Abstract

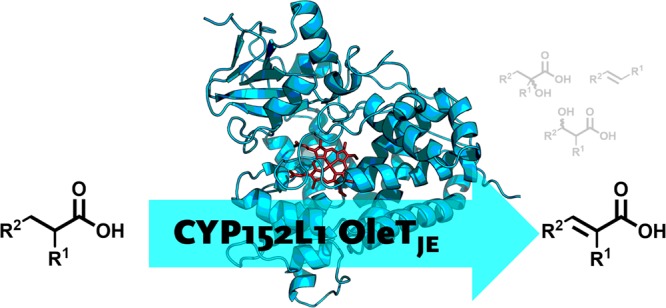

The majority of cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) predominantly operate as monooxygenases, but recently a class of P450 enzymes was discovered, that can act as peroxygenases (CYP152). These enzymes convert fatty acids through oxidative decarboxylation, yielding terminal alkenes, and through α- and β-hydroxylation to yield hydroxy-fatty acids. Bioderived olefins may serve as biofuels, and hence understanding the mechanism and substrate scope of this class of enzymes is important. In this work, we report on the substrate scope and catalytic promiscuity of CYP OleTJE and two of its orthologues from the CYP152 family, utilizing α-monosubstituted branched carboxylic acids. We identify α,β-desaturation as an unexpected dominant pathway for CYP OleTJE with 2-methylbutyric acid. To rationalize product distributions arising from α/β-hydroxylation, oxidative decarboxylation, and desaturation depending on the substrate’s structure and binding pattern, a computational study was performed based on an active site complex of CYP OleTJE containing the heme cofactor in the substrate binding pocket and 2-methylbutyric acid as substrate. It is shown that substrate positioning determines the accessibility of the oxidizing species (Compound I) to the substrate and hence the regio- and chemoselectivity of the reaction. Furthermore, the results show that, for 2-methylbutyric acid, α,β-desaturation is favorable because of a rate-determining α-hydrogen atom abstraction, which cannot proceed to decarboxylation. Moreover, substrate hydroxylation is energetically impeded due to the tight shape and size of the substrate binding pocket.

Keywords: biocatalysis, cytochrome P450, peroxygenase, hydroxylation, desaturation, decarboxylation, density functional theory, valence bond modeling

Introduction

The heme-containing cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) demonstrate broad substrate tolerance as they are vital for the metabolization of xenobiotics and drug molecules,1 as well as for the biosynthesis of hormones.2 Due to this substrate promiscuity and their regio- and stereospecificity, they have become the topic of extensive research. CYP enzymes catalyze aliphatic and aromatic C–H oxidations,3 epoxidations of olefins, sulfoxidations, dehalogenations, N- and O-dealkylations, desaturations, and oxidative decarboxylations.4 More recently, “non-natural” applications of CYPs have been enabled through bioengineering their structure and function.5 Specifically, they have been utilized for the introduction of nitrogen, boron, or silicon into organic frameworks6 or carbene- and nitrene-mediated reactions.7

The vast majority of CYP monooxygenases require one molecule of O2, two protons, and two electrons, which are transferred one at a time from an external redox partner throughout the catalytic cycle.1,8 A common issue of CYP monooxygenases is the uncoupling reactions, leading to the loss of redox equivalents in the form of hydrogen peroxide or superoxide anions which in turn harm the enzyme. A handful of CYPs have evolved the ability to utilize hydrogen peroxide as both electron- and oxygen-source instead, by reversing the peroxide shunt that leads to uncoupling.9 These CYP-“peroxygenases” belong to the CYP152 subfamily, do not require a redox partner, and are able to hydroxylate carboxylic acids. A well-studied peroxygenase from the CYP152 family is the CYP OleTJE (CYP152L1) from Jeotgalicoccus sp. ATCC 8456.10 This enzyme catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of long-chain fatty acids yielding terminal olefins alongside α- and β-hydroxylation (Scheme 1a).11 With hydrogen peroxide, the enzyme works as peroxygenase; however, it was also shown to efficiently work as monooxygenase.10c Recent results demonstrated that, in this case, OleTJE utilizes electrons derived from a redox system which are then lost by uncoupling and re-enter the catalytic cycle as hydrogen peroxide. Therefore, Compound I can only be formed with hydrogen peroxide, and the enzyme predominantly acts as peroxygenase.9e Since selective oxidative decarboxylation opens access to bioderived olefins from carboxylic acids, understanding the mechanism and product formation of these enzymes is an important basis for the development of more efficient and selective enzyme variants.

Scheme 1. (a) Substrates 1a–5a and Products Obtained by CYP152-Transformation of Fatty Acids and b) Potential Products and Their Stereoisomers: 1b–5b from Oxidative Decarboxylation, 1c–5c from α–Hydroxylation, and 1d–5d from β-Hydroxylation.

Most studies on the reaction profile of CYP152 enzymes in general, but OleTJE especially, focused on identifying main product distributions rather than a careful calibration with authentic references and quantification of all products.9g,10a,10c,12 On top of that, information regarding stereochemical preferences of OleTJE catalysis remains scarce.13 Overall, the enzyme’s broad reactivity produces not only enantiomeric α- or β-hydroxy acids, but also regioisomeric alkenes. For instance, in the reaction of rac-2a, 13 different compounds must be considered (Scheme 1b).

Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) studies, focused on product distributions in CYP OleTJE for oxidative decarboxylation versus α- and β-hydroxylation, showed14 and stopped-flow experiments confirmed10,11 that all products originate from a rate-determining hydrogen atom abstraction of either Cα or Cβ.

To address major questions related to the structure, function, and substrate scope of CYP152 peroxygenases we decided to perform a combined experimental and computational study into these systems: The primary oxidation-product distribution for a structurally diverse set of carboxylic acids 1a–5a bearing a stereocenter at Cα (Scheme 1a), using peroxygenases OleTJE, CYPCla from Clostridium acetobutylicum (CYP152A2),15 and CYPBSβ from Bacillus subtilis (CYP152A1),16 was evaluated and revealed an unprecedented α,β-desaturation activity. The origin of the different reactivities was rationalized by computational methods based on an active site complex of CYP OleTJE.

Methods

General procedure for Biotransformations with OleT–CamAB–FDH reaction cascade

Biotransformations of substrates using OleTJE were performed as previously described.10c A typical reaction mixture contained purified OleTJE (6 μM), putidaredoxin CamAB (0.05 U mL–1), catalase (500 U mL–1), substrate (10 mM), ethanol (5% v/v), potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5, 100 mM), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) or NAD+ (200 μM), formate dehydrogenase (FDH; 2 U mL–1), and ammonium formate (100 mM). All reactions were performed at atmospheric pressure at room temperature (or 4 °C) in a 1 mL volume in a 4 mL glass vial closed with a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) septum with shaking at 170 rpm for 24 h. The activity of the CamAB system and the concentration of active, purified OleTJE were determined prior to each biotransformation using a cytochrome c-based activity assay and CO-titration, respectively (Supporting Information). Biotransformations as well as negative control experiments (without OleTJE) were performed in triplicate for each substrate and were stopped by freezing the samples at −20 °C.

Biotransformations with CYPCla and CYPBSβ

Biotransformations using CYPCla and CYPBSβ were done in 4 mL glass vials sealed with a PTFE septum with shaking at 170 rpm for 24 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture contained purified enzyme (6 μM), substrate (10 mM), and ethanol (5% v/v). H2O2 was used as the sole oxidant, and supply was provided using a syringe pump (kdScientific). A flow of 1.6 mM H2O2 h–1 (5 μL h–1 from a 320 μM stock solution) was set, and 16 mM (50 μL) was added in total. Biotransformations and negative control experiments (without enzyme) were performed in triplicate for each substrate and were stopped by freezing the samples at −20 °C.

Computation

Calculations were performed using previously described and calibrated methods.17 Density functional theory (DFT) was applied using the unrestricted B3LYP hybrid density functional theory18 for geometry optimizations and frequencies in the gas phase. The mechanism for the activation of (R)- and (S)-2-methylbutyric acid (2a) by CYP Compound I (CpdI) was studied. The initial calculations used a simplified model (A) containing an iron(IV)-oxo porphyrin radical cation model for CpdI, whereby the axial cysteinate residue was abbreviated with thiolate, and all porphyrin substituents were replaced by hydrogen atoms: [FeIV(O)(Por+•)(SH)]. The general reactivity landscape and electronic structure of intermediates and transition states with the (S)-enantiomer of the substrate, leading to either hydroxylation, desaturation, or decarboxylation products, were calculated. In all calculations for model A, the geometry optimizations were done with a 6-31G* basis set19 on all atoms, except on iron where LANL2DZ with effective core potential (ECP) was used (basis set BS1).20 To improve the energies a single point with a larger basis set, i.e., 6-311+G* on all atoms, was performed (basis set BS2). Calculations were run in the Gaussian 09 software package21 and were done on the lowest-energy doublet and quartet spin states.

