Abstract

Autoimmune hepatitis affects patients of all ages and gender, across all geographic regions. Although still rare, its incidence and prevalence are increasing. Genetic predisposition conveyed by human leucocyte antigen is a strong risk factor for the disease and may be responsible in part for the wide variation in presentation in different geographic regions. Our understanding of the underlying pathogenic mechanisms is evolving and may lead to development of more targeted immunotherapies. Diagnosis is based on elevated levels of serum aminotransferases, gamma globulins, autoantibodies and characteristic findings on histology. Exclusion of other causes of chronic hepatitis is important. Although undiagnosed disease is associated with poor outcomes, it is readily treatable with timely immunosuppressive therapy in the majority of patients. International guidelines are available to guide management but there exists a disparity in the standard treatment regimens. This minireview aims to review the available guidelines and summarize the key recommendations involved in management of this complex autoimmune disease.

Keywords: Autoimmune hepatitis, Treatment, Hypergammaglobulinemia, Autoantibodies, Azathioprine

Core tip: Autoimmune hepatitis, is a rare inflammatory condition of the liver that can affect all ages and gender, across all geographic regions. It has a wide variability in clinical presentation and thus, diagnosis can be challenging. While undiagnosed disease leads to significant morbidity and mortality, timely initiation of treatment leads to favorable outcomes in the majority of cases. Guidelines are available by international societies but there exists a disparity in the standard treatment indications and regimens. In this minireview, we summarize key points from the available literature and guidelines, focusing on appropriate indications and different treatment regimens available.

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the liver of unknown cause that can affect children and adults of all ages. The course of the disease can occasionally be fluctuating, but is generally progressive. It is marked by interface hepatitis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration on histology, serum hypergammaglobulinemia and characteristic circulating autoantibodies. Since it was first described by Waldenström in 1950 as a disease affecting young women characterized by jaundice, high serum gammaglobulins, and amenorrhea causing liver cirrhosis, it has been known by many different labels including “lupoid” hepatitis, but AIH has been accepted as the most appropriate term[1].

Many variant, overlapping forms of AIH exist, particularly with coexisting cholestatic features, primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Diagnosis requires exclusion of other causes of chronic hepatitis such as drug induced liver injury (DILI), viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) as some of these cases respond to immunosuppressive therapy. A therapeutic response to corticosteroids in AIH was observed in the early 1950s, as well as an early relapse after withdrawal of corticosteroids[2]. By the late 1950s, combined approach with immunomodulators was described and it remains the cornerstone of therapy. Wide heterogeneity of clinical presentation and relatively rare incidence of the disease has limited the advancement in clinical trials. Thus, more than 50 years after its original description, AIH remains a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

Guidelines by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) (2010) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) (2015) provide practice guidance on the management of this complex disease[3,4]. The aim of this minireview is to provide an overview of the current treatment guidelines, with an emphasis on appropriate immunosuppressive therapy and difficult to manage cases.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

AIH is a disease that affects all age groups, occurs in all ethnicities and geographic regions but affects the female gender disproportionately. In the United States, women are affected 3.5 times more than men, and 76% of patients in a Swedish study were women[5,6].

Previously considered to be a disease of the young, a recent large Danish nationwide population-based study demonstrated the peak age of incidence at more than 60 years for both men and women. It also showed that both the incidence and prevalence of AIH is rising[7]. Although it is still considered a rare disease, as its prevalence ranges from 16 to 18 cases per 100000 persons in Europe. In Europe and the United States, it accounts for 2% to 3% of the pediatric and 4% to 6% of the adult liver transplantations[3].

The occurrence and clinical course appear to vary according to ethnicity. The disease appears to be more common and more severe in the North American aboriginals compared to the Caucasian population; African-Americans are more likely to present with cirrhosis; patients with Asian or other non-European Caucasoid back ground have poor outcomes. These diverse clinical outcomes between different ethnic groups, within and between countries may reflect differences in genetic predisposition, environmental stimuli as well as complex socioeconomic reasons such as delivery of healthcare[8].

PATHOGENESIS

The model for the pathogenesis of AIH follows the general hypothesis underlying many autoimmune diseases. The disease is thought to arise in a genetically predisposed individual when a potential environmental antigenic trigger sets of a T-cell mediated immune response directed at liver antigens, leading to a progressive inflammatory process and scarring[9].

Although a definite antigenic trigger has not been found, some of the proposed triggering factors include drugs, toxins and infectious agents. Genetic predisposition to AIH is primarily conveyed by human leucocyte antigen (HLA) haplotype which determines the autoantigen presentation and CD4+ helper T-cell recognition. HLA-DR3 was shown to be strongly associated with the onset of AIH in the Caucasian population. Subsequently characterized as HLA DRB1*0301, it is associated with a younger age of onset and a more severe phenotype. This HLA class II locus determines the shape of the peptide binding groove of the Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II complex which presents peptide antigens to the CD4+ T cells. Strong association of DRB1*0301 haplotype with AIH suggests that a specific peptide bound to this complex is recognized by T cells within the liver which then become autoreactive[10].

Various other haplotypes have been found to be associated with AIH in different geographic populations such as DRB1*0401 in Europeans and DRB1*0405 in Japanese[10]. When negative for DRB1*0301, these patients demonstrate a milder form of the disease with older age of onset. Association with varying haplotypes suggests diversity among the peptide antigens triggering the disease but provide a stronger evidence for a T-cell mediated immune reaction driving inflammation and fibrosis.

