Abstract

Background

HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy have a high prevalence of food insecurity in both high- and low-income settings., Women bear an inequitable burden of food insecurity due to lack of control over resources and over household food allocation decision-making. The few studies conducted on the association between food insecurity and gender among HIV-infected adults have inconclusive findings. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the pooled effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Method

We conducted an electronic, web-based search using PubMed, CINAHL, PopLine, MedNar, Embase, Cochrane library, the JBI Library, the Web of Science and Google Scholar. We included studies which reported the association between food insecurity and gender among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy whose age was greater than 18 years. The analysis was conducted using STATA 14 software. A random effects model was used to estimate the pooled effect a 95% confidence interval(CI). Forest plots were used to visualize the presence of heterogeneity. Funnel plots and Egger’s and Begg’s tests were used to check for publication bias.

Results

A total of 776 studies were identified of which seventeen studies were included in the meta-analysis, with a total of 5827 HIV infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy. We found that the gender of HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy had statistically significant effects on food insecurity. The pooled odds of developing food insecurity among female HIV infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy was 53% higher than male HIV infected adults (OR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.29, 1.83). Our analysis indicate the findings of studies conducted in the high-income countries showed weakest associations between gender and food insecurity than those conducted in low- and middle-income countries.

Conclusion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis showed statistically significant effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy in which odds of food insecurity was higher among female HIV infected adults compared to male HIV-infected adults. These findings suggest that the need to include within food and nutrition interventions for HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral treatment, culture- and context-specific gender-based policies to address the sex/gender related vulnerability to food insecurity.

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) remain a critical global health crisis[1]. Globally in 2016, there were 36.7 million people living with HIV of which 48.5% (17.8 million) were women of reproductive age (15-49years)[2]. Of the 4,500 daily new HIV infections among adults aged 15 years and older, 43% are among women and 22% are among young women (15–24years)[2].

HIV-infection and food insecurity are closely associated in both low- and high-income settings. For example, food insecurity defined as having uncertain or limited availability of nutritionally adequate or safe food or the inability to procure food in socially acceptable ways has been identified as the critical contributing factor for poor health outcome among adults living with HIV[3–6]. In addition to harming immunological and clinical outcomes in HIV-infected individuals, food insecurity has also been shown to increase the risk of HIV exposure and infection [7].

Studies show a consistently high prevalence of food insecurity among HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy, with HIV-infected women bear an inequitable burden of food insecurity in both high- and low-income settings [8–15].

Females are biologically, socioeconomically, and socio-culturally at higher risk of HIV infection than males. Gender inequity shape power relations and access to health education, and reduces the power of women to negotiate or practice safer sexual behavior which greatly increases their risk of HIV-infection in many settings [7]. Particularly, females in relationships are often more food-insecure than male partners, as a result of unequal power over economic resources and household food allocation decision-making. In addition, females often serve as caregivers and are therefore constrained in their ability to make further investments in their own skills and education, increasing their susceptibility to food insecurity[16].

Despite the fact females have increased vulnerability to food insecurity, studies conducted on the association between food insecurity and gender among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy across the world (low, middle and high-income countries), have presented controversial and inconclusive evidences. For instance, some studies have found significantly positive effect of gender on food insecurity [13, 14, 17–20], while others failed to demonstrate the effect [3, 9–11, 15, 21–26].

Estimating the pooled effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults and identify the reasons for this discrepancy in findings is important for addressing food security-related problems and for implementing focused interventions to address food security in this population. Therefore, the main objective of the current systematic review and meta-analysis is to estimate the pooled effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV—infected adult patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Our research question is: ‘‘Does gender of HIV-infected adults receiving ant-retroviral therapy determine their food security status?”.

The findings of this analysis will be helpful to policy makers and program planners in the design of appropriate interventions to improve the problems related to the association between food insecurity and gender among HIV infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy. The findings would also be useful for clinicians and future researchers in related fields.

Methods

Search strategy

This systemic review and meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the effects of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults, receiving antiretroviral therapy. Before beginning our study, we checked for the presence of the existing systematic reviews and meta-analysis on our topic using the DARE database (http://www.library.UCSF.edu) and the Cochrane library to avoid duplication. We also checked the availability of ongoing projects related to the current systematic review and meta-analysis. In addition, we searched the two Trial Registries: ICTRP and Clinical Trials.gov (searched 30 February, 2018). No previous systematic reviews or meta-analyses on the topic were found.

