Abstract

Background

Anopheles funestus is among the major malaria vectors in Kenya and sub-Saharan Africa and has been recently implicated in persistent malaria transmission. However, its ecology and genetic diversity remain poorly understood in Kenya.

Methods

Using 16 microsatellite loci, we examined the genetic structure of An. funestus sampled from 11 locations (n = 426 individuals) across a wide geographical range in Kenya spanning coastal, western and Rift Valley areas.

Results

Kenyan An. funestus resolved as three genetically distinct clusters. The largest cluster (FUN1) broadly included samples from western and Rift Valley areas of Kenya with two clusters identified from coastal Kenya (FUN2 and FUN3), not previously reported. Geographical distance had no effect on population differentiation of An. funestus. We found a significant variation in the mean Plasmodium infectivity between the clusters (χ2 = 12.1, df = 2, P = 0.002) and proportional to the malaria prevalence in the different risk zones of Kenya. Notably, there was variation in estimated effective population sizes between the clusters, suggesting possible differential impact of anti-vector interventions in represented areas.

Conclusions

Heterogeneity among Kenyan populations of An. funestus will impact malaria vector control with practical implications for the development of gene-drive technologies. The difference in Plasmodium infectivity and effective population size between the clusters could suggest potential variation in phenotypic characteristics relating to competence or insecticide resistance. This is worth examining in future studies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-018-3252-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Anopheles funestus, Malaria vector, Microsatellites, Kenya, Malaria risk zones, Population genetics

Background

The burden of malaria remains high in Africa despite the gradual decline that has been witnessed over the last decade. As of 2016, Africa accounted for > 90% of the 445,000 malaria deaths and 216 million cases were recorded worldwide [1]. The burden is, however, not uniform and characterized by spatio-temporal variability in different parts of Africa [2, 3]. In Kenya, the disease has been on the increase in some parts but with stable or declining parasite infection rates in other areas [2, 4]. Heterogeneity within vector populations could impact on spatio-temporal trends in malaria parasite transmission [5, 6]. This underscores the need to characterize the genetic structure of key vectors at a national scale for better assessment of the impacts on malaria control efforts [6, 7].

Anopheles funesus (s.s.) (hereinafter referred to as Anopheles funestus) is one of the four major malaria vector species widely distributed throughout tropical Africa and a key vector in Kenya [8, 9]. It is the nominal species and primary vector in the An. funestus group which comprises at least 13 sibling species [8]. The species is highly susceptible to malaria parasites and has a strong preference to feed on humans which endows it with a high vectorial capacity [10, 11]. Its potential capacity for rapid evolutionary adaptation is seen in the exhibition of divergent traits in response to scale up of long-lasting insecticidal net (LLIN) distribution. These include a shift toward diurnal [12] and outdoor feeding [13] habits, and development of multiple insecticide resistance mechanisms [14]. These biological and phenotypic traits relevant to disease epidemiology can be genetically determined with potential influence on the evolution of vector species or populations [15].

There have been a few studies on the population structure of An. funestus in Kenya. These date back to more than a decade ago preceding large scale LLIN measures which are known to have influenced vectorial systems and potentially associated selective adaptive responses in malaria vectors [16, 17]. Based on chromosomal inversions, Kamau et al. [18] observed levels of genetic differentiation among Kenyan An. funestus populations. A few studies in Kenya have employed microsatellite markers in determining the genetic structure of An. funestus, known to be highly informative for fine-scale population genetic analysis and lineage reconstruction [19, 20]. Braginets et al. [21] using microsatellites, found differentiation between An. funestus populations from coastal and western Kenya. This study was, however, limited in scope with just four sample sites (two from each region) and five loci. A pan-African microsatellite-based study found two population subdivisions in An. funestus [22]; however, this was not so useful for national scale inference. Delineating the fine-scale population structure of disease vectors such as An. funestus is crucial for understanding their epidemiological significance and their potential response to current and future vector control measures [6].

Effective malaria control towards elimination targeting vectors in Kenya will benefit from improved knowledge of the genetic heterogeneities of vector populations, especially An. funestus. Being among the key malaria vectors in Africa, this species has recently been implicated in persistent malaria transmission [23] with increases in the relative abundance following roll-out of LLINs in parts of Kenya [4]. Furthermore, the success of gene drives as developing strategies in the fight against malaria [24, 25] hinges on knowledge of the extent of genetic relatedness among local population of the target species. As part of the HEG Target Malaria Project, this study used 16 microsatellite loci to investigate the genetic structure of geographically distinct An. funestus samples from 11 locations spanning diverse malaria endemicities (coastal, western, Rift Valley) of Kenya. Our goal was to quantify the population structure of An. funestus with the objective of associating identified genotypes with geographical locations and explore possible links with malaria endemicity based on Plasmodium infection prevalence.

