Abstract

Analysing multiple evidence sources is often feasible only via a modular approach, with separate submodels specified for smaller components of the available evidence. Here we introduce a generic framework that enables fully Bayesian analysis in this setting. We propose a generic method for forming a suitable joint model when joining submodels, and a convenient computational algorithm for fitting this joint model in stages, rather than as a single, monolithic model. The approach also enables splitting of large joint models into smaller submodels, allowing inference for the original joint model to be conducted via our multi-stage algorithm. We motivate and demonstrate our approach through two examples: joining components of an evidence synthesis of A/H1N1 influenza, and splitting a large ecology model.

Keywords: model integration, Markov combination, Bayesian melding, evidence synthesis

1. Introduction

The increasing availability of large amounts of diverse types of data in all scientific fields has prompted an explosion in applications of methods that combine multiple sources of evidence using (Bayesian) graphical models (for example, Moran and Clark, 2011; Commenges and Hejblum, 2012; Shubin et al., 2016; Birrell et al., 2016). Such evidence synthesis methods have several advantages (Ades and Sutton, 2006; Welton et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2015): resulting estimates are typically more precise, due to the increased amount of information; they are consistent with all available knowledge; and the risk of potential biases introduced if estimation relies on a ‘best quality’ subset is minimised.

However, dealing with joint models of several sources of evidence, including data and expert opinion, may be inferentially imprudent, computationally challenging, or even infeasible. It is often sensible to take a modular approach, where separate submodels are specified for smaller components of the available data, facilitating computation and, importantly, allowing insight into the influence of each submodel on the joint model inference (Green et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2009). These submodels can originate in two ways: either by first specifying submodels that, in a Bayesian framework, should be joined in a single model to allow all information and uncertainty to be fully propagated; or as a result of splitting an existing joint model.

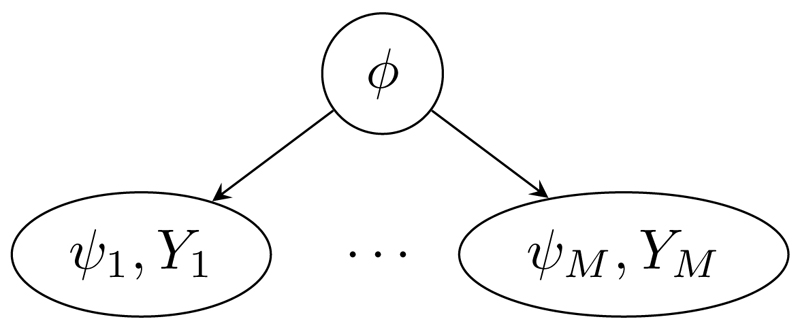

Formally, consider M probability submodels pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym), m = 1, . . . , M, for submodel-specific multivariate parameters ψm and observable random variables Ym, as well as a multivariate parameter ϕ common to all submodels that acts as a ‘link’ between the submodels. The problem is then to join the submodels into a single model pcomb(ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψM, Y1, . . . , YM) so that the posterior distributions for the link parameter ϕ and the submodel-specific parameters ψm account for all observations and uncertainty. A suitable joint model for a collection of submodels naturally arises in some contexts from standard model constructs, such as a hierarchical model (Figure 1). However, it is not immediately clear how to form such a joint model when either: the submodels are not expressed in a form conditional upon the link parameter ϕ, particularly if the link parameter is a non-invertible deterministic function of the other parameters; or the prior marginal distributions pm(ϕ), m = 1, . . . , M, for the link parameter ϕ differ in the submodels. In applied research, convenient approximate two-stage approaches have been widely used, where one submodel is fitted and an approximation of the resulting posterior is provided to a second submodel (Jackson et al., 2009; Presanis et al., 2014). However, the joint model that is implied by such an approach is unclear (Eddy et al., 1992; Ades and Sutton, 2006).

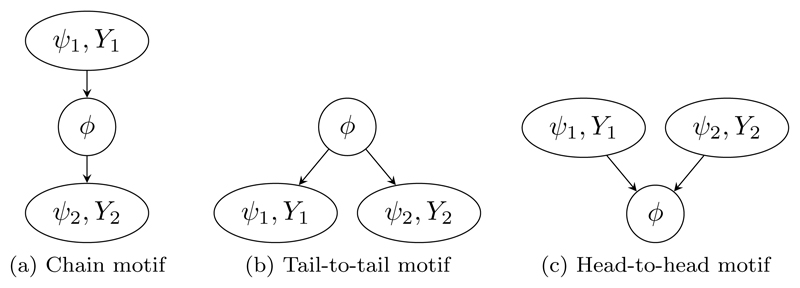

Figure 1.

DAG representation of a joint hierarchical model linking M submodels.

