Abstract

Background:

Body image relates to how people think and feel about their own body. In today's society, with the growing sense of ideal body image, adolescents try to lose or gain body weight to attain that perfect body. Body image perception is still naive, and this research will try to understand these unexplored areas, where there is paucity of body image-related studies.

Objectives:

The objective of the study is to find out the proportion of girls dissatisfied about body image, and the association of various factors with body image dissatisfaction and to ascertain the weight control behaviors adopted by adolescent college girls.

Methodology:

A cross-sectional study was done among 1200 college girls in Coimbatore. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data on various factors associated with body image dissatisfaction. Body mass index (BMI) of the participants was calculated.

Results:

Body image dissatisfaction was there among 77.6% of the girls. It was found that factors such as higher BMI, sociocultural pressure to be thin and depression were all significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction. The most commonly followed weight control behaviors were eating small meals and skipping meals. Improving the appearance and body shape were the main reasons for weight control behaviors.

Conclusion:

This study establishes the fact that body image dissatisfaction is no longer a western concept and affects Indian adolescent girls to a great extent. Hence, effective interventions have to be planned to increase awareness on ideal body weight and protect our young generation from pressures of negative body image.

Keywords: Adolescent, body image dissatisfaction, body weight, college girls, weight control

INTRODUCTION

Body image relates to how people think and feel about their own body. It relates to a person's perceptions, feelings, and thoughts about his or her body and is usually conceptualized as incorporating body size estimation, evaluation of body attractiveness, and emotions associated with body shape and size.[1]

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to body dissatisfaction due to the physiological, social, and psychological changes they are going through.[2] For adolescent girls, a range of body and social changes take place during and following puberty that can strongly influence their body image and become more pronounced by late adolescence.[3]

Perception of overweight and dissatisfaction with body size, rather than actual weight appears to be a potent force behind girls' dieting and weight control behaviors. Such behavior is related to negative physical and psychological changes and can lead to life-threatening conditions including eating disorders.[4] With rapid economic development and affluence, there is a progressive shift toward thinness as the ideal body shape and increasing concerns about body weight leading to dissatisfaction.[5]

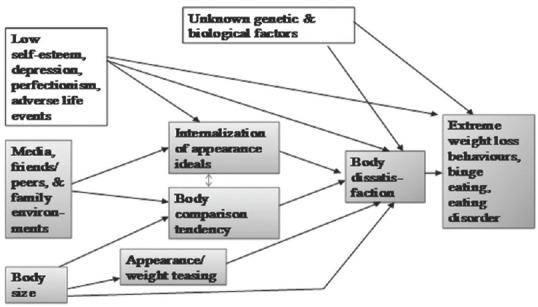

Factors contributing to body image problems have been studied, and biopsychosocial model of risk factors was developed by Paxton.[6] This model [Figure 1] suggests that biological factors, such as body size, together with individual psychological characteristics such as low self-esteem, depression, and perfectionism, which refers to individuals desire to attain idealistic goals without failing, social influences, and interpersonal interactions, all contributes to the development of body image.

Figure 1.

Biopsychosocial model of risk factors for the development of body dissatisfaction by Susan J Paxton

There is a paucity of studies in India and gaps remain in our understanding of the factors responsible for the development of attitudes and behavior related to body weight and appearance among adolescent girls.[7]

Hence, this study aimed to find out the proportion of girls dissatisfied about body image, and the association of various factors with body image dissatisfaction and to ascertain the various weight control behaviors adopted by adolescent college girls.

METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted in a college located in an urban area of Coimbatore. With an estimated prevalence of body image dissatisfaction of 33.3% from a study in Mangalore,[8] sample size was calculated to be 978, with the precision of 3.3%, and nonresponse 20%. After approval by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee, 1220 college going adolescent girls in the age group of 18–19 years, were enrolled in the study by convenience sampling. After obtaining informed consent, a semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect the data on body image dissatisfaction and the associated factors namely demographic factors, socioeconomic and media influence, sociocultural pressure, self-esteem, perfectionism, and depression. Furthermore, data regarding weight control measures adopted were collected.

Measuring body image dissatisfaction

Body image dissatisfaction of the adolescents was measured using the Stunkard silhouettes Figure Rating Scale (FRS). It includes drawing of nine silhouettes ranging from very thin (1) to very heavy (9). Students were presented with female versions of the FRS and were asked to identify the figure they currently perceived themselves with, and the figure they would wish to have. Discrepancy scores were calculated based on the difference between the actual and ideal figures chosen. Positive scores indicate a desire to be smaller, while negative scores suggest a desire to be larger. The discrepancies between the current and desired figures were interpreted as an indication of body image dissatisfaction.[9,10] Hence, participants who had discrepancies in the figures chosen were identified as having body image dissatisfaction.

