Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) has made the problem of solving antibiotic resistance one of its priorities. The present study was designed to determine knowledge and attitude towards antibiotic use in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia in the period of July 2017 to October 2017. A self-administered questionnaire included question on demographic characteristics, antibiotic usage, knowledge and attitude towards antibiotics use. The data were analyzed using Statistical Package For the Social Science (SPSS).

Results

A total of 405 questionnaires were randomly distributed to the general public in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. However, only 387 of the participants completed the questionnaire making the response rate 95.5%. The majority of the participants (64.3%) know antibiotics effective against bacterial infections while (46.8%) of participants believed that antibiotics can be used to treat viral infections. A significant positive correlation was noted between the respondents’ antibiotic knowledge score and their attitude score (r = 0.523, p = 0.000). Significantly higher mean knowledge score of antibiotics was observed among study participants who were married, employed, participants working in health sector, high educational and high monthly income groups. Mean attitude score was found to be significantly high for females, participants working in health sector, high educational and high monthly income groups.

Conclusion

The participants who have good knowledge towards antibiotics use showed positive attitude towards antibiotics use. Some specific groups should to be targeted for educational intervention in terms of appropriate antibiotic use, such as those who have received a low level of education and are in receipt of a low monthly income.

Keywords: Knowledge, Attitude, Antibiotics use

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that resistance to antibiotics in European hospitals will increase costs by about €1.5 billion. Also, mortality will increase by 25,000 every year (World Health Organization, 2012). In 2013, the centre for disease control and prevention in the United States reported that each year 2 million people have a bacterial resistance to antibiotics in the USA, and at least 23,000 people have died from bacterial resistance to antibiotics (U.S Department of Health and Human Services, 2013).

In Saudi Arabia, antibiotics are classified as the third most commonly-prescribed form of medication (Al-Faris and Al Taweel, 1999). It is not legal in Saudi Arabia for pharmacists to sell antibiotics without a medical prescription (Bawazir, 1992). In fact, a study in Riyadh in 2011 reported that 77.6% of community pharmacies dispensed antibiotics to the public without a medical prescription (Abdulhak et al., 2011). Another study in Jeddah reported that 97.9% of pharmacies in the community pharmacies dispensed antibiotics without medical prescription (Al-Mohamadi et al., 2013).

Resistance to antibiotics can occur anywhere in the world, and it is considered a serious global health problem. Antibiotic resistance could greatly affect a country and could affect people of any age, leading to increasing costs and length of stay in hospital. The WHO has made the problem of solving antibiotic resistance one of its priorities (World Health Organization, 2015).

The WHO introduced a global campaign to increase the awareness of the public towards antibiotic resistance, and also to encourage the public to make appropriate use of antibiotics (World Health Organization, 2015).

There are a number of steps that can be taken to reduce antibiotic resistance among the general public. For example, antibiotics should not be used if a physician does not prescribe them, a course of antibiotics should be completed when prescribed by a physician, and antibiotics should not be shared with others (World Health Organization, 2015).

The public plays a significant role with regard to reducing the misuse of antibiotics and their excessive use. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the level of knowledge and attitude of the public towards the use of antibiotics in order to find out what education the public may need (Napolitano et al., 2013). The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge and attitude of the consumers towards antibiotic use in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia by cross-sectional study.

2. Materials and methods

A self-administered questionnaire was distributed to the participants. The study was conducted from June 2017 to October 2017 in Alkharj, which located in the center of Saudi Arabia, 70 km south of Riyadh. In this study, all data were collected from public places in Alkharj (e.g. shopping malls, hospitals, gyms, etc.). The inclusion criteria were Living in Alkharj and participants older than 18 years of age.

We randomly distributed 405 questionnaires to participants.

