Abstract

Despite the known benefits of breastmilk, associations between breastfeeding and child overall health outcomes remain unclear. We aimed to understand associations between breastfeeding and health outcomes, including child weight, through age 3. Analysis included women (N=3,006) in the longitudinal, prospective First Baby Study from 2009 to 2014. For this analysis, breastfeeding initiation and duration were measured using self-reported data from the 1-, 6- and 12-month surveys; child illnesses were analyzed from the 6-, 12-, and 24-month interviews; height and weight at age 3 were used to determine overweight/obese (≥85th percentile) and obese (≥95th percentile). Adjusted logistic regressions were utilized to determine significance. Greater duration of breastfeeding was associated with fewer reported acute illnesses at 6 months (p<0.001) and fewer diarrheal illness/constipation episodes at 6, 12, and 24 months (p=0.05) in adjusted analyses. Fewer breastfed children, compared to non-breastfed children, were overweight/obese (23.5% vs. 37.8%; p=0.032) or obese (9.1% vs. 21.6%; p=0.012) at age 3. Breastfeeding duration was negatively associated with overweight/obese (never breastfed: 37.8%, 0–6 months: 26.9%, >6 months: 20.2%; p=0.020) and obesity (never breastfed: 21.6%, 06 months: 11.0%, >6 months: 7.3%; p=0.012). Overall, our findings support the hypothesis that duration of breastfeeding is associated with fewer reported acute illnesses at 6-months of age and diarrheal illness and/or constipation episodes at 6-,12- and 24-months. Additionally, results from our study suggest a protective effect of breastfeeding from childhood overweight/obesity, as children who received breastmilk for 6 months or longer had lower odds of overweight/obesity at age 3 years.

Keywords: childhood obesity, breastfeeding, body mass index

Introduction

Breastfeeding rates in the U.S. have steadily increased over the past decade, but remain well below the WHO Global Nutrition Targets for 2015 which established an exclusive breastfeeding target rate of 50% up to 6 months of age.1 The 2016 National Immunization Survey indicated that only 21.9% of mothers were exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum and 29.2% were breastfeeding at 1 year. 2 The short-and long-term benefits of breastfeeding on infant health is well evidenced and includes reduced incidence of childhood illnesses, acute otitis media, severe lower respiratory tract infections, asthma, constipation, gastrointestinal infection, and eczema.3–7

Although extensive research supports the medical benefits of breastfeeding, research examining the relationship between breastfeeding and infant weight has generated conflicting results.8 Over the past three decades, childhood obesity rates in America have tripled, and today, nearly one in three children in America is overweight or obese.9 Worldwide obesity has more than doubled since 1980 and in 2014, 41 million children under the age of 5 were overweight or obese.9 As a result of this epidemic, research on the prevention of childhood obesity, including breastfeeding research, has elicited much scientific interest.10 Differences in overweight/obesity risk in breastfed versus non-breastfed infants are likely influenced by differences in maternal sociodemographic factors such as race and education, as well as maternal health (e.g., overweight/obesity) which is seldom reported or controlled for in published studies.11 Furthermore, information on duration of breastfeeding is not always reported, thus the optimal duration of breastfeeding necessary to reduce the likelihood of a child being overweight/obese remains unknown.12

The primary aim of this secondary data analysis from the First Baby Study (FBS) was to investigate potential associations between the initiation and duration of breastfeeding on parent-reported childhood illnesses and child weight. We hypothesized that children who were breastfed for the recommended 6 months or longer, would have fewer parent reported illnesses at 6-, 12-, and 24 months of age and a lower likelihood of overweight/obesity at 3 years.