Measuring factors associated with body image dissatisfaction

The factors associated with body image dissatisfaction such as self-esteem, depression, sociocultural pressure, media influence, and perfectionism were measured using previously validated questionnaires and using Likert scale ratings, and score was given.[11,12,13,14,15] Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was used to measure Self-esteem with the Likert scales ranging from strongly agree (score 1) to strongly disagree (score 4). Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem.[11] Depression was measured using Center of Epidemiological studies (CES) Depression questionnaire with Likert scale which graded from rarely to mostly with the scoring of 0–3, respectively. Score on the CES-Depression questionnaire range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more severe levels of depressive symptoms.[12]

Socio-cultural pressure was measured with the pressure grading from none (score 1) to a lot of pressure (score 5). The scoring ranges from 10 to 50.[13] Media influence was measured using SATAQ 3 questionnaire with Likert scale grading of completely disagree to completely agree with a scoring of 1–5. The scoring ranges from 14 to 70.[14] Perfectionism was measured using the EDI questionnaire with Likert scale grading from always to never with score from 1 to 6, respectively. The scoring ranges from 6 to 36.[15]

The height and weight of the participants were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. According to the WHO standards in our study, BMI <18.5 kg/m2 was classified as underweight, a BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 was considered normal, overweight is 25–29.9 kg/m2, and obesity is ≥30 kg/m2.[16]

The association between the possible risk factors and body image dissatisfaction was assessed by univariate analysis using Chi-square test, t-test, and odds ratio was estimated. Those factors found significant by univariate analysis were further subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify factors that were significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction.

RESULTS

Majority of the study participants (60.6%) were from an urban background. About 67.5% of them belonged to Class I and Class II and 32.5% of them belong to Class III and Class IV socioeconomic status according to modified Prasad classification.[17]

Based on the BMI, about half (53.6%) of them were having normal BMI while 26.7% of them were undernourished, 15.7% were overweight, and 3.9% were obese.

The study showed that 947 (77.6%) girls were dissatisfied with their body image (95% CI: 75.2–79.9). Among the 947 participants who were dissatisfied the mean score of the perceived silhouette figure was 4.0 ± 1.5 (four corresponds to the normal range of BMI), and the mean of the chosen ideal silhouette was 3.3 ± 0.8 (three corresponds to the lower end of the normal BMI toward the underweight range).

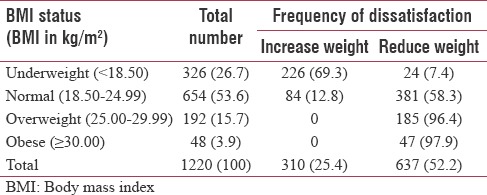

Table 1 shows the distribution of body image dissatisfaction based on the calculated BMI of the participants. It shows that 58.3% of the participants of normal BMI also were dissatisfied with their appearance and wanted to reduce weight. In the underweight category, 23.3% were satisfied, and 7.4% wanted to reduce their weight further showing the tendency of the college students to have a thin appearance. Tables 2 and 3 show the association of body image dissatisfaction with its risk factors by univariate analysis. Higher BMI, higher socioeconomic status, depression, increased sociocultural pressure to be thin, media influence and low self-esteem were found to be significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction.

Table 1.

Distribution of body image dissatisfaction of study participants based on calculated body mass index (n=1220)

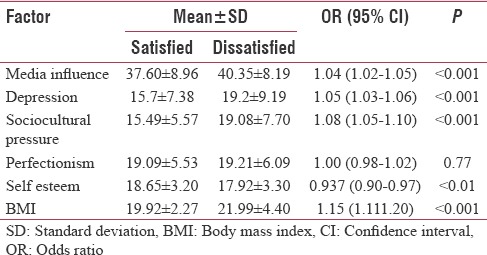

Table 2.

Association of body image dissatisfaction with the risk factors (continuous variables) by univariate analysis

Table 3.

