Our findings advocate for personalized treatment approaches for AUD and highlight the need for carefully considering the role of age in prevention and intervention efforts.

Abstract

Aims

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are linked with numerous severe detrimental outcomes. Evidence suggests that there is a typology of individuals with an AUD based on the symptoms they report. Scant research has identified how these groups may vary in prevalence by age, which could highlight aspects of problematic drinking behavior that are particularly salient at different ages. Our study aimed to (a) identify latent classes of drinkers with AUD that differ based on symptoms of AUD and (b) examine prevalences of latent classes by age.

Short summary

Our findings advocate for personalized treatment approaches for AUD and highlight the need for carefully considering the role of age in prevention and intervention efforts.

Methods

We used data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III). Current drinkers aged 18–64 who met criteria for a past-year AUD were included (n = 5402).

Results

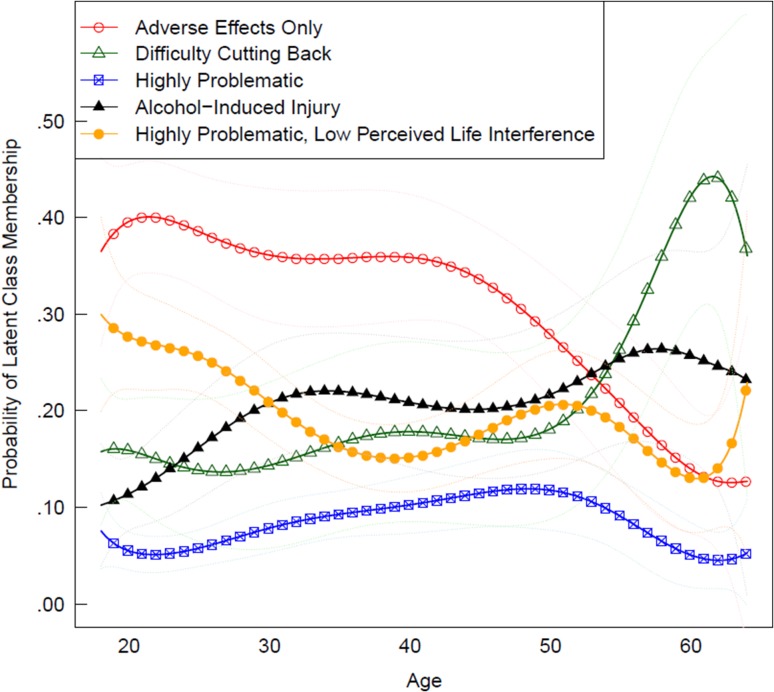

Latent class analysis (LCA) based on 11 AUD criteria revealed 5 classes: ‘Alcohol-Induced Injury’ (25%), ‘Highly Problematic, Low Perceived Life Interference’ (21%), ‘Adverse Effects Only’ (34%), ‘Difficulty Cutting Back’ (13%) and ‘Highly Problematic’ (7%). Using time-varying effect modeling (TVEM), each class was found to vary in prevalence across age. The Adverse Effects Only and Highly Problematic, Low Perceived Life Interference classes were particularly prevalent among younger adults, and the Difficulty Cutting Back and Alcohol-Induced Injury classes were more prevalent as age increased.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that experience of AUD is not only heterogeneous in nature but also that the prevalence of these subgroups vary across age.