Methods

Study Design

FBS was a longitudinal prospective study that involved prenatal and postnatal interviews with mothers through child age 3 years. The primary outcome of the FBS was to investigate the effect of mode of first delivery (vaginal vs. cesarean section) on subsequent childbearing outcomes.13 Participant interviews occurred during pregnancy, between 30 and 42 weeks gestation, and included questions assessing sociodemographic factors. The 1-month postpartum telephone interview focused on the events of labor and delivery. Follow-up telephone interviews were conducted at 6-, 12-, 18-, 24-, 30-, and 36-months postpartum. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Penn State College of Medicine as well as at participating hospitals throughout Pennsylvania. Additional details about the study design are previously published.13

Participants

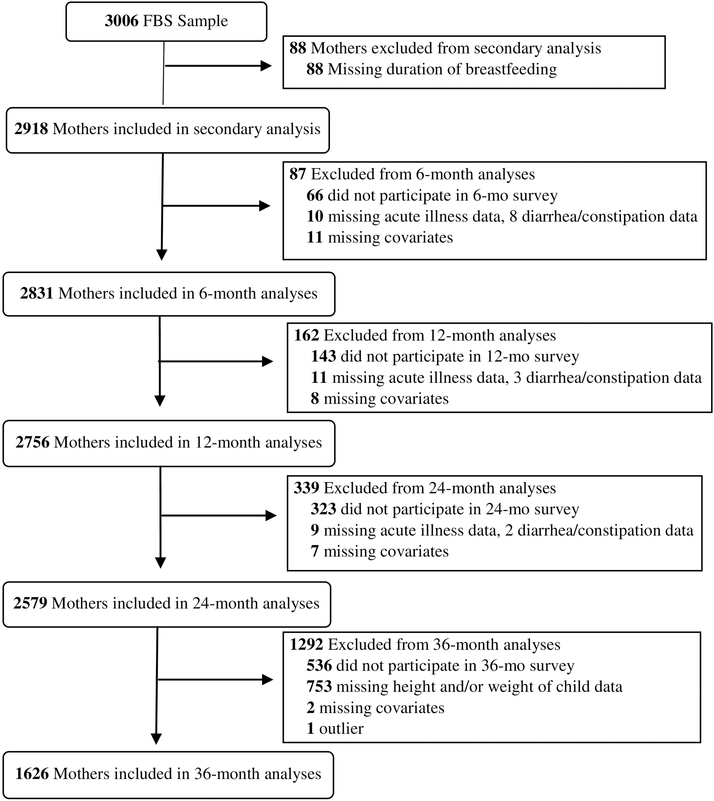

Recruitment of study participants occurred from January 2009 through April 2011. Participants were recruited via clinic and community-based methods (e.g., study brochures displayed in offices, clinics, community health centers and mailed to potentially eligible women by a Medicaid insurer; internet postings; childbirth classes, hospital tours). Trained study recruiters determined eligibility in-person or by telephone. The final sample size of women who completed both the baseline and 1-month postpartum interview was 3006. The flow chart of study participation at each data collection stage can be seen in Figure 1. Eighty-eight women were missing data on breastfeeding duration and were excluded from this secondary analysis, resulting in a sample size of 2918 women. Figure 1 provides details of sources of missing data at the 6-, 12-, 24- and 36-months data collection stages. There were 2423 women who participated in the 36 month survey, for a retention rate of 80%. Although the mothers were sent detailed instructions as to how to measure the height and weight of their first child prior to the 36 month survey, only 1653 reported both height and weight at the 36 months survey. Among the sample of 2918 mother-child pairs available for this secondary analysis, 1629 reported the height and weight of the child, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram of Secondary Analysis

Study Variables

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding initiation and duration were obtained by maternal self-report at 1-, 6- and 12-months postpartum. Because the FBS did not distinguish the dyadic behavior in which infants obtain breast milk, “breastfeeding” was defined as an infant receiving breast milk, regardless of exclusivity (added formula or solid foods) or method of feeding (breast or bottle). For breastfeeding initiation, mothers were asked at the 1-month interview, “Have you ever breastfed or tried to breastfeed your baby?”. If they responded “no” they were coded as “never breastfed” (n = 251). Additionally, one woman had missing data at the 1-month interview but reported at the 6 month interview that she had never breastfed or tried to breastfeed, so she was also categorized as “never breastfed”, for a total of n = 252. Breastfeeding duration categories included “never breastfed”, “breastfed 0–6 months”, and “breastfed >6 months”, derived from maternal responses at 1-, 6- and 12-months interviews as to the length of time they reported breastfeeding.

