Abstract

Background

Excessive stress causes varied physiological and psychological disorders including male reproductive problems. Here, we attempted to investigate the protective effects of Korean Red Ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer; KRG) against sub-acute immobilization stress-induced testicular damage in experimental rats.

Methods

Male rats (age, 4 wk; weight, 60–70 g) were divided into four groups (n = 8 in each group): normal control group, immobilization control group, immobilization group treated with 100 mg/kg of KRG daily, and immobilization group treated with 200 mg/kg of KRG daily. Normal control and immobilization control groups received vehicle only. KRG (100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg) was mixed in the standard diet powder and fed daily for 6 mo. Parameters such as organ weight, blood chemistry, sperm kinematic values, and expression levels of testicular-related molecules were measured using commercially available kits, Western blotting, and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Data revealed that KRG restored the altered testis and epididymis weight in immobilization stress-induced rats significantly (p < 0.05). Further, KRG ameliorated the altered blood chemistry and sperm kinematic values when compared with the immobilization control group and attenuated the altered expression levels of spermatogenesis-related proteins (nectin-2, cAMP responsive element binding protein 1, and inhibin-⍺), sex hormone receptors (androgen receptor, luteinizing hormone receptor, and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor), and antioxidant-related enzymes (glutathione S-transferase m5, peroxiredoxin-4, and glutathione peroxidase 4) significantly in the testes of immobilization stress-induced rats.

Conclusion

KRG protected immobilization stress-induced testicular damage and fertility factors in rats, thereby indicating its potential in the treatment of stress-related male sterility.

Keywords: androgen, glutathione, immobilization stress, inhibin, Korean Red Ginseng

1. Introduction

The cause of impaired semen quality in the majority of affected men is unknown. The most framed risk factors of male infertility are environmental pollution, occupational chemicals, smoking, chemotherapy, aging, and stress. These risk factors are related to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, thereby damaging the sperm quality and resulting in infertility [1]. Stress is a major contributing factor to numerous diseases, such as cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative disorders. Several studies have attempted to analyze the association between semen quality and stress derived from varied sources like occupation, life events, and infertility [2], [3], [4]. Excessive emotional stress in developing countries, accompanied by rapid industrialization, may also severely affect male infertility.

In men, physical and psychological stress could interfere with the reproductive capability. Various stressors induce activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and subsequent suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis might be one of the major mechanisms underlying the male reproductive system dysfunction [5]. Experimental animals subjected to chronic restraint or immobilization stress are believed to be a valid and reliable model for mimicking human psychological stress. Several antioxidants were investigated for their antistress activities using the chronic restraint or immobilization-induced stress model [6], [7], [8]. Korean Red Ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer; KRG) from the family Araliaceae is an important, multifunctional medicinal herb that has long been used to treat various diseases [9], [10], [11]. The major active ginsenoside components present in KRG possess varied physiological activities, namely anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects and deliver beneficial effects in the treatment of various disorders linked to the central nervous system, cardiovascular, reproductive, and immune systems [12], [13], [14]. Ginseng showed promising effects on senile and dioxin-induced testicular dysfunction largely due to its profound antioxidant capacity [15], [16].

In a previous study, our group reported that KRG improved the antioxidant enzyme status during aging, thereby ameliorating the occurrence of age-related disorders associated with free radicals and oxidative stress [15], [17]. Additionally, we observed that KRG reversed testicular dysfunction in aged rats [14]. In the present study, the effects of KRG on body weight, organ weight, blood chemistry, and sperm kinematics were evaluated in rats with immobilization-induced stress. Furthermore, changes in the key antioxidant enzymes, spermatogenesis-related factors, and sex hormone receptors in the testicular tissue of stress-induced rats were analyzed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of KRG water extract

The 6-yr-old P. ginseng root extract was supplied by the Korea Ginseng Corporation (Daejeon, Korea). The extraction procedure was followed as described in our previous reports [18]. In brief, the roots were washed with tap water, steamed at 98°C for 60 min, and dried at 70°C for 72 h to obtain KRG. The active constituents were obtained by extracting KRG with 10 volumes of water at 90°C for 48 h, followed by filtration. The filtrate was dried under reduced pressure to obtain a thick, ginsenoside-rich, dark-brown water extract (KRG-WE).

2.2. Analysis of ginsenosides by ultra-performance liquid chromatography

The sample preparation was performed as described in a previous report [19]. Briefly, 2 g of KRG-WE weighed in a beaker was added with 15 mL of deionized water and left for 1 h at room temperature. The sample was transferred in to a volumetric flask and was brought up to 50 mL with methanol. Extraction was performed using an ultra-sonication technique (60 hz, Wiseclean) for 45 min. The resulting solution was filtered (0.2μM, Acrodisk, Port Washington, NY, USA) and subjected to ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) analysis.

For UPLC analysis, a Waters ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters, Millford, MA, USA) composed of a binary solvent manager, sample manager, and photo diode array detector was used. The separation was accomplished on an ACQUITY BEH C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters) at a column temperature of 40°C. The binary gradient elution system consisted of 0.001% phosphoric acid in water (A) and 0.001% phosphoric acid in acetonitrile (B). The separation was achieved using the following gradient program: 0–0.5 min (15% B), 14.5 min (30% B), 15.5 min (32% B), 18.5 min (38% B), 24.0 min (43% B), 27.0 min (55% B), 27.0–31.0 min (55% B), 35.0 min (70% B), 38.0 min (90% B), 38.1 min (15% B), and 38.1–43.0 min (15% B). The flow rate was set at 0.6 mL/min, and the sample injection volume was 2.0 μL. The 30 ginsenosides were detected by photo diode array detector at 203 nm.

2.3. Experimental animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (age, 4 wk; weight, 60–70 g) were purchased from Orient Bio Co. (Seong Nam, Korea) and allowed to acclimatize at the Regional Innovation Center Experimental Animal Facility, Konkuk University, at least 1 wk prior to the experiment. Rats were housed in individual cages at a constant temperature (23 ± 2°C) and relative humidity (55 ± 5%) on a 12-h light/dark cycle. Food consumption was measured daily, and body weight was recorded weekly. For generating a physical-emotional stress model, sub-chronic intermittent immobilization stress was applied. The rats were immobilized in a rat holder (Jeung Do Bio & Plant Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) for 2 h/day for 8 weeks. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines (Permission No: KU15197) as per the 14th article of Korean Animal Protection Law.

