Abstract

There is increasing evidence that women are receiving a traumatic brain injury (TBI) during episodes of intimate partner violence (IPV), but little qualitative research exists around how surviving this experience impacts the lives of women. Primary and secondary data (N = 19) were used with a constructivist grounded theory approach to explore the lives of women aged 18 to 44 years, who were living with a TBI from IPV. Women described multiple aspects of living in fear that shaped their daily lives and ability to seek help and access resources. The central process of prioritizing safety emerged, with salient dimensions of maintaining a present orientation, exhibiting hyperprotection of children, invoking isolation as protection, and calculating risk of death. These findings add to the growing body of knowledge that women living with IPV are at high risk for receiving a TBI and are therefore a subgroup in need of more prevention and treatment resources.

Keywords: domestic, abuse, violence against women, structural violence, brain injury, community and public health, qualitative;grounded theory, situational analysis, United States

The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey estimates that more than one in three women will experience intimate partner violence (IPV) in their lifetimes (Black et al., 2011). IPV is defined as behaviors that are intended to exert power and control over another individual and includes physical, sexual, verbal, emotional, and financial abuse and or/stalking. Men can be victims of abuse, but IPV occurs more often when a man is attempting to control his female partner, whether she is a wife, girlfriend, or significant other (Black et al., 2011). IPV has long-term negative health consequences for survivors, even after the abuse has ended (Campbell, 2002).

Women who receive a traumatic brain injury (TBI) from IPV are receiving more attention as awareness of head injury, including TBI and concussion, is growing in popular culture but underreporting of both TBI and IPV make this a difficult area of study. Very little is known about the episodes when a TBI from IPV is inflicted, challenges to accessing women’s shelters and resources for IPV after receiving a TBI, and the long-term health consequences of TBI from IPV (Corrigan, Wolfe, Mysiw, Jackson, & Bogner, 2003; Davis, 2014; St Ivany & Schminkey, 2016).

Recent studies have demonstrated IPV as a risk factor for TBI. One study found women living with IPV 7 times more likely (odds ratio [OR] = 7.21, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [2.79, 18.61], p < .001) than women who are not living with IPV to receive a head injury with loss of consciousness (Anderson, Stockman, Sabri, Campbell, & Campbell, 2015). Zieman, Bridwell, and Cardenas (2017) found 101 out of 115 (88%) of women receiving medical treatment for TBI from IPV reporting more than one head injury with 93 of 115 (81%) reporting a history of loss of consciousness associated with their injuries, but only 24 women (21%) sought medical help at the time of injury.

Philosophical and Theoretical Underpinnings

Intersectionality is “the critical insight that race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, ability, and age operate not as unitary, mutually exclusive entities, but as reciprocally constructing phenomena that in turn shape complex social inequalities” (Collins, 2015, p. 2). It is an important public health concept to aide in understanding how social identities interact and overlap to produce health inequalities (Bowleg, 2012). Kelly (2011) defined feminist intersectionality as a body of knowledge that seeks to explore how the characteristics of individuals and groups in various social positions interact to result in inequitable access to resources that have negative effects on health and well-being. A feminist intersectional perspective guided both data collection and analysis to think about the ways that multiple social identities in the lives of women overlap to create challenges and barriers in seeking resources, helped with forming interview questions and guided analysis.

Grounded theory has its theoretical roots in symbolic interactionism (SI) and when used together the two constitute a theory/methods package. Traditional views of SI by Blumer and Mead are founded on three basic principles: that people’s actions toward things are “based on the meanings that these things have for them,” that these meanings come from interactions, and that these meanings can be created and changed through interactions and interpretations of individuals as they happen (Pawluch & Neiterman, 2010, p. 174). A postmodern, constructivist view of SI, and the one taken in this study, was SI is the way in which we all make meaning in our lives (Clarke, Friese, & Washburn, 2017). Doing constructivist grounded theory means studying how and why participants create meanings that lead to actions in situations (Charmaz, 2014). Constructivist grounded theory is rooted in postmodernism by believing that knowledge is based on a situation and the researcher’s interpretation of that situation, rather than a positivist approach of a researcher remaining objective or describing a reality (Corbin, 2009). Grounded theory after the postmodern turn emphasizes partial perspectives and situated knowl edge as well as knowledge that is constantly evolving with exposure to new situations (Clarke et al., 2017; Corbin, 2009).

The purpose of this study was to explore the nature and context of women’s lives who are living with the con sequences of a head injury from IPV and to gain insight into how it impacts their lives and relationships with their families and abuser(s). Specific aims of the study were as follows: (a) to describe the experience and context of the lives of women who report passing out from being hit in the head during an episode of IPV, and (b) to explain how receiving a head injury from IPV impacts the lives of women, both in their relationships with the abuser, their families, and in the greater social context.

Materials and Methods

Design

We used a constructivist grounded theory approach that focuses on knowledge construction rather than applying existing knowledge to explore a problem. Intersectionality was a philosophical lens that guided initial analysis. Interviews with survivors of IPV were analyzed in an iterative and emergent process to explore the full range of variations in processes and experiences related to how women’s lives are impacted by experiencing a TBI during IPV (Charmaz, 2014; Clarke et al., 2017).