Reported Child Illnesses

Child illnesses were reported every 6 months, from 1 month to 36 months of age, with mothers reporting whether or not their child had experienced the following illnesses in the past 4 weeks: cough or cold; respiratory infection (respiratory flu, asthma, bronchiolitis, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); ear infection; fever of ≥100.4°F for ≥24 hours; constipation; diarrhea; diaper rash; allergic reaction to new food; eczema; and/or asthma.13 For this analysis, cough/cold, respiratory infection, ear infection and fever were combined and termed “acute illnesses”. If the mother reported that her child experienced one or more of these four conditions in the previous four weeks we categorized the child as having had an acute illness. Constipation and diarrhea were combined and termed “diarrheal illness/constipation”. If the mother reported that her child experienced one or both of these conditions in the previous four weeks the child was categorized as having had diarrheal illness/constipation.

Body mass index

Children’s height and weight were measured and reported by mothers at the 36 month postpartum interview.13 Body mass index (BMI) values were calculated and the 2000 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Growth charts were used to categorize three sets of weight variables: underweight/healthy weight (<85th percentile), overweight/obese (≥85th percentile), and obese (≥95th percentile). 14

Confounding Variables

Potential confounding variables included maternal age (i.e., categorized as 18–24, 25–29, 30–36 years), race (white vs. non-white), education (high school degree or less, some college, college degree or higher), relationship status (married, living with partner, not partnered or not living with partner), smoking in pregnancy (yes, no), gestational weight gain (GWG) exceeding guidelines (yes, no), pre-pregnancy BMI category (normal and underweight, overweight, or obese) and gestational age (late preterm, early term, or term and post-term). With the exception of gestational age (obtained from birth certificate records), confounding variables were self-reported during the baseline telephone interview. Further, birth certificate data was also used in cases where data were missing or implausible. Confounding variables were carefully chosen to reflect variables that have been suggested in previous literature to affect breastfeeding and child health outcomes including childhood illnesses and obesity.3,15 Using IOM recommendations for GWG, women were categorized as exceeding or not exceeding the recommended GWG for their respective pre-pregnancy BMI categories.16 Gestational age at the time of delivery (in weeks) and pre-pregnancy BMI were included as continuous variables.

Statistical analysis

The study variables were summarized with frequencies and percentages or with means, medians, and standard deviations prior to any analysis. All analyses were performed using statistical software SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The associations between “ever breastfed” and demographic variables were tested using the Chi-square test. A logistic regression model was used to analyze the association of duration of breastfeeding with acute or gastrointestinal illness at each time point. Logistic regression was also used to test for associations between “ever breastfed” or breastfeeding duration with BMI percentile ≥ 85 (overweight/obese) and BMI percentile ≥95 (obese). Odds ratios were used to quantify the magnitude and direction of any significant associations. Models including potential confounding variables and covariates were applied to determine if significant associations with duration of breastfeeding were maintained when adjusted for these other variables. To measure the effect of attrition we compared those who dropped out of the study to those who were retained on key variables, including breastfeeding initiation. In addition we conducted sensitivity analyses (via multiple imputation of missing data) to investigate the effect of attrition on the study outcomes.

Results

As shown in Table 1, 91.4% of the First Baby Study participants reported breastfeeding at least once at the 1-month postpartum interview. Breastfeeding was higher in women who were older (30–36), white, educated (college degree or higher), married, and non-smokers. Additionally, mothers with a pre-pregnancy BMI <30 (normal or overweight) were more likely to breastfeed than mothers with a pre-pregnancy BMI ≥30 (obese).

