Abstract

Background:

Patients with cognitive impairment or dementias of uncertain etiology are frequently referred to a memory disorders specialty clinic. The impact of and role for amyloid PET imaging (Aβ-PET) may be most appropriate in this clinical setting.

Objective:

The primary objective of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of Aβ-PET on etiological diagnosis and clinical management in the memory clinic setting.

Methods:

A search of the literature on the impact of Aβ-PET in the memory clinic setting between 1 January 2004 and 12 February 2018 was conducted. Meta-analysis using a random effects model was performed to determine the pooled estimate of the impact of Aβ-PET in the changes of diagnoses and changes in management plan.

Results:

After rigorous review, results from 13 studies were extracted, involving 1,489 patients. Meta-analysis revealed a pooled effect of change in diagnoses of 35.2% (95% CI 24.6–47.5). Sub-analyses showed that the pooled effect in change in diagnoses if Aβ-PET was used under the appropriate use criteria (AUC) or non-AUC criteria were 47.8% (95% CI 25.9–70.5) and 29.6% (95% CI: 21.5–39.3), respectively. The pooled effect of a change of diagnosis from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to non-AD and from non-AD to AD were 22.7% (95% CI: 17.1–29.5) and 25.6% (95% CI: 17.6–35.8), respectively. The pooled effect leading to a change of management was 59.6% (95% CI 39.4–77.0).

Conclusions:

Aβ-PET has a highly significant impact on both changes in diagnosis and management among patients being seen at a specialty memory clinic.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid imaging, diagnosis, management, memory clinic, positron emission tomography

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60% of alldementia cases [1]. In the past, the gold standard in diagnosis was by postmortem histopathological examination of the brain. These examinations revealed some major limitations in accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of AD; compared with postmortem examination, a clinical diagnosis of probable AD had sensitivity and specificity of 70.9% and 70.8%, respectively [2]. In patients with a clinical diagnosis of non-AD dementia, 39% were found to have AD pathologies on postmortem examination. In addition, up to 25% of patients with probable AD had limited amyloid pathology on postmortem examination [3].Currently, with the use of amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging (Aβ-PET) or measurement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of amyloid-β(Aβ) 42, in vivo status of amyloid deposition can be determined prior to autopsy [4]. However, lumbar puncture to obtain CSF for Aβ42 measurement is invasive and Aβ-PET is more widely acceptable to patients. Current PET amyloid tracers in clinical use include: 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) and various 18F-labelled ligands, including the 18F-florbetaben (NeuraCeq, Piramal), 18F-florbetapir (Amyvid, Eli Lilly), and 18F-flutametamol (Vizamyl, GE Healthcare) [5].

18F-labeled tracers have a 110-min half-life allowing incorporation of PET into routine clinical practice [5]. Studies on histopathology-to-PET correlation have been published for these 18F-labelled ligands [6–12]. Clinicians in memory clinics often see patients with complicated histories, atypical clinical courses, rapid cognitive decline, or inconclusive investigational results. Aβ-PET has a role in these clinical situations. Appropriate use criteria (AUC) were published in 2013 to guide and optimize the utility of Aβ-PET [5]. Memory clinics, managed by dementia specialists, remain the best place to initially test the clinical impact of Aβ-PET in a real-world setting. Despite the absence of effective disease modifying therapies, an accurate diagnosis of dementia subtypes can lead to starting of necessary treatments, stopping of unnecessary treatments, avoiding unnecessary or inappropriate investigations, clarifying the queries of primary caregivers, and educating patients and/or caregivers to plan for the future, so as to ensure a better quality of life for all concerned. The prognostic information of a positive Aβ-PET in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), indicating likely progression to AD, can influence future treatment decisions, including consideration of experimental therapies [5]. To our understanding, there have been no published systematic reviews or meta-analyses examining the overall impact of Aβ-PET on changes in diagnosis and management. Our primary objective was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of Aβ-PET on the diagnosis, management, and level of confidence in the etiologic diagnosis of the cognitive impairment in the memory clinic setting.

METHODS

Literature search and selection

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [13]. A search of literature published between 1 January 2004 and 13 February 2018 was performed using the PubMed and MEDLINE databases. The search terms were ‘Pittsburgh Compound B’ AND ‘memory clinic’, ‘PiB’ AND ‘memory clinic’, ‘florbetapir’ AND ‘memory clinic’, ‘florbetaben’ AND ‘memory clinic’, and ‘flutemetamol’ AND ‘memory clinic’. The search was limited to human studies in English. We then reviewed the references from the retrieved articles for further relevant studies. We also searched through the program book of the latest Human Amyloid Imaging (HAI) 2018 (http://www.worldeventsforum.com/hai/2018-handbook/) to identify further potential studies. To be included, studies had to meet the following criteria: 1) an original research paper with a prospective or retrospective design or case series; 2) involved patients seen in a specialty memory clinic setting; 3) provided sufficient information to allow the calculation of crude percentage change in either diagnosis, management, or diagnostic confidence as study measures for the impact of Aβ-PET; and 4) published in English. Prospective studies were defined as those in which a group of patients with cognitive impairment attending memory clinics were followed up over time, with Aβ-PET performed during the follow-up period. Retrospective studies were defined as those that identified a group of cognitively impaired patients attending memory clinics with Aβ-PET already performed and used existing records to review the impact of Aβ-PET. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) articles in languages other than English; 2) review or systematic review articles; and 3) unpublished doctoral theses. Two investigators searched through the articles and reviewed all retrieved studies independently. If the two investigators disagreed about the eligibility of an article, it was resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each study: 1) the name of the first author; 2) the publication year; 3) study design (prospective, retrospective, or case series); 4) ligands used (i.e., 11C-PiB or 18F-tracers); 5) the age range or mean age of subjects; 6) the setting of the study, including whether the Aβ-PET was used according to AUC [5] or any other pre-defined restrictive criteria; 7) the characteristics of the subjects; 8) crude percentage change in diagnoses; 9) crude percentage change in management; 10) crude percentage change in diagnostic confidence; 11) other relevant data if applicable. If data from the same population had been published more than once, the most recent and complete studies were chosen. The main quality criterion in evaluating these studies was the involvement of dementia specialists (neurologists, geriatricians, or psychiatrists) seeing the patients in the memory clinic and reporting of the amyloid positivity of the Aβ-PET by professionals (i.e., radiologists or clinicians) who had completed appropriate training and qualified for reporting on Aβ-PET [5].