Participants

Data used for the study included primary and secondary data (N = 19). Purposive sampling included secondary data from the Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation Program (DOVE), a multistate randomized clinical trial conducted between 2006 and 2012 (Bullock and Sharps, NIH/NINR—R01 NR009093) that evaluated the effectiveness of an empowerment protocol within home visiting programs with low-income women who experienced IPV during pregnancy and postpartum (Sharps, Alhusen, Bullock, Bhandari, Ghazarian, Udo, & Campbell, 2013). Of the 239 total women, 21 answered yes to the question “Have you ever passed out from being hit in the head by your partner?” at some point during the study; 16 answered yes at baseline and five answered yes during the two-year timeframe of the study. Nine of the 21 women participated in one or more qualitative interviews over the two-year study duration for a total of 29 interviews and these interviews formed the database for secondary analysis.

Primary data collection occurred in mid-Atlantic region of the United States using flyers placed in women’s shelters, at bus stops and grocery stores, ads posted on Craigslist, and snowball sampling. Recruiting criteria were women between the ages of 18 and 45 years who self-reported passing out from being hit in the head. The recruitment ads did not mention IPV specifically to protect the safety of the women. Thirty-one women responded to the recruitment, 21 were ineligible because of head injury from a source that was not IPV such as car accident or sports. Ten women met eligibility criteria of head injury from IPV and agreed to participate in the study. Institutional review board approval was given for the collection of both primary and secondary data.

Sample Characteristics

Forty-one interviews from 19 participants were analyzed to explore the nature and context of how living with a head injury from IPV impacts their lives and relationships with their families and abuser(s). Participant ages ranged from 18 to 44 years to capture women who were currently experiencing IPV and those who had successfully navigated out of the relationship. Fifteen women were from urban and suburban areas of East Coast cities and four women were from a Midwestern state. Three women were employed full-time; the rest were unemployed or underemployed. Although no medical diagnosis was made for TBI, self-reporting of a loss of consciousness is indicative of a TBI (Ruff et al., 2009) and women described symptoms consistent with having a TBI such as migraines, problems with memory and concentration, and depression. During the interviews, some women described experiencing IPV from a dating relationship or from cohabitating with the abuser and being afraid or unable to get medical care. The interviewer had a list of resources for domestic violence and safety if necessary, but no women asked for these resources because they were no longer in an abusive relationship or were already in the women’s shelter. In three instances, an episode of TBI from IPV was the trigger for the women leaving the relationship to go to the women’s shelter.

Data Collection

Twenty-nine transcribed, deidentified interviews were transferred to the first author for analysis and coding of secondary data analysis (n = 9). The focus of the DOVE interviews was to understand the woman’s current life situation, family context and history of abuse, IPV experiences (including during pregnancy), and resources and barriers for getting help.

For primary data collection, one on one interviews were conducted by telephone because this was the participants’ preferred method rather than meeting in person (n = 10). These new interviews queried women about symptoms of head injury, a lifetime history of head injury, why they did or did not get medical treatment for the head injury, relationships with doctors and medical providers, and challenges of staying in a women’s shelter. After verbal consent, the interview was recorded with a digital recorder and transcribed verbatim by members of the study team and research assistants. Two women participated in follow up interviews for a total of 12 primary interviews. No demographic data were collected to protect the safety and confidentiality of the women. After each interview, the first author, Amanda St Ivany, wrote a memo including notes from the interview, reflexivity, developing concepts, and questions for future interviews. As analysis proceeded, theoretical verification shaped interviews by asking women to describe ways their symptoms of head injury impacted their daily lives and help-seeking behaviors, such as staying in a women’s shelter. Dedoose software was used for data management and organization. To track rigor, analytic and theoretical memos were written throughout data collection and analysis to track conceptual development. Qualitative peer debriefing was used through research groups and regular meetings with methods experts and content experts.

