrophic filamentous nonheterocystous cyanobacterium Trichodesmium Sp. IMS 101 in defined media: evidence for a circadian rhythm. Journal of Phycology 32, 916–923. [Google Scholar]

- Collos Y, Mornet F, Sciandra A, Waser N, Larson A, Harrison P. 1999. An optical method for the rapid measurement of micromolar concentrations of nitrate in marine phytoplankton cultures. Journal of Applied Phycology 11, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, McGillicuddy DJ Jr. 2006. Transatlantic abundance of the N2-fixing colonial cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Science 312, 1517–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichner MJ, Klawonn I, Wilson ST, Littmann S, Whitehouse MJ, Church MJ, Kuypers MM, Karl DM, Ploug H. 2017. Chemical microenvironments and single-cell carbon and nitrogen uptake in field-collected colonies of Trichodesmium under different pCO2. ISME Journal 11, 1305–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichner M, Kranz SA, Rost B. 2014. Combined effects of different CO2 levels and N sources on the diazotrophic cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Physiologia Plantarum 152, 316–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finzi-Hart JA, Pett-Ridge J, Weber PK, Popa R, Fallon SJ, Gunderson T, Hutcheon ID, Nealson KH, Capone DG. 2009. Fixation and fate of C and N in the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium using nanometer-scale secondary ion mass spectrometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106, 6345–6350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu FX, Warner ME, Zhang Y, Feng Y, Hutchins DA. 2007. Effects of increased temperature and CO2 on photosynthesis, growth and elemental ratios of marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus (Cyanobacteria). Journal of Phycology 43, 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia NS, Fu FX, Breene CL, Bernhardt PW, Mulholland MR, Sohm JA, Hutchins DA. 2011. Interactive effects of irradiance and CO2 on CO2 fixation and N2 fixation in the diazotroph Trichodesmium erythraeum (Cyanobacteria). Journal of Phycology 47, 1292–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geider RJ, Osborne BA. 1989. Respiration and microalgal growth: a review of the quantitative relationship between dark respiration and growth. New Phytologist 112, 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber N, Sarmiento JL. 1997. Global patterns of marine nitrogen fixation and denitrification. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 11, 235–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins DA, Fu F-X, Webb EA, Walworth N, Tagliabue A. 2013. Taxon-specific response of marine nitrogen fixers to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nature Geoscience 6, 790–795. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins D, Fu FX, Zhang Y, Warner M, Feng Y, Portune K, Bernhardt P, Mulholland M. 2007. CO2 control of Trichodesmium N2 fixation, photosynthesis, growth rates, and elemental ratios: implications for past, present, and future ocean biogeochemistry. Limnology and Oceanography 52, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins DA, Walworth NG, Webb EA, Saito MA, Moran D, McIlvin MR, Gale J, Fu FX. 2015. Irreversibly increased nitrogen fixation in Trichodesmium experimentally adapted to elevated carbon dioxide. Nature Communications 6, 8155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana TM. 1992. Relationship between photosynthetic oxygen cycling and carbon assimilation in Synechococcus WH7803 (Cyanophyta). Journal of Phycology 28, 304–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kana TM. 1993. Rapid oxygen cycling in Trichodesmium thiebautii. Limnology and Oceanography 38, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, Reinhold L. 1999. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in photosynthetic microorganisms. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 50, 539–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl D, Michaels A, Bergman B, Capone D, Carpenter E, Letelier R, Lipschultz F, Paerl H, Sigman D, Stal L. 2002. Dinitrogen fixation in the world’s oceans. Biogeochemistry 57, 47–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kranz SA, Eichner M, Rost B. 2011. Interactions between CCM and N2 fixation in Trichodesmium. Photosynthesis Research 109, 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz SA, Levitan O, Richter KU, Prásil O, Berman-Frank I, Rost B. 2010. Combined effects of CO2 and light on the N2-fixing cyanobacterium Trichodesmium MS101: physiological responses. Plant Physiology 154, 334–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz SA, Sültemeyer D, Richter KU, Rost B. 2009. Carbon acquisition in Trichodesmium: the effect of pCO2 and diurnal changes. Limnology and Oceanography 54, 548–559. [Google Scholar]

