Abstract

Trichoscopy (dermoscopy of the hair and scalp) is a technique that improves diagnostic accuracy and follow-up with hair and scalp disorders. Although several studies of trichoscopy have been made in Caucasian and Asian populations, little has been published regarding trichoscopy findings in skin of color, despite the great prevalence of hair diseases in populations with this kind of skin. The aim of this review was to describe the trichoscopic features of normal scalp and of hair disorders in patients with dark skin phototypes. This will help dermatologists to distinguish between unique trichoscopic features of dark skin, and allow them to provide more accurate diagnoses and treatments for these patients.

Keywords: Trichoscopy, Dermoscopy, Nonscarring alopecia, Scarring alopecia, Androgenetic alopecia, Alopecia areata, Tinea capitis, Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, Lichen planopilaris, Frontal fibrosing alopecia

Introduction

Trichoscopy is the dermoscopic examination of the hair and scalp [1, 2]. It is a fast, noninvasive, and cost-efficient technique that improves diagnostic accuracy and follow-up with hair and scalp disorders [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8].

Human hair has been classified into three distinct groups according to ethnic origin: Asian, Caucasian, and African [9, 10, 11]. Several studies have been published about trichoscopy in Caucasian and Asian populations; however, little has been published regarding dermatoscopic findings in hair disorders of dark-skinned individuals [4].

Hair and scalp disorders are a considerable problem among patients of African descent [3, 11, 12]. The distinct properties of the hair and scalp of this patient population warrant further investigation into their unique trichoscopic patterns [3, 4, 13, 14]. The aim of this review was to describe the trichoscopic features of the normal scalp and of hair disorders in patients with dark skin phototypes, including but not limited to patients of African descent.

Materials and Methods

A literature search of PubMed/MEDLINE to identify case reports, case series, review articles, and clinical trials using the search terms (hair dermoscopy, trichoscopy, or trichoscopic) was performed. The search was limited to English-language studies.

The clinical and dermoscopic images in this paper were taken and stored using the handyscope (FotoFinder Systems, Bad Birnbach, Germany) attached to the iPhone 4S (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) and the FotoFinder videodermatoscope (FotoFinder Systems).

Results and Discussion

In this review, we searched the literature spanning from 1993 to 2017 on trichoscopy of dark-skinned individuals. All full articles from this search were reviewed and included if pertinent. After the initial search, we reviewed the references of all articles to discover any cases not uncovered in our initial PubMed/MEDLINE search. Sixty-one papers on trichoscopy of dark-skinned individuals with hair and scalp disorders were included. Three books on trichoscopy were also included and reviewed [15, 16, 17].

Normal Dark-Skinned Scalp

The color of the scalp on trichoscopy varies between light brown and dark black, and does not necessarily correlate with the actual color of the skin [4]. A perifollicular pigmented network or honeycomb pattern is normally visible in the whole scalp [4, 18]. It is formed by pigmented lines (corresponding to rete ridge melanocytes) that surround hypochromic areas (fewer melanocytes residing in the suprapapillary epidermis) [18, 19] (Fig. 1). A unique feature of the pigmented scalp is the presence of pinpoint white dots, first described by Kossard and Zagarella [20] as a sign of fibrosis in scarring alopecia, but better characterized by Abraham et al. [18] in 2010 as a feature of the normal scalp instead (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Normal dark-skinned scalp. Trichoscopy shows a perifollicular pigmented network or honeycomb pattern (pigmented lines that surround hypochromic areas).

Table 1.

Unique features of dark scalp and their variations

| Features of dark scalp | Variations |

|---|---|

| Perifollicular pigmented network or honeycomb pattern | Disrupted in discoid lupus erythematosus and in secondary scarring alopecias |

| Pinpoint white dots | Nonscarring alopecias: regular distribution and often containing miniaturized or broken hair shafts |

| Scarring alopecias: irregular distribution; the scalp between the dots contains irregular white patches | |

| Erythema | Common, but the vascular patterns are hard to see |

Pinpoint white dots are small (0.2- to 0.3-mm) white dots that are regularly distributed between the follicular units [1, 4] (Fig. 2). Reflectance confocal microscopy showed that these dots correspond to acrosyringeal and follicular openings [21].

Fig. 2.