Analysis

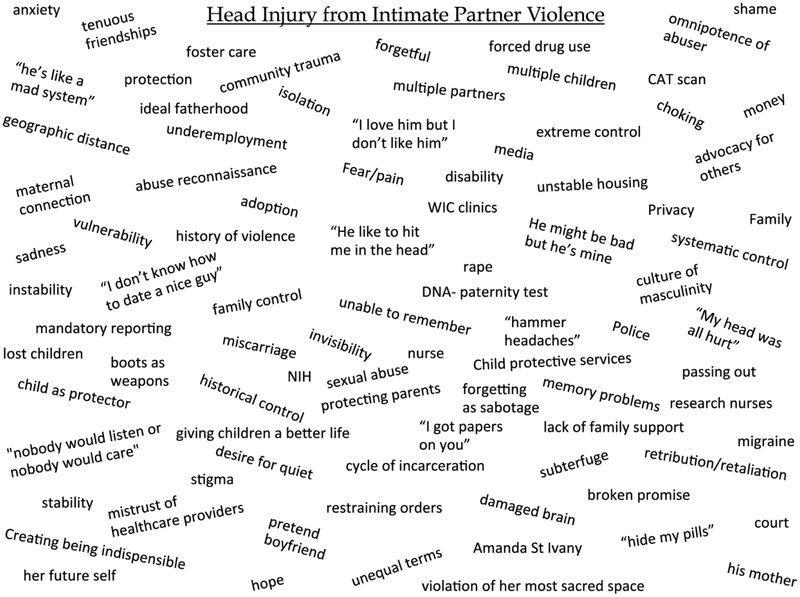

Data collection and analysis occur as an iterative process and the two are conducted simultaneously in constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The first phase of open coding used situational analysis, which treats the situation itself as the unit of analysis to understand the elements and relationships between the elements (Clarke et al., 2017). Situational maps were created early in the analytic process and revised after presenting at workshops and consultations with methods experts. Situational maps use the collective situation of receiving a head injury from IPV as the unit of analysis, rather than each individual woman’s experiences (see Figure 1 for situational map example). These situational maps were used as a complementary strategy to amplify coding and to open up the data, with codes placed on a messy map to layout all of the elements that might be involved in the situation. Memos were written after each mapping session to track analytic progress. These memos and maps were integrated into the coding to inform the central process (Clarke et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Situational map of head injury from IPV for first phase of analysis (n = 12).

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

The second phase of open coding merged codes to place them into categories while remaining open to developing concepts that emerged from the data and explored other analytic ideas in the data collection and analysis process (Charmaz, 2014). During this phase, the concept of structural violence was identified and defined for analysis as women described challenges to accessing health care and feeling like the health care environment would not keep them safe. The third phase of coding, axial coding, categorized the more salient codes and connected categories to make relationships. The interview guide was modified to challenge, verify, and enrich the categories during future interviews, including questions about trusting doctors, ways to make it easier to get medical care from the women’s shelter, and the process of pressing charges. Groups within the sample, such as women with children and women without children, were compared and contrasted to identify salient themes.

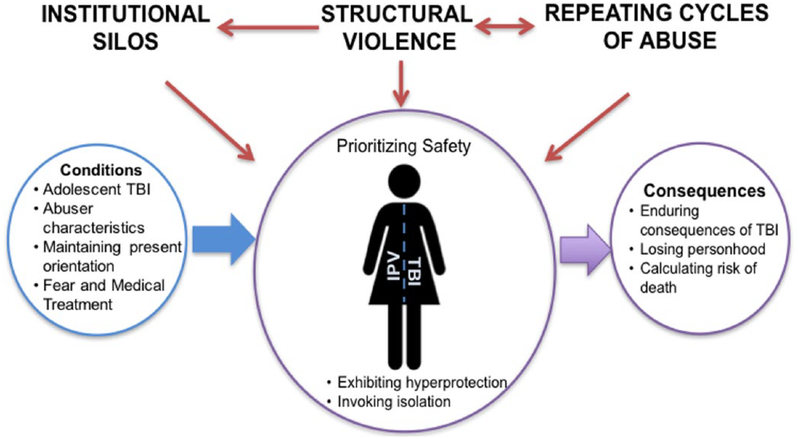

Theoretical coding organized conceptual codes and in vivo codes into a coherent analysis. Theoretical codes were grounded in the data and each was auditioned as central to the organization of an explanatory matrix that structured the salient categories as context, conditions, actions/interactions, and consequences (Kools, McCarthy, Durham, & Robrecht, 1996). The explanatory matrix that best fit the story of the data was selected to narrate the theory developed from the analysis (see Figure 2 for Explanatory Matrix).

Figure 2. Explanatory matrix.

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; TBI = traumatic brain injury.

Theoretical sampling was complete when the conceptual categories created could be fully described and used to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research area of head injury from IPV. Theoretical verification included Amanda St Ivany presenting early results on the concept of intersectionality at a women’s shelter and incorporating feedback from shelter workers and observations at the shelter into memos and analysis. Findings presented here offer a theoretical depiction of how experiencing a lifetime of abuse, control from institutions, and structural violence influence the feeling of living in fear and the actions women take to prioritize safety after receiving a probable TBI from IPV.

Findings

Women talked about interrelated components of experiencing instability in childhood, historical control from institutions such as foster care, structural violence, repeated cycles of abuse throughout their lives, and receiving head injuries from multiple sources. These factors are the foundation for the central perspective and grounded theory that we call living in fear and prioritizing safety after TBI from IPV (see Figure 2 for explanatory matrix outlining the central perspective and theory). When women decided to get help, such as medical care or going to a women’s shelter, they would prioritize safety while weighing the risks and benefits of options. Because they were unable to get resources that addressed both TBI and IPV, they would make their final decision based on maximizing their safety.

Central Perspective-Living in Fear and Prioritizing Safety After TBI From IPV

Context.

We define the concept of growing up with instability as described by the women as feeling neglected in childhood, being surrounded by a culture of drugs and alcohol, having an abusive father, and experiencing extreme child abuse and neglect and being placed in foster care. Women described their childhoods and adolescence as “rough” or “being something that no kid should experience.” Two different 39-year-old women describe their upbringing:

My dad beat my mom, and then they got a divorce, then I lost a brother, and then I … ran away with [the abuser] and he used to beat me and he used to hit me in my head.