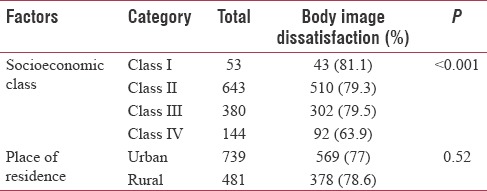

Association of body image dissatisfaction with the risk factors (categorical variables) by univariate analysis

There was no significant association with the place of residence and perfectionism.

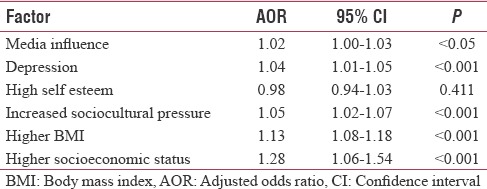

Table 4 shows multivariate logistic regression exploring the association of body image dissatisfaction with those risk factors having statistically significant association with body image dissatisfaction by univariate analysis.

Table 4.

Association of body image dissatisfaction with the risk factors by multivariate logistic regression

Factors such as higher BMI, higher socioeconomic status, depression, and increased sociocultural pressure to be thin were found to be significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Among the 1220 students who participated in the current study, 791 (64.8%) of them had undertaken at least one weight control measure in the past 1 year. Of which 157 (19.8%) were satisfied and 634 (80.2%) were dissatisfied with their body image.

Among the multiple options of weight control measures adopted, the most common method was taking small meals (53.2%) followed by skipping meals (42.7%). Extreme measures such as taking laxatives (5.3%) and vomiting after meals (9.7%) were also seen.

Among participants who followed weight control measures, multiple reasons were given by them, of which 61.7% gave improving the appearance and body shape as the main reason for going in for weight control measures and 33.5% said to look better in clothes.

Our study also showed that 67% of participants who were dissatisfied with their body image were adopting one or more weight control measures while in the satisfied group 57.5% have adopted weight control measures. The difference was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.01) with an odds ratio of 1.49 (1.13–1.97).

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that body image dissatisfaction was there in 77.6% of the adolescents. This was similar to a study done by Sasi and Maran in Chennai among adolescents above 12 years of age which showed a prevalence of 81%.[18]

Our study also showed that 23% of the underweight people were satisfied with their BMI, and among those who were dissatisfied 7.4% wanted to reduce their weight further. Similarly, 71% of the normal BMI category was dissatisfied with their appearance of which 58.3% wanted to reduce their weight. This clearly shows the tendency for liking toward thin body shapes.

Socioeconomic status of an individual impacts their body image perceptions and satisfaction/dissatisfaction with the body. Studies have shown that body image dissatisfaction is seen more among higher socioeconomic status.[19] Our study also showed that the proportion of girls having body image dissatisfaction, who belonged to class I socio economic status are slightly higher than other classes and it was statistically significant.

Studies have also shown that urban adolescents have more body image dissatisfaction compared to rural,[20] but our study did not show any significant association.

Our study also showed that increased socio-cultural pressure, depression and higher BMI had significant association with body image dissatisfaction. Literature also shows that these factors are associated with body image dissatisfaction.[21,22,23]

Our study failed to show any significant association between body image dissatisfaction and media influence, self-esteem, and perfectionism which were also established in other studies.[24,25,26]

This study also showed that 64.8% of the college students had undertaken at least one weight control measure in the past 1 year. It also showed that girls who were dissatisfied with their appearance tend to do more weight control measures and the most common weight control measures were eating small meals, skipping meals, and avoiding certain foods. It also showed that the majority of students have cited improving the appearance and to look better in clothes as main reasons for going in for weight control measures. This was also found similar to other studies which showed that appearance was a major motivation for dieting practices.[27,28]

Our study was done in a large sample and measured the different factors which were associated with body image dissatisfaction. The study of these factors is crucial for improving our understanding of body image dissatisfaction in adolescent girls which is still naive in our cultural setup.

Limitations

Although the study area was in a college which had both self-financing and government aided divisions which brought together adolescents from different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, it was done in only one college - this restriction may limit the generalizability of the findings.

CONCLUSION

This study establishes the harsh fact that body image perceptions and dissatisfaction is no longer a western concept and affects our adolescent girls to a great extent. There is also a tendency favoring toward thin body figures which is evident in the study.

Recommendations

Effective interventions to improve awareness on ideal body weight, media literacy, and harmful effects of extreme weight control measures have to be planned, and young people both maintain a healthy body weight and are protected from the pressure of negative body image and weight control practices.

