Abstract

The dNTP triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 is a regulator of cellular dNTP pools. Given its central role in nucleotide metabolism, SAMHD1 performs important functions in cellular homeostasis, cell cycle regulation, and innate immunity. It therefore represents a high-profile target for small molecule drug design. SAMHD1 has a complex mechanism of catalytic activation that makes the design of an activating compound challenging. However, an inhibitor of SAMHD1 could serve multiple therapeutic roles, including the potentiation of antiviral and anticancer drug regimens. The lack of high-throughput screens that directly measure SAMHD1 catalytic activity has impeded efforts to identify inhibitors of SAMHD1. Here we describe a novel high-throughput screen that directly measures SAMHD1 catalytic activity. This assay results in a colorimetric end point that can be read spectrophotometrically and utilizes bis(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate as the substrate and Mn2+ as the activating cation that facilitates catalysis. When used to screen a library of Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs, this HTS identified multiple novel compounds that inhibited SAMHD1 dNTPase activity at micromolar concentrations.

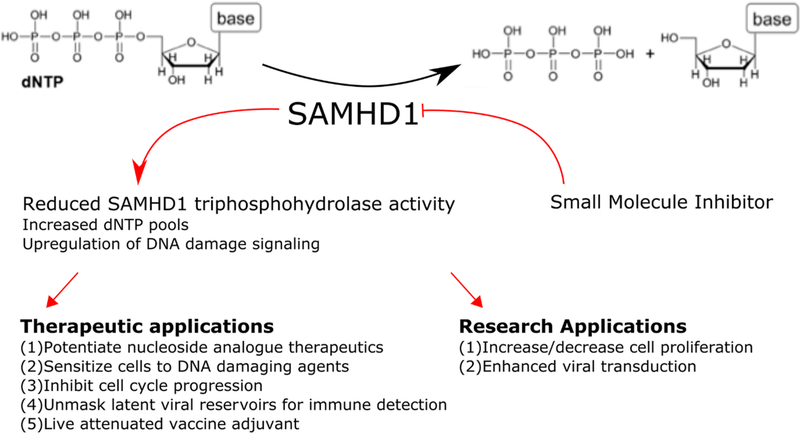

Graphical Abstract

Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) are the building blocks of DNA. As such, the pathways controlling their synthesis and degradation are strictly regulated.1–3 The enzyme SAMHD1 (sterile α motif and histidine- and aspartic acid-containing protein 1) performs a critical function within nucleotide metabolism pathways.4 It is a deoxynucleoside triphosphohydrolase that belongs to a class of HD enzymes characterized by their ability to catalyze divalent cation-dependent hydrolysis of phosphomonoester-containing substrates, including phosphorylated nucleosides.5 SAMHD1 specifically catalyzes the hydrolysis of the triphosphate group of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) at the α-phosphate, resulting in the cognate nucleoside and inorganic polyphosphate as reaction products.6,7 Through its catabolic capacity to degrade dNTPs, SAMHD1 depletes cellular dNTP pools below potentially mutagenic concentrations.8–10 The ability to deplete dNTP pools also distinguishes SAMHD1 as an important effector of the innate immune response. In noncycling myeloid and lymphoid cells, where it is expressed at high levels, SAMHD1 acts as a restriction factor against HIV-1 and other viral infections11–15 by depleting dNTP levels below a threshold required by viral DNA polymerases.16 More recently, SAMHD1 has been connected to additional cellular processes, including regulation of cell cycle progression17,18 and DNA repair.19,20

The catalytic activity of SAMDH1 is regulated through a complex mechanism of sequential nucleotide triphosphate binding in two regulatory sites on each SAMHD1 monomer. Binding of a guanosine nucleotide triphosphate at regulatory site 1 (RS1) and any of the four canonical dNTPs at regulatory site 2 (RS2) induces a conformational shift that enables SAMHD1 to form the catalytically active tetramer.21–23 In this way, SAMHD1 catalytic activity is effectively upregulated by increases in the level of its endogenous substrate, allowing for an elegant mechanism of cellular control when dNTP levels are elevated above the homeostatic range. SAMHD1 activity is further regulated through its expression profile where it is constitutively expressed in different cell types, with especially high levels observed in noncycling cells of hematopoietic lineage.24 SAMHD1 is also post-translationally modified by oxidation and phosphorylation, which alter the enzyme’s catalytic activity, oligomerization, and viral restriction capacity, while ensuring appropriate levels of dNTPs for DNA replication and repair at corresponding cell cycle stages.4,25,26

As the importance of SAMHD1 in normal cellular functioning becomes more apparent, so too does the interest in targeting SAMHD1 therapeutically. Targeting nucleotide metabolism is a common therapeutic strategy for anticancer and antiviral therapeutic regimens.27–29 SAMHD1 activity has been demonstrated to reduce the efficacy of HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors in cells and their ability to prevent productive HIV infection.30–33 While upregulation of the activity of SAMHD1 may represent a gold standard for SAMHD1 drug discovery in relation to viral infection, the complex mechanism of activation makes this a challenging task. However, the rationale for the more straightforward design of a robust SAMHD1 inhibitor may be just as strong (Figure 1). Recently, it has been reported that several classes of nucleotide analogue antimetabolite therapeutics (NAATs) are substrates for SAMHD1.34 Specifically, the phosphorylated species of arabinose-derived NAATs, which lack the axial 2′-hydroxyl group on the sugar moiety and are commonly used in anticancer treatment regimens, have been identified as targets for degradation by SAMHD1 in vitro and in vivo.35,36 In patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the efficacy of the standard of care therapeutic agent Ara-C was inversely related to levels of SAMHD1 expression.37 A small molecule inhibitor of SAMHD1 delivered as a complementary therapy may enhance the therapeutic window by potentiating the efficacy of NAATs and result in improved patient outcomes.38,39 Inhibition of SAMHD1 may also prove to be an effective complementary anticancer therapy in conjunction with DNA-damaging agents or compounds that target the DNA damage response. Larger or asymmetric dNTP pools are demonstrated to enhance DNA damage and upregulate the DNA damage response.40,41 Additionally, studies have shown that knockdown of SAMHD1 results in larger dNTP pools and cell cycle arrest.17 It thus may be possible to synergistically induce genomic instability by modulating SAMHD1 catalytic capacity to diminish cellular viability and proliferative capacity.42

Figure 1.

Schematic depicting the potential therapeutic and research applications of a small molecule inhibitor of SAMHD1.

In addition to potential anticancer indications, a SAMHD1 inhibitor may also have potential applications in antiretroviral therapy. Retroviruses like HIV can infect immune sentinel cells, albeit inefficiently, even in the presence of antiretroviral therapy. Several studies suggest that by reducing the efficiency of replication in infected dendritic cells and macrophages, enzymes like SAMHD1 and TREX1 suppress a full immune response to chronic and latent viral infection.43–47 Inhibition of SAMHD1 may enhance productive viral infection and thereby initiate a robust immune response that unmasks the subclinical infection. This approach might also be useful as an adjuvant for live attenuated vaccines.

Despite the strong clinical and research rationale for the design of a SAMHD1 inhibitor, limited progress has been made toward the development of a small molecule that potently inhibits its catalytic activity. This may be in part due to the lack of direct and scalable high-throughput screens (HTS). While several HTS assays have been reported, they rely on enzyme-coupled protocols to detect the inorganic phosphate that accumulates as a product of dNTP hydrolysis.48,49 In this study, we identify and validate a direct HTS assay for detecting inhibitors of SAMHD1 catalytic activity. The assay described in this study is a direct colorimetric measure of SAMHD1 catalytic activity based on the ability of SAMHD1 to hydrolyze the phosphodiester model compound bis(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate (b4NPP) in the presence of Mn2+. It represents a direct, cost-effective, and scalable approach for the rapid screening of large libraries of compounds as inhibitors of SAMHD1 triphosphohydrolase activity. Using this technique, we identify several compounds from a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug library that inhibit SAMHD1. These novel inhibitors represent unique molecular scaffolds with the potential for further chemical optimization toward the design of a robust small molecule inhibition of SAMHD1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were purchased from Sigma. dGTP was purchased from Promega (100 mM solution). 2′-Deoxyadenosine 5′-O-(1-thiotriphosphate) (dATPαS) and 2′-deoxyadenosine 5′-O-(1-thiotriphosphate) (dGTPαS) were from TriLink Biotechnologies. The HTS library (Screen-Well FDA Approved Drug Library version 1.5, Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.) was a generous gift from L. Poole.

SAMHD1 Expression and Purification.

