Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to compare the accuracy of a smartphone application and a mechanical pedometer for step counting at different walking speeds and mobile phone locations in a laboratory context.

Methods

Seventeen adults wore an iPphone6© with Runtastic Pedometer© application (RUN), at 3 different locations (belt, arm, jacket) and a pedometer (YAM) at the waist. They were asked to walk on an instrumented treadmill (reference) at various speeds (2, 4 and 6 km/h).

Results

RUN was more accurate than YAM at 2 km/h (p < 0.05) and at 4 km/h (p = 0.03). At 6 km/h the two devices were equally accurate. The precision of YAM increased with speed (p < 0.05), while for RUN, the results were not significant but showed a trend (p = 0.051). Surprisingly, YAM underestimates the number of step by 60.5% at 2 km/h. The best accurate step counting (0.7% mean error) was observed when RUN is attached to the arm and at the highest speed.

Conclusions

RUN pedometer application could be recommended mainly for walking sessions even for low walking speed. Moreover, our results confirm that the smartphone should be strapped close to the body to discriminate steps from noise by the accelerometers (particularly at low speed).

Keywords: Measurement, Pedometry, Physical activity, Public health

Introduction

It is well documented that a prolonged decrease of physical activity results in the rise of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes,1 obesity,2 hypertension,3 coronary diseases4 and therefore increases the healthcare costs.5 Considering that 44% of the European population does not exercise6 and that the WHO recommendations of 150 min of moderate physical activity per week are only fulfilled by 30% of the Swiss population,7,8 it is a priority for public health policies to encourage individuals to be more active.9

Being physically active by walking is free of charge, presents limited risks of injury and can be practiced in many places by those who can walk. That's the reason why Public health institutions are developing walking-based programs to encourage people to increase their level of physical activity.10,11 These programs are supported by large amounts of studies showing that walking 30 min/day, 5 days/week diminishes risks of cardiovascular accident by 19%11 and also has a positive impact on psychological well-being and diminishes the risks of depression.12,13 Ideally, it is recommended for adults between 26 and 65 years to reach at least 7000 steps per day.14 In an educational perspective, pedometers are often used in health promotion as they are easy to use, low-cost, motivational and self-monitoring tools for sedentary persons.15 In addition, a recent study showed that using a pedometer is likely to be a more precise way to assess the level of physical activity as compared with subjective measure, especially in sedentary sub-population.16 Pedometer-based programs are considered to be efficient to increase the volume of physical activity. In their systematic review, Bravata and collaborators10 showed that when the use of a pedometer is associated with daily step goal, walking performance can be increased by an average of 2187 steps/day. Interestingly, an extra 2000 steps/day in men with very low physical activity (i.e. 2000 steps/day) has been associated with reduced waist circumference17 supporting the assumption that increase of steps in sedentary population is likely to have major impact on health outcomes. The Yamax Digiwalker products range of pedometers (Yamasa Tokei Keiki Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) are usually used as reference devices because they showed the best accuracy scores and reliability for step counting.18,19 However, it is also generally reported that at lower speed the error rate increases.20 The work of Basset and colleagues (1996) already revealed that between walking speeds of 50 m/min and 70 m/min, the accuracy was less than 80% steps counted. Considering that preferred walking speed can be very low in general population,21 the accuracy of these devices at very low speeds (i.e. at 2 km/h) in real world setting may be lower.

The aim of this study is twofold: to evaluate the effect of different speeds on the accuracy of one pedometer application but also to test this accuracy when the smartphone is attached at different locations. First, the increased number of pedometer applications and the rapid evolution of technology allow smartphones to be used as step counters 22 Second, few studies have been conducted to validate the accuracy of Smartphone pedometer applications so far, while the location of the device seems to influence the accuracy of the step counts.23,24 Two studies have found applications to be inaccurate.25,26 In two other studies, the results are less straightforward. Åkerberg and colleagues found one application (Pedometer 24/7©) out of ten to be accurate27 and Leong and Wong found one (Pedometer Tayutau©) application out of three to be accurate.20 In this study, we tested the Runtastic Pedometer© application, which was one of the most popular pedometer application.28 Because of its popularity among the Swiss population, the Iphone6© was selected among the multiple mobile phone models (Iphone6 is the best-selling mobile phone in Switzerland with 56% of the Swiss customers that possess this model at the time of the study versus 39% for its direct concurrent Android).29 In addition, Åkerberg and collaborators concluded that the Iphone4© model was accurate with reasonable low standard deviation.27 Probably, because it is equipped with a BMA280 accelerometer discriminating accelerations between 1/512 g and 1/4906 g, whereas walking from 2 to 8 km/h induces 0.1–0.61 g accelerations at hip level.30