2.4. Experimental design

The rats were divided into four groups: normal control group (NC; n = 8), immobilization control group (IC; n = 8), immobilization group treated with 100 mg/kg body weight of KRG daily (IK100; n = 8), immobilization group treated with 200 mg/kg body weight of KRG daily (IK200; n = 8). NC and IC groups received vehicle only. KRG (100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg) was administered for 6 mo. The dose of KRG-WE was based on our previous experiments [14], [15]. For the non-stressful administration of KRG, it was mixed in the standard diet powder and orally administered as a pellet. Daily dietary intake and weekly body weight were monitored for adjustment of the appropriate amount of KRG intake. After 6 mo, animals were fasted for 24 h and sacrificed under general anesthesia with carbon dioxide. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture, and serum was separated by centrifugation for serum markers and enzyme analysis. Testes and epididymis were excised, washed in ice-cold saline, and the adhering fat and connective tissues were removed. A 10% homogenate of the tissue was prepared in Tris-HCl buffer (0.1M; pH 7.4), centrifuged (2500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C) to pellet the cell debris, and the supernatant was harvested for biochemical assays.

2.5. Sperm kinematics

For kinematic analysis, live sperms were extracted from the left caudal epididymis. After dissecting the epididymis with scissors, one drop of the caudal fluid was immediately dropped in a culture plate filled with 5 mL of Hanks' balanced salt solution pre-warmed to 37°C and containing 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin. The sperm motility was recorded using a computer-assisted sperm analyzer (Hamilton Thorne Inc., Beverly, MA, USA) as described previously [16]. More than 200 sperms per sample were monitored for the motility pattern analysis.

2.6. Determination of serum markers

To measure biochemical parameters and complete blood counts, blood was collected in a serum-separating tube gel and clot activator tube (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Serum was separated by centrifugation (1,500 g, 10 min at room temperature). An automated chemistry analyzer (Hitachi-747; Hitachi Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure the serum levels of triglyceride (TG), glucose (GLU), total protein (T-PRO), albumin (ALB), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). A part of the blood was collected in a test tube containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Vacutainer K3E, BD Biosciences, Plymouth, UK) to measure the blood cell count using an automated blood cell analyzer (Sysmex NE-8000, TOA Medical Electronics, Kobe, Japan).

2.7. RNA isolation and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

For evaluating the mRNA expression level of spermatogenesis-related molecules, sex hormone receptors, and antioxidant enzymes, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed. Total RNA was extracted from the testis tissue using the RNA-Bee reagent (AMS Bio, Abingdon, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed as previously described [16]. An aliquot (200 ng) of the reverse transcription products was amplified in a 25-mL reaction volume using a GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega Co., Madison, WI, USA) in the presence of 10pM oligonucleotide primer [17]. The primers used are shown in Table 1. PCR was performed for 30 cycles at 95°C for 40 s, 56°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 40 s. The obtained PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, and the bands were visualized by fluorescence. The intensity of the bands was analyzed using the Image J software package version 1.41o (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in this experiment

| Group | Parameter | Direction | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spermatogenesis-related biomarker molecules | Nectin-2 | Forward | 5′-AGT GAC CTG GCT CAG AGT CA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TAGGTACCAGTTGTC ATC AT-3′ | ||

| CREB-1 | Forward | 5′-ACT GGC TGC TTT GTG TTC AG-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TAC TAG CTT GGG GAG GGG TG-3′ | ||

| Inhibin-α | Forward | 5′-AGG AAG GCC TCT TCA CTT ATG TAT T-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CTC TTG GAA GGA GAT ATT GAG AGC-3′ | ||

| Sex hormone | AR | Forward | 5′-CTG GAC TAC CTG GAT CTC TA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCT GGG CTG TAGTTT TAT TG-3′ | ||

| LHR | Forward | 5′-CTA TCT CCC TGT CAA AGT AA-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TTT GTA CTT CTT CAA ATC CA-3′ | ||

| FSHR | Forward | 5′-GGA CTG AGT TTT GAA AGT GT-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TTC CAT AAC TGG GTT CAT CA-3′ | ||

| Antioxidant enzymes | GPx4 | Forward | 5′-GCA AAA CCG ACG TAA ACT ACA CT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CGT TCT TAT CAA TGA GAA ACT TGG T-3′ | ||

| GSTm5 | Forward | 5′-TAT GCT CCT GGA GTT TAC TGA TAC C-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-AGA CGT CAT AAG TGA GAA AAT CCA C-3′ | ||

| PRx4 | Forward | 5′-CTG ACT GAC TAT CGT GGG AAA TAC T-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-GAT CTG GGA TTA TTG TTT CAC TAC C-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-AAC TTT GGC ATT GTG GAA GGG C-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-ACA CAT TGG GGG TAG GAA CAC G-3′ | ||

AR, androgen receptor; CREB-1, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) responsive element binding protein; FSHR, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; LHR, luteinizing hormone receptor.

2.8. Western blot analysis

The protocol for Western blotting was followed according to our previous reports [14]. The obtained protein expressions were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and a chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK).

2.9. Statistical analyses

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's t test using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of KRG-WE on body, testes, and epididymis weight in rats

As shown in Fig. 1A, the body weight of immobilization stress-induced rats (IC, IK100, and IK200) decreased compared with that of NC rats during the experiment (p < 0.05). However, no significant difference was observed among the groups. The final body weight at 8 wk for NC, IC, IK100, and IK200 groups was 470.2 ± 41.5 g, 387.60 ± 48.3 g, 370.13 ± 38.2 g, and 402.18 ± 39.2 g, respectively. All the animals survived, and no abnormal behavior was observed. The testes weight was significantly lower in the IC group than in the NC group (p < 0.05). However, the IK100 and IK200 groups regained the testes weight compared with the IC group and showed no difference from that of the NC group (Fig. 1B). The epididymis weight also significantly decreased in the IC group compared with that in the NC group (p < 0.05). The epididymis weight of rats in the IK100 group showed no difference from that of the NC group; however, the epididymis weight significantly increased in the IK200 group (p < 0.05) compared with that in the IC group and recovered to normal values as in the NC group (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Effects of KRG on body weight, testis weight, and epididymis weight of immobilization-induced stress in rats. (A) The overall body weight of NC, IC, and IK groups from weeks 1–24 are shown. (B) Effects of KRG on testis weight of immobilization stress-induced rats. (C) Effects of KRG on rat epididymis weight of immobilization stress-induced rats. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (n = 8). Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's t test using the SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). #p < 0.05 compared with the NC group and *p < 0.05 compared with the IC group. IC, immobilization-stressed control; IK100, immobilization-stressed and received 100 mg/kg body weight of KRG; IK200, immobilization-stressed and received 200 mg/kg body weight of KRG; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng; NC, normal control; SEM, standard error of the mean.