HLA haplotypes convey the strongest genetic predisposition to AIH. In addition, many other genetic risk factors have been identified, predominantly affecting the immune regulatory function. Particular variant of cytotoxic lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4)[11], important co-stimulator of T-cells has been associated with AIH. Mutations in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene, important for inducing central immune tolerance, leads to a complex autoimmune phenotype, with majority developing AIH.

Knowledge of the underlying genetic predisposition may lead to identification of potential environmental triggers, better understanding of the disease phenotype and development of therapeutic targets in the future, but this as of now appears to be clinically dispensable.

CLINICAL FEATURES

AIH is a heterogenous disease, characterized by a fluctuating course of activity. Therefore, the clinical manifestations are variable. The spectrum of presentation ranges from asymptomatic disease to acute severe hepatitis or debilitating smoldering cirrhosis. Thus, the diagnosis of AIH should be entertained in any patient presenting with signs or symptoms liver disease, whether acute or chronic.

Presentation

Up to a third of adult patients are found to have acute icteric hepatitis[12]. Presentation is similar to acute viral hepatitis and patients may develop non-specific symptoms such as malaise, fatigue, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, and arthralgias. Physical exam may be normal or reveal jaundice, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. Occasionally, patients may have a severe or fulminant presentation with elevated prothrombin time and serum aminotransferase levels in thousands leading to acute liver failure and need for liver transplantation. This presentation is more common in children and relatively rare after 30 years of age.

Many patients with an acute presentation can undergo spontaneous recovery and the initial episode misdiagnosed as a transient illness. Subclinical disease can progress and lead to cirrhosis. Approximately, one third of all adult patients and almost 50% of children already have cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis[13,14]. AIH, can therefore, present for the first time with signs and symptoms of decompensated cirrhosis including ascites, variceal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy.

Due to the improvement in diagnostic modalities, more than half of all patients diagnosed with AIH have no specific symptoms. They are usually diagnosed upon work up of abnormal liver enzymes detected on routine blood work for other indications. AIH may rarely be diagnosed during pregnancy, or manifest for the first time during post-partum period. Patients with AIH can undergo spontaneous remissions during pregnancy and typically experience flare up in the immediate post-partum period, likely due to immune reconstitution[15].

It is important to keep in mind the concomitant occurrence of other autoimmune diseases with AIH, particularly autoimmune thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, type 1 Diabetes mellitus and celiac disease[16].

Laboratory features

Abnormalities of the liver biochemistry predominantly reflect a hepatocellular pattern with elevated aminotransferases and variable, but usually mild elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase. Any magnitude of serum aminotransferase elevation is possible, and higher elevations are associated with a more severe course and poor outcomes[17].

Generalized elevation of serum gammaglobulins, particularly the IgG fraction is a characteristic feature of AIH. It can be seen in up to 90% of patients with AIH and a diagnosis of AIH should be questioned in patients without hypergammaglobulinemia[18,19].

Autoantibodies

Presence of serum auto-antibodies is a characteristic hallmark of AIH and serological testing is an important part of the diagnostic work up of the disease[1,18]. Antibodies important for the diagnosis of AIH are described in Table 1. Diagnostic value of serological testing also depends on the technique used. Performance parameters for indirect immunofluorescence assays are well defined for diagnosis of AIH and this is the recommended technique for antibody detection[19].

Table 1.

Serologic markers of autoimmune hepatitis

| ANA | Variably expressed with ASMA in type 1 AIH |

| Heterogenous antigen profile | |

| No single staining pattern is pathognomonic for diagnosis of AIH | |

| Most useful when found with ASMA (diagnostic accuracy 74%)[20] | |

| ASMA | Marker of type 1 AIH along with ANA |

| Reacts to several cytoskeletal elements, especially F-actin. | |

| ELISA against F-actin as the substrate can be used instead of indirect immunofluorescence but may miss the diagnosis in 15% to 20% of cases[20] | |

| Anti-SLA/LP | Only disease specific antibody with specificity of 99% for AIH |

| Present in only 15% patients with AIH in the United States | |

| Known to have a defined antigen, SEPSECS. ELISA is the preferred methodology of testing | |

| Closely associated with HLA DRB1*03 and Anti-Ro/SSA | |

| Have prognostic value as it is associated with severe disease, higher risk of relapse and need for lifelong treatment | |

| Anti-LKM1 | Serologic marker for type 2 AIH. |

| CYP2D6 is the target antigen. Shares homology with hepatitis C virus antigen | |

| Present mainly in children, worldwide. Rare in adults in the United States (< 4%) | |

| Associated with HLA DRB*07 | |

| Atypical pANCA | Common in type 1 AIH, and absent in type 2 AIH |

| Associated with PSC, UC |

ANA: Antinuclear antibodies; ASMA: Anti-smooth muscle antibodies; AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; ELISA: Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; Anti-SLA/LP: Anti-soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas antibody; SEPSECSA: Sep (phosphoserine) tRNA: Sec (selenocysteine) tRNA synthase; Ro/SSA: Ribonucleoprotein/Sjögren’s syndrome A protein; Anti-LKM1: Antibodies to liver kidney microsome type 1; pANCA: Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

This is performed using rodent tissue or Hep2 cell lines and results are given in titers. It provides the best sensitivity and specificity profile for antinuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA). However, it is labor and time intensive, subject to intra-observer variation and requires experienced lab technicians. Therefore, solid phase enzyme immunoassays have gained popularity and are replacing indirect immunofluorescence. These tests are very antigen specific, easy to perform and give rapid results. However, diagnostic parameters for ANA, ASMA detected by enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay (ELISA) are not well defined and as the recombinant antigens may differ from those detected by indirect immunofluorescence, the results of the two assays should not be equated[20].