Statistical analysis for the meta-analysis

We computed the percentage of change in diagnoses and management for each study. Pooled estimates of the percentage change in diagnoses and management were calculated using random-effects meta-analyses, as the included studies involved different memory clinics and different populations. Sub-analyses were performed on the percentage change in diagnoses when Aβ-PET was used according to AUC or not; changes in diagnosis, specifically from AD to non-AD and from non-AD to AD, were also calculated. Analyses of the heterogeneity of the percentage change in diagnosis and management were performed with I2 statistic [14].

Publication bias was evaluated by inspection of the funnel plot that related the standard errors of studies to their event rates. If inspection of the funnel plot suggested the possibility of publication bias, the pooled percentage change in diagnosis or management corrected for publication bias were calculated (trim-and-fill method) [15]. Egger’s test was also performed [16].

Meta-regression was used to estimate the extent to which measured covariates (study design, i.e., prospective or retrospective design; ligands, i.e., PiB versus 18F-ligands, usage of Aβ-PET under AUC or not), mean age of subjects and prevalence of amyloid positivity in the studies could explain the observed variance between the studies. For all tests, p < 0.05 was deemed significant. All analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 (https://www.meta-analysis.com/index.php) (Biostat; Englewood, NJ, USA). Descriptive statistics were used for outcomes that were not suitable for meta-analyses.

RESULTS

Literature review: Identification and description of studies

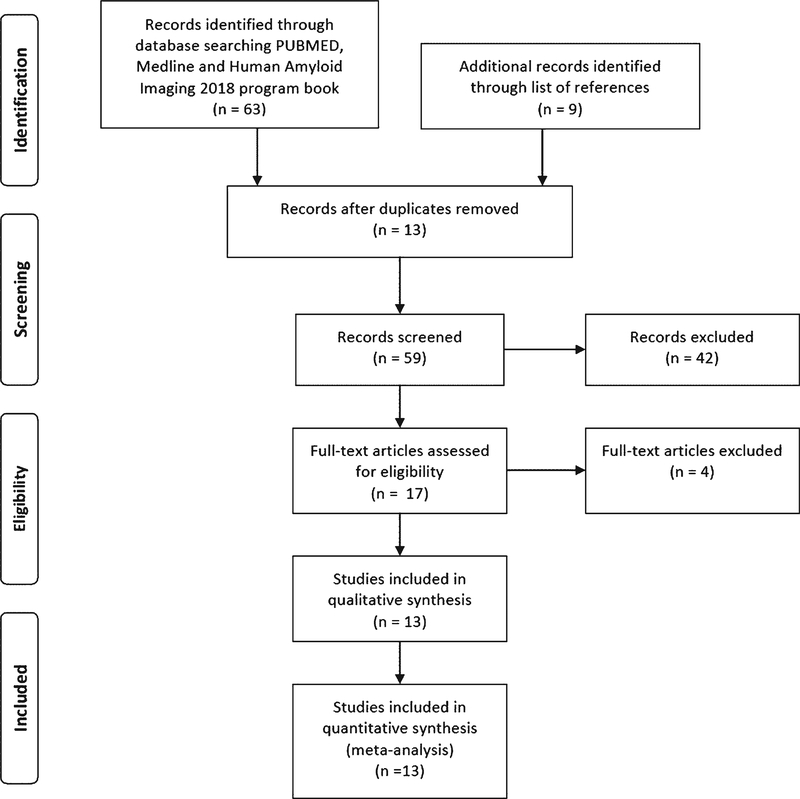

The literature search yielded a total of 63 citations (Fig. 1): 49 from PubMed, 13 from MEDLINE, and 1 from HAI. An additional 9 citations were identified from the reference lists. We removed 13 duplicates. After an initial screen of the titles and abstracts, another 42 were removed. Seventeen studies met the criteria for full-text review [3, 17–32]. However, two were excluded as only abstracts were available (one full-text article was in German) [31, 32], one was excluded because data from the same population has been published [28] and one study did not study the impact of Aβ-PET on diagnosis or management [29] (Supplementary Table 1). Ultimately, 13 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis and meta-analysis (Table 1) [3, 17–27, 30]. Thirteen studies [3, 17–27, 30] had reported on the change in diagnoses; five reported data with Aβ-PET performed under AUC, and ten reported data with Aβ-PET not performing according to AUC (Table 1). Thirteen studies had extractable data on the change in diagnoses from AD to non-AD [3, 17–21, 23, 24, 27, 30], and ten studies had extractable data on the change in diagnosis from non-AD to AD (Supplementary Table 2) [17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 27, 30]. Eight studies reported the data on the change in management (Table 1) [3, 17–19, 21–24]. Two corresponding authors of the articles were contacted for data concerning the change of diagnosis from AD to non-AD and from non-AD to AD [22, 25]. No previous systematic review or meta-analysis was identified.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the systematic review of literature.