Methods

Sampling

We used DNA of An. funestus (s.s.) (hereinafter referred to as An. funestus) samples reported in a previous study [9]. The samples were from 11 sites spanning malaria risk areas in coastal, Rift Valley and western Kenya (Fig. 1, Table 1). The samples were identified using primers targeting the internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2) of ribosomal DNA [26] as previously described [9].

Fig. 1.

Map of Kenya showing the sampling locations

Table 1.

Anopheles funestus sampling sites in Kenya and number of specimens analyzed

| Region | County | Location (abbreviation) | Malaria endemicitya | Collection date (DD/MM/YY) | Collection method | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western | Kisumu | Ahero (H) | Lake Endemic | 4–16/11/2015 | CDC (Out) | 68 |

| Siaya | Usenge (US) | Lake Endemic | 23/7/2015 | IR | 31 | |

| Siaya | West Alego (AL) | Lake Endemic | 1/7/2017 | CDC (In/Out) | 61 | |

| Siaya | Mageta (MAG) | Lake Endemic | 8/6/2014 | IR | 8 | |

| Busia | Bunyala (BUN) | Lake Endemic | 3/7/2017 | CDC (In/Out) | 51 | |

| Busia | Samia (SAM) | Lake Endemic | 30/6/2017 | CDC (In/Out) | 102 | |

| Busia | Lwanya-Bumala (LN) | Lake Endemic | 3/7/2017 | CDC (In/Out) | 17 | |

| Rift Valley | Baringo | Kamnarok (B) | Highland Epidemic and semi-arid, seasonal | 12/8/2015 | IR | 11 |

| Coastal | Kilifi | Jaribuni (J) | Coast Endemic | 8/6/2017 | CDC (In/Out) | 31 |

| Kwale | Fihoni (FH) | Coast Endemic | 7/6/2017 | CDC (In/Out) | 22 | |

| Taita-Taveta | Njoro (T) | Coast Endemic | 6/7/2017 | IR | 24 |

Collection methods included indoor resting (IR) and CDC light traps (CDC) conducted indoors (In) and/or outdoors (Out)

a[2]

Detection of Plasmodium malaria parasites

We further screened the specimens for Plasmodium infections using PCR and melting analysis of amplicons in a RotorGene Q thermocycler (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) targeting non-coding mitochondrial sequences (ncMS) [27] and/or amplification of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene [28] as previously described [9].

Microsatellite genotyping

Anopheles funestus samples were genotyped at 16 polymorphic microsatellite markers spanning the genome [29, 30]. The markers were optimized into four multiplexes based on suitable primer annealing temperatures and non-overlapping expected allele size ranges (Additional file 1: Table S1) using the program Multiplex Manager v.1.0 [31]. Microsatellite detection from gDNA samples from each site (8–102 per site, n = 426) were run using the Type-it Microsatellite PCR kit (Qiagen): 6.25 μl of the 2X Type-IT master Mix, 2.5 μl of primer mix (2 μM each), 1 μl of RNase-free H2O and 4 μl of gDNA as template (10 ng/μl ≤ x ≤ 20 ng/μl). Thermal cycling conditions in a SimpliAmp Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Loughborough, UK) were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing (at 52–57 °C, depending on the multiplex) for 90 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; with a final extension at 60 °C for 30 min. Next, 1.25 μl of the PCR product was reconstituted in 3.75 μl of water and outsourced for fragment analysis at the DNA Sequencing Facility, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois, USA. The PCR fragments were separated on an ABI 3730XL (Applied Biosystems) sequence analyzer using the GeneScan™ 500LIZ™ size standard. The allele sizes were scored using GeneMarker software v.2.6.7 (SoftGenetics, LLC, Pennsylvania, USA) with each allele size score double-checked manually. Genotyping errors possibly due to null alleles, large allele dropouts and scoring of stutter peaks were initially checked using MICRO-CHECKER v.2.2.3 [32].

We estimated genetic diversity in the different geographical populations by calculating number of alleles per locus per population (A), allelic richness (RS), estimated population differentiation (FST) and inbreeding coefficients (FIS) per locus for each pair of population using FSTAT v.2.9.3 [33]. We assessed linkage disequilibrium (LD) between locus pairs within each population and deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium tested using Markov chain default parameters in GENEPOP [34]. An analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was performed on all geographical populations and a principle coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on FST run in GenAIEx v.6.5 [35]. We further plotted a neighbor-joining tree using pairwise population FST estimates to compare the structure of the different populations. Population structure was analyzed using Bayesian cluster analysis software STRUCTURE v.2.3.4 [36] using the admixture model with 50,000 for burn-in, 100,000 iterations and repeated 20 times for each value of K ranging from 1 to 12. The most likely number of populations, KMAX, was estimated using the Evanno method [37] implemented in CLUMPAK [38]. A correlation analysis comparing the genetic distance and geographical distance for all populations was conducted using a Mantel test with 100,000 randomizations in IBD v.1.52 [39]. To investigate whether any of the populations experienced recent genetic bottlenecks, a Wilcoxon sign-rank test for heterozygosity excess was applied under a two-phase model (TPM) with 20% non-single step mutation using the program Bottleneck v.1.2.02 [40].