Several other antibodies have been evaluated such as antibodies to asialoglycoprotein receptor which are closely associated with histologic activity and may prove useful in defining the treatment endpoint. Antibodies to liver cytosol type 1 can coexist with anti LKM1 in type 2 AIH and are associated with early age of disease onset and severe phenotype. Newer antibodies continue to be characterized to improve the diagnostic accuracy and prognostic value[21].

Histology

Histological confirmation is a prerequisite for diagnosis of AIH[1,18]. It is also useful in guiding therapeutic decisions. Certain characteristic features have been described but none are pathognomonic. Interface hepatitis characterized by inflammation at the parenchymal portal junction is the hallmark feature. Hepatocyte rosette formation, dense plasma cell rich infiltrate and emperiopolesis (active penetration of lymphocytes into hepatocytes) are other common findings. Multi acinar and bridging necrosis is associated with severe disease[22].

DIAGNOSIS AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

In patients presenting with signs and symptoms of acute or chronic hepatitis, diagnosis of AIH is made on the basis of aforementioned biochemical and serological lab results, and confirmed by liver histology. Difficulties may arise due to the wide variability of presentation, fluctuating disease course, variant forms and presence of co-existing liver diseases. Therefore prior to confirming AIH, it is crucial to exclude other causes of inflammatory hepatitis such as alcoholic or NASH, viral hepatitis and DILI. Other causes of chronic liver disease such Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis and alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency should be ruled out as well.

Different scoring systems have been proposed to assist in the diagnosis of AIH. In 1999, the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) published a comprehensive scoring system which grades every clinical, laboratory and histological feature of AIH, including response to corticosteroid treatment. Initially designed as a research tool for clinical trials, it was useful in clinical practice for patients with few or atypical features of disease. Its complexity and failure to distinguish AIH from cholestatic syndromes limited the clinical utility[1]. In 2008, a simplified scoring system was proposed by the same group for every day clinical practice (Table 2) [18]. It considers the key diagnostic criteria (autoantibodies, degree of hypergammaglobulinemia, liver histology and exclusion of viral hepatitis). It performs well with good sensitivity and specificity (both more than 90%) in diverse populations, and with chronic disease. Its relative ease of use makes it friendly for clinical practice. However, this has not been validated in prospective clinical trials and its utility in acute or fulminant presentations is limited.

Table 2.

Simplified diagnostic criteria of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group

| Parameter | Discriminator | Score |

| ANA or ASMA | ≥ 1:40 | + 11 |

| ≥ 1:80 | + 21 | |

| Anti-LKM | ≥ 1:40 | + 21 |

| Anti-SLA/LP | Any titer | + 21 |

| Total IgG | > ULN | + 1 |

| > 1.1 × ULN | + 2 | |

| Liver histology | Compatible with AIH | + 1 |

| Typical of AIH | + 2 | |

| Absence of viral hepatitis | No | 0 |

| Yes | + 2 |

Addition of all points for autoantibodies must be done, maximum 2 points allowed. Definite autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) ≥ 7; Probably ≥ 6. Typical histology for AIH: Each of the following should be present, interface hepatitis, plasma cell infiltrates, emperiopolesis, and hepatic rosette formation. Compatible liver histology: Chronic hepatitis with lymphocytic infiltrations without typical features as above. AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; ANA: Antinuclear antibody; ASMA: Anti-smooth muscle antibody; Anti-LKM: Anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody; Anti-SLA/LP: Anti-soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas antibody[18].

Scoring systems are not particularly helpful in making the distinction from DILI during acute or hyperacute presentation. Some drugs, such as minocycline and nitrofurantoin, can induce a drug induced autoimmune-like hepatitis and appropriate diagnosis can only be made with passage of time[23]. In severe presentations, steroids should be started and the most likely offending drug should be withdrawn. After normalization of biochemical parameters, steroids should be tapered. De novo AIH will typically recur after treatment withdrawal whereas DILI often resolves with the removal of offending agent and does not recur.

TREATMENT

All patients with AIH must be considered candidates for treatment and the timing of therapy rather than the need for therapy is the most important variable to consider. Early studies in 1970s and 1980s showed that untreated patients with moderate to severe AIH, had very poor outcomes, and the 6-month mortality reached as high as 40%. It was also shown that patients treated with immunosuppressive therapy did very well with improvement in biochemical parameters, clinical symptoms and overall mortality[17,24,25].

Liver biopsy should be performed in all patients to make a diagnosis of AIH and before starting treatment. Transjugular liver biopsy may be performed if there is severe coagulopathy. There is general consensus that patients with active AIH [these include patients with aspartate transaminase (AST) > 10 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), AST > 5 × ULN and total IgG > 2 × ULN, or with hepatic activity index > 4/18 on histology] need timely initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. As per the AASLD guidelines, absolute indications for treatment are (1) AST > 10 × ULN; (2) AST > 5 × ULN along serum IgG > 2 × ULN; (3) bridging necrosis or multiacinar necrosis on histology; and (4) incapacitating symptoms such as fatigue and arthralgia[3]. The EASL clinical practice guidelines consensus group recommends treatment for all patients with active AIH[4]. Our recommendation based on review of the literature and clinical guidelines is that all patients with clinical, laboratory or histological features of active liver inflammation should be considered as candidates for treatment as long as they do not have contraindications or risks for significant adverse effects from corticosteroid or azathioprine therapy. Patients with advanced fibrosis and even cirrhosis with active ongoing inflammation on histology should receive therapy as regression of scarring with successful treatment has been reported[17,24,25]. Acute presentation with jaundice as well as subclinical development of fibrosis is more common in childhood, such that more than 50% of the children diagnosed with AIH already have cirrhosis[26]. Therefore, most children with AIH need to be started on treatment. Risks of therapy outweigh any benefits when cirrhosis is already decompensated or there is minimal or no disease activity on histology. Therapy should not be started in such patients.