Recombinant SAMHD1 wild type (WT) and H206A were overexpressed and purified as described previously.25 Briefly, the full-length human SAMHD1 gene was cloned into a modified pET28 expression vector (pLM303-SAMHD1) that contained an N-terminal MBP tag and an intervening rhinovirus 3C protease cleavage site. Expression constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21* and grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37 °C with shaking to an OD600 of 0.6. Cultures were induced with 0.3 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), rapidly cooled on ice to 20 °C, and then allowed to express for 16–18 h at 16 °C. Harvested cells were resuspended in amylose column buffer (ACB) [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol] and lysed using an Avestin Emulsiflex-C5 cell homogenizer. Cell debris was cleared by centrifugation at 18.5K rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, and the cleared lysate was passed over amylose high-flow resin (New England Biolabs) and washed with 3 column volumes of ACB and 1 M NaCl to remove residual nucleic acid. Bound MBP-SAMHD1 was eluted over a linear gradient with ACB and 20 mM maltose. The desired fractions were pooled and dialyzed overnight against heparin column buffer (HCB) [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol]. PreScission Protease (GE Biosciences) was added (100:1) to the MBP-SAMHD1 dialysate to cleave the MBP tag. The SAMHD1-containing sample was separated from the cleaved MBP using a 5 mL Heparin HiTrap column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and eluted using a linear gradient of HCB and 2 M NaCl. SAMHD1-containing fractions were again pooled and further purified using a Superdex 200 size exclusion chromatography column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol. The protein was concentrated and flash-frozen in individual aliquots using liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until it was used.

SAMHD1 Deoxynucleoside Triphosphohydrolase (dNTPase) Activity Assay.

Individual protein aliquots were thawed and mixed with reaction buffer [final concentrations of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM activating cation (MgCl2, MnCl2, or CoCl2), 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM TCEP]. Aliquots were then transferred to a clear flat-bottom 96-well polystyrene microassay plate. Reactions were initiated by adding either 500 μM dATP, 500 μM dATP and 50 μM GTP, or 500 μM dGTP alone to a final reaction volume of 100 μL. Formation of the deoxynucleoside was used to measure the progress of the reaction. The SAMHD1 concentration in all reactions was 500 nM. Reactions were quenched using EDTA to a final concentration of 20 mM after 10 or 20 min, depending on the experiment. In experiments that aimed to investigate the inhibitory effects of top hits from the HTS, MgCl2 was used as the activating cation, and 2 μL of each compound [2 mg/mL in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] was added to the enzyme mixture 10 min prior to the addition of dGTP.

dNTPase reaction products were analyzed using ion pair reverse phase chromatography on a Waters HPLC system. A CAPCell PAK C18 column (Shiseido Fine Chemicals) was equilibrated with 20 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM tetra-n-butylammonium phosphate, and 5% methanol. Reactants and products were eluted with a linear gradient of methanol from 5 to 60%. A260 was used to measure elutant peaks, and quantification was performed using Empower Software to integrate the area under each reaction component peak.

SAMHD1 Bis(4-nitrophenyl) Phosphate (b4NPP) Assay.

Frozen aliquots of SAMHD1 were thawed and diluted into HTS reaction buffer (HTS-RB) [final concentrations of 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MnCl2, 2% glycerol, 0.5% DMSO, and 0.5 mM TCEP] and transferred to a clear flat-bottom 96-well polystyrene microassay plate. If present in the reaction mixture, activating nucleotides were added at the indicated concentrations; 64 mM bis(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate stocks were made from powder in ultrapure water and stored at −20 °C until they were used. The reaction was initiated by adding b4NPP that had been further diluted in water to a final concentration of 2 mM and a final volume of 100 μL. The hydrolysis of b4NPP to p-nitrophenol and pnitrophenyl phosphate was assessed over a period of 45 min by measuring the increase in absorbance at 410 nm on a Tecan Infinite M1000Pro plate reader. Reactions with no enzyme were used as baseline controls. Reaction slopes were calculated from the first 20 min of the reaction to ensure the accurate determination of initial reaction velocities.

Dynamic Light Scattering.

SAMHD1 particle size distributions as a function of hydrodynamic diameter (DH) were determined as described previously25 with several minor changes. Briefly, SAMHD1 was transferred to DLS buffer [50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MnCl2] using a microspin column packed with BioGel-P6 resin (Bio-Rad). The 200 μL samples were prepared by incubating SAMHD1 with the indicated concentrations of b4NPP (2 mM) and activating nucleotides (25 μM GTP and 100 μM dATPαS). The final concentration of SAMHD1 in the samples was 0.2 mg/mL. SAMHD1 solutions were analyzed using a Malvern Nano-S Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, U.K.). Raw intensity-weighted data were converted to the volume percent distribution to mitigate the impact of small amounts of aggregated protein.

High-Throughput Screen.

High-throughput screens were conducted like the b4NPP assay and designed following the principles outlined in Early Drug Discovery and Development Guidelines: For Academic Researchers, Collaborators, and Start-up Companies.50 SAMHD1 was diluted in HTS-RB to a final reaction concentration of 500 nM and transferred to a clear flat-bottom 96-well polystyrene microassay plate; 2 μL of each compound (2 mg/mL in DMSO) from Screen-Well FDA Approved Drug Library Version 1.5 was added to the SAMHD1 solution and allowed to sit at 21 °C for 10 min. The reaction was initiated by the addition of b4NPP to a final concentration of 2 mM in a final reaction volume of 100 μL. All reaction mixtures were prepared using a Gryphon high-throughput liquid handling platform (Art Robbins Instruments).

The ability of SAMHD1 to hydrolyze b4NPP to p-nitrophenol and p-nitrophenyl phosphate in the presence of the inhibitor was assessed over a period of 45 min by measuring the increase in the absorbance at 410 nm on a Tecan Infinite M1000Pro plate reader. A matched reaction for each compound in which no SAMHD1 was added served as a baseline control for nonspecific compound–substrate interactions and was subtracted from the absorbance reading for the enzyme-containing reaction mixture. In each plate, wells containing SAMHD1, b4NPP, and neat DMSO served as positive controls to which experimental wells were normalized. Additional negative controls were composed of reaction mixtures containing HTS-RB, b4NPP, and DMSO only. Reaction velocities were calculated from the slope of the absorbance increase over the first 20 min of the reaction, which was within the linear range of the assay. The percent activity was calculated from the reaction slopes using eq 1.

| (1) |

The Z′ factor, a measure of assay quality and reproducibility, was calculated using eq 2, in which positive (p) and negative (n) control values, representing reactions with and without enzyme, respectively, are tabulated to produce a number between 0 and 1. A value above 0.5 represents a quality assay.51

| (2) |

Dose–Response Curves and Determination of IC50 Values.

Dose–response reaction mixtures were prepared in a manner similar that for dNTPase reactions described above, with several notable changes. SAMHD1 was diluted into reaction buffer [final concentrations of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM TCEP, 1 mM DTT, 0.005 mg mL−1 BSA, 2% glycerol, and 0.025% Tween 20] before being transferred to a clear flat-bottom 96-well polystyrene microassay plate. In experiments in which dCTP served as the substrate, the reaction buffer contained 10 μM GTP and 25 μM dATPαS to preform the activated tetramer. The 10× stocks of inhibitory compounds were prepared by 2:1 serial dilution in 100% DMSO. Compounds were added to the SAMHD1 solution and allowed to incubate for 10 min at 21 °C before the reaction was initiated by the addition of dGTP or dCTP. A final concentration of 150 μM dNTP substrate was selected as a concentration similar to the reported SAMHD1 KM value that results in reproducible and quantifiable peaks when analyzed by HPLC. The final SAMHD1 concentration in the reaction mixture was 250 nM. Reactions were quenched after 10 min by the addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 20 mM to ensure that no more than 20% of dNTP was converted to dN. Reaction contents were analyzed using the HPLC method described above. Data were fit to normalized nonlinear regression with variable Hill slopes in Graphpad Prism 7.00 using eq 3:

| (3) |

In Silico Docking Simulations.

Docking simulations were performed using the Autodock Vina52 plugin for Chimera molecular visualization software. The SAMHD1 crystal structure of Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 4BZC_A was used as the docking receptor, and ligands were docked into the active site (center X 15.75, Y 27.5, Z 42.5; size X 22.5, Y 21.5, Z 18.5).

Data and Statistical Analysis.