Table 1.

Characteristics of First Baby Study participants by breastfed vs. never breastfed (N = 2918)

| Variable | Total | Breastfed (n=2666; 91.4%) | Never Breastfed (n=252; 8.6%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | <0.001 | |||

| 18–24 | 777 (26.6) | 652 (83.9) | 125 (16.1) | |

| 25–29 | 1161 (39.8) | 1085 (93.5) | 76 (6.5) | |

| 30–36 | 980 (33.6) | 929 (94.8) | 51 (5.2) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.003 | |||

| White | 2438 (83.6) | 2244 (92.0) | 194 (8.0) | |

| Non-White | 479 (16.4) | 421 (87.9) | 58 (12.1) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| High School Degree or Less | 481 (16.5) | 381 (79.2) | 100 (20.8) | |

| Some College | 776 (26.6) | 690 (88.9) | 86 (11.1) | |

| College Degree or Higher | 1661 (56.9) | 1595 (96.0) | 66 (4.0) | |

| Marital Status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 2061 (70.6) | 1952 (94.7) | 109 (5.3) | |

| Not Married | 857 (29.4) | 714 (83.3) | 143 (16.7) | |

| Smoked During Pregnancy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 306 (10.5) | 243 (79.4) | 63 (20.6) | |

| No | 2612 (89.5) | 2423 (90.9) | 189 (7.2) | |

| Gestational Weight Gain (GWG) | 0.590 | |||

| Exceeded Recommended GWG | 1577 (54.2) | 1445 (91.6) | 132 (8.4) | |

| Did Not Exceed Recommended GWG | 1332 (45.8) | 1213 (91.1) | 119 (8.9) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI category (kg/m2) | <0.001 | |||

| Normal and underweight (<25.0) | 1661 (57.0) | 1546 (93.1) | 115 (6.9) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 646 (22.2) | 589 (91.2) | 57 (8.8) | |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 609 (20.9) | 529 (86.9) | 80 (13.1) | |

| Gestational age | 0.171 | |||

| Late preterm (< 37 wks, 0 dys) | 116 (4.0) | 110 (94.8) | 6 (5.2) | |

| Early term (37 wks, 0 dys to 38 wks, 6 dys | 561 (19.2) | 504 (89.8) | 57 (10.2) | |

| Term and post-term (39 wks, 0 or older) | 2241 (76.8) | 2052 (91.6) | 189 (8.4) | |

Pennsylvania, 2009–2014

Note. Missing data: race/ethnicity = 1; pre-pregnancy BMI n = 5; gestational weight gain n = 9

Values are absolute numbers (percentages).

Reported Illnesses

After adjusting for all covariates, breastfeeding initiation showed minimal protective effects on reported illnesses as compared to breastfeeding duration. No significant differences were seen at 6-, 12- or 24 months in the “never breastfed” vs. “ever breastfed” comparisons. Duration of breastfeeding was associated with fewer reported acute illnesses at 6-months (p < 0.001), but not at 12 months or 24 months (Table 2). Breastfeeding duration was also negatively associated with reported diarrheal illness/constipation episodes, with fewer diarrheal illnesses/constipation episodes at 6 months (p = 0.014), 12 months (p = 0.012), and 24 months of age (p = 0.030).

Table 2.