Table 1.

A summary of the previous studies on the study of impact of amyloid imaging in memory clinic patients

| Studies | Year of publication | Study designs | Ligands used (criteria for a positive scan) | Mean age in years (range if available) | Setting (selected patients’ group or not) | Subjects and prevalence of amyloid positivity (for pre- Aβ-PET AD or non-AD group if available) | Change in diagnosis | Change in management plan | Change in confidence | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carswell et al. [19] | 2018 | Retrospective case series | 18F-florbetapir (visual read) | Median 66.7 (44.5–88) | AUC-like: 98; non-AUC: 2 | 100 (2 SCD; 31 MCI, 67 dementia) | 30 (31.3%)a (4 patients without post- Aβ-PET diagnosis yet) | 42 (42%)b | NA | Reduction in total number of investigations when Aβ-PET was available |

| Ceccaldi et al. [3] | 2017 | Prospective | 18F-Florbetaben (visual read) | 70.9±9.7 | 18 memory clinics; all fulfil AUC | A+ prevalence: 49% 205 (all dementia) | 137 (66.8%)a | 164 (80%)b | +30.2% | NA |

| A+ prevalence: 64.4% | A+: 57.6% (76/132) A-:83.6% (61/73) (p < 0.001) | A+:80.3% (106/132) A-: 79.5% (58/73) | ||||||||

| Weidman et al. [18] | 2017 | Retrospective | 18F-florbetapir (visual read and SUVR≥1.18) | 61.5 | 2 memory clinics; | 16 (10 dementia; 6 MCI) | 11 (68.8%)a | 13 (81.3%)b | NA (Confidence is measured as categories; 25% patients’ diagnoses had improved diagnostic confidence) | NA |

| AUC-like: 14; Non- AUC: 2 | A+ prevalence: 68.8% (AD: 88.9%; non-AD: only 1 patient who was A+) | |||||||||

| Zwan et al. [17] | 2017 | Prospective | 18F-flutemetamol (visual read) | 62±6 | ≤70 years old and diagnostic) dilemma after standardized evaluation (AUC-like); Two memory clinic | 211 (all dementia) | 41 (19%)a | 79 (37%)c | +19% (increased from 69±12% to 88±15%, p<0.01) | NA |

| A+ prevalence: 63% (AD: 76.4%; non-AD: 34.3%) | ||||||||||

| Apostolova et al. [24] | 2016 | Retrospective | 18F-florbetapir (SUVR≥1.17) | 65.9 (YOD n=24,

54.5±5.7; LOD n=28, 75.1±5.6) |

AUC-like; memory clinic | 52 (n=24 YOD, n=28 LOD) | 16 (30.8%) (LOD 43% versus YOD 17%, p=0.041)a | 36 (68.3%) (LOD 48% versus YOD 79%, p=0.02)d | NA | NA |

| 48 dementia, 4 MCI A+ prevalence: 71.2% (AD: 79.5%; non-AD: 46.2%) | AUC like: 30.8% (12/39) Non-AUC: 23.1% (3/13) | AUC like: 64.1% Non-AUC: 76.9% | ||||||||

| Bensaidane et al. [23] | 2016 | Prospective | 18F-NAV4694 (both visual reads and SUVR≥1.5) | 59.3±5.8 (48–68) | Atypical dementia (fulfil AUC);≤65 years old, atypical/unclear case with no specific diagnosis despite history, PE, NPA, MRI,18FDG-PET | 28 (all dementia) | 18 (64.3%)a | 11 (39.3%)d | +44% | Improved caregivers’ outcomesf |

| A+ prevalence: 50% (AD: 66.7%; non-AD: 30.8%) | A+: 28.6% (4/14) | 11 (39.3%)e | ||||||||

| Boccadi et al. [22] | 2016 | Prospective | 18F-florbetapir (visual reads) | 70.5±7 | Pre-scan confidence of AD diagnosis: 15–85%; non-AUC; 18 tertiary memory clinics | Total 228 | A-:35.7% (5/14) 62 (27.2%)a | 67 (29.4%)d | Confidence in AD: +15.2% if A+; −29.9% if A- | NA |

| Include 118 (52.8%) dementia and 110 MCI (48.2%) A+ prevalence: 59.6% (AD: 64%, non-AD: 48%) | ||||||||||

| Grundman et al. [re-analyzation of the same set of data as in 2013 study] [21] | 2016 | Prospective | 18F- florbetapir (visual reads) | 74.1±8.1 (54–96) | Pre-scan confidence of AD diagnosis: 15–85%;119 patients only had part of evaluation before Aβ-PET; memory clinic | Total 229 | 125 (54.6%, 95% CI 48.1–60.9%)a | 199 (86.9%, 95% CI 81.9–90.7%)c | +21.6% (95% NACI 81.9–90.7%) (n=84; those with etiologic diagnosis both in pre-scan & post-scan) | NA |