2.1. Instrument

The questionnaire was adapted from previous studies (Oh et al., 2010, Lim and Teh, 2012). The questionnaire was translated into Arabic and subjected to a process of forward and backward translation. The survey consisted of four parts. Part one consisted of questions aimed at identifying the demographic characteristics of the respondents and the second part contained questions about the usage of antibiotics. The third section contained 8 statements about the knowledge of the respondent with regard to antibiotic use. Participants were asked to respond either “Yes”, “No” or “Not Sure”. The fourth part related to the attitude towards antibiotic use. It consisted of 8 statements. The participants were required to answer according to a 5-point Likert scale (‘‘Strongly agree’’, ‘‘Agree’’, ‘‘Neutral’’, ‘‘Disagree’’, and ‘‘Strongly Disagree’’.). To simplify the analysis, ‘‘Strongly agree’’ and ‘‘Agree’’ were classified under the category of “Agree”, while ‘‘Disagree’’, and ‘‘Strongly Disagree’’ responses were classified under the category of “Disagree”.

2.2. Statistical analysis

The data was analysis using Statistical Package for Social Studies version 21 (SPSS 21 IBM, New York, USA). Descriptive statistics in the form of frequency distributions and percentages were obtained for each of the characteristics, and in terms of all questions relating to knowledge and attitude towards antibiotic use. To describe the degree of knowledge of the participants, a single point was assigned for every correct answer, and zero was assigned to wrong and Not Sure responses. The antibiotic knowledge score was obtained on a continuous variable by adding up the participant’s number of correct responses to 8 statements. Thus, a knowledge scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 8, was constructed based on the number of correct responses. The mean knowledge scores for bivariate variables (gender, marital status, employment status, work in the health sector, use of antibiotics during the last 12 months, and self-medication) were compared by using independent t tests. Similarly, the mean knowledge scores for multivariate variables (age, educational level and monthly income) were compared using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The attitude scores were calculated on a continuous scale by adding up the participant’s number of appropriate responses to 8 statements. One point was given for each appropriate response (strongly agree or agree for positive statements and strongly disagree or disagree for negative statements) and zero for each inappropriate and neutral response, with a maximum obtainable correct score of 8 for each respondent. The mean attitude scores for bivariate variables (gender, marital status, employment status, work in the health sector, use of antibiotics during the last 12 months, and self-medication) were compared by using independent t tests. Similarly, the mean attitude scores for multivariate variables (age, educational level and monthly income) were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Pearson’s correlation test was applied to analyze the relationship between knowledge and attitudes. For all statistical purposes, the level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Reults

3.1. Demographic characteristics and antibiotic usage of the participants

A total of 405 questionnaires were randomly distributed to the general public in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. However, only 387 of the participants completed the questionnaire making the response rate 95.5%. The largest percentage were in 18–30 year age group (48.6%) that constituted nearly half of the study participants. The sample distribution showed a high percentage of male (68.2%) participants compared to the female (31.8%) participants. More than half (56.3%) of the study participants were married, and possessed a university level qualification (56.8%). Most of the study participants were employed (62.8%) and 41.9% had a monthly salary of 10,001–20,000 SAR. Only 11.4% of the study participants worked in the health sector. More than three quarters (75.5%) of the study subjects had taken antibiotics in previous 12 months. Of the study participants, more than half (57.6%) took antibiotics without prescription (self-medication), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and antibiotic usage of the participants (N = 387).

| Variables | Number (N) | Percentage % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 18–30 | 188 | 48.6 |

| 31–40 | 136 | 35.1 | |

| 41–50 | 44 | 11.4 | |

| >50 | 19 | 4.9 | |

| Gender | Male | 264 | 68.2 |

| Female | 123 | 31.8 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 169 | 43.7 |