Reported illnesses at 6-, 12- and 24-months of age by breastfeeding duration

| Acute Illnesses | OR (95% CI) | Diarrheal Illness/Constipation | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months | Yes (n=1445) | No (n= 1386) | Yes (n=871) | No (n=1964) | ||

| Never Breastfed | 135 (57.2) | 101 (42.8) | Reference | 87 (36.6) | 151 (63.4) | Reference |

| 0–6 Months | 775 (54.2) | 656 (45.8) | 0.90 (0.64, 1.27) | 472 (32.9) | 962 (67.1) | 0.89 (0.63, 1.27) |

| >6 Months | 535 (46.0) | 629 (54.0) | 0.66 (0.46, 0.96) | 312 (26.8) | 851 (73.2) | 0.70 (0.48, 1.02) |

| 12 Months | Yes (n=1424) | No (n= 1332) | Yes (n=964) | No (n=1800) | ||

| Never Breastfed | 123 (56.2) | 96 (43.8) | Reference | 90 (40.9) | 130 (59.1) | Reference |

| 0–6 Months | 722 (52.7) | 647 (47.3) | 0.83 (0.58, 1.19) | 524 (38.1) | 850 (61.9) | 0.96 (0.67, 1.38) |

| >6 Months | 579 (49.6) | 589 (50.4) | 0.71 (0.49, 1.04) | 350 (29.9) | 820 (70.1) | 0.74 (0.51, 1.09) |

| 24 Months | Yes (n=1373) | No (n=1206) | Yes (n=822) | No (n=1764) | ||

| Never Breastfed | 101 (53.2) | 89 (46.8) | Reference | 60 (31.1) | 133 (68.9) | Reference |

| 0–6 Months | 685 (54.4) | 574 (45.6) | 0.98 (0.67, 1.44) | 439 (34.8) | 824 (65.2) | 1.24 (0.83, 1.85) |

| >6 Months | 587 (52.0) | 543 (48.1) | 0.85 (0.58, 1.27) | 323 (28.6) | 807 (71.4) | 0.98 (0.64, 1.49) |

Pennsylvania, 2009–2014

Values are absolute numbers (percentages). Odds ratios are adjusted for model covariates.

Child Body mass index

Overall, there were significant associations between breastfeeding and child BMI percentiles for the breastfeeding initiation (p < 0.05) and duration (p < 0.05) comparisons. After adjustment for potential confounding variables and covariates, analyses demonstrated breastfeeding was negatively associated with child BMI, with a significantly smaller proportion of overweight/obese and obese children at age 3 among those that were “ever breastfed”. Also, a lower percentage of children were found to be overweight/obese if breastfed compared to those “never breastfed” (23.5% vs. 37.8%; p = 0.032). Children who received breastmilk had lower odds (95% CI: 0.41–0.96) of being overweight/obese, compared to those who were never breastfed. A lower percentage of children were obese in the breastfed group than the never breastfed group (9.1% vs. 21.6%; p = 0.012). Children who were “ever breastfed” had lower odds (95% CI: 0.30–0.86) of reported obesity, compared to children who were never breastfed. Children with a longer duration of breastfeeding had lower rates of overweight/obese (never breastfed: 37.8%, 0–6 months: 26.9%, >6 months: 20.2%; p = 0.020) and obesity (never breastfed: 21.6%, 0–6 months: 11.0%, >6 months: 7.3%; p = 0.012).

Sensitivity Analyses

Although 2423 (80%) of the study participants were retained to the 36 month interview, only 1653 (55.0% of the original 3006 study participants) reported their child’s height and weight at the 36 month survey. Comparing those who dropped out to those who stayed in the study, we found that there were demographic differences between the women who completed the study and the women lost to follow-up: those who were lost to follow-up were significantly younger, more likely to be non-white, less educated, less likely to be married or partnered and more likely to have smoked during pregnancy. In addition, only 69.4% of the women who never breastfed completed the study, while 90.4% of the women who breastfed for more than 6 months did (p < 0.001). However, sensitivity analyses using multiple imputation of missing data indicated that the results of the regression models were nearly identical to the results excluding the missing data.

Discussion

The aim of this analysis was to examine associations between breastfeeding and child health utilizing a large cohort of first-born children from Pennsylvania. Overall, our findings support the hypothesis that initiation and duration of breastfeeding are associated with fewer reported acute illnesses at 6-months of age and diarrheal illness and/or constipation episodes at 6- and 12-months. Children who received breastmilk for longer than 6 months also had lower odds of overweight/obesity or obesity at age 3 years.