I was taken from my mom because she abused me. She didn’t feed me. When I was taken at the age of 8 I weighed 40 pounds. So I had a rough upbringing. When I was taken I was in and out of foster homes, just switched all around. I never stayed in one place for more than a month so school was hard on me.

Women had lifetime histories of interacting with systems and organizations with rules that took away their autonomy in the form of imposing protection: foster care, child protective services, the police, jail, the military, and “shelter hopping.” One 36-year-old woman describes growing up in foster care. “We were born through foster homes. Me and my sisters, siblings … we were placed in shelters and stuff like that and there was a lot of violence.” This instability contributed to their vulnerability to enter into an abusive relationship. Many women were still experiencing unstable lives and trying to provide their children with a stable upbringing.

Structural violence.

Even though they did not use the term, women described the structural violence of the health care and legal systems and needing to know that their safety was a priority if they got medical treatment. Several women talked about not trusting doctors or not being sure the doctors would do what is best for them. One woman described her lifetime experiences with doctors:

I don’t trust any doctors really … ‘Cuz I feel like I’m wasting my time. That’s how they make me feel. I mean I’ve been in and out of hospitals my whole life, I’ve been seeing psychiatrists my whole life, and I’m 39 years old and I’m still the same. Living in fear.

Several women felt judged and stigmatized for IPV and experienced victim blaming in some interactions with medical professionals, police, and first responders. Other women said they did not disclose abuse because they did not want everyone to know their business. Women had long-term relationships with therapists, caseworkers, social workers, and psychiatrists. Some described good relationships with a therapist or a caseworker who was invested in their success, but most had experiences with therapists who just gave them a prescription for medication or described caseworkers who they perceived as trying to break up their families.

Because most of these women grew up in unstable home situations or foster care, they described wanting to provide stability for their children and recognized that pressing charges or getting medical care and having social services involved could result in losing their children. They all had mixed experiences with police involvement and felt like they could not be guaranteed safety if they pressed charges.

Some women filled out protective orders and described it as “easy” but no women had pressed charges; saying they did not have time, they could not or did not want to find him, or they felt sorry for him. One woman describes the police response when she was getting stitches after an episode of dating violence.

The police were like, well if you want to press charges, you have to go to courthouse yourself, I’m like you know what “XXXX you.” Excuse my language. I’m like yeah okay. Right after my 20 stitches, I’ll go—go into the courthouse, okay. I’ll put it on my to-do list, gotcha. That just made me feel like they weren’t really taking me seriously.

Some women were afraid of what would happen to them if they pressed charges. In several cases, the abusers had previously served sentences for domestic violence or femicide and started abusing the women when they were released. This made women feel that if they pressed charges and the abusers went to jail, they would retaliate when released. Even the women who had filed protective orders did not feel safe because the penalty for violation was not very severe and it only takes one violation to inflict serious harm.

Lack of overlapping resources for TBI from IPV.

From an institutional level, women expressed frustration that women’s shelters do not provide screening upon admission or referrals for head injury. One 22-year-old woman suggests increasing awareness of TBI from IPV during shelter admissions.

Ask them questions about how the fights went. Did they get hit in the head? Did they get stomped in the head; did they have any head trauma? And depending on how the person answers then some of them need a referral for a CAT scan and … some people don’t.

If they did get health care and disclose abuse, doctors and nurses “just gave them a number” but did not connect them to resources, which made them feel like they were navigating the process alone.

Conditions.

The conditions for women that contributed to the central process of living in fear and prioritizing safety were getting a TBI in adolescence, abuser characteristics, maintaining a present orientation, and fear and medical treatment. The abusers were described as dangerous men who inculcated a sense of fear in women. This contributes to the consequence of calculating risk of death because getting medical treatment would not provide protection from getting hit in the head again but almost always was perceived to put women at increased risk from the abusers.

Getting a TBI in adolescence.

Women in the primary data interviews all described experiencing some form of TBI in youth or adolescence from sports, abuse, or car accident that precipitated their TBI from IPV. A 20-year-old woman describes her abusive father who would repeatedly hit her in the head. “My father used to hit me in the head all the time … he would take his fist and punch me in my head or slap me in the back of head and stuff like that.” Another woman described getting in a car accident when she was in high school and going through three months of hospitalization followed by three months of rehab and having to relearn basic skills, such as talking.

Abuser characteristics.

The characteristics of the abusers play a large role in influencing women’s actions and interactions to prioritize safety. We call the process embodying patriarchy to capture the depth and complexity of these abusers who were described as large and dangerous men who instilled fear and had inflicted violence on many people. They were portrayed as deriving a valued identity from being dangerous men, expressing hypermasculinity, and previously killing or injuring other women. Several were members of biker gangs and many had served time in jail for assault.