| Married | 218 | 56.3 | |

| Educational Level | Less than secondary | 20 | 5.2 |

| Secondary | 103 | 26.6 | |

| University | 220 | 56.8 | |

| Postgraduate | 44 | 11.5 | |

| Employment status | Employed | 243 | 62.8 |

| Not employed | 144 | 37.2 | |

| Monthly income (SAR) | Less than 5000 | 59 | 15.2 |

| 5000–10,000 | 97 | 25.1 | |

| 10,001–20,000 | 162 | 41.9 | |

| Above 20,000 | 69 | 17.8 | |

| Health sector | Yes | 44 | 11.4 |

| No | 343 | 88.6 | |

| Antibiotics usage in the last 12 months | Yes | 292 | 75.5 |

| No | 95 | 24.5 | |

| Antibiotics usage without Prescription (Self-medication) | Yes | 223 | 57.6 |

| No | 164 | 42.4 | |

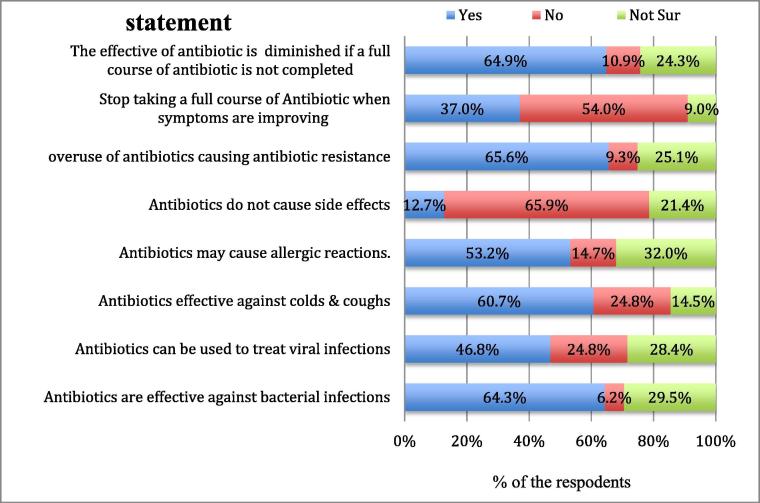

3.2. Knowledge of the study participants towards antibiotic use

The knowledge of antibiotics on the part of the study participant was elicited by using eight statements. When asked about the statement antibiotics are effective against bacterial infections, the majority of the participants (64.3%) answered correctly. On the other hand, less than half of the respondents (46.8%) incorrectly believed that antibiotics can be used to treat viral infections, while 28.4% were unsure of the answer. More than half of the participants (60.7%) incorrectly regarded antibiotics as being effective against colds and coughs. When asked whether or not antibiotics may cause allergic reactions, more than half of the participants (53.2%) responded correctly. A low percentage of the respondents (12.7%) incorrectly believed that antibiotics do not have side effects. When it came to the overuse of antibiotics causing antibiotic resistance, nearly two third of the participants (65.6%) responded correctly. Nearly 37% answered that they would stop taking a full course of antibiotics if the symptoms were improving, and nearly two thirds (64.9%) correctly mentioned that the effective of antibiotic is diminished if a full course of antibiotics is not completed, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Knowledge of the study participants towards antibiotic use.

3.3. Mean knowledge score

When knowledge of the antibiotics is measured on a continuous scale of 0–8, a mean score of 4.18 and a standard deviation of 2.14, with a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 8, was observed.

3.4. Comparison of mean knowledge scores between different groups

The mean knowledge score was found to be significantly high for employed (4.50 ± 2.23) compared to the unemployed (3.63 ± 1.84), (p = 0.001) respondents. Participants working in the health sector showed a significantly higher mean knowledge score (6.84 ± 1.66) towards antibiotic use compared to those who do not work in the health sector (3.83 ± 1.94), (p = 0.001). The married participants showed a significantly higher mean knowledge score (4.53 ± 2.24) compared to single participants (3.72 ± 1.94), (p = 0.001). There was not any significant association between the mean knowledge score and gender, participants who used antibiotics in the last 12 months and self-medication with antibiotics. A comparison of the mean knowledge score with regard to antibiotics across different age, educational level and monthly income groups, showed statistically significant differences. The 18–30 year old age group showed a significantly lower mean knowledge score (3.87 ± 2.1) compared to that of others. Participants with postgraduate degrees showed a significantly higher mean knowledge score (5.16 ± 1.98) compared to others. Also the participants with a monthly income above 20,000 SAR showed significant higher mean knowledge scores (4.77 ± 2.1) compared to others, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean knowledge score between different groups (N = 387).