| Include 83 dementia (36.2%) and 146 MCI (63.8%) | A+: 52.2% (59/113) | AUC like 110 dementia out of 125 (88%)c | ||||||||

| A+ prevalence: 60.7% (AD:61.6%; non-AD: 57.1%) | A-: 56.9% (66/116) | Non-AUC 89 out of 104 (86%)c | ||||||||

| AUC like: 78 out of 125 (62.4%) Non-AUC: 47 out of 104 (45.2%) | ||||||||||

| Shea et al. [20] | 2016 | Retrospective case series | PiB (also 18FDG-PET) (SUVR≥1.42) | 77.2±7.9 | No restriction; memory clinic; non-AUC | 109 (7 MCI; 102 dementia); only 45 patients with PiB (43 dementia patients with PiB) | For 43 patients with PiB: change in diagnosis in 19 (44.2%)a | 26 (25.4%; out of 102 patients)d | NA | NA |

| A+: 48.8% (AD: 53%; non-AD: 36.4%) | (Overall 18FDG-PET and PiB) (36%; 37 out of 102 patients)a | |||||||||

| Mitsis et al. [26] | 2014 | Retrospective case series | 18F- florbetapir (visual reads) | 70±10.2 | Memory center; non-AUC | 30 (26 dementia,1 MCI, 3 SCI and 1 anxiety disorder) | 10 (33.3%)a | NA | NA | NA |

| A+ prevalence: 50% (AD: 66.7%; non-AD: 25%) | ||||||||||

| Sanchez-Juan et al. [25] | 2014 | Retrospective | PiB (also 18FDG-PET) (visual reads) | 65.0±8.2 | No restriction; memory clinic; non-AUC | Total 140, 130 dementia, 10 MCI | 13 (9%)a | NA | NA | NA |

| A+ prevalence: 50% (AD: 76.7%; non-AD: 18.2%) | ||||||||||

| Ossenkoppele et al. [27] | 2013 | Prospective | PiB (also 18FDG-PET but studied separately) (visual reads) | 64 | No restriction, i.e., non-AUC; memory clinic) | 154 (30 MCI, 15 SMC, 6 psychiatric diagnosis, 4 other neurological disease | 29 (18.8%)a [35 (23%) for both PiB and 18FDG-PET)] | NA | +16% (both PiB and 18FDG-PET) | For those with two-year follow-up, only 1 out of 23 patients change diagnosis |

| A+ prevalence: 48.1% (AD: 61%; non-AD: 37.8%) | ||||||||||

| Frederiksen et al. [30] | 2012 | Prospective | PiB (visual reads) | 65.7±9 | No restriction i.e., non-AUC; memory clinic; after history, PE, NPA, MRI,18FDG-PET, DAT, lumbar puncture | 57 (44 dementia, 3 SCC, 1 MCI, 2 with other neurological disease, 7 psychiatric diagnoses) | 13 (22.8%)a | NA | NA (Confidence is measured as categories; 49.1% patients’ diagnoses had improved diagnostic confidence) | Number needed to test to change diagnosis 4.4 |

| A+ prevalence: 47.4% (AD: 87.5%; non-AD: 31.7%) |

A, amyloid; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AUC, appropriate use criteria [5]; DAT, dopamine transporter scan; 18FDG-PET, 18-Flurodeoxyglucose; HAI, human amyloid imaging; LOD, late onset dementia; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not applicable; NPA, neuropsychological assessment; PE, physical examination; PiB, Pittsburgh Compound B; SCC, subjective cognitive complaint; SCD, suspected cognitive decline; SMC, subjective memory complaint; SUVR, standardized value uptake ratios; YOD, young onset dementia.

Defined as change in etiology (i.e., between AD or non-AD etiology) for MCI or dementia patients.

Initiation or withdrawal of any medication, additional diagnostic tests, referral to other specialists, or providing additional explanation or advice for patients or their families.

Included planned investigations, changes in medications (AD medications or psychiatric medications), or participation in a clinical trial.

Only involved change in AD medications.

Drug trial, lumbar puncture, referral to special therapist/psychologist.

Anxiety, depression, disease perception, future anticipation, quality of life.