Conversely, suppose a joint model p(ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψM, Y1, . . . , YM) exists that needs splitting into M submodels pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym), m = 1, . . . , M. The submodels should be faithful to the original model in the sense that joining the submodels results in the original model. In some contexts, suitable submodels arise naturally from the structure of the joint model, resulting in splitting strategies used implicitly in the context of hierarchical models (Lunn et al., 2013a; Tom et al., 2010; Liang and Weiss, 2007) and of tall data (Scott et al., 2016; Neiswanger et al., 2014). However, neither the general conditions stipulating when splitting is permissible nor a general framework for splitting a model are immediately clear.

In this paper we introduce Markov melding, a simple, generic approach for joining and splitting models that clarifies and generalises various proposals made in the literature under the umbrella of one theoretical framework. Markov melding builds on the theory of Markov combination (Dawid and Lauritzen, 1993) and super Markov combination (Massa and Lauritzen, 2010; Massa and Riccomagno, 2017) and combines it with ideas from Bayesian melding (Poole and Raftery, 2000), enabling evidence synthesis (Ades and Sutton, 2006; Welton et al., 2012) and model expansion (Draper, 1995) in realistic applied settings. Markov combination is a framework for combining submodels when the prior marginal distributions pm(ϕ), m = 1, . . . , M, are identical. If the prior marginal distributions differ, the super Markov combination family of combined models can be formed, each member of which adopts any one of the prior marginal distributions pm(ϕ) in a combined model. However, in applied contexts, discarding all but one of the prior marginal distributions would usually be unjustifiable, so we propose instead to adopt a pooled prior marginal distribution that reflects all prior marginal distributions. Markov melding also accounts for contexts where the link parameter ϕ is a non-invertible deterministic function of other parameters in a submodel. When joining submodels, Markov melding aims to preserve the original submodels as faithfully as possible, and, in particular, always preserves the submodel-specific conditional distributions pm(ψm, Ym | ϕ) for all m. Note that, while Markov melding is defined for any collection of submodels, the results may be misleading if any evidence components (priors, submodels and data) strongly conflict (Presanis et al., 2013; Gåsemyr and Natvig, 2009). Such conflict should be investigated and resolved, for example through bias modelling (Turner et al., 2009), before proceeding with the synthesis. In terms of splitting, the Markov melding framework proposed here clarifies the conditions required and the general framework in which to conduct model splitting, facilitating the modular approach advocated above. Notably, we generalise existing tall data splitting approaches (Scott et al., 2016; Neiswanger et al., 2014) for independent, identically distributed data to other types of data.

Finally, we also develop an algorithm for fitting the Markov melded model in stages, for both joining and splitting models. This algorithm extends naturally that employed in Lunn et al. (2013a) and is closely related to those proposed in Liang and Weiss (2007) and Tom et al. (2010).

The paper is organised as follows: in Section 2 we introduce some examples motivating this work; Section 3 provides the conceptual framework underlying our approach; inferential and computational aspects of the approach are presented in Section 4; Section 5 gives details and results for the motivating examples; we conclude with a discussion and suggestions for further work in Section 6.

2. Motivating examples

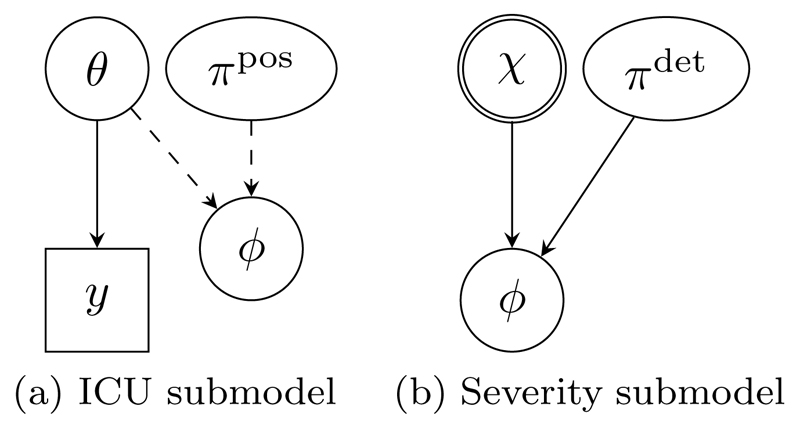

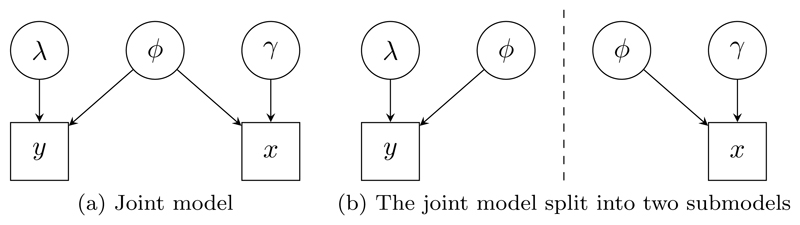

We motivate and demonstrate our framework for joining and splitting models with two examples, for which we provide here a brief high-level outline. We show how Markov melding applies in each case in Section 3.3; and provide full details and results in Section 5. For both examples, as in the rest of the paper, we use directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to represent the dependence structure between variables in a model (Figures 2 and 3). Each variable in the model is represented by a node with rectangular nodes denoting observed variables and links between the nodes indicating direct dependencies. Stochastic (distributional) dependencies are represented by solid lines and deterministic (logical) relationships by dashed lines. The joint distribution of all nodes is the product of the conditional distributions of each node given its direct parents, and conditional independence relationships can be read from the graph (Lauritzen, 1996).