INTRODUCTION

Heavy and frequent alcohol use continues to be a critical public health concern in the USA (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016), costing an estimated $249 billion in 2010 (Sacks et al., 2015). In 2014, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimated that 17 million individuals over the age of 12 met criteria for a past-year alcohol use disorder (AUD). AUD is characterized by behavioral and physical symptoms (e.g. withdrawal, craving) as well as an impaired ability to control one’s alcohol use despite experiencing a variety of negative consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria include a wide range of symptoms that can comprise AUD. Symptoms of alcohol abuse and dependence are currently combined into a single disorder criterion with subclassifications of mild (2–3 symptoms out of 11), moderate (4–5 symptoms) and severe (6 or more symptoms), though cut-offs for AUD have been shown to be problematic (Lane and Sher, 2015). Experience of AUD is linked to increased risk for a number of negative health outcomes (e.g. risk for cardiovascular diseases [Rehm et al., 2016; Roerecke and Rehm, 2014], stroke [Patra et al., 2010], cirrhosis of the liver [Rehm et al., 2010]) and behavioral outcomes (e.g. alcohol-induced injury, motor vehicle crashes, academic/occupational outcomes [White and Hingson, 2013]). Prevalence of AUD peaks in young adulthood, or approximately ages 18–25, with 1 in 8 (12.3%) young adults experiencing an AUD (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016). Among adults aged 26 or older, ~5.9% met criteria for a past-year AUD.

Heterogeneity of AUD

A growing body of research supports that AUD is heterogeneous across individuals in nature (see Litten et al., 2015). The typology of AUD has been examined in several different ways. Person-centered analytic techniques, such as latent class analysis (LCA), have been used to identify distinct subgroups of individuals who experience AUD based on shared characteristics. Several studies have used LCA to showcase that DSM-5 AUD lies on a continuum of symptom severity. For example, in a sample of college student heavy drinkers, Rinker and Neighbors (2015) found two distinct classes of student subgroups: a ‘Less Severe’ class (86%) that had a low probability of endorsing DSM-5 AUD indicators, and a ‘More Severe’ class (14%) that positively endorsed over half the criteria. These methods have been extended to populations outside of college students as well. Other samples include an Australian cohort study following adolescents into young adulthood (Swift et al., 2016) and a large, population-based sample (i.e. Wave 2 [years 2004–2005] from the large National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions [NESARC]; Shireman et al., 2015), finding 3- and 4-class solutions, respectively, to best fit the data. Despite the differences in the best-fitting number of classes across sample type, these findings highlight that AUD is a heterogeneous disorder that may be best classified using distinct subgroups that characterize the heterogeneity among adults with AUD.

Beyond identifying latent classes of AUD in terms of level of symptom severity, LCA has also shown utility in identifying classes based on both AUD criteria and other characteristics about an individual (e.g. Moss et al., 2007, 2010) or to use attributes about drinkers as predictors of AUD latent class membership (e.g. Smith and Shevlin, 2008; Rinker and Neighbors, 2015). One common individual characteristic that has yielded predictive utility of AUD latent classes is age. For example, using data from NESARC Wave I, Moss and colleagues (2007) derived five classes based on 26 attributes of drinkers, including family history of alcoholism, mental health symptomatology and other substance use disorders in addition to AUD symptomatology. They found that the class prevalences differed by age, with some more common among young adults and other more common among middle-aged adults. Moreover, Jester and colleagues (2016) followed a community sample of families from ages 15–45 and examined their developmental trajectory of alcoholism severity and identified their classes based on their trajectory. Classes included ‘Low Symptoms’, ‘Developmentally Limited’ (peaked in the early 20s and decreased rapidly), ‘Developmentally Cumulative’ (symptoms increased through the teenage years and levelled off in early 40s for men and 30 s for women), ‘Young Adult Onset’, and ‘Early Onset Severe’. The different trajectories highlight an important point that in addition to AUD symptomology being heterogeneous within a particular age, the prevalence of varying classes may also change.

