Abstract

Alterations in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) calcium (Ca2+) levels diminish insulin secretion and reduce β-cell survival in both major forms of diabetes. The mechanisms responsible for ER Ca2+ loss in β cells remain incompletely understood. Moreover, a specific role for either ryanodine receptor (RyR) or inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor (IP3R) dysfunction in the pathophysiology of diabetes remains largely untested. To this end, here we applied intracellular and ER Ca2+ imaging techniques in INS-1 β cells and isolated islets to determine whether diabetogenic stressors alter RyR or IP3R function. Our results revealed that the RyR is sensitive mainly to ER stress–induced dysfunction, whereas cytokine stress specifically alters IP3R activity. Consistent with this observation, pharmacological inhibition of the RyR with ryanodine and inhibition of the IP3R with xestospongin C prevented ER Ca2+ loss under ER and cytokine stress conditions, respectively. However, RyR blockade distinctly prevented β-cell death, propagation of the unfolded protein response (UPR), and dysfunctional glucose-induced Ca2+ oscillations in tunicamycin-treated INS-1 β cells and mouse islets and Akita islets. Monitoring at the single-cell level revealed that ER stress acutely increases the frequency of intracellular Ca2+ transients that depend on both ER Ca2+ leakage from the RyR and plasma membrane depolarization. Collectively, these findings indicate that RyR dysfunction shapes ER Ca2+ dynamics in β cells and regulates both UPR activation and cell death, suggesting that RyR-mediated loss of ER Ca2+ may be an early pathogenic event in diabetes.

Keywords: beta cell (B-cell); ryanodine receptor; inositol trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R); endoplasmic reticulum stress (ER stress); diabetes; calcium signaling; endoplasmic reticulum calcium; glucose-induced calcium oscillations; unfolded protein response; inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor

Introduction

Under normal conditions, the concentration of calcium (Ca2+) within the β cell endoplasmic reticulum (ER)4 is estimated to be at least three orders of magnitude higher than that of the cytosol. This steep Ca2+ concentration gradient is maintained by the balance of ER Ca2+ uptake via the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) pump, buffering by ER luminal Ca2+-binding proteins such as GRP78/BiP, calnexin, and calreticulin, and ER Ca2+ release through the ryanodine (RyR) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptors (IP3R) (1–4). ER luminal Ca2+ serves as a required cofactor for insulin production and processing, while also playing a critical role in patterning glucose-induced Ca2+ oscillations (GICOs) and phasic insulin secretion (5–7).

Although alterations in β cell ER Ca2+ homeostasis lead to diminished insulin secretion and reduced β-cell survival in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes (3, 8–10), the underlying pathways responsible for β cell ER Ca2+ loss remain incompletely understood. Reduced β cell SERCA activity and expression have been described in rodent and human models of diabetes, and SERCA2 haploinsufficiency was shown recently to result in reduced insulin secretion and decreased β-cell proliferation under high-fat diet conditions (8–11). Similarly, genetic mouse models expressing mutated forms of the RyR2, leading to increased ER Ca2+ leak, also exhibited reduced insulin secretion, whereas pharmacological antagonists of the RyR and IP3R were found to reduce β-cell death in response to thapsigargin treatment (4, 12–14).

Whereas a handful of studies suggest a potential role for RyR and IP3R dysfunction in diabetes, the specific mechanisms of how RyR and IP3R shape β cell ER Ca2+ dynamics and survival under disease conditions is unclear. To this end, we aimed to define whether RyR and IP3R were differentially modulated in response to cytokine treatment and ER stress, two conditions known to contribute to diabetes pathophysiology. Using intracellular and ER Ca2+ imaging techniques, we found impaired IP3R function in response to cytokine treatment, whereas RyR-mediated ER Ca2+ leak was preferentially induced under ER stress conditions. RyR inhibition was distinct in its ability to prevent β-cell death, potentiation of the unfolded protein response, and dysfunctional glucose-induced Ca2+ oscillations in response to tunicamycin-induced ER stress in INS-1 β cells and islets from a genetic model of β cell ER stress. Monitoring at the single cell level revealed that ER stress acutely increased the frequency of spontaneous intracellular Ca2+ transients in INS-1 cells and cadaveric human islets, which depended on both ER Ca2+ leak from the RyR as well as plasma membrane depolarization. In aggregate, these findings suggest efforts to maintain ER Ca2+ levels through stabilization of the RyR may improve β-cell function and survival, and thus represent a potential therapeutic target in diabetes.

Results

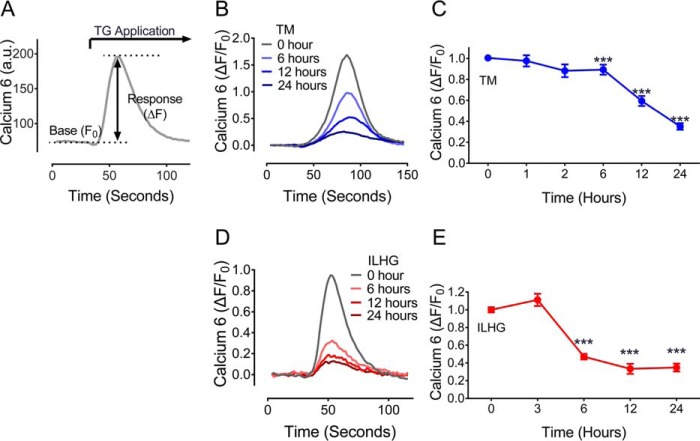

ER stress and cytokine-induced stress lead to ER Ca2+ loss

The pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes involves both β cell ER stress and cytokine-induced β-cell dysfunction (8, 15, 16). To define how these stress paradigms specifically influenced ER Ca2+ storage, INS-1 β cells were treated with 300 nm tunicamycin (TM) or 5 ng/ml interleukin 1β combined with 25 mm high glucose (ILHG) in time-course experiments. Cytosolic Ca2+ imaging was performed according to the schematic shown in Fig. 1A. Results revealed a time-dependent loss of ER Ca2+ with both TM (Fig. 1, B and C) and ILHG (Fig. 1, D and E) treatment. In both stress paradigms, significant reductions in ER Ca2+ were seen within 6 h, with further reductions observed throughout the 24-h exposure period. Reductions appeared specific to these stress paradigms as high glucose alone or mannitol (employed as an osmotic control) did not significantly impact ER Ca2+ storage (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

ER and cytokine stress result in β cell ER Ca2+ loss. A, to estimate ER calcium storage, calcium 6 was used to measure intracellular Ca2+ levels before and after application of 10 μm TG, a potent inhibitor of SERCA pump activity. B, representative traces for TG-induced Ca2+ release in INS-1 cells following treatment with 300 μm TM for indicated times. C, TM treatment led to a time-dependent reduction in ER Ca2+ levels. Results shown are from a minimum of three independent experiments for each time point. D, representative traces for TG-induced Ca2+ release in INS-1 cells following treatment with 5 ng/ml IL-1β + 25 mm glucose (ILHG) for indicated times. E, ILHG treatment led to a time-dependent reduction in ER Ca2+ levels. Results shown are from a minimum of three independent experiments for each time point. For C and E, ***, p ≤ 0.001 compared with time 0. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

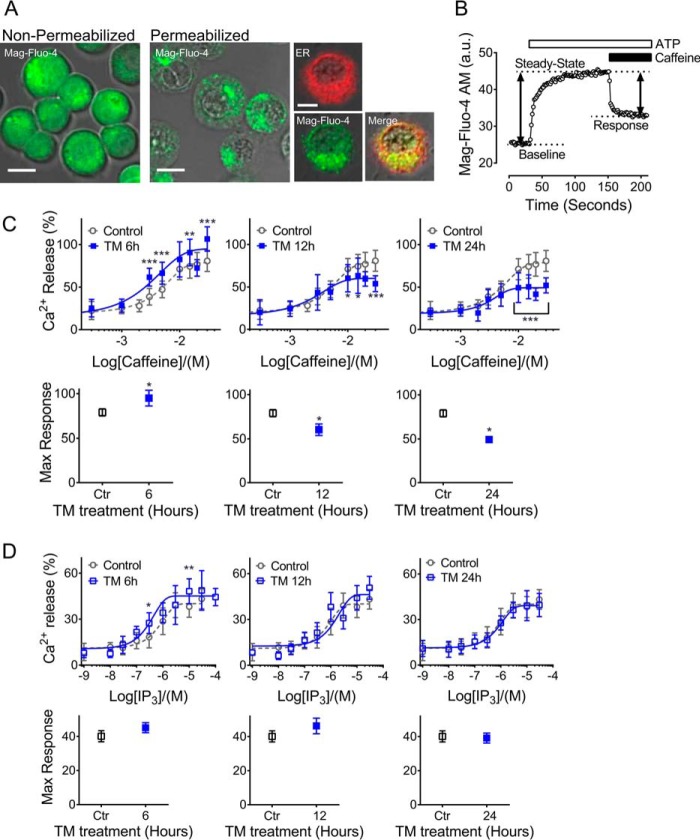

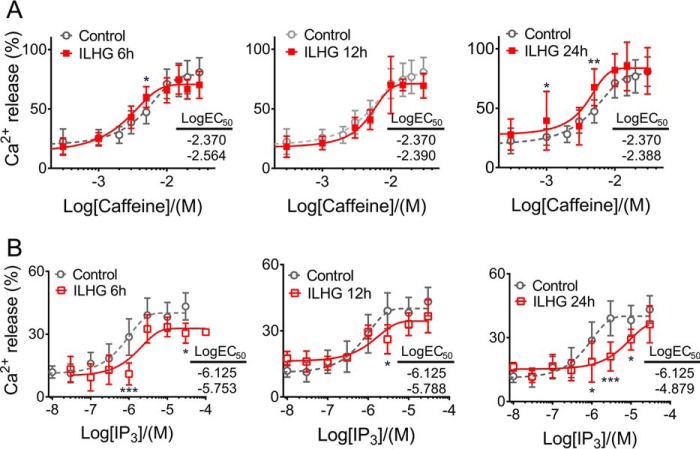

RyR and IP3R functions are differentially altered in response to ER and cytokine-induced stress