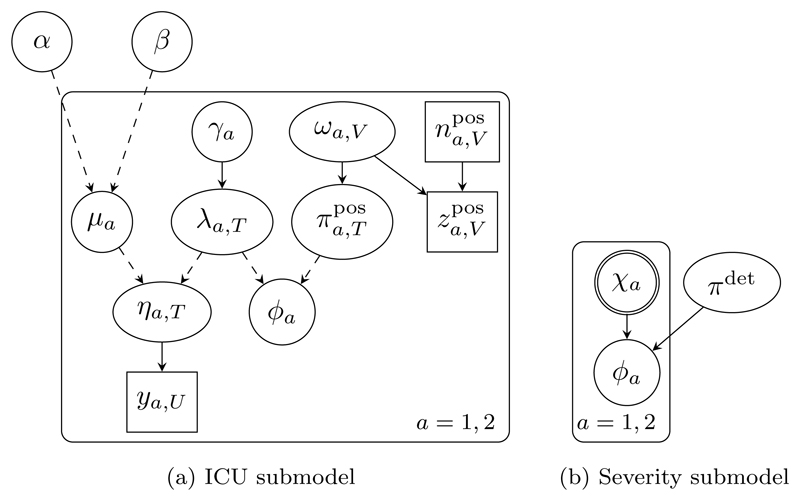

Figure 2.

High-level DAG representations of the influenza submodels. The double circle denotes the (highly) informative prior for χ, reflecting data from the full severity submodel that is omitted here. Detailed DAGs of these submodels are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 3.

High-level DAG representations of the ecology models. Detailed DAG representations of these models are shown in Figure 9.

2.1. Joining: A/H1N1 influenza evidence synthesis

Public health responses to influenza outbreaks rely on knowledge of severity: the probability that an infection results in a severe event such as hospitalisation or death. One method to estimate severity is by combining estimates of cumulative numbers of severe events with estimates of cumulative numbers of infections obtained from synthesizing different data sources. This approach is adopted in Presanis et al. (2014) for the A/H1N1 pandemic, where information from intensive care units (ICU) is integrated with several other sources. Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of the submodels used for each evidence component. A crucial ingredient is the cumulative number of ICU admissions for the A/H1N1 strain, χ. A lower bound ϕ for χ is estimable through an immigration-death model governed by transition rates θ, from time-dependent (weekly) prevalence data y on suspected ‘flu cases in ICU (Figure 2(a)). The ϕ of Figure 2(a) is a deterministic function (a sum) of latent quantities involving θ and other parameters πpos. Indirect aggregate evidence on χ is also available from a severity submodel (Figure 2(b)), whose complexity is summarised here by an informative prior on χ. The lower bound ϕ is related to χ through a binomial model with probability parameter πdet.

The two submodels imply two different prior models for the link quantity ϕ. A further complication is that the deterministic function connecting ϕ to the ICU submodel parameters is a sum of products, which is not invertible, preventing the ICU submodel from being expressed conditional on ϕ. Presanis et al. (2014) therefore transferred information between the two separate submodels via an approximate approach (see Section 4.3 for details). We show in this paper how Markov melding can be used to join the two submodels formally into a single joint model, making all the assumptions involved explicit. We also explain the relationship between our approach and the approximate approach.

2.2. Splitting: large ecology model

As an example of splitting a large DAG model we consider a joint model (Besbeas et al., 2002) for two distinct sources of data about British Lapwings (Vanellus vanellus). These data sources are primarily collected to inform different aspects of studies of the birds: census-type data provide a measure of breeding population size, while mark-recapture-recovery data provide estimates of the annual survival probability of the birds via observations of the survival of uniquely marked individuals. These data are related and a joint model allows inference to account for all information available. In the joint Bayesian model of Brooks et al. (2004) (Figure 3(a)), the mark-recapture-recovery data y are modelled in terms of the recovery rate λ, and the survival rate ϕ for birds; and the census data x are modelled in terms of the survival rate ϕ, and the productivity rate γ of adult female birds. The joint model links the data sources using the common survival rate parameter ϕ.

Brooks et al. (2004) considered fitting the census and mark-recapture-recovery models both separately and jointly using standard Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms, but considering the joint model simultaneously is cumbersome and MCMC convergence is slow. We describe in this paper how, through Markov melding, inference from such a joint model can be carried out in stages after splitting the model into two separate submodels (Figure 3(b)), circumventing the need to directly fit the joint model in a single MCMC procedure. The multi-stage fitting process is more computationally efficient, and gives insight into the contribution of each submodel to the joint model.