Normal dark-skinned scalp. Trichoscopy shows pinpoint white dots, regularly distributed between the follicular units.

The scalp of individuals of African descent often presents asterisk-like macules, scales, and residues of styling products, and erythema is quite common [5]. The hair density is significantly lower than in Caucasians, but the hair shaft diameter is larger and the shaft is flat in shape [10, 11, 22]. Follicular units most commonly consist of a couple of hairs emerging together [21]. African hair is prone to develop knots, longitudinal fissures, and splits along the hair shaft [23].

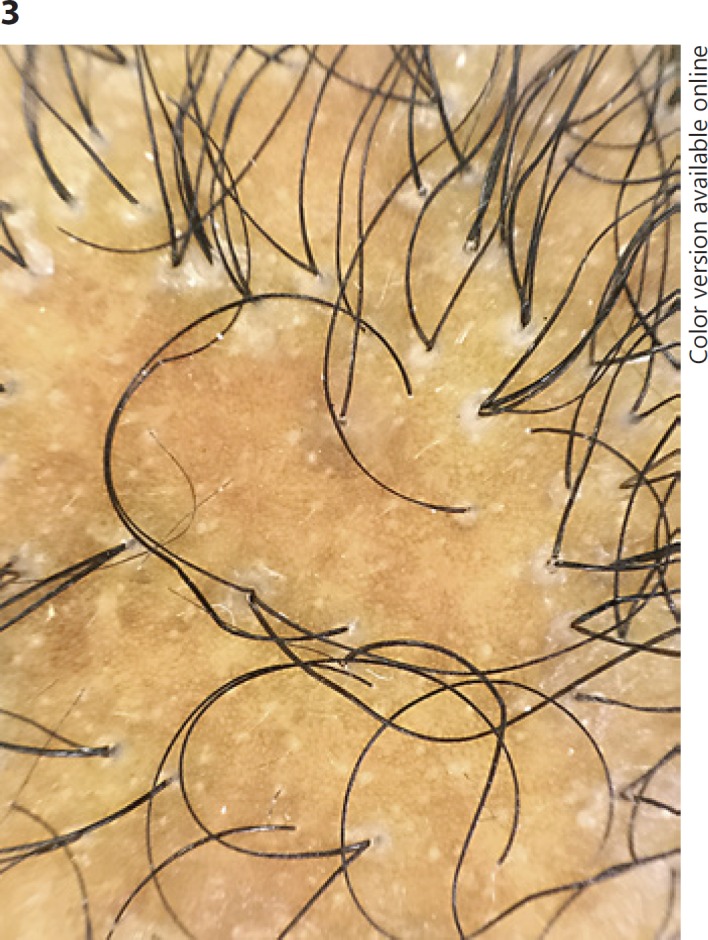

Nonscarring versus Scarring Alopecias

In dark-skinned individuals, the presence of pinpoint white dots makes distinguishing scarring from nonscarring alopecia more difficult than in nonpigmented scalp, as the loss of follicular openings is not immediately evident [4]. In nonscarring alopecias, the pinpoint white dots' distribution is very regular, and the dots often contain miniaturized or broken hair shafts. In scarring alopecias, the pinpoint white dots have an irregular distribution, and the scalp between the dots contains irregular white patches (follicular scars) [4, 10] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Scarring alopecia. Trichoscopy shows pinpoint white dots with an irregular distribution, and irregular white patches.

Nonscarring Alopecias

Androgenetic Alopecia

On trichoscopy, the honeycomb pattern is preserved, and the pinpoint white dots are regularly distributed [4, 24]. The diagnostic criteria are the same as in Caucasians: more than 20% hair shaft variability and presence of short, thin (0.03 mm in diameter) regrowing hairs in the frontal scalp [4, 25, 26, 27] (Fig. 4). Chiramel et al. [26] reported that the peripilar sign, commonly found in Caucasian patients with early androgenetic alopecia, is uncommon (6%) in patients from North India, possibly owing to the difficulty in identifying this feature in dark skin. The peripilar sign is a brown halo around the emergence of the hair shaft, and it pathologically corresponds to perifollicular inflammation [15]. Bhamla et al. [28] found that trichoscopy was 75% sensitive and 61.54% specific in diagnosing early female pattern hair loss.

Fig. 4.

Androgenetic alopecia. Trichoscopy shows hair diameter variability and a preserved honeycomb pattern.