Whereas previous studies have implicated β cell SERCA2 dysfunction in diabetes, a role for either RyR or IP3R dysfunction has not been well-characterized (8–11). To test whether RyR and IP3R activity were altered in models of ER and cytokine stress, TM- and ILHG-treated INS-1 β cells were loaded with the low-affinity Ca2+ indicator Mag-Fluo-4 AM, followed by membrane permeabilization with saponin to deplete cytosolic Mag-Fluo-4. As shown in Fig. 2A, Mag-Fluo-4 AM was efficiently cleared from the cytosol, but remained sequestered within the ER, as indicated by overlap with RFP-calnexin (Fig. 2A). Next, ATP was added to achieve steady-state ER Ca2+ levels via SERCA activation. Caffeine and IP3 were added to activate RyRs and IP3Rs, respectively, and dose-response curves were generated (Fig. 2B). Our analysis revealed that TM-induced ER stress primarily altered RyR responses (Fig. 2C), whereas IP3R function was minimally impacted by TM treatment (Fig. 2D). In the short term, TM increased the maximal RyR response, whereas reductions in RyR activity were observed with chronic TM treatment (Fig. 2C). In contrast, RyR activity remained largely unaffected by ILHG (Fig. 3A). In contrast, chronic ILHG treatment reduced the EC50 of the IP3R response to agonist (Fig. 3B). Together, these results suggest that TM-induced ER stress preferentially impacted RyR function, whereas ILHG treatment preferentially impaired the IP3R response to agonist.

Figure 2.

RyR function was preferentially altered by TM-induced ER stress. A, INS-1 cells were loaded with the low-affinity Ca2+ indicator Mag-Fluo-4 AM (green). Following plasma membrane permeabilization, Mag-Fluo-4 AM was retained in the ER as demonstrated by co-localization with calnexin (red). Scale bar = 10 μm. B, to estimate RyR and IP3R activity, calcium imaging was performed according to the schematic shown in panel B. First, 1.5 mm Mg-ATP was added to establish steady-state ER Ca2+ levels. Caffeine or IP3 was applied in the indicated concentrations to generate dose-response curves of RyR and IP3R activation, respectively. Decreases in Mag-Fluo-4 AM intensity were used to calculate relative ER Ca2+ release, and GraphPad Prism Software was used to fit data from IP3R and RyR functional assays to sigmoidal dose-response curves, which were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey-Kramer post hoc test. a.u., arbitrary units. C, upper panels show the dose-response curves for RyR activation by caffeine in INS-1 cells pretreated with 300 nm TM or DMSO for 6, 12, and 24 h. Lower panels show the maximal response and 95% confidence intervals for each time point. D, upper panels show the dose-response curves for IP3R activation by IP3 in INS-1 cells pretreated with 300 nm TM for 6, 12, and 24 h. Lower panels show the maximal response and 95% confidence intervals. Data shown are from a minimum of three independent experiments for each time point and agonist concentration. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001 compared with control conditions. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

Figure 3.

Cytokine stress led to impaired IP3R function. A, dose-response curves for RyR activation by caffeine in INS-1 cells pretreated with 5 ng/mg IL + 25 mm glucose (ILHG) for 6, 12, and 24 h. B, dose-response curves for IP3R activation in INS-1 cells pretreated with ILHG for 6, 12, and 24 h. Values shown are the LogEC50 for INS-1 cells analyzed under control conditions (top) and following ILHG treatment (bottom). Data are from a minimum of three independent experiments for each time point and agonist concentration. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001 compared with control conditions. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

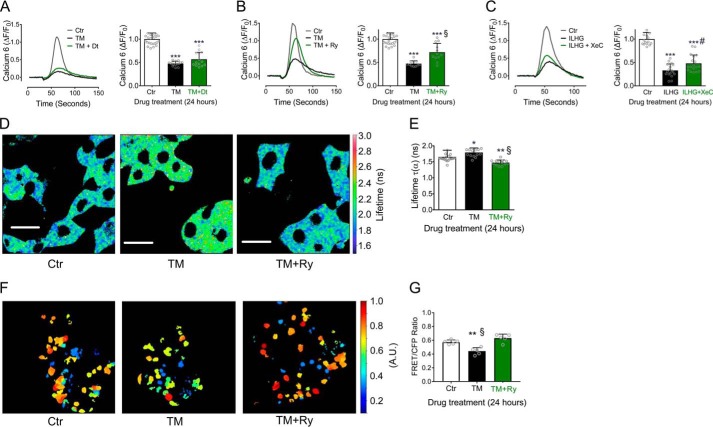

Stress-mediated ER Ca2+ loss was reduced by RyR and IP3R inhibition

To determine whether RyR or IP3R inhibition was sufficient to prevent ER Ca2+ loss under these two stress conditions, we tested the effects of RyR antagonists, dantrolene and ryanodine (Ry), and the IP3R antagonist, xestospongin C (XeC). Following TM treatment, there was no significant improvement in ER Ca2+ storage with dantrolene (Fig. 4A), whereas inhibition of RyR with Ry partially restored ER Ca2+ levels compared with TM alone (Fig. 4B). Consistent with data from functional assays shown in Figs. 2 and 3, XeC had no effect on TM-induced loss of ER Ca2+ (Fig. S2A). Similarly, Ry was unable to block ER Ca2+ loss in response to ILHG (Fig. S2B). In contrast, inhibition of IP3R with XeC partially rescued ER Ca2+ levels following ILHG treatment (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

ER Ca2+ loss was prevented by blocking the RyR under ER stress conditions and by IP3R blockade under cytokine stress conditions. A and B, INS-1 cells were co-treated with 300 nm TM and 1 μm dantrolene (Dt) (A) or with 100 μm Ry (B) for 24 h. Representative traces for TG-induced Ca2+ release (left) and quantified results (right). n = at least three times repeated per condition. C, INS-1 cells were treated with 5 ng/ml IL-1β + 25 mm glucose (ILHG) for 24 h with or without 5 μm XeC. Representative traces for the TG-induced Ca2+ release (left), and quantified results (right). n = at least three times repeated per condition. D and E, INS-1 cells were transduced with the D4ER adenovirus and co-treated 300 nm TM with or without 100 μm Ry for 24 h. FLIM was used to measure ER Ca2+ levels. Shown are representative lifetime map images with look-up table indicating donor lifetime in nanoseconds (ns) (D) and quantified results (E). n = at least three times repeated per condition; scale bar = 20 μm. F and G, islets from 8- to 10-week-old C57BL/6J mice were transduced with the D4ER adenovirus and co-treated with 300 nm TM with or without 100 μm Ry for 24 h. Z-stack images were obtained and intensities of CFP and YFP from positively transduced β cells were quantitated and presented as a ratio. F, representative maximum intensity projection images. Scale bar = 50 μm. G, quantitated FRET/CFP ratios. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001 compared with control conditions. §, p ≤ 0.001 for comparison between TM and TM + Ry in (B), (E), and (G). #, p ≤ 0.05 for comparison between ILHG and ILHG + XeC in (C). Error bars indicate ± S.D. A.U., arbitrary units.

To confirm these results, direct monitoring of ER Ca2+ levels was performed in D4ER-transduced INS-1 cells using fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM). FLIM analysis revealed an increase in the lifetime of the donor probe with TM treatment, indicating a reduction in ER Ca2+ levels. Ry treatment was able to prevent this TM-induced loss of ER Ca2+ (Fig. 4, D and E). Next, this was tested in D4ER-transduced mouse islets using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). Again, ER Ca2+ levels were reduced in TM-treated islets (detected as a decrease in FRET), whereas Ry was able to prevent this reduction (Fig. 4, F and G).