3.2. Effects of KRG on sperm kinematics in immobilization stress-induced rats

The effects of KRG on sperm kinematic values are presented in Table 2. The IC group showed significantly decreased motility, progressiveness, and a higher rate of sperm head elongation compared with the NC group. However, the IK100 and IK200 groups showed significant (p < 0.05) improvement in motility and progressiveness compared with the IC group. Only high-dose KRG (200 mg/kg) has improved head elongation. There was no difference in the other sperm kinematic values (average path velocity, straight line velocity, curvilinear velocity, straightness, and linearity) among the four groups.

Table 2.

Effect of KRG on sperm kinematic values in the serum of immobilization stress-induced rats. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (n = 8). Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance, followed by Duncan’s t test using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). #p < 0.05 compared with the NC group and *p < 0.05 compared with the IC group

| Group | Average |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motile (%) | Progressive (%) | VAP (mm/s) | VSL (mm/s) | VCL (mm/s) | STR (%) | LIN (%) | Elongation (%) | |

| NC | 82.67 ± 14.83 | 25.00 ± 12.34 | 30.59 ± 5.74 | 21.77 ± 4.86 | 73.86 ± 9.53 | 70.43 ± 2.51 | 38.00 ± 2.52 | 96.43 ± 2.15 |

| IC | 51.00 ± 8.00# | 17.71 ± 4.79# | 33.21 ± 8.49 | 25.80 ± 8.92 | 81.31 ± 20.09 | 76.86 ± 12.82 | 44.86 ± 14.84 | 99.00 ± 2.65# |

| IK100 | 84.43 ± 13.45∗ | 31.00 ± 9.11∗ | 33.67 ± 3.13 | 23.74 ± 3.18 | 81.37 ± 8.99 | 67.29 ± 5.71 | 35.57 ± 5.26 | 98.00 ± 1.91 |

| IK200 | 93.14 ± 5.27∗ | 36.00 ± 6.73∗ | 33.90 ± 3.66 | 23.99 ± 2.49 | 75.24 ± 6.93 | 69.00 ± 2.65 | 38.29 ± 3.25 | 94.71 ± 1.60∗ |

IC, immobilization-stressed control; IK100, immobilization-stressed + KRG-WE 100 mg/kg body weight/d; IK200, immobilization-stressed + KRG-WE 200 mg/kg body weight/d; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng; KRG-WE: Korean Red Ginseng water extract; LIN, linearity; NC, normal control; SEM, standard error of the mean; STR, straightness; VAP, average path velocity; VCL, curvilinear velocity; VSL, straight line velocity.

3.3. Effects of KRG on blood chemistry and biochemical parameters of immobilization stress-induced rats

Table 3 represents the blood chemistry data for each group. Data revealed a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in white blood cell count in the IC group compared with that in the NC group, and the count in both IK100 and IK200 groups recovered (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the red blood cell count and other parameters, such as hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet, and lymphocyte among the four groups. Lipid metabolism-related serum parameters were analyzed to evaluate the effects of KRG-WE in immobilization stress-induced rats (Table 4). Data showed that GLU, HDL-C, T-PRO, ALB, and BUN were not significantly different among the groups. However, compared with the NC group, the IC group showed a significant decrease in TG and LDL-C levels, whereas the IK200 group showed significantly increased levels of TG compared with the IC group (p < 0.05). Compared with IC group, IK100 did not show any influence on TG and LDL-C levels, and IK200 group did not exhibit a pronounced effect on the LDL-C levels.

Table 3.

Effect of KRG on blood chemistry panels of immobilization-induced stress. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (n = 8). Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance, followed by Duncan’s t test using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). #p < 0.05 compared with the NC group and *p < 0.05 compared with the IC group

| Group | WBC ( × 103/μL) | LYM (%) | RBC ( × 106/μL) | HGB (g/dL) | HCT (%) | PLT ( × 103/μL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 9.21 ± 2.60 | 77.67 ± 5.35 | 8.29 ± 0.31 | 17.51 ± 0.20 | 45.24 ± 1.15 | 944.33 ± 170.61 |

| IC | 6.15 ± 1.27# | 81.04 ± 3.16 | 7.99 ± 0.48 | 17.01 ± 1.34 | 44.16 ± 4.17 | 852.17 ± 164.22 |

| IK100 | 7.59 ± 1.66∗ | 81.44 ± 7.17 | 8.22 ± 0.34 | 16.97 ± 0.60 | 45.09 ± 1.28 | 939.67 ± 304.66 |

| IK200 | 8.74 ± 2.59∗ | 80.59 ± 3.29 | 8.55 ± 0.38∗ | 17.86 ± 0.86 | 46.00 ± 2.18 | 881.40 ± 74.60 |

HCT, hematocrit; HGB, hemoglobin; IC, immobilization-stressed control; IK 100, immobilization-stressed + KRG-WE 100 mg/kg body weight/d; IK 200, immobilization-stressed + KRG-WE 200 mg/kg body weight/d; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng; KRG-WE, Korean Red Ginseng water extract; LYM, lymphocyte; NC, normal control; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; SEM, standard error of the mean; WBC, white blood cell.

Table 4.