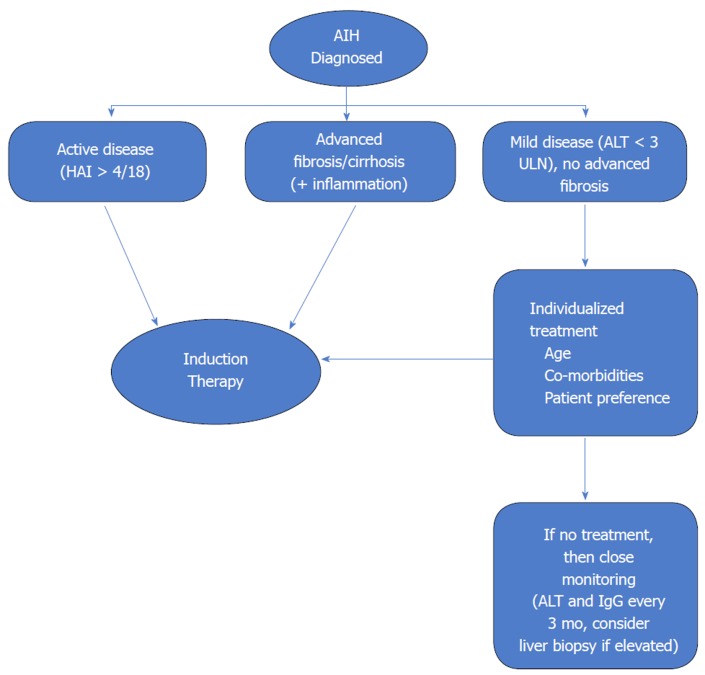

Benefits of treatment in asymptomatic older individuals without cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis and mild disease activity are unclear. Treatment in such cases must be individualized. The risks of immunosuppression must be weighed against the risk of progression of subclinical disease. Ten-year survival in patients with mild disease without treatment has been reported to range from 67% to 90%[27]. Therefore, the urgency of initiation of treatment is much less in such a patient population. However, AIH can have a fluctuating course with spontaneous remissions and relapses. A significant proportion of asymptomatic patients become symptomatic over time and risk for progression to cirrhosis and HCC is possible. Therefore, the guidelines agree that treatment should be offered to patients with mild disease especially if they do not have contraindications to immunosuppressive therapy. If decision is made to withhold treatment then these patients should be closely monitored with measurement of ALT and total IgG every 3 mo[3,4]. An algorithm for decision making regarding initiation of immunosuppressive therapy is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for decision making regarding initiation of induction immunosuppressive therapy. Patients with active disease and advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis need initiation of therapy. Patients with mild or asymptomatic disease need an individualized approach. Patients with cirrhosis who have decompensated disease or no inflammatory activity on histology do no benefit from treatment. AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; ULN: Upper limit of normal; HAI: Hepatic activity index[4].

Induction of remission

The goal of treatment is to obtain complete biochemical and histological resolution of disease. Two treatment regimens are equally effective and are recommended by the AASLD and British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG). First is prednisone monotherapy starting at 60 mg daily, tapered down over 4 wk to 20 mg daily which is then continued until treatment end point. Dose can subsequently be tapered by 5 or 2.5 mg per week to achieve the lowest effective dose of steroids. The BSG, on the other hand, recommends treatment in all cases where the serum aminotransferases are greater than 5 times the ULN, irrespective of the other criteria for treatment[28]. The other is the combination regimen of prednisone starting at 30 mg daily tapered over 4 wk to 10 mg daily and azathioprine 50 mg daily (United States) or 1-2 mg/kg per day (Europe)[3,28].

The evidence for mortality benefit of immunosuppressive therapy with steroids and/or combination with azathioprine was established in a number of controlled trials in the 1960s and 1970s. A sentinel study performed in Mayo clinic in 1972 compared prednisone monotherapy (starting with 60 mg/d, tapered down to 20 mg over four weeks), azathioprine monotherapy (100 mg/d), combination therapy (prednisone starting at 30 mg/d, decreased to 10 mg/d maintenance after 4 wk combined with azathioprine at 50 mg/d) and placebo. There was a significant but similar mortality benefit with prednisone monotherapy and combination therapy when compared to placebo (6 % vs 7% vs 41 %). The combination regimen, however, was associated with fewer side effects (10% vs 44%). Seventy-five percent of the patients achieved histological remission, several months after clinical and biochemical remission[17]. This, along with other trials at the time, demonstrated high mortality with azathioprine monotherapy when used for remission induction, likely due to slow onset of action and this was discarded as a valid option.

Thus, the combination regimen was shown to have the best therapeutic profile, and is universally recommended as the first line option[3,4,28].

Upfront combination therapy is especially useful in patients with uncontrolled hypertension, brittle diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, emotional liability or morbid obesity who are unlikely to tolerate higher doses of steroids well. Similarly, addition of azathioprine may not be appropriate for patients with severe cytopenias, underlying malignancy, pregnancy or established deficiency of thiopurine methyltransferase enzyme (TPMT). Therefore, it is important to individualize regimens based on patient factors and co-morbidities.