3. Conceptual framework

3.1. Joining models

To combine probabilistic models in a principled way, we propose Markov melding as an extension of Markov combination, which has been introduced by Dawid and Lauritzen (1993) and discussed extensively with generalisations and applications in Massa and Lauritzen (2010) and Massa and Riccomagno (2017).

Let p denote either a probability distribution for discrete random variables or a probability density for continuous variables (we assume such a density exists). In both cases we talk of p interchangeably as a probability or probability distribution and we express conditional probabilities as p(ψ | ϕ) = p(ψ, ϕ)/p(ϕ), where p(ϕ) > 0. We will assume that when conditioning on a variable its distribution has support in the relevant region. For random variables X1, X2 and X3, X1 ⫫ X2 | X3 means that X1 and X2 are conditionally independent given X3.

Markov combination

Dawid and Lauritzen (1993) define the submodels pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym), m = 1, . . . , M, as consistent in the link parameter ϕ if the prior marginal distributions pm(ϕ) = p(ϕ) are the same for all m. They define the Markov combination pcomb of M consistent submodels as the joint model

| (1) |

By construction, model (1) assumes that the submodels are conditionally-independent: (ψm, Ym) ⫫ (ψℓ, Yℓ) | ϕ for m ≠ ℓ (see Figure 1). All prior marginal distributions and submodel-specific conditional distributions, given the link parameter, are preserved: pcomb(ϕ, ψm, Ym) = pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym) and pcomb(ψm, Ym | ϕ) = pm(ψm, Ym | ϕ) for all m. Furthermore, the model has maximal entropy among the set of distributions with this marginal preservation property, and so can be viewed as the least constrained among such distributions (Massa and Lauritzen, 2010). Only prior marginals are preserved in Markov combinations: the posterior distributions of ϕ and any ψℓ under the Markov combination model account for all data Ym, m = 1, . . . , M, rather than just the submodel-specific data Yℓ, and are not preserved.

Markov melding

If the submodels are not consistent in their link parameter ϕ, that is, if the prior marginal distributions p1(ϕ), . . . , pM(ϕ) of the link parameter differ, a Markov combination cannot be formed directly. However, the original submodels pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym), m = 1, . . . , M, can be altered so that the marginals p1(ϕ), . . . , pM(ϕ) for the link parameter become consistent. This is achieved by a procedure we term marginal replacement, where a new model prepl,m(ϕ, ψm, Ym) is formed by replacing the marginal distribution pm(ϕ) of ϕ in the original model pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym) by a new marginal distribution ppool(ϕ):

| (2) |

where the pooled density ppool(ϕ) = g(p1(ϕ), . . . , pM(ϕ)) is a function g of the individual prior marginal densities. Here, and in what follows, we assume that such a pooled density exists, that g has been chosen such that ∫ ppool(ϕ) dϕ = 1, and that ppool reflects an appropriate summary of the individual marginal distributions; we discuss options below.

Since prepl,m(ϕ, ψm, Ym), m = 1, . . . , M, are consistent in the link parameter ϕ (that is, they all have the same prior marginal ppool(ϕ)), we can form their Markov combination

| (3) |

We term this construction Markov melding of the submodels pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym) with pooled density ppool(ϕ) = g(p1(ϕ), . . . , pM(ϕ)), which amounts to applying the Markov combination (1) to submodels satisfying the consistency condition after marginal replacement as in (2). The submodel-specific conditional distributions, given the link parameter, are preserved in the Markov melded model: pmeld(ψm, Ym | ϕ) = pm(ψm, Ym | ϕ) for all m. However, in contrast to Markov combination, the prior marginal distributions pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym) will, in general, not be preserved in the Markov melded model. Once the new model pmeld(ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψM, Y1, . . . , YM) has been formed by Markov melding, posterior inference conditioning on the data Y1 = y1, . . . , YM = yM can be performed (see Section 4).

If ppool equals pm for a specific submodel m ∈ {1, . . . , M} then, in the terminology of Massa and Lauritzen (2010), marginal replacement (2) forms a member of a maximally extended family and Markov melding (3) forms a member of the super Markov combination family. That is, rather than allowing a pooled prior marginal distribution ppool that can reflect all the prior marginal distributions p1(ϕ), . . . , pM(ϕ), maximally extended families and super Markov combination require the use of a single one of the original prior marginal distributions; see Supplementary Material A for details.

By extending a similar argument used in Poole and Raftery (2000), it can be shown that marginal replacement has the attractive property that prepl,m minimises the Kullback-Leibler divergence DKL of a distribution q(ϕ, ψ, Y) to pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym) under the constraint that the marginals on ϕ agree, q(ϕ) = ppool(ϕ):

Marginal replacement can also be interpreted as a generalisation of Bayesian updating in the light of new information. Details are provided in Supplementary Material B.