Effect of KRG on lipid metabolism-related serum parameters of immobilization-induced stress. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (n = 8). Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance, followed by Duncan’s t test using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). #p < 0.05 compared with the NC group and *p < 0.05 compared with the IC group

| Group | Serum biochemical parameters |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLU (mg/dL) | T-CHOL (mg/dL) | TG (mg/dL) | HDL-C (mg/dL) | LDL-C (mg/dL) | T-PRO (mg/dL) | ALB (g/dL) | BUN (mg/dL) | |

| NC | 165.40 ± 9.66 | 93.6 ± 20.93 | 66.80 ± 15.80 | 21.00 ± 1.58 | 11.00 ± 0.71 | 6.44 ± 0.13 | 2.74 ± 0.05 | 19.56 ± 0.96 |

| IC | 163.80 ± 18.50 | 65.00 ± 26.89 | 45.00 ± 15.98# | 19.00 ± 1.41 | 8.60 ± 2.07# | 6.28 ± 0.18 | 2.72 ± 0.08 | 21.36 ± 2.00 |

| IK100 | 163.40 ± 10.24 | 70.33 ± 16.81 | 46.00 ± 10.37 | 19.40 ± 2.19 | 8.80 ± 1.10 | 6.34 ± 0.21 | 2.72 ± 0.08 | 21.74 ± 2.91 |

| IK200 | 174.20 ± 15.22 | 94.00 ± 33.62 | 57.60 ± 21.76∗ | 17.80 ± 2.68 | 9.60 ± 2.88 | 6.40 ± 0.07 | 2.68 ± 0.08 | 22.68 ± 3.92 |

ALB, albumin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GLU, glucose; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; IC, immobilization-stressed control; IK 100, immobilization-stressed + KRG-WE 100 mg/kg body weight/d; IK 200, immobilization-stressed + KRG-WE 200 mg/kg body weight/d; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng; KRG-WE, Korean Red Ginseng water extract; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NC, normal control; SEM, standard error of the mean; TG, triglyceride; T-CHOL, total cholesterol; T-PRO, total protein.

3.4. Effects of KRG on mRNA and protein expression of key biomolecules of spermatogenesis in the testes of immobilization stress-induced rat

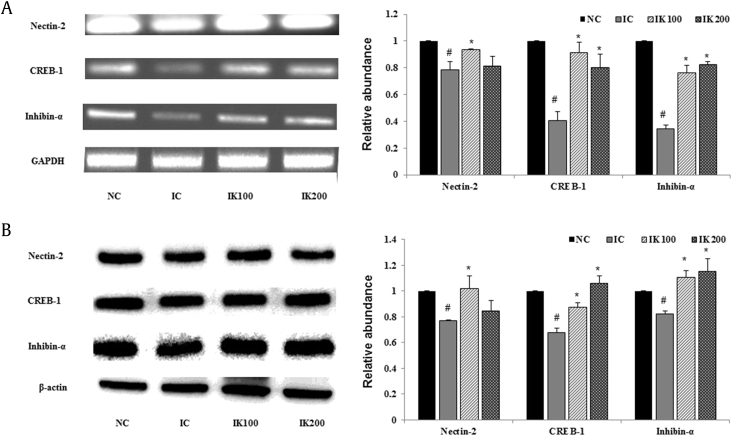

Compared with the NC group, the IC group showed suppressed levels of key molecules involved in spermatogenesis, such as nectin-2, cAMP responsive element binding protein 1(CREB-1), and inhibin-α (Fig. 2A). Quantification data revealed that treatment with KRG-WE significantly (p < 0.05) restored the decreased mRNA levels of nectin-2, CREB-1, and inhibin-α compared with that in the IC group. However, the mRNA expression of nectin-2 was not influenced by treatment with 200 mg/kg KRG. Furthermore, protein expression pattern of nectin-2, CREB-1, and inhibin-α was similar to their mRNA expression pattern (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effects of KRG on mRNA and protein expression levels of spermatogenesis-related molecules in rat testis. (A) The mRNA expression of nectin-2, CREB-1, and inhibin-α in the rat testicular tissue. The internal control used was GAPDH. Relative abundance level in three independent experiments normalized to that of GAPDH is shown (right side). (B) Protein expression of nectin-2, CREB-1, and inhibin-α in the testicular tissue was analyzed using Western blot analysis. Internal control used was β-actin. Relative abundance levels (fold) in three independent experiments normalized to β-actin is shown on right side. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (n = 8). Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's t test, using the SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). #p < 0.05 compared with the NC group and *p < 0.05 compared with the IC group. CREB-1, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) responsive element binding protein; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IC, immobilization-stressed control; IK100, immobilization-stressed and received 100 mg/kg body weight of KRG; IK200, immobilization-stressed and received 200 mg/kg body weight of KRG; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng; NC, normal control; SEM, standard error of the mean.

3.5. Effects of KRG on mRNA and protein expression of sex hormone receptors in the testes of immobilization stress-induced rats

Fig. 3 shows that the mRNA and protein expression level of sex hormone receptors, such as androgen receptor (AR), luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR), follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR), decreased significantly (p < 0.05) in the IC group compared with that in the NC group. Quantification data revealed that the mRNA level of AR, LHR, and FSHR significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in the IC group and was restored in the IK100 and IK200 groups significantly (p < 0.05, Fig. 3A). In agreement with the mRNA expression levels, the protein levels of AR, LHR, and FSHR significantly decreased in the IC group compared with that in the NC group (p < 0.05), and administration of KRG-WE (IK100 and IK200) attenuated the decreased expression levels of these genes (p < 0.05, Fig. 3B), except for AR protein expression. In the IC group, the decrease in the testicular mRNA expression level of FSHR was more pronounced than that of AR or LHR. Quantification data revealed that both 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg of KRG increased the suppressed protein levels of these receptors in immobilization-induced stress model.

Fig. 3.

Effects of KRG on mRNA and protein expression levels of sex hormone receptors in rat testis. (A) The mRNA expression of AR, LHR, and FSHR in the rat testicular tissue. The internal control used was GAPDH. Relative abundance level in three independent experiments normalized to that of GAPDH is shown (right panel). (B) Protein expression of AR, LHR, and FSHR in the testicular tissue was analyzed using Western blot analysis. The internal control used was β-actin. Relative abundance levels (fold) in three independent experiments normalized to β-actin is shown (right panel). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (n = 8). Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's t test, using the SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). #p < 0.05 compared with the NC group and *p < 0.05 compared with the IC group. AR, androgen receptor; FSHR, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IC, immobilization-stressed control; IK100, immobilization-stressed and received 100 mg/kg body weight of KRG; IK200, immobilization-stressed and received 200 mg/kg body weight of KRG; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng; LHR, luteinizing hormone receptor; NC: normal control; SEM, standard error of the mean.