We searched all relevant published studies in the following major databases; PubMed, MEDLINE, Google Scholar, CINAHL, PopLine, MedNar, Embase, the Cochrane library, the JBI Library, the web of science, and African Journals Online. We also retrieved grey literature using Google and Google Scholar searches. To identify and retrieve additional articles, we also reviewed reference lists of identified studies. Unpublished studies were retrieved from the official websites of international and local organizations and universities.

The search for published studies was restricted by the age of the study participants (HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy whose age was greater than 18 years), but was not restricted by time or country. All published and unpublished articles written by the time of our search in February 30, 2018 were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

The following search terms were used: food security status, food insecurity, effect of gender, effect of gender, adults living with HIV, patients living with HIV, individuals living with HIV, HIV-infected adults, HIV-infected individuals and antiretroviral therapy separately and/or in combination.

We pre-defined search terms to allow a comprehensive search strategy that included all the important studies. All fields within records and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms) were used to help expand the search in advanced PubMed search. The following search strategies were modified for the various databases using the two important Boolean operators and search engines with initial keywords/search terms 1) (“Food security status” OR “food insecurity” AND “effect of sex” OR “effect of gender” AND “adult living with HIV” OR “Patients living with HIV” OR “individual living with HIV” AND “antiretroviral therapy”). 2) (“Food insecurity” OR “effect of sex” OR “effect of gender” AND “HIV infected adults” OR “HIV-infected patients” OR “HIV-infected individual” OR “antiretroviral therapy” AND “Ethiopia”). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was followed during the systematic review (S1 Table) [27].

Study selection and eligibility criteria

The review included articles that were conducted on the association between food insecurity and gender among HIV-infected people, receiving antiretroviral therapy globally. Participants were HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy whose age was greater than 18 years, regardless of their gender. This review considered both community and institution based studies. The outcomes considered were food insecurity and its association with gender or the effect of gender on food insecurity as measured using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS)[28, 29]. All study types that were published in the form of journal articles, master’s thesis and dissertation, that were written in English were included in the review. In addition, all studies conducted using cross sectional, case-control and cohort designs were included. We excluded studies conducted on the pediatric age group, studies with the methodological problems, interventional studies, and review articles. Retrieved studies were assessed for inclusion in the final review by reviewing their title, abstract and full-text for their agreement with our eligibility criteria.

Quality assessment and data extraction

We used reference management software (Endnote version X7.2) to combine database search results and to remove duplicate articles manually. The Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) was used for critical appraisal of studies (S2 Table) [30]. Data were extracted by two independent reviewers using a standardized data extraction format. The data extraction spreadsheet included primary author name, year of publication, country, study design, sample size, number of the subject outcome, response rate, number male with the outcome, number of females with the outcome, the total number of males and females in the study (S1 Dataset). Disagreement between reviewers in the review process were discussed with review team members until consensus was reached. Discrepancies between two independent reviewers were resolved by involving third reviewer. When access to full-text articles were not available, document authors were contacted once. If no reply was received within a month, the documents were excluded from the study.

Data analysis and synthesis

The extracted data were categorized and sorted by quality scores and entered into the computer using command window of STATA v.14. Analysis of the data were done using STATA v.14 statistical software. The logarithm and standard error of the odds ratio (OR)for each original study were generated using “generate” command in STATA. Cochrane’s Q statistic (chi-square), I2 and p-values were used to check for heterogeneity of the studies’ outcomes. The heterogeneity was considered as low, moderate or high when I2 test statistics results were 25%, 50%, and 75% respectively [31]. Forest plots were also used to visualize the presence of heterogeneity. Because we found high level of heterogeneity, we used a random effects model for analysis to estimate the Der Simonian and Laird’s pooled effect. Furthermore, to identify source of heterogeneity, meta regression was conducted and statistically significant results were declared in the presence of heterogeneity. Publication bias was checked using funnel plot of symmetry. Further, the statistical significance of publication bias was checked using Egger and Begg tests [32–34]. A p-value less than 0.05 was used to declare the presence of publication bias. We performed sensitivity analysis using a random effects model to assess the influence of a single study on the overall meta-analysis estimate.