Further studies are recommended to establish the cause-effect relationship of the identified factors.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Thomas V Chacko for his valuable inputs, the participants and the entire department for their support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grogan S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children. London: Routledge; 1999. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.art-therapy.gr/images/stories/book_library/new/%CE%92%CE%99%CE%92%CE%9B%CE%99%CE%91/art%20therapy/Body-Image-Understanding-Body-Dissatisfaction-in-Men-Women-a.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clay D, Vignoles VL, Dittmar H. Body image and self-esteem among adolescent girls: Testing the influence of sociocultural factors. J Res Adolesc. 2005;15:451–77. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littleton HL, Ollendick T. Negative body image and disordered eating behavior in children and adolescents: What places youth at risk and how can these problems be prevented? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6:51–66. doi: 10.1023/a:1022266017046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann AH, Wakeling A, Wood K, Monck E, Dobbs R, Szmukler G, et al. Screening for abnormal eating attitudes and psychiatric morbidity in an unselected population of 15-year-old schoolgirls. Psychol Med. 1983;13:573–80. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700047991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cash TF, Morrow JA, Hrabosky JI, Perry AA. How has body image changed? A cross-sectional investigation of college women and men from 1983 to 2001. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1081–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paxton SJ. Evidence, Understanding and Policy: A Perspective from Psychology – Prevention, Early Intervention and Treatment of Body Image Problems. Body Image: Evidence, Policy, Action. Report of a Multidisciplinary Academic Seminar on Behalf of the Government Equalities Office. United Kingdom. 2003. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/.../uploads/.../Susan_Paxton_-_Body_Image_Seminar__3_.docx .

- 7.Chugh R, Puri S. Affluent adolescent girls of Delhi: Eating and weight concerns. Br J Nutr. 2001;86:535–42. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Priya D, Prasanna KS, Sucharitha S, Vaz NC. Body image perception and attempts to change weight among female medical students at Mangalore. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:316–20. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo WS, Ho SY, Mak KK, Lam TH. The use of Stunkard's figure rating scale to identify underweight and overweight in Chinese adolescents. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhuiyan AR, Gustat J, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Differences in body shape representations among young adults from a biracial (Black-white), semirural community: The Bogalusa heart study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:792–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray-Little B, Williams VS, Hancock TD. An item response theory analysis of the rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997;23:443–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reina SA, Shomaker LB, Mooreville M, Courville AB, Brady SM, Olsen C, et al. Sociocultural pressures and adolescent eating in the absence of hunger. Body Image. 2013;10:182–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson JK, van den Berg P, Roehrig M, Guarda AS, Heinberg LJ. The sociocultural attitudes towards appearance scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35:293–304. doi: 10.1002/eat.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord. 1983;2:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eveleth PB. Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Am J Hum Biol. 1996;8:786–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangal A, Kumar V, Panesar S, Talwar R, Raut D, Singh S, et al. Updated BG Prasad socioeconomic classification, 2014: A commentary. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59:42–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.152859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasi RV, Maran K. Advertisement pressure and its impact on body dissatisfaction and body image perception of women in India. Glob Med J Indian Ed. 2012;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felden EP, Teixeira CS, Gattiboni BD, Bevilacqua LA, Confortin SC, da Silva TR. Body image perception and socioeconomic status in adolescents: Systematic review. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2011;29:423–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra SK, Mukhopadhyay S. Eating and weight concerns among sikkimese adolescent girls and their biocultural correlates: An exploratory study. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:853–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calzo JP, Sonneville KR, Haines J, Blood EA, Field AE, Austin SB, et al. The development of associations among body mass index, body dissatisfaction, and weight and shape concern in adolescent boys and girls. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:517–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stice E, Whitenton K. Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: A longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:669–78. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsella AJ, Shizuru L, Brennan J, Kameoka V. Depression and body image satisfaction. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1981;12:360–71. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:460–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fortes Lde S, Cipriani FM, Coelho FD, Paes ST, Ferreira ME. Does self-esteem affect body dissatisfaction levels in female adolescents? Rev Paul Pediatr. 2014;32:236–40. doi: 10.1590/0103-0582201432314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boone L, Soenens B, Braet C. Perfectionism, body dissatisfaction, and bulimic symptoms: The intervening role of perceived pressure to be thin and thin ideal internalization. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30:1043–68. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Klem ML, Burke LE, Soulakova JN, Marcus MD. Impact of addressing reasons for weight loss on behavioral weight-control outcome. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brink PJ, Ferguson K. The decision to lose weight. West J Nurs Res. 1998;20:84–102. doi: 10.1177/019394599802000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]