AUD across age

While we know that AUD lies on a continuum in terms of severity and characteristics and that AUD symptomology develop differently across age, we know far less about how classes of individuals with AUD change as age increases. Some efforts have been made to better understand the role of age in one’s experience of an AUD. For example, Moss and colleagues (2010) compared classes on age, with membership in some categories being predominantly comprised of young adults and in other classes, middle-aged adults. While this information demonstrates that prevalence of certain classes may be more common at different age groups, the way in which class prevalences change across age is not well understood. In addition, much prior work on this topic has characterized classes in terms of their AUD diagnosis in addition to many other factors, such as whether they meet criteria for other disorders (e.g. other substance use disorder, demographic factors). While this approach broadly encompasses characteristics about individuals within each latent class, it obfuscates the specific alcohol-related harms individuals experience that put them at risk for having an AUD. In moving toward more innovative personalized intervention approaches, it may be beneficial for researchers and clinicians to have knowledge about the harms individuals experience that put them at risk, and how these problematic subtypes vary in prevalence across age.

Current study

The current study used innovative statistical methods to extend our knowledge on latent classes of individuals who meet criteria for an AUD by examining the way in which class probabilities change across continuous age. Aim 1 was to identify subgroups of individuals with an AUD based on their profile of symptomatology. LCA was used to identify subgroups of drinkers with AUD based on shared characteristics (i.e. commonly reported AUD symptoms). Aim 2 was to examine changes in probabilities of these latent classes across ages 18–64 by integrating LCA with a semiparametric regression approach to model class prevalence as a non-linear function of time, which is a simplified version of time-varying effect modeling (TVEM; Tan et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015). Higher order polynomial terms for age were incorporated as predictors of latent class membership to allow class probabilities to vary flexibly across age.

METHODS

Participants and procedure

Data were from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III; Grant et al., 2014), which consists of a nationally representative sample of 36,309 non-institutionalized US adults aged 18 and older. Data were collected in 2012–2013. Hispanic, Black and Asian adults were oversampled to provide more reliable estimates within the sample. Participants were compensated $90 for their time. Survey protocols were approved by the institutional review board of the National Institutes of Health and Westat.

Study analyses were restricted to those aged 18–64 years old, given low rates of AUD for those aged 65 years and older (Balsa et al., 2008). The sample was limited to those who reported any alcohol use in the past year and met criteria for a past-year AUD (at least 2 of the 11 criteria as described below; n = 5402). Incorporating survey weights, our analytic sample was 66.4% male. In terms of race/ethnicity, 66.4% were White, non-Hispanic; 11.9% were Black, non-Hispanic; 14.9% were Hispanic; 4.5% were Asian/Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic; and 2.4% were American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic.

Measures

Past-year AUD was measured using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—DSM-5 Version (AUDADIS-5; Grant et al., 2015). The AUDADIS-5 is a diagnostic interview for use in non-clinical settings. Participants reported whether they experienced a variety of symptoms within the past 12 months. Questions in NESARC-III were matched with DSM-5 criteria in order to determine whether they met each of the 11 DSM-5 criteria (see Supplemental Table 1). For example, responses to NESARC-III questions, ‘…have a period when you kept on drinking more than you meant to?’ and ‘…have a period when you kept on drinking for longer than you had intended to?’ were used to determine whether they met the DSM-5 criteria of, ‘…had times when you ended up drinking more, or longer than you intended?’ In this case, for example, if they positively endorsed either NESARC-III question, they were coded as having met this DSM-5 criterion. Weighted prevalences for each criterion are listed in Table 1. Participants were identified as having a past-year AUD if they experienced at least 2 of the 11 DSM-5 criteria.

Table 1.

Weighted prevalence of AUD criteria among those with a past-year AUD

| In the past year, have you: | Weighted prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Criteria 1. Had times when you ended up drinking more, or longer, than you intended? | 64.1 |

| Criteria 2. More than once wanted to cut down or stop drinking, or tried to, but couldn’t? | 48.6 |

| Criteria 3. Spent a lot of time drinking? Or being sick or getting over other after-effects? | 23.9 |

| Criteria 4. Wanted a drink so badly you couldn’t think of anything else? | 45.5 |

| Criteria 5. Found that drinking—or being sick from drinking—often interfered with taking care of your home or family? Or caused job troubles? Or school problems? | 9.1 |

