Abstract

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is an evolutionary conserved signaling pathway that senses intra- and extracellular nutrients, growth factors, and pathogen-associated molecular patterns to regulate the function of innate and adaptive immune cell populations. In this review, we focus on the role of the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2 in the regulation of the cellular energy metabolism of these immune cells to regulate and support immune responses. In this regard, mTORC1 and mTORC2 generally promote an anabolic response by stimulating protein synthesis, glycolysis, mitochondrial functions, and lipid synthesis to influence proliferation and survival, effector and memory responses, innate training and tolerance as well as hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and differentiation. Deactivation of mTOR restores cell homeostasis after immune activation and optimizes antigen presentation and memory T-cell generation. These findings show that the mTOR pathway integrates spatiotemporal information of the environmental and cellular energy status by regulating cellular metabolic responses to guide immune cell activation. Elucidation of the metabolic control mechanisms of immune responses will help to generate a systemic understanding of the immune system.

1. Introduction

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is an evolutionary conserved serine-threonine kinase that senses and integrates a myriad of stimuli, such as growth factors and nutrients to direct cellular decisions. Its prototypical inhibitor rapamycin was isolated in the 1970s from soil samples of Easter Island (also known as Rapa Nui) and was found to have broad anti-proliferative properties, causing its application in cancer and transplantation therapy [1]. However, we now know that the role of mTOR goes far beyond proliferation and coordinates a cell-tailored metabolic program to control many biological processes. As such, the mTOR network has gained attention in immune cell activation, where rapid adaption is a prerequisite to fuel the highly demanding metabolic needs to support effector functions such as migration, cytokine mass production, phagocytosis and finally, proliferation.

This review focuses on the role of mTOR-modulated metabolism in immune cells. We will discuss the input-dependent activation of this network, how mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2 coordinate specific metabolic adaption depending on the cell type and stimuli and how this metabolic rewiring shapes immunologic effector functions.

2. Activation of the mTOR network

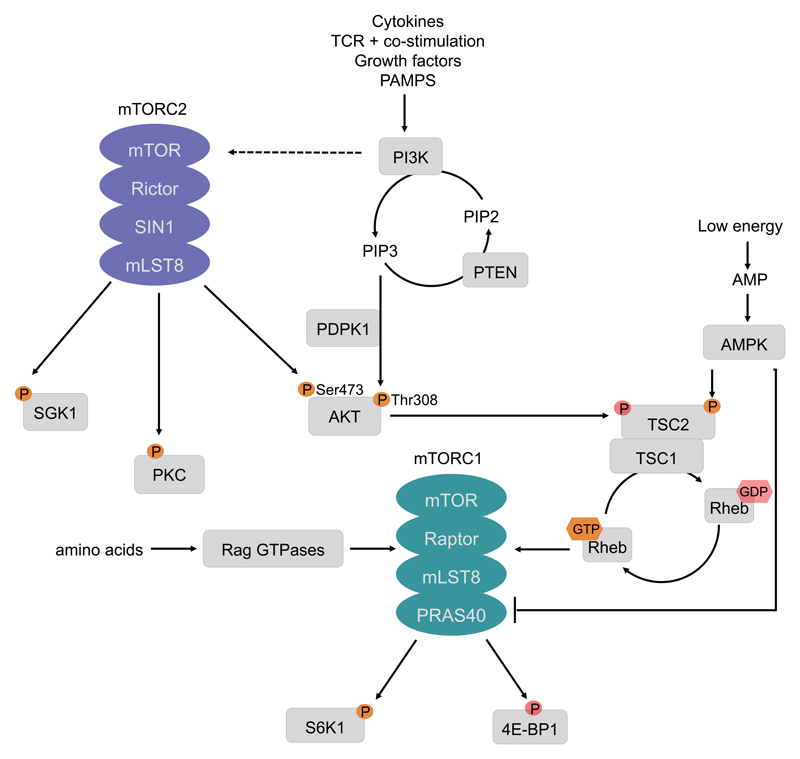

The mTORC1/mTORC2 network is activated by various classes of different extracellular ligands in the immune system (Fig. 1). In innate immune cells, the growth factors Flt3L and GM-CSF induce mTORC1 activation to regulate dendritic cell (DC) differentiation or neutrophil activation [2–4]. Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands activate mTORC1 as well as mTORC2 in neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and DCs [5–13]. Phosphoproteomic analysis recognized the mTOR network as one of the major pathways that is activated upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation in mouse macrophages [14]. The cytokine IL-4 induces mTORC1 and mTORC2 activation in macrophages [15,16], and IL-15 induces mTOR activity in NK cells [17]. During adaptive T-cell activation, stimulation of the T-cell receptor or CD28 triggers activation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 [18,19]. Typically, stimulation of the above-mentioned receptors triggers recruitment of class I phosphatidylinositol-3 kinases (PI3K) to the receptor [20] (Fig. 1). The GTPase Rab8a enables PI3Kγ recruitment to TLRs in macrophages [21]. PI3Ks then produce phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) as a second messenger to recruit and trigger activation of the serine-threonine kinase Akt via phosphorylation on threonine 308 [1]. PI3K also induces mTORC2 activity, which in turn phosphorylates Akt on serine 473 to fully activate Akt [22]. Once activated, Akt is able to phosphorylate and thereby inactivate the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) protein 2 (TSC2) [20]. TSC2, which is usually active, is a tumor suppressor that forms a heterodimeric complex with TSC1 and inhibits mTORC1. Molecularly, TSC2 is a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for the small GTPase Rheb that directly binds and activates mTORC1 [1]. Additionally, in monocytes and macrophages, p38α is able to stimulate mTORC1 in parallel to PI3K [23,24]. Furthermore, the kinase Cot/tpl2 contributes to Akt/mTORC1 activation potentially via Erk-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 [25,26]. The best known way to inhibit mTORC1 signaling is through the activation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which dephosphorylates PIP3, therefore turning off PI3K signaling [22]. Another way is the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by a high AMP/ATP ratio that causes the phosphorylation of TSC2 on serine 1387 thereby decreasing mTORC1 activity [1] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The mTOR pathway.

Cytokines, T-cell receptor (TCR) engagement and co-stimulation, growth factors but also pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) induce the activation of class I phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks). PI3K generates phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) to act as a second messenger that induces the phosphorylation of Akt on Thr308. PI3K signaling induces mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) activation, which in turn phosphorylates its downstream targets serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1), protein kinase C (PKC) and Akt on Ser473. Phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) negatively regulates PI3K signaling, by dephosphorylating PIP3. Akt phosphorylates and thereby inhibits the heterodimer tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (TSC1)/TSC2, which inhibits activation of the small GTPase Ras homologue enriched in brain (Rheb), thus releasing mTORC1 activation. However, this activation is dependent on amino acid sufficiency that is sensed by mTORC1 via the RAS-related GTP-binding protein (RAG) GTPases. During starvation periods, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) either directly inhibits mTORC1 activity or phosphorylates TSC2. In contrast to the Akt-mediated phosphorylation, AMPK supports the inhibitory function of this complex and therefore represses mTORC1 activation. The best described downstream effectors of mTORC1 are ribosomal S6 kinase1 (S6K1) and eIF4E- binding protein 1 (4E-BP1). The phosphorylation of these effectors promotes translation.

Activating phosphorylations and GTP are marked in bright orange, while inhibitory phosphorylations are displayed in faded red. Abbreviations: Raptor – regulatory-associated protein of mTOR; Rictor – Rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR; SIN1 – stress-activated MAP kinase interacting protein1; mLST8 – mammalian lethal with sec-13 protein 8.