One young woman describes the abuse the night she took her kids and went to the shelter:

It’s like he tried to kill me. He would take his fists and—and take his feet and keep kicking me and stomping me in my head. The reason why I ended up in the shelter is because he almost killed me. I actually blacked out for a little over an hour. I didn’t really remember anything. When I woke up there was blood all over the place just from [my] face … Blood all over the place because he stomped me in my head, in my face, everything.

A 36-year-old woman describes how she still lives with fear from her episode of dating violence:

He forced me into things that I didn’t want to do … punched me on my head, like I can still see it, I can still remember it with the pain, like I can’t even lay my head on the pillow because he punched me so many times in my head and pulled my hair. The thing is, it’s really like, it’s still stuck in my … it’s like, I wish, I’m getting medical treatment for it and like I’m scared to be around people.

Women described multiple episodes of IPV where the abusers would hit them in the head:

I was trying to get away … he pulled me back in the house and started beating me even more. He was stomping me in my head, kicking me in my face, punching me, slapping me, choking me, everything. It was just awful.

Three years ago … he took my head and kept hitting it on the wall, hitting it on the floor, hitting it on the wall, hitting it on the floor. And he just kept taking my head by the hair and hitting on the head, I mean hitting it on the floor.

These men were also described as coming from abusive homes, growing up on the streets, serving in the military, and having a suspected history of TBI. A 39-year-old woman who recently left her second abuser that hit her in the head describes both of them:

Their fathers both abused them as a child. My husband was hit so hard in the head, I think he was 3 years old; he was put in the hospital for a week ‘cause he had a concussion. So he was brought up in an abusive home as well as my son’s father.

Women needed a physical barrier to feel safe from these men and would call the police to intervene during a fight or move away to create physical distance. Some women felt safer when the abusers were in jail but were scared about when they would be released. One woman described her abuser as “getting what was coming to him” when he was murdered on the streets.

Maintaining a present orientation.

We define maintaining a present orientation as elements in women’s daily lives that force them to remain focused on the immediate situations and not able to plan for or envision the future. The context of growing up with instability continued into adulthood for many women and they discussed difficul ties finding stable employment and housing and having to give up previous jobs because their abusers could find them. Women experiencing extreme IPV or who had recently left abusive relationships were living in constant fear and making decisions on a day-by-day basis that impacted their safety and well-being.

Fear and medical treatment.

Women talked about being afraid to get medical treatment which has several dimensions: being afraid of the abusers’ actions, knowing something is wrong with them and not wanting to learn this truth, and feeling judged by health care workers. Because these abusers were dangerous men capable of inflicting harm, women were afraid that they would find them in the hospital or were afraid of retaliation if they sought medical care:

If I was just to go out and say look, [my man] did this and this, if I ever did that he would definitely … come back and try to either just get rid of me … I didn’t want the chance that [they would] find me dead in the woods or something like that.

The other element of fear was knowing that something is wrong, but not wanting to learn about permanent dam age and disability when they went to the doctor.

I’m scared for somebody to tell me, “Oh I have blood clots, my head inside is swollen,” or stuff like that … That’s why I never really told anybody in the shelter, or went to the doctor’s even though when I went to the shelter they knew about it. They told me I needed to go to the doctor’s right away but I never went because they might tell me something I don’t want to hear because I know there’s something wrong with me. I know I’m not normal after that. I know there’s something wrong with my head or my hearing. I don’t want them to tell me I’m going deaf or anything like that, you know.

Because of the broad spectrum of women’s experiences included in the study, a facilitating factor identified to getting medical treatment was having witnesses to the TBI from IPV (such as friends or spectators in a public place) and barriers to getting medical treatment included perceived compromising of the safety of herself and/or her children by seeking medical treatment.

Actions/interactions.

In response to the conditions and context of women’s lives, the central process that women engaged in was prioritizing safety. Safety in this sense means more than safety from the abuser; it is an expanded definition of safety that encompasses keeping families together, providing children with food and shelter, and trying to control and manage the influence of the institutions that would restrict women’s ability to decide how to keep themselves safe. Women recognized loss of autonomy when they entered into systems controlled by forces beyond their control and perceived that these systems cannot keep them safe with this expanded definition of safety.

Exhibiting hyperprotection of her children.

The abusers exhibited dangerous behavior such as stalking, arson, threatening to harm children, and forced sex to terrorize women, which often resulted in making protecting children a priority over getting medical care to treat injuries. Women made the choice to protect their children in the immediate moment to keep themselves and their children safe from harm inflicted by the abusers. Sometimes this manifested as not getting medical treatment to stay with the children and other times it meant taking the children and going to the women’s shelter.

Invoking isolation as protection.

Using isolation as a form of protection is another action women used to prioritize safety. Women talked about losing trust in men, cutting themselves off from friends and social circles, and not disclosing the IPV to family members to avoid placing their families at risk of harm from the abusers. They talked about not wanting to open themselves up to being abused again and the best way to do that was to keep everyone out. A 44-year-old woman describes trying to end the cycle of abuse by isolating herself and children:

I was just like finding myself going back into the same circle of things … I had to stop a lot of things and just get my life back on track. And I just had to remove myself from a lot of people and delete a lot of people from my buddy list. I just had to clean house and [shift] my priority for myself and my kids.

