Conventionally, adolescent age group (10–19 years) was considered a relatively healthy period of life. Consequently, health services did not pay much attention to them. The HIV epidemic brought adolescent sexual and reproductive health into focus as a significant proportion of new HIV infections were taking place among them at the peak of the HIV epidemic. Although both new infections and HIV prevalence have been declining, the situation is still serious. In 2016, 2.1 million adolescents were living with HIV and 260,000 became newly infected with the virus. The number of adolescents living with HIV has risen by 30% between 2005 and 2016. The number of adolescents dying due to AIDS-related illnesses tripled between 2000 and 2015, the only age group to have experienced a rise. In 2016, 55,000 adolescents between the ages of 10 and 19 had died through AIDS-related causes. AIDS is now the leading cause of death among young people in Africa and the second leading cause of death among young people worldwide.[1]

Teen pregnancies are at a greater risk of mortality and morbidity. Therefore, they have been receiving attention with Millennium Development Goal and Sustainable Development Goal including targets for reducing maternal mortality. Our record globally on improving the situation needs more attention. The global adolescent birth rate has declined from 65 births per 1000 women in 1990 to 45 births per 1000 women in 2015.[2] However, approximately 16 million girls aged 15–19 years and 2.5 million girls under 16 years of age give birth each year in developing regions.[3] Complications during pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death for 15 to 19-year-old girls globally.[4] Every year, some 3.9 million girls aged 15–19 years undergo unsafe abortions.[5]

Gradually, other adolescent health problems came to fore. As we learn more about the development during adolescence, Klennet and Horton said “This Commission follows two previous Lancet Series in 2007 and 2012. The first Series highlighted what was then an emerging area of health and medicine called “adolescent health.” It drew the broad contours of the discipline—sexual and reproductive health, mental health, substance use, and chronic disease. The second Series sought to put the adolescent person at the center of our thinking about human health. It called for stronger links between adolescent health and wider global health programs and policies, highlighting serious data gaps.”[6,7,8]

The “Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing” in its executive summary argues that “Unprecedented global forces are shaping the health and wellbeing of the largest generation of 10-24 year old in human history. Population mobility, global communications, economic development, and the sustainability of ecosystems are setting the future course for this generation and in turn, humankind. At the same time, we have come to new understandings of adolescence as a critical phase in life for achieving human potential.” It concluded that investing in adolescents will yield a triple benefit–today, into adulthood, and the next generation of children.[9] Over half of the noncommunicable disease (NCD)-related deaths are associated with behaviors that begin or are reinforced during adolescence, including tobacco and alcohol use, poor eating habits, and lack of exercise.[10]

Adolescents explicitly began to be included in the strategies for global health that were being developed. The foreword to the “Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescent's Health” by UN Secretary General said, “The updated global strategy included adolescents because they are central to everything we want to achieve, and to the overall success of the 2030 Agenda. By helping adolescents to realize their rights to health, wellbeing, education and full and equal participation in Society, we are equipping them to attain their full potential as adults”.[11]

The overarching objectives of the global strategy are as follows:

Survive: End preventable deaths

Thrive: Ensure health and well-being; and

Transform: Expand enabling environments.

The main action areas to achieve the above objectives are country leadership, financing for health, health system resilience, investing in individual potential, community engagement, multisectorial action, addressing the needs of humanitarian and fragile settings, research, innovation, and accountability.

Making a case for investing in the capabilities of adolescents, Sheehan et al. said, “For interventions targeting physical, mental, and sexual health (including a human papilloma virus program), an investment of US$ 4.6 per capita each year from 2015 to 2030 had an unweighted mean benefit to cost ratio (BCR) of more than 10.0, whereas, for interventions targeting road traffic injuries, a BCR of 5.9 (95% CI 5.8-6.0) was achieved on investment of $0.6 per capita each year…. Investments in health and education will not only transform the lives of adolescents in resource-poor settings, but will also generate high economic and social returns.”[12] Thus, there is a general agreement globally that more investment is needed for adolescents' programs.

POLICIES AND PROGRAMS IN INDIA

The response in India also ran nearly parallel to global response. Following the International Conference on Population and Development (1994), the Reproductive and Sexual Health (RCH) program was launched in 1997 to reduce maternal, infant, and child mortality rates by gradually expanding the range and coverage of family welfare services to include the treatment of reproductive tract infection/sexually transmitted infection as well as adolescent health. The second phase of the program (RCH-II) was launched under the National Rural Health Mission in 2005. It also introduced several improvements in implementation including focus on disadvantaged areas of districts, participatory planning, and facility up gradation. During this phase, a conditional cash transfer scheme (Janani Suraksha Yojana) for institutional delivery was launched to promote them, and delivery by skilled birth attendants received a boost. Other maternal and child health services continued to be strengthened. However, reviews showed that immunization coverage needed to be substantially increased as well as diarrhea management and acute respiratory infections needed more attention.[13] The progress toward reducing infant, child, and maternal mortality continued.