Prednisolone is the preferred steroid used in Europe, in contrast to prednisone in the United States, as it does not require intrahepatic conversion to the active form. It also achieves quicker peak plasma concentrations and has greater systemic bioavailability compared to prednisone. Although there does not appear to be a difference in outcomes, it makes sense to use prednisolone in the acute fulminant variant of AIH.

In addition to the classical regimen recommended by the AASLD and BSG, several modifications have been proposed and are being used in clinical practice. A recent questionnaire study by IAIHG evaluated the real-world management of AIH and it suggested wide variations in the initial doses of standard induction therapy and steroid tapering protocols among expert centers[29]. As a general principle, higher the initial steroid dose, faster is the biochemical response with a slightly increased but transient risk of steroid related side effects. Faster induction overall reduces the time to tapering of steroids and thus limiting overall duration of steroid related side effects. In a German cohort, dose of predniso(lo)ne (up to 1 mg/kg per day) in combination with azathioprine lead to more rapid normalization of the transaminases[30]. A retrospective analysis from Turkey showed a faster biochemical response, less relapses and better survival over 12 mo with starting prednisolone dose of 40 mg and slow taper over 9 weeks in combination with azathioprine in comparison to the standard combination regimen recommended by AASLD[31]. As absence of an early biochemical response is a negative prognostic indicator, strategy to use the most effective dose of steroids for the patient and guide further management based on response is most prudent.

Rate of therapeutic response and dose limiting side effects typically influence the tapering schedule of steroids. Initiation of azathioprine maintenance therapy as soon as possible can help achieve reduction of steroid dose faster. However, in contrast to the AASLD recommendations, and as suggested in the EASL guidelines, it seems reasonable to delay the introduction of azathioprine until early biochemical response is seen from steroid use (usually 2 wk) as that can help clarify diagnostic uncertainties, and differentiate between primary non-response and azathioprine induced hepatotoxicity (although rare, its frequency is increased in advanced liver disease).

It is important to counsel patients about steroid and azathioprine related side-effects. Appropriate adjunctive therapies such as vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent bone loss should be given. Vaccination against hepatitis A and B should be completed.

Budesonide, an oral steroid, with a very high first pass metabolism, has been shown in a large, double blind randomized clinical trial to be an effective alternative therapy for AIH[32]. Dose is started at 9 mg daily (3 pills of 3 mg each) in combination with standard azathioprine regimen until remission is induced. A high first pass metabolism leads to less dose limiting side effects when compared to prednisone (28% vs 53%). However, this is negated in patients with cirrhosis who may have unpredictable systemic levels due to porto-systemic shunting. Also, the rate of remission induced by budesonide in the study was lower compared to appropriately dosed prednisone[30]. Data regarding the long-term use of budesonide is currently lacking. Therefore, there is a role of budesonide in management of non-cirrhotic patients with AIH who are unable to tolerate systemic side effects of steroids but it is not appropriate for the majority of the patients as a first line agent.

Maintenance therapy

Azathioprine is the drug of choice for maintenance therapy of AIH, as it has been shown to maintain remission effectively in up to 90% patients with fewer side effects compared to low-dose steroid therapy[25,33]. Target dose is usually 1 to 2 mg/kg, but can be titrated up to 2 mg/kg to decrease risk of relapse after steroid withdrawal. To test the tolerance of the drug, it is recommended to start at a lower dose, usually 50 mg daily. Patients should be counseled about the side effects of the drug which include risk of bone marrow suppression, rare risk of malignancy, small risk of drug induced hepatoxicity and pancreatitis. In addition, up to 5% patients demonstrate intolerance to azathioprine manifested by abdominal discomfort, malaise, nausea and fever. Symptoms usually dissipate within 2 to 3 d of stopping the drug. Azathioprine is a category D drug for teratogenic risk, however, all reports from patients treated during pregnancy suggest that it is safe. The risk for maternal and fetal mortality from a disease flare up during pregnancy outweighs any potential harms from the drug, therefore it should be continued at the lowest effective dose to maintain remission during pregnancy.

TPMT is one of the enzymes that is involved in azathioprine metabolism. Patients with genetically determined TPMT deficiency (present in up to 2% of the general population) may be at a higher risk for severe bone marrow suppression. EASL guidelines recommend that when available, serum TPMT testing be performed prior to initiation of azathioprine in patients with AIH. However, not all patients with low levels of TPMT develop bone marrow toxicity and screening for blood TPMT activity has not reduced the frequency of azathioprine related side effects compared with unscreened patients with AIH[34,35]. Therefore, a more pragmatic approach appears to be the initiation of the drug at low dose (50 mg daily) and close monitoring of complete blood count (CBC) (every 2 wk) in the first few months of therapy.

In the first three months of therapy, monitoring of blood counts is done every 2 wk after which it can be spread out. Dose of predniso(lo)ne is tapered in parallel down to 10 mg daily until normalization of transaminases and IgG occurs. Subsequently, steroids can be tapered slowly (in steps of 2.5 to 5 mg daily) every 4 to 12 wk. Transaminases should be closely monitored during this time to detect reactivation of the disease which can be controlled by a transient increase in the steroid dose. Rarely, azathioprine related hepatotoxicity can occur. Usually, IgG levels remain normal in this case and can help differentiate with insufficient treatment response, insufficient dose or lack of compliance. There may be a role of checking thiopurine metabolites (6 thioguanine, 6 methylmercaptopurine) as low levels may indicate lack of compliance. Liver biopsy can help when differentiation between reactivation of AIH or azathioprine related hepatoxicity remains unclear.