Charts and graphs were generated using SigmaPlot version 13.0 (Systat Software, Inc.) or GraphPad Prism version 7.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), which were also used for statistical analysis, t test comparisons, and linear and nonlinear regression. Statistical significance was determined at the p < 0.01 level (one asterisk). Molecular representations were generated using Chimera.53

RESULTS

SAMHD1 Hydrolyzes b4NPP with Manganese and without an Activating Nucleotide.

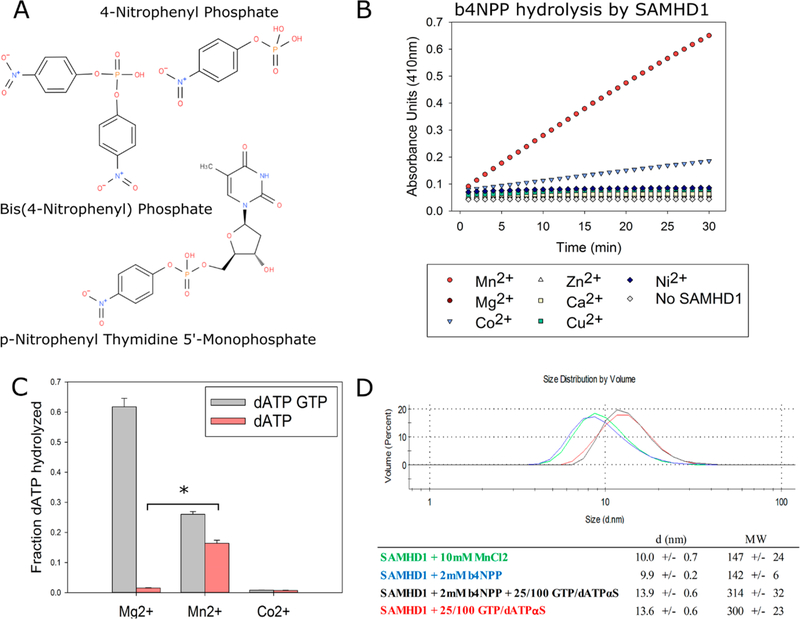

To develop a direct and quantitative assay of SAMDH1 catalytic activity that could be rapidly scaled up for high-throughput screening, several potential reporter compounds were investigated as possible SAMHD1 substrates. The compounds selected for testing [p-nitrophenyl thymidine monophosphate (pNP-TMP), bis(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate (b4NPP), and 4-nitrophenyl phosphate (4NPP)] contained either a phosphodiester or a phosphomonoester bond that structurally resembles those found in dNTPs and are commonly used as surrogate substrates for enzymes with phosphatase, phosphohydrolase, or phosphodiesterase functions similar to those of SAMHD154–58 (Figure 2A). When hydrolyzed, these compounds produce yellow 4-nitrophenol as a reaction product. Its accumulation is stoichiometrically proportional to the amount of parent compound hydrolyzed and can be determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the absorbance at 410 nm.

Figure 2.

Mn2+ activates SAMHD1 catalytic activity against dNTPs and phosphodiester-containing compounds. (A) Chemical structures of compounds tested as substrates of SAMHD1. (B) SAMHD1 hydrolyzes b4NPP in the presence of Mn2+ and to a lesser extent Co2+ at a steady rate over the course of 30 min. (C) SAMHD1 is able to hydrolyze dATP when activated by Mn2+ in the absence of GTP (*p < 0.01). (D) Weight-average distribution of SAMHD1 (molecular weight of 73 kDa) under different conditions as determined by dynamic light scattering. Mn2+ or b4NPP does not induce or inhibit tetramerization.

Initial assay development consisted of determining the catalytic activity of SAMHD1 toward the surrogate compounds under varying conditions (e.g., with and without activating nucleotides, varying enzyme and substrate concentrations, buffers, salts, pH levels, and divalent metal cations). While limited activity was observed under any conditions in which 4NPP and pNP-TMP were used as a substrate, a robust signal was generated when SAMHD1 was incubated with b4NPP in the presence of Mn2+ and to a lesser extent Co2+ (Figure 2B and Figure S1A). This effect held true even in the absence of activating nucleotides. This presented an unexpected result, as the canonical method for activating SAMHD1 is incubation with activating nucleotides to form the catalytically competent tetramer. The metal ion Mg2+ is also predominantly cited in SAMHD1 literature as the cation coordinated by the active site histidine and aspartic acid residues that facilitates substrate binding and triphosphohydrolase activity.

Seeking to further assess the Mn2+-dependent activation of SAMHD1, we conducted a series of dNTPase experiments in which SAMHD1 was activated using Mg2+, Mn2+, or Co2+. dATP was added to the reaction mixture in excess to act as both the substrate and the secondary activating nucleotide in the presence or absence of GTP. As expected, in the sample containing Mg2+, dATP was readily hydrolyzed when GTP was present but not in its absence. This is in accordance with the current model of SAMHD1 catalytic activation in which a d/GTP molecule binds in the RS1 and subsequent binding of any of the four canonical dNTPs at RS2 facilitates the formation of the catalytically competent holoenzyme. However, in samples containing Mn2+, SAMHD1 was able to hydrolyze dATP without GTP present in the reaction mixture, albeit with a decreased efficiency (Figure 2C). Dynamic light scattering, which measures the weight-average particle size distribution as a function of hydrodynamic diameter, was utilized to examine the oligomeric state of SAMHD1 under the experimental conditions where Mn2+ was used as the activating cation. The data reveal that Mn2+ or b4NPP does not promote tetramerization on its own but that SAMHD1 is capable of tetramerization in the presence of both Mn2+ and b4NPP (Figure 2D). When considered together, the DLS data and Mn2+-induced hydrolysis of b4NPP and dATP suggest that Mn2+ is capable of catalytically activating monomeric SAMHD1 and that this characteristic can be exploited in the design of a HTS.

Validating the HTS as a Specific Measure of SAMHD1 Catalytic Activity.

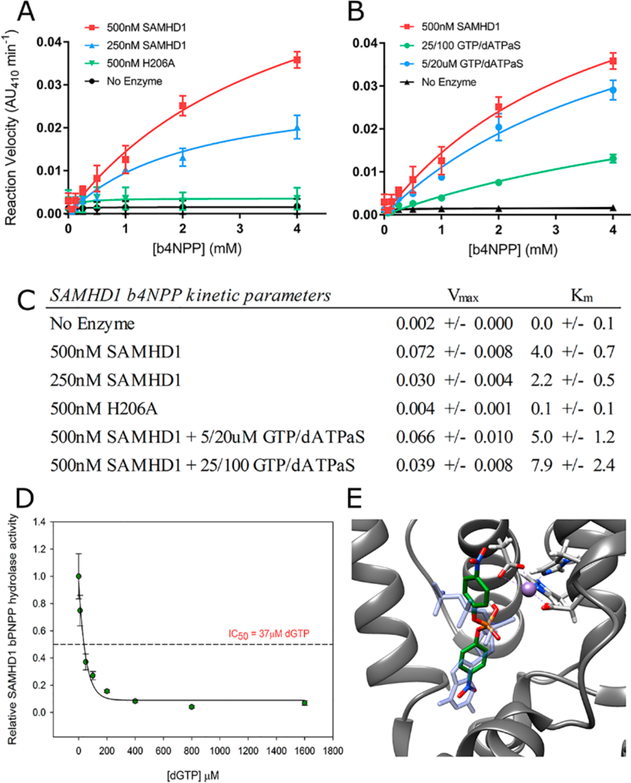

Having identified an initial scalable assay in which SAMHD1 was catalytically active against both its natural substrate and a reporter compound, the next steps consisted of validation and optimization of the specific conditions for screening. Kinetic analyses of b4NPP hydrolysis by SAMHD1 under varying conditions were performed to identify the ideal reaction conditions; 4 mM b4NPP represented the upper limit of these analyses as b4NPP exhibited diminished solubility above this concentration. As expected for a true enzyme–substrate relationship, changes in the enzyme concentration resulted in equivalent changes to the reaction velocity but did not significantly alter the KM (Figure 3A,C). Under conditions where either no SAMHD1 or a catalytically inactive mutant (H206A) was added to the reaction mixture, b4NPP hydrolysis was not observed. These data provide evidence of SAMHD1-mediated b4NPP hydrolysis utilizing active site chemistry and thereby underscore the applicability of this assay as a proxy for endogenous SAMHD1 activity.