Our hypotheses were that 1) the smartphone application would be as accurate as the pedometer; 2) the sensibility of the smartphone accelerometers would be more accurate than the mechanical lever of the pedometer at slow speeds; and 3) the accuracy of the smartphone accelerometers would disrupt the measures in the loosest position (“jacket”).

Methods

Participants

The sample size was calculated based on the Japanese standards for pedometer error that should not exceed 3%.19 The walking duration for the current study was 4 min and 50 s, which correspond to approximatively 500 steps.31 A sample size of 17 participants was deemed sufficient to detect a delta of 15 steps (with alpha = 0.05; power = 90%; standard deviation = 13 steps). We increased this number to 18 participants in case of drop-out.

The 18 participants (7 women, 11 men) involved in the study were aged between 30 and 60 years old. Participants with walking difficulties, chronic diseases, acute diseases, prosthesis and/or electronic medical devices were not included in the study. One subject was removed because of extreme outlier values at five different positions and back-pains after performing the task. The other outliers were excluded as individual data points and represent a total of 2.8% of the entire data set. Those outlier values were due to a technical malfunction of the Yamax Digiwalker. A total of 17 subjects (11 men, 6 women, age: 40 ± 10 yr) were considered for the statistical analysis of the data. The experimental protocol (n°31/15) was approved by the local ethic committee of the Canton de Vaud and was in agreement with the declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave their written informed consent before participating to the experiment. They received 15 Swiss Francs for their participation.

Experimental design

During the protocol, the participant wore comfortable clothes and sport shoes. They were equipped with an iPhone 6© (Apple, United-States) on which the Runtastic Pedometer© (Runtastic, Austria) (RUN) application was installed. The sensitivity was set to “moderate”, in line with the results of Boyce and collaborators26 that pointed out good validity and reliability for two out of three mobile phone pedometers when set at the medium level of sensitivity. They were also equipped with a Yamax Digiwalker SW200© (Yamax, Japan) pedometer (YAM). The walking tests were performed on an instrumented Treadmill T150-FMT-MED© (Arsalis, Belgium), which measured the ground reaction forces in the vertical, forward and lateral axes at a sampling rate of 100 Hz, and it was used as reference during this study (see Dierick et collaborators for validation32) (see below for details).

The experiment took place at the University of Lausanne, in the laboratory of the Institute of Sport Sciences. After having the opportunity to acquaint themselves with the treadmill during several minutes, the participant was then equipped with the pedometer and the smartphone. The pedometer was worn on a belt, over the middle of the right thigh, as described in its instruction manual. The smartphone was inserted in a phone case and worn at three different positions: « belt », the smartphone is attached to the belt, in vertical position; « arm », the smartphone is attached around the arm, over the biceps, in vertical position; and « jacket », the smartphone is attached to the jacket, in horizontal position. Two sizes (Small and Large) of the same model of jacket were used according to the anthropometry of the participants. The participants were asked to walk during 4 min and 50 s at three incremental walking speeds: 2, 4 and 6 km/h (respectively 0.56, 1.11 and 1.67 m/s; zero gradient). For security reasons, the speeds were not randomized to avoid to start at the highest one. At each speed, the walking task was repeated three times in a randomized order with respect to mobile's position (i.e. « belt », « arm » and « jacket »). The number of steps was the primary outcome measured by the application, the pedometer and the treadmill. A custom MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) script was used to extract the step counts from the lateral axis peak force of each foot contact on the treadmill.