Patients who are intolerant to azathioprine, have several alternative modalities for maintenance. 6-mercaptopurine, the active metabolite of azathioprine, can be used in up to 50% of the patients intolerant to azathioprine. However, this should not be tried in patients have had pancreatitis, hepatotoxicity or severe bone marrow suppression secondary to azathioprine.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) has been established as an effective second line agent for AIH[35,36]. It appears to be more useful for patients who suffer from azathioprine intolerance rather than treatment failure with azathioprine. It is tolerated very well and at a target dose of 2 g/d, it can maintain a stable remission rate around 70%[37]. It has been reported to have teratogenic properties and should be prescribed to women of childbearing age with due precaution. Lastly, for patients with mild disease and good tolerance to steroids, chronic low dose predniso(lo)ne at 10 mg daily or less is a viable option to maintain remission.

With good compliance and standard treatment regimens, majority of the patients achieve and maintain sustained remission. 10-year life expectancy for patients with and without cirrhosis and AIH is 89% and 90% respectively, in tertiary referral centers. Overall 10-year survival rate of 93% approaches that of age matched cohorts of the general population[38].

Treatment withdrawal

Most patients with AIH will need lifelong maintenance therapy. This is because only 20% of patients with AIH can maintain a sustained remission after withdrawal of all immunosuppressive therapy[39]. However, this does not preclude a consideration of trial of treatment withdrawal in appropriate candidates. Treatment should be continued for at least 2 years after complete biochemical remission (normal transaminases and normal total IgG) has been achieved. This is because histological resolution lags behind biochemical remission. Patients with persistent mild elevation of transaminases and/or IgG, or intermittent flares during maintenance therapy are likely to experience disease relapse, and treatment withdrawal should not be attempted in them. A recent study showed that patients with ALT levels less than half the ULN and IgG levels in the lower range of normal (< 12 g/L) were much more likely to maintain sustained remission of medications[40]. Liver biopsy can be helpful in excluding a trial of withdrawal as mild ongoing inflammation [hepatic activity index (HAI) > 3] is a strong predictor of relapse. However, a normal liver biopsy is a poor predictor of the probability of relapse. When a decision is made to attempt treatment withdrawal, azathioprine is slowly decreased with careful monitoring of transaminases. Patients who have been successfully weaned off medical therapy should be monitored at regular intervals as up to 50% suffer a relapse within 6 mo, most within 2 years but relapses decades after remission have also been described. Treatment with the initial induction regimen usually helps to get the disease under control. Patients who undergo repeated relapse have higher incidence of cirrhosis, death from liver failure, higher rate of drug induced side effects and overall adverse outcomes[41]. Therefore, lifelong maintenance therapy is needed in patients who suffer a relapse.

Difficult to treat patients: Incomplete and non-responders

Most patients respond well to standard immunosuppressive regimen and at least 10% to 15% appear to be refractory. This can be due to non-compliance, partial response or true non-response.

As biochemical response to immunosuppressive regimen is the norm, non-response to treatment (lack of more than 25% reduction in transaminases after two weeks) should lead to re-evaluation of the diagnosis. Alternative etiologies such as Wilson’s disease, DILI, NASH should be definitively ruled out. Occasionally variant forms with overlapping features of PBC, PSC preclude full normalization of enzymes.

Compliance with treatment regimen should be ascertained. Measurement of 6 thioguanine (6TGN) levels can be helpful in this regard. A level > 220 pmol per 8 × 108 red blood cells has been shown to be associated with remission in AIH patients[42]. Lack of detectable serum levels would indicate lack of compliance.

Patients who present with a severe acute hepatitis are more likely to fail standard therapy. Limited data is available on management of such patients. Overall mortality is high (19% to 45%) and liver transplant (LT) evaluation should be initiated. A trial of high dose intravenous corticosteroids (> 1 mg/kg) should be given however a definite futility threshold is not defined. Generally, failure to improve model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)-Na, or serum bilirubin within 7 d of initiation of therapy should lead to alternative treatment strategies including LT.

Some patients with AIH fail to achieve full clinical, laboratory and histologic remission after 3-year standard therapy and are said to have incomplete response. Attempt should be made to optimize dosing of the standard regimen (increasing azathioprine to 2 mg/kg per day with addition of 5 to 10 mg of predniso(lo)ne). If complete response remains elusive, then the goal of therapy is to maintain lowest possible biochemical activity while minimizing side effects. Serum transaminases less than 3 times the ULN are acceptable and azathioprine monotherapy at 2 mg/kg per day is usually reasonable.

Fortunately, true non-responders to standard regimens rare (< 5%) and alternative immunosuppressive agents are needed for these patients. Data for use of these agents in AIH is limited and based on small, mainly retrospective case series as no randomized control trial has been conducted. Largest experience is available for calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) cyclosporine and tacrolimus, primarily as salvage therapy with very effective biochemical response (> 90% for both)[43,44]. These drugs are associated with significant long-term side effects including risk of infections, hypertension, renal dysfunction and diabetes mellitus, and once initiated, they need to be continued permanently.

Recently, role of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) monoclonal antibody, infliximab has been shown to have a positive response in difficult to treat patients with AIH[45]. In addition to inducing stable remission, it was shown to have a beneficial effect on liver histology. Its efficacy is supported pathophysiologically by presence of increased TNF secretion and TNF-positive T cells in the liver of patients with AIH. It should be noted, however, that anti-TNF biologics can themselves induce an AIH-like drug induced syndrome.