Markov melding with deterministic variables

Care is required when some of the dependencies in a submodel are deterministic, as in the example in Section 2.1. The considerations are identical to those for Bayesian melding (Poole and Raftery, 2000), where priors on the input and output of deterministic functions are combined. Specifically, assume the k-dimensional link parameter ϕ is deterministically related to a ℓ-dimensional parameter θ, k ≤ ℓ, in a model p(ϕ, θ, ψ, Y). The probability model is effectively given by p(θ, ψ, Y) and ϕ follows an induced distribution. We assume ϕ is exclusively a deterministic function ϕ(θ) of the parameter θ.

To apply Markov melding, we need to ensure that the prior marginal distribution on ϕ is well defined, and that we can apply marginal replacement to ϕ = ϕ(θ). We must assume that ϕ(θ) is an invertible function or, in the case of k < ℓ, that ϕ(θ) can be expanded into an invertible function ϕe(θ) = (ϕ(θ), t(θ)), with a ℓ − k dimensional deterministic function t(θ). We denote the inverse function by θ(ϕ, t). The function ϕe induces a probability distribution on (ϕ, t, ψ, Y) which can be represented as

where Jθ(ϕ, t) is the Jacobian determinant for the transformation θ(ϕ, t). The marginal distribution on ϕ can now be obtained as p(ϕ) = ∫ p(ϕ, t, ψ, Y) dt dψ dY. We show in Supplementary Material C that p(ϕ) is independent of the chosen parametric extension t(θ) and so is well defined, and that we can apply marginal replacement, as defined by (2), to replace p(ϕ) with ppool(ϕ):

| (4) |

Markov melding with prepl(θ, ψ, Y) can now be applied as in (3).

Pooling marginal distributions

The pooling function g determines the prior marginal distributions pmeld(ϕ, ψm, Ym), which, in general, will not match those in the original submodels. It must, therefore, be chosen subjectively, ensuring that the pooled density ppool(ϕ) appropriately represents prior knowledge of the link parameter ϕ. Various standard pooling functions have been suggested in the multiple expert elicitation literature (see, for example, Clemen and Winkler, 1999; O’Hagan et al., 2006). The difference here is that we propose to pool prior marginal distributions of submodels, rather than directly-specified priors. A simple option is linear pooling,

where w = (w1, . . . , wM)⊤, with wm ≥ 0 to weight the submodel priors. An alternative is log pooling,

with wm ≥ 0, a logarithmic version of the linear pooling (for reasons why logarithmic pooling might be attractive see Supplementary Material D). A special case of log pooling is product of experts (PoE) pooling (Hinton, 2002) when wm = 1 for all m

in which equal weight is given to each submodel prior. A further special case of linear or log pooling is dictatorial pooling ppool(ϕ) = pm(ϕ) when one submodel m ∈ {1, . . . , M} is considered authoritative1. We shall assume throughout this paper that the weights w are a fixed quantity, chosen subjectively, in contrast to some of the power prior literature (Neuenschwander et al., 2009), where attempts have been made to treat the weight w as an unknown parameter.

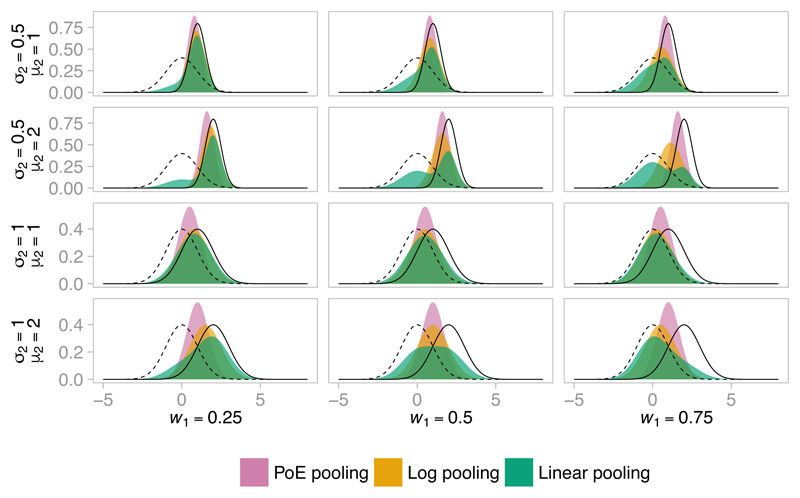

Figure 4 shows the pooled density when combining two normal distributions under three different pooling functions with three choices of weights. The PoE approach is arguably the least intuitive pooling function due to the rather concentrated combined distribution implied. However, the required computation is greatly simplified (see Section 4), and so if (and only if) PoE adequately represents prior beliefs then PoE pooling is an attractive option. The choice of pooling function is particularly important when there is some disagreement between the priors, but if there is substantial conflict between submodel priors we do not recommend the use of Markov melding, as mentioned above.

Figure 4.

Pooled densities under PoE, log and linear pooling, with w1 = 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75 (and w2 = 1 − w1), formed by pooling a N(0, 1) density (---) and a N(µ2, ) density (—) with µ2 = 1, 2, 4, and σ2 = 0.5, 1.