| Criteria 6. Continued to drink even though it was causing trouble with your family or friends? | 29.2 |

| Criteria 7. Given up or cut back on activities that were important or interesting to you, or gave you pleasure, in order to drink? | 8.3 |

| Criteria 8. More than once gotten into situations while or after drinking that increased your chances of getting hurt (such as driving, swimming, using machinery, walking in a dangerous area, or having unsafe sex)? | 44.9 |

| Criteria 9. Continued to drink even though it was making you feel depressed or anxious or adding to another health problem? Or after having had a memory blackout? | 33.2 |

| Criteria 10. Had to drink much more than you once did to get the effect you want? Or found that your usual number of drinks had much less effect than before? | 41.2 |

| Criteria 11. Found that when the effects of alcohol were wearing off, you had withdrawal symptoms, such as trouble sleeping, shakiness, restlessness, nausea, sweating, a racing heart, or a seizure? Or sensed things that were not there? | 69.7 |

Analytic plan

Regarding the LCA (Aim 1), each of the 11 symptoms of AUD was used as binary indicators of latent classes. Models with one through eight classes were compared based on fit indices, including Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), percent agreement and entropy to determine the optimal model. The bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) was also used to compare models with k classes relative to a model with k + 1 classes. Models also were selected based on interpretability and distinction. SAS PROC LCA (Lanza et al., 2015) was used to conduct LCA and the BLRT was tested using the LCAbootstrap SAS Macro (Dziak and Lanza, 2016).

To examine latent class probabilities across age (Aim 2), we used an approach similar to TVEM (Tan et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015), but instead of using a non-parametric spline basis function, prevalence rates of the multinomial latent class outcome were allowed to vary flexibly across ages 18–64 by estimating them as a polynomial function of age (age, age2, … age6). Age was centered at 35 years to address multicollinearity of the polynomial terms. When model selection was conducted separately within three age groups, a five-class model was found to best fit individuals aged 18–29 as well as individuals aged 30–44. A four-class model was the best fit for those aged 45–64. Given the similarity in interpretation across each age bin, the latent class measurement model was specified to be invariant across ages to maintain consistent interpretations of the latent classes. Sample weights were incorporated in all analyses to provide generalizable estimates.

RESULTS

Descriptively, the proportion of adults with AUD was found to have a largely linear shape, with rates of AUD highest among young adult drinkers (peaking at ~39.7% around age 18) and lowest in older adult drinkers (~7.6% around age 64).

Aim 1: AUD subtypes based on symptom profiles

Table 2 shows the model fit information for a one- through seven-class solution. The eight-class model did not converge. As can be seen, the AIC and BIC continued to improve as the number of classes increased and the BLRT was significant for all models when comparing k to k + 1 class solutions, however models with 6 or more classes were not well identified (see percent agreement in Table 2). After comparing class solutions for all classes, a five-class solution was selected based on model identification, interpretability and distinction of classes. Parameter estimates representing the class-specific prevalence of each of the 11 AUD symptoms are presented in Table 3. Interestingly, all classes indicated high (item response probabilities above 0.50) probability of reporting occasions in which they ended up drinking more, or longer than intended. Class 1, ‘Alcohol-Induced Injury’ (25% of all past-year drinkers with AUD) is distinguished from other classes by their proneness of getting into potentially dangerous situations while drinking that could increase their odds of getting hurt. Individuals in Class 2, ‘Highly Problematic, Low Perceived Life Interference’ (21%), were likely to indicate all of the symptoms of AUD, with the exception of those characterized by having an adverse impact on their daily life (i.e. perceived that drinking did not impact their home life, job or school). Class 3, ‘Adverse Effects Only’ (34%), was the largest class and was distinguished by low probability of reporting most symptoms except a very high (1.00) probability of experiencing withdrawal symptoms when the effects of alcohol were wearing off (e.g. shakiness, nausea, racing heart). Individuals in Class 4, ‘Difficulty Cutting Back’ (13%), reported few symptoms of life interference and alcohol-induced injury but indicated a high (1.00) probability of failed attempts to cut back on drinking. Class 5, the smallest (7%) and most severe class, was denoted ‘Highly Problematic’ given their high probability of reporting all symptoms.