Our findings (Table 1) were consistent with previous research which demonstrates that breastfeeding rates are associated with maternal sociodemographic characteristics including race/ethnicity, level of education and age.1 Breastfeeding was higher in our participants who were older (30–36), white, educated (college degree or higher), married, non-smokers and non-obese women.1 Our study adds to the body of breastfeeding literature by including confounding variables not controlled for in other studies (i.e. pre-pregnancy BMI and GWG).11,16

Consistent with previous research,4 this study demonstrated a similar duration-response relationship between breastfeeding and reported illnesses within the first 6 months of life. Specifically, we found evidence that supports the protective effects of breastmilk on both reported acute illnesses and diarrheal illnesses and/or constipation episodes at 6 months of age.4 However, in contrast to prior work,4 our study did not reveal continued protective effects of breastfeeding on reported acute illnesses beyond 6 months of age.

Results from our study also suggest a protective effect of breastfeeding against childhood overweight/obese and obesity, adding to the extensive, yet inconclusive, literature in this area. A 2013 systematic review of breastfeeding literature that included three separate meta-analyses concluded that breastfed infants were at a reduced risk of childhood obesity. 11,17–19 However, in contrast to our analysis, several of the studies included in the review failed to adjust for known confounders associated with breastfeeding and childhood health outcomes such as maternal BMI and GWG.11

While this study substantiates current literature describing the protective effects of breastfeeding, some published research purports that breastfed infants are just as likely to be overweight or obese as non-breastfed children.20–21 Uwawzuoke, Eneh, and Ndu10 suggested that a positive relationship between breastfeeding and healthy childhood weight outcomes only highlighted the exclusion of possible confounders, in their 2017 review article. These authors concluded that breastfeeding was not related to pediatric obesity, but rather the observed protective effects may be a result of sociodemographic confounders, such as maternal obesity and maternal smoking.10 While there is some indication that studies that controlled for confounding variables, such as maternal socioeconomic factors and gestational age, reported smaller benefits of breastfeeding,22 our current analysis diverges from this trend by demonstrating a significant relationship between breastfeeding and its effect on child weight by adjusting for under-controlled variables.

Our study has several unique strengths. The FBS is a large, observational study, which allows for determination of associations limited by smaller studies. Further, the study design allowed reported illnesses and breastfeeding data to be obtained every 6 months, thereby limiting participant recall bias. Additionally, a recent review showed that maternal report of breastfeeding is reliable through the age of 3 year.23 The longitudinal nature of this study permitted us to assess reported health outcomes up to age 3. In addition, we controlled for several important confounding variables, including maternal age, GWG, pre-pregnancy BMI, and smoking.

This study does, however, have several limitations. The primary limitation of this secondary analysis is that observational studies cannot fully account for differences in sociodemographic factors, physiology, and behaviors between participants.12 Although this analysis attempted to statistically adjust for measures associated with breastfeeding and child health outcomes, unique differences among participants likely remain and may affect our findings.24 In addition, FBS participants were more likely to be white, college educated, married and to have private insurance than women aged 18–36 delivering their first child in the State of Pennsylvania.13 Selection bias may have occurred as a result of these participation rates, as well as demographic differences between the women who completed the study and the women lost to follow-up (significantly younger, more likely to be non-white, less educated, less likely to be married or partnered and more likely to have smoked during pregnancy). Impacting the generalizability of the study is the potential bias of attrition which is one of the major methodological problems associated with longitudinal studies.25

It is also important to consider that this study did not differentiate between exclusive versus non-exclusive breastfeeding. The inclusion of formula fed infants may potentially dilute the true effect of breast milk and bias results toward the null hypothesis.3 Further, the interpretation of these data is confounded by the lack of definition of whether breastmilk in our analysis was given by breast or by bottle. Previous observational studies showed infants who were fed by bottle, formula, or expressed breastmilk have poorer self-regulation and excessive weight gain in late infancy compared with infants nursed only from the breast.26–27