Meta-analysis on the percentage change in diagnosis

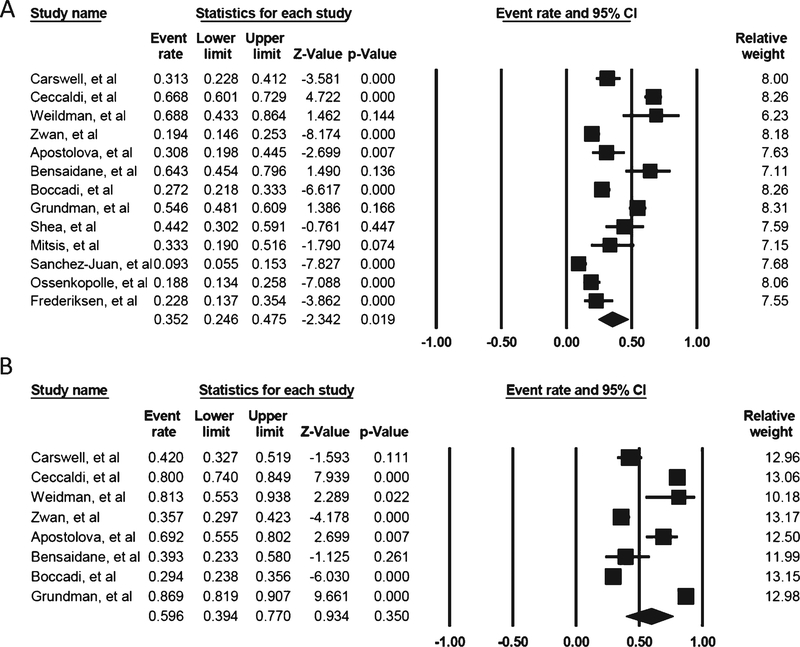

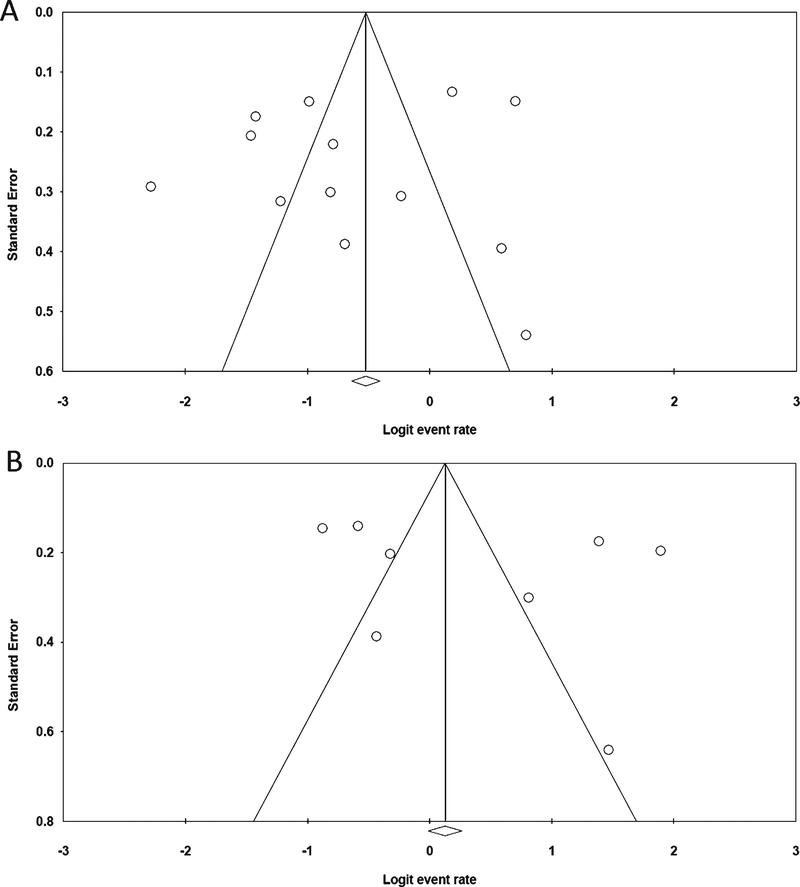

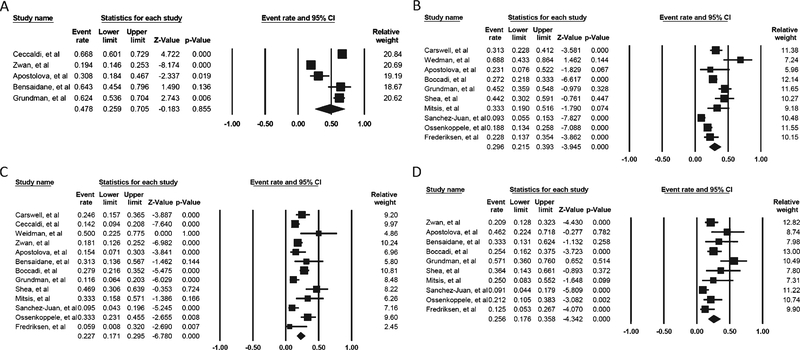

A total of 1,489 patients were reported in the 13 studies. The percentage change in diagnoses after the availability of Aβ-PET in the memory clinic ranged from 9–68.8%. The overall pooled percentage change in diagnoses was 35.2% (95% CI: 24.6–47.5; Supplementary Table 3), and there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 94.34%, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2A). The funnel plot was asymmetrical (Fig. 3A), showing a possible publication bias, but the Egger’s test indicated there was no publication bias (t = 0.67, p = 0.51). The trim-and-fill method did not alter the estimated percentage change (35.2%, 95% CI: 24.6–47.5).Sub-analyses showed that the pooled percentage change in diagnoses if Aβ-PET was used according to AUC (five studies involving 608 subjects) and not according to AUC (10 studies involving 881 subjects) were 47.8% (95% CI 25.9–70.5) (Fig. 4A) and 29.6% (95% CI: 21.5–39.3), respectively (Fig. 4B; Supplementary Table 3). While the pooled percentage of diagnosis change from AD to non-AD (13 studies involving 872 subjects) and change from non-AD to AD diagnosis (10 studies involving 349 subjects) were 22.7% (95% CI: 17.1–29.5) (Fig. 4C) and 25.6% (95% CI: 17.6–35.8) (Fig. 4D), respectively (Supplementary Table 3). Meta-regression for the overall change in diagnoses, using covariates including study design (i.e., prospective or retrospective design); ligands used (i.e., 11C-PiB versus 18F-ligands); whether Aβ-PET was performed according to AUC; mean age of subjects; and prevalence of amyloid positivity did not find that any of these factors could account for the variance between the various studies (Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 2.