| Mean | SD | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 4.16 | 2.21 | 0.863 |

| Female | 4.20 | 1.97 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 3.72 | 1.91 | 0.001 |

| Married | 4.53 | 2.24 | ||

| Age in years | 18–30 | 3.87 | 2.1 | 0.048 |

| 31–40 | 4.51 | 2.09 | ||

| 41–50 | 4.43 | 1.96 | ||

| >50 | 4.16 | 2.85 | ||

| Employment status | Employed | 4.50 | 2.23 | 0.001 |

| Not employed | 3.63 | 1.84 | ||

| Education level | Less than Secondary | 3.1 | 1.94 | 0.001 |

| Secondary | 3.37 | 1.87 | ||

| University | 4.45 | 2.15 | ||

| Postgraduate | 5.16 | 1.98 | ||

| Monthly Income (SAR) | Less than 5000 | 3.32 | 1.7 | 0.001 |

| 5000–10000 | 3.54 | 2.02 | ||

| 10001–20000 | 4.62 | 2.18 | ||

| Above 20,000 | 4.77 | 2.1 | ||

| Work in Health Sector | Yes | 6.84 | 1.66 | 0.001 |

| No | 3.83 | 1.94 | ||

| Antibiotics use in last 12 months | Yes | 4.26 | 2.14 | 0.172 |

| No | 3.92 | 2.12 | ||

| Antibiotics usage without Prescription (self-medication) | Yes | 4.27 | 2.18 | 0.294 |

| No | 4.04 | 2.08 | ||

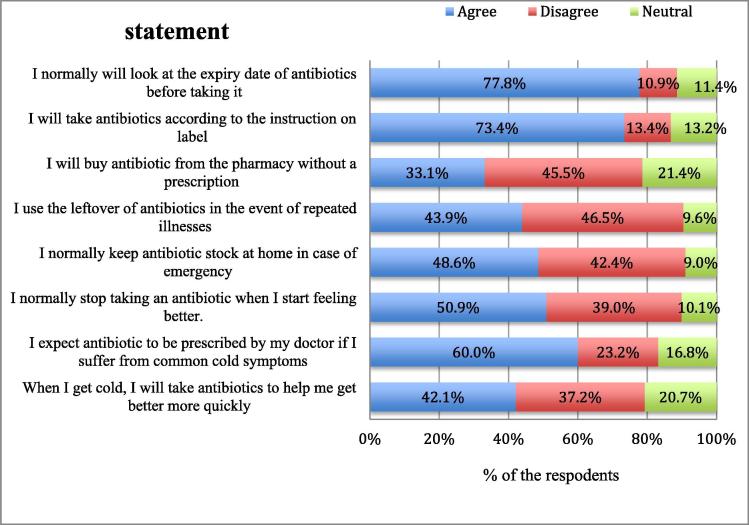

3.5. Attitude of the study participants towards antibiotic use

When asked about the use of antibiotics when having a cold, 42.1% incorrectly agreed that they took them. Sixty percent of the participants were expecting prescriptions for antibiotics from their doctor. More than half (50.9%) of the study participants expressed that they stopped taking antibiotics when they feel better. Nearly half of the respondents (48.6%) said that they keep a stock of antibiotics at home in case of emergency. Less than half of the participants (46.5%) correctly disagreed with regard to the use of left over antibiotics in the event of repeated illnesses. Nearly, 45.5% of the study participants correctly disagreed to buy antibiotics from a pharmacy without a prescription. 73.4% of the participants took antibiotics according to the instructions on the label. More than three-quarters (77.8%) looked at the expiry date of antibiotics before taking them, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Attitude of the study participants towards antibiotic use.

3.6. Mean attitude score

A mean attitude score of 3.85 with a standard deviation 2.15, and a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 8 was observed.