Recognizing that maternal and child health cannot be further improved unless adolescent health and family planning, particularly birth spacing, is improved, a comprehensive strategy called Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health + Adolescents was launched in 2013. It emphasized high-impact interventions across the life cycle as well as continuum of care.[14]

Among other things, the + here denotes the inclusion of adolescents as a distinct life stage. Although the overall goal remained to reduce maternal, infant, and child mortality and total fertility, adolescent health services received attention. The priorities under adolescent health included nutrition, sexual and reproductive health, mental health, addressing gender-based violence (GBV), NCDs, and substance use. For this purpose, major interventions included iron and folic acid supplementation, adolescent health clinics for sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information, counseling and services, menstrual hygiene including provision of sanitary napkins, and preventive health checkups through school health. Community-based services including peer educators and delay in the age of marriage were to be promoted. A specific target was set to reduce anemia among girls and boys (15–19 years) at an annual rate of 6% from the baseline of 56% and 30%, respectively.[15]

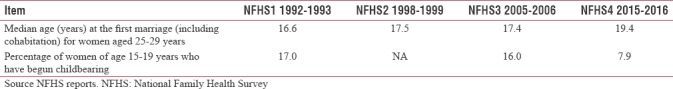

Sustained attention as well as secular trends in improving socioeconomic status led to reduction in adolescent fertility [Table 1]. During the period 1992–1993 (National Family Health Survey [NFHS] 1) and 2015–2016 (NFHS4), the percentage of women of age 15–19 who have begun childbearing declined from 17% to 7.9%. Median age at the first marriage for women aged 25–29 years during the same period increased from 16.6 to 19.4 years.

Table 1.

Changes in early marriage and pregnancy

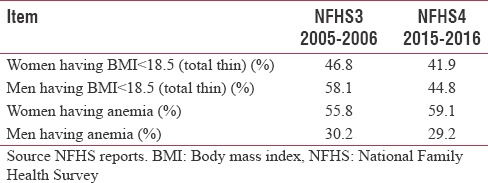

However, nutrition status remained nearly unchanged. The percentage of women aged 15–19 years with body mass index (BMI) <18.5 (total thin) marginally increased from 38.8% in 1998–1999 to 41.9 in 2015–2016. Anemia in the same age group increased from 56% to 59.1%. Percentage of boys aged 15–19 years with BMI <18.5 reduced from 58.1% in 2005–2006 to 44.8% in 2015–2016. However, proportion of boys with any anemia remained nearly stagnant [Table 2].

Table 2.

Changes in nutritional status (15-19 years)

Other health problems also persisted. For instance, in 2005–2006, it was estimated that 28.6% and 3.5% of boys and girls in the age group of 15–19 years used tobacco in any form.[16] The prevalence of morbidity due to mental health problems among adolescents was 7.3%, with a similar distribution between males and females (males 7.5% and females 7.1%).[17]

In view of the need for addressing these problems, the Government of India launched Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) in 2014. The RKSK strategy seeks the well-being of adolescents which constitute about one-fifth of India's population or about 230 million.[18] It proposes a holistic model which includes community-based health promotion and prevention along with strengthening of preventive, diagnostic, and curative services across the levels of health facilities. The six strategic areas of health identified are nutrition; SRH; NCDs; substance misuse; injuries and violence, including GBV; and mental health. These areas are to be addressed through seven critical components (7Cs), namely coverage, content, communities, clinics (health facilities), counseling, communication, and convergence. The guiding principles are adolescent participation and leadership, equity and inclusion, gender equity, and strategic partnerships. The interventions include convergence committees at various levels; peer educators; adolescent health day; adolescent-friendly health clinics (AFHCs); adolescent help line; training; and program planning, monitoring, and review.

SPECIAL JOURNAL ISSUE ON ADOLESCENT HEALTH

The purpose of this special issue on adolescent health is (a) to seek learning that can assist in the implementation of RKSK and (b) highlight persistent and emerging adolescent health issues. Below, we briefly discuss the papers in this issue under three broad headings: RKSK implementation, adolescent health issues addressed in RKSK, and emerging adolescent health issues.

Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram implementation

Three articles in this issue discuss the authors' experiences in assisting RKSK implementation. Their experience shows that much effort will be needed to effectively implement RKSK, but doing so can significantly increase the outreach and coverage of planned adolescent health services.

Wadhwa et al. describe their experiences on improving adolescent health services across high-priority districts in six states of India by providing technical support for the implementation of selected components of RKSK launched in 2014. Two approaches were implemented between October 2015 and December 2017, namely (a) strengthen the functioning of AFHCs in 95 high-caseload health facilities and (b) demonstrate other operational strategies outlined in RKSK program including strengthening of district committees on adolescent health, undertaking formative research for developing adolescent-focused communication strategy, and operationalizing weekly iron and folic acid supplementation program. After the baseline, training mentorship and quality improvement were undertaken to improve the functioning of AFHCs. Both availability and utilization of their services increased significantly. The formation and functioning of district committees on adolescent health were facilitated to improve the co-ordination of adolescent health interventions. A cross-sectional study among schoolgoing adolescent boys and girls was undertaken to assist in the formulation of communication strategy. An implementation model was used to develop framework for strengthening the weekly iron folic acid supplementation program. This experience shows that, when effectively operationalized, there is considerable potential of RKSK program to improve adolescent health services.

The next article in this category, by Pallavi Patel et al., describes the experiences of CHETNA, a nongovernmental organization in implementing capacity strengthening and organizing adolescent health days as well as the evaluative and process documentation support to this effort by the Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India. Although this project was begun before RKSK was launched, it was revised to focus on the following three health areas: SRH, nutrition, and substance abuse. The baseline and end line evaluation in the experimental block and control block in a district in Gujarat showed what can be accomplished by these interventions. While the knowledge of all functionaries and adolescents increased considerably, the changes in behaviors were more muted. The capacity-building efforts need to be supplemented by mentoring/handholding of the functionaries, which requires greater commitment to adolescent health.

Khushi Kansara et al. in their article describe their experiences in systematically using a behavior change approach – assess, build, create, develop, and evaluate – to pilot test a methodology of implementing adolescent health days. This methodology is currently being used by district health officials. Thus, innovative implementation of health innovations, particularly in new areas such as adolescent health, is possible using this approach.

Taken together, these three articles demonstrate approaches for implementation of the RKSK interventions – AFHCs, communication program, adolescent health committees at various levels to bring about convergence among different departments, weekly iron and folic acid supplementation, capacity building of all functionaries, community involvement, and organizing adolescent health days.

Mental health and noncommunicable diseases

Tapasvi Puwar et al. present the finding of a cross-sectional study among schoolgoing adolescents in a district in Gujarat using Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to assess mental health. The girls had higher mean SDQ score compared to boys in emotional problem score, hyperactivity score, total SDQ score, and prosocial score. Boys had higher mean score in conduct problem score and peer problem score, but the differences were not statistically significant. The most common risk factors for self-reported mental health issues were illiterate mother, occupation of parents, away from family during daytime, nuclear family, severe addiction to alcohol in the family, financial problems in the family, and daily physical punishment. Their findings indicate that mental health aspects in RKSK program require emphasis.

Jayashree et al. in their study in two pregraduation institutes in South India found that depression (49% among females and 36% among males) and anxiety (55%) disorders are high among adolescents and need more attention.

Most of the risk factors for NCDs are due to change in lifestyle among adolescent age group. Therefore, Tapasvi Puwar et al. investigated the prevalence of such risk factors among schoolgoing adolescents in a district of Gujarat. This cross-sectional study documents that not having fruits and not doing physical activity daily are the major factors for NCD. Promotion of healthier practices is needed as a part of RKSK program.

As electronic media are gaining prominence, a systematic review by Abhay Gaidhane et al. on the effect of electronic media on diet, exercise, and physical activity among adolescents finds that, to date, there are very few studies, all in developed countries, and that the quality of evidence was rated as “very low” due to too little information or too few data to be able to reach any conclusions. Another systematic review by Mahalaqua Nazi Thatib et al. of electronic media's effects among children and adolescents on substance abuse also reaches similar conclusions. To fully utilize their benefits and mitigate harmful effects, electronic media need to be effectively utilized. Therefore, more research is needed which can provide credible evidence on their design and implementation.