Data analysis

The quantitative variable used in the statistical analysis was named DIFFSTEP. It was calculated as the difference between the numbers of steps counted by one of the tested devices (YAM or RUN) and the number of steps measured by the treadmill. DIFFSTEP was calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

The closer DIFFSTEP is to zero, the more accurate the device is. Note that for YAM DIFFSTEP correspond to the mean score of the steps recorded at the three positions of the mobile phone.

The absolute percent error (APE) was also calculated33 as follows:

| (2) |

Statistical analysis

Because the DIFFSTEP measure was not normally distributed and did not show homoscedasticity, non-parametrical statistic tests were used. Wilcoxon rank signed tests were performed to compare the two devices at different speeds and Friedman tests to compare the different speeds for each device. To compare the effect of the positions, Friedman tests were used on the data for RUN only. Bland Altman plots and Spearman's correlations were computed to further describe the data. Bland Altman plots were used to determine congruency between each device and reference 34. They display the variability in individual step counts around 0, the mean error score and the 95% confidence interval. Scores close to 0 indicate congruency between the two devices. Positive scores (over 0) indicate overestimation of device relative to treadmill, and negative scores (under 0) indicate underestimation. The significant threshold was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Table 1 summarizes the data for DIFFSTEP and APE scores. The average number of steps made by all participants on all conditions were 353.2 ± 48 at 2 km/h, 494.2 ± 28.5 at 4 km/h and 577.2 ± 26.7 at 6 km/h.

Table 1.

Mean ± standard error of the mean for DIFFSTEP and absolute percentage error (APE) according to the two devices (YAM and RUN), the three walking speeds and the three locations of the mobile phone.

| Location | Speed | Device | DIFFSTEPa Mean ± SEM | APEb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean score YAMc | 2 km/h | YAM | −195 ± 26.7 | 60.5 |

| 4 km/h | YAM | −20 ± 6.8 | 12.5 | |

| 6 km/h | YAM | −4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.4 | |

| Belt | 2 km/h | RUN | 59.3 ± 24.7 | 19.3 |

| 4 km/h | RUN | −2.2 ± 3.1 | 1.5 | |

| 6 km/h | RUN | −1.3 ± 1.4 | 0.7 | |

| Arm | 2 km/h | RUN | 1.3 ± 23.2 | 19.7 |

| 4 km/h | RUN | 0.8 ± 1.9 | 1.1 | |

| 6 km/h | RUN | −2.2 ± 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| Jacket | 2 km/h | RUN | 79.9 ± 21.3 | 24.1 |

| 4 km/h | RUN | 20.6 ± 8.8 | 4.3 | |

| 6 km/h | RUN | −3.8 ± 1.0 | 0.7 |

Positive scores indicate an overestimation of steps and negative scores indicate an underestimation.

In bold the mean values that do not exceed the 3% validity threshold determined by the Japanese industry.19

The global mean score of number of steps measured by YAM at the three positions of the mobile phone.

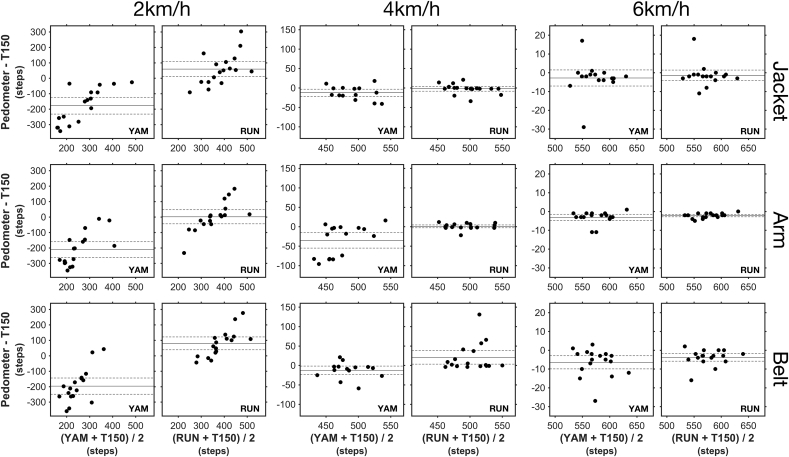

At 2 km/h, the average DIFFSTEP were −195 ± 26.7 for YAM and 59.3 ± 24.7 for RUN (at “belt” position). Bland Altman graphs at 2 km/h display the underestimation of YAM and overestimation of RUN for the three conditions (Fig. 1). Dispersion and large confidence intervals also revealed the high inter-individual variability of the measures at slow speeds. At 4 km/h, the average DIFFSTEP for YAM was −20 ± 6.8, whereas it was −2.2 ± 3.1 for RUN (at “belt” position). Bland Altman analysis at 4 km/h showed an underestimation of YAM for all conditions (Fig. 1). The dispersion was lower than at 2 km/h.