3.6. Effects of KRG on mRNA and protein expression of antioxidant enzyme in the testes of immobilization stress-induced rats

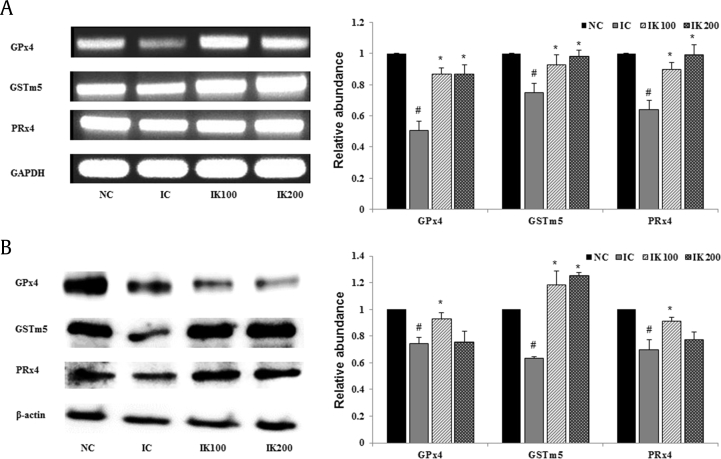

The mRNA expression levels of the antioxidant enzymes (GPx4, GSTm5, and PRx4) are shown in Fig. 4A. Quantification data revealed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the mRNA expression levels of GPx4, GSTm5, and PRx4 in the IC group compared with that in the NC group and amelioration of these levels in the KRG-WE treated groups (p < 0.05). As for the protein expression level, immobilization-induced stress significantly (p < 0.05) decreased GPx4, GSTm5, and PRx4 in agreement with mRNA levels, and administration of KRG-WE ameliorated these expression levels (Fig. 4B). The upregulation of the enzymes was in line with the expression levels of their corresponding mRNA. However, the KRG-WE administration at 100 mg/kg dose exhibited superior effects than at 200 mg/kg dose, particularly in the GPx4 and PRx4in protein expression.

Fig. 4.

Effects of KRG on mRNA and protein expression of antioxidant enzymes in rat testis. (A) The mRNA expression of glutathione peroxidase (GPx)-4, glutathione S-transferase (GST)-m5, and peroxiredoxin (PRx)-4 in the rat testicular tissue. The internal control used was GAPDH. Relative abundance level in three independent experiments normalized to that of GAPDH is shown (right panel). (B) Protein expression of glutathione peroxidase (GPx)-4, glutathione S-transferase (GST)-m5, and peroxiredoxin (PRx)-4 in the testicular tissue was analyzed using Western blot analysis. Internal control used was β-actin. Relative abundance levels (fold) in three independent experiments normalized to β-actin is shown (right panel). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (n = 8). Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's t test, using the SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). #p < 0.05 compared with the NC group and *p < 0.05 compared with the IC group. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IC, immobilization-stressed control; IK100, immobilization-stressed and received 100 mg/kg body weight of KRG; IK200, immobilization-stressed and received 200 mg/kg body weight of KRG; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng; NC: normal control; SEM, standard error of the mean.

3.7. UPLC analysis

As shown in Fig. 5, the representative chromatogram of KRG-WE by UPLC showed several peaks and up to 11 identifiable compounds, such as Rg1 (0.35 mg/g), Re (0.45 mg/g), Rf (1.15 mg/g), Rh1 (1.50 mg/g), Rg2s (1.71 mg/g), Rb1 (4.68 mg/g), Rc (2.00 mg/g), Rb2 (1.71 mg/g), Rd (0.96 mg/g), Rg3s (8.32 mg/g), and Rg3r (2.65 mg/g).

Fig. 5.

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) of ginsenosides in Korean red ginseng–water extract (KRG-WE). UPLC analysis was performed by an ACQUITY BEH C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) at column temperature of 40°C. The binary gradient elution system consisted of 0.001% phosphoric acid in water and 0.001% phosphoric acid in acetonitrile.

4. Discussion

Several modern lifestyle factors, such as prolonged working conditions, frequent drug usage, lack of nutrition, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, delayed marriage, exposure to environmental pollutants, and psychological stress, can affect male fertility [14]. Although studies have demonstrated that psychological stress adversely affects spermatogenesis [4], [20], [21], they were mostly limited to changes in the axis mechanisms; moreover, the animal models used were unsatisfactory [4], [22]. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to reproduce the modern chronic psychological stress using an emotional stress rat model, which was subjected to 8 wk of sub-chronic intermittent immobilization. We evaluated the changes in sperm quality and key spermatogenesis-related molecular markers, including oxidative defense parameters, after KRG administration.

Testes weight and epididymis weight in the IC group decreased significantly compared with that in the NC group. KRG increased the epididymis weight but not the testes weight. Fully matured sperms are recruited from the seminiferous tubules to the epididymis for ejaculation, and the weight of the epididymis reflects the rate of sperm production. Our data indicate that KRG improves the release of spermatozoa from spermatogonia into testicular gonocytes as well as increases the rate of sperm production.

KRG improves sperm motility and survival by protecting the blood–testis barrier and thus improves spermatogenesis, an important growth factor that facilitates communication between Sertoli cells and spermatogonia [18], [23]. Janevic et al. [24] detected linear negative association between perceived stress and sperm motility, sperm concentration, and observed morphologically normal spermatozoa in 193 men. In agreement with this study, our results in psychological stress mimic model showed decreased sperm motility. Furthermore, although no significant association was observed with sperm motility or morphological change, high stress levels resulted in 38% lower sperm concentration, 34% lower total sperm count, and 15% lower semen volume in 1,215 Danish men than in men with intermediate stress levels [21]. However, the authors indicated that the stress assessment relied on only four stress-related items, and the semen was collected only once from each man. Furthermore, they assessed stress 4–6 wk back in time, which is not optimal considering that the length of a spermatogenic cycle is 72 d in humans. Therefore, we used the 8-wk sub-chronic stress model, which fully covered the rat spermatogenic cycle (approximately 45 d) [25] and demonstrated that sperm motility and progressiveness significantly decreased in rats with sub-chronic intermittent immobilization stress but recovered after KRG administration. These results suggested that KRG can be a treatment option for idiopathic male infertility.