Table 2.

Fit statistics for LCA models of adult AUD subgroups

| Class | Percent Agreement | AIC | BIC | ABIC | Entropy | BLRT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100% | 9542.99 | 9615.53 | 9580.58 | 1 | -- |

| 2 | 100% | 3851.70 | 4003.38 | 3930.29 | 0.88 | P = 0.01 |

| 3 | 37% | 3513.30 | 3744.11 | 3632.89 | 0.82 | P = 0.01 |

| 4 | 36% | 3291.45 | 3601.39 | 3452.04 | 0.73 | P = 0.01 |

| 5 | 50% | 3090.80 | 3479.87 | 3292.39 | 0.69 | P = 0.01 |

| 6 | 2% | 2988.24 | 3456.45 | 3230.84 | 0.78 | P = 0.01 |

| 7 | 1% | 2866.06 | 3413.41 | 3149.66 | 0.81 | P = 0.01 |

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criteria, BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria, ABIC = adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria, BLRT = bootstrap likelihood ratio test. Percent agreement refers to the proportion of initial starting values that converged on the maximum likelihood solution.

Table 3.

Item response probabilities for the probability of reporting each symptom given latent class membership

| Class 1: Alcohol-induced injury (25%) | Class 2: Highly problematic, low perceived life- interference (21%) | Class 3: Adverse effects only (34%) | Class 4: Difficulty cutting back (13%) | Class 5: Highly problematic (7%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Drinking more, or longer, than intended | 0.54 | 0.85 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.94 |

| 2. Wanted to cut down or stop drinking, or tried to, but could not | 0.32 | 0.65 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.87 |

| 3. Spent a lot of time drinking or being sick from drinking | 0.11 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.90 |

| 4. Wanted a drink so badly, could not think of anything else | 0.44 | 0.72 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.94 |

| 5. Drinking interfering with home, family, job or school | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.79 |

| 6. Continued to drink despite causing problems with family/friends | 0.26 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.85 |

| 7. Gave up or cut back on activities to drink | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.78 |

| 8. Gotten into risky situations while/after drinking | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.73 |

| 9. Continued to drink despite causing health problems | 0.19 | 0.69 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.99 |

| 10. Increased tolerance for alcohol | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.82 |

| 11. Experience of withdrawal symptoms | 0.17 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.98 |

Note. Probabilities > 0.5 in bold to facilitate interpretation of the latent classes.

Aim 2: age-varying prevalence of AUD subtypes

The age-varying prevalence and corresponding confidence intervals for each AUD latent class are shown in Fig. 1. At any age, the probabilities of the five classes sum to 1.0. The Alcohol-Induced Injury class shows a fairly gradual, linear increase across age with prevalence rates of ~10% at age 18 and peak prevalence at approximately age 58 (26%). The Highly Problematic, Low Perceived Life Interference class was most prevalent in early adulthood (30% at age 18), declined with age (lowest point at approximately age 39 at 15%) and increased to about 21% around age 51. The Adverse Effects Only class was the most prevalent class among young adults with AUD, with peak prevalence of ~40% at age 21. This class was consistently prevalent through around age 42. The prevalence rate declined substantially across older ages, with the lowest rate at ~13% at age 64. The Difficulty Cutting Back class had a similar prevalence across young adulthood and most of adulthood (around 14% to 17%) but had a greatly increased prevalence with ages above 53. This class experienced peak prevalence at approximately age 62 (44%). Finally, the Highly Problematic class was least prevalent across all ages (12% or lower across all ages), with peak prevalence at age 48 (12%).