- Levitan O, Brown CM, Sudhaus S, Campbell D, LaRoche J, Berman-Frank I. 2010a. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the marine diazotroph Trichodesmium IMS101 under varying temperatures and atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Environmental Microbiology 12, 1899–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan O, Rosenberg G, Setlik I, Setlikova E, Grigel J, Klepetar J, Prasil O, Berman-Frank I. 2007. Elevated CO2 enhances nitrogen fixation and growth in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Global Change Biology 13, 531–538. [Google Scholar]

- Levitan O, Sudhaus S, LaRoche J, Berman-Frank I. 2010b. The influence of pCO2 and temperature on gene expression of carbon and nitrogen pathways in Trichodesmium IMS101. PLoS One 5, e15104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthijs H, Lubberding H. 1988. Dark respiration in cyanobacteria. In: Rogers LJ, Gallon JR, eds. Biochemistry of the algae and cyanobacteria. Proceedings of the Phytochemical Society of Europe. Oxford/New York: Clarendon Press, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy DJ. 2014. Do Trichodesmium spp. populations in the North Atlantic export most of the nitrogen they fix?Global Biogeochemical Cycles 28, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- McKew BA, Davey P, Finch SJ, Hopkins J, Lefebvre SC, Metodiev MV, Oxborough K, Raines CA, Lawson T, Geider RJ. 2013. The trade-off between the light-harvesting and photoprotective functions of fucoxanthin–chlorophyll proteins dominates light acclimation in Emiliania huxleyi (clone CCMP 1516). New Phytologist 200, 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Espie GS, Canvin DT. 1988. Active transport of inorganic carbon increases the rate of O2 photoreduction by the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Physiology 88, 6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland MR, Bronk DA, Capone DG. 2004. Dinitrogen fixation and release of ammonium and dissolved organic nitrogen by Trichodesmium IMS101. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 37, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan A, Pakrasi HB. 2001. Membrane-bound protein complexes for photosynthesis and respiration in Cyanobacteria. eLS 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Platt T, Jassby AD. 1976. The relationship between photosynthesis and light for natural assemblages of coastal marine phytoplankton. Journal of Phycology 12, 421–430. [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR, Woodger FJ, Long BM. 2008. Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating-mechanism (CCM): functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 1441–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radmer RJ, Kok B. 1976. Photoreduction of O2 primes and replaces CO2 assimilation. Plant Physiology 58, 336–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Beardall J, Giordano M. 2014. Energy costs of carbon dioxide concentrating mechanisms in aquatic organisms. Photosynthesis Research 121, 111–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J, Caldeira K, Elderfield H, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Liss P, Riebesell U, Shepherd J, Turley C, Watson A. 2005. Ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide. London: The Royal Society. [Google Scholar]

- Raven J, Falkowski P. 1999. Oceanic sinks for atmospheric CO2. Plant, Cell & Environment 22, 741–755. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie R. 2008. Universal chlorophyll equations for estimating chlorophylls a, b, c, and d and total chlorophylls in natural assemblages of photosynthetic organisms using acetone, methanol, or ethanol solvents. Photosynthetica 46, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sabine CL, Feely RA, Gruber N, et al. 2004. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. Science 305, 367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz R, Reinhold L, Kaplan A. 1995. Low activation state of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in carboxysome-defective Synechococcus mutants. Plant Physiology 108, 183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solorzano L. 1969. Determination of ammonia in natural waters by the phenol hypochlorite method. Limnology and Oceanography 14, 799–801. [Google Scholar]

- Spungin D, Berman-Frank I, Levitan O. 2014. Trichodesmium’s strategies to alleviate phosphorus limitation in the future acidified oceans. Environmental Microbiology 16, 1935–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walworth NG, Fu FX, Webb EA, Saito MA, Moran D, Mcllvin MR, Lee MD, Hutchins DA. 2016. Mechanisms of increased Trichodesmium fitness under iron and phosphorus co-limitation in the present and future ocean. Nature communications 7, 12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk CP. 1968. Movement of carbon from vegetative cells to heterocysts in Anabaena cylindrica. Journal of Bacteriology 96, 2138–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeebe RE, Wolf-Gladrow DA. 2001. CO2 in seawater: equilibrium, kinetics, isotopes. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- Zeebe RE, Wolf-Gladrow D, Jansen H. 1999. On the time required to establish chemical and isotopic equilibrium in the carbon dioxide system in seawater. Marine Chemistry 65, 135–153. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.