Results

Selection and identification of studies

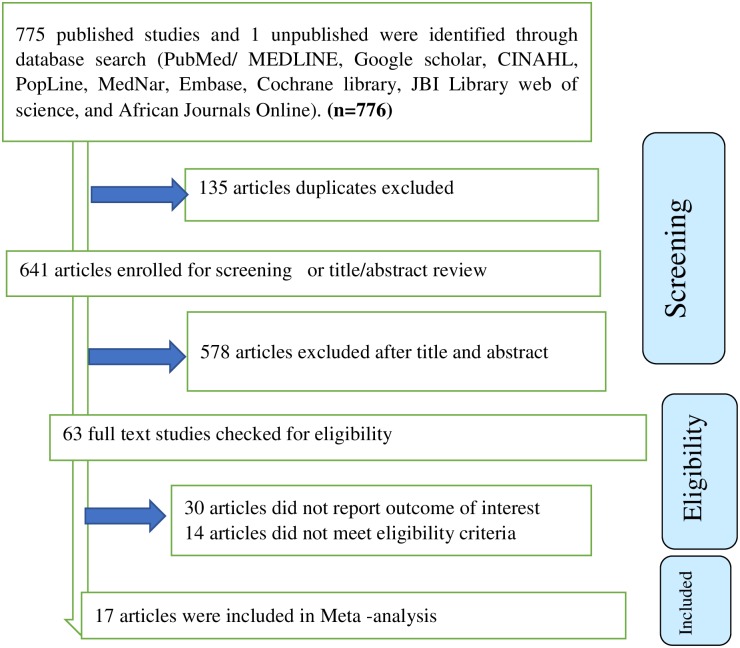

We identified a total of 776 studies (775 published and one unpublished study) that were conducted from 2009 to 2017. Of those identified, 135 duplicate studies were removed and 578 studies were excluded after reviewing of their titles and abstracts. The full text of remaining the 61 studies were assessed for eligibility and for whether they report outcome of interest. Of these, 30 studies were excluded due to lack of outcome of interest and 14 studies were excluded because they failed to meet the eligibility criteria. Of the remaining studies, the 17 that scored- seven and above on the JBI quality appraisal eligibility criteria were included in the final Meta-analysis. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram was used to guide selection process and present the systematic review overview (Fig 1).

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram of included studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected people receiving antiretroviral therapy from 2009–2017.

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 17 studies that assessed the association between food insecurity and gender among HIV infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis, with a total sample of 5827 individuals living with HIV. Eleven of these studies were cross sectional and six were prospective cohort. The range of minimum and maximum sample size ranged from104 in a study conducted in USA[3]and 796 in a study conducted in Brazil [13].

Of the total 17 included studies, four were conducted in Ethiopia[14, 17, 21, 22], five studies in the United States [3, 15, 19, 20, 25], two in Canada[9, 10], two in India[18, 23], Russia[24], Senegal[11], Uganda[26] and Brazil[13] each had one study. Six studies were conducted in low-income countries[11, 14, 17, 21, 22, 26], four studies in middle-income countries[13, 18, 23, 24] and seven studies in high-income countries[3, 9, 10, 15, 19, 20, 25].

The findings of individual studies were varied and inconclusive with the effects of gender/sex found to be significant in some studies and in- significant other. Of those studies that found significant effects of gender on food insecurity, the strongest positive association was found in the study conducted in Ethiopia[14], with an odds ratio of 4.30 (95% CI: 2.13, 8.68) and the smallest association was found in the study conducted in the United States [20], OR = 1.50 (1.01, 2,.23) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV infected people receiving antiretroviral therapy from 2009–2017.

| Study No | Authors | Year | Country | Country income level | Study design | Sample size | Number of subject with outcome | Response rate | Number male with the outcome | Number female with the outcome | Total number of male | Total number of female | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M. Asnakew[21] | 2015 | Ethiopia | Low | Cross-sectional | 385 | 260 | 97.72 | 88 | 172 | 136 | 249 | 1.22 (0.78, 1.97) |

| 2 | Gedle et al.[17] | 2015 | Ethiopia | Low | Cross-sectional | 338 | 264 | 90 | 91 | 173 | 130 | 208 | 2.12 (1.26, 3.57) |

| 3 | Belijo ZN et al[14] | 2017 | Ethiopia | Low | Cross-sectional | 394 | 77 | 100 | 10 | 67 | 134 | 260 | 4.30 (2.13, 8.68) |

| 4 | Tiyou et al[22] | 2012 | Ethiopia | Low | Cross-sectional | 319 | 201 | 100 | 86 | 115 | 144 | 175 | 1.29 (0.82, 2.04) |

| 5 | Anema et al[9] | 2013 | Canada | High | Cohort | 254 | 181 | 100 | 148 | 33 | 211 | 43 | 1.40 (0.65, 3.02) |

| 6 | Anema et al[10] | 2016 | Canada | High | Cross-sectional | 262 | 192 | 100 | 140 | 52 | 191 | 71 | 1.00 (0.54, 1.84) |

| 7 | Benzekri et al[11] | 2015 | Senegal | Low | Cross-sectional | 109 | 78 | 100 | 12 | 62 | 18 | 91 | 1.07 (0.36, 3.13) |