Results

Genetic diversity in Anopheles funestus populations

All samples amplified reliably across the 16 loci showing the robustness of the multiplex design. The number of samples in each population ranged between 8–102 individuals with 8 of the 11 populations having ≥ 20 individuals (Table 1).

Genetic diversity estimates across all populations are shown in Additional file 1: Table S2. The levels of microsatellite polymorphism across loci and samples were moderate to high with the mean observed heterozygosity (HO) values within each of the geographical mosquito populations ranging from 0.48 in Njoro to 0.74 in Lwanya-Bumala. Following adjustment for variances in the number of individuals in each population, allelic richness (AR) ranged from 3.3 in Njoro to 5.1 in Ahero. We made a total of 1320 pairwise comparisons for LD of which 84 (7%) were significant (P < 0.005). Analysis of molecular variation (AMOVA) indicated significant molecular variation within and among the populations with 84% of the variation within individuals, 10% among individuals, and 6% among populations. The pairwise estimates of genetic differentiation among the 11 geographical populations ranged from -0.002 between Ahero and Lwanya -Bunyala to 0.32 between Njoro and Jaribuni (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pairwise comparison of genetic diversity (FST) among the 11 geographical A. funestus populations sampled

| Ahero | Kamnarok | Usenge | Mageta | Bunyala | West Alego | Njoro | Jaribuni | Lwanya-Bumala | Fihoni | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamnarok | 0.0184 | |||||||||

| Usenge | 0.0047 | 0.0252 | ||||||||

| Mageta | 0.0161 | 0.0336 | 0.0086 | |||||||

| Bunyala | -0.0017 | 0.0341 | 0.0043 | 0.0122 | ||||||

| West Alego | 0.0028 | 0.0329 | 0.0065 | 0.0209 | 0.0002 | |||||

| Njoro | 0.2553 | 0.2995 | 0.2798 | 0.2957 | 0.2734 | 0.2554 | ||||

| Jaribuni | 0.092 | 0.0924 | 0.0949 | 0.1125 | 0.0896 | 0.0866 | 0.3235 | |||

| Lwanya-Bumala | 0.0137 | 0.017 | 0.0196 | 0.0322 | 0.0149 | 0.0132 | 0.2814 | 0.0889 | ||

| Fihoni | 0.0482 | 0.0618 | 0.0526 | 0.0782 | 0.0465 | 0.0353 | 0.3132 | 0.0389 | 0.0491 | |

| Samia | 0.01 | 0.038 | 0.0117 | 0.0285 | 0.0089 | 0.0066 | 0.2665 | 0.1005 | 0.0256 | 0.0353 |

The bold values indicate comparisons that were significant following Bonferroni correction