Consequences.

The consequences of prioritizing safety and living in fear were: enduring the consequences of TBI, losing personhood, and calculating risk of death. Women were afraid of taking actions to promote their health. Because of the dangerous nature of the abusers, women prioritized their safety in the moment and either stayed with the abuser because it is too dangerous to leave and/or they wanted to protect their children from being harmed. If women decided it was time to leave the relationship after getting hit in the head during IPV, they were more likely to go to the women’s shelter and not the hospital, even if the shelter recommended going to the hospital. This decision was directly related to their need to feel safe with the expanded definition of safety.

Enduring the consequences of TBI.

Because women made safety a priority, this sometimes meant they would not get medical attention or treatment for their probable TBIs. Even if they did get medical treatment, women still talked about living with neurological and mental health symptoms of TBI. They would survive extreme episodes of physical and sexual violence, prioritize their safety by going to the women’s shelter instead of the hospital, and then have to deal with the consequences of making that decision. This is best summarized by the in vivo code “I survived for this?”

Women described migraines lasting for days or months, unrelenting pain in their bodies (head, face, teeth, hands), insomnia followed by hyper somnolence, anxiety and depression that was heightened and intensified after the TBI from IPV, problems with memory, and difficulty finding or keeping a job.

Women said they felt damaged, not normal, and recognized their lost potential. During several interviews, some women said they realized they needed to see a neurologist to address their symptoms. Some described lost cognitive abilities such as feeling less smart and having trouble with memory and task management that was impacting their ability to keep a job. They discussed specific damaged parts, such as cracked teeth or scars on forehead, which would always impact people’s first impression of them in a negative way. These sentiments contribute to low feelings of self-esteem and self-worth, and hopelessness. Happiness was something that other people could experience but not them:

At 44 I can honestly say I … see all these happy couples and it hurts me because what makes them so special? [starting to cry] What do they have that I don’t? Why do I have to be abused? And it hurts! So I just, [crying] I just can’t, and I work every day and I don’t know what it means to be happy.

Calculating risk of death.

This consequence is related to the condition of maintaining a present orientation because women recognize that the abusers could have killed them and were still capable of hurting or killing them and considered this when deciding if they should get medical treatment. They calculated their risk of death in daily interactions and disclosed facing mortality in a very concrete way, saying “he almost killed me” or he could have killed me if he wanted to. A woman who has been in multiple abusive relationships and received probable TBIs from different abusers describes her fear of death.

I’ve had concussions. [The doctors] told me if I get hit again in my head really hard I could die. Because that’s how many concussions I’ve had over my lifetime. I don’t want to go back to my husband because I’m scared of him. I’m scared I’m going to just end up dead, period. If I get hit in the head again, you know … I just don’t know what to do.

Discussion

It is important to understand the complex situation of TBI from IPV and how women decide which actions to take based on elements of the entire situation. We believe this to be one of the first qualitative studies that explores the context of women’s lives when they are living with a probable TBI from IPV. This study verifies existing literature on health consequences of TBI from IPV in women: anxiety, depression, gastrointestinal disorders, stroke, sexually transmitted diseases, and heart disease (Campbell, 2002; Ford-Gilboe, Varcoe, Wuest, & Merritt-Gray, 2011; Kwako et al., 2011; Rich, 2014).

This study found similar findings of increased depression after TBI from IPV as Iverson and Pogoda (2015) but one important difference is that study found female veterans seek health care more after TBI from IPV than women not in the military. An important question to guide future research is what are differences in military and nonmilitary populations, such as access to health care, less isolation when living on a military base than in rural communities, and differences in living spaces such as more public living areas that decrease privacy.

The theory of prioritizing safety after TBI from IPV describes how this intersectionality influences the ability to seek resources to achieve optimal health for the women in the study. Calculating risk of death and maintaining a present orientation, experiencing housing instability, and living in fear forced each woman to make decisions on a day-by-day basis. The combination of neurological symptoms, mental health challenges, and using isolation as protection make it difficult to get and keep a job to bring the stability to her life that she needs. Women in this study struggle with the intersectionality of TBI and IPV as they access resources to address one or the other in systems that are not designed to address both.

The term structural violence was coined in the 1960s by Galtung et al. and has grown in usage and scope and is related to other terms such as structural determinants of health and patient engagement (Galtung, 1969). Farmer, Nizeye, Stulac, and Keshavjee (2006) expanded the original definition to talk about structural violence as “social arrangements that put individuals and populations in harm’s way” (p. e449). We define structural violence as the ways that women are kept from achieving their full potential, especially when there are resources available that could help. Women expressed experiencing structural violence by not trusting the doctors, feeling like there is not medical treatment that can help them anyway, and not receiving the resources that they need when they seek medical care. Intersectionality relates to structural violence when considering how multiple social identities can overlap to prevent someone from receiving the resources that they need to achieve optimum health.