Alopecia Areata

Trichoscopy in alopecia areata shows preservation of the honeycomb-like pigmented network in affected and unaffected scalp [2, 29, 30]. Yellow dots are uncommon, as empty follicles appear white instead of yellow [26, 29]. Although some researchers (Bapu et al. [31], Mane et al. [32], and Guttikonda et al. [33]) reported yellow dots as the most common dermoscopic feature of alopecia areata in dark-skinned Indian patients, their pictures document white rather than yellow dots.

Other dermoscopic features of alopecia areata are the same as in Caucasian and Asian patients and include exclamation mark hairs, broken hairs, black dots, circle hairs, and coudability [4, 16, 17, 29] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Alopecia areata. Trichoscopy shows preservation of the honeycomb-like pigmented network, numerous white dots, exclamation mark hairs, broken hairs, and black dots.

Tinea Capitis

The clinical diagnosis of tinea capitis in dark-skinned scalp can represent a diagnostic challenge as erythema of the scalp is more difficult to appreciate [34]. Corkscrew hairs, which appear as irregularly twisted short hairs, are a characteristic finding in patients of African descent [4, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38] (Fig. 6). Their shape is related to the shape of African hair, and they were not detected in tinea capitis patients with black scalp but different ethnicity [34]. For instance, Amer et al. [39] reported that the most frequent dermoscopic feature of tinea capitis in an Egyptian population was comma hairs, first described by Slowinska et al. [40], followed by zigzag hairs, found in 60 and 30% of their patients, respectively. Other features of tinea capitis reported in black scalp include black dots, hair casts, broken hairs, clip or question mark hairs, and Morse code-shaped hair [4, 34, 39, 41].

Fig. 6.

Tinea capitis. Trichoscopy shows corkscrew hairs and broken hairs.

Trichotillomania

Few reports have been published about the trichoscopic characteristics of trichotillomania in dark skin [26, 42, 43, 44]. The honeycomb-like pigmented network is preserved and pinpoint white dots are regularly arranged [19, 26]. The most important features include the presence of broken hairs of different lengths, short hairs with trichoptilosis (split ends), black dots, irregular coiled hairs, upright regrowing hairs, question mark hairs, flame hairs, the “V” sign, tulip hairs, and hair powder [26, 42, 43, 44, 45].

Early Nonscarring Alopecia - Late Scarring Alopecia

Dissecting Cellulitis

Although dissecting cellulitis is mostly seen in young males of Afro-American or Hispanic descent, most of the literature on trichoscopy of this condition is based on Caucasian patients [4, 9, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51]. Trichoscopy of the alopecic patches shows features of nonscarring alopecia, with regularly distributed pinpoint white dots, enlarged plugged follicular openings and black dots, and broken hairs [4]. In end-stage disease, scarring lesions may appear, and they are characterized by confluent ivory-white areas lacking follicular ostia, indistinguishable from other scarring alopecias [6].

Traction Alopecia

Trichoscopy in the early stage of the disease shows preservation of the honeycomb pattern, regularly distributed pinpoint white dots, and reduced hair density, with numerous miniaturized hairs [4]. The advanced stage of the disease is characterized by pinpoint white dots with an irregular distribution and the presence of irregular white patches [4, 9]. Early diagnosis of traction alopecia is important, as the hair loss is reversible [10, 45, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56]. The presence of hair casts surrounding the hair shafts at the periphery of the alopecic patch indicates ongoing traction and suggests that the alopecia is likely to progress [57] (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Traction alopecia. Trichoscopy shows a cast surrounding a hair shaft.

Scarring Alopecia

Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) is a very common cause of scarring alopecia among women of African descent [58, 59, 60, 61]. Trichoscopy of CCCA shows preservation of the honeycomb pigmented network and pinpoint white dots with an irregular distribution [4, 18]. A peripilar gray-white halo around the emergence of the hairs is a specific and sensitive sign for the diagnosis of CCCA. These peripilar white halos correlate on histopathology with the follicular ostia of both terminal and vellus follicles surrounded by perifollicular fibrosis [62].