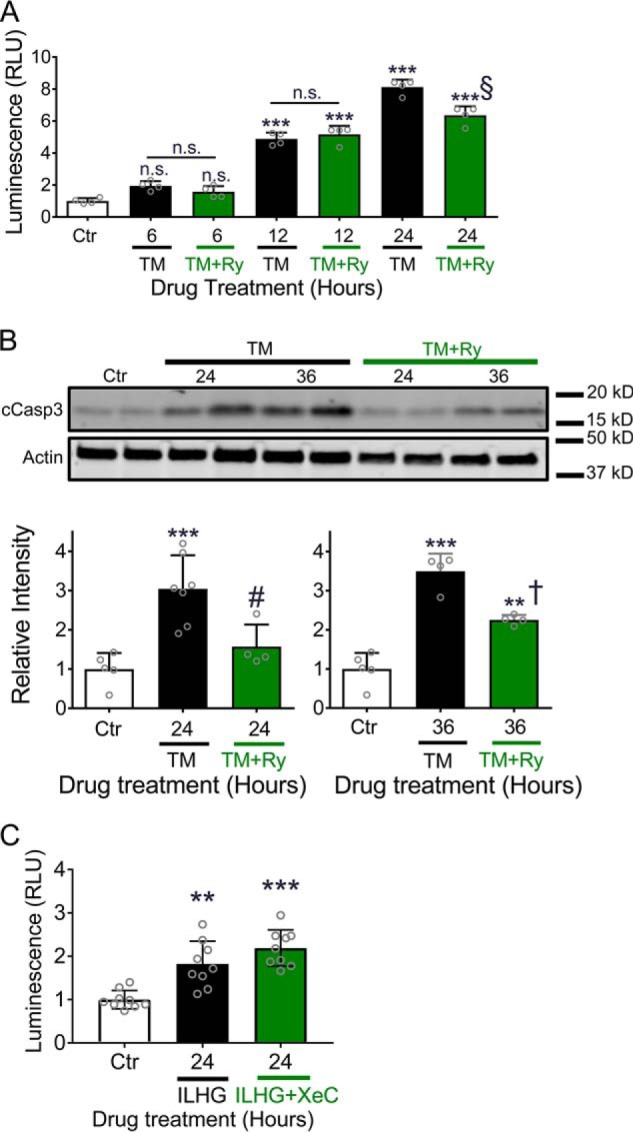

ER stress and cytokine stress are known to induce β-cell death (17), so we tested next whether modulation of ER Ca2+ loss via RyR or IP3R inhibition were sufficient to protect against β-cell death. TM treatment led to a time-dependent increase in caspase 3 and 7 activity (Fig. 5A) and expression of cleaved caspase 3 protein (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, cell death was partially abrogated by Ry co-treatment (Fig. 5, A and B). This effect on tunicamycin-induced cell death was not recapitulated by either dantrolene or XeC (Fig. S2C). Moreover, despite an observed effect to partially restore ER Ca2+ levels (Fig. 4C), XeC was unable to reduce caspase activity in response to ILHG (Fig. 5C). As expected, Ry treatment also had no effect on ILHG-induced caspase activity (Fig. S2D). In aggregate, these data revealed a unique ability of RyR inhibition to improve cell survival in response to ER stress–induced loss of ER Ca2+.

Figure 5.

Ryanodine treatment prevented TM-induced cell death. A, caspase 3/7 activity was measured in INS-1 cells after co-treating with 300 nm TM and 100 μm Ry for indicated times. n.s., no significance. B, immunoblot analysis was performed in INS-1 cells treated with 300 nm TM with or without 100 μm Ry for indicated times using antibodies against cleaved caspase-3 and actin. Quantitative protein levels are shown graphically. C, caspase 3/7 activity was measured in INS-1 cells treated with 5 ng/ml IL-1β + 25 mm glucose (ILHG) for 24 h; **, p ≤ 0.01 and ***, p ≤ 0.001 compared with control conditions. A, §, p ≤ 0.001 for the comparison between TM for 24 h and TM + Ry for 24 h. B, #, p ≤ 0.05 and †, p ≤ 0.01 for the comparisons between TM and TM + Ry for 24 and 36 h, respectively; n = at least four times repeated per condition. RLU, relative light units; n.s., no significance. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

RyR dysfunction is not mediated via reduced RyR2 expression

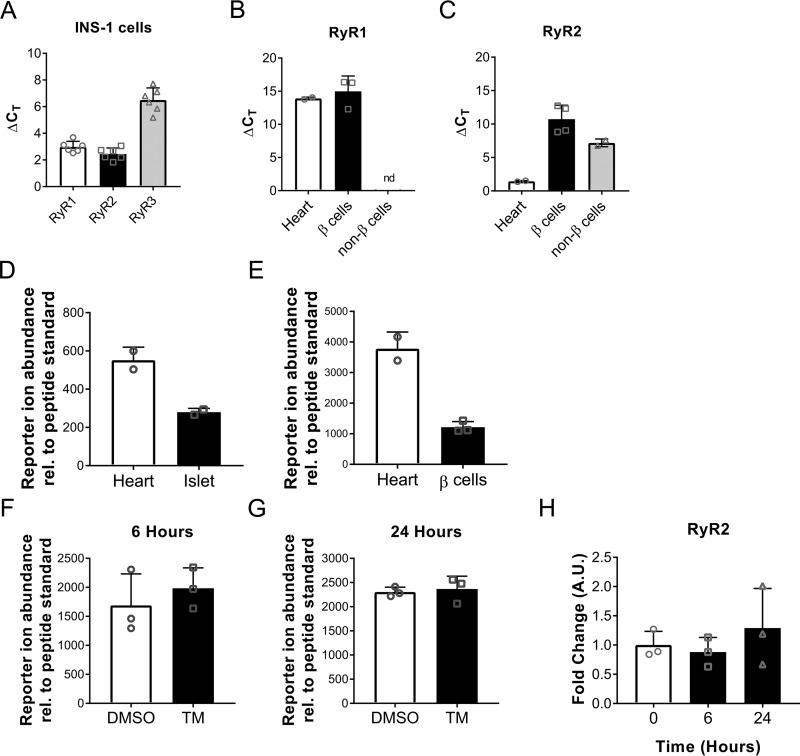

The presence of RyR in the pancreatic β cell has been debated in published studies (18, 19). To document RyR expression in our own hands, we utilized a combination of RT-qPCR in INS-1 cells and sorted mouse β cells (Fig. S3) and targeted MS analysis. Heart tissue was used as a positive control (Fig. 6, B–E). First, we confirmed RyR mRNA expression in INS-1 cells and found that RyR2 was the most highly expressed isoform in this model system as determined by lowest ΔCT values (Fig. 6A). Similarly, expression of RyR1 and RyR2 was observed in Newport Green sorted mouse β cells (Fig. S3), with RyR2 again expressed at an earlier ΔCT value compared with RyR1 (Fig. 6, B and C). Finally, to confirm RyR2 protein expression in mouse β cells, a targeted MS (T-MS) assay was developed using a peptide specific for RyR2 (891-IELGWQYGPVR-901). T-MS confirmed the presence of RyR2 protein in mouse islets (Fig. 6D) and Newport Green sorted mouse β cells (Fig. 6E). Gel electrophoresis of the PCR product and immunoblot confirming RyR expression are shown in Fig. S4. Moreover, INS-1 cells treated with TM did not exhibit reduced RyR2 expression, as shown by T-MS analysis (Fig. 6, F and G) and RT-qPCR (Fig. 6H). Taken together, these data indicate that RyRs are indeed present in rodent β cells and that TM-induced dysfunction does not result from decreased RyR2 expression.

Figure 6.

RyR expression is not altered by TM treatment. A, RyR isoform transcript levels were measured in INS-1 cells. Data expressed as ΔCT values; target CT values normalized to actin loading control CT values; n = six times repeated. B and C, RyR isoform transcript levels were measured in C57BL/6J mouse heart (positive control), sorted islet β cells, and sorted islet non-β cells. RyR1 was not detected (nd) in sorted islet non-β cells. Data expressed as ΔCT values; target CT values normalized to actin loading control CT values, n = 2–4 biological replicates from two experiments. D–G, targeted MS was used to detect the RyR2 specific peptide IELGWQYGPVR. Data expressed as experimental reporter ion abundance relative to peptide standard. D, abundance of RyR2 peptide in C57BL/6J mouse heart (positive control) and islets, n = 2 biological replicates. E, abundance of RyR2 peptide in C57BL/6J mouse heart (positive control) and sorted islet β cells, n = 2–3 biological replicates from one experiment. F and G, RyR2 peptide abundances from INS-1 cells treated with 300 nm TM for 6 and 24 h; n = 3 replicates from one experiment. H, RyR2 transcript -fold change in INS-1 cells treated with 300 nm TM for 6 and 24 h, n = 3 replicates from one experiment. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

Ryanodine and diazoxide suppressed TM-induced Ca2+ transients

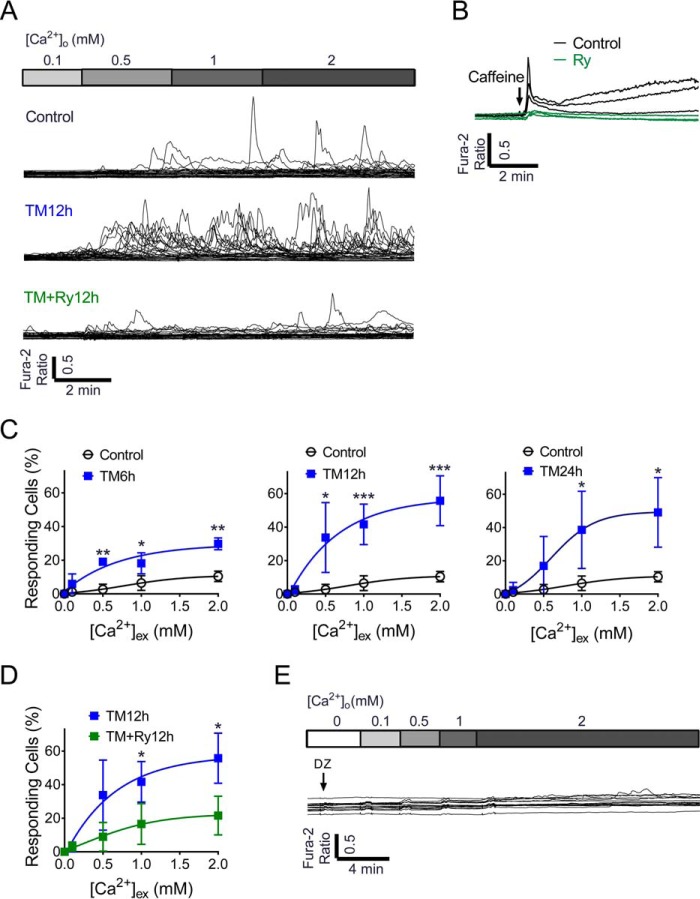

Our results thus far suggested a dominant role for RyR dysfunction under ER stress conditions, but primarily focused on bulk analysis of Ca2+ dynamics in large cell populations. Ca2+ serves as the primary ligand for the RyR, and spontaneous intracellular Ca2+ transients attributable to RyR-mediated ER Ca2+ leak have been observed in other excitable cells such as neurons and cardiac myocytes (20). However, this process has not been studied in the pancreatic β cell, under either normal or stress conditions. To identify mechanisms of ER Ca2+ release through the RyR, spontaneous Ca2+ transients were measured at the single-cell level in response to graded Ca2+ loading. By increasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration up to 2 mm, oscillating and spontaneous Ca2+ transients were induced in 10.40 ± 1.54% (S.D.) of β cells under control conditions. In response to TM-induced ER stress, the percentage of responding cells increased significantly to a maximum of 55.74 ± 6.67% after 12 h of treatment (Fig. 7, A and C). Ry co-treatment significantly decreased TM-induced Ca2+ transients (Fig. 7, A and D), indicating the ER Ca2+ leak was mediated through the RyR. In addition, the response to caffeine was inhibited in the presence of 100 μm Ry (Fig. 7B), confirming that Ry was indeed acting through inhibition of RyR-mediated Ca2+ transients.