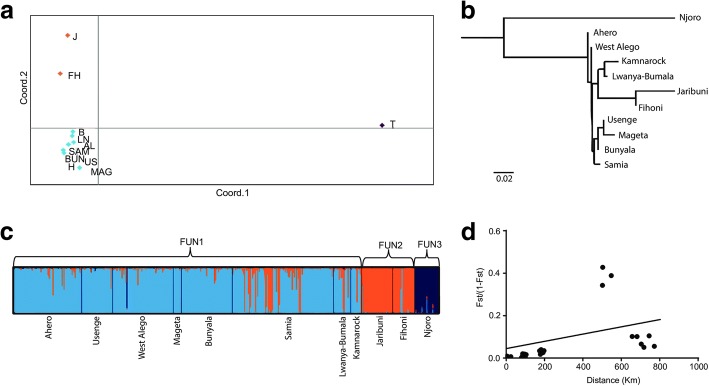

To visualize the genetic relatedness among individuals, we first performed PCoA. The top three PCoA components explained 54.21, 18.25 and 9.95% of the total variance and grouped the individuals into three main clusters (Fig. 2a). Similarly, a neighbor-joining (NJ) tree, based on pairwise FST estimates, showed three distinct populations for An. funestus (Fig. 2b). In support of population structuring, Bayesian clustering analysis with STRUCTURE showed that three population clusters (k = 3) best explain the genetic variance present in our data (Fig. 2c, Additional file 2: Figure S1). The first and largest subgroup (hereafter FUN1) comprised most An. funestus specimens collected in western Kenya (Ahero, Usenge, Lwanya-Bumala, Bunyala, W. Alego, Samia and Mageta Island) and Kamnarok, a riverine area of Baringo County in the Rift Valley. The second group (hereafter FUN2) included individuals from the coastal Kenyan sites of Fihoni and Jaribuni, while the smallest subgroup (hereafter FUN3) was associated with individuals exclusive to Njoro (Taita Taveta County) (Fig. 2c). The membership coefficients of geographical samples to their respective clusters/subgroup were relatively high, ranging between 79–98% for subgroup FUN1, 92–97% for subgroup FUN2 and 96% for subgroup FUN3 (Table 3). We further examined the extent of differentiation between the three subgroups within An. funestus by estimating the genotypic differentiation in GENEPOP using Markov chain default parameters. We found strong divergence among the clusters (P < 0.005) corroborating patterns of population structure observed within the species. Mantel tests on correlation between pairwise genetic and geographical distances indicated a weak and non-significant positive association between genetic and geographical distances (Mantel test: r = 0.33, P = 0.798) (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Population structure of Anopheles funestus in Kenya. a Principle coordinates analysis plot based on pairwise population FST estimates showing three clusters. b Neighbor-joining tree based on the FST pairwise estimates using 16 microsatellites. c Bayesian-based structure patterns K = 3 showing separation into 3 distinct clusters. d Isolation by distance comparing genetic distance versus geographical distance based on the Mantel test. The cluster FUN1 broadly include sites from western and Rift Valley, Kenya; coastal clusters FUN2 (Fihoni, Jribuni) and FUN3 (Njoro-Taita Taveta). Site abbreviations are indicated as in Table 1

Table 3.

Proportion of memberships in each of the three identified clusters

| Population | Group | Cluster | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | n | ||

| Ahero | FUN1 | 95 | 5 | 1 | 68 |

| Kamnarok | FUN1 | 81 | 18 | 0 | 11 |

| Usenge | FUN1 | 96 | 3 | 1 | 31 |

| Mageta | FUN1 | 98 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Bunyala | FUN1 | 96 | 3 | 0 | 51 |

| West Alego | FUN1 | 94 | 4 | 2 | 61 |

| Samia | FUN1 | 79 | 20 | 0 | 102 |

| Lwanya-Bumala | FUN1 | 79 | 20 | 1 | 17 |

| Jaribuni | FUN2 | 3 | 97 | 0 | 31 |

| Fihoni | FUN2 | 8 | 92 | 0 | 22 |

| Njoro | FUN3 | 3 | 1 | 96 | 24 |

Phenotypic patterns across identified clusters

Having observed three distinct clusters, we asked whether there is any phenotypic variation among these populations by examining the Plasmodium infectivity as a measure of malaria risk. We thus assessed the proportion of Plasmodium infectivity attributable to An. funestus of the total An. funestus group specimens analyzed per site representative of each cluster. Results revealed that mean Plasmodium sporozoite infectivity varied significantly between the clusters (χ2 = 12.1, df = 2, P = 0.002) being 8.4% (52/619; 95% CI: 6.4–10.9%), 3.1% (10/324; 95% CI: 1.6–5.8%) and 0% (0/29; 95% CI: 0–14.6%) for clusters FUN1, FUN2 and FUN3, respectively. We next estimated the effective populations (Ne) for each cluster using NeEstimator v.2 (Do et al. [41] based on linkage disequilibrium (LD). We found Ne to be 483.9 (95% CI: 419.8–566.9), 17.7 (95% CI: 15.0–20.9) and 71.2 (95% CI: 30.9–∞) for FUN1, FUN2 and FUN3, respectively.

Discussion

Gillies & De Meillon [42] had noted several polymorphic inversions in An. funestus and suggested possible genetic differentiation into locally adapted populations throughout its distribution range in tropical Africa. Collins & Besansky [10] further posited that greater discontinuities are not unexpected for this species given its breeding habitat in semi-permanent water bodies. The population genetic structure of this species has, however, been found to be shallow within local scales [22]. A similar shallow resolution has been observed for this species in West Africa using a combination of markers (chromosomal inversions, microsatellites and mitochondrial nad5 gene), with notable microsatellite differentiation of chromosomal forms facilitated by chromosome 3R inversions [43]. Here, we found An. funestus to be genetically subdivided across its range in Kenya. Most of the genetic variation was accounted for by within-population differences among individuals, consistent with previous findings [22, 43]. Nonetheless, we found population subdivision resulting in three genetically distinct clusters within An. funestus supported by Bayesian clustering (structure) analysis, NJ phylogeny and PCoA (Fig. 2a-c). The largest cluster (FUN1) broadly included samples from western Kenya (Ahero, Usenge, Bunyala, West Alego, Lwanya-Bumala, Samia, Mageta) and Kamnarok in the Rift Valley. Two clusters were recovered from coastal Kenya: FUN2 comprising samples from Jaribuni (Kilifi County) and Fihoni (Kwale County) and FUN3 unique to Njoro (Taita-Taveta County). Our findings indicate a much higher genetic diversity and subdivision for this species than previously reported in Kenya [18, 21]. Previous studies have highlighted significant genetic population differentiation between coastal and western Kenya populations, although with no evidence for genetic structure within coastal populations. Our recovery of additional structure in coastal Kenya could be attributed to the sampling scale with more sites and high number of loci employed.