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insight into the relationship between breastfeeding and child health outcomes. In general, there was less reported overweight/obese and obese children at age 3 within the breastfed group. The findings of this study have potential economic and societal impact in that most overweight/obese children remain overweight/obese as adults, thus increasing morbidity, mortality and national healthcare expenditures.28 Our study supports previous reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) that suggest strategies to increase the number of mothers who breastfeed for the recommended 6 months would be of great economic benefit on a national level.29 This is particularly true for children exposed to a high number of maternal biopsychosocial risk factors for obesity, including increased maternal BMI, low maternal education and smoking during pregnancy.30 While prior studies recommend exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months, this study supports the benefits of continued breastfeeding on child weight outcomes through the first year, in accordance with AAP guidelines.26 Given that breastfeeding is a highly accessible and low-cost preventative public health measure that can help reduce the odds of childhood reported illnesses and obesity, efforts to promote continued breastfeeding throughout a child’s first year of life are a worthwhile endeavor. Future studies should examine subsets of women who are less likely to breastfeed (ex. mothers with higher BMIs, mothers who exceed GWG recommendations) and further determine preventative measures to support successful breastfeeding in these target populations.

Table 3.

Overweight/obese and obesity reported at child age 36 months by breastfeeding initiation and duration (N =1626).

| Overweight/Obese (≥85 percentile) | OR (95% CI) | Obese (≥95 percentile) | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 398) | No (n = 1228) | Yes (n=162) | No (n=1464) | |||

| Breastfeeding Initiation | ||||||

| Never Breastfed | 42 (37.8) | 69 (62.2) | Reference | 24 (21.6) | 87 (78.4) | Reference |

| Breastfed | 356 (23.5) | 1159 (76.5) | 0.63 (0.41, 0.96) | 138 (9.1) | 1377 (90.9) | 0.51 (0.30, 0.86) |

| Breastfeeding Duration | ||||||

| Never Breastfed | 42 (37.8) | 69 (62.2) | Reference | 24 (21.6) | 87 (78.4) | Reference |

| 0–6 Months | 203 (26.9) | 553 (73.1) | 0.68 (0.44, 1.05) | 83 (11.0) | 673 (89.0) | 0.54 (0.32, 0.94) |

| >6 Months | 153 (20.2) | 606 (79.8) | 0.54 (0.34, 0.85) | 55 (7.3) | 704 (97.7) | 0.43 (0.24, 0.78) |

Pennsylvania, 2009–2014

Values are absolute numbers (percentages). Odds ratios are adjusted for model covariates.

Highlights.

Breastfeeding duration associated with fewer reported acute illnesses at 6-months

Breastfeeding duration negatively associated with diarrheal illness/constipation

Analyses demonstrated breastfeeding negatively associated with child BMI

Longer breastfeeding duration resulted in lower rates of overweight/obesity

Acknowledgement:

The First Baby Study was supported by [grant number R01HD052990] the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, NIH. The project is also funded, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco CURE funds. The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses interpretations or conclusions.

Funding Acknowledgement: The First Baby Study was supported by [grant number R01HD052990] the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, NIH. The project is also funded, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco CURE funds. The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses interpretations or conclusions.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding among U.S. children born 2002–2013, CDC National Immunization Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/index.htm Accessed June 9, 2016, Updated August 1, 2017.