Figure 3.

b4NPP–SAMHD1 assay that specifically measures SAMHD1 catalytic activity. (A) Kinetic analysis of the effect of varying the SAMHD1 concentration on b4NPP hydrolysis. H206A is a catalytically inactive mutant. (B) Kinetic analysis of SAMHD1-mediated b4NPP hydrolysis in the presence of varying concentrations of activating nucleotides. (C) Calculated kinetic parameters for both sets of experiments. (D) dGTP is able to inhibit SAMHD1 b4NPP hydrolysis at low micromolar concentrations. SAMHD1 activity was normalized to the condition with no dGTP present. (E) Computational docking simulation of b4NPP (green) in the SAMHD1 active site that aligns it with dGTP (blue) from the crystal structure (PDB entry 4BZC_A).

Under conditions of enzyme tetramerization, the kinetic data indicate that b4NPP binds directly to the active site and competes with the dGTP substrate. Kinetic analyses were conducted in the presence of activating nucleotides in an effort to determine the effect of SAMHD1 tetramerization on b4NPP hydrolysis (Figure 3B,C). GTP and nonhydrolyzable dATPαS were used as activating nucleotides. Together, they are able to induce SAMHD1 tetramerization but are not substrates for the enzyme. At the highest concentration of activating nucleotides tested, in which GTP and dATPαS were present in excess resulting in an almost complete shift in the oligomeric equilibrium to the tetrameric species, SAMHD1 retained the capacity to hydrolyze b4NPP. Increasing concentrations of GTP and dATPαS, however, were inversely correlated to reaction velocity. The precise mechanism of inhibition by activating nucleotides is unclear, although the decreased Vmax at the highest concentration of activating nucleotides suggests that tetramerization, and the subsequent conformational shifts that occur, may decrease the binding affinity of b4NPP at the active site relative to the monomer.

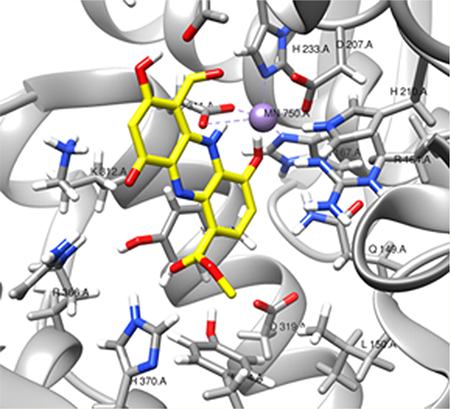

It is also possible that increasing levels of nucleotides are able to outcompete b4NPP for access to the active site. Indeed, increasing concentrations of dGTP completely inhibited SAMHD1-mediated b4NPP hydrolysis in the low micromolar range (Figure 3D). This implies b4NPP can bind in the active site but is outcompeted for access to the active site in the presence of the natural SAMHD1 substrate. Computational docking software was used to further investigate the binding of b4NPP to SAMHD1. Simulations place b4NPP in a similar orientation within the active site as the dGTP molecule found in the holoenzyme crystal structure (PDB entry 4BZC_A) and estimated a KD of 2.1 μM (Figure 3E). In this simulation, the b4NPP phosphate group is properly oriented for chemistry to occur, as it is aligned with the α-phosphate of dGTP, the bond normally hydrolytically cleaved by SAMHD1 catalysis. As a control, a dGTP binding in the active site of SAMHD1 was also simulated (Figure S2). The docking software modeled dGTP in a position almost identical to that found in the crystal structure, with an estimated KD of 0.14 μM. This provides confidence in the model of b4NPP docking in the active site and supports the model of dNTPs outcompeting b4NPP as the active site. In summary, these kinetic and binding analyses strongly support SAMHD1-mediated hydrolysis of b4NPP at its active site in both the monomeric and tetrameric state while suggesting that dNTPs can inhibit b4NPP hydrolysis through a combination of competitive and noncompetitive inhibition.

HTS of FDA-Approved Drugs Identified Multiple Potential Inhibitors of SAMHD1.

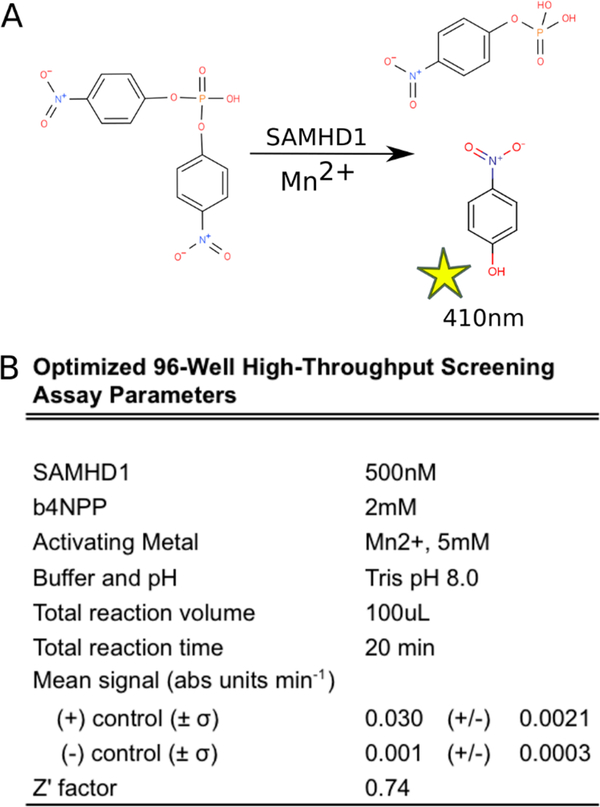

Validation and optimization of the b4NPP–SAMHD1 assay enabled the identification of the optimal conditions for screening a larger library of compounds (Figure 4A,B). This screen was performed using 500 nM SAMHD1 activated with 5 mM MnCl2 and in the absence of any activating nucleotides. b4NPP was used at a final substrate concentration of 2 mM. These conditions generate a robust and easily detectable signal that lies well within the linear range of the assay (Figure S3). In an effort to remain conscious of ultimate scalability, they also represent the minimal necessary components to generate a replicable and accurate measure of the catalytic activity of SAMHD1. The potential to further modify the assay through the addition of activating nucleotides to specifically investigate the tetrameric active site configuration is possible (Figure S3) but would include additional reagent cost and may not provide significant benefit in terms of lead generation.

Figure 4.

b4NPP–SAMHD1 HTS (A) assay schematic and (B) optimized parameters.