Many women in the study endorsed some form of fear around health care providers and getting medical treatment which we also define as structural violence; ranging from feeling judged for experiencing IPV to being afraid of learning about permanent disability from the abuse. These findings expand the qualitative meta-analysis by Feder, Hutson, Ramsay, and Taket (2006) that found that women want nonjudgmental health care providers who respect their decisions around interventions and actions to address the IPV. However, women included in those reviewed studies were women who were already receiving health care and understanding what prevents women from getting health care is an important concept to explore in future studies.

Women in the study were speaking up on behalf of other women who cannot speak for themselves, describing other women they know as “being so damaged their minds are gone” or telling the story of a friend who went to sleep after getting hit in the head and never woke up. They wanted their stories shared so other women would not make the same mistakes or would see warning signs in dangerous relationships early enough to get out before permanent damage or death. This points to the fact that women know there is danger in their lives, but they feel invisible and like no one is talking to them about it.

Women will continue to experience negative outcomes related to lack of TBI screening and diagnosis if more research is not conducted to begin to understand the challenges and structural violence of their complex situations. This study adds an important finding that all women in primary data collection experienced some form of TBI before receiving a TBI from IPV. Future research should focus on understanding how different mechanisms of injury for TBI could lead to different health outcomes and begin to explore TBI as a risk factor for entering into an abusive relationship and not only as an outcome of the IPV.

Expanding Intersectionality

Crenshaw (1991) called for intersectionality that goes beyond race/class/gender to explore intragroup differences. This study explores the way that living with the consequences of TBI influences women’s lives and ability to access resources to end IPV, or the converse, the way they prioritize ending IPV over seeking resources to address their TBIs. The findings fit with the definition of intersectional analysis by rethinking work and family identity (Collins, 2015). These women are experiencing symptoms of probable TBI that interfere with their ability to get and keep a job and if they have a job, they might have to give it up because the abusers exhibit extreme stalking behavior and could find them at work. By invoking isolation as protection, the women are redefining family identity and support (or lack of) from their family and friends. Specific consequences of TBI, such as problems with recall and memory, may be interfering with the legal process of pressing charges or applying for custody, complicating two of the traditional avenues available for protection.

Limitations

To fully embrace the concept of intersectionality, it is important to think of the women who were excluded from the study (Nash, 2008). First, only women who were abused by men and spoke English were included in the study. Second, to participate in the study women needed access to a phone with minutes available to do a 40-minute interview. Third, no women described physical disabilities but women living with disabilities might not be able to access the shelter or be able to accomplish a phone call without assistance, which could have placed them at greater risk for abuse. The women in the study talked about their friends who had died from getting hit in the head and about the women in the shelter who had been hit so many times in the head that “their minds are gone.” They were recognizing women like them who were excluded. The sample was representative of women who were unemployed or underemployed and an important area of future research is exploring how women in a higher social status experience TBI from IPV.

Implications for Health Care Providers

Women in this study described living with symptoms of depression which supports findings from a recent study. Iverson & Pogoda (2015) compared women veterans who self-reported a TBI from IPV (18.8%, classified as TBI from self-report using a modified version of Veterans Affairs (VA) TBI screening tool) to women who did not meet TBI criteria on the screening tool but were still hit in the head during an episode of IPV. Women who screened positive for TBI had significantly higher levels of depression (mean Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score 26.6 vs. 20.7, p < .0001) and PTSD (mean Posttraumatic Disorder Checklist Scores 53.2 vs. 34.1, p < .0001) and significantly lower perceptions of physical health (mean SF-12 scores 34.6 vs. 42.3, p < .01) than women who experienced trauma to the head without screening positive for a TBI using the screening tool. Health care providers working with women who are at high risk for TBI from IPV should ask about depressive symptoms, and women receiving treatment for depression should be asked about a history of TBI and IPV.

It is important to think about ways to break down the silos of resources to create relationships between shelters and health care entities to make it easier for women to access resources for both TBI and IPV. Outpatient concussion clinics could start doing outreach with women’s shelters to build relationships. Service providers, such as women’s shelters and homeless shelters, should consider having low stimulation areas available for all people living with TBIs.

Implication for Future Research

Instead of focusing on immediate, acute treatment for TBI from IPV, future research could focus on lingering symptoms of TBI (which also overlap with PTSD), including symptoms that prevent women from getting and keeping a job (such as decreased cognitive and executive function, problems with sleep, and depression). An important question for future prevention of IPV is whether or not young girls who receive a head injury in adolescence, such as concussion from sports or TBI with hospitalization and rehabilitation, are at increased risk of entering into an abusive relationship.

Future interdisciplinary research should focus on women living with TBI from IPV to improve long-term health; develop and test interventions to address lingering symptoms of TBI; and help health care providers understand how structural violence might impact women’s ability to feel safe while getting care.

Conclusion

This is one of the first studies to explore how structural violence might influence the lives of women with TBI from IPV. The definition of structural violence used in this study opens up new pathways to create structural interventions. Acknowledging an expanded definition of violence may be a necessary first step in creating an expanded definition of safety. Research should move beyond an individual level to look at TBI from IPV at the population level, incorporating structural violence, race, and community level risk factors that might make groups of people more vulnerable to receiving a TBI.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by NIH/NINR Grant R01009093 and HRSA T32HP30036.