LT

AIH and its complications account for up to 5% of all liver transplants, typically for acute fulminant presentations or for advanced decompensated cirrhosis. LT for AIH is an effective intervention, with 10-year patient survival of approximately 75%[3]. Both recurrent and “de novo” AIH can occur post liver transplantation, and are treated similarly, using a combination of glucocorticoids and azathioprine. Anti-rejection medications including CNI have not been shown to prevent nor effectively treat recurrent AIH. For refractory cases, switching azathioprine to MMF or changing the calcineurin inhibitor has been recommended[3].

CONCLUSION

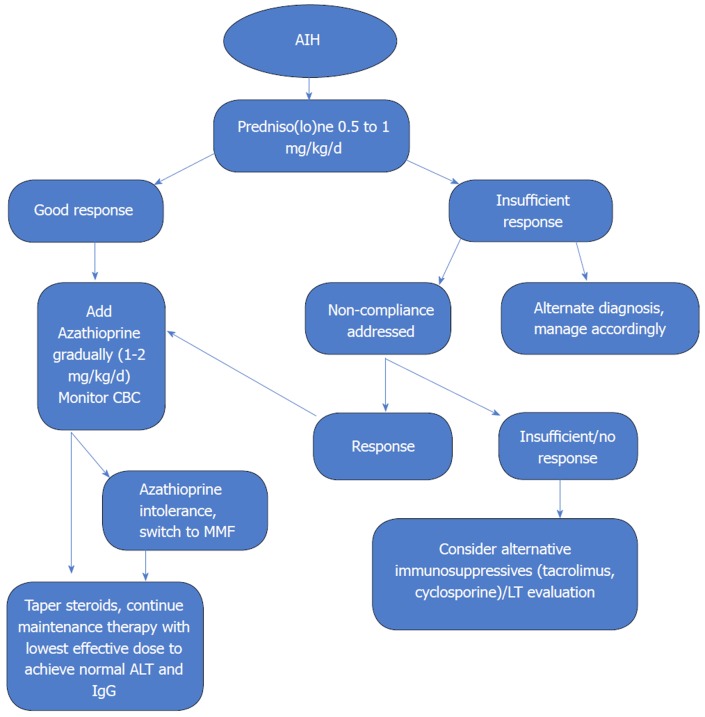

Management of AIH, since its initial description, has seen tremendous growth (Figure 2). Most patients can expect near normal life expectancy and a reasonable quality of life. However, there still exists wide disparity in delivery of care and patient outcomes. Our understanding of the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms, although advanced over the years, is still limited and far away from having significant clinical implications. Rarity and heterogeneity of the disease, excellent response to standard treatment regimens besides economic factors guiding the pharmaceutical industry has limited the development of more specific therapies. Further research into the pathogenesis of the disease may lead to development of more definitive serological diagnostic tests as well as targeted immunotherapies addressing the underlying inflammatory mechanisms in the future.

Figure 2.

Treatment strategy in autoimmune hepatitis. Treatment includes induction and maintenance therapy to achieve biochemical remission. Induction is achieved by steroids and after a positive response (more than 25% reduction in serum aminotransferases after two weeks) is seen, azathioprine is introduced to achieve long term remission. Timely and appropriate maintenance therapy with azathioprine allows for steroid withdrawal. AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; CBC: Complete blood count; MMF: Mycophenolate mofetil; LT: Liver transplant[4].

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Lowe D and John S do not have any affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter pertaining to this manuscript.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: August 28, 2018

First decision: October 5, 2018

Article in press: October 23, 2018

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Andreone P, Macedo G S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

Contributor Information

Dhruv Lowe, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, State University of New York, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY 13202, United States.

Savio John, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, State University of New York, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY 13202, United States. johns@upstate.edu.