The current model implicates that mTORC1 activation by cell surface receptors requires amino acid sufficiency, which is sensed by mTORC1 on the lysosome. Indeed, amino acid starvation inhibits IL-4-induced mTORC1 activation during M2 macrophage polarization in a dose dependent manner [27]. Regulatory T-cells (Tregs) make use of this process in a feed-forward loop to dampen T-cell activation. They induce the expression of amino acid-consuming enzymes in DCs, which deplete the surrounding microenvironment and in turn inhibit mTORC1 activation in naïve recruited T-cells to promote Treg differentiation [28]. Thus, the PI3K-AKT-mTOR network emerges as an integrator of intracellular and extracellular cues to regulate a set of basic biological processes that adapt a given effector response. mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation of a variety of downstream effectors such as 4E-binding proteins 1 and 2 (4E-BP1, 4E-BP2), S6 kinase (S6K1), or the transcription factor EB (TFEB) controls an array of basic cellular processes such as protein synthesis, cell growth, metabolism, and autophagy [1].

3. Translational regulation by mTORC1

Control of protein synthesis is a well-described function of mTORC1 [29]. For example, a massive increase in total protein synthesis occurs rapidly after TLR stimulation of macrophages and DCs [30,31]. This increased protein synthesis is vastly dependent on PI3K-mTORC1 [31,32]. mTORC1 regulates cap-dependent and independent translation by phosphorylating the translation inhibitors 4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2, which subsequently release the initiation factor eIF4E. mTORC1 is particularly effective in translation initiation of mRNAs comprising a 5′ terminal oligopyrimidine tract (5′ TOP) or a pyrimidine-rich translational element (PRTE), both encoding many ribosomal and metabolic genes [22,33]. Hence, this proteomic remodeling of the cell adjusts for the altered metabolic and functional needs [34]. On the other hand, it also allows a fast effector response after cell activation by promoting the translation of pre-existing mRNAs. Thus, adherence of macrophages rapidly induces an mTORC1-dependent de novo translation of preformed Rho-associated kinase 1 (Rock1) mRNA that induces chemotaxis and phagocytosis [35]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) are other bona fide targets that are regulated by mTOR-dependent translation [36]. Cot/tpl2 controls cap-dependent translation of TNF-α and IL-6 mRNAs through mTORC1 in TLR-stimulated macrophages [37]. The induction of type I IFN in DCs by efficient translation of interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) by mTORC1 is an additional example [38]. Activating mTORC1-dependent translation directly biases the expression of cytokines as well: low abundant mRNAs such as IL-10 are preferentially stronger expressed in comparison to high abundant proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs such as IL-12 [32]. Hence, a reduction of mTOR activity favors the translation of the more abundant proinflammatory cytokines. This is in line with data showing that translational control of mRNA expression can dampen a proinflammatory response [30]. A latent role of mTORC1 for controlling translation of these inhibitors is currently unknown but may explain some of the proinflammatory effects of mTORC1 inhibition in monocytes and DCs [39].

4. Cellular metabolism in immune cells

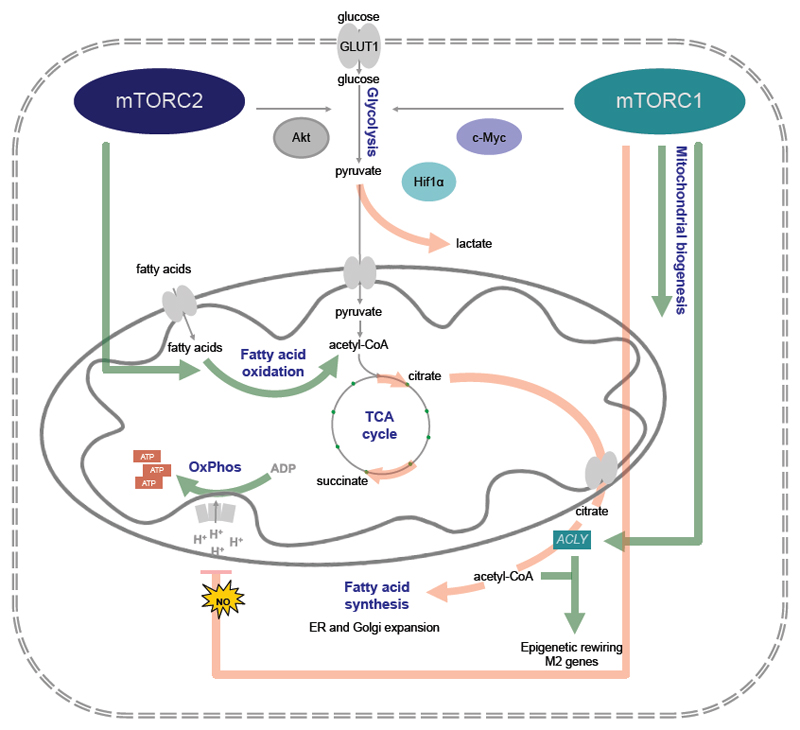

Activation of immune cells leads to massive changes in numerous signaling pathways that promote dramatic alterations in cell morphology and function; i.e. large amounts of newly expressed cytokines and chemokines are secreted, innate cells migrate to novel tissues or lymph nodes, and lymphocytes start to proliferate. These processes are apparently metabolically challenging and thus, they are supported by an adaptation of the energy metabolism to cover their metabolic needs and link it to the availability of nutrients. The central nutrients, used by eukaryotic cells to generate energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), are carbohydrates, amino acids, and fatty acids (FA) [40]. Non-proliferating cells take up the carbohydrate glucose and metabolize it in the cytoplasm to pyruvate through a process called glycolysis (Fig. 2). Pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria, where it is oxidized into acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA). Acetyl-CoA acts as fuel for the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (also known as citric acid or Krebs cycle), through which it is completely oxidized to carbon dioxide to generate ATP [40,41]. The amino acid glutamine is a second carbon source that can be converted to α-ketoglutarate (αKG) as oxidative substrate to fuel the TCA cycle [41,42]. Moreover, fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in the mitochondria generates acetyl-CoA, NADH, and FADH2 that are further used to generate ATP [43]. The TCA cycle contributes many intermediates that can act as biosynthetic substrates. For instance, mitochondrial citrate can enter the cytoplasm, where it is converted to acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate by ATP citrate lyase (ACLY). This cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA is then the substrate for fatty acids, cholesterol, and isoprenoids. Metabolic intermediates of glycolysis also feed into other biosynthetic pathways such as 3-phosphoglycerate that may be utilized in the serine biosynthesis pathway and glucose-6-phoshate that can be shuttled into the pentose phosphate pathway where it supports ribose and thus nucleotide synthesis [40,44]. When immune cells are activated and/or start to proliferate, there is increasing demand of nutrients for both energy production as well as the biosynthesis of novel molecules [45]. Proliferating/activated cells increase glucose uptake and glycolysis, but importantly do not oxidize all of the additional glucose-derived pyruvate in the TCA cycle. Instead, pyruvate is reduced to lactate in a process called aerobic glycolysis. Although this process produces only low amounts of ATP per carbon unit, it represents an important energy source that can be swiftly induced [46,47]. In contrast, mitochondrial oxidation can only be enhanced by mitochondrial biogenesis, which takes longer and may constitute a key constraint of proliferating cells [48–50]. Moreover, aerobic glycolysis may also better deal with the redox requirements during metabolic stress [48–50]. Recent data indicate that proliferating cells do not only use glycolysis as major source for the biosynthesis of proteins, but glutamine as well as other amino acids greatly contribute to the carbon mass of de novo synthesized proteins [51].

Figure 2. Metabolic control by mTOR.

In innate immune cells mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated metabolism can either support the response of inflammatory dendritic cells (DCs) and M1 polarized macrophages (red highlighted lines), as it happens for example during bacterial infection, or it can prime the immunometabolism of resident and M2 polarized macrophages (green highlighted lines). Both mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2 promote glucose uptake via the glucose transporter 1 (Glut1). mTORC1 fosters inflammatory polarization via activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) and c-Myc mediated glycolytic gene expression. It also promotes the production of toxic nitric oxide (NO), which poisons the electron transport chain. This feeds back into increased lactate production and fatty acid synthesis (FAS). In other cases, mTORC1 promotes FAS via sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), although this has not been formally shown in macrophages. FAS-derived fatty acids are utilized to rapidly expand the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This enables the cells to produce huge amounts of inflammatory cytokines. In a homeostatic setting mTORC1 also promotes glucose uptake, mitochondrial biogenesis and thus oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). IL-4 promotes mTORC1 mediated ACLY to achieve epigenetic rewiring using citrate-derived acetyl-CoA and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) via mTORC2.