Author Biographies

Amanda St. Ivany, is postdoctoral research fellow at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. Her research interests include understanding the experiences of women who are living with brain injuries from intimate partner violence, exploring how having a brain injury could be a risk factor for experiencing or perpetrating violence, and increasing screening and access to neurological rehabilitation services for women living with a brain injuries.

Susan Kools, is the Madge M. Jones professor of Nursing at the University of Virginia and a child and adolescent psychiatric nurse scientist with a program of research centered on health and mental health disparities experienced by adolescents. She is an internationally recognized expert on qualitative methods and known for her pioneering work in dimensional analysis, an approach to generating grounded theory.

Linda Bullock, is professor Emeritus at the University of Virginia School of Nursing. As Co-PI of the DOVE grant, she oversaw the rural study sites.

Phyllis Sharps, is the Elsie M. Lawler Endowed Chair, Professor of Nursing and associate Dean for Community Programs and Initiatives, at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. She is internationally known for her research, leadership of interdisciplinary research teams and her advocacy for violence against pregnant and parenting women. As the PI of the DOVE grant she oversaw all aspects of the study, with specific emphasis on the urban sites.

Donna L. Schminkey, is an assistant professor in the Acute and Specialty Care department, University of Virginia School of Nursing, and a practicing nurse-midwife in Harrisonburg, VA.

Kristin Wells, is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Virginia with expertise in epidemiologic study design and social determinants of health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anderson JC, Stockman JK, Sabri B, Campbell DW, & Campbell JC (2015). Injury outcomes in African American and African Caribbean women: The role of intimate partner violence. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 41(1), 36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M, Basile K, Breiding M, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, … Stevens MR (2011). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2010 summary report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet, 359, 1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AE, Friese C, & Washburn R (2017). Situational analysis grounded theory after the interpretive turn (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J (2009). Taking an analytic journey In Morse JM, Stern PN, Corbin J, Bowers B, Charmaz K, & Clarke AE (Eds.), Developing grounded theory: The second generation (1st ed., pp. 35–53). Walnut Creek, CA.: Left Coast Press [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD, Wolfe M, Mysiw WJ, Jackson RD, & Bogner JA (2003). Early identification of mild traumatic brain injury in female victims of domestic violence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1(Suppl. 5), S71–S76. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw KW (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A (2014). Violence-related mild traumatic brain injury in women: Identifying a triad of postinjury disorders. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 21, 300–308. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer PE, Nizeye B, Stulac S, & Keshavjee S (2006). Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Medicine, 3(10), e449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder GS, Hutson M, Ramsay J, & Taket AR (2006). Women exposed to intimate partner violence: Expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: A meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(1), 22–37. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Wuest J, & Merritt-Gray M (2011). Intimate partner violence and nursing practice In Humphreys J & Campbell J (Eds.), Family violence and nursing practice (pp. 115–153). New York: Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung J (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6, 167–191. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/422690 [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, & Pogoda TK (2015). Traumatic brain injury among women veterans: An invisible wound of intimate partner violence. Medical Care, 53(4 Suppl. 1), S112–119. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly U (2011). Theories of intimate partner violence from blaming the victim to naming the injustice: Intersectionality as an analytic framework. Advances in Nursing Science, 34(3), E29–E51. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182272388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kools S, McCarthy M, Durham R, & Robrecht L (1996). Dimensional analysis: Broadening the conception of grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 6, 312–330. doi: 10.1177/104973239600600302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Glass N, Campbell J, Melvin KC, Barr T, & Gill JM (2011). Traumatic brain injury in intimate partner violence: A critical review of outcomes and mechanisms. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12, 115–126. doi: 10.1177/1524838011404251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash JC (2008). Re-thinking intersectionality. Feminist Review, 89(1), 1–15. doi: 10.1057/fr.2008.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pawluch D, & Neiterman E (2010). What is grounded theory and where does it come from? In De Vries R, Bourgeault I, & Dingwall R (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative methods in health research. pp. 174–192. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rich K (2014). “My body came between us”: Accounts of partner-abused women with physical disabilities. Affilia, 29, 418–493. doi: 10.1177/0886109914522626 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff RM, Iverson GL, Barth JT, Bush SS, Broshek DK, & NAN Policy and Planning Committee. (2009). Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: A national academy of neuropsychology education paper. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 24, 3–10. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Ivany A, & Schminkey D (2016). Intimate partner violence and traumatic brain injury: State of the science and next steps. Family & Community Health, 39, 129–137. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharps P, Alhusen JL, Bullock L, Bhandari S, Ghazarian S, Udo IE, & Campbell J (2013). Engaging and retaining abused women in perinatal home visitation programs. Pediatrics, 132(Suppl. 2), S134–S139. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1021L [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin J (1990). Basics of qualitative research (Vol. 15). Newbury Park: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Zieman G, Bridwell A, & Cardenas JF (2017). Traumatic brain injury in domestic violence victims: A retrospective study at the barrow neurological institute. Journal of Neurotrauma, 34, 876–880. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]