| 8 | Dasgupta et al[18] | 2016 | India | Middle | Cross-sectional | 173 | 75 | 92 | 33 | 42 | 96 | 77 | 2.29 (1.24, 4.24) |

| 9 | Heylen et al[23] | 2015 | India | Middle | Cohort | 367 | 58 | 100 | 38 | 20 | 239 | 128 | 0.98 (0.54, 1.77) |

| 10 | Idrisov, et al[24] | 2017 | Russia | Middle | Cohort | 310 | 164 | 88.32 | 113 | 51 | 220 | 90 | 1.24 (0.76, 2.03) |

| 11 | Kalichman et al[25] | 2013 | USA | High | Cross-sectional | 197 | 85 | 100 | 66 | 19 | 154 | 43 | 1.06 (0.53, 2.09) |

| 12 | McMahon et al[19] | 2011 | USA | High | Cohort | 592 | 375 | 100 | 239 | 136 | 416 | 176 | 2.52 (1.68, 3.77) |

| 13 | Weiser D. et al[15] | 2009 | USA | High | Cohort | 250 | 134 | 100 | 92 | 43 | 174 | 76 | 1.16 (0.68, 2.00) |

| 14 | Weiser D et al[3] | 2009 | USA | High | Cross-sectional | 104 | 26 | 100 | 15 | 11 | 66 | 40 | 1.29 (0.52, 3.18) |

| 15 | Kalichman et al[20] | 2014 | USA | High | Cross-sectional | 521 | 321 | 100 | 214 | 107 | 364 | 157 | 1.50 (1.01, 2,.23) |

| 16 | Mederios et al[13] | 2017 | Brazil | Middle | Cross-sectional | 796 | 284 | 100 | 143 | 141 | 484 | 312 | 1.97 (1.46, 2.64) |

| 17 | Tsai et al[26] | 2012 | Uganda | Low | Cohort | 456 | 340 | 100 | 93 | 247 | 132 | 324 | 1.35 (0.86, 2.12) |

The effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy

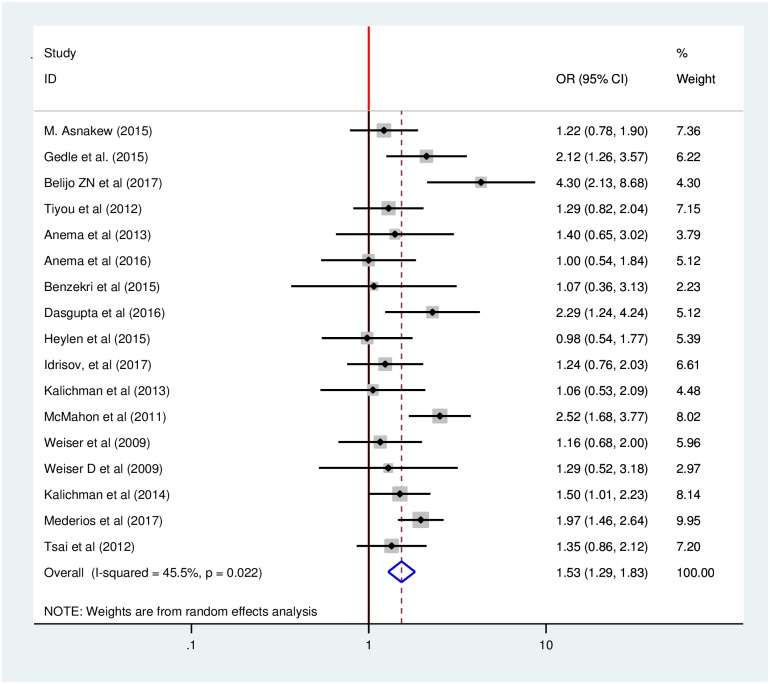

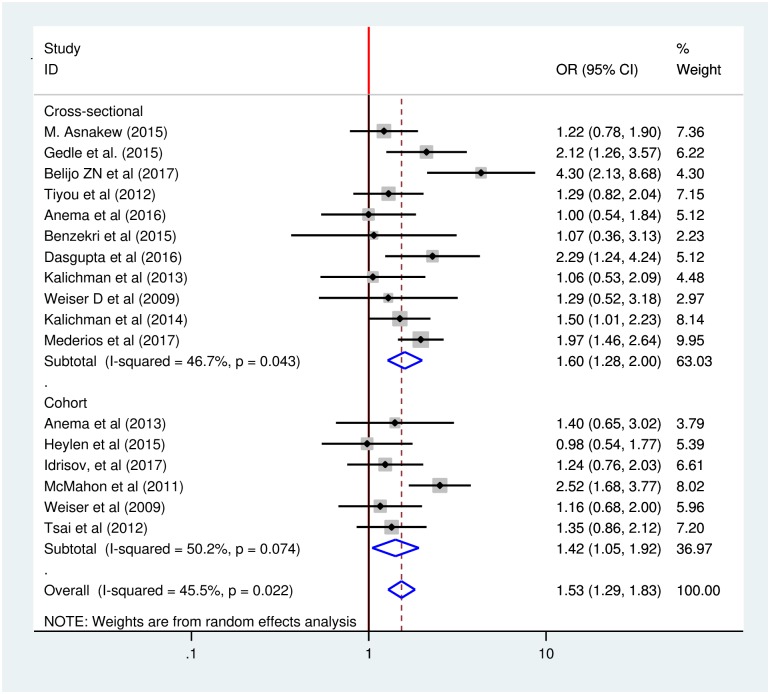

Our analysis of 17 included studies found significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 45.5%, p <0.022) which suggested that the use of a fixed effect model might lead to unreliable estimates because those model assume that all heterogeneity can be explained by the covariates. This assumption may create excessive type I errors when there is residual, or unexplained, heterogeneity. To avoid this bias, we used random effects model to estimate the pooled effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults in our 17 included studies using an inverse variance method.

Using these methods, our meta-analysis found that gender of HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy had statistically significant effects on their food security status. The odds of developing food insecurity among female HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy were 53% higher than male HIV-infected adults (OR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.29, 1.83) (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Forest plot of the pooled effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy from 2009–2017.

We further investigated the heterogeneity using different statistical techniques to identify the source of heterogeneity. A meta-regression was performed using publication year, sample size and country income level as covariates and by specifying the method for estimating the between-study variance. None of the three variables were statistically significant for explaining the presence of heterogeneity (Table 2).

Table 2. Related factors with heterogeneity of the effects of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy, 2009–2017.

| Variables | Coefficients | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Publication Year | 0.0284334 | 0.588 |

| Sample size | 0.0008173 | 0.588 |

| Low income countries | 0.0769214 | 0.751 |

| Middle income countries | -0.1118692 | 0.731 |

| High income countries | Reference |

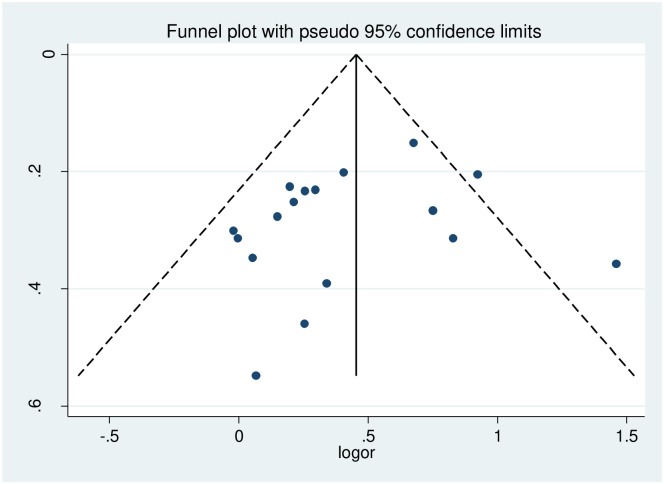

The presence of publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger and Begg statistical tests at 5% significant level. There was no statistical evidence of publication bias. The funnel plot was almost symmetry, the Begg and Egger tests were not statistically significant with p-value = 0.484 and p-value = 0.321 respectively (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Funnel plots for publication bias of effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy from 2009–2017.

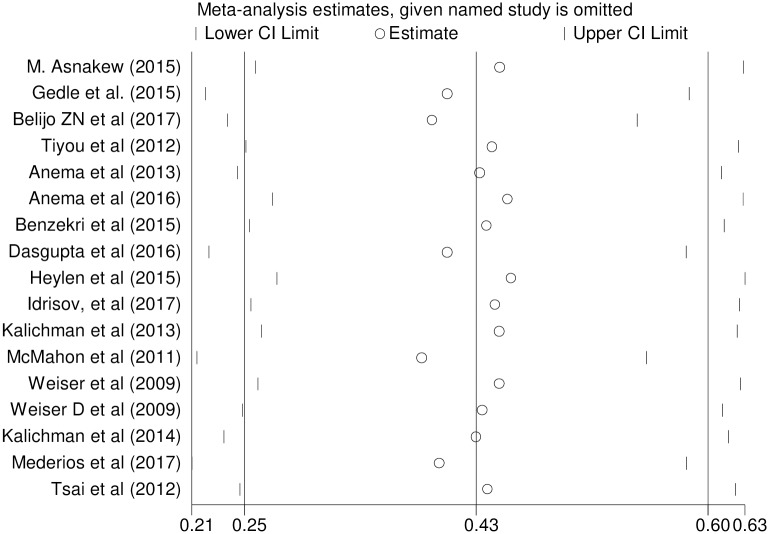

To identify the effect of single study on overall meta-analysis estimate, we performed sensitivity analysis using a random effects model. The analysis found no strong evidence for influence of single study (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Sensitivity analysis for single study influence of effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy from 2009–2017.