In a second set of calculations a comprehensive cluster model was investigated (model B), based on a detailed analysis of the protein structure and dynamics. In particular, with molecular dynamics simulations the protein and especially the substrate binding pocket flexibility was investigated. However, these studies (Supporting Information, Figures S1 and S2) showed little flexibility in substrate positioning and dynamics. Therefore, we decided to use an expanded cluster model rather than QM/MM for detailed studies on the mechanism of substrate activation. These cluster models have been shown to give an accurate representation of enzyme active site activities and reproduce experimental chemo- and regioselectivity patterns.22 Thus, the small model was expanded with residues representing the substrate binding pocket (Figure S4) until structure convergence was achieved using procedures as described by Liao et al. (see also Figure S10).23 The energies and structures of the two models were comparable, and hence the calculations were continued with model A. The (S)- and (R)-enantiomers of the substrate were docked into the 4L40 protein databank (pdb) file11a with the SwissDock web service.24 The 4L40 pdb file is a substrate bound resting state structure, but we removed the original substrate and tested various alternative stable substrate binding positions. A total of three distinct low-energy (R)-isomers and five (S)-isomers were selected as the starting points of the calculations. Based on these structures and the results from the MD simulations, a model was created that contained the iron(IV)-oxo porphyrin cation radical with thiolate axial ligand and substrate (as in model A above) and the side chains of residues located close to the substrate in the active site (Leu78, Phe79, Ile170, Pro246, Ala249, Phe291, and Val292; Scheme 2 and Figure S4, Supporting Information). The total model included 163 atoms, and constraints were placed on protein backbone atoms to keep the features of the substrate binding pocket; these atoms are highlighted with an asterisk in Scheme 2. A trimmed proline residue was protonated to account for the lost backbone carbon bond. The system was overall charge neutral and was calculated in the lowest doublet and quartet spin states.

Scheme 2. Active Site Cluster Model of CYP OleTJE with Substrate Bound.

Atoms highlighted with an asterisk were fixed during the geometry optimization.

The studies on model B use the unrestricted B3LYP-GD318,25 density functional method in combination with the def2-SVP26 basis set on all atoms (basis set BS3). An enlarged basis set (BS4) that incorporates def2-TZVP on all atoms and an implicit solvent model, i.e., the polarized continuum model with water as dielectric constant, was employed to correct the energies for all results for model B. Free energies reported here use entropic and thermal (at 298 K) corrections.

Transition states were located by initially running constraint geometry scans between reactants and intermediates (or in between intermediates and products) and vice versa, whereby one degree of freedom was fixed (the reaction coordinate), while all other degrees of freedom were allowed to relax. The maxima of these geometry scans were subjected to a full transition state search in Gaussian using default settings.

Results and Discussion

Identification of Desaturation Activity of OleTJE

The biotransformation of myristic acid (1a), 2-methylbutyric acid (2a), and 2-phenylbutyric acid (3a) by CYP was studied. Even though OleTJE was recently demonstrated to be a true peroxygenase,9e the established OleTJE–CamAB–FDH reaction system10c,27 proved to be very productive in biotransformations and was applied herein. Figure 1 gives the individual product distributions for the reactions of rac-1a, rac-2a, and rac-3a in OleTJE.

Figure 1.

OleTJE–CamAB–FDH catalyzed transformation of substrates 1a–3a at room temperature and Sankey representation of the product distribution. The width of the lines corresponds to the relative amount of substrate that was converted (left-hand side) and the relative amount of product that was formed (right-hand side).

With substrate 1a, OleTJE yielded a mixture of alkene (1b) and 3-hydroxymyristic acid (1d) as sole products with an overall conversion of 11% matching previous reports.10c However, as the product distribution highly depended on the reaction conditions, alternative redox partners were reported to cause also α-hydroxylation,11a,13,28 which was not observed here. By contrast, CYP OleTJE converted 3a through decarboxylation to form 3b and α-hydroxylation to generate 3c, again, matching previous reports with this substrate.13 Remarkably, strict (R)-hydroxylation of 1a and 3a was observed leading to (R)-1c and (R)-3d with high ee, while a slight (S)-preference prevailed for the α-chiral substrate 3a (Table 1).

Table 1. Products Obtained from the Conversion of 1a–5a by OleTJE, CYPCla, or CYPBSβa.

| ox.

decarboxylation |

α-hydroxylation |

β-hydroxylation |

α,β-desaturation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| enzyme | substrateb | [mM] (ee [%]) | [mM]c (E/Z) | TON (E/Z) | [mM] (ee [%]) | TON | [mM]c (ee [%]) | TON | [mM]c (E/Z) | TON (E/Z) |

| OleTJE (rt) | 1a | 7.77 | 0.78 | 130 | 332 | 0.32 (>99R) | 53 | |||

| 2a | 2.64 (65R) | traces | 0.99 (68R) | 165 | 1.95 (97/3) | 315/10 | ||||

| 3a | 6.59 (17R) | 0.46 (1.6/1) | 47/30 | 1.02 (95R) | 170 | |||||

| 4a | 5.89 (39R) | 1.99 (>95R) | 332 | 0.49 (98/2) | 80/2 | |||||

| 5a | 3.40 (96R) | 1.40 (<10) | 233 | 3.00 | 500 | |||||

| OleTJE (4 °C) | 1a | 7.31 | 1.16 | 193 | 332 | 0.15 (>99R) | 25 | |||

| 2a | 5.69 (<10) | traces | 0.44 (20R) | 74 | 0.83 (96/4) | 133/5 | ||||

| 3a | 6.22 (<10) | 0.54 (1.7/1) | 57/33 | 1.13 (>95R) | 188 | |||||

| 4a | 7.03 (11R) | 1.30 (>95R) | 217 | 0.40 (99/1) | 66/1 | |||||

| 5a | 4.28 (35R) | 0.94 (<10) | 157 | 2.63 | 438 | |||||

| CYPCla | 1a | 1.18 | 4.47 (rac) | 745 | ||||||

| 2a | 6.86 (17R) | 1.73 (65R) | 288 | |||||||

| 3a | 0.61 (93R) | 8.82 (12R) | 1470 | |||||||

| 4a | 7.51 (21R) | 1.37 (>95R) | 228 | |||||||

| 5a | 1.65 (99R) | 5.21 (19R) | 868 | |||||||

| CYPBsβ | 1a | 0.94 | 1.56 | 260 | 0.49 (67R) | 82 | 0.96 (>99R) | 16 | ||

| 2a | 3.89 (74R) | 3.66 (60R) | 610 | |||||||

| 3a | 2.57 (89R) | 4.92 (74R) | 820 | |||||||

| 4a | 3.70 (81R) | 3.66 (>95R) | 610 | 0.46 (96/4) | 74/3 | |||||

| 5a | 2.43 (>99R) | 3.91 (79R) | 652 | 0.85 (93R)d | 142 | 0.13 | 22 | |||

Error-margins can be found in the Supporting Information. Reactions were performed in triplicate with 10 mM substrate for 24 h at either room temperature (rt) or 4 °C.

Secondary oxidation products (e.g., keto acids) were not measured and contribute to the incomplete recovery.

No terminal products (alkenes or hydroxylation products) were detected.

Chiral center is not formed by hydroxylation but is already present in the substrate; traces = only traces of product were detected in headspace gas chromatography with mass spectroscopy (GC-MS; not quantified).

For the small 2-methylbutyric acid (2a) the (S)-form was preferred, and α-hydroxylation produced (R)-2c29 in moderate enantioselectivity. This fits to the trend that CYP450s tend to activate the weakest C–H bond of a substrate,30 which in this case is Cα. Interestingly, besides the formation of minor amounts of decarboxylation product (2b) and α-hydroxylation, OleTJE also led to desaturation of 2a leading to (E/Z)-2,3-dimethylacrylic acid (E/Z-2e), which is the first time that fatty acid desaturation has been observed in CYP152 reactions (Figure 1).

CYP450 desaturations have been observed in rare cases by enzymes from other CYP classes, such as the desaturation of valproic acid demonstrated by Rettie et al. in 1987, or desaturations of ethyl carbamate, sterols, and alkylbenzenes and the terminal desaturation of lauric acid.31 Density functional theory studies on the regioselective hydroxylation versus desaturation of valproic acid and ethyl carbamate showed a spin-selective reaction mechanism with dominant hydroxylation on the high-spin surface and a mixture of products on the low-spin state.32 Desaturation reactivity was also already suggested for the CYP152 family member OleTJE. However, a combination of overoxidation to the ketone, followed by enolization during the derivatization step, was likely its origin rather than enzyme catalyzed desaturation.28 Herein, nonenzymatic pathways, such as spontaneous desaturation, dehydration of a hydroxylated metabolite, as well as enzymatic secondary activities of OleTJE and CYPBsβ on hydroxylated products (e.g., 2c or 2d), were excluded with a series of control experiments (Supporting Information).