(A) The forest plot for the overall percentage change in diagnosis. (B) The forest plot for the overall change in management.

Fig. 3.

(A) The funnel plot for the overall percentage change in diagnosis. (B) The funnel plot for the overall change in management.

Fig. 4.

(A) The forest plot for change in diagnosis if Aβ-PET is ordered according to AUC. (B) The forest plot for change in diagnosis if Aβ-PET is not ordered according to AUC. (C) The forest plot for change in diagnosis from AD to non-AD. D) The forest plot for change in diagnosis from non-AD to AD.

Meta-analysis on the percentage change in management

A total of 611 patients were reported among the eight studies. The percentage change in management after the availability of Aβ-PET in the memory clinic ranged from 25.4–81.3%. The overall pooled percentage in management was 59.6% (95% CI 39.4–77.0%), and there was substantial heterogeneity (I2: 96.866, p < 0.0001). The funnel plot was asymmetrical (Fig. 3B), and the trim-and-fill method showed an estimated pooled percentage change in management of 49.86% (95% CI 30.6–69.2%), showing a possible publication bias. However, the Egger’s test indicated there was no publication bias (t = 0.81, p = 0.44). Meta-regression for the overall change in diagnoses, using covariates including study design (i.e., prospective or retrospective design), ligands (i.e., 11C-PiB versus 18F-ligands) used, whether Aβ-PET usage was under AUC, mean age of subjects, and prevalence of amyloid positivity, did not reveal that any of these factors could account for the variance between the various studies (Supplementary Table 5).

Change in confidence in the diagnoses

For studies that have reported a numerical measure in the change in diagnostic confidence, there was an overall increase in confidence in diagnosis that ranged from 16 to 44% (Table 1) [3, 17, 23, 27, 28]. For studies that reported on the change in confidence as categories, there were improvements in the category of confidence in 25–49.1% of patients (Table 1) [18, 30]. One study reported that the confidence in diagnosis of AD increased by 15.2% if the Aβ-PET was amyloid positive and decreased by 29.9% if amyloid negative (Table 1) [3].

Other measures on impact of Aβ-PET on management of dementia

Carswell et al. reported that the numbers of diagnostic investigations per patient decreased from around 3 pre-Aβ-PET to 2 after Aβ-PET was available (p < 0.017) (Table 1) [19]. Grundman et al. reported,inagroupof119subjects,thattheavailability of Aβ-PET resulted in a net decrease in intended structural imaging, neuropsychological testing, lumbar puncture, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan by 24.4%, 32.8%, 94.7%, and 91.3%, respectively [28]. Bensaidane et al. reported that among the relatives of 28 patients, Aβ-PET findings improved caregivers’ outcomes in terms of anxiety, depression, disease perception, future anticipation, and quality of life [23].

DISCUSSION

The overall impacts of Aβ-PET from the reported literature are a change of diagnosis and management in 35.2% and 59.6%, respectively. Our meta-analysis suggests that performance of Aβ-PET under AUC yields a higher change in percentage in diagnosis than when Aβ-PET is not ordered according to AUC (47.8% versus 29.6%), although meta-regression did not show AUC accounting for variance of findings across the studies (Supplementary Table 4). Results were further collected on a change in diagnosis from AD to non-AD and from non-AD to AD (i.e., 22.7% and 25.6%, respectively) as these were the situations expected to have the greatest change in AD-specific medications usage. However, there were many other potential benefits that could not be analyzed and considered from our analyses, including reduction in unnecessary investigations, unnecessary treatments, relief of distress of caregivers, and potential involvement in clinical trials.

The largest ongoing study on the impact of Aβ-PET, the Imaging Dementia – Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study, had the goal of recruiting over 18,000 participants to study the impact of Aβ-PET on patients meeting AUC criteria and its impact on hospital admissions and emergency visits [33]. Interim results released in July 2017 involved 3,979 participants, with median age 75 (range 65–95); 64.4% carried a diagnosis of MCI and 35.6% suffered from dementia [33]. Changes in medical management were seen in 65.9–67.8% of the participants (including 48% with a change in AD drugs, 32.2–36% with a change in other drugs, and 15.3–23.9% who had changes in counseling). These percentages are higher than the 59.6% from our meta-analysis [33]. Although direct comparison in changes in diagnoses could not be made, the interim results of IDEAS noted an increase in the percentage of AD diagnoses from 78% to 95% in the amyloid positive group and a decline from 73% to 15% of AD in the amyloid negative group [33]. Aβ-PET may have an even bigger impact when the full results from IDEAS are released [33].

There were several limitations associated with this meta-analysis. First, the patients involved in these studies were heterogeneous in a number of dimensions: patient diagnoses ranged from subjective cognitive impairment to dementia. For the ordering of Aβ-PET, some followed the AUC and others did not, and for the change in diagnosis, some included a category of “indeterminate,” resulting in our inability to pool some of the data. Changes in management included changes in medications (AD-specific and psychiatric medications), changes in investigations, different family and patient advice based on the findings, and in some cases entry into clinical trials. However, in a “real-world” situation, heterogeneous groups of patients will be encountered as well. Six out of 13 studies were retrospective in nature [18–20, 24, 25]. There was a possibility of publication bias according to our analyses, in that positive rather than negative findings tend to be reported in the literature. The vast majority of studies included in the meta-analysis were from academic centers and represent a very biased sample of both patients and clinicians and our results are not generalizable to the whole population and might differ from IDEAS. Fortunately, the results of IDEAS will aid in addressing many if not most of these limitations. In the future, it will be increasingly important to address the impact of amyloid imaging on the temporal sequence of structural imaging, functional imaging, and metabolic imaging to optimize the impact on diagnosis and management in the memory clinic.