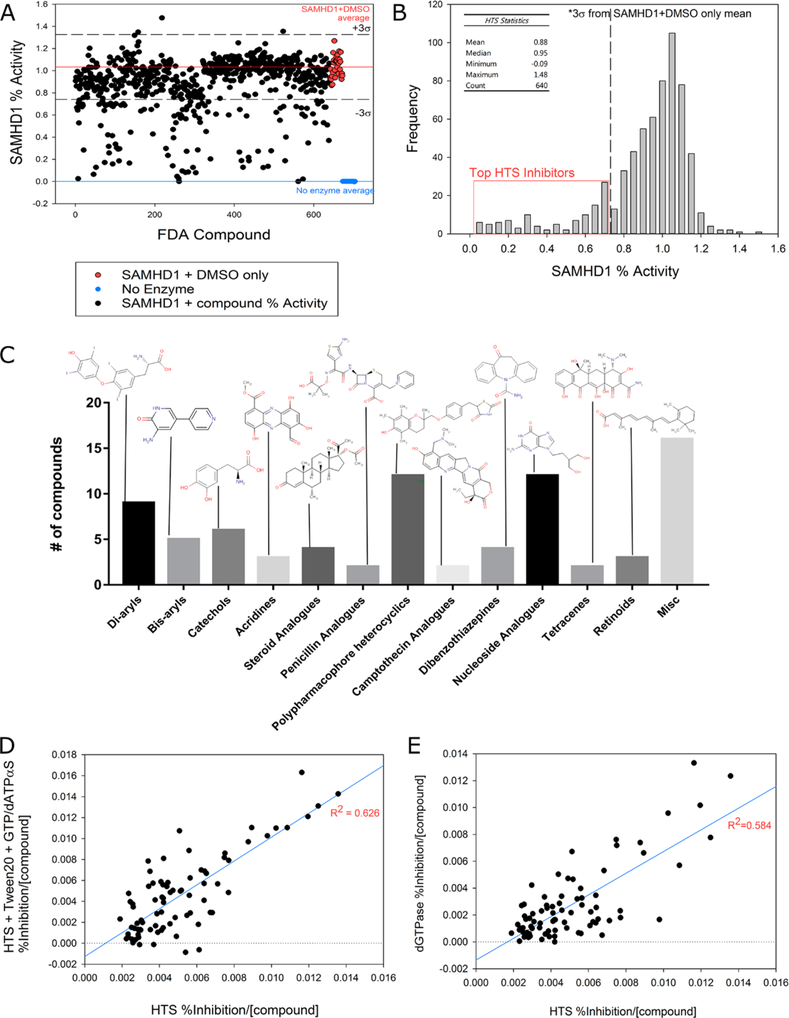

Once established, the optimized conditions were used to assay a library of 640 FDA-approved drugs for the ability to inhibit SAMHD1-mediated b4NPP hydrolysis. While this library encompassed only a small number of compounds relative to larger HTS libraries, all compounds were FDA-approved chemical entities with broad structural diversity and therapeutic indications; 2 μL of each compound (2 mg/mL in DMSO) was added to the enzyme solution 10 min prior to initiating reactions with b4NPP. As expected, a majority of compounds exhibited limited or no effect on SAMHD1 catalytic activity relative to the average of the positive control samples (SAMHD1 and DMSO only) (Figure 5A,B). However, approximately 80 compounds inhibited SAMHD1 catalysis of b4NPP by at least three standard deviations, which equated to approximately 27% inhibition. These 80 compounds included a wide variety of small molecules, representing diverse therapeutic indications (Supplemental Table 1). Nucleoside analogues, diaryls, and polypharmacophore heterocyclics comprised the three largest classifications of molecules within this group, which is not surprising given that in general these compounds contain aromatic and heterocyclic ring structures that resemble the nitrogenous bases of purine and pyrimidines (Figure 5C). Also unsurprisingly, several commonly identified promiscuous or potentially nonspecific inhibitors were identified within the top 80 compounds.59,60 In summary, however, this diverse list of SAMHD1 inhibitors is suggestive of potential molecular scaffolds and potent pharmacophores around which additional chemical optimization can be performed in search of a robust SAMHD1 inhibitor.

Figure 5.

HTS results for inhibitors of SAMHD1 from the FDA-approved drug library. (A) Results from the HTS of FDA-approved compounds. The red line is the mean of the positive control samples (SAMHD1 and DMSO only) from all plates and represents full catalytic activity (fraction activity of 1.0). The blue line is the mean of the no enzyme control. Dashed lines represent ±three standard deviations of the positive control (σ = 0.9). (B) HTS results depicted as a histogram and highlighting compounds selected as top inhibitors for further dNTPase screening. (C) Molecular classification of the top 80 inhibitors of SAMHD1 catalytic activity as determined by HTS (full list provided in Supplemental Table 1). (D) Regression analysis comparing the inhibitory capacity of the top 80 SAMHD1 inhibitors of b4NPP hydrolysis as described in the HTS (x-axis) vs SAMHD1 inhibition in the presence of detergent (Tween 20) and activating nucleotides (25 μM GTP and 100 μM dATPαS) (y-axis). SAMHD1 inhibition by each compound was normalized to a positive control and divided by the concentration of each compound in the reaction mixture to give an inhibition value that was plotted. The strong correlation (R2 = 0.626) observed between the two assays supports the predictive capacity of the HTS. (E) Analysis similar to that performed in panel D, comparing normalized inhibition of SAMHD1 by each compound in the HTS (x-axis) and dNTPase (y-axis). The strong correlation (R2 = 0.584) further supports the predictive capacity of the HTS.

To more clearly assess the inhibitory potential of the top 80 hits from the HTS, their ability to inhibit SAMHD1 was investigated under two additional conditions. Given that the primary catalytically active configuration of SAMHD1 is a tetramer, it was important to determine that inhibition of the monomer in the HTS would correspond to a similar effect on the tetrameric species. A single plate containing all 80 top hits was prepared, and the b4NPP assay was repeated in the presence of the potential inhibitors with and without activating nucleotides (25 μM GTP and 100 μM dATPαS) to drive tetramer formation and a detergent (0.025% Tween 20) to mitigate nonspecific inhibitory effects from compound aggregation. While the reaction with activating nucleotides proceeded at a slower rate, a regression analysis of the inhibition of SAMHD1 activity relative to the internal positive control (SAMHD1 and DMSO only) and normalized by compound concentration revealed a strong correlation between the inhibition of SAMHD1 by a specific compound under both sets of conditions (R2 = 0.626) (Figure 5D).

In a second follow-up assay, the inhibitory potential of the top 80 HTS hits was determined by measuring SAMHD1 dNTPase activity on a deoxynucleoside substrate under conditions where enzyme tetramerization occurs.6,25 These reactions used MgCl2 instead of MnCl2 as the activating cation, and the reaction was initiated through the addition of 500 μM dGTP, which served as both the SAMHD1 activator and the substrate. The formation of dG was measured by HPLC to quantitate the reaction progress. A regression analysis comparing the effect of each putative inhibitor on SAMHD1 activity in the dNTPase and HTS assays revealed a moderately strong correlation (R2 = 0.584) when normalized by the molar concentration of the compound in the reaction (Figure 5E) and thus supports the utility of the HTS in identifying lead compounds capable of inhibiting SAMHD1 activity against its endogenous substrate. Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that inhibition of the Mn2+-activated monomer represents a good proxy model for inhibition of tetrameric SAMHD1 and that the HTS exhibits a predictive capability for identifying potential inhibitors of SAMHD1 dNTPase activity for further study.

Lastly, a modified version of the dNTPase assay was used to test five compounds that appeared to significantly enhance SAMHD1 activity in the HTS. SAMHD1 and the experimental compound (at either 100 μM or 1 mM) were combined in solution, and then 500 μM dATP was added to initiate the reaction. No SAMHD1 catalytic activity was observed using any of these compounds (data not shown), and we therefore concluded that the observed increase in absorbance in the HTS for these represented an artifact of the experimental conditions.

Validation of Top Hits Reveals Compounds with Micromolar Inhibition of SAMHD1 dNTPase Activity.

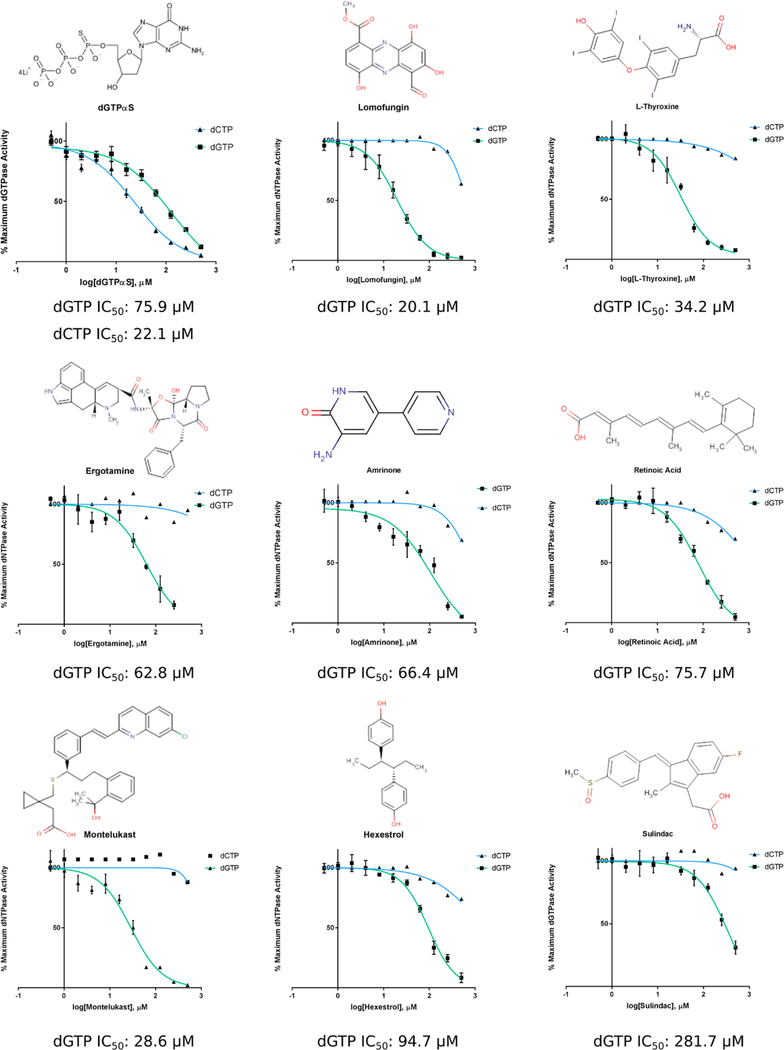

The top 30 SAMHD1 dGTPase inhibitors were further subjected to dose–response analysis to more rigorously interrogate their inhibitory properties. A persistent challenge encountered with high-throughput screens and associated orthogonal assays is the identification of nonspecific inhibitors that inactivate enzymes through a variety of mechanisms, including aggregation into colloidal particles, redox cycling, metal chelation, and covalent modification.61,62 In an effort to mitigate the effect of nonspecific inhibitors, SAMHD1 dose–response assays included increased amounts of reducing agent, BSA, and a small amount of non-ionic detergent (0.025% Tween 20) added to the reaction buffer.63,64 Additionally, 10× inhibitor stocks were made by serial dilution in 100% DMSO to enhance compound solubility. The final reaction concentration of 10% DMSO did not significantly alter SAMHD1 activity. The top 30 compounds were repurchased and prepared from powder, where possible, and tested for their ability to inhibit SAMHD1 catalysis across concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 500 μM. Either dGTP or dCTP (150 μM) was used as the SAMHD1 substrate. This concentration of dNTP substrate is in the proximity of the SAMHD1 KM but still enables accurate measurement of the initial reaction velocity.