Reactivity of OleTJE, CYPCla, or CYPBSβ

Despite the close structural homology of substrates 2a and 3a, no desaturation products could be detected for the latter. To understand the reactivity differences of OleTJE with 2a and 3a, the further substrates 2-phenylbutanoic acid (4a) and 2-phenylpropanoic acid (5a) were included in the study, and the product distributions for all substrates were investigated with OleTJE (at both room temperature and 4 °C) and the additional CYP152 orthologues CYPCla and CYPBSβ. While again the OleTJE–CamAB–FDH reaction system was used for the OleTJE-transformations, CYPCla and CYPBSβ studies were performed using H2O2 as the oxidant. All metabolites were carefully quantified, and stereoselectivities and absolute configurations were measured for the products and the substrate (Table 1).

The transformation of all substrates by CYPCla yielded α-hydroxylation products exclusively, whereas OleTJE and CYPBSβ generated a mixture of products. Oxidative decarboxylation was observed for the reactions of OleTJE with 1a and 3a and for CYPBsβ with 1a. Moreover, α,β-desaturation was found for OleTJE with 2a, 4a, and 5a, as well as for CYPBsβ with 4a and 5b. As such, OleTJE and CYPBSβ give analogous reactivity patterns and product distributions, but yields and turnovers vary. In the majority of studies on OleTJE, only linear fatty acids or diacids were investigated as substrates,10,11,13,28,33 which do not react through desaturation, and hence this activity has never been reported before.

The overall substrate conversion as a function of isozyme is divergent. In the case of OleTJE, the highest conversion and turnover number (TON) was obtained for substrate 5a (44%, 733 TON). The reaction temperature had a slight impact on the overall reactivity (e.g., 36% conversion, 595 TON, based on the sum of recovered products). By contrast, with CYPCla and CYPBSβ the highest conversion was with 3a instead. It needs to be mentioned that secondary oxidation products (e.g., keto acids) were not measured and contribute to the incomplete recoveries that were found.

With OleTJE, an almost 2:1 mixture of desaturation product over α-hydroxy acid was obtained with substrates 2a and 5a. Interestingly this ratio is reversed for 4a (1:4), which may be caused by an altered orientation of the substrate in the active site, forced by the additional methyl group of 4a, leading to a favored rebound over desaturation. This steric demand may also be the reason for the decreased turnovers for substrate 4a compared to substrate 5a.

Interestingly, all substrates that show desaturation only gave byproducts from α-hydroxylation. Thus, for 2a, 4a, and 5a the α-hydroxylated product is a tertiary alcohol, and for 4a and 5a a benzylic alcohol. These products originate from the breaking of the weakest C–H bond in the molecule, which yields a stable radical. This implies that, for the α-hydroxylation and desaturation of the substrate, Cα–H abstraction is the common initial step in the mechanism. Interestingly, also CYPCla activates the α-position of all substrates but solely gives α-hydroxylation as products. Therefore, the desaturase activity by OleTJE and CYPBsβ might originate from an unfavorable oxygen-rebound step due to differences in substrate binding pockets (vide infra). Note that, in none of the cases studied, terminal side-chain hydroxylation, i.e., the formation of term-2d or term-4d (Scheme 1), occurred.

Enantioselectivity of OleTJE, CYPCla, or CYPBSβ

All tested CYP isozymes exhibit a slight stereochemical preference for the (R)-enantiomer of α-chiral substrates 2a–5a. Due to the large number of possible reaction pathways, the enantiomeric ratios (E-values) could not be calculated in most cases. As CYPCla did produce only one product, the system can be described using enantiomeric ratios: low E-values (<10) were calculated for substrates 2a–5a, based on the conversion and the substrates ee values. As the reaction of CYPBSβ with substrate 5a yields only one product (5d), and the substrate stereocenter is not altered throughout the reaction, this is the only other reaction that can be described with an enantiomeric ratio. A value of 30 was obtained. For the other reactions, high substrate conversion paired with high ee values (up to 99%) suggests moderate E-values. Substrate 2a, bearing the smallest substituents and therefore the least possible interactions for chiral recognition, gave the lowest ee values. A high stereoselectivity for the (R)-enantiomer (ee values of up to 99%) was obtained from β-hydroxylation of substrates 1a (by OleTJE and CYPBSβ) and 5a (by CYPBSβ), which matches previous observations with CYPBSβ.16c Similarly, α-hydroxylation of 4a by all enzymes produced (R)-4c with stereoselectivities of >95%. Interestingly, this result contrasts the reported selectivity of the CYP152 family member CYPSPα.34 The slightly less bulky substrates 2a, 3a, and 5a were found to be α-hydroxylated by all CYP isozymes with moderate to good ee values. Especially in the case of α-hydroxylation, the stereogenic center is destroyed throughout the reaction mechanism, and the selectivity of the rebound determines the stereochemical outcome. Interestingly, low ee values, paired with high conversion (e.g., CYPCla and 3a), suggest that the rebound can occur from both faces of the planar α-radical intermediate. It is worth mentioning that chiral tertiary alcohol moieties in the α-position of carboxylic acids represent attractive synthons, which are difficult to generate by conventional means.

Isotope Labeling Studies

Overall, the observed selectivity of substrate activation by the CYP isozymes OleTJE, CYPCla, and CYPBSβ is clearly dependent on the shape and size of the substrate and its positioning in the binding pocket. Most likely all reactions are initiated by hydrogen atom abstraction from either Cα or Cβ of the substrate. To determine the location of initial Cα–H abstraction for desaturation, regiospecifically deuterated derivatives [2-2H]-2a and [3,3-2H2]-2a of 2-methylbutyric acid (2a) were synthesized and used as substrate probes for the OleTJE/CamAB-FDH system (see the SI).

As expected, the introduction of the deuterium in the α- and β-position had severe effects on the outcome of product formation (Table 2). The decarboxylation reactivity was significantly reduced when the β,β-dideuterated substrate [3,3-2H2]-2a was applied, whereas it was slightly promoted with [2-2H]-2a. Similar isotope effects are found for the aromatic [2-2H]-4a (see Table S28, Supporting Information). This suggests Cβ–H-abstraction as the rate-limiting step for the decarboxylation. On the contrary, desaturation reactivity radically diminished with the α-deuterated [2-2H]-2a, and to a smaller extent, also for [3,3-2H2]-2a. Similarly, α-hydroxylation was reduced with the α-deuterated compound, whereas β-deuteration had only marginal effects on this reactivity. This leads to the conclusion that, for desaturation and α-hydroxylation, the rate-limiting hydrogen abstraction takes place at Cα, while Cβ has no impact in the α-hydroxylation and plays only a minor role in desaturation (being the second H that is abstracted). Even though regioselective deuteration is known to potentially alter the reaction center, no switch in regioselectivity toward β-hydroxylation was detectable. Potential additional hydride transfer steps could be ruled out by analysis of MS-fragmentation patterns.35

Table 2. Product Distributions of the Reaction of 2H-Labelled Substrates 2a with the OleTJE/CamAB–FDH System as Mechanistic Probesa.

Reaction performed on 500 μL scale for 24 h with OleTJE/CamAB–FDH system; see the SI. Conversion is given relative to the conversion obtained with 2a.

Ratio of formed product of 2a relative to the deuterated probe ([2-2H]-2a or [3,3-2H2]-2a) [concn(H):concn(D)].