Fig. 1.

Bland Altman plots for the two devices (YAM and RUN) compared to the reference (treadmill T150) at 2, 4 and 6 km/h at each location. Solid line is mean error (of steps); dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals.

At 6 km/h, the average DIFFSTEP for YAM was −4.1 ± 0.7 whereas it was −1.3 ± 1.4 for RUN (at “belt” position). In the Bland Altman graphs, we can observe that both devices were accurate and homogeneous (very low inter-individual dispersions) in the three conditions (Fig. 1).

Concerning the APE, at 2 km/h, the 3% validity threshold was not reached for YAM (60.5%) and for RUN in « belt» (19.3%), « arm » (19.7%) and « jacket » (24.1%) positions. At 4 km/h, the only conditions reaching the validity threshold were RUN « arm » (1.1%) and RUN « belt » (1.5%) positions. At 6 km/h, YAM was above the validity threshold (4.4%, average of all positions), whereas all RUN positions were below the validity threshold.

Rank tests analyses

When the DIFFSTEPS measures were compared at the “belt” position, the analyses showed a significant statistical difference between YAM and RUN at 2 km/h (p < 0.001) but not at 4 km/h (p = 0.38) and 6 km/h (p = 0.18). The Friedman tests showed a significant statistical difference between the speeds for YAM (p < 0.001). DIFFSTEP decreased significantly between 2 km/h and 6 km/h. Regarding RUN, there was no significant difference for the speeds at the “arm” (p = 0.25) and “belt” (p = 0.051) positions. However, a significant speed effect at the “jacket” position (p < 0.001) was found, showing a significant increase of error at the slowest (2 km/h) compared to the highest speed (6 km/h).

Concerning the comparison of the RUN data in the three positions, we observed statistical differences between the three different positions at 2 km/h (p = 0.019) and at 4 km/h (p = 0.049), but not at 6 km/h (p = 0.45) for DIFFSTEP. At 2 km/h and 4 km/h, DIFFSTEP was greater in the “jacket” position compared to the two other positions (Table 1).

Spearman correlations

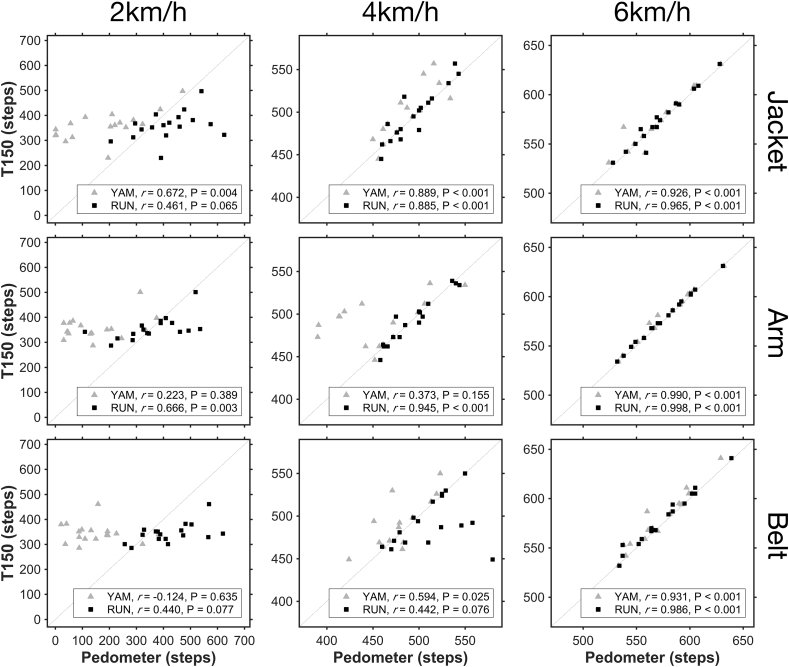

The Spearman correlations confirmed the effect of speed on the accuracy of both devices (Fig. 2). Indeed, we can observe that correlations between the two devices and the reference (T150) increased with speed. In addition, RUN clearly indicated higher coefficients of correlation when strapped on the arm at the three speeds (from 0.66 to 0.99) as compared to the two other locations.