Improving our understanding of the population structure and what drives genetic differentiation among mosquitoes will inform effective disease control. Heterogeneity within vector species resulting from evolution contributes to variability in malaria cases spatially and temporally [5, 6]. A few studies have examined patterns of genetic variation in relation to malaria epidemiological outcomes [44]. We found representation of samples within the clusters mirroring the degree of malaria endemicity or prevalence in Kenya. Western Kenya (represented by cluster FUN1) classified as Lake Endemic risk zone remains the hotbed of malaria in Kenya with a recent overall malaria prevalence of 27% [2]. About three-fold lower prevalence was estimated for the coastal region averaging 8%. Estimated mean Plasmodium infectivity attributed to An. funestus was 8.4% (52/619) for FUN1 (western Kenya) and 3.1% (10/324) for the coastal cluster FUN2, proportional to the mean malaria prevalence in the different risk zones of Kenya as highlighted earlier. Specimens from Kamnarok (riverine area in the Rift Valley) strongly assigned to the western cluster FUN1 (Fig. 2c). This site is a malaria hotspot within Baringo County with the overall highest prevalence rate of 23%, compared to less than 1% for the rest of the county [45]. Furthermore, estimated effective population sizes for An. funestus were 6 to 28-fold higher in cluster FUN1 (483) representing western Kenya, compared with the clusters from coastal Kenya [17 (FUN2) and 71 (FUN3)], a trend also exhibited in the genetic diversity measured by the number of alleles and observed heterozygosity (Additional file 1: Table S2). The size of a vector population correlates directly with its vectorial capacity [46]. Our findings on estimated population sizes are consistent with field data that indicate an increase in abundance of An. funestus, especially in western Kenya in recent times [4] following the dwindling importance Anopheles gambiae (s.s.) in malaria transmission. Given that efficient transmission translates to more infectivity in mosquitoes [47], our findings suggest variation in vectoral capacity among discrete populations of An. funestus which may impact differently on the epidemiology of malaria transmission across the different risk zones of Kenya. We recognize, however, that variation in mosquito infectivity rates could vary between sites [9, 48] likely influenced by other processes. For instance, different malaria transmission settings will impose a different malaria “reservoir” size in the human population, contributing to differences in mosquito infection rates. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that not all infections translate into infectivity, likely determined in part by vector factors (e.g. age structure, vector competence, biting preferences) [49] which may vary among the different clusters found in this study. Such difference in effective population size between the clusters could also relate to the extent anti-vector interventions in the represented areas as previously reported for other malaria vectors in West Africa [46]. Future research examining correlation in genetic structuring and malaria transmission should consider the contribution of other possible anopheline vectors within a given locality.

The Rift Valley has been identified as a barrier to gene flow in An. funestus [18] and An. gambiae [50], although the extent so far remains clear. While An. funestus has been documented in the Rift Valley [9], we found specimens from the riverine area (Kamnarok) of Rift Valley were strongly assigned to the western cluster, FUN1 (Fig. 2c). Further studies including samples from varied sites covering either side of the Rift Valley will shed light on the role of the Rift Valley in genetic structuring of this species. Our data found a weak positive correlation between geographical and genetic distance in An. funestus, indicative of strong genetic differences between clusters and possibly local adaptation. Samples from sites separated by between 5–97 km in western Kenya grouped together in cluster FUN1. We did not find any evidence of population bottlenecks among any of the population clusters.