Fig. 1.

Age-varying probability of five AUD classes. Note. For any given age, estimated probabilities sum to 1.0.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the current study was to advance our understanding of AUD by identifying latent classes of individuals with a past-year AUD and to examine how the prevalence of these groups change across age. By applying novel statistical techniques to a large sample of adults who met criteria for a past-year AUD, we aimed to (a) identify subgroups of individuals with an AUD characterized by unique profiles of symptoms and (b) examine changes in prevalences of these subgroups across age. Overall, we found there were distinct classes of drinkers based on their AUD symptoms and the prevalence of certain classes varied by age.

LCA based on 11 AUD symptoms revealed five unique subgroups of drinkers with a past-year AUD. The Adverse Effects Only class represented our largest latent class. This group was clustered around their experience of withdrawal symptoms after drinking, including a racing heart, nausea or restlessness. It is important to note, however, that withdrawal symptoms ranged in severity, including symptoms that could be attributed to a hangover (e.g. nausea). Participant endorsement of low-level withdrawal symptom severity may explain the discrepancy in experience of withdrawal symptoms without concurrently reporting increased tolerance. Analyses involving latent class prevalence fluctuations across age revealed that this class was most prevalent among young adults and steeply declined after age 40.

The Alcohol-Induced Injury class had a high probability of getting into situations while or after drinking that increased the likelihood of getting hurt, such as driving or swimming while under the influence. The prevalence of this group increased across ages, peaking in prevalence among adults in their 50s. This finding is surprising as risk-taking behavior, such as drunk driving-related behavior, is more prevalent among younger adults, though the prevalence of drivers with BACs above the legal limit involved in fatal crashes has recently decreased in young adult ages and increased in middle-aged and older adults (National Center for Statistics and Analysis, 2017). As scant work has examined risk-taking behavior broadly among individuals with an AUD across the lifespan, additional research is needed to identify reasons for increased prevalence rates around age 50.

Members in the Highly Problematic, Low Perceived Life Interference class had shared characteristics of all symptoms of AUD with the exception of drinking interfering with family, friends, responsibilities or pleasurable activities. It is important to note, however, that these reports were based on perceptions of a lack of life interference. Given that this class highly endorsed experiencing all other symptoms of AUD, it is likely that AUD did impact their life functioning. This class was particularly prevalent in young adulthood. The Difficulty Cutting Back class was comprised of individuals who reported failed attempts to reduce or stop drinking. This class was most common in middle adulthood and was the most prevalent of the five classes among individuals in their 50s and 60s. Finally, the Highly Problematic class was comprised of individuals with a high probability for each of the items. They were the least prevalent class at all ages but were most common among individuals in their late 40s compared to other age groups.

Our study findings add to the literature on the typology of AUD in several important ways. Prior work has also uncovered latent classes of individuals with AUD based on DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria, with some focusing on symptom severity of classes (e.g. Casey et al., 2013; Rinker and Neighbors, 2015; Swift et al., 2016) or multiple characteristics of individuals (e.g. mental health or other substance use disorders; Moss et al., 2007, 2010). In addition to providing further evidence that there are subgroups of individuals with an AUD, we found that the prevalence of these latent classes vary quite significantly by age. Although AUD is most prevalent in young adulthood (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016), it is clear that the behavioral patterns that put someone at risk for AUD are uniquely contingent on age. One possible explanation for these observed age differences is that the features of problematic drinking are likely highly associated with life circumstances. For example, the Highly Problematic, Low Perceived Life Interference class may be particularly prevalent during young adulthood (especially college students) because they generally have a lot of freedom due to few family and occupational responsibilities during this developmental period (Schulenberg and Maggs, 2002). Changes in prevalence rates across age may also reflect the phenomenon of many young adults ‘maturing out’ of heavy drinking after the college years (Jackson et al., 2001; Beseler et al., 2012). Thus, some of the more severe, life-interfering diagnostic characteristics of AUD may be more common among those who did not mature out of heavy drinking early on. This could in part explain the higher prevalence of the Difficulty Cutting Back class in older ages. Similarly, the Adverse Effects Only class peaks in young adulthood and is the most common class during young adulthood because such adverse effects include less severe withdrawal symptoms, such as nausea and other hangover symptoms. Experience of withdrawal symptoms may vary in meaning across age, related to the length of time an individual has had an AUD.