- 2.World Health Organization. WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Breastfeeding Policy Brief. 2014. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/globaltargets_breastfeeding_policybrief.pdf

- 3.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, et al. Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. In. Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duijts L, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Moll HA. Prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of infectious diseases in infancy. Pediatrics 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowatte G, Tham R, Allen K, Lau M, Dai X, Lodge C. Breastfeeding and childhood acute otitis media: a systematic review of meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica 2015;104:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turco R, Miele E, Russo M, Mastroianni R, Lavorgna A, Paludetto R, et al. Early-life factors associated with pediatric functional constipation. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition 2014;58(3):307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silvers KM, Frampton CM, Wickens K, Pattemore PK, Ingham TI, Fishwick D, et al. Breastfeeding protects against current asthma up to 6 years of age. The Journal of Pediatrics 2012;160:991–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brion MJ, Lawlor D, et al. What are the causal effects of breastfeeding on IQ, obesity, and blood pressure? Evidence from comparing high-income with middle-income cohorts. International Journal of Epidemiology 2011;40:670–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogden CL, Carrol MD, Kit BK, & Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA; 2014, 311, 806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uwawzuoke SN, Eneh CI, & Ndu IK. Relationship between exclusive breastfeeding and lower risk of childhood obesity: A narrative review of published evidence. Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics 2017; 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lefebre CM, & John RM. The effect of breastfeeding on childhood overweight and obesity: A systematic review of the literature. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014. July;26(7):386–401. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12036. Epub 2013 Jul 12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oken E Fields DA. Lovelady CA, & Redman LM. TOS scientific position statement: Breastfeeding and obesity. Obesity: A Research Journal 2017; 25(11):1864–1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kjerulff K, Velott D, Zhu J, al e. Mode of first delivery and women’s intentions for subsequent childbearing: Findings from the First Baby Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013;27:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuczmarski R, Ogden C, Guo S, al e. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. In. National Center for Health Statistics: Vital Health Stat; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo L, Liu J, Ye R, Liu J, Zhuang Z, & Ren A (2015). Gestational Weight Gain and Overweight in Children Aged 3–6 Years. Journal of Epidemiology, 25(8), 536–543. 10.2188/jea.JE20140149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IOM, NRC. Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arenz S, Ruckerl R, Koletzko B, von Kries R. Breast-feeding and childhood obesity—a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1247–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harder T, Bergmann R, Kallischnigg G, Plagemann A. Duration of breastfeeding and risk of overweight: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG. Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: a quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1367–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jing H1, Xu H, Wan J, Yang Y, Ding H, Chen M, Li L, Lv P, Hu J, Yang J. Effect of breastfeeding on childhood BMI and obesity: the China Family Panel Studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(10):e55. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Redsell SA, Edmonds B, Swift JA, Siriwardena AN, Weng S, Nathan D, and Glazebrook C Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions that aim to reduce the risk, either directly or indirectly, of overweight and obesity in infancy and early childhood. 2016; Matern Child Nutr, 12: 24–38. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horta BL, Victora CG. Long-Term Effects of Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li R, Scanton K, Serdula M. The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. In: Nutri Rev; 2005. p. 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarlenski MP, Bennett WL, Bleich SN, Barry CL, Stuart EA. Effects of breastfeeding on postpartum weight loss among U.S. women. Prev Med 2014; 69:146–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustavson K, von Soest T, Karevold E, & Røysamb E (2012). Attrition and generalizability in longitudinal studies: findings from a 15-year population-based study and a Monte Carlo simulation study. BMC Public Health, 12, 918 10.1186/1471-2458-12-918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R1, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Association of breastfeeding intensity and bottle-emptying behaviors at early infancy with infants’ risk for excess weight at late infancy. Pediatrics. 2008. October;122 Suppl 2:S77–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li R, Fein SB, et al. Do infants fed from bottles lack self-regulation of milk intake compared with directly breastfed infants? Pediatrics 2010;125(6):e1386–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabin MA, Kiess W. Childhood Obesity: Current and Novel Approaches. Best Practice and Research Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2015;29:327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. In: Pediatrics AAo, editor.: PEDIATRICS; 2012. p. e827–e841.22371471 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carling SJ, Demment MM, Kjolhede CL, Olson CM. Breastfeeding duration and weight gain trajectory in infancy. Pediatrics 2015; 135(1):111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]