The underlying cause for the population divergence observed between An. funestus in coastal and western Kenya remains unclear. We mainly encountered An. funestus indoors in western Kenya (FUN1) and outdoors at the coast (FUN2) (data not shown). Could the genetic and behavioral divergence be related to differences in the scale of vector control interventions between the regions or an effect of climate change? Such anti-vector interventions have been found also to impact population size of vector populations [46]. Mass distribution of long-lasting insecticidal bednets (LLINs) have taken place in Kenya since 2006 [51]. Insecticide resistance in vector populations has been widespread with large scale exposure resulting in altered abundance, behavioral shifts and general ecology of major vector populations (e.g. An. funestus, An. gambiae) [16]. Changes in the distribution among mosquitoes in the An. funestus group is evident where An. funestus remains the dominant sibling species in western Kenya and An. rivulorum in coastal Kenya, represented by cluster FUN2 [9]. As noted in parts of western Kenya, Anopheles funestus has reemerged as main malaria vector despite widespread use of insecticide-treated bednets, partly attributed to insecticide resistance [52]. Recently, genomic signatures of a major recent population decline of An. gambiae in coastal Kenya was reported, although not attributed to ITNs usage [53]. On the other hand, there are records of An. funestus having been eliminated from parts of Africa due to prolonged severe drought, e.g. [54], suggesting extreme climate variability can affect the survival of this species. Such a negative relationship between prolong drought and An. funestus occurrence raises the possibility of extreme climatic patterns in influencing the structuring among species. Western Kenya receives more rainfall than coastal Kenya and a combination of possible differences in the scale of interventions and climatic factors may be impacting on An. funestus population dynamics. Certainly, the factors driving the population structure of An. funestus in Kenya deserve further research.

Malaria vector control in Kenya will benefit from improved knowledge of the genetic heterogeneities within populations of An. funestus and their effects on malaria transmission. The persistent high transmission attributed to this species in western Kenya and mainly encountered indoors [9] will inform targeted measures such as indoor residual sprays (IRS). Pronounced genetic structure uncovered for this major malaria vector in Kenya has practical implications for the implementation of gene-drive technologies for mosquito control. However, extensive sampling of multiple populations will be needed to reveal the extent of the variation; this will help inform the design of such an approach, robust to natural genetic variation. Perhaps such a genetic approach will require multiple release points and may be more promising in western Kenya given the relative genetic uniformity. Since holistic malaria control using gene drive approaches needs to target multiple major malaria vectors [25], similar genetic studies should be extended to other vectors like Anopheles arabiensis which occurs in sympatry with An. funestus in most environments of Kenya and Africa as a whole.

Conclusions

We have unraveled subdivisions within An. funestus in Kenya revealing three genetically distinct clusters. We found variation in mean Plasmodium infectivity between the An. funestus clusters proportional to the mean malaria prevalence across risk areas of Kenya. This association does not, however, prove causality, as other processes could have contributed to the observed result. A holistic examination of all anophelines contributing to transmission in a given focus and their evolutionary pattern will shed light on the link between transmission and human malaria prevalence. Vector surveillance is integral to malaria elimination efforts, given vectors’ remarkable capacity for evolution and the need for fine-tuning control strategies in the event of changes in local transmission [55]. Most importantly, it is essential to start collecting population genomic data prospectively as an integral part of vector control interventions, to identify their responses to such measures, or the underlying cause of genetic structure and high population size of this species in western compared to coastal Kenya as observed in our data. As pointed out by the Anopheles gambiae Genomes Consortium [53], each intervention needs to be treated as an experiment and its effect analyzed on both mosquito and parasite populations. Only then can we improve the efficacy and sustainability of future interventions, while at the same time learn about basic processes in ecology and evolution.

Additional files

Table S1. Multiplex design and primer details of the 16 microsatellite markers used to study the genetic population structure of An. funestus in Kenya. Table S2. Genetic diversity across all populations. (DOCX 37 kb)

Figure S1. Evanno delta K, STRUCTURE results for K = 3 based on microsatellite clustering analysis. (TIF 118 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Nixon Onyimbo for support with field mosquito collection, Jackson Kimani for design of the study map and community members for providing access to their homesteads. We give special thanks to Dr David Weetman, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK, for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by a grant from the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health through the Vector-Based Transmission of Control: Discovery Research (VCTR) program of the Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative. Additionally, we gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this research by the following organizations and agencies: UK Department for International Development (DFID), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the Kenyan Government. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the donors.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- cox1

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1

- IR

Indoor resting

- LLIN

long-lasting insecticidal net

- ncMS

Non-coding mitochondrial sequences

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- s.l.

sensu lato

- s.s.

sensu stricto

Authors’ contributions

DKM, DPT and JMM designed the research. EOO, JOO and DPT performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the draft manuscript. DPT contributed new reagents/analytic tools. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was acquired from the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Ethics Review Committee (Non-SSC Protocol #388 and Non-SSC Protocol #310). Sampling was done after receiving informed consent from village elders and household heads.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Edwin O. Ogola, Email: eogola@icipe.org