The results of these experiments revealed that the inhibitory potential of several compounds identified in previous screens was either severely diminished or abolished completely under the more stringent conditions (Supplemental Table 2). Additionally, several other top hits exhibited very shallow or steep dose–response curves (Hill coefficient of <0.5 or >1.5), or non-zero baselines, all of which may be indicative of nonspecific enzyme inhibition.65,66 Many compounds, however, retained their inhibitory capacity, and eight compounds specifically (Lomofungin, L-Thyroxine, Ergotamine, Amrinone,retinoic acid, Montelukast, Hexestrol, and Sulindac) exhibited promising characteristics of micromolar IC50 values and Hill slopes approximating 1 (Figure 6). It should be noted that the inhibitory activity was explicitly evident only when using dGTP as both the activator and the substrate within the tested concentration range. Minimal inhibition of preactivated SAMHD1 dCTPase activity was observed except by the known SAMHD1 inhibitor dGTPαS. This may be due in part to the condensed and highly specific active site pocket of SAMHD1 that occurs upon formation of the tetramer. Alternatively, it may suggest inhibition of SAMHD1 by these compounds at sites other than the active site. Docking simulations were performed for each compound to estimate how they might bind in the active site, and a corresponding ΔG for the lowest-free energy pose was computationally calculated (Figure S4). On the basis of the simulations, each compound could be accommodated by the active site with free energy values roughly equivalent to those of endogenous SAMHD1 dNTP substrates. In summary, these data represent the discovery of previously unidentified small molecule inhibitors of SAMHD1 activity in vitro. Their identification validates the HTS as a lead generator for SAMHD1 inhibitors and presents multiple unique chemical scaffolds for further study, validation, and optimization.

Figure 6.

Top hits inhibit SAMHD1 dNTPase activity at micromolar concentrations. Dose–response curves of SAMHD1 activity in the presence of increasing concentrations of inhibitors. SAMHD1 activity was tested against both dGTP (green; n = 3) and dCTP (blue; n = 1). dGTPαS served as a positive control for inhibition

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the development and validation of a direct and simple HTS assay for measuring SAMHD1 catalytic activity using the compound b4NPP and Mn2+ as the activating divalent cation. b4NPP contains a phosphodiester bond that mimics the natural substrate of SAMHD1 and when cleaved results in a colorimetric transformation that can be read spectrophotometrically. b4NPP has been extensively reported as a substrate for phosphodiesterases, nucleases, and HD domain-containing enzymes similar to SAMHD1 when activated with Mn2+. Perhaps one of the more intriguing discoveries presented in this study is the ability of SAMHD1 to be catalytically active as a monomer when Mn2+ is the activating cation. While this finding was an important factor in optimizing our HTS, it also generates myriad questions about the nature and circumstances of divalent cation usage by SAMHD1 in vivo. If SAMHD1 tetramerization is not required for dNTP hydrolysis, there are major implications for our understanding of SAMHD1’s role in nucleotide homeostasis and innate immunity.

Optimization and validation of the b4NPP–SAMHD1 assay revealed conventional Michaelis–Menten kinetics and established that hydrolysis of b4NPP occurs in a metal-dependent manner using SAMHD1 active site chemistry. Subsequent experiments, including a secondary screen of HTS-identified inhibitors against SAMHD1 dGTPase activity, verified that the ability of SAMHD1 to hydrolyze b4NPP in the presence of Mn2+ serves as a robust proxy for its innate Mg2+-activated dNTPase catalytic activity. With a moderately strong correlation (R2 = 0.584), these data demonstrate the utility of the b4NPP–SAMHD1 assay as an effective method for screening chemical libraries and identifying lead compounds for continued investigation as potential inhibitors of SAMHD1 catalytic activity.

The b4NPP–SAMHD1 assay as described within this study does possess several potential mechanistic and functional limitations that must be considered when interpreting results. Because of the complex activation sequence of SAMHD1, in which activating nucleotide triphosphates drive conformational shifts that stabilize the catalytically competent tetramer, it may be possible that the Mn2+-activated monomeric species utilized in the b4NPP assay does not completely capture the highly specific active site architecture of the physiologically relevant enzyme. This, in turn, may result in an increase in the number of false positives (compounds that can inhibit b4NPP hydrolysis but not dNTPase activity) or at least an enhanced perception of inhibitor potency and could partially explain the limited dCTPase inhibition observed during dose–response experiments using the preactivated enzyme. Remediation of this incongruity may be resolved through the addition of activating nucleotides to the HTS to preform the SAMHD1 tetramer. The data reveal that despite a diminished active site affinity for b4NPP, tetrameric SAMHD1 retains the capacity to hydrolyze b4NPP, albeit less efficiently. It is not necessarily evident, however, that formation of the tetramer would provide significant predictive benefits in relation to lead generation. A comparison of the inhibition of SAMHD1 by the top 80 compounds from the HTS in the presence (tetramer) or absence (monomer) of activating nucleotides exhibited a strong correlation (R2 = 0.626) when normalized to their respective positive controls. In addition, any incremental benefit in predictive capacity would need to be weighed against the added cost of additional reagents when considered on a large scale.

The presence of indiscriminate inhibitors represents a second potential limitation of this assay and is a problem that is endemic to almost all high-throughput drug discovery efforts. These broad spectrum inhibitors, termed PAINS (pan assay interference compounds), can interfere with enzyme activity through a variety of nonspecific mechanisms such as aggregation, redox cycling, metal chelation, and covalent modification.61,62 To protect against the effects of nonspecific inhibition, various strategies can be applied, including the addition of small amounts of detergent, reducing agents, and BSA to the reaction mixture. While the b4NPP–SAMHD1 HTS is capable of accommodating the addition of these reagents and still generating a replicable signal, for the purposes of this study a minimal set of components was elected for the HTS. Consideration of indiscriminate inhibition was reserved for an orthogonal dGTPase screen and subsequent dose–response experiments performed using the top hits from the HTS.

Results from the dose–response assays, performed using the 30 most potent inhibitors of SAMHD1 dGTPase activity, are instructive for further validating promising inhibitory compounds. Given that competitive inhibition at a single active site invariably results in a Hill coefficient of 1, compounds exhibiting a shallow (HC < 0.5), steep (HC > 1.5), or nonzero baseline, dose–response curves were excluded from the final list of top inhibitors. It is again worth mentioning that the complex mechanism of SAMHD1 activation, in which two activating nucleotides must bind at distinct regulatory sites before catalysis is possible, does not enable us to immediately preclude compounds with Hill coefficients that are not approximately 1 from being legitimate SAMHD1 inhibitors. Compounds may be interacting with either or both of the regulatory sites, or there may be a cooperative effect to inhibiting a single active site on a SAMHD1 tetramer. Any of these effects would make the interpretation of a Hill coefficient difficult.

Following the dose–response analysis, eight compounds retained the capacity to inhibit SAMHD1 activity and exhibited IC50 values of <250 μM and Hill coefficients between 0.5 and 1.5. These compounds (Lomofungin, L-Thyroxine, Ergotamine, Amrinone, retinoic acid, Montelukast, Sulindac, and Hexestrol) generally contain aromatic and heterocyclic ring structures that resemble the nitrogenous bases of purine and pyrimidines. Despite these common structural features, they are chemically distinct as determined by their two-dimensional molecular fingerprints (all Tanimoto coefficients of ≤0.62) and displayed a diversity of therapeutic targets and indications. As indicated by the docking simulations, it is likely that the ring structures are accommodated by the SAMHD1 active site, and the various substituents and pharmacophores stabilize the compound binding through an enhanced network of weak interactions. The diversity of molecular scaffolds, therapeutic indications, and R groups presents promising opportunities and instructive guidance for future chemical optimization strategies. Additionally, although the data were not reported in this study, several NAATs, including Penciclovir (PubChem CID 4725), Pentoxifylline (PubChem CID 4740), and Capecitabine (PubChem CID 60953), demonstrated moderate SAMHD1 inhibition (~25%) in dose–response dNTPase assays at the highest concentrations tested (500 μM). These NAATs represent an additional molecular scaffold for optimization and have the added benefit of closely resembling the natural substrate of SAMHD1.