3.7. Comparison of mean attitude scores between different groups

The mean attitude score was found to be significantly higher for females (4.24 ± 2.07) compared to the males (3.67 ± 2.17), (p = 0.016). Similarly, participants working in the health sector (6.41 ± 1.87) showed a significantly higher mean attitude score towards antibiotics compared to those who do not work in health sector (3.52 ± 1.96), (p = 0.001). The study participants who had not used antibiotics in last 12 months, and those who did not self-medicate with regard to antibiotics without prescription, showed a significantly higher mean attitude score towards antibiotic use. There was no significant relationship between different ages and mean attitude scores. A comparison of mean attitude scores between different educational and monthly income groups showed significant differences (p < 0.05). The study participants with a university education (4.07 ± 2.26) and a postgraduate education (4.66 ± 2.32), showed a high mean attitude score towards antibiotics. Also the study participants having a monthly income of 10,001–20,000 SAR (4.05 ± 2.17) and above 20,000 SAR (4.51 ± 2.26), showed a high mean attitude score, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of mean attitude score between different groups (N = 387).

| Mean | SD | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 3.67 | 2.17 | 0.016 |

| Female | 4.24 | 2.07 | ||

| Marital Status | Single | 3.63 | 1.97 | 0.081 |

| Married | 4.02 | 2.28 | ||

| Age in years | 18–30 | 3.83 | 2.12 | 0.579 |

| 31–40 | 3.96 | 2.21 | ||

| 41–50 | 3.48 | 1.92 | ||

| >50 | 4.10 | 2.64 | ||

| Employment status | Employed | 3.94 | 2.26 | 0.256 |

| Not employed | 3.69 | 1.96 | ||

| Educational Level | Less than Secondary | 2.65 | 1.53 | 0.001 |

| Secondary | 3.27 | 1.70 | ||

| University | 4.07 | 2.26 | ||

| Postgraduate | 4.66 | 2.32 | ||

| Monthly Income(SAR) | Less than 5000 | 3.34 | 2.14 | 0.001 |

| 5000–10000 | 3.36 | 1.89 | ||

| 10001–20000 | 4.05 | 2.17 | ||

| Above 20,000 | 4.51 | 2.26 | ||

| Work in Health Sector | Yes | 6.41 | 1.87 | 0.001 |

| No | 3.52 | 1.96 | ||

| Antibiotics use in the last 12 months | Yes | 3.69 | 2.16 | 0.009 |

| No | 4.35 | 2.08 | ||

| Antibiotics usage without Prescription (self-medication) | Yes | 3.22 | 2.04 | 0.001 |

| No | 4.71 | 2.01 | ||

A significant positive correlation was noted between the respondents’ antibiotic knowledge score and their attitude score (r = 0.523, p = 0.000).

4. Discussion

Several reported studies have stated that the misuse of antibiotics is associated with the public knowledge of antibiotic use (Awad and Aboud, 2015, Chan et al., 2012). This study was conducted in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia, to determine the knowledge and attitude of the general public with regard to antibiotic use. The present study revealed that 75% of the participants in the study reported on their use of antibiotics in the 12 months prior to the survey. This is a high percentage when compared to a study in Poland, in which only 38% of the participants had used antibiotics in the previous 12 months (Mazińska et al., 2017). The study found that more than half of the participants 57.6% have used antibiotics without a prescription. This is higher than that reported in the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Poland. (McNulty et al., 2007, You et al., 2008, Oh et al., 2010, Mazińska et al., 2017). The misuse of antibiotics and bacterial resistance can be increased by antibiotic self-medication (Grigoryan et al., 2006).

It was found that 64.3% of the participants were aware that antibiotics can be used to treat bacterial infection. This is a higher rate than that found in similar studies in Jordan and South Korea (Shehadeh et al., 2012, Kim et al., 2011). In contrast, 46.8% of the respondents think that antibiotics can be used to treat viral infections. A lot of people cannot differentiate between bacteria and viruses. Consequently, they think that antibiotics can be used to treat both viral and bacterial infections (McKee et al., 1999).

The study found that more than half (50.9%) of the participants stated that they stopped taking antibiotics when they feel better. This is a higher rate than that found in a study in Sweden where only 4.5% stated that they stop taking antibiotics if they feel better (André et al., 2010). Stopping taking a full course of antibiotics will lead to an increase in the resistance of bacteria to antibiotics. The study showed that less than half (43.9%) of the participants agreed that they would use leftover antibiotics in the event of repeated illness. This is consistent with another study in Lebanon. However, it is a considerably higher rate compared to that of another study in Malaysia at only 3.2% (Mouhieddine et al., 2015, Oh et al., 2010). The WHO reported that using leftover antibiotics could increase the resistance to antibiotics (World Health Organization, 2012).