Figure 7.

Tunicamycin-induced ER stress led to an increase in Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the β cell RyR. A, cytosolic Ca2+ transients were measured in response to extracellular Ca2+ in various concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mm Ca2+) in INS-1 cells treated under control conditions (top), following treatment with TM for 12 h (middle), or following co-treatment with TM + Ry for 12 h (bottom). Data shown are representative of 30 single cell recordings from at least three independent experiments. B, traces show cytosolic Ca2+ levels in INS-1 cells in response to caffeine treatment under control conditions and with Ry pretreatment. C, percentages (%) of responding cells in INS-1 cells treated with TM for 6 h (n = 3 times repeated), 12 h (n = 5 times repeated), and 24 h (n = 4 times repeated). D, the % of responding cells was significantly reduced by Ry co-treatment (n = 3 times repeated). E, representative trace measuring TM-induced Ca2+ transients in the presence of diazoxide. Data shown are representative of 15 single cell recordings. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001 for indicated comparisons. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

To define whether β-cell depolarization contributed to the spontaneous Ca2+ transients induced by ER stress, cells were hyperpolarized by diazoxide (Dz) to inhibit activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ (CaV) channels. In this context, TM-induced Ca2+ transients were completely suppressed (Fig. 7E), suggesting that depolarization may be an essential component of these spontaneous Ca2+ transients from the RyR under normal and ER stress conditions.

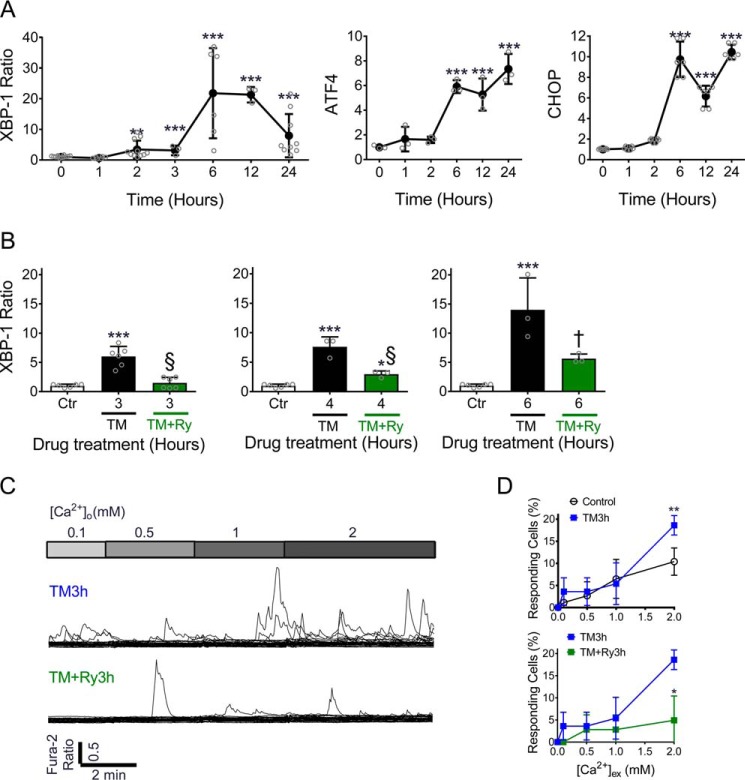

Reduced RyR-dependent ER Ca2+ leak suppressed TM-induced Ca2+ transients and delayed activation of the UPR

During ER stress, cells activate an adaptive response known as the unfolded protein response (UPR) to clear unfolded proteins and improve ER protein folding capacity (21). However, prolonged UPR activation eventually leads to apoptosis if cellular homeostasis is not restored (22, 23). Although UPR activation has been linked with ER Ca2+ loss (24), the temporal relationships and causal effects between UPR activation and ER Ca2+ loss have not been fully delineated. To address this, we first measured XBP1 mRNA splicing to validate this as an early indicator of UPR activation. An increase in the spliced to total XBP1 ratio was seen within 2 h of TM treatment and occurred prior to induction of both ATF4 and CHOP, both which increased around 6 h (Fig. 8A). Next, time-course experiments were performed to define how suppression of ER Ca2+ leak from the RyR impacted UPR activation. This analysis revealed that Ry was able to significantly delay TM-induced UPR activation, as measured by quantification of the spliced to total XBP1 ratio (Fig. 8B). To study this further, single-cell Ca2+ transients were measured again at these early time points. Intracellular Ca2+ transients were found to increase within 3 h of TM treatment. Similar to results obtained with chronic TM treatment, co-treatment with Ry was sufficient to suppress these Ca2+ transients (Fig. 8, C and D), indicating that ER Ca2+ leak is an early response to misfolded protein accumulation and occurs prior to full expression of the ER stress signaling cascade. Moreover, our results suggested that suppression of RyR-mediated Ca2+ leak was sufficient to delay UPR initiation.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of RyR-mediated ER Ca2+ leak attenuated activation of the unfolded protein response. A, INS-1 cells were treated with 300 nm TM for indicated times, and mRNA levels of the spliced/unspliced XBP-1 ratio, ATF4, and CHOP were measured by RT-PCR. B, the spliced/unspliced XBP-1 ratio was measured by RT-PCR in INS-1 cells treated with TM or TM + Ry for 3 h (left panel), 4 h (center), and 6 h (right panel). **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001 compared with time 0 or control conditions; †, p ≤ 0.01 and §, p ≤ 0.001 for comparisons between TM and TM + Ry groups. C, cytosolic Ca2+ transients were measured in response to graded Ca2+ loading in INS-1 cells treated with TM for 3 h (top) or following co-treatment with TM +Ry for 3 h (bottom). Data shown are representative of 30 single cell recordings with n = at least three replicates for each condition. D, quantification of the % of responding cells in INS-1 cells treated under controls conditions, with TM or with TM + Ry for 3 h; n = at least three replicates for each condition. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01 for comparison between indicated groups. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

Pharmacological inhibition of the RyR improved intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in TM-treated human islets and islets isolated from Akita mice

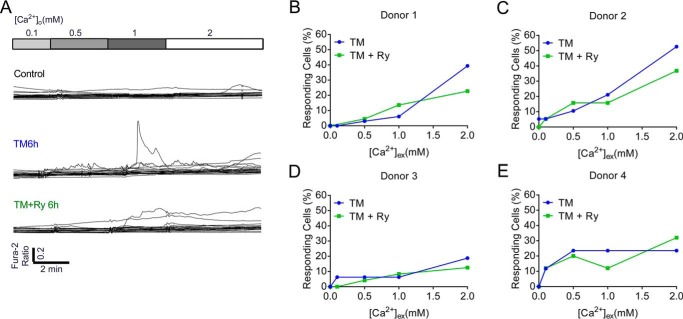

To test whether these findings could be recapitulated in a human model system, dispersed cadaveric human islets were treated with TM and cytosolic Ca2+ transients were recorded. Similar to results observed in INS-1 β cells, spontaneous Ca2+ transients were increased by TM-induced ER stress, whereas Ry co-treatment decreased TM-induced Ca2+ transients in three of four donors tested (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

TM increased RyR-mediated Ca2+ transients in human islets. A, representative data from 20 single cell calcium recordings performed in dispersed cadaveric human islets from a single biological donor analyzed under control conditions (top), following treatment with TM for 6 h (middle), and following co-treatment with TM + Ry for 6 h (bottom). B–E, the % of responding cells was quantified for each donor. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

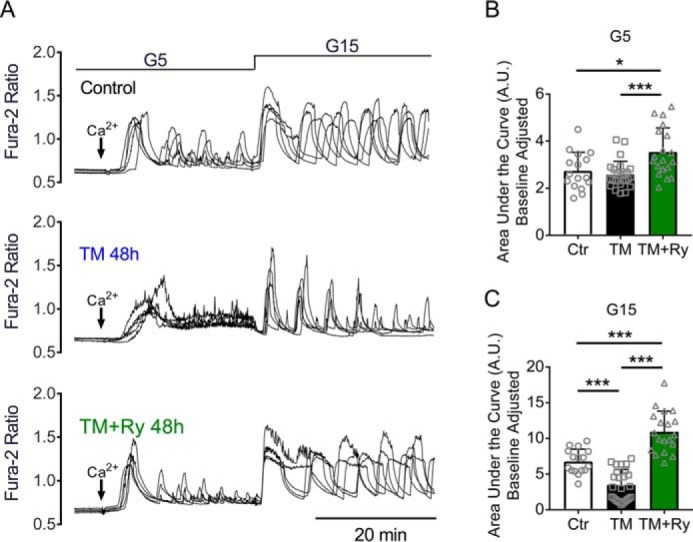

Next, we tested whether RyR inhibition would improve GICOs in TM-treated mouse islets. Islets were isolated from 8-week-old C57BL/6J mice and treated with DMSO (Ctr), TM alone, or TM + Ry for 48 h. Compared with Ctr islets, TM-treated islets exhibited altered oscillatory patterns under low (G5) and high (G15) glucose, and the area under the curve (AUC) response was significantly reduced by TM under G15 conditions (Fig. 10, A–C). Ry treatment increased the AUC of the oscillatory response compared with Ctr and TM-treated islets under both G5 and G15 glucose conditions (Fig. 10, B and C).