The highlighted top eight compounds, in addition to the other identified compounds that do not possess inhibitory profiles that are quite as potent, represent previously unidentified inhibitors of SAMHD1. Their discovery as potent inhibitors of SAMHD1 catalytic activity utilizing a novel and direct HTS further underscores the utility of the assay described in this study and the need to screen larger compound libraries. While further validation of the top hits is necessary to comprehensively characterize the nature of their SAMHD1 inhibition, including mechanism of action studies, crystal structures, and ultimately a cell-based assay, our results represent an encouraging step toward the realization of a robust small molecule inhibitor of SAMHD1 that will have important therapeutic and research applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Daniel Harki and Terry Smalley for chemistry consultation and helpful discussion and Dr. Fred Salsbury for help with molecular docking. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the work of Dr. Paul Holland for early SAMHD1 studies with the b4NPP compound.

Funding

This work has been supported through funding from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 GM108827 to T.H. and R01 GM110734 to F.W.P. and T32 GM095440 support for C.H.M.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- Ara-C

cytarabine

- b4NPP

bis(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DH

hydrodynamic diameter

- dATPαS

deoxyadenosine triphosphate α S

- dGTPαS

deoxyguanosine triphosphate α S

- dNTP

deoxynucleoside triphosphate

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HTS

high-throughput screen

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- NAAT

nucleotide analogue antimetabolite therapeutic

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- TREX1

three prime exonuclease 1

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01038.

Supplementary data and controls for activity assays as well as docking simulations (PDF)

