Abstract

Purpose: To explore experiences of care at the Royal Children's Hospital Gender Service (RCHGS).

Methods: A total of 114 parents and 52 patients of the RCHGS completed an experience of care survey.

Results: Most participants highly rated elements of the family-centered care and multidisciplinary team at RCHGS. The majority were satisfied with the RCHGS (parents: 88%, patients: 92%) and would recommend the service (parents: 95%, patients: 89%). Reductions in distress after participation in RCHGS were noted. Wait time was an area of dissatisfaction. Ideas for improvement concerned information giving, family support provision, and improving access to care.

Conclusion: This study affirms the multidisciplinary family-centered model used at RCHGS.

Keywords: clinical care, gender dysphoria, transgender, access to care, model programs, gender identity

Introduction

The Royal Children's Hospital Gender Service (RCHGS) adopts a family-centred approach to its gender-affirming health care, which acknowledges and supports the gender identity1 of gender diverse children and adolescents up to age 17 from Victoria, Australia. The RCHGS provides assessment, support, and offers developmentally appropriate treatment pathways. For prepubertal children, assistance is provided to develop safe and supportive gender-affirming environments at home and school. Once puberty starts, options for medical treatment include puberty suppression and gender-affirming hormones.2 Referrals to RCHGS have dramatically increased since its single initial referral in 2003.3 In 2016, >220 new referrals were received, and the service has rapidly become the largest publically funded multidisciplinary pediatric gender service in Australia. The RCHGS follows international best practice guidelines in the support and treatment for gender diverse children and adolescents,4,5 and consists of a multidisciplinary team, including mental health specialists (psychologists and psychiatrists), pediatric medical specialists (pediatricians, adolescent medicine physicians, and pediatric endocrinologists), a clinical nurse consultant, a speech therapist, and fertility experts, as well as support from administrative staff. A multidisciplinary approach is recommended4 due to the complex psychological, social, and physical needs of this group.

Gender diverse individuals experience high rates of depressive and anxiety symptomatology, self-harm, and attempted suicide,6–10 likely to be largely related to the negative impact of societal discrimination and prejudice.6–8 Access to appropriate health care is a putative mechanism contributing to improved outcomes for this population. When provided with specialist multidisciplinary gender-affirming health care, the quality of life of gender diverse individuals matches that of the general population.11 Likewise, a study of gender diverse adults found those who had access to medical care they desired were among those with the lowest proportion of depressive symptoms.7 The highest proportion with clinically relevant depressive symptoms were those who desired medical treatment but had not commenced treatment,7 suggesting that the timely delivery of services is a determinant of mental health outcomes.

Measuring the subjective experience of health care can be a useful way to measure outcomes and drive service improvement. Patient satisfaction is increasingly seen as an integral part of quality care and is often a performance indicator within health services.12 Satisfaction with a health service is also associated with many benefits,13 including improved physiological and psychological outcomes for some patients.14,15 This link is demonstrated by Erasmus and colleagues16 who assessed patient satisfaction with an adult gender service in Melbourne, Australia, and found 88% of patients were satisfied with the service while reductions in distress having attended the clinic were noted. Despite these links, there is limited research evaluating experiences of care at gender services in pediatric settings from the perspective of adolescents and parents. We aim to evaluate the experiences of a multidisciplinary family-centered gender service among adolescent patients and parents of the RCHGS.

Methods

Setting and participants

The RCHGS is based at The Royal Children's Hospital (RCH): a large tertiary pediatric hospital in Melbourne, Australia. The patient sample in this study comprised current patients (as of January 2016) of the RCHGS aged 12 years or older. The parent sample was parents of current patients regardless of patients' age. Study eligibility included having sufficient English to complete surveys. Parents from 150 families were invited to participate, as were 93 patients.

Procedure

Approval for this study was granted from the RCH Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC #35273). A list of eligible participants was generated using the RCHGS patient registry. As participants were recruited from a clinical service, parents of RCHGS patients were initially sent an introductory letter from the RCHGS Director advising them that their contact details and demographic information would be provided to the researchers to facilitate being contacted for this study. The letter asked parents to notify the director if they did not agree to this. Two patients who did not have a parent involved in their care were excluded. The contact details of parents who did not opt out were then provided to the research team who subsequently phoned parents and requested that parents nominate one parent per family to participate in the study, provide permission for their child to be surveyed if they met age criteria, and provide an e-mail address to facilitate survey administration.