Other dermoscopic features of CCCA include hair shaft variability, perifollicular erythema, broken hairs as black dots inside the follicular opening or as short broken shafts, pigmented asterisk-like macules with sparse terminal and vellus-like hairs, and scattered white patches [4, 62, 63, 64] (Fig. 8). Dermoscopic features directing biopsy in CCCA include one or two hairs emerging together, surrounded by a white halo [4].

Fig. 8.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Trichoscopy shows preservation of the honeycomb pigmented network and pinpoint white dots with an irregular distribution. Peripilar gray-white halos are seen around the emergence of the hairs. Hair shaft variability, perifollicular erythema, and scattered white patches are also present.

Lichen Planopilaris

Trichoscopy of lichen planopilaris shows preservation of the honeycomb pattern pigmented network with pinpoint white dots that give rise to a starry sky appearance (starry sky pattern) [4, 10, 15]. Peripilar casts (concentrically arranged and tightly adherent scales around the emerging hair shaft) are typically observed around the terminal hairs within and surrounding the alopecic patches [1, 4, 65, 66, 67] (Fig. 9). They are only appreciated using dry dermoscopy [1]. Casts often surround a tuft of 2 or more hairs emerging together [1, 4]. Other common features are a few broken hairs, black dots, and pili torti [4, 65, 66, 67].

Fig. 9.

Lichen planopilaris. Trichoscopy shows preservation of the honeycomb pattern pigmented network with pinpoint white and multiple peripilar casts (including casts surrounding tufts of 2 or 3 hairs emerging together).

Perifollicular blue-gray dots with an annular pattern (which pathologically corresponds to melanin particles within melanophages or free on the papillary dermis) or “target” pattern (which results from the accumulation of melanophages around the hair follicles) are occasionally seen [4, 68]. Dermoscopic features directing biopsy in lichen planopilaris include a tuft of 2 or 3 hairs surrounded by a peripilar cast [4].

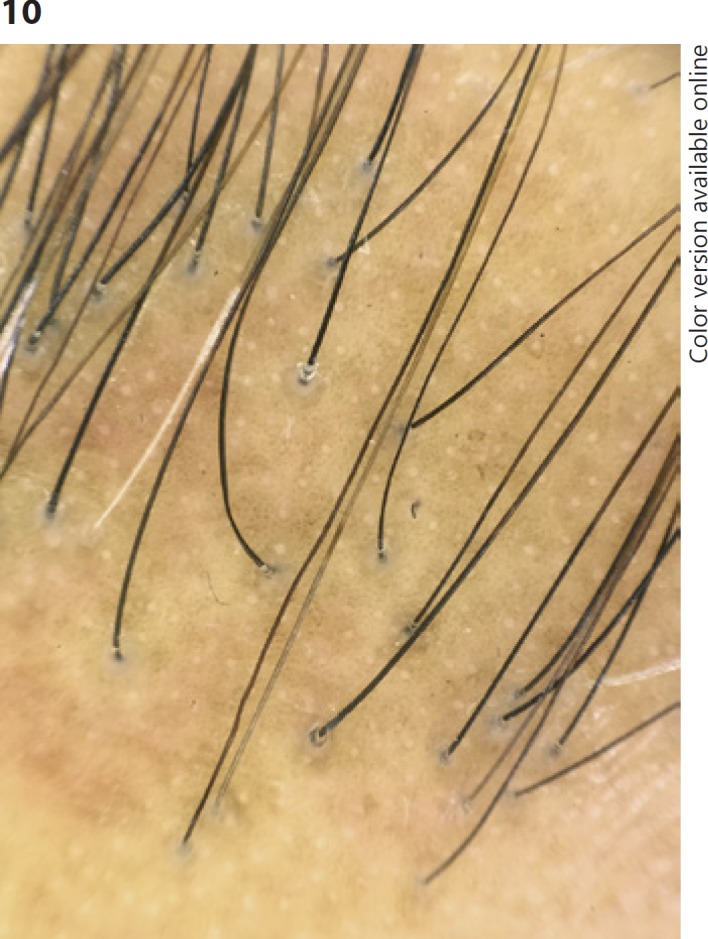

Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is commonly associated with eyebrow and limb involvement [68, 69, 70, 71]. Facial papules [72, 73, 74, 75] and lichen planus pigmentosus are frequent in dark-skinned individuals [75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80].