This novel statistical approach of examining changes in prevalence of latent classes across age may be useful for future research in several ways. Future research may benefit from building on our cross-sectional findings by using prospective data to model within-person changes in latent class membership across age. For example, this approach could be applied to better understand which subgroups are most at risk for failing to mature out of heavy drinking after college. Also, our knowledge on this topic may be advanced by examining age-varying predictors of membership in latent classes at each age, as this could highlight the risk factors that should be targeted in interventions at certain ages. Patrick and colleagues (2011) found that motivations for drinking change across ages 18–30 and differentially correspond to use. It is possible that many other psychosocial and environmental factors contribute to age differences in AUD typology throughout adulthood, which may inform targets for intervention within each age category.

Findings from our study indicate that there is heterogeneity in AUD, and that the prevalence of these different latent classes of AUD vary with age across adulthood. Because of the heterogeneity across individuals with AUD, recent calls have been made for developing and advancing personalized intervention approaches (Litten et al., 2015). Our findings support this need for individually tailored intervention efforts and add that age appears to be a critical factor by which we can adapt interventions. Findings also have implications for screening for AUD. The nature of AUD seems to shift with age, and our results suggest that there are important aspects to screen for or hone in on in treatment at each age. Future longitudinal research is needed to determine the trajectory of class membership. For instance, although the Adverse Effects class is high in young adulthood, prevalence of this class declines across age. It remains unclear whether and which individuals in this class transition or age out of having an AUD or transition into a more severe class. A cohort-sequential design would help elucidate these questions. Also, although the Highly Problematic class was the smallest subgroup, it is important to note that the prevalence was relatively stable across age. Future longitudinal research is needed to determine if membership in this group is stable across age within-individuals and what factors predict class membership. As this class had high probabilities of reporting each of the 11 symptoms, prevention and intervention efforts are most needed for this subgroup of individuals.

The current study had many strengths, including its large sample size, representativeness and sampling procedure; however, there are several limitations that should be taken into consideration. Primarily, our data on AUD are derived from self-report surveys. Self-reported AUD symptoms could be subjected to recall biases or social desirability concerns. Also, the NESARC study design is cross-sectional, which limits inferences of causality or change within an individual over time and introduces confounding of age and cohort. Future research may benefit from using a prospective design to examine the way AUD subgroup membership changes across one’s lifetime. Moreover, although the final five-class solution had better model identification than other classes, entropy for the five-class solution was lower than other classes (0.69), which corresponds to item response probabilities falling a bit further from values of 0 or 1. Finally, our study examined AUD among only adults in the USA. Differences in AUD in terms of the prevalence by age cohort and in the nature of class compositions may be different in countries outside the USA (e.g. Mäkelä et al., 2006; Aresi et al., 2018). Potential cultural differences in AUD should be a focus of future research. Despite limitations, this study added to the literature by demonstrating that there are distinct subgroups of individuals who have an AUD, and that the prevalences of these groups vary across age. Future work building toward personalized intervention should consider the specific symptoms that may be most crucial to focus on when developing both universal and individually tailored prevention and intervention efforts.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This manuscript was prepared using a limited access dataset obtained from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and does not reflect the opinions or views of NIAAA or the US Government.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health [P50 DA039838 and R01 DA039854]. The NIDA did not have any role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; writing the report and the decision to submit the report for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Aresi G, Cleveland MJ, Marta E, et al. (2018) Patterns of alcohol use in Italian emerging adults: a latent class analysis study. Alcohol Alcohol 53:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa AI, Homer JF, Fleming MF, et al. (2008) Alcohol consumption and health among elders. Gerontologist 48:622–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beseler CL, Taylor LA, Kraemer DT, et al. (2012) A latent class analysis of DSM-IV alcohol use disorder criteria and binge drinking in undergraduates. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36:153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey M, Adamson G, Stringer M (2013) Empirical derived AUD subtypes in the US general population: a latent class analysis. Addict Behav 38:2782–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2016) 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Dziak JJ, Lanza ST (2016). LcaBootstrap SAS macro users' guide (Version 4.0) University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State. http://methodology.psu.edu