5. mTOR and glycolysis

Activation of the mTOR pathway drives glycolytic metabolism by inducing two central transcription factors: HIF1α and c-Myc [52,53]. HIF1α is usually stabilized during anaerobic/hypoxic conditions and maintains cellular integrity. HIF1α can also be activated by mTORC1 upon cytokine signaling, by elevated levels of succinate, or by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [54–56]. During aerobic glycolysis, HIF1α orchestrates a transcriptional program that drives the expression of glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes such as pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 1 (PDK1). This enzyme fosters aerobic glycolysis by limiting the flow of pyruvate into the TCA cycle. This augments the tendency of pyruvate to be reduced to lactate. Therefore, HIF1α does not support mitochondrial respiration via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [57,58]. c-Myc, on the other hand, promotes both glycolytic gene expression as well as mitochondrial respiration [59,60]. Immune cells boost their glucose flux to promote cytokine production, antigen presentation, phagocytosis, ROS generation, and proliferation as detailed below.

Glycolysis and T-cells

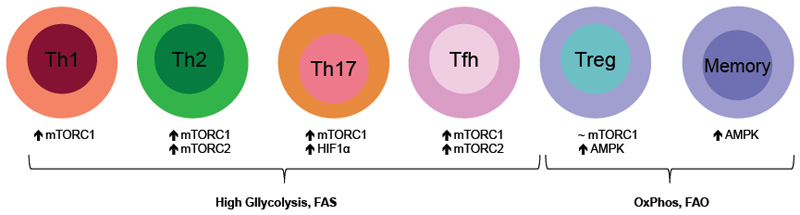

During T-cell activation, CD28-costimulation induces PI3K-Akt-dependent Glut1 expression on the cell surface, which is prevented upon ligation with the inhibitory receptors PD-1 and CTLA-4 [61–63]. HIF1α is known to prime glycolytic and cellular identities both in the adaptive and in the innate immune system. CD4+ Th17 cell development has been found to be critically dependent on the glycolytic shift induced by mTORC1-HIF1α signaling. In fact, loss of HIF1α, mTORC1 or inhibition of glycolysis skews naïve T-cells towards the Treg lineage, despite being cultured under Th17 conditions [64,65]. Peculiarly, while mTORC1-HIF1α is also required for the rather robust glycolytic reprogramming of CD8+ T-cells, this is achieved via a PI3K–Akt-independent pathway towards mTORC1 mediated by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDPK1) [54]. In line with these findings, genetic activation of mTORC1 in CD8+ T-cells (via T-cell-specific TSC2 deletion) potentiates their glycolytic phenotype and effector functions, and simultaneously impairs their transition into memory cells (Fig. 3). Curiously, loss of mTORC2 signaling enhances memory cell generation and viability, and displays an increase of both glycolytic and oxidative metabolism [66]. Thus, while mTORC2 inhibits memory cell generation in CD8+ T-cells and pulls back the metabolic demand, PDPK1-mTORC-HIF1α potentiates glucose catabolism and inflammatory properties (Fig. 2). Recently, both mTORC1 and mTORC2 were also found to be critical determinants of follicular helper T-cell (Tfh) differentiation and function [67,68]. Loss of both mTOR complexes strongly impairs the induction of glycolytic metabolism required for Tfh maturation and maintenance, but in this scenario the linearity of this pathway is more than questionable [67]. Metabolic reprogramming following T-cell activation is highly dependent on the induction of c-Myc [59]. c-Myc is strongly repressed during mTORC1 inhibition in T-cells, and is also induced in an mTORC2-dependent manner in other cell types [59,60]. Interestingly, glycolytic flux and glycolytic enzymes themselves are implicated in immunological functions. Overexpression of Glut1 in macrophages and T-cells promotes glycolysis and inflammatory properties [69,70]. Furthermore, the glycolytic metabolite phosphoenolpyruvate maintain Ca+ and NFAT signaling to promote T-cell activation [71]. The glycolytic enzyme enolase-1 controls FoxP3 splicing to stimulate induction of induced Tregs [72]. Finally, IFN-γ translation is enhanced in activated effector T-cells by engaging the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH to glycolysis [73]. In unstimulated cells, GAPDH is not committed to glycolysis and binds to AU-rich elements of the 3’ untranslated region of IFN-γ mRNA to impair its translation [73].

Figure 3. mTOR mediated metabolism shapes T-cell fate.

Naïve T-cells mainly rely on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to maintain their identity. However, upon activation T-cells induce an mTOR-dependent glycolytic metabolism and utilize fatty acid synthesis (FAS) to support clonal expansion and effector function. mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) is required for T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, Th17, follicular T helper (Tfh) cell and in very low doses for Treg differentiation, while additionally mTORC2 is indispensable for Th2 and Tfh cell fate. Memory T-cells and Tregs upregulate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-dependent fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in addition to OXPHOS to meet their metabolic demand.

Glycolysis supports macrophage and dendritic cell functions

Nearly 50 years ago Hard and colleagues provided the first evidence that inflammatory macrophages strongly induce aerobic glycolysis[74]. In fact, while in extreme polarization scenarios immune cells such as M1 macrophages or activated neutrophils clearly commit to aerobic glycolysis, this increased glucose throughput generally feeds into various metabolic pathways in order to foster effector functions. TLR stimulation induces a rigorous glycolytic phenotype in macrophages, which in extreme cases completely abolish OXPHOS [75,76]. These inflammatory macrophages express high levels of the glucose transporter Glut1 [69]. However, also the growth factors M-CSF and GM-CSF induce glucose uptake and glycolysis in macrophages [77,78]. Additionally, IL-4-induced mTORC2-Akt signaling enhances glucose utilization [27,79]. Raptor-deficient alveolar macrophages, which do not have active mTORC1 (Fig. 1), display a strong reduction in glucose uptake. TSC2-deficient macrophages, which have an incremented mTORC1, increase glucose uptake in an mTORC1-dependent manner despite a marked reduction of mTORC2-Akt activity [80,81]. This might be due to the fact that mTORC2-Akt can mediate rapid relocation of Glut1 to the cell surface, while mTORC1-mediated glucose flux probably requires a transcriptional/translational response. A prime candidate for this scenario is the transcription factor HIF1α, as its loss impairs aerobic glycolysis in macrophages in vitro. Consequently, myeloid-deficient HIF1α mice fail to develop serum transfer-induced arthritis, while deletion of VHL, the negative regulator of HIF1α, heightens inflammatory responses and lactate production [82]. TLR stimulation in DCs results in a rapid increase of glucose flux to support de novo synthesis of fatty acids via TBK1/IKKε-Akt-induced association of hexokinase 2 (HK-2) with the mitochondrial membrane [83]. In contrast to this early event, Akt-mTORC1-HIF1α signaling is crucial for a later commitment of mouse DCs to glycolysis in order to enhance their viability [77,84]. This metabolic commitment is directly related to toxic NO production that poisons the electron transport chain, whereas mTORC1 inhibition dampens NO production and thus extends the cellular lifespan [77,85,86]. Interestingly, Akt-mTORC1-HIF1α signaling is crucial to train innate memory functions [87]. Accordingly, β-glucan priming of human monocytes induces epigenetic modifications that shift metabolism from OXPHOS towards aerobic glycolysis. This alert state enables a heightened immune response to a second, unrelated stimuli one week later. Chronic activation of mTORC1 by deletion of TSC1 or TSC2 promotes glycolysis, mitochondrial respiration and lipid synthesis in DCs as well as hematopoietic stem cells and macrophages [81,88,89]. In TSC1-deficient DCs this metabolic reprogramming occurs partly via mTORC1-mediated expression of c-Myc, which is also induced in TSC2-deficient macrophages [81,88]. By using a myeloid c-Myc-deficient mouse model, it was shown that c-Myc is critical for M2 polarization. Furthermore, these mice had a markedly impaired tumor growth and a decreased expression of HIF1α, VEGF and MMP9 [90]. Finally, in LPS- and ATP-stimulated inflammatory macrophages mTORC1 has been shown to induce HK-1–stimulated glycolysis, a mechanism that is indispensable for NLRP3 inflammasome activation and thus IL-1β and IL-18 processing [91].