References

- 1.Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–938. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’BRIEN EN, GOBLE AJ, MACKAY IR. Plasma-transaminase activity as an index of the effectiveness of cortisone in chronic hepatitis. Lancet. 1958;1:1245–1249. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)92109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Vierling JM; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193–2213. doi: 10.1002/hep.23584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czaja AJ, Donaldson PT. Gender effects and synergisms with histocompatibility leukocyte antigens in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2051–2057. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner M, Prytz H, Ohlsson B, Almer S, Björnsson E, Bergquist A, Wallerstedt S, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Hultcrantz R, Sangfelt P, et al. Epidemiology and the initial presentation of autoimmune hepatitis in Sweden: a nationwide study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1232–1240. doi: 10.1080/00365520802130183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grønbæk L, Vilstrup H, Jepsen P. Autoimmune hepatitis in Denmark: incidence, prevalence, prognosis, and causes of death. A nationwide registry-based cohort study. J Hepatol. 2014;60:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czaja AJ. Autoimmune hepatitis in diverse ethnic populations and geographical regions. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:365–385. doi: 10.1586/egh.13.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberal R, Longhi MS, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:653–664. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czaja AJ, Doherty DG, Donaldson PT. Genetic bases of autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2139–2150. doi: 10.1023/a:1020166605016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal K, Czaja AJ, Jones DE, Donaldson PT. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2000;31:49–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panayi V, Froud OJ, Vine L, Laurent P, Woolson KL, Hunter JG, Madden RG, Miller C, Palmer J, Harris N, et al. The natural history of autoimmune hepatitis presenting with jaundice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:640–645. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landeira G, Morise S, Fassio E, Ramonet M, Alvarez E, Caglio P, Longo C, Domínguez N. Effect of cirrhosis at baseline on the outcome of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:100–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radhakrishnan KR, Alkhouri N, Worley S, Arrigain S, Hupertz V, Kay M, Yerian L, Wyllie R, Feldstein AE. Autoimmune hepatitis in children--impact of cirrhosis at presentation on natural history and long-term outcome. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:724–728. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terrabuio DR, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Carrilho FJ, Cançado EL. Follow-up of pregnant women with autoimmune hepatitis: the disease behavior along with maternal and fetal outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:350–356. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318176b8c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czaja AJ. Autoimmune hepatitis. Part B: diagnosis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;1:129–143. doi: 10.1586/17474124.1.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soloway RD, Summerskill WH, Baggenstoss AH, Geall MG, Gitnićk GL, Elveback IR, Schoenfield LJ. Clinical, biochemical, and histological remission of severe chronic active liver disease: a controlled study of treatments and early prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1972;63:820–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169–176. doi: 10.1002/hep.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vergani D, Alvarez F, Bianchi FB, Cançado EL, Mackay IR, Manns MP, Nishioka M, Penner E; International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Liver autoimmune serology: a consensus statement from the committee for autoimmune serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol. 2004;41:677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Czaja AJ. Performance parameters of the conventional serological markers for autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Czaja AJ. The role of autoantibodies as diagnostic markers of autoimmune hepatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2006;2:33–48. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ. The role of histologic evaluation in the diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis and its variants. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:685–705. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czaja AJ. Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:958–976. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirk AP, Jain S, Pocock S, Thomas HC, Sherlock S. Late results of the Royal Free Hospital prospective controlled trial of prednisolone therapy in hepatitis B surface antigen negative chronic active hepatitis. Gut. 1980;21:78–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamers MM, van Oijen MG, Pronk M, Drenth JP. Treatment options for autoimmune hepatitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hepatol. 2010;53:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Reid F, Donaldson PT, Doherty DG, McCartney M, Mowat AP, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis in childhood: a 20-year experience. Hepatology. 1997;25:541–547. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Czaja AJ. Features and consequences of untreated type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 2009;29:816–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gleeson D, Heneghan MA; British Society of Gastroenterology. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2011;60:1611–1629. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.235259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberal R, de Boer YS, Andrade RJ, Bouma G, Dalekos GN, Floreani A, Gleeson D, Hirschfield GM, Invernizzi P, Lenzi M, Lohse AW, Macedo G, Milkiewicz P, Terziroli B, van Hoek B, Vierling JM, Heneghan MA; International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) Expert clinical management of autoimmune hepatitis in the real world. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:723–732. doi: 10.1111/apt.13907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schramm C, Weiler-Normann C, Wiegard C, Hellweg S, Müller S, Lohse AW. Treatment response in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;52:2247–2248. doi: 10.1002/hep.23840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purnak T, Efe C, Kav T, Wahlin S, Ozaslan E. Treatment Response and Outcome with Two Different Prednisolone Regimens in Autoimmune Hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2900–2907. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4728-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manns MP, Woynarowski M, Kreisel W, Lurie Y, Rust C, Zuckerman E, Bahr MJ, Günther R, Hultcrantz RW, Spengler U, et al. Budesonide induces remission more effectively than prednisone in a controlled trial of patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1198–1206. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:958–963. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510123331502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heneghan MA, Allan ML, Bornstein JD, Muir AJ, Tendler DA. Utility of thiopurine methyltransferase genotyping and phenotyping, and measurement of azathioprine metabolites in the management of patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency and azathioprine intolerance in autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:968–975. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Czaja AJ. Drug choices in autoimmune hepatitis: part B--Nonsteroids. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6:617–635. doi: 10.1586/egh.12.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zachou K, Gatselis N, Papadamou G, Rigopoulou EI, Dalekos GN. Mycophenolate for the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis: prospective assessment of its efficacy and safety for induction and maintenance of remission in a large cohort of treatment-naïve patients. J Hepatol. 2011;55:636–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanzler S, Löhr H, Gerken G, Galle PR, Lohse AW. Long-term management and prognosis of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH): a single center experience. Z Gastroenterol. 2001;39:339–341, 344-348. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Czaja AJ, Menon KV, Carpenter HA. Sustained remission after corticosteroid therapy for type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: a retrospective analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35:890–897. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartl J, Ehlken H, Weiler-Normann C, Sebode M, Kreuels B, Pannicke N, Zenouzi R, Glaubke C, Lohse AW, Schramm C. Patient selection based on treatment duration and liver biochemistry increases success rates after treatment withdrawal in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;62:642–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Czaja AJ. Safety issues in the management of autoimmune hepatitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7:319–333. doi: 10.1517/14740338.7.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dhaliwal HK, Anderson R, Thornhill EL, Schneider S, McFarlane E, Gleeson D, Lennard L. Clinical significance of azathioprine metabolites for the maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2012;56:1401–1408. doi: 10.1002/hep.25760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larsen FS, Vainer B, Eefsen M, Bjerring PN, Adel Hansen B. Low-dose tacrolimus ameliorates liver inflammation and fibrosis in steroid refractory autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3232–3236. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i23.3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarez F, Ciocca M, Cañero-Velasco C, Ramonet M, de Davila MT, Cuarterolo M, Gonzalez T, Jara-Vega P, Camarena C, Brochu P, et al. Short-term cyclosporine induces a remission of autoimmune hepatitis in children. J Hepatol. 1999;30:222–227. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiler-Normann C, Schramm C, Quaas A, Wiegard C, Glaubke C, Pannicke N, Möller S, Lohse AW. Infliximab as a rescue treatment in difficult-to-treat autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2013;58:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]