Computation

To gain insight into the origin of the enantio- and regioselectivity of substrate activation by CYP OleTJE isozymes, a density functional theory study on the mechanisms leading to desaturation, α- and β-hydroxylation and decarboxylation of (R)- and (S)-2-methylbutyrate (2a) by the active iron(IV)-oxo heme cation radical species CYP Compound I (CpdI), was done.1,4,36 This system was studied extensively with computational methods and found to have close-lying doublet and quartet spin states.37 CpdI was characterized with spectroscopic methods for CYP119, including electron paramagnetic resonance studies and ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy.36

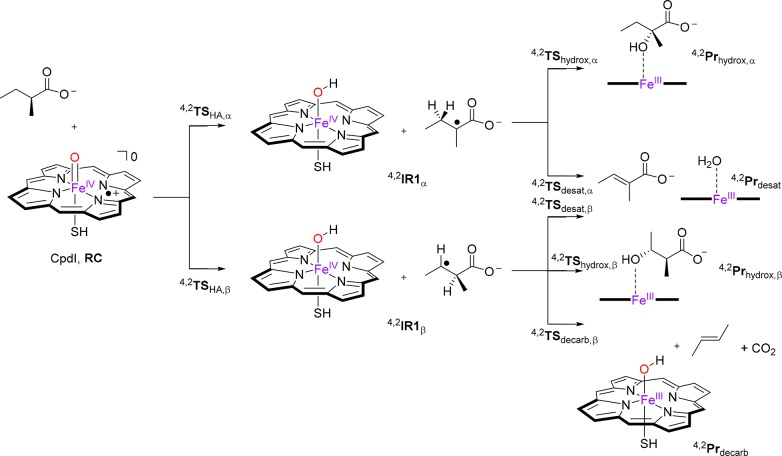

Two different active site models of CpdI with substrate (models A and B) were created, and the substrate activation according to the mechanisms in Figure 2 was studied. Focus was set on the large model (model B) as it contains the full shape of the substrate binding pocket and hence mimics the real protein better. In general, the absence of the substrate binding pocket residues leads to the lowering of reaction barriers and gives a preference of abstracting the weakest C–H bond. Details of the small model calculations are given in the SI. The reactions start from a reactant complex (RC) of CpdI with the substrate via an initial hydrogen atom abstraction from either Cα–H or Cβ–H via transition states TSHA,α and TSHA,β, respectively. Both systems relax to a radical intermediate consisting of an iron(IV)hydroxo-heme and a nearby radical (IR1α and IR1β; IR, intermediate representation). Past these radical intermediates the mechanisms bifurcate, and from IR1α the possibilities are α-oxygen-rebound via TShydrox,α to form α-hydroxylated product (Prhydrox,α) or alternatively hydrogen atom abstraction from Cβ via transition state TSdesat,α to give desaturation products (Prdesat). The mechanisms from IR1β lead to three possible products, namely, desaturation products (Prdesat) via a second hydrogen atom abstraction via transition state TSdesat,β, radical rebound to form β-hydroxylated products (Prhydrox,β) via transition state TShydrox,β, and finally decarboxylation via TSdecarb,β to give olefin, CO2, and an iron(III)-hydroxy-heme product (Prdecarb).

Figure 2.

Reaction mechanisms of (S)-2-methylbutyrate (2a) activation by a CYP CpdI model with definitions of the nomenclature. Protein residues of model B not shown.

The substrate enantiomers, i.e., (R)- and (S)-2-methylbutyrate [(R)-2a and (S)-2a], were docked into the crystal structure coordinates, and several low-energy conformations were found (Figures S5 and S6, see the SI for details). The geometries of the RC were optimized with DFT methods in the doublet and quartet spin states for three substrate (R)-conformers (R1, R4, and R7) and five (S)-conformers (S1, S2, S3, S5, and S6).

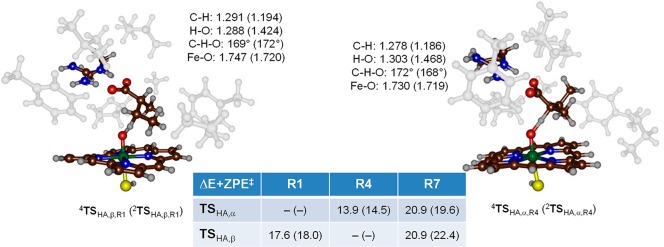

Subsequently, the hydrogen atom abstraction from the Cα–H and Cβ–H positions of the substrate was calculated for all eight RC configurations including (R)- and (S)-enantiomers in the doublet and quartet spin states. Although a possible total of 32 transition states were searched, a large number of those were high in energy and inaccessible due to the position of the substrate in the binding pocket. Particularly, the salt bridge between the substrates’ carboxylate and Arg245 residue gives considerable restraints to substrate rotation and makes some C–H groups inaccessible for the oxidant. Figure 3 gives the full set of hydrogen atom abstraction transition states located for all substrate binding positions of the (R)-enantiomer of 2-methylbutyrate (2a). For substrate binding in position R1, only β-hydrogen atom abstraction is found with activation energies of ΔE + ZPE⧧ = 17.6 (quartet) and 18.0 (doublet) kcal mol–1. On the other hand, binding orientation R4 only gives accessible Cα–H hydrogen atom abstraction with barriers of 13.9 (quartet) and 14.5 (doublet) kcal mol–1. Thus, even though the R4 reactant complexes are higher in energy by 2 kcal mol–1, their hydrogen atom abstraction barriers are lower. Structurally, hydrogen atom abstraction transition states 4,2TSHA,α,R4 and 4,2TSHA,β,R1 are alike with short C–H and long O–H distances in the low-spin and the hydrogen atom almost midway in between the donor and acceptor atoms in the high-spin. After the transition states, the complexes relax to a radical intermediate with configuration [FeIV(OH)(heme)SH]–Sub• through electron transfer from the substrate into the heme a2u orbital for both doublet and quartet spin states. Reaching the radical intermediates (4,2IR1α,R4 and 4,2IR1β,R1) is an almost thermoneutral process with values of −6.6/–6.6 and 1.2/1.1 kcal mol–1, respectively.

Figure 3.

Optimized transition states (4,2TSHA,α,R4 and 4,2TSHA,β,R1) for hydrogen atom abstraction of (R)-2-methylbutyrate (2a) by CYP OleTJE as calculated in Gaussian with doublet spin data in parentheses. Bond lengths are given in Å and angles in degrees. Energies of activation (in kcal mol–1 relative to 4RCR1) calculated at UB3LYP-GD3/BS3//UB3LYP-GD3/BS4 with solvent corrections included. Inaccessible (high-energy) pathways are identified with dashes (−).

The substrate binding orientation R7 is weaker than R1 and R4 as only one oxygen atom of the carboxylate is involved in the salt bridge with Arg245. However, this gives the substrate more flexibility, and now both pathways for Cα–H and Cβ–H hydrogen atom abstraction are accessible. All hydrogen atom abstraction transition states in the R7 conformation are high in energy, and the lowest one (2TSHA,α,R7) has an activation energy of 19.6 kcal mol–1. The hydrogen atom abstraction barriers in R7 stay high in energy compared to those found for R1.

All hydrogen atom abstraction pathways for the (S)-enantiomer [(S)-2a] of the substrate (Figure 4) were calculated. Although five substrate binding positions were identified, in only three of those viable hydrogen atom abstraction barriers were found. The lowest-energy hydrogen atom abstraction for (S)-2a by OleTJE CpdI is from the β-position in conformation S1 in the doublet spin state (2TSHA,β,S1) that gives an activation energy of only 10.3 kcal mol–1. This barrier is 3.6 kcal mol–1 lower in energy than the lowest hydrogen atom abstraction barrier for the (R)-enantiomer and would imply faster conversion of (S)-2a as compared to (R)-2a by OleTJE, which is experimentally confirmed.

Figure 4.

Optimized transition states (4,2TSHA,α,S1, 4,2TSHA,β,S1, 4,2TSHA,β,S2, and 4,2TSHA,α,S5) for hydrogen atom abstraction in (S)-2-methylbutyrate by CYP OleTJE as calculated in Gaussian with doublet spin data in parentheses. Bond lengths are given in Å and angles in degrees. Energies of activation (in kcal mol–1 relative to 4RCR1) calculated at UB3LYP-GD3/BS3//UB3LYP-GD3/BS4 with solvent corrections included. Inaccessible (high-energy) pathways are identified with dashes (−).

Within 4 kcal mol–1 of 2TSHA,β,S1 there are four more hydrogen atom abstraction barriers, namely, 4TSHA,β,S2 (ΔE + ZPE⧧ = 11.9 kcal mol–1), 2TSHA,α,S1 (ΔE + ZPE⧧ = 13.8 kcal mol–1), 2TSHA,β,S2 (ΔE + ZPE⧧ = 13.9 kcal mol–1), and 4TSHA,β,S1 (ΔE + ZPE⧧ = 14.3 kcal mol–1). Another three transition states are within 6 kcal mol–1 of 4TSHA,β,S2, see Figures 3 and 4.

In summary, (R)-2-methylbutyrate [(R)-2a] was found to bind preferentially in position R1, but the lowest-energy HAT pathway is for Cα–H abstraction in position R4; as such products resulting from Cα–H abstraction should be dominant. The (S)-isomer, by contrast, has close-lying S1 and S2 substrate binding positions that could give Cα–H and Cβ–H hydrogen atom abstraction pathways with lower barriers than those seen for the (R)-isomer. As such, theory predicts faster reactivity of (S)-2a over (R)-2a in agreement with the experimental turnover numbers (Table 1) that give preferential (S)-2a reactivity over (R)-2a. The computational work compares well with experiment and highlights the effect of substrate positioning and the shape and size of the substrate binding pocket on the regio- and chemoselectivity as also highlighted by the experimental results shown in Table 1. Technically, Cα–H hydrogen atom abstraction can lead to desaturation and α-hydroxylation products, whereas Cβ–H hydrogen atom abstraction can give β-hydroxylation, desaturation, and decarboxylation products. Although we did not test these pathways for all our isomeric structures and substrate binding positions, as an example we tested all five pathways for one specific isomer, namely, for (S)-2a bound in the S1 conformation as this structure gives accessible Cα–H and Cβ–H hydrogen atom abstraction pathways.