REFERENCES

- 1.Rampazzo C, Miazzi C, Franzolin E, Pontarin G, Ferraro P, Frangini M, Reichard P, and Bianchi V (2010) Regulation by degradation, a cellular defense against deoxyribonucleotide pool imbalances. Mutat. Res, Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen 703, 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathews CK (2014) Deoxyribonucleotides as genetic and metabolic regulators. FASEB J. 28, 3832–3840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane AN, and Fan TW-M (2015) Regulation of mammalian nucleotide metabolism and biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 2466–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauney CH, and Hollis T (2018) SAMHD1: Recurring roles in cell cycle, viral restriction, cancer, and innate immunity. Autoimmunity 51, 96–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aravind L, and Koonin EV (1998) The HD domain defines a new superfamily of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci 23, 469–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell RD, Holland PJ, Hollis T, and Perrino FW (2011) Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome gene and HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase. J. Biol. Chem 286, 43596–43600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstone DC, Ennis-Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, Groom HCT, Rice GI, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Kelly G, Haire LF, Yap MW, de Carvalho LPS, Stoye JP, Crow YJ, Taylor IA, and Webb M (2011) HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 480, 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunz BA (1988) Mutagenesis and deoxyribonucleotide pool imbalance. Mutat. Res., Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen 200, 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohnken R, Kodigepalli KM, and Wu L (2015) Regulation of deoxynucleotide metabolism in cancer: novel mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Mol. Cancer 14, 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kretschmer S, Wolf C, Konig N, Staroske W, Guck J, Hausler M, Luksch H, Nguyen L.a Kim B, Alexopoulou D, Dahl A, Rapp A, Cardoso MC, Shevchenko A, and Lee-Kirsch MA (2015) SAMHD1 prevents autoimmunity by maintaining genome stability. Ann. Rheum. Dis 74, e17–e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Ayinde D, Logue EC, Dragin L, Bloch N, Maudet C, Bertrand M, Gramberg T, Pancino G, Priet S, Canard B, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Transy C, Landau NR, Kim B, and Margottin-Goguet F (2012) SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat. Immunol 13, 223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, ChableBessia C, Ségéral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, and Benkirane M (2011) SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 474, 654–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, KesikBrodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, and Skowronski J (2011) Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature 474, 658–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gramberg T, Kahle T, Bloch N, Wittmann S, Müllers E, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Kim B, Lindemann D, and Landau NR (2013) Restriction of diverse retroviruses by SAMHD1. Retrovirology 10, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollenbaugh JA, Gee P, Baker J, Daly MB, Amie SM, Tate J, Kasai N, Kanemura Y, Kim D-H, Ward BM, Koyanagi Y, and Kim B (2013) Host Factor SAMHD1 Restricts DNA Viruses in Non-Dividing Myeloid Cells. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim B, Nguyen LA, Daddacha W, and Hollenbaugh JA (2012) Tight Interplay among SAMHD1 Protein Level, Cellular dNTP Levels, and HIV-1 Proviral DNA Synthesis Kinetics in Human Primary Monocyte-derived Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem 287, 21570–21574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franzolin E, Pontarin G, Rampazzo C, Miazzi C, Ferraro P, Palumbo E, Reichard P, and Bianchi V (2013) The deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 is a major regulator of DNA precursor pools in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 14272–14277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kodigepalli KM, Li M, Liu S-L, and Wu L (2017) Exogenous expression of SAMHD1 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-derived HuT78 cells. Cell Cycle 16, 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coquel F, Silva M-J, Técher H, Zadorozhny K, Sharma S, Nieminuszczy J, Mettling C, Dardillac E, Barthe A, Schmitz A-L, Promonet A, Cribier A, Sarrazin A, Niedzwiedz W, Lopez B, Costanzo V, Krejci L, Chabes A, Benkirane M, Lin Y-L, and Pasero P (2018) SAMHD1 acts at stalled replication forks to prevent interferon induction. Nature 557, 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daddacha W, Koyen AE, Bastien AJ, Head PE, Dhere VR, Nabeta GN, Connolly EC, Werner E, Madden MZ, Daly MB, Minten EV, Whelan DR, Schlafstein AJ, Zhang H, Anand R, Doronio C, Withers AE, Shepard C, Sundaram RK, Deng X, Dynan WS, Wang Y, Bindra RS, Cejka P, Rothenberg E, Doetsch PW, Kim B, and Yu DS (2017) SAMHD1 Promotes DNA End Resection to Facilitate DNA Repair by Homologous Recombination. Cell Rep. 20, 1921–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu C-F, Wei W, Peng X, Dong Y-H, Gong Y, and Yu XFXF (2015) The mechanism of substrate-controlled allosteric regulation of SAMHD1 activated by GTP. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 71, 516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji X, Tang C, Zhao Q, Wang W, and Xiong Y (2014) Structural basis of cellular dNTP regulation by SAMHD1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E4305–E4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen EC, Seamon KJ, Cravens SL, and Stivers JT (2014) GTP activator and dNTP substrates of HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 generate a long-lived activated state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E1843–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt S, Schenkova K, Adam T, Erikson E, LehmannKoch J, Sertel S, Verhasselt B, Fackler OT, Lasitschka F, and Keppler OT (2015) SAMHD1’s protein expression profile in humans. J. Leukocyte Biol 98, 5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauney CH, Rogers LC, Harris RS, Daniel LW, Devarie-Baez NO, Wu H, Furdui CM, Poole LB, Perrino FW, and Hollis T (2017) The SAMHD1 dNTP Triphosphohydrolase Is Controlled by a Redox Switch. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 27, 1317–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadao A, Laguette N, and Benkirane M (2013) Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by Cyclin A2/ CDK1 Regulates Its Restriction Activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep. 3, 1036–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aye Y, Li M, Long MJC, and Weiss RS (2015) Ribonucleotide reductase and cancer: biological mechanisms and targeted therapies. Oncogene 34, 2011–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker WB (2009) Enzymology of purine and pyrimidine antimetabolites used in the treatment of cancer. Chem. Rev 109, 2880–2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rampazzo C, Tozzi MG, Dumontet C, and Jordheim LP (2016) The druggability of intracellular nucleotide-degrading enzymes. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 77, 883–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amie SM, Daly MB, Noble E, Schinazi RF, Bambara RA, and Kim B (2013) Anti-HIV host factor SAMHD1 regulates viral sensitivity to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors via modulation of cellular deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) levels. J. Biol. Chem 288, 20683–20691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollenbaugh JA, Schader SM, Schinazi RF, and Kim B (2015) Differential regulatory activities of viral protein X for anti-viral efficacy of nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in monocytederived macrophages and activated CD4+ T cells. Virology 485, 313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballana E, Badia R, Terradas G, Torres-Torronteras J, Ruiz A, Pauls E, Riveira-Muñoz E, Clotet B, Martí R, and Esté JA (2014) SAMHD1 specifically affects the antiviral potency of thymidine analog HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 58, 4804–4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ordonez P, Kunzelmann S, Groom HCT, Yap MW, Weising S, Meier C, Bishop KN, Taylor IA, and Stoye JP (2017) SAMHD1 enhances nucleoside-analogue efficacy against HIV-1 in myeloid cells. Sci. Rep 7, 42824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollenbaugh JA, Shelton J, Tao S, Amiralaei S, Liu P, Lu X, Goetze RW, Zhou L, Nettles JH, Schinazi RF, and Kim B (2017) Substrates and Inhibitors of SAMHD1. PLoS One 12, e0169052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herold N, Rudd SG, Sanjiv K, Kutzner J, Bladh J, Paulin CBJ, Helleday T, Henter J-I, and Schaller T (2017) SAMHD1 protects cancer cells from various nucleoside-based antimetabolites. Cell Cycle 16, 1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herold N, Rudd SG, Sanjiv K, Kutzner J, Myrberg IH, Paulin CBJ, Olsen TK, Helleday T, Henter J-I, and Schaller T (2017) With me or against me: Tumor suppressor and drug resistance activities of SAMHD1. Exp. Hematol 52, 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider C, Oellerich T, Baldauf H-M, Schwarz S-M, Thomas D, Flick R, Bohnenberger H, Kaderali L, Stegmann L, Cremer A, Martin M, Lohmeyer J, Michaelis M, Hornung V, Schliemann C, Berdel WE, Hartmann W, Wardelmann E, Comoglio F, Hansmann M-L, Yakunin AF, Geisslinger G, Ströbel P, Ferreirós N, Serve H, Keppler OT, and Cinatl J(2017) SAMHD1 is a biomarker for cytarabine response and a therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Med 23, 250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herold N, Rudd SG, Ljungblad L, Sanjiv K, Myrberg IH, Paulin CBJ, Heshmati Y, Hagenkort A, Kutzner J, Page BDG, Calderón-Montaño JM, Loseva O, Jemth A-S, Bulli L, Axelsson H, Tesi B, Valerie NCK, Höglund A, Bladh J, Wiita E, Sundin M, Uhlin M, Rassidakis G, Heyman M, Tamm KP, Warpman-Berglund U, Walfridsson J, Lehmann S, Grandér D, Lundbäck T, Kogner P, Henter J-I, Helleday T, and Schaller T.¨ (2017) Targeting SAMHD1 with the Vpx protein to improve cytarabine therapy for hematological malignancies. Nat. Med 23, 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudd SG, Schaller T, Herold N, Rudd SG, Schaller T, Herold N, Rudd SG, Schaller T, Rudd SG, and Herold N (2017) SAMHD1 is a barrier to antimetabolite-based cancer therapies. Mol. Cell. Oncol 4, e1287554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pai C, and Kearsey S (2017) A Critical Balance: dNTPs and the Maintenance of Genome Stability. Genes 8, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mathews CK (2015) Deoxyribonucleotide metabolism, mutagenesis and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 528–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartkova J, Horejsí Z, Koed K, Krämer A, Tort F, Zieger K, Guldberg P, Sehested M, Nesland JM, Lukas C, Ørntoft T, Lukas J, and Bartek J (2005) DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature 434, 864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Montfoort N, Olagnier D, and Hiscott J (2014) Unmasking immune sensing of retroviruses: Interplay between innate sensors and host effectors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 25, 657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maelfait J, Bridgeman A, Benlahrech A, Cursi C, and Rehwinkel J (2016) Restriction by SAMHD1 Limits cGAS/STING-Dependent Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses to HIV-1. Cell Rep 16, 1492–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manel N, Hogstad B, Wang Y, Levy DE, Unutmaz D, and Littman DR (2010) A cryptic sensor for HIV-1 activates antiviral innate immunity in dendritic cells. Nature 467, 214–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bregnard C, Benkirane M, and Laguette N (2014) DNA damage repair machinery and HIV escape from innate immune sensing. Front. Microbiol 5, 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S, Bonifati S, Qin Z, St. Gelais C, Kodigepalli KM, Barrett BS, Kim SH, Antonucci JM, Ladner KJ, Buzovetsky O, Knecht KM, Xiong Y, Yount JS, Guttridge DC, Santiago ML, and Wu L (2018) SAMHD1 suppresses innate immune responses to viral infections and inflammatory stimuli by inhibiting the NF-κB and interferon pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, E3798–E3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnold LH, Kunzelmann S, Webb MR, and Taylor IA (2015) A Continuous Enzyme-Coupled Assay for Triphosphohydrolase Activity of HIV-1 Restriction Factor SAMHD1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 59, 186–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seamon KJ, and Stivers JT (2015) A High-Throughput Enzyme-Coupled Assay for SAMHD1 dNTPase. J. Biomol. Screening 20, 801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strovel J, Sittampalam S, Coussens NP, Hughes M, Inglese J, Kurtz A, Andalibi A, Patton L, Austin C, Baltezor M, Beckloff M, Weingarten M, and Weir S (2016) Early Drug Discovery and Development Guidelines: For Academic Researchers, Collaborators, and Start-up Companies. Assay Guidance Manual, Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J-H (1999) A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J. Biomol. Screening 4, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trott O, and Olson AJ (2010) AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem, 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, and Ferrin TE (2004) UCSF Chimera: A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huynh TN, Luo S, Pensinger D, Sauer J-D, Tong L, and Woodward JJ (2015) An HD-domain phosphodiesterase mediates cooperative hydrolysis of c-di-AMP to affect bacterial growth and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, E747–E756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rao F, Qi Y, Murugan E, Pasunooti S, and Ji Q (2010) 2′,3′-cAMP hydrolysis by metal-dependent phosphodiesterases containing DHH, EAL, and HD domains is non-specific: Implications for PDE screening. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 398, 500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Späth B, Settele F, Schilling O, D’Angelo I, Vogel A, Feldmann I, Meyer-Klaucke W, and Marchfelder A (2007) Metal Requirements and Phosphodiesterase Activity of tRNase Z Enzymes †. Biochemistry 46, 14742–14750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keppetipola N, and Shuman S (2008) A Phosphate-binding Histidine of Binuclear Metallophosphodiesterase Enzymes Is a Determinant of 2′,3′-Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterase Activity. J. Biol. Chem 283, 30942–30949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keppetipola N, and Shuman S (2007) Characterization of the 2′,3′ cyclic phosphodiesterase activities of Clostridium thermocellum polynucleotide kinase-phosphatase and bacteriophage phosphatase. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 7721–7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilberg E, Jasial S, Stumpfe D, Dimova D, and Bajorath J (2016) Highly Promiscuous Small Molecules from Biological Screening Assays Include Many Pan-Assay Interference Compounds but Also Candidates for Polypharmacology. J. Med. Chem 59, 10285–10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schorpp K, Rothenaigner I, Salmina E, Reinshagen J, Low T, Brenke JK, Gopalakrishnan J, Tetko IV, Gul S, and Hadian K (2014) Identification of Small-Molecule Frequent Hitters from AlphaScreen High-Throughput Screens. J. Biomol. Screening 19, 715–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baell JB, and Nissink JWM (2018) Seven Year Itch: PanAssay Interference Compounds (PAINS) in 2017 - Utility and Limitations. ACS Chem. Biol 13, 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dahlin JL, Nissink JWM, Strasser JM, Francis S, Higgins L, Zhou H, Zhang Z, and Walters MA (2015) PAINS in the assay: Chemical mechanisms of assay interference and promiscuous enzymatic inhibition observed during a sulfhydryl-scavenging HTS. J. Med. Chem 58, 2091–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feng BY, and Shoichet BK (2006) A detergent-based assay for the detection of promiscuous inhibitors. Nat. Protoc 1, 550–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Acker MG, and Auld DS (2014) Considerations for the design and reporting of enzyme assays in high-throughput screening applications. Perspect. Sci 1, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shoichet BK (2006) Interpreting steep dose-response curves in early inhibitor discovery. J. Med. Chem 49, 7274–7277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prinz H (2010) Hill coefficients, dose-response curves and allosteric mechanisms. J. Chem. Biol 3, 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.