Collectively, a rapid increase of glucose uptake and glycolysis is a cardinal feature of immune cell activation and various key players of the mTOR pathway modulate glucose metabolism in immune cells. Nowadays it is commonly accepted that this pathway promotes glucose catabolism, but its regulation occurs on distinct levels and in a cell type-specific manner.

6. mTOR and mitochondrial biogenesis

Mitochondria are the main site of cellular energy production in the form of ATP. These cellular power plants are intimately involved in processes such as proliferation, differentiation, survival or cell death. The first link between mTORC1 signaling and elevated mitochondrial function was found in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), where genetic activation of mTORC1 (by depletion of TSC2), showed an enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism [92]. Although the exact molecular mechanisms are still not completely understood, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), together with its coregulatory peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARγ) are responsible for increased mitochondrial gene expression via the transcription factor yin-yang 1 (YY1) [92,93]. In addition, translation of mTORC1-sensitive mitochondrial proteins correlates with high ATP production and increased mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle [94]. Raptor deficiency or rapamycin treatment lead to a disruption of mitochondrial functions associated with activated stress responses. This suggests that mTORC1 activation is tightly coupled to positive mitochondrial functions [93]. Constitutive activation of mTORC1 signaling in muscle cells enhances mitochondrial respiration, whereas its inhibition induces a metabolic shift from oxidative to glycolytic activities [92–94]. On the other hand, TSC1 depletion in neurons does not affect mitochondrial biogenesis, but mitochondrial accumulation in these cells is due to reduced mitophagy [95]. Interestingly, in mice with disrupted mitochondrial function, rapamycin-mediated mTORC1 inhibition causes a metabolic shift from glycolytic into activated amino acid catabolism [96]. Therefore, mTORC1-mediated mitochondrial function differs strongly between cells and tissues, probably dependent on their energy demand, metabolic activation and proliferation status, which is also observed in immune cells as discussed below.

In comparison to mTORC1, deletion of mTORC2 signaling does not alter mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle cells, but their oxidative metabolism is markedly reduced [93,97]. Moreover, a genome-wide shRNA screen showed that mTORC2-activated cells rely on both aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to produce ATP [98]. mTORC2 is localized to the mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM) and the subsequent mTORC2-Akt-mediated calcium release at the MAM is involved in mitochondrial physiology and mitochondrial ATP turnover [99,100]. Interestingly, in brown adipose tissue precursors Rictor deletion, which inactivates mTORC2 (Fig. 1), causes a metabolic shift from a lipogenic to an oxidative state. This is in contrast to muscle and other cell types [101].

mTOR-regulated mitochondrial functions in immune cells

mTOR-mediated mitochondrial functions in various immune cells have only recently been investigated. As discussed above, TSC1 is a central regulator of T-cell homeostasis and its deficiency in mouse T-cells results in impaired mitochondrial membrane integrity and increased ROS production. This leads to activation of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway [102,103]. T-cells from T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) overcome this predicament by promoting mTORC1 suppression through activation of AMPK. This causes an increase in OXPHOS with a concomitant reduction of glycolysis which supports viability [104]. Similar as in T-cells, TSC1 depleted DCs succumb to early apoptosis after their activation. Rapamycin treatment prolongs the lifespan of GM-DCs after activation while simultaneously enhancing their activation and T-cell stimulatory capacity [77]. The underlying mechanism is attenuation of mTORC1-induced inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and consequently reduced NO production, which allows DCs to maintain their OXPHOS capacity as discussed before [77]. Curiously, TSC2-deficient macrophages display mTORC1-mediated increased mitochondrial content and OXPHOS, continuous proliferation and markedly reduced apoptosis, even during growth factor withdrawal [81]. This leads to the spontaneous development of massive granulomas by macrophages, especially in the lung and skin [81]. Additionally, in contrast to TSC1-deficient macrophages, loss of TSC2 promotes an M2-like phenotype and this polarization is also known to increase glucose uptake and to fuel OXPHOS [16,81]. The molecular reasons for these different responses are currently unclear but may stem from the observation that TSC1 and TSC2 have mTOR-independent functions [105]. mTORC2 deficiency in macrophages markedly reduces IL-4-induced OXPHOS and consequently M2 polarization [79]. It remains to be determined how these two signaling complexes exactly synergize in directing mitochondrial homeostasis and function in immune cells.

7. mTOR-dependent lipid metabolism

The central molecule in lipid metabolism is acetyl-CoA, which is the end product of FA ß-oxidation as well as the basic building block for de novo FA and cholesterol biosynthesis. For lipid catabolism, lipids are transferred into mitochondria, via carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) and 2, where FAO takes place. FAO involves the sequential removal of 2-carbon units at the ß-position of fatty acyl-CoA molecules to produce acetyl-CoA, which can continue in the TCA cycle and OXPHOS [43,106]. FAS takes place in the cytosol, beginning with the ATP-dependent carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, catalyzed by the rate-limiting enzyme acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1). The next step, catalyzed by FA synthase (FASN), is the condensation of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA to produce saturated long-chain FAs. These form more complex lipids, such as phospholipids, triglycerides or cholesterol esters. The key players in FAS are the sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) [107]. These transcription factors drive a lipid biosynthetic program by inducing the expression of genes encoding key enzymes of lipid synthesis, such as ACC1 and FASN [107,108]. Constitutive activation of Akt has not only been found to be a driver of glycolysis but also to promote sterol and lipid synthesis [109,110]. This seems to be achieved via a direct Akt-TSC-mTORC1-S6K1-SREBP signaling axis, as genetic activation of mTORC1 (by deleting either TSC1 or TSC2) is sufficient to activate these transcription factors and their downstream targets [52]. SREBPs are elevated in case of constitutive mTORC1 activation and are required for mTORC1-induced expression of FA and sterol biosynthesis genes [52]. Likewise, insulin causes an mTORC1-dependent activation of SREBP1c to promote hepatic lipogenesis [111].

In contrast to mTORC1, the role for mTORC2 in lipid homeostasis is not as well understood. In MEFs loss of Rictor does not obviously alter levels of the active form of SREBP1 [52]. However, mice with hepatic mTORC2 deficiency have smaller livers with reduced glycogen and triglyceride content and they develop glucose intolerance and hyperinsulinemia [112]. This shows that hepatic mTORC2 is impacting whole body metabolism as it senses the state of satiety and regulates glucose and lipid metabolism in the liver by acting through insulin-Akt signaling to FoxO1 and GSK3α in an mTORC1-independent manner [112]. Recently, another target of mTORC2 in lipid metabolism has been discovered. Chen et al. identified ACLY as a molecular target of mTORC2 in a breast cancer cell line showing that mTORC2, but not mTORC1, is required for ACLY-catalyzed acetyl-CoA production [113]. ACLY converts TCA-derived citrate into cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA, where it is used as substrate for FAs, cholesterol and isoprenoids [114]. Inhibition of mTORC2 or ACLY affects mitochondrial physiology, reduces cell proliferation as well as tumor growth but is cell-type specific indicating a variable involvement of mTORC2-ACLY in these processes [113].