Sub-group analysis by study design

We performed sub-group analysis by study design to minimize the potential random variations between studies by comparing the effect of gender on food insecurity of HIV-infected adults. Our sub-group analysis indicated almost consistent significant effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults across the study designs. The analysis indicated that cohort studies had weaker associations than cross-sectional studies. The odds of developing food insecurity among female HIV-infected adults was 42% higher compared to male HIV-infected adults in cohort studies while the odds of developing food insecurity among female HIV-infected adults was 60% higher compared to male HIV-infected adults in cross sectional studies, with odds ratios of 1.42 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.92) and 1.60 (95% CI: 1.28, 2.00) respectively (Fig 5).

Fig 5. Sub-group analysis of effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy by study design from 2009–2017.

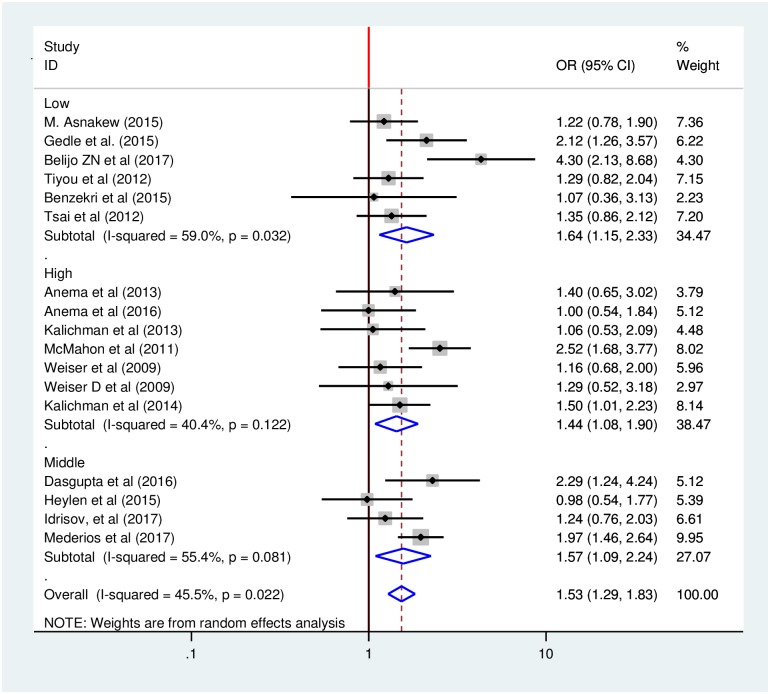

Sub-group analysis by country income level

In addition, we performed sub-group analysis by country income level to minimize the potential random variations between studies by comparing the effect of gender on food insecurity HIV-infected adults. The analysis indicated that studies conducted in high-income countries found weaker associations than those in low and middle-income countries. The odds of developing food insecurity among female HIV-infected adults was 44% higher compared to male HIV-infected adults in the studies conducted in high-income countries, with an odds ratio of 1.44 (95% CI: 1.08, 1.90). While the odds of developing food insecurity among female HIV-infected adults was 64% and 57% higher compared to male HIV-infected adults in the studies conducted in low-and middle-income countries with odds ratios of 1.64 (95% CI: 1.15, 2.33) and 1.57 (95% CI: 1.09, 2.24) respectively (Fig 6).

Fig 6. Sub-group analysis of effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy by country income level from 2009–2017.

Discussion

Our review and meta-analysis estimated the pooled effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy. The review and analysis demonstrated that the gender of HIV-infected adults has strong statistically significant effect on food insecurity. The odds of developing food insecurity among female HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy were higher than male HIV infected adults.

The significant effect of gender on food insecurity found in the current systematic review and analysis is in line with the findings of a global gap analysis systematic review on food insecurity and HIV/AIDS in which significant inequity in the experience of food insecurity by gender was found, with females being most at risk in both resource-rich and resource-limited settings[35]. This finding also consistent with the finding of a systematic review for formulating a conceptual framework for food insecurity and health in which female HIV-infected adults were most affected by food insecurity. [16]. As discussed above, these findings may be due to the fact that most females in the relationship have little power over household resource and food allocation, and that they serve as caregivers. which in turn, inhibits in their ability to make further investments in their own skills and education, increasing their susceptibility to food insecurity.