Data were collected using a secure web-based application, REDCap,17 hosted at Murdoch Children's Research Institute. Parent and patient information letters and survey links were e-mailed to parents; parents of patients aged 12 years or older were asked to forward the patient's letter and survey to their child if they agreed to them participating. In some instances, patients aged 18 years or older provided consent for themselves. Participants completed online surveys, or pen-and-paper or telephone surveys if preferred. Survey completion was considered implied consent. Surveys took ∼10 min to complete and were undertaken during March–April 2016. After survey completion, information about support services for gender diverse patients and families was provided.

Measures

A separate parent and a patient survey was used to measure the following.

Demographics and appointment history

Participant demographic information, including age, gender identity, and postcode, was collected using open-ended questions. Information about country of birth (Australia/another country), whether English was spoken as a first language (yes/no), and information about RCHGS appointment history (months on wait list and number of appointments) was also collected.

Experiences of care

An instrument measuring patient satisfaction with adult gender services in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia12,16,18,19 was adapted with permission from the original author. In this study, experiences of care were assessed by a 32-item parent instrument and a 30-item patient instrument. Participants reported on the health care received using a five-point scale (“very poor” –“excellent”), distress levels before first appointment and at the time of survey completion on a four-point scale (“no problem”–“severe”), how helpful clinicians were on a four-point scale (“very unhelpful”–“very helpful”), satisfaction with family-centered care and administration on a five-point scale (“very dissatisfied”–“very satisfied”), and if participants would recommend the service to a friend/relative with similar concerns (five-point scale: “strongly disagree”–“strongly agree”). Open-ended questions about helpful or beneficial elements of care, areas for improvement/change, additional services, and further comments were included.

Analysis

Quantitative data analysis was undertaken by coauthor G.M. in STATA (version SE 13.0). For analyses, responses to satisfaction items were collapsed to three categories: very dissatisfied/dissatisfied, neither dissatisfied nor satisfied, satisfied/very satisfied. Helpfulness responses were collapsed into unhelpful/very unhelpful versus helpful/very helpful.

Frequencies and percentages of categorical data and means and standard deviations of continuous data were calculated based on valid cases. Inductive content analysis was undertaken to formulate categories from open-ended questions.

Results

Sample characteristics

There were 166 surveys completed; 114 parents and 52 patients constituting response rates of 76% and 56%, respectively. The mean age of parents was 45.1 (SD 7.59) and patients 16.4 (SD 1.85). The majority of participants were Australian born (parents: 82.5%, patients: 90.4%) and spoke English as their first language (parents: 92.0%, patients: 94.2%). Parents comprised mainly of self-described “female/woman/cis-woman” (87.5%). Patients' self-described gender identity varied; common responses included “male” (44.2%), “female”/“girl”/“woman” (34.6%), “male transgender” (5.8%) and “gender fluid”/“nonbinary”/“transgender/nonbinary” (5.8%). Families had been attending the RCHGS from 1 month to >3 years, with 58.2% attending for 12+ months. More than 80% had attended at least three appointments, and half (50.9%) were on the wait list for 6+ months.

Description of health care received

Participants reported the health care received at RCHGS positively, with 95.6% of parents and 82.7% of patients describing this as “good” or “excellent”. Most parents and patients reported clinicians of all disciplines as helpful/very helpful (proportions ranging from 83.3% to 98.8%).

Distress before first appointment and now

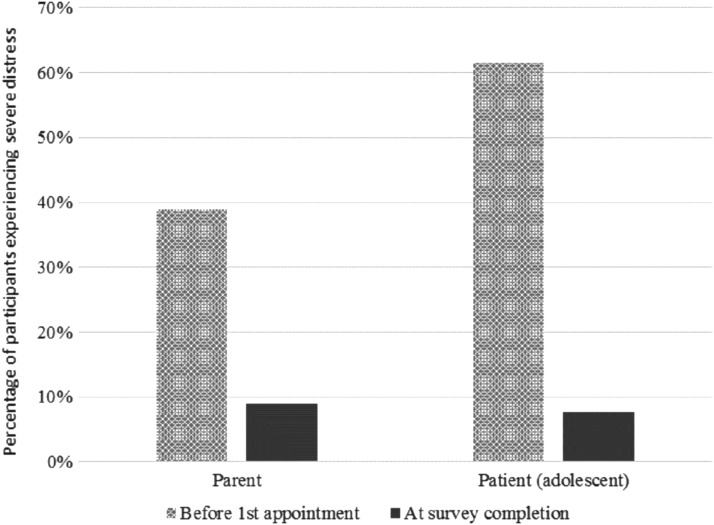

Figure 1 shows changes in severe distress described before first appointment and at the time of survey completion. A trend was noted whereby there was a reduced proportion of parents and patients reporting severe distress and greater proportions reporting mild distress over time.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of parents and patients experiencing severe distress due to patients' gender concerns.