For the substrate bound in the S1-position, the full reaction mechanism leading to products was located. Thus, after hydrogen atom abstraction the complexes relax to an intermediate with a radical on Cα (with energies relative to 4,2RCS1 of −7.4 and −7.5 kcal mol–1 in the quartet and doublet spin state) or on Cβ (ΔE + ZPE = −0.9 and −1.1 kcal mol–1 in the quartet and doublet spin state). These relative energies correspond to the relative stability of a tertiary versus secondary carbon radical and favor hydrogen atom abstraction from Cα–H. The size and shape of the substrate binding pocket and oxidant and the rigidity of substrate binding thanks to the Arg245 salt bridge means that Cα–H reactivity is not necessarily the most dominant pathway as seen from the relative energies of the transition states in Figure 4. Subsequent reaction of the Cα-radical intermediate (4,2IRα,S1) leads to desaturation with a barrier of 2.8 (0.5) kcal mol–1 in the quartet (doublet) spin states, whereas the OH-rebound has a barrier of 3.2 kcal mol–1 (quartet spin state). By contrast, after the initial β-hydrogen atom abstraction, we calculated pathways for desaturation (2.8 kcal mol–1 on the quartet spin state), β-hydroxylation (3.0 kcal mol–1 on the doublet spin state), and decarboxylation (20.1 kcal mol–1 on the quartet spin state). Therefore, decarboxylation will be an inaccessible process here, and after β-hydrogen atom abstraction the only products expected will be for desaturation and β-hydroxylation. Previously, QM/MM calculations for arachidonic acid (C20) activation by CYP OleTJE gave decarboxylation barriers of <0.5 kcal mol–1 on the doublet spin state and 6.7–8.4 kcal mol–1 on the quartet spin state.14 Although the previous study uses different computational methods and techniques, the overall trends show that replacing arachidonic acid by methylbutyrate (2a) raises the decarboxylation barriers significantly as a lesser stable product is formed. This is in agreement with the data shown in Table 1, where for a long-chain fatty acid, as substrate 1a, decarboxylation is the dominant product, whereas for 2a desaturation is observed.

The calculations for the full mechanism for the conversion of reactants bound in conformation S1 to products predict dominant desaturation pathways for (S)-2a by CYP OleTJE via either 4,2IRα,S1 or 4,2IRβ,S1 pathways. In addition, the reaction channel that passes the 4,2IRα,S1 intermediate also gives α-hydroxylation products, whereas β-hydroxylation is accessible for 2IRβ,S1. Therefore, the computational studies are in excellent agreement with the product distributions reported above in Figure 1.

Rationalization of the Product Distributions

As shown in this work, product-types and distributions of the reaction of CYP OleTJE with substrates are highly dependent on the type of substrate chosen: Linear fatty acids, such as myristic acid (1a), are converted by CYP OleTJE to terminal olefins and β-hydroxylation products. By contrast, 2-phenylbutyric acid (3a) also gives decarboxylation to form a terminal olefin, but as side product α-hydroxylation (rather than β-hydroxylation) is seen. Finally, 2-methylbutyric acid (2a) reacts via desaturation (rather than decarboxylation) alongside α-hydroxylation pathways. The diverse substrate activation by CYP OleTJE is rationalized as follows.

As shown in the past, the reaction rate for hydrogen atom abstraction reactions often correlates with the bond dissociation energy (BDE) of the C–H bond that is broken during the reaction.4c,29,38 Thus, for a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reaction between CpdI or [FeIV(O)(heme+•)Cys], and a substrate (Sub–H), the general equation for HAT as shown in eq 1 can be formulated. The driving force for that reaction is dependent on the difference in energy of the BDECH of the substrate and the BDEOH of the iron(IV)-hydroxo complex, eq 2.39

| 1 |

| 2 |

The bond dissociation energies of the Cα–H and Cβ–H bonds of 2-methylbutyric acid (2a) are defined as BDECα–H and BDECβ–H. Their values were calculated at UB3LYP/6-31G* level of theory with dispersion, solvent, and zero-point corrections and give BDECα–H = 83.5 and BDECβ–H = 94.1 kcal mol–1, respectively. Therefore, α-HAT should be significantly preferred over β-HAT in a reaction of CYP Compound I with 2a under ideal circumstances, i.e., without substrate perturbations by the protein pocket. Together with the BDEOH of the iron(IV)-hydroxo complex of 90.8 kcal mol–1 α-HAT and β-HAT are (based on eq 2) ΔE = −7.3 and +3.3 kcal mol–1. These values match the energies to reach the radical intermediates excellently, e.g., compare with Supporting Information, Table S15.

Figure 5 gives the orbital and electron distributions during the hydrogen atom abstraction step. Thus, CpdI has a biradical along the Fe–O bond due to orbital occupation of the antibonding π*xz and π*yz orbitals with one electron. In addition, there is a heme radical (in a2u) to give a ferromagnetic quartet or antiferromagnetic doublet spin state.4b,37,40 Upon hydrogen atom abstraction from either Cα–H or Cβ–H these bonds break, and a radical remains on the substrate rest-group designated ϕRα and ϕRβ. The hydrogen atom forms a bond with the oxo group (σOH), and as a result, the πxz/π*xz pair of orbitals breaks and moves one electron into a2u.

Figure 5.

VB depiction of hydrogen atom abstraction from the α- or β-position of 2-methylbutyric acid (2a) with orbital changes highlighted and HAT driving forces in kcal mol–1 (also given for 1a and 3a). Dots represent valence electrons, and a line in between two dots represents a bonding orbital occupied by two electrons.

To understand the relative barriers, valence bond (VB) modeling was used to predict the hydrogen atom abstraction barriers from empirical relationships as described and explained previously.41 In particular, a model was devised, based on the vertical energy (Gexc) difference between the reactant and product configuration in the geometry of the reactants plus a component for the driving force (ΔErp) from reactants to products as described by eq 3 and were derived previously.41c Previously, these electronic structure analyses were used to rationalize regioselectivities and substrate activation trends by various iron(IV)-oxo intermediates. To explore whether here also electronic factors contribute to rebound versus desaturation versus decarboxylation processes, we used these VB models to explore the regioselectivities. The reorganization energy B is included for the change in structure during the reaction coordinate and is taken as half the value of the weakest of the bonds that are either broken or formed.

| 3 |

For the hydrogen atom transfer, the driving force is simply the difference in energy between the BDECH and BDEOH as described by eq 2 above. The value of Gexc contains contributions for bond breaking and electron transfer processes that happen in the reaction step. Thus, as shown by the VB structures in Figure 5 during the hydrogen atom abstraction step, one C–H bond from the substrate is broken (BDECα–H or BDECβ–H), but on top of that also the πxz/π*xz three-electron bond reverts to atomic orbitals. The contribution from this was estimated previously as 136.0 kcal mol–1.42 As such eq 3 predicts a hydrogen atom abstraction barrier from the Cα–H and Cβ–H positions of 2a of 7.6 and 14.6 kcal mol–1 (Figure 5). These values are in good quantitative agreement with the small model complex calculations. However, the addition of the substrate binding pocket (Figures 3 and 4) raises these values significantly and particularly makes these two pathways competitive. These barriers were also predicted for myristic acid (1a) and 2-phenylbutyric acid (3a).

In all three substrates, the hydrogen atom abstraction barrier from Cβ–H is similar (Figure 5), but dramatically different on Cα. The BDECα–H of 3a is very small (79.3 kcal mol–1) and consequently well-separated from that of Cβ–H. The VB modeling, therefore, predicts dominant products originating from Cα–H hydrogen atom abstraction for substrate 3a, which is observed experimentally (Figure 1). For substrate 1a the smallest hydrogen atom abstraction difference between Cα–H and Cβ–H is found from VB modeling. Indeed, this substrate gives mostly reaction products originating from Cβ–H abstraction by CpdI (Figure 1).

Subsequently, the pathways from the radical intermediates (4,2IR1α and 4,2IR1β) were analyzed, leading to α- and β-hydroxylation, desaturation, and decarboxylation, which are described through the VB analysis in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

VB mechanism for reaction pathways leading to desaturation, hydroxylation, and decarboxylation from radical intermediates during the reaction of CpdI with 2a.