Figure 10.

Ryanodine treatment restored calcium oscillations in mouse islets. Glucose-stimulated calcium oscillations were measured in islets isolated from C57BL/6J mice treated with DMSO (control), TM, or TM with Ry for 48 h. A, representative recordings from five single WT islets per condition are shown. B and C, baseline corrected area under the curve was calculated from (B) 5 to 30 min (G5) and from (C) 30 to 60 min (G15). n = 16–25 islets total from two biological replicates in one experiment; *, p ≤ 0.05; ***, p ≤ 0.001 for comparisons between indicated groups. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

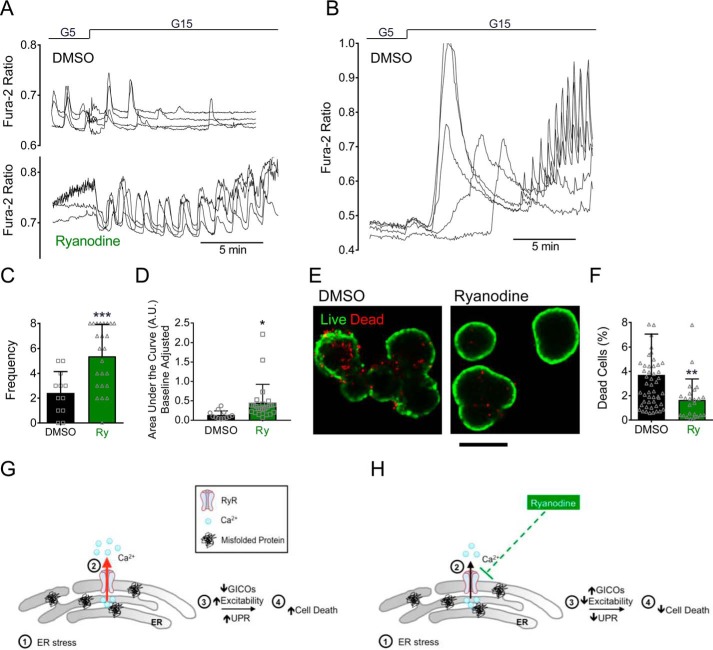

Finally, we tested whether RyR inhibition would show similar benefits in a genetic model of ER stress. To this end, islets were isolated from 6- to 8-week-old Akita and WT littermate mice. Akita mice harbor a spontaneous mutation in one allele of the INS2 gene, resulting in impaired proinsulin folding and severe ER stress (25). Fura-2 AM imaging experiments were performed in Akita islets treated with or without Ry. GICOs were markedly diminished in Akita islets under control conditions, whereas treatment with Ry improved the oscillation frequency and AUC of the glucose-induced Ca2+ responses (Fig. 11, A–D). Moreover, Ry treatment significantly decreased cell death in islets from Akita mice. (Fig. 11, E and F).

Figure 11.

Ca2+ signaling and cell death were rescued by ryanodine treatment in islets from Akita mice A and B, glucose-stimulated calcium oscillations were measured in islets isolated from Akita mice treated with DMSO or Ry for 24 h and WT littermate mice treated with DMSO for 24 h. Shown are representative recordings from four individual islets for Akita (A) and WT (B) mice. C and D, the frequency of oscillations (C) and baseline corrected area under curve for calcium responses (D) were quantified from three biological replicates per conditions. E, representative pictures of live (green) and dead (red) staining performed in Akita islets treated with DMSO or Ry for 48 h. Scale bar = 100 μm. F, quantification of the % of dead cells from three repeated experiments. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001 for comparisons between indicated groups. G and H, overall model. G, our data indicate that under ER stress conditions, RyR function is disrupted, leading to increased ER Ca2+ leak, decreased ER Ca2+ storage, and altered ER Ca2+ dynamics. As a consequence, cellular excitability and GICOs are disrupted and activation of the UPR is increased, eventually leading to cell death. H, inhibition of RyR-mediated loss of ER Ca2 leads to a partial rescue of ER Ca2+ dynamics under ER stress conditions, which improved cellular excitability and GICOs, delayed initiation of the UPR, and decreased β-cell death. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

Discussion

Reduced β cell ER Ca2+ levels have been shown to impair insulin secretion and lead to activation of cell-intrinsic stress responses including ER, mitochondrial, and oxidative stress, ultimately resulting in reduced β-cell survival (3, 5–7, 26). The RyR and IP3R are cation-selective and ligand-gated Ca2+ release channels that exist as macromolecular complexes within the ER or sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes. The goal of our study was to test whether RyR or IP3R dysfunction contributed to altered β cell ER Ca2+ storage under diabetic conditions. To this end, we applied intracellular and ER Ca2+ imaging techniques to measure activity of both receptors in response to two distinct stress paradigms. ER stress was induced chemically in INS-1 β cells, mouse islets, and cadaveric human islets using tunicamycin, a compound that inhibits protein glycosylation (8, 15, 27). In addition, aspects of our model were evaluated in islets from Akita mice, which is a genetic model of ER stress. To recapitulate cytokine-induced diabetogenic stress, INS-1 cells were treated with a combination of high glucose and IL-1β. This specific cytokine was selected because it is known to be systemically elevated in diabetes and prediabetes (28). Moreover, IL-1β has been shown to induce β-cell death, whereas IL-1β antagonism in humans yielded beneficial effects in the treatment of type 2 diabetes (29–31).

Our results revealed a preferential sensitivity of the RyR to ER stress–induced dysfunction, whereas cytokine stress was found to primarily impact IP3R activity. Pharmacological inhibition of the RyR with ryanodine and inhibition of the IP3R with xestospongin C were able to prevent ER Ca2+ loss under these respective stress conditions. However, inhibition of RyR-mediated Ca2+ loss was distinct in its ability to prevent β-cell death. Additional analysis showed that RyR inhibition also delayed initiation of the UPR, while leading to improvements in glucose-induced Ca2+ oscillations under ER stress conditions. These findings are noteworthy because several groups are actively involved in drug discovery efforts aimed at identifying small molecule RyR stabilizers (32, 33).

Others have investigated a functional role for the RyR in the pancreatic β cell under normal conditions. Several reports have shown that β cell RyRs regulate classical Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (26, 34) as well as mitochondrial ATP synthesis in response to GLP-1 stimulation (35). RyRs have also been identified on the surface of β cell dense core secretory vesicles, where they have been implicated in secretory vesicle Ca2+ release and regulation of localized Ca2+ signals responsible for granule exocytosis (36). Johnson et al. also identified RyR expression in the β cell endosomal compartment and showed the inhibition of RyR with micromolar doses of Ry decreased insulin secretion from human β cells (37). Taken together, this background suggests a role for RyR in the modulation of β-cell calcium signaling and insulin secretion under normal conditions.

Despite this existing literature, the topic of RyR expression in the pancreatic β cell has been controversial. There are three RyR isoforms encoded by three distinct genes (38). At least one group has been unable to detect RyR mRNA expression in intact islets and purified mouse β cells (5, 18). However, multiple other groups have documented RyR expression in human and rodent islets (37, 39, 40). Similar to other groups (39), we identified RyR2 as the most abundant isoform in mouse and rat β cells. To address lingering concerns regarding expression of RyR2 protein in the β cell, we developed a targeted MS assay. Using this assay, we confirmed expression of RyR2 protein in intact mouse islets, sorted mouse β cells, and INS-1 cells. Our confirmation that RyR2 is the most highly expressed isoform is notable because dantrolene was shown to have lesser effects on RyR2 activity when compared with the other isoforms (38). This could explain some of the differences we observed in the ability of dantrolene and Ry to prevent ER stress–induced ER Ca2+ loss.

Ryanodine receptor dysfunction has been documented in other disease states, including cancer-associated muscle weakness (41), Alzheimer's disease (42), and cardiac arrhythmias (43). A handful of molecular pathways have been implicated as potential contributors to β cell RyR dysfunction. Mice with a mutated form of the RyR2 leading to constitutive CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation and chronic RyR2 activation exhibited impaired glucose-induced insulin and Ca2+ responses as well as glucose intolerance (14). RyR2 mutations leading to dissociation of the interacting protein calstabin2 result in RyR gain of function and a condition known as catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) in humans (44, 45). Mice expressing two mutated forms of the RyR2 associated with CPVT were found to be glucose intolerant, whereas islets isolated from these mice exhibited decreased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and impaired mitochondrial metabolism. Intriguingly, humans with CPVT were found to have higher glucose levels and lower insulin levels during an oral glucose tolerance test compared with age- and BMI-matched controls (19).

Oxidative stress has been shown to contribute to both calstabin dissociation from the RyR as well CaMKII-mediated RyR phosphorylation (46). Indeed, alterations in calstabin and RyR association were demonstrated in islets from donors with type 2 diabetes (19). More recently, loss of sorcin, a Ca2+ sensor protein that inhibits RyR activity, was shown to lead to glucose intolerance, whereas sorcin overexpression improved glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and ER Ca2+ storage. Interestingly, palmitate-induced lipotoxicity was also shown to decrease sorcin expression in human and mouse islets (47). In aggregate, genetic models support a role for RyR activity in the maintenance of normal β-cell function. In addition, published studies hint at a potential role for impaired regulation of β cell RyR activity in models of diabetes through either impaired activity of channel-stabilizing proteins or via loss of inhibitory proteins.