Satisfaction with family-centered care

The majority of participants were satisfied with the RCHGS overall (parents: 88.3%, patients: 92.3%) and would recommend the service (parents: 94.6%, patients: 88.6%). High levels of satisfaction with all aspects of family-centered care were reported (Table 1). More than 90% of patients and parents reported being satisfied/very satisfied with health staff in the areas of having knowledge in gender and maintaining confidentiality, and respect for patients' privacy by outpatient and administration services. The lowest level of satisfaction was regarding wait time for first appointment.

Table 1.

Levels of Satisfaction with Patient and Family-Centered Practice at the Royal Children's Hospital Gender Service

| Parents | Patients | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissatisfied/very dissatisfied | Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied | Satisfied/very satisfied | Dissatisfied/very dissatisfied | Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied | Satisfied/very satisfied | |||||||||

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | N | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Understand young person's concerns | 112 | 1.8 | 2 | 8.9 | 10 | 89.3 | 100 | 52 | 7.7 | 4 | 7.7 | 4 | 84.6 | 44 |

| Understand family's concerns | 112 | 4.5 | 5 | 9.8 | 11 | 85.7 | 96 | 52 | 3.8 | 2 | 15.4 | 8 | 80.8 | 42 |

| Are caring and warm | 112 | 1.8 | 2 | 8.0 | 9 | 90.2 | 101 | 52 | 7.7 | 4 | 7.7 | 4 | 84.6 | 44 |

| Respect family's opinions and feelings | 110 | 2.7 | 3 | 8.2 | 9 | 89.1 | 98 | 52 | 1.9 | 1 | 17.3 | 9 | 80.8 | 42 |

| Respect young person's opinions and feelings | 111 | 0.9 | 1 | 4.5 | 5 | 94.6 | 105 | 52 | 5.8 | 3 | 11.5 | 6 | 82.7 | 43 |

| Have knowledge in the area of gender | 110 | 0.0 | 0 | 6.4 | 7 | 93.6 | 103 | 52 | 3.9 | 2 | 5.8 | 3 | 90.4 | 47 |

| Maintain young person's confidentiality | 111 | 0.9 | 1 | 2.7 | 3 | 96.4 | 107 | 52 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 96.2 | 50 |

| Encourage me to ask questions | 110 | 4.5 | 5 | 8.2 | 9 | 87.3 | 96 | 52 | 5.8 | 3 | 9.6 | 5 | 84.6 | 44 |

| Information on gender or gender management options (if provided) | 85 | 4.7 | 4 | 9.4 | 8 | 85.9 | 73 | 49 | 4.1 | 2 | 14.3 | 7 | 81.6 | 40 |

| Information of community gender supports and information (if provided) | 86 | 5.8 | 5 | 19.8 | 17 | 74.4 | 64 | 42 | 4.8 | 2 | 28.6 | 12 | 66.7 | 28 |

| Administration staff | 110 | 7.3 | 8 | 11.8 | 13 | 80.9 | 89 | 50 | 8.0 | 4 | 24.0 | 12 | 68.0 | 34 |

| Staff at outpatients' desk | 111 | 4.5 | 5 | 9.0 | 10 | 86.5 | 96 | 52 | 1.9 | 1 | 19.2 | 10 | 78.8 | 41 |

| Respect for young person's privacy by administration/outpatients | 111 | 0.9 | 1 | 8.1 | 9 | 91.0 | 101 | 51 | 2.0 | 1 | 7.8 | 4 | 90.2 | 46 |

| Overall satisfaction with RCHGS | 111 | 1.8 | 2 | 9.9 | 11 | 88.3 | 98 | 52 | 7.7 | 4 | 0.0 | 0 | 92.3 | 48 |

| Wait time for first appointment | 110 | 33.6 | 37 | 12.7 | 14 | 53.6 | 59 | 51 | 29.4 | 15 | 27.5 | 14 | 43.1 | 22 |

RCHGS, Royal Children's Hospital Gender Service.