From the intermediates 4,2IR1α the OH-rebound pathway gives 2-hydroxy-2-methylbutyric acid (2c) by forming a σCO bond between the radical and OH groups. At the same time the πyz/π*yz three-electron bond reverts to atomic orbitals, whereby one electron moves into the σCO orbital, and the other two remain on iron. A similar mechanism is found for the desaturation pathway from 4,2IR1β. Therefore, the desaturation energy (Edesat,α) from 4,2IR1α contains contributions for the breaking of the σCH orbital of Cβ—H (BDErad,β), the energy to break the πyz/π*yz orbitals (Eπ/π*yz), and the forming of the π-bond of the olefin (EπR). These contributions were estimated from small model complexes, and a desaturation barrier from 4,2IRα of 1.6 kcal mol–1 was predicted, whereas it is 3.1 kcal mol–1 from 4,2IRβ. These values are in good agreement with the DFT results presented above. For the radical rebound process, the iron(IV)-hydroxo changes to an iron(III)(heme) weakly coordinating to an alcohol or water molecule. This means that again the πyz/π*yz orbitals break along the Fe—O bond. On top of that, the radical undergoes major structural changes as the radical center changes from sp2 to sp3 hybridization upon OH-rebound, and the radical loses its conjugation with the C=O π-bond. An estimation of this conjugation loss to about 70 kcal mol–1 raises the VB predicted rebound barriers above the desaturation barriers in energy.

In summary, the product ratios of desaturation versus α- and β-hydroxylation are dependent on the strength of the σCO orbital formed after rebound versus the difference of the strength of the π-bond in the olefin formed and the loss of conjugation energy of the radical with the carboxylate π-bond. These energy contributions are dependent on the nature of the substrate, and hence different products are obtained for substrates 1a, 2a, and 3a.

Conclusion

Overall, this work provides a detailed insight into the stereoselectivity and reactivity patterns of CYP OleTJE and the CYP152 family in general. The enzymes’ biotechnological importance arises from their ability to use H2O2 as an oxidant and to convert fatty acids into valuable products via oxidative decarboxylation and α- or β-hydroxylation. In this work, we show a novel reaction pathway leading to α,β-desaturation of carboxylic acids. All reactivities were investigated with selectively deuterated substrate probes, revealing the rate-limiting steps. Linear fatty acids generally react with CYP OleTJE by hydrogen atom abstraction from the β-position leading to decarboxylation products. The α,β-desaturase activity reported here is initiated by hydrogen atom abstraction from Cα–H, which is supported by the observation that the desaturation activity often is accompanied by α-hydroxylation. The latter is preferred with substrates bearing an activated Cα and is supported by the strong isotope effect on the desaturation activity.

The product distributions were rationalized with computational studies which revealed that the reactivity highly depends on substrate positioning and involves the carbon with the lowest hydrogen abstraction barrier. Therefore, a weaker Cα–H bond initiates α-hydroxylation and desaturation, and a weaker Cβ–H bond leads to β-hydroxylation and oxidative decarboxylation.

Acknowledgments

Funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) within the DK Molecular Enzymology (project W901) is gratefully acknowledged. This work has been supported by the Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs (bmwd), the Federal Ministry for Transport, Innovation and Technology (bmvit), the Styrian Business Promotion Agency SFG, the Standortagentur Tirol, Government of Lower Austria and ZIT—Technology Agency of the City of Vienna through the COMET-Funding Program managed by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG. The funding agencies had no influence on the conduct of this research. F.G.C.R. thanks the Conacyt Mexico for a studentship. S.d.V. thanks the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) for funding under grant code BB/N006275/1.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscatal.8b03733.