Trichoscopy of the receding hairline shows absence of vellus hairs and presence of terminal hairs with peripilar casts, which may be subtle or very prominent [4, 81] (Fig. 10). Black dots, pili torti (flattened hair shafts that twist 180° at irregular intervals), follicular hyperpigmentation, and broken hairs can also be seen [4, 69, 71, 80]. Trichoscopy of the alopecic band shows irregularly arranged pinpoint white dots and white patches [69]. The dermoscopic feature directing biopsy in FFA is the same as in lichen planopilaris, a hair with peripilar casts [4].

Fig. 10.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia. Trichoscopy of the receding hairline shows absence of vellus hairs and presence of terminal hairs with peripilar casts. The honeycomb pigmented network and pinpoint white dots are also evident.

Pirmez et al. [79] reported the dermoscopic findings of lichen planus pigmentosus associated with FFA, which included four distinct patterns of pigmentation: a pseudonetwork, a dotted pattern, speckled blue-gray dots, and blue-gray dots arranged in circles.

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus

Trichoscopy of affected areas shows loss of pigmentation with disruption of the honeycomb pattern and reduced or absent pinpoint white dots [4, 68]. Follicular keratotic plugs and peripilar casts are commonly observed [65] (Fig. 11). Follicular keratotic plugs pathologically correlate with hyperkeratosis and significant keratotic plugging of follicular ostia at the level of the infundibulum [4, 82]. Blue-gray dots arranged in a speckled pattern are typical of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and are caused by pigment incontinence involving both the hair follicle and the interfollicular epidermis [4, 68]. Other dermoscopic features of DLE are the presence of follicular red dots (erythematous polycyclic, concentric structures which correspond to dilated follicular openings surrounded by dilated vessels), white patches, and variable scaling [82]. Enlarged branching vessels are also common, and their presence strongly suggests a diagnosis of DLE [65, 82, 83]. Abedini et al. [84] reported that the presence of both tortuous branching vessels and hyperkeratotic follicular scales was 100% specific for the diagnosis of DLE in Iranian patients (phototypes III–V). Dermoscopic features directing biopsy in DLE include keratotic plugs, red dots, and peripilar casts [4].

Fig. 11.

Discoid lupus erythematosus. Trichoscopy shows loss of pigmentation with disruption of the honeycomb pattern, absence of pinpoint white dots, and follicular keratotic plugs. White patches are also present.

Acne Keloidalis Nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic inflammatory condition that most commonly affects young men of African or Hispanic descent [85]. It is believed that shaving of short, tightly curled hair may be a precipitating factor for the development of the disease [9].

Trichoscopy shows broken hairs with tufting, ingrown hairs, and peripilar casts [1]. Ingrown hair can be due to extrafollicular and transfollicular penetration of the skin, usually secondary to a sharp-cut end of the terminal curly African hair [85, 86].

Folliculitis Decalvans

Trichoscopy typically shows multiple hairs (normally 6 or more) emerging from a single dilated follicular orifice (polytrichia) and surrounded by a scale collarette [1, 87]. Other trichoscopic findings include focal disruption of the honeycomb pattern with loss of pigmentation, reduction of the number of pinpoint white dots, irregular white patches, yellowish tubular scaling, scalp erythema, crusting, and follicular pustules [87].

Acquired Hair Shaft Abnormalities

Hair Breakage

Hair breakage is a common problem in individuals of African descent due to the intrinsic characteristics of their hair (more fragile, reduced tensile strength, and reaching its breaking point earlier than the hair of other racial groups) and also secondary to hair shaft damage caused by excessive styling and straightening [3, 4, 88].

Trichoscopy of the scalp or of the shed broken hairs shows trichorrhexis nodosa, with swelling nodes of the hair fibers and splitting of their tips (distal trichoptilosis); the trichoptilosis may also be centrally located [3, 89, 90, 91, 92] (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Hair breakage. Trichoscopy of a shed broken hair shows central trichoptilosis (a longitudinal split in the central part of the shaft).

Conclusions

In the last years, trichoscopy has become a very useful tool in the diagnosis of hair and scalp disorders. However, most of the studies have been done in Caucasian or Asian populations, and although most dermoscopic features are similar in dark-skinned individuals, there are some characteristics of the pigmented scalp that are unique and important to be known.

This paper reviewed the available literature on dark-skinned hair and scalp disorders, adding personal cases and information, and showing all their specific trichoscopic features.