Lipid metabolism and T-cells

The classical view of lipids is that they are structural molecules, required for membrane formation, proliferation and energy production. Recently, lipid metabolism has gained a central position as regulator in T-cell fate decision and effector function [106,108]. For example, inactivation of the SREBP pathway not only affects lipid synthesis, but inhibits CD8+ T-cell proliferation in vitro and clonal expansion during viral infection. Furthermore, SREBP deficiency hinders metabolic reprogramming towards a glycolytic phenotype, which is typical for T-cell activation. This defect in growth and proliferation is rescued by addition of exogenous cholesterol [108]. Naïve and memory T-cells are quiescent cells that do not need to grow or produce large amounts of macromolecules. They rely on OXPHOS and FAO to fulfil their energetic requirements, a metabolic profile that is associated with quiescence and long-term survival [115–117]. FAO is fundamental for the development of CD8+ T-cell memory and for the differentiation of CD4+ regulatory T-cells [106,117]. After activation, FAO becomes dispensable and T-cell metabolism shifts to FAS [108,117]. mTORC1-SREBP signaling is a crucial determinant in this initial metabolic rewiring. Consistent with the cell culture studies mentioned above, T-cell-specific Raptor deficiency or pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 causes a significant reduction of de novo lipid synthesis after activation [108,118]. T-cell activation induces protein expression of the full length and processed mature forms of SREBP1/2. While loss of Raptor does not change the mRNA levels of SREBP1 and SREBP2, it attenuates SREBP protein expression [118]. Accordingly, inhibition of mTORC1 or PI3K reduces accumulation of SREBP in the nucleus [108]. Thus, signaling through the PI3K-mTOR pathway is necessary for the induction of the lipid anabolic gene program of activated lymphocytes by modulating SREBPs through post-transcriptional mechanisms [108,118].

Lipids in innate immunity

Lipid metabolism but also lipids per se are determining innate immune cell function. For example, cholesterol renders macrophages hyperresponsive to several TLR ligands and augments membrane rigidity in case of viral infections. In addition, limiting cholesterol synthesis spontaneously induces type I IFN production, while type I IFNs themselves decrease synthesis of cholesterol but increase its import in macrophages [119]. Furthermore, the lipid composition of the membrane shapes the response of TLRs, influences endocytosis and cytokine production [114,120]. Recently, branched fatty acid esters of hydroxy fatty acids (FAHFAs), a novel class of endogenous lipids, were discovered [121]. They have anti-inflammatory properties on adipose tissue macrophages and protect against colitis, an immune-mediated disease [121]. Innate immune cells alter their lipid metabolism in order to respond properly to certain stimuli. Within minutes after TLR engagement, inflammatory DCs boost glucose consumption via PI3K-independent TBK1/IKKε-mediated Akt activation to support citrate production, which exits the TCA cycle and fuels de novo lipid biosynthesis [83]. Inhibition of FAS causes an impairment of DC activation (including secretion of the inflammatory lipid mediator prostaglandin E2). These newly synthesized lipids are critical for DC activation, as they support the expansion of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus to increase the synthesis, transport and secretion of cytokines in response to stimulation via TLRs [83]. Similarly, M1 macrophages boost FAS, whereas M2-polarized macrophages upregulate FAO [76,122]. FAO is dependent on a PI3K-mTORC2-induced glucose flux in M2 macrophages, as IL-4-induced FAO is abolished in Rictor-deficient macrophages, but rescued upon Glut1 overexpression [79]. However, a recent study established that IL-4 induces an Akt-mTORC1 dependent increase of ACLY, a critical enzyme for FAS, to promote acetyl-CoA-derived histone acetylation and M2 gene expression [27]. FAS enzymes are likewise upregulated in M2-polarized macrophages and de novo synthesized FA are at least partially used to feed back into FAO [79,123]. FAS inhibition inhibits M2 polarization and is a prerequisite for M-CSF-induced monocyte to macrophage differentiation and phagocytic capacity [79,124]. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that proliferation of tissue resident macrophages and infection-induced M2 macrophages is also depending on FAS to a certain extent.

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

mTORC1 and mTORC2 are playing central roles in immune cell metabolism and effector functions. Immune cell trafficking, cytokine production, phagocytosis, proliferation, or maintenance of tolerance requires the appropriate type of metabolic adaptation. The glycolytic flux supports cellular building block production for proliferation and cytokine expression, while the longevity of memory T-cells, Tregs and tissue resident macrophages are dependent on reliable energy production pathways such as OXPHOS and FAO. However, homeostatic proliferation of alveolar macrophages is crucially depending on mTOR-mediated glycolytic flux [80] and thus, the potential picture of an “mTOR on - activation” vs “mTOR off - dormancy” situation is too simplistic (Fig. 3). Despite the exponentially growing amount of literature regarding mTOR-mediated immunometabolism, many dots remain that need to be connected. One complication is that this pathway is regulated in a cell type- and situation-dependent manner. A lot of information regarding sequential signaling of the mTOR pathway is based on cell line experiments, but these data clearly not always apply to immune cells in vivo. For example, during mTOR-mediated metabolism in Tfh cells, mTORC1 and mTORC2 have strongly overlapping but still discrete functions and seemingly do not signal in a sequential manner [67,68]. mTOR complexes function in feedback loops, implying that downstream effectors are also likely to be involved in upstream regulation. In this regard, it has been suggested that mTORCs function primarily as mediators of cellular and organismal homeostasis and not as direct transducers of extracellular biotic and abiotic signals [125]. Therefore, the mTOR pathway cannot be viewed as a one way street, but rather as a vast interconnected roadmap – a network. While there are multiple tools to investigate the cellular role of mTORC1 signaling, immunologic functions of mTORC2 are much less understood, as there are neither specific inhibitors available, nor is a constitutive active mTORC2 model available. To properly understand this pathway, we probably have to find a way to subtly manipulate its components. This would help to get a purer picture of how we can utilize the knowledge of mTOR-depended metabolism to develop novel therapeutic approaches in immunological diseases.

Acknowledgments

T.W. is supported by grants from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant FWF-P27701-B20, the Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (P2013_A149), and the Herzfelder’sche Familienstiftung. M.L. is supported by the [DOC] Doctoral Fellowship Programme of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