- Grant BF, Chu A, Sigman R, et al. (2014) Source and Accuracy Statement: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, et al. (2015) The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5): reliability of substance use and psychiatric disorder modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 148:27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, et al. (2001) Transitioning into and out of large-effect drinking in young adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol 110:378–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JM, Buu A, Zucker RA (2016) Longitudinal phenotypes for alcoholism: heterogeneity of course, early identifiers, and life course correlates. Dev Psychopathol 28:1531–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SP, Sher KJ (2015) Limits of current approaches to diagnosis severity based on criterion counts: an example with DSM-5 alcohol use disorder. Clin Psychol Sci 3:819–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Dziak JJ, Huang L, et al. 2015. PROC LCA & PROC LTA users’ guide (Version 1.3.2) University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State. http://methodology.psu.edu.

- Li R, Dziak JD, Tan X, et al. 2015. TVEM (time-varying effect model) SAS macro users’ guide (Version 3.1.0) University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State. http://methodology.psu.edu

- Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Falk DE, et al. (2015) Heterogeneity of alcohol use disorder: understanding mechanisms to advance personalized treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:579–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä P, Gmel G, Grittner U, et al. (2006) Drinking patterns and their gender differences in Europe. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl 41:i8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi H-Y (2007) Subtypes of alcohol dependence in a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 91:149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi H-Y (2010) Prospective follow-up of empirically derived alcohol dependence subtypes in wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC): Recovery status, alcohol use disorders and diagnostic criteria, alcohol consumption behavior, health status, and treatment seeking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34:1073–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Statistics and Analysis (2017). Alcohol-impaired driving: 2016 data (Traffic Safety Facts. Report No. DOT HS 812 450). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- Patra J, Taylor B, Irving H, et al. (2010) Alcohol consumption and the risk of morbidity and mortality for different stroke types—a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 18:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, et al. (2011) Age-related changes in reasons for using alcohol and marijuana from ages 18 to 30 in a national sample. Psychol Addict Behav 25:330–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Shield KD, Roerecke M, et al. (2016) Modelling the impact of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular disease mortality for comparative risk assessments: an overview. BMC Public Health 16:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Taylor B, Mohapatra S, et al. (2010) Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev 29:437–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker DV, Neighbors C (2015) Latent class analysis of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria among heavy-drinking college students. J Subst Abuse Treat 57:81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M, Rehm J (2014) Chronic heavy drinking and ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 1:e000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, et al. (2015) 2010 National and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. Am J Prev Med 49:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL (2002) A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 14:54–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shireman EM, Steinley D, Sher K (2015) Sex differences in the latent class structure of alcohol use disorder: does (dis)aggregation of indicators matter? Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 23:291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GW, Shevlin M (2008) Patterns of alcohol consumption and related behaviour in Great Britain: a latent class analysis of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT). Alcohol Alcohol 43:590–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift W, Slade T, Carragher N, et al. (2016) Adolescent predictors of a typology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder symptoms in young adults derived by latent class analysis using data from an Australian cohort study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 77:757–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, et al. (2012) A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychol Methods 17:61–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Hingson R (2013) The burden of alcohol use: excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res 35:201–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.