In blood chemistry analysis, our data showed that immobilization stress reduced the white blood cell count, which was restored following KRG administration. However, no significant results regarding other immunity or platelet function were observed. The intensity of immobilization stress may not have been sufficient for bone marrow suppression or immune suppression. A previous study reported that KRG inhibited platelet aggregation in human blood samples [26]. However, in our study, platelet count was normal in the stress model. Therefore, we could not expect additional positive effect after KRG administration. In-depth studies are necessary to evaluate the effects of KRG on blood chemistry. Furthermore, long-term chronic stress model should be employed in future studies.

For the lipid profile, TG, LDL-C, and total cholesterol (T-CHOL) significantly decreased in the immobilization induced-stress model and normalized after KRG administration. However, previous studies reported that the administration of KRG in mice that were fed a high-fat diet reduced T-CHOL levels and increased HDL-C levels [27], [28]. Thus, collectively, we suggest that KRG may regulate off-balanced lipid metabolism. Lipid profiles respond to diverse types of stress in various ways. On assessing the psychological stress at work, people in the highest quartile of stress had significantly higher levels of TG and lower levels of HDL-C than their colleagues in the lowest quartile at 5-yr follow-up [29]. Lipid profile analysis of immobilization mono-stress model has not been performed. A previous study with chronic unpredictable mild stress model induced by two 1-h restraints, overnight food and water restriction, and inversion of the light/dark cycles during 2 wk demonstrated that the serum concentration of TG was unaffected by stress, although T-CHOL and glucose levels increased compared with that in the control group [30]. In another chronic stress model in hyperlipidemic mouse induced by a combination of food deprivation, water deprivation, swimming in cold water, and sound and restraint stress, TG and T-CHOL levels increased compared with that in normal control and hyperlipidemic control [31]. The results of the lipid profile may have varied from our results due to different stress, the intensity of stress induction, and hyperlipidemic condition. Therefore, additional studies are necessary to elucidate the effects of KRG on lipid profile-related stress-induced male fertility.

It has been well documented that nectin-2, inhibin- α, and CREB-1 are involved in testicular function and act as major transcriptional factors in the process of spermatogenesis [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]. Nectin-2, an important adhesion molecule in the Sertoli germ cell junction, aids in the development of the matured spermatozoa and supports the maintenance of normal spermatogenesis [32], [33], [34]. CREB-1, expressed during the mitotic phase of spermatocytogenesis and the differentiation phase of spermiogenesis plays several roles in the development and normal function of the testis. Therefore, CREB-1 may be a key molecular regulator of testicular development and adult spermatogenesis in mice [37]. Inhibin-α is responsible for the negative feedback mechanisms that suppress FSH production from the pituitary gland and is important for the development of the round spermatid during the initial stages of spermatogenesis [35], [36]. In our study, sub-chronic intermittent immobilization stress decreased the mRNA and protein expression level of nectin-2, CREB-1, and inhibin-α in immobilization-induced stress rat model. These findings indicated that sub-chronic intermittent immobilization stress may affect the functional and signal transduction pathway involved in spermatogenesis. KRG significantly reversed the sub-chronic intermittent immobilization stress-induced mRNA and protein expression alterations, which suggests that KRG may regulate the key transcription factors and restore signal transduction that regulates spermatogenesis.

AR is a primary receptor of androgens, such as testosterone and 5α-dihydrotestosterone. Mutational defects of AR lead to androgen insensitivity and accompanying testicular cell dysfunction, which results in defects in spermatogenesis and even azoospermia [37], [38]. Therefore, quantitative (decline of the gene or protein expression) and qualitative (chromosomal defect) changes in AR could be one of the causes of male infertility. A study reported that in long-distance transported stress mice model, the mRNA and protein expression levels of AR and epididymis sperm count decreased compared with the values in the control group [39]; this result is consistent with our findings. This suggested that stress adversely affects reproductive organs and spermatozoa in adults by decreasing AR expression.

The low expression levels of LHR and FSHR, as well as of AR, also contribute to the inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and male infertility. In this axis, gonadotropin-releasing hormone binds to the gonadotrophs of the anterior pituitary to stimulate the secretion of LH and FSH. FSH acts on FSHR in Sertoli cells to aid spermatogenesis, while Leydig cells secrete testosterone in pulses in response to LH–LHR binding. This axis is directly affected by psychological stress, which leads to male infertility [4]. In LHR-knockout mice, spermatogenesis is arrested at round spermatids, adult-type Leydig cells are absent, testosterone production is dramatically decreased, and their sex organs are atrophic [40]. Furthermore, inactivation of FSHR mutation exhibited varying degrees of decrease in spermatogenesis. Thus, inactivation of FSHR or decreased FSHR expression hinders normal spermatogenesis [41]. As such, expression of LHR and FSHR is essential for normal testosterone production and maintaining normal spermatogenesis. In this study, the expression levels of proteins and mRNA of AR, LHR, and FSHR in the testicular tissue from rats subjected to sub-chronic intermittent immobilization stress were significantly downregulated. Treatment with KRG markedly prevented the downregulation of these receptors. These results indicate that KRG plays an important role in maintaining critical levels of sex hormone receptors, such as AR, LHR, and FSHR, which in turn ensures the proper functioning of androgens and normal spermatogenesis.

The natural balance between ROS and antioxidants is important in normal sperm physiological processes, such as capacitation, hyper activation, acrosome reactions, and signaling processes, to ensure appropriate fertilization. When the balance is disturbed, sperm function is significantly impaired, and these impairments result in male infertility through mechanisms involving the induction of peroxidative damage to the sperm plasma membrane, DNA damage, and apoptosis [42]. Emotional stress increases the levels of seminal plasma ROS, resulting in oxidative stress, which influences semen quality and fertility [43]. Sahin and Gumuslu [6] studied the brain antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in response to immobilization-induced stress models and observed decreased selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase activity and glutathione levels in immobilization stress group compared with that in the control group. Furthermore, lipid peroxidation marker (conjugated diene) significantly increased in the immobilization stress group [6].