Protein production and purification procedures, chiral and achiral GC- and HPLC-analytics and chromatograms, MS fragmentation patterns, synthetic procedures for substrates and reference compounds including NMR spectra, preparation and characterization of regioselectively deuterated mechanistic probes, control reactions for the verification of enzymatic desaturation, computational methods and data in absolute and relative energies, group spin densities, and charges, and Cartesian coordinates of optimized geometries (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ M.P. and S.K. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Sono M.; Roach M. P.; Coulter E. D.; Dawson J. H. Heme-Containing Oxygenases. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 2841–2888. 10.1021/cr9500500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Meunier B.; de Visser S. P.; Shaik S. Mechanism of Oxidation Reactions Catalyzed by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3947–3980. 10.1021/cr020443g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Denisov I. G.; Makris T. M.; Sligar S. G.; Schlichting I. Structure and Chemistry of Cytochrome P450. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2253–2277. 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ortiz de Montellano P. R., Ed.; Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism and Biochemistry, 3rd ed.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]; e Ortiz de Montellano P. R. Hydrocarbon Hydroxylation by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 932–948. 10.1021/cr9002193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Grogan G. Cytochromes P450: Exploiting Diversity and Enabling Application as Biocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011, 15, 241–248. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Fasan R. Tuning P450 Enzymes as Oxidation Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 647–666. 10.1021/cs300001x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Poulos T. L. Heme Enzyme Structure and Function. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3919–3962. 10.1021/cr400415k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Huang X.; Groves J. T. Oxygen Activation and Radical Transformations in Heme Proteins and Metalloporphyrins. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2491–2553. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Guengerich F. P. Common and Uncommon Cytochrome P450 Reactions Related to Metabolism and Chemical Toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001, 14, 611–650. 10.1021/tx0002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Posner G. H.; O’Neill P. M. Knowledge of the Proposed Chemical Mechanism of Action and Cytochrome P450 Metabolism of Antimalarial Trioxanes Like Artemisinin Allows Rational Design of New Antimalarial Peroxides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 397–404. 10.1021/ar020227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Groves J. T.Models and Mechanisms of Cytochrome P450 Action. In Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism and Biochemistry, 3rd ed.; Ortiz de Montellano P. R., Ed.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, 2005; Chapter 1, pp 1–44. [Google Scholar]; b Nam W. High-Valent Iron(IV)–Oxo Complexes of Heme and Non-Heme Ligands in Oxygenation Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 522–531. 10.1021/ar700027f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Watanabe Y.; Nakajima H.; Ueno T. Reactivities of Oxo and Peroxo Intermediates Studied by Hemoprotein Mutants. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 554–562. 10.1021/ar600046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Dawson J. H.; Sono M. Cytochrome P-450 and Chloroperoxidase: Thiolate-Ligated Heme Enzymes. Spectroscopic Determination of their Active-Site Structures and Mechanistic Implications of Thiolate Ligation. Chem. Rev. 1987, 87, 1255–1276. 10.1021/cr00081a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Shaik S.; Kumar D.; de Visser S. P.; Altun A.; Thiel W. Theoretical Perspective on the Structure and Mechanism of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2279–2328. 10.1021/cr030722j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Shaik S.; Cohen S.; Wang V.; Chen H.; Kumar F.; Thiel W. P450 Enzymes: Their Structure, Reactivity, and Selectivity - Modeled by QM/MM Calculations. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 949–1017. 10.1021/cr900121s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Whitehouse C. J. C.; Bell S. G.; Wong L.-L. P450BM3(CYP102A1): Connecting the Dots. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1218–1260. 10.1039/C1CS15192D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold F. H. Directed Evolution: Bringing New Chemistry to Life. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4143–4148. 10.1002/anie.201708408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kan S. B. J.; Huang X.; Gumulya Y.; Chen K.; Arnold F. H. Genetically Programmed Chiral Organoborane Synthesis. Nature 2017, 552, 132–136. 10.1038/nature24996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kan S. B. J.; Lewis R. D.; Chen K.; Arnold F. H. Directed Evolution of Cytochrome C for Carbon–Silicon Bond Formation: Bringing Silicon to Life. Science 2016, 354, 1048–1052. 10.1126/science.aah6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c McIntosh J. A.; Coelho P. S.; Farwell C. C.; Wang Z. J.; Lewis J. C.; Brown T. R.; Arnold F. H. Enantioselective Intramolecular C-H Amination Catalyzed by Engineered Cytochrome P450 Enzymes In Vitro and In Vivo. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9309–9312. 10.1002/anie.201304401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Singh R.; Bordeaux M.; Fasan R. P450-Catalyzed Intramolecular sp3 C–H Amination with Arylsulfonyl Azide Substrates. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 546–552. 10.1021/cs400893n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Prier C. K.; Zhang R. K.; Buller A. R.; Brinkmann-Chen S.; Arnold F. H. Enantioselective, Intermolecular Benzylic C-H Amination Catalysed by an Engineered Iron-Haem Enzyme. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 629–634. 10.1038/nchem.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Coelho P. S.; Brustad E. M.; Kannan A.; Arnold F. H. Olefin Cyclopropanation via Carbene Transfer Catalyzed by Engineered Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Science 2013, 339, 307–310. 10.1126/science.1231434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Knight A. M.; Kan S. B. J.; Lewis R. D.; Brandenberg O. F.; Chen K.; Arnold F. H. Diverse Engineered Heme Proteins Enable Stereodivergent Cyclopropanation of Unactivated Alkenes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 372–377. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Giovani S.; Alwaseem H.; Fasan R. Aldehyde and Ketone Synthesis by P450-Catalyzed Oxidative Deamination of Alkyl Azides. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 2609–2613. 10.1002/cctc.201600487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Puchkaev A. V.; Ortiz de Montellano P. R. The Sulfolobus Solfataricus Electron Donor Partners of Rhermophilic CYP119: An Unusual Non-NAD(P)H-Dependent Cytochrome P450 System. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 434, 169–177. 10.1016/j.abb.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mandai T.; Fujiwara S.; Imaoka S. A Novel Electron Transport System for Thermostable CYP175A1 from Thermus Thermophilus HB27. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 2416–2429. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Shoji O.; Fujishiro T.; Nagano S.; Tanaka S.; Hirose T.; Shiro Y.; Watanabe Y. Understanding Substrate Misrecognition of Hydrogen Peroxide Dependent Cytochrome P450 from Bacillus Subtilis. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 15, 1331–1339. 10.1007/s00775-010-0692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shoji O.; Watanabe Y. Peroxygenase Reactions Catalyzed by Cytochromes P450. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 19, 529–539. 10.1007/s00775-014-1106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang Y.; Lan D.; Durrani R.; Hollmann F. Peroxygenases En Route to Becoming Dream Catalysts. What are the Opportunities and Challenges?. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 37, 1–9. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wise C. E.; Hsieh C. H.; Poplin N. L.; Makris T. M. Dioxygen Activation by the Biofuel-Generating Cytochrome P450 OleT. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9342–9352. 10.1021/acscatal.8b02631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Munro A. W.; McLean K. J.; Grant J. L.; Makris T. M. Structure and Function of the Cytochrome P450 Peroxygenase Enzymes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 183–196. 10.1042/BST20170218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Belcher J.; McLean K. J.; Matthews S.; Woodward L. S.; Fisher K.; Rigby S. E. J.; Nelson D. R.; Potts D.; Baynham M. T.; Parker D. A.; Leys D.; Munro A. W. Structure and Biochemical Properties of the Alkene Producing Cytochrome P450 OleTJE (CYP152l1) from the Jeotgalicoccus Sp. 8456 bacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 6535–6550. 10.1074/jbc.M113.527325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Amaya J. A.; Rutland C. D.; Makris T. M. Mixed Regiospecificity Compromises Alkene Synthesis by a Cytochrome P450 Peroxygenase from Methylobacterium Populi. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 158, 11–16. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Rude M. A.; Baron T. S.; Brubaker S.; Alibhai M.; Del Cardayre S. B.; Schirmer A. Terminal Olefin (1-Alkene) Biosynthesis by a Novel P450 Fatty Acid Decarboxylase from Jeotgalicoccus Species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1718–1727. 10.1128/AEM.02580-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu Y.; Wang C.; Yan J.; Zhang W.; Guan W.; Lu X.; Li S. Hydrogen Peroxide-Independent Production of α-Alkenes by OleTJE P450 Fatty Acid Decarboxylase. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2014, 7, 28–40. 10.1186/1754-6834-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dennig A.; Kuhn M.; Tassoti S.; Thiessenhusen A.; Gilch S.; Bülter T.; Haas T.; Hall M.; Faber K. Oxidative Decarboxylation of Short-Chain Fatty Acids to 1-Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 8819–8822. 10.1002/anie.201502925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Matthews S.; Belcher J. D.; Tee K. L.; Girvan H. M.; McLean K. J.; Rigby S. E.; Levy C. W.; Leys D.; Munro A. W. Catalytic Determinants of Alkene Production by the Cytochrome P450 Peroxygenase OleT JE. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 5128–5143. 10.1074/jbc.M116.762336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Belcher J.; McLean K. J.; Matthews S.; Woodward L. S.; Fisher K.; Rigby S. E. J.; Nelson D. R.; Potts D.; Baynham M. T.; Parker D. A.; Leys D.; Munro A. W. Structure and Biochemical Properties of the Alkene Producing Cytochrome P450 OleTJE(CYP152L1) from the Jeotgalicoccus Sp. 8456 Bacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 6535–6550. 10.1074/jbc.M113.527325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Grant J. L.; Hsieh C. H.; Makris T. M. Decarboxylation of Fatty Acids to Terminal Alkenes by Cytochrome P450 Compound I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4940–4943. 10.1021/jacs.5b01965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Grant J. L.; Mitchell M. E.; Makris T. M. Catalytic Strategy for Carbon–Carbon Bond Scission by the Cytochrome P450 OleT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 10049–10054. 10.1073/pnas.1606294113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hsieh C. H.; Huang X.; Amaya J. A.; Rutland C. D.; Keys C. L.; Groves J. T.; Austin R. N.; Makris T. M. The Enigmatic P450 Decarboxylase OleT is Capable of, but Evolved to Frustrate, Oxygen Rebound Chemistry. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 3347–3357. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Amaya J. A.; Rutland C. D.; Leschinsky N.; Makris T. M. A Distal Loop Controls Product Release and Chemo- and Regioselectivity in Cytochrome P450 Decarboxylases. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 344–353. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Matsunaga I.; Ueda A.; Sumimoto T.; Ichihara K.; Ayata M.; Ogura H. Site-Directed Mutagenesis of the Putative Distal Helix of Peroxygenase Cytochrome P450. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 394, 45–53. 10.1006/abbi.2001.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lee D.-S.; Yamada A.; Sugimoto H.; Matsunaga I.; Ogura H.; Ichihara K.; Adachi S.; Park S.-Y.; Shiro Y. Substrate Recognition and Molecular Mechanism of Fatty Acid Hydroxylation by Cytochrome P450 from Bacillus Subtilis: Crystallographic, Spectroscopic, and Mutational Studies. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 9761–9767. 10.1074/jbc.M211575200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang J.; Lonsdale R.; Reetz M. T. Exploring Substrate Scope and Stereoselectivity of P450 Peroxygenase OleTJE in Olefin-Forming Oxidative Decarboxylation. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 8131–8133. 10.1039/C6CC04345C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lu C.; Shen F.; Wang S.; Wang Y.; Liu J.; Bai W.; Wang X. An Engineered Self-sufficient Biocatalyst Enables Scalable Production of Linear Alpha Olefins from Carboxylic Acids. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5794–5798. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faponle A. S.; Quesne M. G.; de Visser S. P. Origin of the Regioselective Fatty-Acid Hydroxylation versus Decarboxylation by a Cytochrome P450 Peroxygenase: What Drives the Reaction to Biofuel Production?. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 5478–5483. 10.1002/chem.201600739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girhard M.; Schuster S.; Dietrich M.; Dürre P.; Urlacher V. B. Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase from Clostridium Acetobutylicum: A new α-Fatty Acid Hydroxylase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 362, 114–119. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Shoji O.; Fujishiro T.; Nakajima H.; Kim M.; Nagano S.; Shiro Y.; Watanabe Y. Hydrogen Peroxide Dependent Monooxygenations by Tricking the Substrate Recognition of Cytochrome P450BSβ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3656–3659. 10.1002/anie.200700068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fujishiro T.; Shoji O.; Nagano S.; Sugimoto H.; Shiro Y.; Watanabe Y. Crystal Structure of H2O2-dependent Cytochrome P450SPα with its Bound Fatty Acid Substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 29941–29950. 10.1074/jbc.M111.245225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Matsunaga I.; Ueda A.; Fujiwara N.; Sumimoto T.; Ichihara K. Characterization of the ybdT Gene Product of Bacillus Subtilis: Novel Fatty Acid β-Hydroxylating Cytochrome P450. Lipids 1999, 34, 841–846. 10.1007/s11745-999-0431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a de Visser S. P.; Quesne M. G.; Martin B.; Comba P.; Ryde U. Computational Modelling of Oxygenation Processes in Enzymes and Biomimetic Model Complexes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 262–282. 10.1039/C3CC47148A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Quesne M. G.; Borowski T.; de Visser S. P. Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics Modelling of Enzymatic Processes: Caveats and Breakthroughs. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 2562–2581. 10.1002/chem.201503802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Becke A. D. Density-Functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula Into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francl M. M.; Pietro W. J.; Hehre W. J.; Binkley J. S.; Gordon M. S.; DeFrees D. J.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XXIII. A Polarization-Type Basis Set for Second-Row Elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 3654–3658. 10.1063/1.444267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hay P. J.; Wadt W. R. Ab Initio Effective Core Potentials for Molecular Calculations. Potentials for the Transition Metal Atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 270–283. 10.1063/1.448799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Cross J. B.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann R. E.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Voth G. A.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels A. D.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Ortiz J. V.; Cioslowski J.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 09, revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- a Blomberg M. R. A.; Borowski T.; Himo F.; Liao R.-Z.; Siegbahn P. E. M. Quantum chemical studies of mechanisms for metalloenzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3601–3658. 10.1021/cr400388t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li D.; Wang Y.; Han K. Recent density functional theory model calculations of drug metabolism by cytochrome P450. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 1137–1150. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Liao R.-Z.; Yu J.-G.; Himo F. Quantum Chemical Modeling of Enzymatic Reactions: The Case of Decarboxylation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 1494–1501. 10.1021/ct200031t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liao R.-Z.; Thiel W. Comparison of QM-Only and QM/MM Models for the Mechanism of Tungsten-Dependent Acetylene Hydratase. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3793–3803. 10.1021/ct3000684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosdidier A.; Zoete V.; Michielin O. SwissDock, a Protein-Small Molecule Docking Web Service Based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W270–W277. 10.1093/nar/gkr366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A.; Horn H.; Ahlrichs R. Fully Optimized Contracted Gaussian Basis Sets for Atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. 10.1063/1.463096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schallmey A.; Den Besten G.; Teune I. G. P.; Kembaren R. F.; Janssen D. B. Characterization of Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase CYP154H1 from the Thermophilic Soil Bacterium Thermobifida Fusca. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 1475–1485. 10.1007/s00253-010-2965-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews S.; Tee K. L.; Rattray N. J.; McLean K. J.; Leys D.; Parker D. A.; Blankley R. T.; Munro A. W. Production of Alkenes and Novel Secondary Products by P450 OleTJE Using Novel H2O2-Generating Fusion Protein Systems. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 737–750. 10.1002/1873-3468.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydroxylation proceeds with retention of configuration between C–H and C–OH; switch is due to change in CIP priority.