In the present study, it was found that married participants and employed participants were associated significantly with higher level of knowledge with regard to antibiotic use compared to single and unemployed participants. That is similar to a study in Jeddah which showed that the married participants were significantly associated with a good knowledge of antibiotic use compared to single participants (Bahlas et al., 2016). In addition, previous study in Italy noted that there was a significant association between unemployed respondents and low levels of knowledge with regard to antibiotic use (Napolitano et al., 2013). Furthermore the study indicated there was a statistically significant difference in knowledge with regard to antibiotic use among different age groups. Those aged 18–30 years were significantly less knowledgeable about of antibiotics. This is agreement with the results of a study in Malaysia which indicated that the younger generation between the ages of 18 and 30 had poor knowledge regarding antibiotic use (Oh et al., 2010).

The knowledge and attitude with regard to antibiotics across different educational and monthly income groups showed statistically significant differences. Those respondents who had received a higher education and who earned a higher monthly income showed a higher level of knowledge and a more positive attitude toward antibiotics use. There have been many studies reported in Jeddah, Malaysia, Lithuania, Italy, Hong Kong and Poland which stated that education level and monthly income is significantly associated with the knowledge of antibiotics and a positive attitude towards antibiotic use (Bahlas et al., 2016, Lim and Teh, 2012, Pavydė et al., 2015, Napolitano et al., 2013, You et al., 2008, Mazińska et al., 2017). Therefore, those individual with low levels of education and low monthly income should take priority with regard to any health education in terms of knowledge and attitude towards antibiotic use. A previous study in Hong Kong showed that the female gender were significantly associated with positive attitudes towards antibiotic use (You et al., 2008). The present study demonstrated that the female participants showed good attitude towards antibiotics use compared to male participants.

The study found that there was a significant positive correlation between the respondents’ knowledge and their attitude towards antibiotics use. This suggests that those participants who have a good knowledge with regard to antibiotic use have a positive attitude towards antibiotic use. This is confirmed by other studies in Lebanon, Malaysia, South Korea and Sweden (Mouhieddine et al., 2015, Lim and Teh, 2012, Kim et al., 2011, André et al., 2010).

4.1. Limitation of the study

The survey omitted those who could not speak Arabic as the questionnaire was in that language. The study was limited to members of the public who live in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia. The majority in the study participants were young and male. Also, another limitation is the study is cross- sectional represent one point in time and do not reflect any change in knowledge and attitude over time

5. Conclusion

The participants who have a good knowledge with regard to antibiotic use showed a positive attitude towards antibiotics use. Higher education, working in the medical field and a high monthly income were associated significantly with good knowledge and positive attitude towards antibiotic use. However, single and unemployed participants showed a significant association with low knowledge with regard to antibiotic use. The findings of this study may be useful in order to help develop intervention through an increase in peoples’ awareness regarding the risk of inappropriate use of antibiotics, and to decrease misconceptions regarding antibiotic use.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank DR Ka Keat Lim and DR Mohamed Azmi Hassali for their cooperation. Also we would like to thank all of the participants in the study.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Riyadh Colleges of Dentistry and Pharmacy (RCsDP) with the following number RC/IRB/2016/592.

Funding

No funding sources.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abdulhak A.A.B., Al Tannir M.A., Almansor M.A., Almohaya M.S., Onazi A.S., Marei M.A., Aldossary O.F., Obeidat S.A., Obeidat M.A., Riaz M.S., Tleyjeh I.M. Non prescribed sale of antibiotics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):538. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Faris E.A., Al Taweel A. Audit of prescribing patterns in Saudi primary health care: what lessons can be learned? Ann. Saudi Med. 1999;19(4):317–321. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1999.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohamadi A., Badr A., Mahfouz L.B., Samargandi D., Al Ahdal A. Dispensing medications without prescription at Saudi community pharmacy: extent and perception. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 2013;21(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André M., Vernby Å., Berg J., Lundborg C.S. A survey of public knowledge and awareness related to antibiotic use and resistance in Sweden. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65(6):1292–1296. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad A.I., Aboud E.A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards antibiotic use among the public in Kuwait. PloS one. 2015;10(2):e0117910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahlas R., Ramadan I., Bahlas A., Bajunaid N., Al-Ahmadi J., Qasem M., Bahy K. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards the use of antibiotics. Life Sci. J. 2016;13(1) [Google Scholar]