Helpful aspects and areas for improvement (qualitative)

When asked what had been most helpful, beneficial, or valuable about RCHGS, participants expressed their appreciation of clinician's respectful and caring communication, clinicians sharing information, and the therapeutic clinician–patient relationship. Parents articulated that the process was validating and normalizing. Patients were grateful to access medical treatment. Suggestions for service improvements included additional resources to reduce wait time and increase frequency of appointments. Participants expressed requiring more detailed information during assessment and treatment. Parents stressed the need for additional support for families. Suggestions for services included family support, regional services to improve and broaden access, and assistance transitioning from pediatric to adult services. Examples of quotes reflecting these themes are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Helpful Aspects of Royal Children's Hospital Gender Service and Suggestions for Improvement

| Theme | Example quotes |

|---|---|

| Helpful, beneficial, or valuable aspects of the gender service: | |

| Appreciation of clinician's respectful communication, clinicians sharing information, and the therapeutic clinician–patient relationship | “I had so many questions about things. They were a wealth of information and provided a place where I could talk freely and openly without feeling judged. This was invaluable.” Parent |

| “I find having someone so friendly and respectful to talk to really puts my mind at ease. Unlike many other appointments I have elsewhere, I look forward to coming to the appointments I make at the RCH.” Adolescent | |

| Validating process and normalizing experience | “Someone to talk to you as though this is normal. [Clinicians] both normalised the situation, explaining it wasn't weird or strange, just another health condition that needed care.” Parent |

| Grateful to access medical treatment | “To gain access to professional assessment and guidance as well as reassurance that our attitudes and treatment of our child is valid and appropriate. This also gave us credibility when explaining our child to family and friends, community members and schools.” Parent |

| “It's the literal only way someone my age can get hormone therapy” Adolescent | |

| Suggestions for change/improvement: | |

| Additional resources | “Extra doctors so that it doesn't take so long to get an appointment.” Parent |

| “The waiting time. Yes, it may not seem like very long but when your body is mutating everyday is like torture.” Adolescent | |

| Require more detailed information during assessment and treatment | “Clearer intake process so we understand what to expect and how we can make the most of our attendance.…We have felt lost in a big system.” Parent |

| Additional support for families | “Separate mental health supports for parents.” Parent |

| Additional services that the gender service should provide; | |

| Family support | “Peer support for both the child and the parents and siblings” Parent |

| Regional services | “I think it would be good to have outreach clinics in the bigger country towns.” Parent |

| Assistance transitioning from pediatric to adult services | “Either see over 18s at the RCH or help with transition into adult services. I felt that the services and support dropped off when I turned 19.” Adolescent |

RCH, Royal Children's Hospital.

Discussion

This study extends our understanding of health service users' experiences of care at a multidisciplinary pediatric gender service, from parent and patient perspectives. The study revealed that patients and parents reported reduced distress having attended the RCHGS, found clinicians of all disciplines helpful, and had high levels of satisfaction with family-centered care, indicating that a multidisciplinary treatment model is accepted by this pediatric population and their families. Areas for improvement were the need to address the wait list and frequency of appointments, family support resources, and additional information provision. These findings can guide service improvements and inform other health services for this growing patient population.

In this study, most participants reported positively on the care received at RCHGS. The importance of this is twofold: first, satisfaction with health services is associated with improved health and well-being14,15; the synchronicity of this being imperative given the mental health vulnerabilities of this patient group, and second, it is considered an integral indicator of quality care.12 The level of satisfaction with RCHGS is comparable with that in adult gender services around the world.16,18,19

This study found that patient distress declined after attending the service, similar to studies in adult populations.16,18 This is an important finding in light of the service's aim to improve the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria. Parent distress also improved, suggesting that the RCHGS may have a broader impact on parental well-being. This shows promise as families raising gender diverse children can experience grief,20 and parental support is associated with reduced adolescent distress.21

The need to address the waiting list was highlighted in this study; at the time there was a wait period of >12 months before patients were typically first seen by a pediatrician and mental health clinician as part of a multidisciplinary assessment clinic. Internationally, the availability of sufficiently trained specialists working in this area is limited,4 and when coupled with increasing referrals this results in lengthy wait times, which is a highlighted reason for dissatisfaction.22 Since this study, the RCHGS has introduced a single-session clinic as its standard entry point, led by the RCHGS clinical nurse consultant, which has reduced wait time for face-to-face clinical access to the RCHGS.23 Key components of the clinic include a biopsychosocial assessment (which is used to identify triage pathways) and provision of individualized support, education, and linkages to community services. Other gender services may benefit from implementing similar innovations. Building capacity in the health care sector through medical education and training in transgender health is imperative for ensuring optimal, accessible, and equitable care.24,25