Fig. 2.

Spearman correlations between the two devices (YAM and RUN) compared to the reference (treadmill T150) at each speed (2, 4 and 6 km/h) and for each location. Solid line represents the line of identity.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to compare the Runtastic Pedometer© smartphone application and the Yamax Digiwalker SW-200© with the data acquired by a treadmill (used as reference for the step counting). According to our results, the accuracy of the smartphone application is better than the mechanical pedometer at 2 km/h and 4 km/h. At 6 km/h, the two devices show a similar accuracy.

There was a statistical difference between the two devices at 4 km/h where RUN had a 1.5% error rate and YAM a 12.5% error rate. Only the smartphone application reached the 3% error validity threshold at 4 km/h. At 6 km/h, there was no statistical difference between the two devices even if RUN was well below the 3% error validity threshold (<0.7%) and YAM was slightly above this threshold (4.4%). However, at 2 km/h the differences between both devices were significant. The average error percentage for YAM at 2 km/h (all data) was 60.5%. This result is consistent with another study using the Yamax Digiwalker SW-200©,35 where authors attribute this error percentage to the sensibility threshold of the device. The Yamax Digiwalker SW-200© is indeed designed to be used at greater speeds, at which the forces generated by the hips (≥0.35 g) are sufficient to trigger the step count.35,36 The average error percentage of RUN at 2 km/h was 34.4% making this device still more accurate than YAM at slow speeds. This might be due to the fact that the iPhone6© accelerometers are more sensitive than the mechanical lever of the YAM. This sensitivity is good at slow speeds in controlled settings, although it could be a problem in more variable opened environmental conditions. For example, it is still not well documented whether the Runtastic Pedometer© can distinguish between steps and movement of the phone in the pocket when it is not properly strapped as in our settings; or whether it can count steps if the user answers the phone or texts a message (non-ambulatory activities). In addition, car travel can lead to additional steps if the sensitivity settings are high.26 Such questions should be addressed in other research, as it would be important to investigate deeper how the device works in free-living conditions.

For RUN, the “jacket” position was the least accurate of the three positions which confirms the conclusion of Åkerberg et al. (2012). This is probably due to the “looseness” of this position, which makes it difficult for the sensitive accelerometers of the iPhone6© to discriminate steps from noise. Consequently, it would be recommended to wear the smartphone as close as possible to the body, and strapped as tightly as possible. By comparing various newer pedometers that can be placed anywhere on the body, Park and collaborators37 found a reduction of accuracy for some of them when they were place in the pocket or in a purse. The hypothesis of the “looseness” of a position being a problem is also supported by the results of a study using an Omron HJ203© pedometer (Omron, Switzerland). In that study, the most precise position was found to be around the neck, close to the body.23 Furthermore, two studies indicate that positions “pocket” and “in backpack” are not accurate.24 For the “pocket” position, the authors hypothesize that the movement of the thigh cannot be well detected. In our study, the “arm” position was the most precise by far. Even if RUN was more precise than YAM at 2 km/h, it cannot be considered as trustworthy because its error percentage is exceeding the 3% validity threshold. We should note here that the inaccuracy of both devices at slow speeds is troublesome for an everyday use. A study has indeed shown that lean and obese individuals use to walk at very slow speeds during daily life.21

Nevertheless, a step counter can be used in a clearly defined period of walking, in a semi-controlled context. For example, someone who wants to go five times a week to walk 3000 steps/day, which corresponds to the recommendations of the WHO, could use the step counter with a higher degree of precision. In this context, the smartphone would be used only for step-counting and could be fixed in one of the three described positions and would therefore be more precise than the YAM. Ideal positions could be suggested, like the “arm” position of our study, in which RUN was the most precise. In that case, for a 3000-steps walk (about 30 min), the device would add only 33 additional steps at 4 km/h as compare to the YAM that would add 375 steps. It is thus important to recommend to keep the same device during the walking-based program. It is noteworthy to mention that some studies showed slight kinematics changes in gait parameters when treadmill versus overground walking are compared.38 Even if we do not expect a major impact on steps counting, further researches in more ecological conditions are needed. The overall conclusion that RUN is more accurate than YAM in a laboratory context is a relevant finding, which allows to recommend Runtastic Pedometer© for step counting especially when it is use for delimited session of physical activities.