- a Mayer J. M. PROTON-COUPLED ELECTRON TRANSFER: A Reaction Chemist’s View. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2004, 55, 363–390. 10.1146/annurev.physchem.55.091602.094446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b de Visser S. P. Trends in Substrate Hydroxylation Reactions by Heme and Nonheme Iron(IV)-Oxo Oxidants Give Correlations between Intrinsic Properties of the Oxidant with Barrier Height. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1087–1097. 10.1021/ja908340j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hammerer L.; Winkler C. K.; Kroutil W. Regioselective Biocatalytic Hydroxylation of Fatty Acids by Cytochrome P450s. Catal. Lett. 2018, 148, 787–812. 10.1007/s10562-017-2273-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Rettie A. E.; Rettenmeier A. W.; Howald W. N.; Baillie T. A. Cytochrome P450-Catalyzed Formation of delta 4-VPA, a Toxic Metabolite of Valproic Acid. Science 1987, 235, 890–893. 10.1126/science.3101178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kelly S. L.; Lamb D. C.; Kelly D. E. Sterol 22-Desaturase, Cytochrome P45061, Possesses Activity in Xenobiotic Metabolism. FEBS Lett. 1997, 412, 233–235. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00785-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Guan X. M.; Fisher M. B.; Lang D. H.; Zheng Y. M.; Koop D. R.; Rettie A. E. Cytochrome P450-Dependent Desaturation of Lauric Acid: Isoform Selectivity and Mechanism of Formation of 11-Dodecanoic Acid. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 1998, 110, 103–121. 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Guengerich F. P. Cytochrome P450 and Chemical Toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 70–83. 10.1021/tx700079z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Obach R. S. Mechanism of Cytochrome P4503A4- and 2D6-Catalyzed Dehydrogenation of Ezlopitant as Probed with Isotope Effects using Five Deuterated Analogs. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001, 29 (12), 1599–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Whitehouse C. J. C.; Bell S. G.; Wong L. L. Desaturation of Alkylbenzenes by Cytochrome P450BM3(CYP102A1). Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14, 10905–10908. 10.1002/chem.200801927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L.; Faponle A. S.; Quesne M. G.; Sainna M. A.; Zhang J.; Franke A.; Kumar D.; van Eldik R.; Liu W.; de Visser S. P. Drug Metabolism by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes: What Distinguishes the Pathways Leading to Substrate Hydroxylation Over Desaturation?. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9083–9092. 10.1002/chem.201500329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennig A.; Kurakin S.; Kuhn M.; Dordic A.; Hall M.; Faber K. Enzymatic Oxidative Tandem Decarboxylation of Dioic Acids to Terminal Dienes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 3473–3477. 10.1002/ejoc.201600358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga I.; Sumimoto T.; Kusunose E.; Ichihara K. Phytanic Acid α–Hydroxylation by Bacterial Cytochrome P450. Lipids 1998, 33, 1213–1216. 10.1007/s11745-998-0325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham N. P.; Chang W.-C.; Mitchell A. W.; Martinie R. J.; Zhang B.; Bergman J. A.; Rajakovich L. J.; Wang B.; Silakov A.; Krebs C.; Boal A. K.; Bollinger J. M. Two Distinct Mechanisms for C–C Desaturation by Iron(II)- and 2-(Oxo)glutarate-Dependent Oxygenases: Importance of α–Heteroatom Assistance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7116–7126. 10.1021/jacs.8b01933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittle J.; Green M. T. Cytochrome P450 Compound I: Capture, Characterization, and C-H Bond Activation Kinetics. Science 2010, 330, 933–937. 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ogliaro F.; Harris N.; Cohen S.; Filatov M.; de Visser S. P.; Shaik S. A Model “Rebound” Mechanism of Hydroxylation by Cytochrome P450: Stepwise and Effectively Concerted Pathways, and Their Reactivity Patterns. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8977–8989. 10.1021/ja991878x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kamachi T.; Yoshizawa K. A Theoretical Study on the Mechanism of Camphor Hydroxylation by Compound I of Cytochrome P450. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4652–4661. 10.1021/ja0208862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Bathelt C. M.; Zurek J.; Mulholland A. J.; Harvey J. N. Electronic Structure of Compound I in Human Isoforms of Cytochrome P450 from QM/MM Modelling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12900–12908. 10.1021/ja0520924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Schöneboom J. C.; Neese F.; Thiel W. Toward Identification of the Compound I Reactive Intermediate in Cytochrome P450 Chemistry: A QM/MM Study of Its EPR and Mössbauer Parameters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5840–5853. 10.1021/ja0424732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Li D.; Wang Y.; Han K. Recent Density Functional Theory Model Calculations of Drug Metabolism by Cytochrome P450. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 1137–1150. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su P.; Song L.; Wu W.; Hiberty P. C.; Shaik S. Valence Bond Calculations of Hydrogen Transfer Reactions: A General Predictive Pattern Derived from Theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13539–13549. 10.1021/ja048105f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Friedrich L. E. The Two Hydrogen-Oxygen Bond-Dissociation Energies of Hydroquinone. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 3851–3852. 10.1021/jo00169a062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Bordwell F. G.; Cheng J.-P. Substituent Effects on the Stabilities of Phenoxyl Radicals and the Acidities of Phenoxyl Radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1736–1743. 10.1021/ja00005a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Mayer J. M. Hydrogen Atom Abstraction by Metal–Oxo Complexes: Understanding the Analogy with Organic Radical Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998, 31, 441–450. 10.1021/ar970171h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. First-Principles Quantum Chemical Studies of Porphyrins. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998, 31, 189–198. 10.1021/ar950033x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Shaik S. S. What Happens to Molecules as They React? A Valence Bond Approach to Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 3692–3701. 10.1021/ja00403a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Shaik S. Valence Bond All the Way: From the Degenerate H-Exchange to Cytochrome P450. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 8706–8720. 10.1039/c001372m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cantú Reinhard F. G.; Sainna M. A.; Upadhyay P.; Balan G. A.; Kumar D.; Fornarini S.; Crestoni M. E.; de Visser S. P. A Systematic Account on Aromatic Hydroxylation by a Cytochrome P450 Model Compound I: A Low-Pressure Mass Spectrometry and Computational Study. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 18608–18619. 10.1002/chem.201604361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Cantú Reinhard F. G.; de Visser S. P. Oxygen Atom Transfer Using an Iron(IV)-Oxo Embedded in a Tetracyclic N-Heterocyclic Carbene System: How Does the Reactivity Compare to Cytochrome P450 Compound I?. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 2935–2944. 10.1002/chem.201605505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kaczmarek M. A.; Malhotra A.; Balan G. A.; Timmins A.; de Visser S. P. Nitrogen Reduction to Ammonia on a Biomimetic Mononuclear Iron Centre: Insights into the Nitrogenase Enzyme. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 5293–5302. 10.1002/chem.201704688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.-X.; Postils V.; Sun W.; Faponle A. S.; Solà M.; Wang Y.; Nam W.; de Visser S. P. Reactivity Patterns of (Protonated) Compound II and Compound I of Cytochrome P450: Which is the Better Oxidant?. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 6406–6418. 10.1002/chem.201700363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.