The antioxidative enzymes GPx4, GSTm5, and PRx4 are important in numerous cellular processes and protection against peroxidative stress of lipids and nucleic acids in tissues [42], [44]. In addition to its antioxidative role, GPx4 acts as a structural protein for sperm maturation [45]. These enzymes were reported to be key antioxidant enzymes. Their levels were ameliorated by KRG administration, which improved infertility in aged rats [16], [17]. In agreement with this finding, GPx4 and GSTm5 were significantly reduced in immobilization stress groups compared with the control group, and KRG administration significantly restored the enzymatic function in our study. Similar effects were observed in mRNA expression levels. These results indicate that the neutralization capacity for ROS decreased in the immobilization stress group, and accumulated oxidative stress in immobilization stress rat impaired spermatogenesis and sperm function and that KRG can ameliorate these negative effects. The loss of function of PRx4 results in elevated spermatogenic cell death through oxidative stress [46]. In our study, PRx4 showed no expressional change in immobilization group or KRG group. The 8 wk of stress duration may not have been enough to induce PRx4 expression. Therefore, we plan to conduct a study with longer (chronic) duration of immobilization stress.

In our study, sub-chronic psychological stress induced impaired spermatogenesis through (1) increased oxidative stress by decreasing anti-oxidant enzyme expression; (2) sex hormone insensitivity by altered receptor expression; and (3) disturbance of spermatogenesis process by decreased function of spermatogenesis-related proteins. KRG ameliorated these effects. Although we did not evaluate how the changes in expression of key biomolecules are related, we believe that psychological stress directly affects the antioxidant enzyme, and the accumulated ROS results in DNA damage of sex hormone receptors and spermatogenesis-related molecules and ultimately impairs spermatogenesis. Further, our experiment showed several ginsenosides identified by UPLC analysis which were well reported to possess various pharmacological properties [12], [13], [14], [47]

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to create a sub-chronic psychological stress model with carefully controlled system (excluding other stress and conditions that are prone to feeding process errors) as well as the first study to reveal the beneficial role of KRG in the treatment of psychological stress-induced male infertility. Furthermore, we identified the mechanism underlying psychological stress-induced male infertility as emotional stress-induced oxidative stress, followed by DNA damage of sex hormone receptors and spermatogenesis-related molecules.

In conclusion, data from the present study suggest that KRG significantly attenuates sub-chronic psychological stress-induced sperm impairment by modulating the gene expression level of antioxidant enzymes and spermatogenic and sex hormone receptor-related proteins in immobilization-induced stress-rat model. Therefore, KRG is a potential candidate for preventing or treating psychological stress-induced male infertility.

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Korea Institute of Planning & Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries, Korea (Grant no: 113040-3).