Conclusion

Globally, the results showed that the Runtastic Pedometer© application was a more accurate step counter in controlled settings than the Yamax Digiwalker SW200©. In addition, it was more accurate when strapped on the arm. Our findings have shown the limits of the Yamax Digiwalker SW200©, which is nowadays widely used by public health organisms. The accuracy of a smartphone application over a standard pedometer opens up new possibilities for research, for example in post-surgery rehabilitation or health promotion for older adults or clinical populations, since these settings involve similar low speed conditions as used in this study. It also opens up possibilities for health promotion because smartphone are everyday used objects. Consequently, it makes studies focused on the everyday use of smartphones as step counters extremely interesting. Smartphone pedometer applications and connected bracelets are developing very fast and it seems crucial in the fields of sports sciences and health promotion to consider the new technologies as a complementary tool to help populations to reach physical activity recommendations.

Declarations of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants for their commitment and would like to thank the "Ligues de la santé du Canton de Vaud" for the financial support. They also wish to express their gratitude to Cathia Rossano for her helpful assistance during the experiments.

Contributor Information

Bastien Presset, Email: Bastien.Presset@unil.ch.

Balazs Laurenczy, Email: balazs.laurenczy@id.ethz.ch.

Davide Malatesta, Email: Davide.Malatesta@unil.ch.

Jérôme Barral, Email: jerome.barral@unil.ch.