Our results indicate that RyR dysfunction was uniquely induced by misfolded protein accumulation, whereas ILHG treatment had little impact on RyR function. Our data from time-course experiments further indicate that TM-induced ER Ca2+ release through RyR began even before full expression of the unfolded protein response. Thus, it is possible that RyR dysregulation could be the result of a direct interaction of misfolded or unfolded proteins with RyRs in a manner that increases channel opening. In this regard, unfolded proteins directly bind the ER luminal GRP78/BiP to initiate the UPR, although unfolded proteins have also been shown to bind and activate IRE1 (48). Consistent with this notion, prions as well as β-amyloid protein accumulation in cortical neurons induced RyR-mediated ER Ca2+ release and ER stress in neuronal tissues (49). Still another possibility is that ER stress changes the status of the ER microenvironment in a manner that favors deleterious posttranslational modifications of the RyR. TM treatment has been shown to increase ER hydrogen peroxide levels in endothelial cells (50). TM has also been shown to increase expression of the major superoxide-producing enzyme Nox4 in as little as 4 h in smooth muscle cells (51). Interestingly, Nox4 binds to RyR1 in skeletal muscle, leading to oxidization of the RyR1, dissociation of calstabin 1, and persistence of RyR1 in the open confirmation state (41). The differential impact of TM and HG + IL-1β on the oxidative status of the β cell ER will need to be tested in future studies. However, we favor a model of impaired RyR2 activity rather than a change in RyR2 expression as our analysis did not uncover alterations in RyR2 protein levels in response to TM treatment.

Finally, to document the mode of ER stress–mediated RyR dysfunction, we measured spontaneous intracellular Ca2+ transients at the single cell level in response to physiological extracellular Ca2+. Our results indicate that ER stress increased these spontaneous Ca2+ transients, which were mediated via ER Ca2+ release from the RyR in INS-1 cells. Interestingly, we also found that plasma membrane depolarization was essential for these ER stress–induced spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Depolarization-induced RyR activation occurs in neurons and skeletal muscle (52, 53), however, it is unclear whether the β cell possesses the molecular machinery needed for this process (3). Thus, although the precise mechanisms of β cell ER stress–induced RyR dysfunction require further investigation, we speculate that calcium-induced calcium release (3, 18) or calcium overload–induced calcium release (20) contributes to this phenomenon. Notwithstanding this controversy, our findings offer a potential explanation for how chronic β cell hyperexcitability may exacerbate β-cell failure, especially when layered on a background of ER stress. Notably, early efforts to induce β-cell “rest” with insulin or diazoxide in clinical studies have been associated with diabetes remission and preservation of insulin secretion, whereas sulfonylureas, which chronically depolarize the β cell, have been implicated in hastening β-cell failure in type 2 diabetes (54–56). Again, future studies will be needed to clarify whether therapeutic use of β-cell rest may be effective through reduced RyR2-mediated ER Ca2+ loss and diminished ER stress.

In summary, we have investigated the differential impact of cytokine and ER stress on β cell ER Ca2+ release mechanisms. Our data revealed impaired IP3R function in response to cytokine treatment, whereas RyR-mediated ER Ca2+ leak was preferentially induced under ER stress conditions. RyR inhibition was distinct in its ability to prevent β-cell death and potentiation of the unfolded protein response, suggesting efforts to maintain ER Ca2+ dynamics through stabilization of the RyR may improve β-cell function and survival, and thus represent a potential therapeutic target in diabetes (Fig. 11, G and H).

Experimental procedures

Materials

Tunicamycin and thapsigargin were purchased from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI). Caffeine, d-myo-Inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate hexapotassium salt (IP3), and Xestospongin C were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Fura-2-acetoxymethylester (Fura-2 AM), Mag-Fluo-4 AM, and recombinant mouse IL-1β were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Diazoxide and ATP magnesium salt were from Sigma-Aldrich. Ryanodine and carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) were from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN).

Animals, islets, and cell culture

Male C57BL/6J mice and heterozygous Ins2Akita (Akita) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained under protocols approved by the Indiana University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were kept in a standard light-dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Pancreatic islets were isolated by collagenase digestion, handpicked, and allowed to recover overnight as described previously (57). INS-1 832/13 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 11.1 mm glucose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 mm HEPES, 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 mmol sodium pyruvate, and 50 μmol/ml β-mercaptoethanol (58, 59). Human islets were obtained from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program and cultured as described previously (59). Donor characteristics are shown in Table S1.

β-cell purification using flow cytometry

Mouse islets were gently dissociated using Accutase (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 37 °C for 10 min. Dissociated cells were washed once with 0.1% BSA in PBS and cultured with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Newport Green (25 μm/ml) was then added to the culture media and incubated with dissociated cells for 90 min. Next, Newport Green–stained cells were washed twice with 0.1% PBS and filtered using 5-ml tubes attached to a cell strainer cap. Cells positive and negative for Newport Green (excitation: 485 and emission: 530 nm) were sorted using a BD FACSAria Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). The purity of sorted cell populations was verified by immunofluorescent staining for insulin and glucagon (Fig. S3).

Targeted mass spectrometry

Relative Ryr2 levels in mouse islets and INS-1 cells were measured using a parallel reaction monitoring (PRM)–based targeted MS methodology. In brief, protein extraction was performed by treating with 8 m urea in 50 mm Tris-HCl, followed by sonication. Samples were further processed and digested with Trypsin Gold (Promega, Madison, WI) before Tandem Mass Tag–based labeling of the digested peptides as well as the RyR2 (891-IELGWQYGPVR-901) synthetic trigger peptide. PRM-based nano-LC-MS/MS analyses were performed on a Q Exactive Plus coupled to an Easy-nLC 1200 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were analyzed using SEQUEST-HT as the database search algorithm within Proteome Discoverer (Version 2.2, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Complete methodology can be found in the supporting information.

Immunoblot and quantitative RT-PCR

Immunoblot experiments were performed as described (60) using either the Cell Signaling Caspase-3 Antibody (no. 9662; Danvers, MA) or the Merck Millipore MAB1501 actin antibody (Billerica, MA). Images were analyzed using LI-COR Biosciences Image Studio (Lincoln, NE) and ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Cultured cells or isolated islets were processed for total RNA using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Plus Kit (Valencia, CA), and quantitative RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green I dye and previously published methods (58). The primer sequences employed are detailed in Table S2.

Calcium imaging and IP3R and RyR functional assays

Intracellular Ca2+ was measured using the FLIPR Calcium 6 Assay Kit and a Molecular Devices FlexStation 3 system (Sunnyvale, CA). In brief, INS-1 832/13 cells were plated in black wall, clear bottom, 96-multiwell plates from Costar (Tewksbury, MA) and cultured for 2 days. Following drug or stress treatment, cells were transferred to Ca2+-free Hanks' balanced salt solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 0.2% BSA and EGTA. Calcium 6 reagent was added directly to cells, and cells were incubated for an additional 2 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. ER Ca2+ was estimated by measuring the increase of cytosolic Ca2+ upon application of 10 μm thapsigargin (TG). Data acquisition on the FlexStation 3 system was performed at 37 °C using a 1.52-s reading interval with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 525 nm. For data analysis, values derived from the TG response (ΔF) were divided by resting intracellular Ca2+ (F0), using the formula ΔF/F0.

The ratiometric Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 AM was employed for select experiments using previously described methods and a Zeiss Z1 microscope (9). To measure islet glucose-induced Ca2+ oscillations (GICOs), extracellular glucose was increased from 5 mm to 15 mm. Spontaneous intracellular Ca2+ transients were measured using the method described by Tang et al. (20). Briefly, INS-1 cells or dispersed islet cells were imaged under Ca2+-free conditions using Fura-2 AM. Extracellular Ca2+ was increased in a stepwise fashion (0.1, 0.5, 1.0 mm) to evoke Ca2+ transients until a physiological extracellular Ca2+ concentration of 2 mm was reached. Data were analyzed using Zeiss Zen Blue software.

IP3R and RyR activation was evaluated in response to IP3 and caffeine, respectively, using modifications to the protocol described by Tovey and Taylor (61). INS-1 cells were loaded with the low-affinity Ca2+ indicator, Mag-Fluo-4 AM followed by permeabilization of the plasma membrane with 10 μg/ml saponin, leaving Mag-Fluo-4 AM in the lumen of cellular organelles. Data acquisition on the FlexStation 3 system was performed at 37 °C using a 1.52-s reading interval, with an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an emission wavelength at 525 nm. To establish steady-state ER Ca2+ levels, 1.5 mm Mg-ATP was added; then IP3 or caffeine was applied at the indicated concentrations to activate IP3R and RyR, respectively.

INS-1 cells were transduced with the ER-targeted Ca2+ biosensor D4ER adenovirus (kind gift from Dr. Patrick Gilon) for 10 h, allowed to recover overnight, and treated with 300 nm TM with or without 100 μm Ry for 24 h. To directly image ER Ca2+ levels, INS-1 cells were transfected with an adenovirus encoding the ER-targeted D4ER probe under control of the rat insulin promoter (60), and FLIM was used to monitor ER Ca2+ levels as described previously (60).