References

- 1.Cocuzza M., Sikka S.C., Athayde K.S., Agarwal A. Clinical relevance of oxidative stress and sperm chromatin damage in male infertility: an evidence based analysis. International Braz J Urol. 2007;33:603–621. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382007000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brotman D.J., Golden S.H., Wittstein I.S. The cardiovascular toll of stress. Lancet. 2007;370:1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosmond R., Dallman M.F., Bjorntorp P. Stress-related cortisol secretion in men: relationships with abdominal obesity and endocrine, metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1853–1859. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nargund V.H. Effects of psychological stress on male fertility. Nature Reviews Urology. 2015;12:373–382. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2015.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirby E.D., Geraghty A.C., Ubuka T., Bentley G.E., Kaufer D. Stress increases putative gonadotropin inhibitory hormone and decreases luteinizing hormone in male rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2009;106:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901176106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahin E., Gumuslu S. Alterations in brain antioxidant status, protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation in response to different stress models. Behav Brain Res. 2004;155:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bitgul G., Tekmen I., Keles D., Oktay G. Protective effects of resveratrol against chronic immobilization stress on testis. ISRN Urology. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/278720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samarghandian S., Farkhondeh T., Samini F., Borji A. Protective effects of carvacrol against oxidative stress induced by chronic stress in rat's brain, liver, and kidney. Biochem Res Int. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/2645237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogler B.K., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. The efficacy of ginseng. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:567–575. doi: 10.1007/s002280050674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Z., Kim Y.W., Wu Y., Zhang J., Lee J.H., Li X., Cho I.J., Park S.M., Jung D.H., Yang C.H. Korean Red Ginseng attenuates anxiety-like behavior during ethanol withdrawal in rats. J Ginseng Res. 2014;38:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahady G.B., Gyllenhaal C., Fong H.H.S., Farnsworth N.R. Ginseng: a review of safety and efficacy. Nutr Clin Care. 2000;3:90–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retana-Marquez S., Salazar E.D., Velazquez-Moctezuma J. Effect of acute and chronic stress on masculine sexual behavior in the rat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:39–50. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attele A.S., Wu J.A., Yuan C.S. Ginseng pharmacology: multiple constituents and multiple actions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopalli S.R., Hwang S.Y., Won Y.J., Kim S.W., Cha K.M., Han C.K., Hong J.Y., Kim S.K. Korean red ginseng extract rejuvenates testicular ineffectiveness and sperm maturation process in aged rats by regulating redox proteins and oxidative defense mechanisms. Exp Gerontol. 2015;69:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramesh T., Kim S.W., Sung J.H., Hwang S.Y., Sohn S.H., Yoo S.K., Kim S.K. Effect of fermented Panax ginseng extract (GINST) on oxidative stress and antioxidant activities in major organs of aged rats. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Won Y.J., Kim B.K., Shin Y.K., Jung S.H., Yoo S.K., Hwang S.Y., Sung J.H., Kim S.K. Pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract (GINST) rescues testicular dysfunction in aged rats via redox-modulating proteins. Exp Gerontol. 2014;53:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kopalli S.R., Cha K.M., Jeong M.S., Lee S.H., Sung J.H., Seo S.K., Kim S.K. Pectinase-treated Panax ginseng ameliorates hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in GC-2 sperm cells and modulates testicular gene expression in aged rats. J Ginseng Res. 2016;40:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang S.Y., Kim W.J., Wee J.J., Choi J.S., Kim S.K. Panax ginseng improves survival and sperm quality in Guinea pigs exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo- p-dioxin. BJU International. 2004;94:663–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park H.W., In G., Han S.T., Lee M.W., Kim S.Y., Kim K.T., Cho B.G., Han G.H., Chang I.M. Simultaneous determination of 30 ginsenosides in Panax ginseng preparations using ultra performance liquid chromatography. J Ginseng Res. 2013;37:457–467. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seibel M.M., Taymor M.L. Emotional aspects of infertility. Fertility and Sterility. 1982;37:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordkap L., Jensen T.K., Hansen T.H., Lassen A.K., Bang U.N., Joensen M., Blomberg Jensen N.E., Skakkebæk N.E., Jørgensen N. Psychological stress and testicular function: a cross-sectional study of 1,215 Danish men. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.016. e171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong Q., Salva A., Sottas C.M., Niu E., Holmes M., Hardy M.P. Rapid glucocorticoid mediation of suppressed testosterone biosynthesis in male mice subjected to immobilization stress. J Androl. 2004;25:973–981. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb03170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang W.M., Park S.Y., Kim H.M., Park E.H., Park S.K., Chang M.S. Effects of Panax ginseng on glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) expression and spermatogenesis in rats. Phytother Res. 2011;25:308–311. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janevic T., Kahn L.G., Landsbergis P., Cirillo P.M., Cohn B.A., Liu X., Factor Litvak P. Effects of work and life stress on semen quality. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clermont Y. Kinetics of spermatogenesis in mammals: seminiferous epithelium cycle and spermatogonial renewal. Physiol Rev. 1972;52:198–236. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1972.52.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuo S.C., Teng C.M., Lee J.C., Ko F.N., Chen S.C., Wu T.S. Antiplatelet components in Panax ginseng. Planta Medica. 1990;56:164–167. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park Y., Kwon H.Y., Shimi M.K., Rhyu M.R., Lee Y. Improved lipid profile in ovariectomized rats by red ginseng extract. Pharmazie. 2011;66:450–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song Y.B., An Y.R., Kim S.J., Park H.W., Jung J.W., Kyung J.S., Hwang S.Y., Kim Y.S. Lipid metabolic effect of Korean red ginseng extract in mice fed on a high-fat diet. J Sci Food Agr. 2012;92:388–396. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garbarino S., Magnavita N. Work stress and metabolic syndrome in police officers. A prospective study. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortolani D., Garcia M.C., Melo Thomas L., Spadari Bratfisch R.C. Stress-induced endocrine response and anxiety: the effects of comfort food in rats. Stress. 2014;17:211–218. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2014.898059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu X., Hu S., Zhu L., Ding J., Zhou Y., Li G. Effects of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides on oxidative stress in hyperlipidemic mice following chronic composite psychological stress intervention. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:3445–3450. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrison M.E., Racaniello V.R. Molecular cloning and expression of a murine homolog of the human poliovirus receptor gene. J Virol. 1992;66:2807–2813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2807-2813.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mueller S., Rosenquist T.A., Takai Y., Bronson R.A., Wimmer E. Loss of nectin-2 at Sertoli-spermatid junctions leads to male infertility and correlates with severe spermatozoan head and midpiece malformation, impaired binding to the zona pellucida, and oocyte penetration. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1330–1340. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouchard M.J., Dong Y., McDermott B.M., Jr., Lam D.H., Brown K.R., Shelanski M., Bellve A.R., Racaniello V.R. Defects in nuclear and cytoskeletal morphology and mitochondrial localization in spermatozoa of mice lacking nectin-2, a component of cell-cell adherens junctions. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2865–2873. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2865-2873.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsueh A.J.W., Dahl K.D., Vaughan J., Tucker E., Rivier J., Bardin C.W., Vale W. Heterodimers and homodimers of inhibin subunits have different paracrine action in the modulation of luteinizing hormone-stimulated androgen biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1987;84:5082–5086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai K.L., Hua G.H., Ahmad S., Liang A.X., Han L., Wu C.J., Yang F.F., Yang L.G. Action mechanism of inhibin alpha-subunit on the development of Sertoli cells and first wave of spermatogenesis in mice. PloS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Don J., Stelzer G. The expanding family of CREB/CREM transcription factors that are involved with spermatogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;187:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mou L., Gui Y. A novel variant of androgen receptor is associated with idiopathic azoospermia. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:2915–2920. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun L.P., Song Y.P., Liu J.J., Liu X.R., Guo A.Z., Yang L.G. Differential expression of luteinizing hormone receptor, androgen receptor and heat-shock protein 70 in the testis of long-distance transported mice. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:9985–9993. doi: 10.4238/2015.August.21.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pakarainen T., Zhang F., Mäkelä S., Poutanen M., Huhtaniemi I. Testosterone replacement therapy induces spermatogenesis and partially restores fertility in luteinizing hormone receptor knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146:596–606. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tao Y.X., Segaloff D.L. Follicle stimulating hormone receptor mutations and reproductive disorders. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2009;89:115–131. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(09)89005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agarwal A., Virk G., Ong C., du Plessis S. Effect of oxidative stress on male reproduction. World J Mens Health. 2014;32:1–17. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2014.32.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eskiocak S., Gozen A.S., Yapar S.B., Tavas F., Kilic A.S., Eskiocak M. Glutathione and free sulphydryl content of seminal plasma in healthy medical students during and after exam stress. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2595–2600. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbieri E.R., Hidalgo M.E., Venegas A., Smith R., Lissi E.A. Varicocele-associated decrease in antioxidant defenses. J Androl. 1999;20:713–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ursini F., Heim S., Kiess M., Maiorino M., Roveri A., Wissing J., Flohe L. Dual function of the selenoprotein PHGPx during sperm maturation. Science. 1999;285:1393–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5432.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iuchi Y., Okada F., Tsunoda S., Kibe N., Shirasawa N., Ikawa M., Okabe M., Ikeda Y., Fujii J. Peroxiredoxin 4 knockout results in elevated spermatogenic cell death via oxidative stress. Biochem J. 2009;419:149–158. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bae E.A., Han M.J., Shin Y.W., Kim D.H. Inhibitory effects of Korean red ginseng and its genuine constituents ginsenosides Rg3, Rf, and Rh2 in mouse passive cutaneous anaphylaxis reaction and contact dermatitis models. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1862–1867. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]