3.2. Splitting models

We may want to split up a larger model, for example, for computational efficiency or to understand the influence of each submodel on the joint model. In this case we want to split a large joint model p(ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψM, Y1, . . . , YM) into M submodels pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym), m = 1, . . . , M, in such a way that joining the submodels using Markov melding recovers the original, joint model. If (ψm, Ym) ⫫ (ψℓ, Yℓ) | ϕ for m ≠ ℓ in the original model, then suitable submodels are

where p1(ϕ), . . . , pM(ϕ) are new prior marginal distributions. These marginal distributions and the pooling function g can chosen freely to enable efficient computation, provided that the pooled distribution ppool(ϕ) = g(p1(ϕ), . . . , pM(ϕ)) is the same as the original marginal distribution p(ϕ). An obvious choice is pm(ϕ) = p(ϕ)1/M with PoE pooling, but there are many other options. For example, PoE pooling is suitable for any factorisation of p(ϕ) into M factors.

Note that a splitting strategy based on Markov melding is suitable only if (ψm, Ym) ⫫ (ψℓ, Yℓ) | ϕ for m ≠ ℓ, that is, conditioning on the link variable ϕ makes the parts that are intended for splitting conditionally independent.

Figure 5 shows a few stylised situations with M = 2 where splitting for computational purposes might be desirable. The joint distributions for all models is p(ϕ, ψ1, ψ2, Y1, Y2). The model in Figure 5(a) can be split into p1(ϕ, ψ1, Y1) = p(ϕ, Y1 | ψ1)p(ψ1) and p2(ϕ, ψ2, Y2) = p(ψ2, Y2 | ϕ)p2(ϕ), with a new prior distribution p2(ϕ), which could be different and computationally simpler than p(ϕ) = ∫ p(ϕ, Y1 | ψ1)p(ψ1) dψ1 dY1. Markov melding, with dictatorial pooling ppool(ϕ) = p1(ϕ), results in

leading to the original model, regardless of the choice of p2(ϕ). The case in Figure 5(b) is similar to the example in Section 2.2 (see Section 3.3 for a definition of splitting in this case). Note that in Figures 5(a) and 5(b), the dependencies between the nodes can include deterministic (logical) dependence, provided (ψ1, Y1) ⫫ (ψ2, Y2) | ϕ, as usual. The case in Figure 5(c) cannot be split into p1(ϕ, ψ1, Y1) and p2(ϕ, ψ2, Y2) by Markov melding model splitting because (ψ1, Y1) ⫫̸ (ψ2, Y2) | ϕ.

Figure 5.

DAG representations of stylised situations where model splitting might be desirable. Splitting the joint model is possible in (a) and (b), but not in (c).

3.3. Markov melding in the motivating examples

Joining: A/H1N1 influenza evidence synthesis

Markov melding involves joining the ICU submodel (Figure 2(a)) with density p1(ϕ, θ, πpos, Y), where ϕ is a deterministic function of θ and πpos, and the severity submodel (Figure 2(b)) with density p2(ϕ, χ, πdet). These submodels involve independently-collected data from different surveillance systems, and so it is reasonable to assume conditional independence. Replacing the marginal distribution of ϕ with pooled density ppool(ϕ) in the ICU submodel, using (4), and in the severity submodel, using (2), and then applying Markov melding, as in (3), results in

| (5) |

where Y1 = Y, ψ1 = {θ, πpos}, Y2 = Ø and ψ2 = {χ, πdet} in the notation of (3).

Splitting: large ecology model

The original, joint model (Figure 3(a)), with density p(ϕ, λ, γ, Y, X), can be split into separate submodels (Figure 3(b)) with densities p1(ϕ, λ, Y) and p2(ϕ, γ, X). Provided the priors p1(ϕ) and p2(ϕ) in the separate submodels are such that ppool(ϕ) = g(p1(ϕ), p2(ϕ)) equals the original marginal distribution p(ϕ), for some choice of pooling function g, then Markov melding the submodels recovers the joint model:

with ψ1 = λ, Y1 = Y, ψ2 = γ, Y2 = X in the notation of (3).

4. Inference and computation

The joint posterior distribution, given data Ym = ym, m = 1, . . . M, under the Markov melded model in (3) is

| (6) |

The degree of difficulty of inference for this posterior distribution depends on the specification of the submodels. Our focus is settings in which, considered separately, each of the original collection of submodels is amenable to inference by standard Monte Carlo methods (for example, Robert and Casella, 2004).

In Section 4.1 we first consider a standard Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampler, but when the constituent submodels are complex, this sampler may be cumbersome and slow. We thus propose a multi-stage Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampler, in which inference for the full Markov melded model is generated iteratively in stages, starting with standard inference on one of the submodels. This latter sampling scheme enables a convenient modular approach to inference. Both approaches, in general, require the marginal prior densities pm(ϕ) of the link parameter under each submodel, m = 1, . . . , M, which will not usually be analytically tractable. In Section 4.2 we discuss approaches to estimating these densities, although there is no need to estimate them if PoE pooling is chosen. In Section 4.3 we show how approximate approaches, such as those used by Presanis et al. (2014), relate to the Markov melded model.