The finding of current systematic review was also consistent with the evidence of global policy review by the International Food Policy Research Institute which indicated gender inequity shapes power relations and risk[7]. The significant effect of gender on food insecurity in the current review is in line with the finding of narrative reviews and international food assistance program guidelines in which food insecurity remains a challenge for women across diverse settings[36, 37].

Our analysis indicated a relatively consistent significant effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults across study designs and country income level. We found that cohort studies had weaker associations than cross-sectional studies due to the lack of temporal relationship assurance in cohort studies.

In addition, our analysis found that the weakest associations between food insecurity and gender occurred in the studies conducted in high-income countries and the strongest in low and middle income country settings. This most likely due to a relative lack female social development particularly a lack of education in low-and middle-income settings as well as lower female power in decision-making around resource allocation.

We used comprehensive search strategies in our review systematic review and meta-analysis. We searched both published and unpublished studies through different database searches. We used random effects model to address the issues of potential variability across studies. More than one assessor was used in the quality assessment and appraisal process using JBI-MAStARI. Nevertheless, the restriction of studies published in English language limited the number of studies included in meta-analysis.

Conclusion

The systematic review and meta-analysis indicated a consistent, and statistically significant effect of gender on food insecurity among HIV-infected adults receiving anti-retroviral therapy. Being female was found to have a positive significant effect on the development of food insecurity across a range of settings; however, the association was strongest for low- and middle-income countries. The review found strong significant positive effect on the development of food insecurity among female HIV infected adults living in the low and middle income countries compared to female HIV infected adults living in high income countries. These findings suggest that policy makers, planners, and program managers in these settings should pay attention to gender dynamics in the design and implementation of HIV prevention and control program that address food insecurity. Food, nutrition and HIV intervention programs should be culture and context specific, to address the sex/gender related vulnerability to food insecurity of HIV-infected adults.

Supporting information

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DTA)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all authors of the studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- HFIAS

Household Food Insecurity Access Scale

- HIV

Human immune virus

- WHO

World Health Organization

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

No funding was obtained for this study.

References

- 1.Frega R, Duffy F, Rawat R, Grede N: Food insecurity in the context of HIV/AIDS: a framework for a new era of programming. Food and nutrition bulletin 2010, 31(4_suppl4):S292–S312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS data 2017. Geneva, Switzerland; 2017.