Islets isolated from 8- to 10-week-old C57BL/6J mice were transduced with an adenovirus expressing the ER-targeted D4ER probe overnight, allowed to recover, and treated with 300 nm TM with or without 100 μm Ry for 24 h. Islets were transferred to a chamber slide containing Hanks' balanced salt solution, supplemented with 0.2% BSA, 1.2 mm Mg2+, and 2.5 mm Ca2+. Z-stack images were taken using a Zeiss LSM 800 affixed with an Ibidi stage top incubator and intensities of CFP and YFP from positively transduced β cells were quantitated with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) and presented as a ratio. Representative images are shown as maximum intensity projections and were generated using CellProfiler 3.0 (Broad Institute) (62).

Cell death assays and insulin secretion

To measure caspase 3/7 activity, INS-1 cells were cultured in black wall, clear bottom, 96-multiwell plates for 2 days. Following drug or stress treatment, Caspase-Glo reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) was added directly to cells, and cells were incubated for an additional 30 min at room temperature. The luminescence of each sample was measured by using a SpectraMax M5 or iD5 Multi-Mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Cell viability in mouse islets was quantitated using the Live/Dead Cell Viability Assay from Thermo Fisher, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope, and the area of dead cells was calculated as the ratio of ethidium homodimer-1 positive red area (dead) and calcein-AM positive green area (live).

Statistical analysis

Unless indicated, results were displayed as the mean ± S.D. and differences between groups were analyzed for significance using GraphPad Prism Software. When comparing two groups, unpaired Student's t tests were utilized, and differences between two or more groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey-Kramer post hoc test. A p value < 0.05 was used to indicate a significant difference between groups.

Author contributions

W. R. Y., R. N. B., and C. E.-M. conceptualization; W. R. Y., R. N. B., A. L. M., A. B. W., J. D. T., and C. E.-M. data curation; W. R. Y., R. N. B., and C. E.-M. formal analysis; W. R. Y., R. N. B., P. S., F. S., C. A. R., A. B. W., J. D. T., X. T., and T. K. investigation; W. R. Y., R. N. B., F. S., C. A. R., A. L. M., A. B. W., J. D. T., X. T., T. K., and C. E.-M. methodology; W. R. Y., R. N. B., and C. E.-M. writing-original draft; R. N. B. validation; R. N. B. visualization; R. N. B. and C. E.-M. project administration; R. N. B., P. S., C. A. R., A. L. M., A. B. W., J. D. T., X. T., T. K., and C. E.-M. writing-review and editing; A. L. M., T. K., and C. E.-M. supervision; C. E.-M. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Islet and Physiology and Imaging Cores of the Indiana Diabetes Research Center (P30DK097512) and the Indiana University Proteomics Core.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK093954 and UC4 DK 104166 (to C. E-M.); Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Award I01BX001733 (to C. E-M.); and Sigma Beta Sorority, Ball Brothers Foundation, and George and Frances Ball Foundation gifts (to C. E-M.). This work was also supported by NIAID, National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 AI060519 and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship 3-PDF-2017–385-A-N (to R. N. B.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S4 and Tables S1 and S2.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- SERCA

- sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase

- RyR

- ryanodine receptor

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- IP3R

- IP3 receptor

- GICO

- glucose-induced Ca2+ oscillation

- TM

- tunicamycin

- ILHG

- interleukin 1β combined with high glucose

- Ry

- ryanodine

- XeC

- xestospongin C

- FLIM

- fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy

- T-MS

- targeted MS

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- Ctr

- control

- AUC

- area under the curve

- Fura-2 AM

- Fura-2-acetoxymethylester

- CPVT

- catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- TG

- thapsigargin

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- RT-qPCR

- real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

References

- 1. Montero M., Brini M., Marsault R., Alvarez J., Sitia R., Pozzan T., and Rizzuto R. (1995) Monitoring dynamic changes in free Ca2+ concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum of intact cells. EMBO J. 14, 5467–5475 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00233.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michalak M., Robert Parker J. M., and Opas M. (2002) Ca2+ signaling and calcium binding chaperones of the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Calcium 32, 269–278 10.1016/S0143416002001884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilon P., Chae H. Y., Rutter G. A., and Ravier M. A. (2014) Calcium signaling in pancreatic β-cells in health and in type 2 diabetes. Cell Calcium 56, 340–361 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Santulli G., Nakashima R., Yuan Q., and Marks A. R. (2017) Intracellular calcium release channels: An update. J. Physiol. 595, 3041–3051 10.1113/JP272781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ravier M. A., Daro D., Roma L. P., Jonas J. C., Cheng-Xue R., Schuit F. C., and Gilon P. (2011) Mechanisms of control of the free Ca2+ concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum of mouse pancreatic β-cells: Interplay with cell metabolism and [Ca2+]c and role of SERCA2b and SERCA3. Diabetes 60, 2533–2545 10.2337/db10-1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tong X., Kono T., Anderson-Baucum E. K., Yamamoto W., Gilon P., Lebeche D., Day R. N., Shull G. E., and Evans-Molina C. (2016) SERCA2 deficiency impairs pancreatic β-cell function in response to diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 65, 3039–3052 10.2337/db16-0084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guest P. C., Bailyes E. M., and Hutton J. C. (1997) Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ is important for the proteolytic processing and intracellular transport of proinsulin in the pancreatic β-cell. Biochem. J. 323, 445–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tersey S. A., Nishiki Y., Templin A. T., Cabrera S. M., Stull N. D., Colvin S. C., Evans-Molina C., Rickus J. L., Maier B., and Mirmira R. G. (2012) Islet β-cell endoplasmic reticulum stress precedes the onset of type 1 diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse model. Diabetes 61, 818–827 10.2337/db11-1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tong X., Kono T., and Evans-Molina C. (2015) Nitric oxide stress and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase impair β-cell sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2b activity and protein stability. Cell Death Disease 6, e1790 10.1038/cddis.2015.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kono T., Ahn G., Moss D. R., Gann L., Zarain-Herzberg A., Nishiki Y., Fueger P. T., Ogihara T., and Evans-Molina C. (2012) PPAR-γ activation restores pancreatic islet SERCA2 levels and prevents β-cell dysfunction under conditions of hyperglycemic and cytokine stress. Mol. Endocrinol. 26, 257–271 10.1210/me.2011-1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cardozo A. K., Ortis F., Storling J., Feng Y. M., Rasschaert J., Tonnesen M., Van Eylen F., Mandrup-Poulsen T., Herchuelz A., and Eizirik D. L. (2005) Cytokines down-regulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes 54, 452–461 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu S., Kanekura K., Hara T., Mahadevan J., Spears L. D., Oslowski C. M., Martinez R., Yamazaki-Inoue M., Toyoda M., Neilson A., Blanner P., Brown C. M., Semenkovich C. F., Marshall B. A., Hershey T., Umezawa A., Greer P. A., and Urano F. (2014) A calcium-dependent protease as a potential therapeutic target for Wolfram syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E5292–E5301 10.1073/pnas.1421055111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luciani D. S., Gwiazda K. S., Yang T. L., Kalynyak T. B., Bychkivska Y., Frey M. H., Jeffrey K. D., Sampaio A. V., Underhill T. M., and Johnson J. D. (2009) Roles of IP3R and RyR Ca2+ channels in endoplasmic reticulum stress and β-cell death. Diabetes 58, 422–432 10.2337/db07-1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dixit S. S., Wang T., Manzano E. J., Yoo S., Lee J., Chiang D. Y., Ryan N., Respress J. L., Yechoor V. K., and Wehrens X. H. (2013) Effects of CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of ryanodine receptor type 2 on islet calcium handling, insulin secretion, and glucose tolerance. PLoS One 8, e58655 10.1371/journal.pone.0058655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marhfour I., Lopez X. M., Lefkaditis D., Salmon I., Allagnat F., Richardson S. J., Morgan N. G., and Eizirik D. L. (2012) Expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress markers in the islets of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 55, 2417–2420 10.1007/s00125-012-2604-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ramadan J. W., Steiner S. R., O'Neill C. M., and Nunemaker C. S. (2011) The central role of calcium in the effects of cytokines on β-cell function: Implications for type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Cell Calcium 50, 481–490 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fulda S., Gorman A. M., Hori O., and Samali A. (2010) Cellular stress responses: Cell survival and cell death. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 214074 10.1155/2010/214074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beauvois M. C., Arredouani A., Jonas J. C., Rolland J. F., Schuit F., Henquin J. C., and Gilon P. (2004) Atypical Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from a sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 3-dependent Ca2+ pool in mouse pancreatic β-cells. J. Physiol. 559, 141–156 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.067454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Santulli G., Pagano G., Sardu C., Xie W., Reiken S., D'Ascia S. L., Cannone M., Marziliano N., Trimarco B., Guise T. A., Lacampagne A., and Marks A. R. (2015) Calcium release channel RyR2 regulates insulin release and glucose homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 4316 10.1172/JCI84937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tang Y., Tian X., Wang R., Fill M., and Chen S. R. (2012) Abnormal termination of Ca2+ release is a common defect of RyR2 mutations associated with cardiomyopathies. Circ. Res. 110, 968–977 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hotamisligil G. S. (2010) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 140, 900–917 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marciniak S. J., and Ron D. (2006) Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in disease. Physiol. Rev. 86, 1133–1149 10.1152/physrev.00015.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Papa F. R. (2012) Endoplasmic reticulum stress, pancreatic β-cell degeneration, and diabetes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a007666 10.1101/cshperspect.a007666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mekahli D., Bultynck G., Parys J. B., De Smedt H., and Missiaen L. (2011) Endoplasmic-reticulum calcium depletion and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a004317 10.1101/cshperspect.a004317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu M., Hodish I., Rhodes C. J., and Arvan P. (2007) Proinsulin maturation, misfolding, and proteotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15841–15846 10.1073/pnas.0702697104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holz G. G., Leech C. A., Heller R. S., Castonguay M., and Habener J. F. (1999) cAMP-dependent mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ stores by activation of ryanodine receptors in pancreatic β-cells. A Ca2+ signaling system stimulated by the insulinotropic hormone glucagon-like peptide-1-(7–37). J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14147–14156 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans-Molina C., Hatanaka M., and Mirmira R. G. (2013) Lost in translation: Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the decline of β-cell health in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 15, Suppl. 3, 159–169 10.1111/dom.12163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen M. C., Proost P., Gysemans C., Mathieu C., and Eizirik D. L. (2001) Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is expressed in pancreatic islets from prediabetic NOD mice and in interleukin-1 β-exposed human and rat islet cells. Diabetologia 44, 325–332 10.1007/s001250051622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spranger J., Kroke A., Möhlig M., Hoffmann K., Bergmann M. M., Ristow M., Boeing H., and Pfeiffer A. F. (2003) Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes: Results of the prospective population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Diabetes 52, 812–817 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dinarello C. A., Donath M. Y., and Mandrup-Poulsen T. (2010) Role of IL-1β in type 2 diabetes. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 17, 314–321 10.1097/MED.0b013e32833bf6dc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Larsen C. M., Faulenbach M., Vaag A., Vølund A., Ehses J. A., Seifert B., Mandrup-Poulsen T., and Donath M. Y. (2007) Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 1517–1526 10.1056/NEJMoa065213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li N., Wang Q., Sibrian-Vazquez M., Klipp R. C., Reynolds J. O., Word T. A., Scott L. Jr., Salama G., Strongin R. M., Abramson J. J., and Wehrens X. H. (2017) Treatment of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice using novel RyR2-modifying drugs. Int. J. Cardiol. 227, 668–673 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marks A. R. (2013) Calcium cycling proteins and heart failure: Mechanisms and therapeutics. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 46–52 10.1172/JCI62834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kang G., Chepurny O. G., and Holz G. G. (2001) cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor II (Epac2) mediates Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in INS-1 pancreatic β-cells. J. Physiol. 536, 375–385 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0375c.xd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tarasov A. I., Griffiths E. J., and Rutter G. A. (2012) Regulation of ATP production by mitochondrial Ca2+. Cell Calcium 52, 28–35 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mitchell K. J., Pinton P., Varadi A., Tacchetti C., Ainscow E. K., Pozzan T., Rizzuto R., and Rutter G. A. (2001) Dense core secretory vesicles revealed as a dynamic Ca2+ store in neuroendocrine cells with a vesicle-associated membrane protein aequorin chimaera. J. Cell Biol. 155, 41–51 10.1083/jcb.200103145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnson J. D., Kuang S., Misler S., and Polonsky K. S. (2004) Ryanodine receptors in human pancreatic β cells: Localization and effects on insulin secretion. FASEB J. 18, 878–880 10.1096/fj.03-1280fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao F., Li P., Chen S. R., Louis C. F., and Fruen B. R. (2001) Dantrolene inhibition of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels. Molecular mechanism and isoform selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13810–13816 10.1074/jbc.M006104200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takasawa S., Akiyama T., Nata K., Kuroki M., Tohgo A., Noguchi N., Kobayashi S., Kato I., Katada T., and Okamoto H. (1998) Cyclic ADP-ribose and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate as alternate second messengers for intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in normal and diabetic beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2497–2500 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng C. W., Villani V., Buono R., Wei M., Kumar S., Yilmaz O. H., Cohen P., Sneddon J. B., Perin L., and Longo V. D. (2017) Fasting-mimicking diet promotes Ngn3-driven β-cell regeneration to reverse diabetes. Cell 168, 775–788.e712 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waning D. L., Mohammad K. S., Reiken S., Xie W., Andersson D. C., John S., Chiechi A., Wright L. E., Umanskaya A., Niewolna M., Trivedi T., Charkhzarrin S., Khatiwada P., Wronska A., Haynes A., et al. (2015) Excess TGF-β mediates muscle weakness associated with bone metastases in mice. Nat. Med. 21, 1262–1271 10.1038/nm.3961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Del Prete D., Checler F., and Chami M. (2014) Ryanodine receptors: Physiological function and deregulation in Alzheimer disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 9, 21 10.1186/1750-1326-9-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Landstrom A. P., Dobrev D., and Wehrens X. H. T. (2017) Calcium signaling and cardiac arrhythmias. Circ. Res. 120, 1969–1993 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Priori S. G., Napolitano C., Tiso N., Memmi M., Vignati G., Bloise R., Sorrentino V., and Danieli G. A. (2001) Mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene (hRyR2) underlie catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 103, 196–200 10.1161/01.CIR.103.2.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wehrens X. H., Lehnart S. E., Huang F., Vest J. A., Reiken S. R., Mohler P. J., Sun J., Guatimosim S., Song L. S., Rosemblit N., D'Armiento J. M., Napolitano C., Memmi M., Priori S. G., Lederer W. J., and Marks A. R. (2003) FKBP12.6 deficiency and defective calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) function linked to exercise-induced sudden cardiac death. Cell 113, 829–840 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00434-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kyrychenko S., Poláková E., Kang C., Pocsai K., Ullrich N. D., Niggli E., and Shirokova N. (2013) Hierarchical accumulation of RyR post-translational modifications drives disease progression in dystrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 97, 666–675 10.1093/cvr/cvs425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marmugi A., Parnis J., Chen X., Carmichael L., Hardy J., Mannan N., Marchetti P., Piemonti L., Bosco D., Johnson P., Shapiro J. A., Cruciani-Guglielmacci C., Magnan C., Ibberson M., Thorens B., Valdivia H. H., Rutter G. A., and Leclerc I. (2016) Sorcin links pancreatic β-cell lipotoxicity to ER Ca2+ stores. Diabetes 65, 1009–1021 10.2337/db15-1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gardner B. M., and Walter P. (2011) Unfolded proteins are Ire1-activating ligands that directly induce the unfolded protein response. Science 333, 1891–1894 10.1126/science.1209126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ferreiro E., Resende R., Costa R., Oliveira C. R., and Pereira C. M. (2006) An endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptotic pathway is involved in prion and amyloid-β peptides neurotoxicity. Neurobiol. Dis. 23, 669–678 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu R. F., Ma Z., Liu Z., and Terada L. S. (2010) Nox4-derived H2O2 mediates endoplasmic reticulum signaling through local Ras activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 3553–3568 10.1128/MCB.01445-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Santos C. X., Tanaka L. Y., Wosniak J., and Laurindo F. R. (2009) Mechanisms and implications of reactive oxygen species generation during the unfolded protein response: Roles of endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductases, mitochondrial electron transport, and NADPH oxidase. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 2409–2427 10.1089/ars.2009.2625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Plotkin J. L., Shen W., Rafalovich I., Sebel L. E., Day M., Chan C. S., and Surmeier D. J. (2013) Regulation of dendritic calcium release in striatal spiny projection neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 110, 2325–2336 10.1152/jn.00422.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Protasi F. (2002) Structural interaction between RYRs and DHPRs in calcium release units of cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. Front. Biosci. 7, d650–658 10.2741/A801,10.2741/protasi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim J. Y., Lim D. M., Park H. S., Moon C. I., Choi K. J., Lee S. K., Baik H. W., Park K. Y., and Kim B. J. (2012) Exendin-4 protects against sulfonylurea-induced β-cell apoptosis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 118, 65–74 10.1254/jphs.11072FP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Turner R. C., Cull C. A., Frighi V., and Holman R. R. (1999) Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: progressive requirement for multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA 281, 2005–2012 10.1001/jama.281.21.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van Raalte D. H., and Verchere C. B. (2017) Improving glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: Stimulate insulin secretion or provide β-cell rest? Diabetes Obes. Metab. 19, 1205–1213 10.1111/dom.12935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stull N. D., Breite A., McCarthy R., Tersey S. A., and Mirmira R. G. (2012) Mouse islet of Langerhans isolation using a combination of purified collagenase and neutral protease. J. Vis. Exp. 10.3791/4137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Evans-Molina C., Robbins R. D., Kono T., Tersey S. A., Vestermark G. L., Nunemaker C. S., Garmey J. C., Deering T. G., Keller S. R., Maier B., and Mirmira R. G. (2009) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activation restores islet function in diabetic mice through reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress and maintenance of euchromatin structure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 2053–2067 10.1128/MCB.01179-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ogihara T., Chuang J. C., Vestermark G. L., Garmey J. C., Ketchum R. J., Huang X., Brayman K. L., Thorner M. O., Repa J. J., Mirmira R. G., and Evans-Molina C. (2010) Liver X receptor agonists augment human islet function through activation of anaplerotic pathways and glycerolipid/free fatty acid cycling. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5392–5404 10.1074/jbc.M109.064659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Johnson J. S., Kono T., Tong X., Yamamoto W. R., Zarain-Herzberg A., Merrins M. J., Satin L. S., Gilon P., and Evans-Molina C. (2014) Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox protein 1 (Pdx-1) maintains endoplasmic reticulum calcium levels through transcriptional regulation of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2b (SERCA2b) in the islet βcell. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 32798–32810 10.1074/jbc.M114.575191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tovey S. C., and Taylor C. W. (2013) High-throughput functional assays of IP3-evoked Ca2+ release. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2013, 930–937 10.1101/pdb.prot073072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lamprecht M. R., Sabatini D. M., and Carpenter A. E. (2007) CellProfiler: Free, versatile software for automated biological image analysis. BioTechniques 42, 71–75 10.2144/000112257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.