4.1. Metropolis-Hastings samplers

A general Metropolis-Hastings sampler for the posterior distribution (6) can be constructed in the usual way. Candidate values for each parameter of the Markov melded model are drawn from a proposal distribution based on the current values (ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψM) of the Markov chain. The candidate values are accepted with probability min(1, r), where r is in the form

where, with common normalising constants cancelled, the target-to-proposal density ratio is

| (7) |

Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampler

A particular form of the above general sampler is a Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampling scheme (Müller, 1991), in which samples are drawn from the full conditional distribution of each latent parameter ψ1, . . . , ψM, and then the link parameter ϕ in turn.

Latent parameter updates Markov melding does not introduce any extra complexities in sampling the parameters ψm in each submodel m = 1, . . . , M (conditional on the link parameter ϕ) beyond those inherent to the original submodels, considered separately. Typically, they can be sampled using standard algorithms. For instance, a Metropolis-Hastings algorithm, in which we draw a candidate value from a proposal distribution based upon the current value ψm, will be feasible whenever the corresponding algorithm is feasible for estimation of the posterior distribution of the mth submodel alone. In this case, since terms involving marginal densities for the link parameter ϕ in (6) cancel, the target-to-proposal density ratio in (7) simplifies to

This target-to-proposal density ratio is identical to that required for a Metropolis-Hastings update for the parameter ψm, conditional on the link parameter ϕ, when the mth submodel alone is the target distribution.

Link parameter updates To update the link parameters, a candidate value ϕ⋆ is drawn from an appropriate proposal distribution q(ϕ⋆ | ϕ), based upon the current value ϕ, and is accepted according to the target-to-proposal density ratio

| (8) |

When the prior marginal distributions pm(ϕ) or ppool(ϕ) are not analytically tractable, we propose to use an approximation p̂m(ϕ) in their place, calculated using the methods described in Section 4.2. Note that, under PoE pooling, the terms involving the marginal distributions for the link parameter ϕ cancel in (8), leaving

removing the need to estimate the marginal prior distribution for the link parameter ϕ.

Multi-stage Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampler

When the constituent submodels are complex, an alternative, multi-stage approach may be computationally preferable to the Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampler. The multi-stage approach generalises the two stage approach in Lunn et al. (2013a). We assume a factorisation of the pooled prior A default factorisation for any pooling function sets ppool,m(ϕ) = ppool(ϕ)1/M, but there may be more computationally-efficient factorisations. For example, when PoE pooling is used, the factorisation with ppool,m(ϕ) = pm(ϕ) is more computationally efficient, as we describe below. The aim then is to sample, iteratively in stages ℓ = 1, . . . , M, from

| (9) |

Since pmeld,M (ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψM | y1, . . . , yM) = pmeld(ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψM | y1, . . . , yM), after M stages the samples obtained reflect the posterior distribution (6) of the full Markov melded model. Note that each pm(ϕ) (and thus also ppool(ϕ)) can be estimated from the submodels in advance and independently of the following sampling scheme, as we describe in Section 4.2.

Stage 1. We obtain H1 samples drawn from pmeld,1(ϕ, ψ1 | y1). The most appropriate method for obtaining such samples depends on the nature of the submodel p1(ϕ, ψ1, Y1); typically, standard Monte Carlo methods, such as MCMC, will be suitable.

Stage ℓ. After we have sampled up to stage ℓ − 1 from (9), we construct a Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampler for stage ℓ for the parameters (ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψℓ) given data (y1, . . . , yℓ). The parameter ψℓ is updated, conditional on the link parameter ϕ and parameters ψ1, . . . , ψℓ−1 using a standard algorithm, such as a Metropolis-Hastings sampler, with a target-to-proposal density ratio

We use the samples from stage ℓ−1 as a proposal distribution when updating the parameters ψ1, . . . , ψℓ−1 and the link parameter ϕ. Specifically, we draw an index d uniformly at random from {1, . . . , Hℓ−1}, and set so that

The attraction of this particular proposal distribution is the resulting cancellation of likelihood terms for the first ℓ − 1 submodels in the target-to-proposal density ratio,

| (10) |

meaning this update step can be performed quickly. Once sampling in stage ℓ has converged, samples are obtained for use in stage ℓ + 1.

The density ratio (10) does not depend on parameters ψ1, . . . , ψℓ−1, so if interest focuses entirely on the parameters (ϕ, ψℓ) then ψ1, . . . , ψℓ−1 can be ignored in stage ℓ of the multi-stage sampling: they do not need to be monitored or updated by the sampling algorithm. The multi-stage sampler is nevertheless still sampling from the joint target distribution pmeld,ℓ(ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψℓ | y1, . . . , yℓ). Stage ℓ is influencing the acceptance or rejection of samples of pmeld,ℓ−1(ϕ, ψ1, . . . , ψℓ−1 | y1, . . . , yℓ−1) from the previous stage, thus adjusting this distribution according to the requirements of the joint model.