There are some limitations of this study. This study used a convenience sample; satisfied individuals may be more likely to participate presenting a potential nonresponse bias.13 Whether this sample is representative of the RCHGS patient group and gender diverse youth in Australia is also unknown. Furthermore, this study relied on retrospective reporting, which raises potential recall bias; further prospective longitudinal research is needed. Finally, this study surveyed patients aged 12 years or older; thus, the results may not represent the entire patient population. Future efforts could focus on adapting the survey to also capture younger patients' experiences.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated high levels of satisfaction with a pediatric gender service, confirming that a multidisciplinary assessment and family-centered care model is considered acceptable for this patient population. Areas for improvement could be targeted as this service evolves. This study's findings can be used by those developing similar services that face issues around the complexities of care for this group and ongoing demand for services.

Acknowledgments

This project was undertaken as part of Gabrielle McKie's qualification for a Doctor of Medicine degree at The University of Melbourne.

Abbreviations Used

- RCH

Royal Children's Hospital

- RCHGS

Royal Children's Hospital Gender Service

Disclaimer

Results of this research were presented as part of the requirements of Gabrielle McKie's qualification for a Doctor of Medicine degree, and as a poster at the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) conference in Amsterdam in 2016.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Cite this article as: Tollit MA, Feldman D, McKie G, Telfer MM (2018) Patient and parent experiences of care at a pediatric gender service, Transgender Health 3:1, 251–256, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2018.0016.

References

- 1. Schuster MA, Reisner SL, Onorato SE. Beyond bathrooms—meeting the health needs of transgender people. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:101–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Royal Children's Hospital Gender Service. Royal Childrens Hospital Gender Service: Background, Funding and Program Logic Model. 2016. Available at: www.rch.org.au/adolescent-medicine/gender-service/The_Gender_Service_background,_funding_and_program_logic Accessed December18, 2018

- 3. Telfer M, Tollit M, Feldman D. Transformation of health-care and legal systems for the transgender population: the need for change in Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:1051–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165–232 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869–3903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Couch M, Pitts M, Mulcare H, et al. Tranznation: A Report on the Health and Wellbeing of Transgendered People in Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne: The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hyde Z, Doherty M, Tilley PJM, et al. The First Australian National Trans Mental Health Study: Summary of Results. Perth, Australia: School of Public Health, Curtin University, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strauss P, Cook A, Winter S, et al. Trans Pathways: The Mental Health Experiences and Care Pathways of Trans Young People. Summary of Results. Perth, Australia: Telethon Kids Institute, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hillier L, Jones T, Monagle M, et al. Writing Themselves in 3: The Third National Study on the Sexual Health and Wellbeing of Same Sex Attracted and Gender Questioning Young People. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marshall E, Claes L, Bouman WP, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality in trans people: a systematic review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Vries A, McGuire J, Steensma T, et al. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics. 2014;134:696–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davies A, Bouman WP, Richards C, et al. Patient satisfaction with gender identity clinic services in the United Kingdom. Sex Relation Ther. 2013;28:400–418 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aharony L, Strasser S. Patient satisfaction: what we know about and what we still need to explore. Med Care Rev. 1993;50:49–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hall JA, Feldstein M, Fretwell MD, et al. Older patients' health status and satisfaction with medical care in an HMO population. Med Care. 1990;28:261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pascoe GC. Patient satisfaction in primary health care: a literature review and analysis. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6:185–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Erasmus J, Bagga H, Harte F. Assessing patient satisfaction with a multidisciplinary gender dysphoria clinic in Melbourne. Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23:158–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bockting W, Robinson B, Benner A, Scheltema K. Patient satisfaction with transgender health services. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30:277–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wylie KR, Fitter J, Bragg A. The experience of service users with regard to satisfaction with clinical services. Sex Relation Ther. 2009;24:163–174 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wahlig JL. Losing the child they thought they had: therapeutic suggestions for an ambiguous loss perspective with parents of a transgender child. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2015;11:305–326 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simons L, Schrager SM, Clark LF, et al. Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:791–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ellis SJ, Bailey L, McNeil J. Trans people's experiences of mental health and gender identity services: a UK study. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2015;19:4–20 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eade DM, Telfer MM, Tollit MA. Implementing a single-session nurse-led assessment clinic into a gender service. Transgender Health. 2018;3:43–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Awosogba T, Betancourt JR, Conyers FG, et al. Prioritizing health disparities in medical education to improve care. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1287:17–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG Jr., et al. Transgender health care: improving medical students' and residents' training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:37–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]