Disclosure Statement

A. Tosti: CRC Press, author royalties; FotoFinder: consultant.

References

- 1.Miteva M, Tosti A. Hair and scalp dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1040–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olszewska M, Rudnicka L, Rakowska A, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Slowinska M. Trichoscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1007. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quaresma MV, Martinez Velasco MA, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99–104. doi: 10.1159/000436981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin NC, Tosti A. A systematic approach to Afro-textured hair disorders: dermatoscopy and when to biopsy. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miteva M, Tosti A. Dermatoscopy of hair shaft disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A, Slowinska M. Trichoscopy update 2011. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:82–88. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2011.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Slowinska M. Trichoscopy: a new method for diagnosing hair loss. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:651–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikam VV, Mehta HH. A nonrandomized study of trichoscopy patterns using nonpolarized (contact) and polarized (noncontact) dermatoscopy in hair and shaft disorders. Int J Trichology. 2014;6:54–62. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.138588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodney IJ, Onwudiwe OC, Callender VD, Halder RM. Hair and scalp disorders in ethnic populations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salam A, Aryiku S, Dadzie OE. Hair and scalp disorders in women of African descent: an overview. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169((suppl 3)):19–32. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franbourg A, Hallegot P, Baltenneck F, Toutain C, Leroy F. Current research on ethnic hair. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48((suppl)):S115–S119. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semble AL, McMichael AJ. Hair loss in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015;34:81–88. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2015.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Syed A, Kuhajda A, Ayoub H, et al. African-American hair: its physical properties and differences relative to Caucasian hair. Cosmet Toil. 1995;110:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franbourg A, Hallegot P, Baltenneck F, Toutain C, Leroy F. Current research on ethnic hair. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48((suppl 6)):S115–S119. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malakar S, Trichoscopy . New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2017. A Text and Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tosti A. ed 2. Boca Raton, Taylor & Francis Group; 2016. Dermoscopy of the Hair and Nails. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A. ed 1. London: Springer; 2012. Atlas of Trichoscopy: Dermoscopy in Hair and Scalp Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraham LS, Piñeiro-Maceira J, Duque-Estrada B, Barcaui CB, Sodré CT. Pinpoint white dots in the scalp: dermoscopic and histopathologic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:721–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kossard S, Zagarella S. Spotted cicatricial alopecia in dark skin. A dermoscopic clue to fibrous tracts. Australas J Dermatol. 1993;34:49–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1993.tb00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ardigò M, Torres F, Abraham LS, Piñeiro-Maceira J, Cameli N, Berardesca E, Tosti A. Reflectance confocal microscopy can differentiate dermoscopic white dots of the scalp between sweat gland ducts or follicular infundibulum. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1122–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sperling LC. Hair density in African Americans. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:656–658. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinn CR, Quinn TM, Kelly AP. Hair care practices in African American women. Cutis. 2003;72:280–282. 285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres F. Androgenetic, diffuse and senescent alopecia in men: practical evaluation and management. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;47:33–44. doi: 10.1159/000369403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inui S, Nakajima T, Itami S. Scalp dermoscopy of androgenetic alopecia in Asian people. J Dermatol. 2009;36:82–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiramel MJ, Sharma VK, Khandpur S, Sreenivas V. Relevance of trichoscopy in the differential diagnosis of alopecia: a cross-sectional study from North India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:651–658. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.183636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaliyadan F, Nambiar A, Vijayaraghavan S. Androgenetic alopecia: an update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:613–625. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.116730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhamla SA, Dhurat RS, Saraogi PP. Is trichoscopy a reliable tool to diagnose early female pattern hair loss? Int J Trichology. 2013;5:121–125. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.125603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Moura LH, Duque-Estrada B, Abraham LS, Barcaui CB, Sodré CT. Dermoscopy findings of alopecia areata in an African-American patient. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2008;2:52–54. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2008.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kibar M, Aktan Ş, Lebe B, Bilgin M. Trichoscopic findings in alopecia areata and their relation to disease activity, severity and clinical subtype in Turkish patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:e1–e6. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bapu NG, Chandrashekar L, Munisamy M, Thappa DM, Mohanan S. Dermoscopic findings of alopecia areata in dark skinned individuals: an analysis of 116 cases. Int J Trichology. 2014;6:156–159. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.142853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mane M, Nath AK, Thappa DM. Utility of dermoscopy in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:407–411. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guttikonda AS, Aruna C, Ramamurthy DV, Sridevi K, Alagappan SK. Evaluation of clinical significance of dermoscopy in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:628–633. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.193668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes R, Chiaverini C, Bahadoran P, Lacour JP. Corkscrew hair: a new dermoscopic sign for diagnosis of tinea capitis in black children. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:355–356. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42((pt 1)):1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90001-x. quiz 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vazquez-Lopez F, Palacios-Garcia L, Argenziano G. Dermoscopic corkscrew hairs dissolve after successful therapy of Trichophyton violaceum tinea capitis: a case report. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:118–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2011.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinheiro AM, Lobato LA, Varella TC. Dermoscopy findings in tinea capitis: case report and literature review. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:313–314. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brasileiro A, Campos S, Cabete J, Galhardas C, Lencastre A, Serrão V. Trichoscopy as an additional tool for the differential diagnosis of tinea capitis: a prospective clinical study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:208–209. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amer M, Helmy A, Amer A. Trichoscopy as a useful method to differentiate tinea capitis from alopecia areata in children at Zagazig University Hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:116–120. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slowinska M, Rudnicka L, Schwartz RA, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Rakowska A, Sicinska J, Lukomska M, Olszewska M, Szymanska E. Comma hairs: a dermatoscopic marker for tinea capitis: a rapid diagnostic method. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59((suppl)):S77–S79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ekiz O, Sen BB, Rifaioğlu EN, Balta I. Trichoscopy in paediatric patients with tinea capitis: a useful method to differentiate from alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1255–1258. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ankad BS, Naidu MV, Beergouder SL, Sujana L. Trichoscopy in trichotillomania: a useful diagnostic tool. Int J Trichology. 2014;6:160–163. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.142856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinto AC, Andrade TC, Brito FF, Silva GV, Cavalcante ML, Martelli AC. Trichotillomania: a case report with clinical and dermatoscopic differential diagnosis with alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:118–120. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jain N, Doshi B, Khopkar U. Trichoscopy in alopecias: diagnosis simplified. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:170–178. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.130385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindsey SF, Tosti A. Ethnic hair disorders. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;47:139–149. doi: 10.1159/000369414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chicarilli ZN. Follicular occlusion triad: hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;18:230–237. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198703000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koca R, Altinyazar HC, Ozen OI, Tekin NS. Dissecting cellulitis in a white male: response to isotretinoin. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:509–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01552_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMichael AJ. Hair and scalp disorders in ethnic populations. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:629–644. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scott DA. Disorders of the hair and scalp in blacks. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:387–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benvenuto ME, Rebora A. Fluctuant nodules and alopecia of the scalp. Perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1115–1117, 1118–1119. doi: 10.1001/archderm.128.8.1115b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tosti A, Torres F, Miteva M. Dermoscopy of early dissecting cellulitis of the scalp simulates alopecia areata (in English, Spanish) Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:92–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slepyan AH. Traction alopecia. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;78:395–398. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1958.01560090111025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khumalo NP, Jessop S, Gumedze F, Ehrlich R. Determinants of marginal traction alopecia in African girls and women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samrao A, Price VH, Zedek D, Mirmirani P. The “fringe sign” - a useful clinical finding in traction alopecia of the marginal hair line. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rollins TG. Traction folliculitis with hair casts and alopecia. Am J Dis Child. 1961;101:639–640. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1961.04020060097013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fox GN, Stausmire JM, Mehregan DR. Traction folliculitis: an underreported entity. Cutis. 2007;79:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tosti A, Miteva M, Torres F, Vincenzi C, Romanelli P. Hair casts are a dermoscopic clue for the diagnosis of traction alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1353–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olsen EA, Callender V, Sperling L, McMichael A, Anstrom KJ, Bergfeld W, Durden F, Roberts J, Shapiro J, Whiting DA. Central scalp alopecia photographic scale in African American women. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:264–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.LoPresti P, Papa CM, Kligman AM. Hot comb alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 1968;98:234–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khumalo NP, Gumedze F. Traction: risk factor or coincidence in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia? Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1191–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blattner C, Polley DC, Ferritto F, Elston DM. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:50–51. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.105484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miteva M, Tosti A. Dermatoscopic features of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miteva M, Tosti A. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia presenting with irregular patchy alopecia on the lateral and posterior scalp. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:1–5. doi: 10.1159/000370315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herskovitz I, Miteva M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:175–181. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S100816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ankad BS, Beergouder SL, Moodalgiri VM. Lichen planopilaris versus discoid lupus erythematosus: a trichoscopic perspective. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:204–207. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.130409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mardones F, Shapiro J. Lichen planopilaris in a Latin American (Chilean) population: demographics, clinical profile and treatment experience. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:755–759. doi: 10.1111/ced.13203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tosti A, Ross EK, Patterns of scalp and hair disease revealed by videodermoscopy . Dermoscopy of Hair and Scalp Disorders. In: Tosti A, editor. ed 1. London: Informa Healthcare; 2007. pp. pp 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duque-Estrada B, Tamler C, Sodré CT, Barcaui CB, Pereira FB. Dermoscopy patterns of cicatricial alopecia resulting from discoid lupus erythematosus and lichen planopilaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:179–183. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dlova NC, Jordaan HF, Skenjane A, Khoza N, Tosti A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical review of 20 black patients from South Africa. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:939–941. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miteva M, Whiting D, Harries M, Bernardes A, Tosti A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in black patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:208–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: a frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pirmez R, Donati A, Valente NS, Sodré CT, Tosti A. Glabellar red dots in frontal fibrosing alopecia: a further clinical sign of vellus follicle involvement. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:745–746. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abbas O, Chedraoui A, Ghosn S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting with components of Piccardi-Lassueur-Graham-Little syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57((suppl)):S15–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, Valente NS, Romiti R. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424–1427. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Barreto T, Quintella DC, Cuzzi T. Successful treatment of facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia with oral isotretinoin. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:111–113. doi: 10.1159/000464334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:439–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ocampo-Garza J, Herz-Ruelas ME, Ocampo-Candiani J. Acquired hyperpigmentation and cicatricial alopecia. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352:227–228. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rao R, Sarda A, Khanna R, Balachandran C. Coexistence of frontal fibrosing alopecia with lichen planus pigmentosus. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:622–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, Campos-do-Carmo G, Valente NS, Romiti R, Sodré CT, Tosti A. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1387–1390. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Callender VD, Reid SD, Obayan O, Mcclellan L, Sperling L. Diagnostic clues to frontal fibrosing alopecia in patients of African descent. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:45–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sonthalia S, Jha AK, Tiwary PK. A dermoscopic diagnosis and activity evaluation of frontal fibrosing alopecia in an Indian lady. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:162–163. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_307_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lanuti E, Miteva M, Romanelli P, Tosti A. Trichoscopy and histopathology of follicular keratotic plugs in scalp discoid lupus erythematosus. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:36–38. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.96087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thakur BK, Verma S, Raphael V. Clinical, trichoscopic, and histopathological features of primary cicatricial alopecias: a retrospective observational study at a tertiary care centre of North East India. Int J Trichology. 2015;7:107–112. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.167459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Abedini R, Kamyab Hesari K, Daneshpazhooh M, Ansari MS, Tohidinik HR, Ansari M. Validity of trichoscopy in the diagnosis of primary cicatricial alopecias. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1106–1114. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483–489. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S99225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kelly AP. Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:645–653. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fabris MR, Melo CP, Melo DF. Folliculitis decalvans: the use of dermatoscopy as an auxiliary tool in clinical diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:814–816. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Khumalo NP, Dawber RP, Ferguson DJ. Apparent fragility of African hair is unrelated to the cystine-rich protein distribution: a cytochemical electron microscopic study. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:311–314. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Quaresma MV, Martinez Velasco MA, Tosti A. Dermoscopic diagnosis of hair breakage caused by styling procedures in patients of African descent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72((suppl)):S39–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Miyamoto M, Tsuboi R, Oh-I T. Case of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa: scanning electron microscopic observation. J Dermatol. 2009;36:109–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chernosky ME, Owens DW. Trichorrhexis nodosa. Clinical and investigative studies. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:577–585. doi: 10.1001/archderm.94.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burkhart CG, Burkhart CN. Trichorrhexis nodosa revisited. Skinmed. 2007;6:57–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.06044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]