References

- [1].Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell. 2017;168:960–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Haidinger M, Poglitsch M, Geyeregger R, Kasturi S, Zeyda M, Zlabinger GJ, Pulendran B, Horl WH, Saemann MD, Weichhart T. A versatile role of mammalian target of rapamycin in human dendritic cell function and differentiation. J Immunol. 2010;185:3919–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sathaliyawala T, O'Gorman WE, Greter M, Bogunovic M, Konjufca V, Hou ZE, Nolan GP, Miller MJ, Merad M, Reizis B. Mammalian target of rapamycin controls dendritic cell development downstream of Flt3 ligand signaling. Immunity. 2010;33:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lehman JA, Calvo V, Gomez-Cambronero J. Mechanism of ribosomal p70S6 kinase activation by granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in neutrophils: cooperation of a MEK-related, THR421/SER424 kinase and a rapamycin-sensitive, m-TOR-related THR389 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28130–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fukao T, Tanabe M, Terauchi Y, Ota T, Matsuda S, Asano T, Kadowaki T, Takeuchi T, Koyasu S. PI3K-mediated negative feedback regulation of IL-12 production in DCs. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:875–81. doi: 10.1038/ni825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ohtani M, Nagai S, Kondo S, Mizuno S, Nakamura K, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Matsuda S, Koyasu S. Mammalian target of rapamycin and glycogen synthase kinase 3 differentially regulate lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-12 production in dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;112:635–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Weichhart T, Costantino G, Poglitsch M, Rosner M, Zeyda M, Stuhlmeier KM, Kolbe T, Stulnig TM, Horl WH, Hengstschlager M, et al. The TSC-mTOR signaling pathway regulates the innate inflammatory response. Immunity. 2008;29:565–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Haidinger M, Hecking M, Weichhart T, Poglitsch M, Enkner W, Vonbank K, Prayer D, Geusau A, Oberbauer R, Zlabinger GJ, et al. Sirolimus in renal transplant recipients with tuberous sclerosis complex: clinical effectiveness and implications for innate immunity. Transpl Int. 2010;23:777–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Weichhart T, Haidinger M, Katholnig K, Kopecky C, Poglitsch M, Lassnig C, Rosner M, Zlabinger GJ, Hengstschlager M, Muller M, et al. Inhibition of mTOR blocks the anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids in myeloid immune cells. Blood. 2011;117:4273–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-310888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schmitz F, Heit A, Dreher S, Eisenacher K, Mages J, Haas T, Krug A, Janssen KP, Kirschning CJ, Wagner H. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) orchestrates the defense program of innate immune cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2981–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Turnquist HR, Cardinal J, Macedo C, Rosborough BR, Sumpter TL, Geller DA, Metes D, Thomson AW. mTOR and GSK-3 shape the CD4+ T-cell stimulatory and differentiation capacity of myeloid DCs after exposure to LPS. Blood. 2010;115:4758–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-251488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jiang Q, Weiss JM, Back T, Chan T, Ortaldo JR, Guichard S, Wiltrout RH. mTOR kinase inhibitor AZD8055 enhances the immunotherapeutic activity of an agonist CD40 antibody in cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4074–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lorne E, Zhao X, Zmijewski JW, Liu G, Park YJ, Tsuruta Y, Abraham E. Participation of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 in Toll-like receptor 2- and 4-induced neutrophil activation and acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:237–45. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0290OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Weintz G, Olsen JV, Fruhauf K, Niedzielska M, Amit I, Jantsch J, Mages J, Frech C, Dolken L, Mann M, et al. The phosphoproteome of toll-like receptor-activated macrophages. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:371. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhu L, Yang T, Li L, Sun L, Hou Y, Hu X, Zhang L, Tian H, Zhao Q, Peng J, et al. TSC1 controls macrophage polarization to prevent inflammatory disease. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5696. 4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Byles V, Covarrubias AJ, Ben-Sahra I, Lamming DW, Sabatini DM, Manning BD, Horng T. The TSC-mTOR pathway regulates macrophage polarization. Nat Commun. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3834. 2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Marcais A, Cherfils-Vicini J, Viant C, Degouve S, Viel S, Fenis A, Rabilloud J, Mayol K, Tavares A, Bienvenu J, et al. The metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:749–57. doi: 10.1038/ni.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Buck MD, O'Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1345–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Waickman AT, Powell JD. mTOR metabolism, and the regulation of T-cell differentiation and function. Immunol Rev. 2012;249:43–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Luo L, Wall AA, Yeo JC, Condon ND, Norwood SJ, Schoenwaelder S, Chen KW, Jackson S, Jenkins BJ, Hartland EL, et al. Rab8a interacts directly with PI3Kgamma to modulate TLR4-driven PI3K and mTOR signalling. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5407. 4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shimobayashi M, Hall MN. Making new contacts: the mTOR network in metabolism and signalling crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:155–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Katholnig K, Kaltenecker CC, Hayakawa H, Rosner M, Lassnig C, Zlabinger GJ, Gaestel M, Muller M, Hengstschlager M, Horl WH, et al. p38alpha senses environmental stress to control innate immune responses via mechanistic target of rapamycin. J Immunol. 2013;190:1519–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McGuire VA, Gray A, Monk CE, Santos SG, Lee K, Aubareda A, Crowe J, Ronkina N, Schwermann J, Batty IH, et al. Cross talk between the Akt and p38alpha pathways in macrophages downstream of Toll-like receptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:4152–65. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01691-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lopez-Pelaez M, Soria-Castro I, Bosca L, Fernandez M, Alemany S. Cot/tpl2 activity is required for TLR-induced activation of the Akt p70 S6k pathway in macrophages: Implications for NO synthase 2 expression. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1733–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Covarrubias AJ, Aksoylar HI, Yu J, Snyder NW, Worth AJ, Iyer SS, Wang J, Ben-Sahra I, Byles V, Polynne-Stapornkul T, et al. Akt-mTORC1 signaling regulates Acly to integrate metabolic input to control of macrophage activation. Elife. 2016;5:e11612. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cobbold SP, Adams E, Farquhar CA, Nolan KF, Howie D, Lui KO, Fairchild PJ, Mellor AL, Ron D, Waldmann H. Infectious tolerance via the consumption of essential amino acids and mTOR signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12055–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903919106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. mTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6416–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schott J, Reitter S, Philipp J, Haneke K, Schafer H, Stoecklin G. Translational regulation of specific mRNAs controls feedback inhibition and survival during macrophage activation. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lelouard H, Schmidt EK, Camosseto V, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Hsu HT, Pierre P. Regulation of translation is required for dendritic cell function and survival during activation. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1427–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ivanov SS, Roy CR. Pathogen signatures activate a ubiquitination pathway that modulates the function of the metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1219–28. doi: 10.1038/ni.2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jefferies HB, Reinhard C, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Rapamycin selectively represses translation of the "polypyrimidine tract" mRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4441–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jovanovic M, Rooney MS, Mertins P, Przybylski D, Chevrier N, Satija R, Rodriguez EH, Fields AP, Schwartz S, Raychowdhury R, et al. Immunogenetics. Dynamic profiling of the protein life cycle in response to pathogens. Science. 2015;347 doi: 10.1126/science.1259038. 1259038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fox R, Nhan TQ, Law GL, Morris DR, Liles WC, Schwartz SM. PSGL-1 and mTOR regulate translation of ROCK-1 and physiological functions of macrophages. EMBO J. 2007;26:505–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Silvera D, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ. Translational control in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:254–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lopez-Pelaez M, Fumagalli S, Sanz C, Herrero C, Guerra S, Fernandez M, Alemany S. Cot/tpl2-MKK1/2-Erk1/2 controls mTORC1-mediated mRNA translation in Toll-like receptor-activated macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2982–92. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-02-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Colina R, Costa-Mattioli M, Dowling RJ, Jaramillo M, Tai LH, Breitbach CJ, Martineau Y, Larsson O, Rong L, Svitkin YV, et al. Translational control of the innate immune response through IRF-7. Nature. 2008;452:323–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Katholnig K, Linke M, Pham H, Hengstschlager M, Weichhart T. Immune responses of macrophages and dendritic cells regulated by mTOR signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:927–33. doi: 10.1042/BST20130032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].DeBerardinis RJ, Cheng T. Q's next: the diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:313–24. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Abo Alrob O, Lopaschuk GD. Role of CoA and acetyl-CoA in regulating cardiac fatty acid and glucose oxidation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:1043–51. doi: 10.1042/BST20140094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yang M, Vousden KH. Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:650–62. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Cantor JR, Sabatini DM. Cancer cell metabolism: one hallmark, many faces. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:881–98. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:441–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zielinski DC, Jamshidi N, Corbett AJ, Bordbar A, Thomas A, Palsson BO. Systems biology analysis of drivers underlying hallmarks of cancer cell metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep41241. 41241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Dai Z, Shestov AA, Lai L, Locasale JW. A Flux Balance of Glucose Metabolism Clarifies the Requirements of the Warburg Effect. Biophys J. 2016;111:1088–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Vazquez A, Oltvai ZN. Macromolecular crowding explains overflow metabolism in cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep31007. 31007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hosios AM, Hecht VC, Danai LV, Johnson MO, Rathmell JC, Steinhauser ML, Manalis SR, Vander Heiden MG. Amino Acids Rather than Glucose Account for the Majority of Cell Mass in Proliferating Mammalian Cells. Dev Cell. 2016;36:540–9. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Duvel K, Yecies JL, Menon S, Raman P, Lipovsky AI, Souza AL, Triantafellow E, Ma Q, Gorski R, Cleaver S, et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell. 2010;39:171–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Finlay DK, Rosenzweig E, Sinclair LV, Feijoo-Carnero C, Hukelmann JL, Rolf J, Panteleyev AA, Okkenhaug K, Cantrell DA. PDK1 regulation of mTOR and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 integrate metabolism and migration of CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2441–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, Frezza C, Bernard NJ, Kelly B, Foley NH, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2013;496:238–42. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Movafagh S, Crook S, Vo K. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a by reactive oxygen species: new developments in an old debate. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116:696–703. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006;3:177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab. 2006;3:187–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wang R, Dillon CP, Shi LZ, Milasta S, Carter R, Finkelstein D, McCormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Chi H, Munger J, et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity. 2011;35:871–82. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Masui K, Tanaka K, Akhavan D, Babic I, Gini B, Matsutani T, Iwanami A, Liu F, Villa GR, Gu Y, et al. mTOR complex 2 controls glycolytic metabolism in glioblastoma through FoxO acetylation and upregulation of c-Myc. Cell Metab. 2013;18:726–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Frauwirth KA, Riley JL, Harris MH, Parry RV, Rathmell JC, Plas DR, Elstrom RL, June CH, Thompson CB. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity. 2002;16:769–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Parry RV, Chemnitz JM, Frauwirth KA, Lanfranco AR, Braunstein I, Kobayashi SV, Linsley PS, Thompson CB, Riley JL. CTLA-4 and PD-1 receptors inhibit T-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9543–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9543-9553.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Francisco LM, Salinas VH, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3015–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, Vogel P, Neale G, Green DR, Chi H. HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1367–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu H, Zheng Y, Bordman Z, Fu J, Kim Y, Yen HR, et al. Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;146:772–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Pollizzi KN, Patel CH, Sun IH, Oh MH, Waickman AT, Wen J, Delgoffe GM, Powell JD. mTORC1 and mTORC2 selectively regulate CD8(+) T cell differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2090–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI77746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zeng H, Cohen S, Guy C, Shrestha S, Neale G, Brown SA, Cloer C, Kishton RJ, Gao X, Youngblood B, et al. mTORC1 and mTORC2 Kinase Signaling and Glucose Metabolism Drive Follicular Helper T Cell Differentiation. Immunity. 2016;45:540–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Yang J, Lin X, Pan Y, Wang J, Chen P, Huang H, Xue HH, Gao J, Zhong XP. Critical roles of mTOR Complex 1 and 2 for T follicular helper cell differentiation and germinal center responses. Elife. 2016;5:e17936. doi: 10.7554/eLife.17936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Freemerman AJ, Johnson AR, Sacks GN, Milner JJ, Kirk EL, Troester MA, Macintyre AN, Goraksha-Hicks P, Rathmell JC, Makowski L. Metabolic reprogramming of macrophages: glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1)-mediated glucose metabolism drives a proinflammatory phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:7884–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.522037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Jacobs SR, Herman CE, Maciver NJ, Wofford JA, Wieman HL, Hammen JJ, Rathmell JC. Glucose uptake is limiting in T cell activation and requires CD28-mediated Akt-dependent and independent pathways. J Immunol. 2008;180:4476–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Ho PC, Bihuniak JD, Macintyre AN, Staron M, Liu X, Amezquita R, Tsui YC, Cui G, Micevic G, Perales JC, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell. 2015;162:1217–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].De Rosa V, Galgani M, Porcellini A, Colamatteo A, Santopaolo M, Zuchegna C, Romano A, De Simone S, Procaccini C, La Rocca C, et al. Glycolysis controls the induction of human regulatory T cells by modulating the expression of FOXP3 exon 2 splicing variants. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:1174–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB, Jr, Faubert B, Villarino AV, O'Sullivan D, Huang SC, van der Windt GJ, Blagih J, Qiu J, et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153:1239–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hard GC. Some biochemical aspects of the immune macrophage. Br J Exp Pathol. 1970;51:97–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Rodriguez-Prados JC, Traves PG, Cuenca J, Rico D, Aragones J, Martin-Sanz P, Cascante M, Bosca L. Substrate fate in activated macrophages: a comparison between innate, classic, and alternative activation. J Immunol. 2010;185:605–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Jha AK, Huang SC, Sergushichev A, Lampropoulou V, Ivanova Y, Loginicheva E, Chmielewski K, Stewart KM, Ashall J, Everts B, et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity. 2015;42:419–30. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Amiel E, Everts B, Fritz D, Beauchamp S, Ge B, Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibition extends cellular lifespan in dendritic cells by preserving mitochondrial function. J Immunol. 2014;193:2821–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Na YR, Gu GJ, Jung D, Kim YW, Na J, Woo JS, Cho JY, Youn H, Seok SH. GM-CSF Induces Inflammatory Macrophages by Regulating Glycolysis and Lipid Metabolism. J Immunol. 2016;197:4101–4109. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Huang SC, Smith AM, Everts B, Colonna M, Pearce EL, Schilling JD, Pearce EJ. Metabolic Reprogramming Mediated by the mTORC2-IRF4 Signaling Axis Is Essential for Macrophage Alternative Activation. Immunity. 2016;45:817–830. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Deng W, Yang J, Lin X, Shin J, Gao J, Zhong XP. Essential Role of mTORC1 in Self-Renewal of Murine Alveolar Macrophages. J Immunol. 2017;198:492–504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Linke M, Pham HT, Katholnig K, Schnoller T, Miller A, Demel F, Schutz B, Rosner M, Kovacic B, Sukhbaatar N, et al. Chronic signaling via the metabolic checkpoint kinase mTORC1 induces macrophage granuloma formation and marks sarcoidosis progression. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:293–302. doi: 10.1038/ni.3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Cramer T, Yamanishi Y, Clausen BE, Forster I, Pawlinski R, Mackman N, Haase VH, Jaenisch R, Corr M, Nizet V, et al. HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 2003;112:645–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Everts B, Amiel E, Huang SC, Smith AM, Chang CH, Lam WY, Redmann V, Freitas TC, Blagih J, van der Windt GJ, et al. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-IKKvarepsilon supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:323–32. doi: 10.1038/ni.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Krawczyk CM, Holowka T, Sun J, Blagih J, Amiel E, DeBerardinis RJ, Cross JR, Jung E, Thompson CB, Jones RG, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2010;115:4742–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Everts B, Amiel E, van der Windt GJ, Freitas TC, Chott R, Yarasheski KE, Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Commitment to glycolysis sustains survival of NO-producing inflammatory dendritic cells. Blood. 2012;120:1422–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-419747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Pantel A, Teixeira A, Haddad E, Wood EG, Steinman RM, Longhi MP. Direct type I IFN but not MDA5/TLR3 activation of dendritic cells is required for maturation and metabolic shift to glycolysis after poly IC stimulation. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Martens JH, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, et al. mTOR- and HIF-1alpha-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science. 