- 3.Weiser SD, Frongillo EA, Ragland K, Hogg RS, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR: Food insecurity is associated with incomplete HIV RNA suppression among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. Journal of general internal medicine 2009, 24(1):14–20. 10.1007/s11606-008-0824-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiser SD, Tuller DM, Frongillo EA, Senkungu J, Mukiibi N, Bangsberg DR: Food insecurity as a barrier to sustained antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda. PloS one 2010, 5(4):e10340 10.1371/journal.pone.0010340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Normen L, Chan K, Braitstein P, Anema A, Bondy G, Montaner JS et al. : Food insecurity and hunger are prevalent among HIV-positive individuals in British Columbia, Canada. The Journal of nutrition 2005, 135(4):820–825. 10.1093/jn/135.4.820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aibibula W, Cox J, Hamelin AM, McLinden T, Klein MB, Brassard P: Association Between Food Insecurity and HIV Viral Suppression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS and behavior 2017, 21(3):754–765. 10.1007/s10461-016-1605-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillespie S, Kadiyala S: HIV/AIDS and food and nutrition security: From evidence to action, vol. 7: Intl Food Policy Res Inst; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiser SD, Leiter K, Bangsberg DR, Butler LM, Percy-de Korte F, Hlanze Z et al. : Food insufficiency is associated with high-risk sexual behavior among women in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS medicine 2007, 4(10):e260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anema A, Chan K, Chen Y, Weiser S, Montaner JS, Hogg RS: Relationship between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-positive injection drug users receiving antiretroviral therapy in British Columbia, Canada. PloS one 2013, 8(5):e61277 10.1371/journal.pone.0061277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anema A, Fielden SJ, Shurgold S, Ding E, Messina J, Jones JE et al. : Association between Food Insecurity and Procurement Methods among People Living with HIV in a High Resource Setting. PloS one 2016, 11(8):e0157630 10.1371/journal.pone.0157630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benzekri NA, Sambou J, Diaw B, Sall el HI, Sall F, Niang A, et al. : High Prevalence of Severe Food Insecurity and Malnutrition among HIV-Infected Adults in Senegal, West Africa. PloS one 2015, 10(11):e0141819 10.1371/journal.pone.0141819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong SY, Fanelli TJ, Jonas A, Gweshe J, Tjituka F, Sheehan HM, et al. : Household food insecurity associated with antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV-infected patients in Windhoek, Namibia. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2014, 67(4):e115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medeiros ARC, Lima RLFCd, Medeiros LBd, Trajano FMP, Salerno AAP, Moraes RMd et al. : Moderate and severe household food insecurity in families of people living with HIV/Aids: scale validation and associated factors. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2017, 22:3353–3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mensa ZNBaM: Levels and Predictors of Food Insecurity among HIV Positive Adult Patients Taking Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia, 2016. General medicine 2017, 5(5):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Kegeles S, Ragland K, Kushel MB, Frongillo EA: Food insecurity among homeless and marginally housed individuals living with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco. AIDS and behavior 2009, 13(5):841–848. 10.1007/s10461-009-9597-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiser SD, Palar K, Hatcher AM, Young SL, Frongillo EA: Food insecurity and health: a conceptual framework In Food insecurity and public health In.: CRC Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gedle D, Kumera G, Eshete T, Feyera F and Ewunetu T: Food Insecurity and its Associated Factors among People Living with HIV/AIDS Receiving Anti-Retroviral Therapy at Butajira Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences 2015, 5(2):2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta P, Bhattacherjee S, Das DK: Food Security in Households of People Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Sydrome: A Cross-sectional Study in a Subdivision of Darjeeling District, West Bengal. Journal of preventive medicine and public health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi 2016, 49(4):240–248. 10.3961/jpmph.16.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMahon JH, Wanke CA, Elliott JH, Skinner S, Tang AM: Repeated assessments of food security predict CD4 change in the setting of antiretroviral therapy. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2011, 58(1):60–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalichman SC, Hernandez D, Cherry C, Kalichman MO, Washington C, Grebler T: Food insecurity and other poverty indicators among people living with HIV/AIDS: effects on treatment and health outcomes. Journal of community health 2014, 39(6):1133–1139. 10.1007/s10900-014-9868-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asnakew M: Food Insecurity: Prevalence and Associated Factors among Adult Individuals Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) in ART Clinics of Hosanna Town, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Open Access Library Journal 2015, 2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiyou A, Belachew T, Alemseged F, Biadgilign S: Food insecurity and associated factors among HIV-infected individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Jimma zone Southwest Ethiopia. Nutrition journal 2012, 11:51 10.1186/1475-2891-11-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heylen E, Panicker ST, Chandy S, Steward WT, Ekstrand ML: Food Insecurity and Its Relation to Psychological Well-Being Among South Indian People Living with HIV. AIDS and behavior 2015, 19(8):1548–1558. 10.1007/s10461-014-0966-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Idrisov B, Lunze K, Cheng DM, Blokhina E, Gnatienko N, Patts GJ et al. : Food Insecurity, HIV Disease Progression and Access to Care Among HIV-Infected Russians not on ART. AIDS Behav 2017, 21(12):3486–3495. 10.1007/s10461-017-1885-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, McKerney M, White D, Kalichman MO et al. : Food insecurity and antiretroviral adherence among HIV positive adults who drink alcohol. Journal of behavioral medicine 2014, 37(5):1009–1018. 10.1007/s10865-013-9536-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, Hunt PW, Muzoora C, Martin JN et al. : Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Social science & medicine (1982) 2012, 74(12):2012–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P: Reprintaepreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Physical therapy 2009, 89(9):873–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salvador Castell G, PACrez Rodrigo C, de la Cruz JN, Aranceta Bartrina J: Household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS). Nutricion hospitalaria 2015, 31(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P: Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: indicator guide. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development; 2007:34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute JB: Meta-Analysis of Statistics: Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI Mastari). Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2006, 20032007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal 2003, 327(7414):557 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple,graphical test. Bmj 1997, 315(7109):629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Begg CB, Mazumdar M: Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, Rothstein HR: A basic introduction to fixed effect and random effects models for meta-analysis. Research synthesis methods 2010, 1(2):97–111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anema A, Vogenthaler N, Frongillo EA, Kadiyala S, Weiser SD: Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS: current knowledge, gaps, and research priorities. Current HIV/AIDS reports 2009, 6(4):224–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chop E, Duggaraju A, Malley A, Burke V, Caldas S, Yeh PT, et al. : Food insecurity, sexual risk behavior, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among women living with HIV: A systematic review. Health care for women international 2017, 38(9):927–944. 10.1080/07399332.2017.1337774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frankenberger T, Spangler T, Downen J, Greenblott K, Greenaway K: Food assistance programming in the context of HIV. 2007.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DTA)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.