Joel O. Odero, Email: jodero@icipe.org

Joseph M. Mwangangi, Email: JMwangangi@kemri-wellcome.org

Daniel K. Masiga, Email: dmasiga@icipe.org

David P. Tchouassi, Email: dtchouassi@icipe.org

References

- 1.WHO . World malaria report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), and ICF International . Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey 2015. Nairobi, Kenya, and Rockville, MD, USA: NMCP, KNBS, and ICF International; 2016. p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nkumama IN, O’Meara WP, Osier FH. Changes in malaria epidemiology in Africa and new challenges for elimination. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.President’s Malaria Initiative Kenya . Malaria Operational Plan Fy 2017. Washington: US Department of State, US Agency for International Development, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riehle MM, Guelbeogo WM, Gneme A, Eiglmeier K, Holm I, Bischoff E, et al. A cryptic subgroup of Anopheles gambiae is highly susceptible to human malaria parasites. Science. 2011;331:596–598. doi: 10.1126/science.1196759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fouet C, Kamdem C, Gamez S, White BJ. Genomic insights into adaptive divergence and speciation among malaria vectors of the Anopheles nili group. Evol Appl. 2017;10:897–906. doi: 10.1111/eva.12492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coetzee M, Fontenille D. Advances in the study of Anopheles funestus, a major vector of malaria in Africa. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dia I, Guelbeogo MW, Ayala D. Advances and perspectives in the study of the malaria mosquito Anopheles funestus. In: Manguin S, editor. Anopheles Mosquitoes. New Insights into Malaria Vectors. London: Intech. 2013. p. 828. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogola EO, Fillinger U, Ondiba IM, Villinger J, Masiga DK, Torto B, et al. Insights into malaria transmission among Anopheles funestus mosquitoes, Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:577. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3171-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins F, Besansky N. Vector biology and the control of malaria in Africa. Science. 1994;264:1874–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.8009215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manga L, Toto JC, Goff GL, Brunhes J. The bionomics of Anopheles funestus and its role in malaria transmission in a forested area of southern Cameroon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:387–388. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(97)90249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sougoufara S, Diédhiou SM, Doucouré S, Diagne N, Sembène PM, et al. Biting by Anopheles funestus in broad daylight after use of long-lasting insecticidal nets: a new challenge to malaria elimination. Malar J. 2014;13:125. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moiroux N, Gomez MB, Pennetier C, Elanga E, Djènontin A, Chandre F, et al. Changes in Anopheles funestus biting behavior following universal coverage of long-lasting insecticidal nets in Benin. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1622–1629. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riveron JM, Chiumia M, Menze BD, Barnes KG, Irving H, Ibrahim SS, et al. Rise of multiple insecticide resistance in Anopheles funestus in Malawi: a major concern for malaria vector control. Malar J. 2015;14:344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Neafsey DE, Waterhouse RM, Abai MR, Aganezov SS, Alekseyev MA, Allen JE, et al. Highly evolvable malaria vectors: the genomes of 16 Anopheles mosquitoes. Science. 2015;347:1258522. doi: 10.1126/science.1258522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM, Orindi BO, Muturi EJ, Midega JT, Nzovu J, et al. Shifts in malaria vector species composition and transmission dynamics along the Kenyan coast over the past 20 years. Malar J. 2013;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conn JE, Norris DE, Donnelly MJ, Beebe NW, Burkot TR, Coulibaly MB, et al. Entomological monitoring and evaluation: diverse transmission settings of ICEMR projects will require local and regional malaria elimination strategies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:28–41. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamau L, Munyekenye GO, Koekemoer LL, Hunt RH, Coetzee M. A survey of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group of mosquitoes from 10 sites in Kenya with special emphasis on population genetic structure based on chromosomal inversion karyotypes. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:664–671. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg NA, Li LM, Ward R, Pritchard JK. Informativeness of genetic markers for inference of ancestry. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1402–1422. doi: 10.1086/380416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández ME, Goszczynski DE, Lirón JP, Villegas-Castagnasso EE, Carino MH, Ripoli MV, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of microsatellites and SNP panels for genetic identification, traceability and assessment of parentage in an inbred Angus herd. Genet Mol Biol. 2013;36:185–191. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572013000200008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braginets OP, Minakawa N, Mbogo CM, Yan G. Population genetic structure of the African malaria mosquito Anopheles funestus in Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:303–308. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.69.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michel A, Ingrasci M, Schemerhorn B, Kern M, Goff G, Coetzee M, et al. Rangewide population genetic structure of the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:4235–4248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaindoa EW, Matowo NS, Ngowo HS, Mkandawile G, Mmbando A, Finda M, et al. Interventions that effectively target Anopheles funestus mosquitoes could significantly improve control of persistent malaria transmission in south-eastern Tanzania. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Esvelt KM, Smidler AL, Catteruccia F, Church GM. Emerging technology: concerning RNA-guided gene drives for the alteration of wild populations. eLife. 2014;3:e03401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Ogaugwu CE, Agbo SO, Adekoya MA. CRISPR in sub-Saharan Africa: applications and education. Trends Biotechnol. 2018. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Koekemoer L, Kamau L, Hunt R, Coetzee M. A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:804–811. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaumeau V, Andolina C, Fustec B, Ndam NT, Brengues C, Herder S, et al. Comparison of the performances of five primer sets for the detection and quantification of Plasmodium in anopheline vectors by real-time PCR. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Echeverry DF, Deason NA, Makuru V, Davidson J, Xiao H, Niedbalski J, et al. Fast and robust single PCR for Plasmodium sporozoite detection in mosquitoes using the cytochrome oxidase I gene. Malar J. 2017;16:230. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1881-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohuet A, Simard F, Berthomieu A, Raymond M, Fontenille D, Weill M. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite DNA markers in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Mol Ecol Notes. 2002;2:498–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2002.00290.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharakhov I, Braginets O, Grushko O, Cohuet A, Guelbeogo W, Boccolini D, et al. A microsatellite map of the African human malaria vector Anopheles funestus. J Hered. 2004;95:29–34. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esh011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holleley CE, Geerts PG. Multiplex Manager 1.0: a cross-platform computer program that plans and optimizes multiplex PCR. Biotechniques. 2009;46:511–517. doi: 10.2144/000113156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson WF, Wills DP, Shipley P. MICRO-CHECKER: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004;4:535–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00684.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goudet J. FSTAT (version 1.2): a computer program to calculate F-statistics. J Hered. 1995;86:485–486. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rousset F. genepop’007: a complete re-implementation of the genepop software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Resour. 2008;8:103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peakall P, Smouse R. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research - an update. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2537–2539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kopelman NM, Mayzel J, Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA, Mayrose I. Clumpak: a program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol Ecol Resour. 2015;15:1179–1191. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohonak A. IBD (isolation by distance): a program for analyses of isolation by distance. J Hered. 2002;93:153–154. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piry S, Luikart G, Cornuet J. BOTTLENECK: a computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective population size using allele frequency data. J Hered. 1999;90:502–503. doi: 10.1093/jhered/90.4.502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth G, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR. NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne) from genetic data. Mol Ecol Resour. 2014;14:209–214. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillies MT, De Meillon B. The Anophelinae of Africa south of the Sahara (Ethiopian Zoogeographical Region) Johannesburg: South African Institute for Medical Research; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michel AP, Grushko O, Guelbeogo WM, Lobo NF, Sagnon NF, Costantini C, et al. Divergence with gene flow in Anopheles funestus from the Sudan Savanna of Burkina Faso, West Africa. Genetics. 2006;173:1389–1395. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.059667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barnes KG, Irving H, Chiumia M, Mzilahowa T, Coleman M, Hemingway J, et al. Restriction to gene flow is associated with changes in the molecular basis of pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:286–291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615458114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Omondi CJ, Onguru D, Kamau L, Nanyingi M, Ong’amo G, Estambale B. Perennial transmission of malaria in the low altitude areas of Baringo County, Kenya. Malar J. 2017;16:257. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1904-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Athrey G, Hodges TK, Reddy MR, Overgaard HJ, Matias A, Ridl FC, et al. The effective population size of malaria mosquitoes: large impact of vector control. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Churcher TS, Trape J-F, Cohuet A. Human-to-mosquito transmission efficiency increases as malaria is controlled. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6054. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fontenille D, Simard F. Unravelling complexities in human malaria transmission dynamics in Africa through a comprehensive knowledge of vector populations. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;27:357–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohuet A, Harris C, Robert V, Fontenille D. Evolutionary forces on Anopheles: what makes a malaria vector? Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lehmann T, Hawley W, Grebert H, Danga M, Atieli F, Collins F. The Rift Valley complex as a barrier to gene flow for Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. J Hered. 1999;90:613. doi: 10.1093/jhered/90.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noor AM, Amin AA, Akhwale WS, Snow RW. Increasing coverage and decreasing inequity in insecticide-treated bed net use among rural Kenyan children. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCann RS, Ochomo E, Bayoh MN, Vulule JM, Hamel MJ, Gimnig JE, et al. Reemergence of Anopheles funestus as a vector of Plasmodium falciparum in western Kenya after long-term implementation of insecticide-treated bed nets. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:597–604. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The Anopheles gambiae Genomes Consortium. Genetic diversity of the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Nature. 2017;552:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Mouchet J, Faye O, Julvez J, Manguin S. Drought and malaria retreat in the Sahel West Africa. Lancet. 1996;348:1735–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65860-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castro M. Malaria transmission and prospects for malaria eradication: the role of the environment. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7:a025601. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Multiplex design and primer details of the 16 microsatellite markers used to study the genetic population structure of An. funestus in Kenya. Table S2. Genetic diversity across all populations. (DOCX 37 kb)

Figure S1. Evanno delta K, STRUCTURE results for K = 3 based on microsatellite clustering analysis. (TIF 118 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.