In conclusion, Aβ-PET has demonstrable and significant impacts on the changes in diagnoses and management among patients attending specialty memory clinic. The final results of IDEAS are eagerly awaited, and the expectation is that such beneficial changes, increased diagnostic accuracy, and aid on assuring patients and families will extend to general practice as well.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Aging Grant number 5 P50 AG0477266021 Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Todd Golde, PI).

Dr. Shea’s overseas training was sponsored by the 2017/2018 Hospital Authority Corporate Scholarship Program.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/18-0239r1).

SUPPLEMENTARYMATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180239.

REFERENCES

- [1].Alzheimer’s Association (2016) 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 12, 459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE, Kukull W (2012) Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 71, 266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ceccaldi M, Jonveaux T, Verger A, Krolak-Salmon P, Houzard C, Godefroy O, Shields T, Perrotin A, Gismondi R, Bullich S, Jovalekic A, Raffa N, Pasquier F, Semah F, Dubois B, Habert MO, Wallon D, Chastan M, Payoux P, NEUUS in AD study group, Stephens A, Guedj E (2017) Added value of 18F-florbetaben amyloid PET in the diagnostic workup of most complex patients with dementia in France: A naturalistic study. Alzheimers Dement 14, 293–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, Donohoe KJ, Foster NL, Herscovitch P, Karlawish JH, Rowe CC, Carrillo MC, Hartley DM, Hedrick S, Pappas V, Thies WH, Alzheimer’s Association, Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Amyloid Imaging Taskforce (2013) Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: A report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimers Dement 9, e-1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, Bedell BJ, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, Fleisher AS, Reiman EM, Sabbagh MN, Sadowsky CH, Schneider JA, Arora A, Carpenter AP, Flitter ML, Joshi AD, Krautkramer MJ, Lu M, Mintun MA, Skovronsky DM, AV-45-A16 Study Group (2012) Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloid-β plaques: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 11, 669–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rinne JO, Wong DF, Wolk DA, Leinonen V, Arnold SE, Buckley C, Smith A, McLain R, Sherwin PF, Farrar G, Kailajarvi M, Grachev ID (2012) [(18)F]Flutemetamol PET imaging and cortical biopsy histopathology for fibrillar amyloid β detection in living subjects with normal pressure hydrocephalus: Pooled analysis of four studies. Acta Neuropathol 124, 833–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE, Abrahamson EE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Tsopelas ND, Lopresti BJ, Ziolko S, Bi W, Paljug WR, Debnath ML, Hope CE, Isanski BA, Hamilton RL, DeKosky ST (2008) Post-mortem correlates of in vivo PiBPET amyloid imaging in a typical case of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 131, 1630–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Landau SM, Breault C, Joshi AD, Pontecorvo M, Mathis CA, Jagust WJ, Mintun MA, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2013) Amyloid-β imaging with Pittsburgh compound B and florbetapir: Comparing radiotracers and quantification methods. J Nucl Med 54, 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vandenberghe R, Van Laere K, Ivanoiu A, Salmon E, Bastin C, Triau E, Hasselbalch S, Law I, Andersen A, Korner A, Minthon L, Garraux G, Nelissen N, Bormans G, Buckley C, Owenius R, Thurfjell L, Farrar G, Brooks DJ (2010) 18F-flutemetamol amyloid imaging in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment: A phase 2 trial. Ann Neurol 68, 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Villemagne VL, Mulligan RS, Pejoska S, Ong K, Jones G, O’Keefe G, Chan JG, Young K, Tochon-Danguy H, Masters CL, Rowe CC (2012) Comparison of 11C-PiB and 18F-florbetaben for Aβ imaging in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 39, 983–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wolk DA, Zhang Z, Boudhar S, Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Arnold SE (2012) Amyloid imaging in Alzheimer’s disease: Comparison of florbetapir and Pittsburgh compound-B positron emission tomography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83, 923–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62, e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hardy RJ, Thompson SG (1998) Detecting and describing heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med 17, 841–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Weinhandl ED, Duval S (2012) Generalization of trim and fill for application in meta-regression. Res Synth Methods 3, 51–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zwan MD, Bouwman FH, Konijnenberg E, van der Flier WM, Lammertsma AA, Verhey FR, Aalten P, van Berckel BN, Scheltens P (2017) Diagnostic impact of [18F]flutemetamol PET in early-onsetdementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 9, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Weidman DA, Zamrini E, Sabbagh MN, Jacobson S, Burke A, Belden C, Powell J, Bhalla N, Roontiva A, Kuang X, Luo J, Chen K, Riggs G, Burke W (2017) Added value and limitations of amyloid-PET imaging: Review and analysis of selected cases of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Neurocase 23, 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Carswell CJ, Win Z, Muckle K, Kennedy A, Waldman A, Dawe G, Barwick TD, Khan S, Malhotra PA, Perry RJ (2018) Clinical utility of amyloid PET imaging with (18)F-florbetapir: A retrospective study of 100 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 89, 294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shea YF, Ha J, Lee SC, Chu LW (2016) Impact of (18)FDG PET and (11)C-PIB PET brain imaging on the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in a regional memory clinic in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 22, 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Grundman M, Johnson KA, Lu M, Siderowf A, Dell’Agnello G, Arora AK, Skovronsky DM, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, 18F-AV-45-A17 Study Group (2016) Effect of amyloid imaging on the diagnosis and management of patients with cognitive decline: Impact of Appropriate Use Criteria. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 41, 80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Boccardi M, Altomare D, Ferrari C, Festari C, Guerra UP, Paghera B, Pizzocaro C, Lussignoli G, Geroldi C, Zanetti O, Cotelli MS, Turla M, Borroni B, Rozzini L, Mirabile D, Defanti C, Gennuso M, Prelle A, Gentile S, Morandi A, Vollaro S, Volta GD, Bianchetti A, Conti MZ, Cappuccio M, Carbone P, Bellandi D, Abruzzi L, Bettoni L, Villani D, Raimondi MC, Lanari A, Ciccone A, Facchi E, Di Fazio I, Rozzini R, Boffelli S, Manzoni L, Salvi GP, Cavaliere S, Belotti G, Avanzi S, Pasqualetti P, Muscio C, Padovani A, Frisoni GB, Incremental Diagnostic Value of Amyloid PET With [18F]-Florbetapir (INDIA-FBP) Working Group (2016) Assessment of the incremental diagnostic value of florbetapir F 18 imaging in patients with cognitive impairment: The incremental diagnostic value of amyloid PET with [18F]-Florbetapir (INDIA-FBP) Study. JAMA Neurol 73, 1417–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bensaidane MR, Beauregard JM, Poulin S, Buteau FA, Guimond J, Bergeron D, Verret L, Fortin MP, Houde M, Bouchard RW, Soucy JP, Laforce R (2016) Clinical utility of amyloid PET imaging in the differential diagnosis of atypical dementias and its impact on caregivers. J Alzheimers Dis 52, 1251–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Apostolova LG, Haider JM, Goukasian N, Rabinovici GD, Chételat G, Ringman JM, Kremen S, Grill JD, Restrepo L, Mendez MF, Silverman DH (2016) Critical review of the Appropriate Use Criteria for amyloid imaging: Effect on diagnosis and patient care. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 5, 15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sánchez-Juan P, Ghosh PM, Hagen J, Gesierich B, Henry M, Grinberg LT, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, Huang EJ, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Gorno-Tempini M, Seeley WW, Boxer AL, Rosen HJ, Kramer JH, Miller BL, Jagust WJ, Rabinovici GD (2014) Practical utility of amyloid and FDG-PET in an academic dementia center. Neurology 82, 230–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mitsis EM, Bender HA, Kostakoglu L, Machac J, Martin J, Woehr JL, Sewell MC, Aloysi A, Goldstein MA, Li C, Sano M, Gandy S (2014) A consecutive case series experience with [18 F] florbetapir PET imaging in an urban dementia center: Impact on quality of life, decision making, and disposition. Mol Neurodegener 9, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ossenkoppele R, Prins ND, Pijnenburg YA, Lemstra AW, van der Flier WM, Adriaanse SF, Windhorst AD, Handels RL, Wolfs CA, Aalten P, Verhey FR, Verbeek MM, van Buchem MA, Hoekstra OS, Lammertsma AA, Scheltens P, van Berckel BN (2013) Impact of molecular imaging on the diagnostic process in a memory clinic. Alzheimers Dement 9, 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Grundman M, Pontecorvo MJ, Salloway SP, Doraiswamy PM, Fleisher AS, Sadowsky CH, Nair AK, Siderowf A, Lu M, Arora AK, Agbulos A, Flitter ML, Krautkramer MJ, Sarsour K, Skovronsky DM, Mintun MA, 45-A17 Study Group (2013) Potential impact of amyloid imaging on diagnosis and intended management in patients with progressive cognitive decline. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 27, 4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schipke CG, Peters O, Heuser I, Grimmer T, Sabbagh MN, Sabri O, Hock C, Kunz M, Kuhlmann J, Reininger C, Blankenburg M (2012) Impact of beta-amyloid-specific florbetaben PET imaging on confidence in early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 33, 416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Frederiksen KS, Hasselbalch SG, Hejl AM, Law I, Hojgaard L, Waldemar G (2012) Added diagnostic value of (11)C-PiB-PET in memory clinic patients with uncertain diagnosis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2, 610–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].de Wilde A OR, Pelkmans W, Bouwman F, Groot C, Zwan M, Yaqub M, Barkhof F, Lammertsma A, van der Flier W, van Berckel B, Scheltens P (2018) Impact of the appropriate use criteria: Effect of amyloid imaging on diagnosis and patient management in an unselected memory clinic cohort: The ABIDE Project. Human Amyloid Imaging 2018. program book, 357. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schonecker S, Prix C, Raiser T, Ackl N, Wlasich E, Stenglein-Krapf G, Mille E, Brendel M, Sabri O, Patt M, Barthel H, Bartenstein P, Levin J, Rominger A, Danek A (2017) [Amyloid positron-emission-tomography with [18 F]-florbetaben in the diagnostic workup of dementia patients]. Nervenarzt 88, 156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Imaging Dementia-Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study, https://www.ideas-study.org/2018/01/09/ideas-study-reaches-recruitment-goal-demonstrates-value-of-pet-scans/, Last updated Jan 9, 2018, Accessed on March 11, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.