- Bawazir S.A. Prescribing pattern at community pharmacies in Saudi Arabia. Int. Pharm. J. 1992;6:222. [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y.H., Fan M.M., Fok C.M., Lok Z.L., Ni M., Sin C.F., Wong K.K., Wong S.M., Yeung R., Yeung T.T., Chow W.C. Antibiotics nonadherence and knowledge in a community with the world’s leading prevalence of antibiotics resistance: implications for public health intervention. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2012;40(2):113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan L., Burgerhof J.G., Haaijer-Ruskamp F.M., Degener J.E., Deschepper R., Monnet D.L., Di Matteo A., Scicluna E.A., Bara A.C., Lundborg C.S., Birkin J. Is self-medication with antibiotics in Europe driven by prescribed use? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;59(1):152–156. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.S., Moon S., Kim E.J. Public knowledge and attitudes regarding antibiotic use in South Korea. J. Kor. Acad. Nursing. 2011;41(6):742–749. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2011.41.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K.K., Teh C.C. A cross sectional study of public knowledge and attitude towards antibiotics in Putrajaya, Malaysia. Southern Med. Rev. 2012;5(2):26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazińska B., Strużycka I., Hryniewicz W. Surveys of public knowledge and attitudes with regard to antibiotics in Poland: Did the European Antibiotic Awareness Day campaigns change attitudes? PloS One. 2017;12(2):e0172146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M.D., Mills L., Arch G., III Antibiotic use for the treatment of upper respiratory infections in a diverse community. J. Fam. Pract. 1999;48(12):993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty C.A., Boyle P., Nichols T., Clappison P., Davey P. The public's attitudes to and compliance with antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60(suppl_1):i63–i68. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouhieddine T.H., Olleik Z., Itani M.M., Kawtharani S., Nassar H., Hassoun R., Houmani Z., El Zein Z., Fakih R., Mortada I.K., Mohsen Y. Assessing the Lebanese population for their knowledge, attitudes and practices of antibiotic usage. J. Infect. Public Health. 2015;8(1):20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano F., Izzo M.T., Di Giuseppe G., Angelillo I.F. Public knowledge, attitudes, and experience regarding the use of antibiotics in Italy. PloS One. 2013;8(12):e84177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh A.L., Hassali M.A., Al-Haddad M.S., Sulaiman S.A.S., Shafie A.A., Awaisu A. Public knowledge and attitudes towards antibiotic usage: a cross-sectional study among the general public in the state of Penang, Malaysia. J. Infect. Develop. Countries. 2010;5(05):338–347. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavydė E., Veikutis V., Mačiulienė A., Mačiulis V., Petrikonis K., Stankevičius E. Public knowledge, beliefs and behavior on antibiotic use and self-medication in Lithuania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015;12(6):7002–7016. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120607002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehadeh M., Suaifan G., Darwish R.M., Wazaify M., Zaru L., Alja’fari S. Knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding antibiotics use and misuse among adults in the community of Jordan. A pilot study. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 2012;20(2):125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. (assessed 20 May 2017).

- World Health Organization, 2012. The evolving threat of antimicrobial resistance: options for action. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/ 2012/9789241503181_eng.pdf. (accessed: 7 May 2017).

- World Health Organization, 2015. Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public Awareness Survey. Oslo, Norway: WHO. Available from: http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/baselinesurveynov2015/en/(accessed 10 May 2017).

- You J.H.S., Yau B., Choi K.C., Chau C.T.S., Huang Q.R., Lee S.S. Public knowledge, attitudes and behavior on antibiotic use: a telephone survey in Hong Kong. Infection. 2008;36(2):153–157. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-7214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]