2014;345 doi: 10.1126/science.1250684. 1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Wang Y, Huang G, Zeng H, Yang K, Lamb RF, Chi H. Tuberous sclerosis 1 (Tsc1)-dependent metabolic checkpoint controls development of dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4894–903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308905110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Chen C, Liu Y, Liu R, Ikenoue T, Guan KL, Liu Y, Zheng P. TSC-mTOR maintains quiescence and function of hematopoietic stem cells by repressing mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2397–408. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Pello OM, Chevre R, Laoui D, De Juan A, Lolo F, Andres-Manzano MJ, Serrano M, Van Ginderachter JA, Andres V. In vivo inhibition of c-MYC in myeloid cells impairs tumor-associated macrophage maturation and pro-tumoral activities. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Moon JS, Hisata S, Park MA, DeNicola GM, Ryter SW, Nakahira K, Choi AM. mTORC1-Induced HK1-Dependent Glycolysis Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Cell Rep. 2015;12:102–15. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [92].Cunningham JT, Rodgers JT, Arlow DH, Vazquez F, Mootha VK, Puigserver P. mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1-PGC-1alpha transcriptional complex. Nature. 2007;450:736–40. doi: 10.1038/nature06322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Bentzinger CF, Romanino K, Cloetta D, Lin S, Mascarenhas JB, Oliveri F, Xia J, Casanova E, Costa CF, Brink M, et al. Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of raptor, but not of rictor, causes metabolic changes and results in muscle dystrophy. Cell Metab. 2008;8:411–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Morita M, Gravel SP, Chenard V, Sikstrom K, Zheng L, Alain T, Gandin V, Avizonis D, Arguello M, Zakaria C, et al. mTORC1 controls mitochondrial activity and biogenesis through 4E-BP-dependent translational regulation. Cell Metab. 2013;18:698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Ebrahimi-Fakhari D, Saffari A, Wahlster L, DiNardo A, Turner D, Lewis TL, Jr, Conrad C, Rothberg JM, Lipton JO, Kolker S, et al. Impaired Mitochondrial Dynamics And Mitophagy In Neuronal Models Of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2162. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Johnson SC, Yanos ME, Kayser EB, Quintana A, Sangesland M, Castanza A, Uhde L, Hui J, Wall VZ, Gagnidze A, et al. mTOR inhibition alleviates mitochondrial disease in a mouse model of Leigh syndrome. Science. 2013;342:1524–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1244360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Risson V, Mazelin L, Roceri M, Sanchez H, Moncollin V, Corneloup C, Richard-Bulteau H, Vignaud A, Baas D, Defour A, et al. Muscle inactivation of mTOR causes metabolic and dystrophin defects leading to severe myopathy. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:859–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Colombi M, Molle KD, Benjamin D, Rattenbacher-Kiser K, Schaefer C, Betz C, Thiemeyer A, Regenass U, Hall MN, Moroni C. Genome-wide shRNA screen reveals increased mitochondrial dependence upon mTORC2 addiction. Oncogene. 2011;30:1551–65. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Betz C, Stracka D, Prescianotto-Baschong C, Frieden M, Demaurex N, Hall MN. Feature Article: mTOR complex 2-Akt signaling at mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) regulates mitochondrial physiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12526–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302455110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Singh BK, Sinha RA, Zhou J, Tripathi M, Ohba K, Wang ME, Astapova I, Ghosh S, Hollenberg AN, Gauthier K, et al. Hepatic FOXO1 Target Genes Are Co-regulated by Thyroid Hormone via RICTOR Protein Deacetylation and MTORC2-AKT Protein Inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:198–214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.668673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Hung CM, Calejman CM, Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Li H, Clish CB, Hettmer S, Wagers AJ, Guertin DA. Rictor/mTORC2 loss in the Myf5 lineage reprograms brown fat metabolism and protects mice against obesity and metabolic disease. Cell Rep. 2014;8:256–71. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].O'Brien TF, Gorentla BK, Xie D, Srivatsan S, McLeod IX, He YW, Zhong XP. Regulation of T-cell survival and mitochondrial homeostasis by TSC1. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3361–70. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Yang K, Neale G, Green DR, He W, Chi H. The tumor suppressor Tsc1 enforces quiescence of naive T cells to promote immune homeostasis and function. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:888–97. doi: 10.1038/ni.2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Kishton RJ, Barnes CE, Nichols AG, Cohen S, Gerriets VA, Siska PJ, Macintyre AN, Goraksha-Hicks P, de Cubas AA, Liu T, et al. AMPK Is Essential to Balance Glycolysis and Mitochondrial Metabolism to Control T-ALL Cell Stress and Survival. Cell Metab. 2016;23:649–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Neuman NA, Henske EP. Non-canonical functions of the tuberous sclerosis complex-Rheb signalling axis. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3:189–200. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Lochner M, Berod L, Sparwasser T. Fatty acid metabolism in the regulation of T cell function. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1125–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Kidani Y, Elsaesser H, Hock MB, Vergnes L, Williams KJ, Argus JP, Marbois BN, Komisopoulou E, Wilson EB, Osborne TF, et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins are essential for the metabolic programming of effector T cells and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:489–99. doi: 10.1038/ni.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Majumder PK, Febbo PG, Bikoff R, Berger R, Xue Q, McMahon LM, Manola J, Brugarolas J, McDonnell TJ, Golub TR, et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Porstmann T, Griffiths B, Chung YL, Delpuech O, Griffiths JR, Downward J, Schulze A. PKB/Akt induces transcription of enzymes involved in cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis via activation of SREBP. Oncogene. 2005;24:6465–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Yecies JL, Zhang HH, Menon S, Liu S, Yecies D, Lipovsky AI, Gorgun C, Kwiatkowski DJ, Hotamisligil GS, Lee CH, et al. Akt stimulates hepatic SREBP1c and lipogenesis through parallel mTORC1-dependent and independent pathways. Cell Metab. 2011;14:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Hagiwara A, Cornu M, Cybulski N, Polak P, Betz C, Trapani F, Terracciano L, Heim MH, Ruegg MA, Hall MN. Hepatic mTORC2 activates glycolysis and lipogenesis through Akt, glucokinase, and SREBP1c. Cell Metab. 2012;15:725–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Chen Y, Qian J, He Q, Zhao H, Toral-Barza L, Shi C, Zhang X, Wu J, Yu K. mTOR complex-2 stimulates acetyl-CoA and de novo lipogenesis through ATP citrate lyase in HER2/PIK3CA-hyperactive breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:25224–40. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Fritsch SD, Weichhart T. Effects of Interferons and Viruses on Metabolism. Front Immunol. 2016;7:630. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].van der Windt GJ, O'Sullivan D, Everts B, Huang SC, Buck MD, Curtis JD, Chang CH, Smith AM, Ai T, Faubert B, et al. CD8 memory T cells have a bioenergetic advantage that underlies their rapid recall ability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:14336–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221740110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Wang R, Green DR. Metabolic reprogramming and metabolic dependency in T cells. Immunol Rev. 2012;249:14–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Loftus RM, Finlay DK. Immunometabolism: Cellular Metabolism Turns Immune Regulator. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:1–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.693903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Yang K, Shrestha S, Zeng H, Karmaus PW, Neale G, Vogel P, Guertin DA, Lamb RF, Chi H. T cell exit from quiescence and differentiation into Th2 cells depend on Raptor-mTORC1-mediated metabolic reprogramming. Immunity. 2013;39:1043–56. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].York AG, Williams KJ, Argus JP, Zhou QD, Brar G, Vergnes L, Gray EE, Zhen A, Wu NC, Yamada DH, et al. Limiting Cholesterol Biosynthetic Flux Spontaneously Engages Type I IFN Signaling. Cell. 2015;163:1716–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Koberlin MS, Heinz LX, Superti-Furga G. Functional crosstalk between membrane lipids and TLR biology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2016;39:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Lee J, Moraes-Vieira PM, Castoldi A, Aryal P, Yee EU, Vickers C, Parnas O, Donaldson CJ, Saghatelian A, Kahn BB. Branched Fatty Acid Esters of Hydroxy Fatty Acids (FAHFAs) Protect against Colitis by Regulating Gut Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:22207–22217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.703835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Zhang L, Smith KL, Morel CR, Wagner RA, Greaves DR, Murray PJ, Chawla A. Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1beta attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y, O'Sullivan D, Nascimento M, Smith AM, Beatty W, Love-Gregory L, Lam WY, O'Neill CM, et al. Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:846–55. doi: 10.1038/ni.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Ecker J, Liebisch G, Englmaier M, Grandl M, Robenek H, Schmitz G. Induction of fatty acid synthesis is a key requirement for phagocytic differentiation of human monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7817–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912059107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Eltschinger S, Loewith R. TOR Complexes and the Maintenance of Cellular Homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:148–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]