Emerging adolescent health issues

Cervical cancer

Swain and Parida report on their intervention to sensitize randomly selected nursing students at a university college on the prevention of cervical cancer through pre- and post-test design. They found that, although 65% were well oriented about cancer cervix and its prophylactic measures, only 15% were aware about HPV vaccine. The sensitization program succeeded in significantly increasing knowledge regarding cervical cancer and its prophylaxis measures. More than half of the participants received HPV vaccination after the recommendation from the experts. Although the number of participants is not large enough to generalize the results, the authors concluded that periodic sensitization through education intervention may act as a cascade for girls and help them to be aware about the preventive aspect of cervical cancer. They also recommend that large studies on HPV vaccination among young girls are needed.

Body image

Subhagini Ganeshan et al. carried out a study among college-going adolescent girls to find out the proportion of girls dissatisfied about their body image and the association of various factors with body image dissatisfaction and to ascertain weight control behavior. This study shows that body image dissatisfaction is no longer a Western concept and affects Indian adolescent girls to a great extent. Factors such as BMI, sociocultural pressures to be thin, and depression were all significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction.

Cigarette packaging

Archana Bhat et al. carried out a qualitative study of a female group of university students to explore adolescent's perception about the introduction of new cigarette packaging and plain packaging of cigarette packs. Although more studies are needed, they raise the issue that plain packaging will reduce the positive image related to smoking. As nearly 75% of all cigarettes sold every year in India are sold as loose cigarettes, studies are needed to know the effect of sale of single cigarettes on smoking. Nevertheless, positive impact of warning labels was seen among nonsmokers, whereas the current smokers' perception was unaffected.

Heavy school bags

Possible adverse impact of heavy school bags on health has caused concerns, and the Maharashtra State government has prescribed safe upper limits. However, this study by Shyam Vinayak Ashtekar et al. found that, in two rural schools in Maharashtra, half of the bags carried by students in 8th and 9th standards were heavy. An intervention on creating awareness among teachers followed by among students succeeded in reducing the mean weight of the bags. Nevertheless, despite interventions, 19% of students in 8th standard carried heavier bags than the prescribed limit. Hence, they recommend that reduction in the daily subject load is necessary.

REFERENCES

- 1.AVERT. Young People, HIV and AIDS. 2018. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 05]. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-social-issues/key-affected-populations/young-people .

- 2.The World Bank. Adolescent Fertility Rate. 2018. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 08]. Available from: https://www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/sp.ado.tfrt .

- 3.UNFPA. Girlhood, Not Motherhood: Preventing Adolescent Pregnancy. New York: UNFPA; 2015. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 08]. Available from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/dataset/fertility/adolescent-rate.shtml . [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Global Health Estimates 2015: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2015. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 05]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darroch J, Woog V, Bankole A, Ashford LS. Adding it Up: Costs and Benefits of Meeting the Contraceptive Needs of Adolescents. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinert S. Adolescent health: An opportunity not to be missed. Lancet. 2007;369:1057–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60374-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnick MD, Catalano RF, Sawyer SM, Viner R, Patton GC. Seizing the opportunities of adolescent health. Lancet. 2012;379:1564–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinert S, Horton R. Adolescent health and wellbeing: A key to a sustainable future. Lancet. 2016;387:2355–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387:2423–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 03]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations. The Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health (2016-2030) 2015. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 03]. Available from: http://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/globalstrategyreport2016-2030-lowres.pdf .

- 12.Sheehan P, Sweeny K, Rasmussen B, Wils A, Friedman HS, Mahon J, et al. Building the foundations for sustainable development: A case for global investment in the capabilities of adolescents. Lancet. 2017;390:1792–806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 03]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/reproductive-maternal-newborn-child-and-adolescent-health_pg .

- 14.Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 03]. Available from: http://www.nhm.gov.in/nrhm-components/rmnch-a.html .

- 15.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. Strategic Approach to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) in India. 2013. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 03]. Available from: http://www.nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/RMNCH+A/RMNCH+A_Strategy.pdf .

- 16.Global Youth Tobacco Survey. 2009. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 03]. Available from: http://www.who.int/fctc/reporting/annesonindia.pdf .

- 17.National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) NMHS of India: Prevalence, Patterns and Outcomes (2015-16) Supported by the Ministry of Health and family Welfare, Government of India and Implemented by NIMHJANS: In Collaboration with Partner Institutions. 2016. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 08]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/pmc/articles/pmc5419008 .

- 18.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. Rashtriya Kishor Swaasthya Karyakram (RKSK): Strategy Handbook. New Delhi. 2014. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 03]. Available from: www.nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/RKSK/RKSK_Strategy_Handbook.pdf .