References

- 1.Lee I.-M., Shiroma E.J., Lobelo F., Puska P., Blair S.N., Katzmarzyk P.T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack G.R., Virk J.S. Driving towards obesity: a systematized literature review on the association between motor vehicle travel time and distance and weight status in adults. Prev Med. 2014;66:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health, Physical activity, Health improvement and Prevention . Department of Health, Physical activity, Health improvement and Prevention; London, UK: 2004. At Least Five a Week, Evidence of the Impact of Physical Activity and its Relationship to Health, a Report from the Chief Medical Officer. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein R.A., Rockman C.B., Guo Y. Association between physical activity and peripheral artery disease and carotid artery stenosis in a self-referred population of 3 million adults. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. October 2014 doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider H., Venetz W., Gallani Berardo C. Bundesamt für Gesundheit; Bern, Switzerland: 2009. Overweight and Obesity in Switzerland, Part 1: Cost burden of Adult Obesity in 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Commission . Sport and Physical Activity Report. European Commission; Brussels: 2014. Directorate-general for education and culture, & TNS opinion & social.http://bookshop.europa.eu/uri?target=EUB: NOTICE:NC0214406:EN: HTML [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosclaude M., Ziltener J.-L. Les bienfaits de l’activité physique (et/ou les méfaits de la sédentarité). Bern. Rev Med Suisse. 2010;6:1495–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organisation Mondiale de la Santé . Organisation Mondiale de la Santé; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. Recommandations mondiales sur l’activité physique pour la santé. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office fédéral de la santé publique OFSP . OFSP; Bern, Switzerland: 2010. Quelle est notre alimentation et notre activité physique? Tendances en matière d’alimentation et d’activité physique. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bravata D.M., Smith-Spangler C., Sundaram V. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298(19):2296. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murtagh E.M., Murphy M.H., Boone-Heinonen J. Walking: the first steps in cardiovascular disease prevention. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;22(5):490–496. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32833ce972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guglani R., Shenoy S., Sandhu J. Effect of progressive pedometer based walking intervention on quality of life and general well being among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s40200-014-0110-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hörder H., Skoog I., Frändin K. Health-related quality of life in relation to walking habits and fitness: a population-based study of 75-year-olds. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(6):1213–1223. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tudor-Locke C., Craig C.L., Brown W.J. How many steps/day are enough? For adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2011;8:79. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassett D.R., Wyatt H.R., Thompson H., Peters J.C., Hill J.O. Pedometer-measured physical activity and health behaviors in United States adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(10):1819–1825. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181dc2e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sitthipornvorakul E., Janwantanakul P., van der Beek A.J. Correlation between pedometer and the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire on physical activity measurement in office workers. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):280. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwyer T., Hosmer D., Hosmer T. The inverse relationship between number of steps per day and obesity in a population-based sample – the AusDiab study. Int J Obes. 2006;31(5):797–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassett D.R., Ainsworth B.E., Leggett S.R. Accuracy of five electronic pedometers for measuring distance walked. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28(8):1071–1077. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199608000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crouter S.E., Schneider P.L., Karabulut M., Bassett D.R. Validity of 10 electronic pedometers for measuring steps, distance, and energy cost. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1455–1460. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078932.61440.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leong J.Y., Wong J.E. Accuracy of three Android-based pedometer applications in laboratory and free-living settings. J Sports Sci. March 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1154592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine J.A., McCrady S.K., Lanningham-Foster L.M., Kane P.H., Foster R.C., Manohar C.U. The role of free-living daily walking in human weight gain and obesity. Diabetes. 2008;57(3):548–554. doi: 10.2337/db07-0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klasnja P., Pratt W. Healthcare in the pocket: mapping the space of mobile-phone health interventions. J Biomed Inf. 2012;45(1):184–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Cocker K.A., De Meyer J., De Bourdeaudhuij I.M., Cardon G.M. Non-traditional wearing positions of pedometers: validity and reliability of the Omron HJ-203-ED pedometer under controlled and free-living conditions. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15(5):418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu W., Lee M. Invariance of wearing location of Omron-BI pedometers: a validation study. J Phys Activ Health. 2010;7(6):706–717. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.6.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergman R.J., Spellman J.W., Hall M.E., Bergman S.M. Is there a valid app for that? Validity of a free pedometer iPhone application. J Phys Activ Health. 2012;9(5):670–676. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyce G., Padmasekara G., Blum M. Accuracy of mobile phone pedometer technology. J Mob Technol Med. June 2012:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Åkerberg A., Lindén M., Folke M. How accurate are pedometer cell phone applications? Procedia Technol. 2012;5:787–792. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comparisch Classement des Smartphones: les 10 favoris des Suisses. 2014. https://fr.comparis.ch/telecom/mobile/news/2014/04/Smartphone-verkauf-rangliste-schweiz.aspx

- 29.Comparisch Marché Suisse du Smartphone 2014, le boom en bref. 2014. https://fr.comparis.ch/telecom/mobile/news/2014/02/Smartphone-markt-2014-iphone-android.aspx

- 30.Satkunskiene D., Grigas V., Eidukynas V., Domeika A. Acceleration based evaluation of the human walking and running parameters. J Vibroengineering. 2009;11(3):506–510. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tudor-Locke C., Craig C.L., Brown W.J. How many steps/day are enough? for adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2011;8:79. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dierick F., Penta M., Renaut D., Detrembleur C. A force measuring treadmill in clinical gait analysis. Gait Posture. 2004;20(3):299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Masurier G.C., Lee S.M., Tudor-Locke C. Motion sensor accuracy under controlled and free-living conditions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(5):905–910. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000126777.50188.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bland J.M., Altman D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet Lond Engl. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cyarto E.V., Myers A.M., Tudor-Locke C. Pedometer accuracy in nursing home and community-dwelling older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(2):205–209. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000113476.62469.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Masurier G.C., Tudor-Locke C. Comparison of pedometer and accelerometer accuracy under controlled conditions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(5):867–871. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000064996.63632.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park W., Lee V.J., Ku B., Tanaka H. Effect of walking speed and placement position interactions in determining the accuracy of various newer pedometers. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2014;12(1):31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alton F., Baldey L., Caplan S., Morrissey M.C. A kinematic comparison of overground and treadmill walking. Clin Biomech. 1998;13(6):434–440. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(98)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]