In general, evaluation of ratio (10) requires estimates of the prior marginal distribution of the link parameter under the ℓth submodel, which can be obtained as described in Section 4.2. However, if PoE pooling is used and ppool,m(ϕ) = pm(ϕ), m = 1, . . . , M, the ratio simplifies to meaning that no estimates of the marginal distribution are required.

4.2. Estimating marginal distributions

The prior marginal densities pm(ϕ) of the link parameter under each of the M submodels are central to Markov melding, and in particular are required to evaluate the acceptance probability of proposals within the MCMC samplers we proposed above. However, these marginals are not generally analytically tractable, except when the prior distribution pm(ϕ) is directly-specified as a standard, tractable distribution, such as when ϕ appears as a founder node in a DAG representation of the submodel. When not available analytically, we can estimate the marginal density pm(ϕ) for each submodel m by kernel density estimation (Henderson and Parmeter, 2015) with samples drawn from pm(ϕ) = ∫∫ pm(ϕ, ψm, Ym) dψm dYm by standard (forward) Monte Carlo. Care is required if ϕ has high dimension because the curse of dimensionality applies to kernel density estimation; see Section 6 for further discussion.

4.3. Normal two-stage approximation method

Approximate approaches for joining submodels are widely used in applied research. In this section, we show that approximate inference for the Markov melded model formed by joining submodels (with PoE pooling) can be produced using a standard normal approximation approach.

Consider the case when the Markov melded model pmeld(ϕ, ψ1, ψ2, Y1, Y2) is formed by joining M = 2 submodels p1(ϕ, ψ1, Y1) and p2(ϕ, ψ2, Y2). Suppose that ψ1 is not a parameter of interest in the posterior distribution, so that it can be integrated over

| (11) |

An approximate two stage sampler that mimics the multi-stage sampler (above) can then be constructed for this marginal distribution.

Stage 1 Fit the submodel p1(ϕ, ψ1, Y1) to obtain posterior samples from p1(ϕ | Y1), and approximate the posterior by a (multivariate) normal distribution with mean µ̂ and covariance Σ̂. With pN denoting the probability density function for a (multivariate) normal distribution,

Stage 2 Since p1(ϕ, Y1) ∝ p1(ϕ | Y1) ≈ pN (μ̂ | ϕ, Σ̂), we obtain an approximation for (11) by replacing p1(ϕ | Y1) by pN (µ̂ | ϕ, Σ̂).

This two-stage approximate approach is commonly used in practice (see Section 6) in the form pmeld(ϕ, ψ2, Y1, Y2) ≈ c pN (μ̂ | ϕ, Σ̂) p2(ϕ, ψ2, Y2), with c a data dependent constant. In this case the likelihood of the second submodel is modified by a factor pN (μ̂ | ϕ, Σ̂) (in a DAG representation a dependency of the constant μ̂ on ϕ and the constant Σ̂ is added). This approach can be viewed as approximate Markov melding with PoE pooling, in which one submodel is represented by a normal approximation.

If, instead of PoE pooling, one wishes to regard the marginal p2(ϕ) on the link variable ϕ as authoritative and thus fully retain it, dictatorial pooling ppool(ϕ) = p2(ϕ) leads to the variant

where µ̂ and Σ̂0 are an estimate of the mean and covariance of the prior marginal p1(ϕ), which can be obtained at stage one in parallel to the posterior by sampling from the prior submodel, and

Adjusting according to µ̂0 and Σ̂0 removes the prior p1(ϕ) from approximate joint model.

5. Results

5.1. Joining: A/H1N1 influenza evidence synthesis

Figure 6 shows DAG representations of the two submodels outlined in Section 2.1.

Figure 6.

DAG representations of the submodels of A/H1N1 influenza. Repeated variables are enclosed by a rounded rectangle, with the label denoting the range of repetition. For simplicity the time domain is suppressed: parameters with subscripts T, U and V are collections of parameters across the time range denoted by the subscript. For example, ya,U = {ya,t : t ∈ U}.

ICU submodel

The main data source in the ICU submodel is prevalence-type data from the Department of Health’s Winter Watch scheme (Department of Health, 2011), which records the total number of patients in all ICUs in England with suspected pandemic A/H1N1 influenza infection. Weekly observations ya,t taken at days t ∈ U = {8, 15, 22, . . . , 78} for age group a ∈ {1, 2} (children and adults respectively) are available between December 2010 and February 2011. To estimate the link parameter ϕ = (ϕa) = (ϕ1, ϕ2), that is, the cumulative number of ICU admissions over the period of observation t ∈ T = {1, . . . , 78}, from such prevalence data requires an immigration-death model for the system of ICU admission and exits from ICU. Assume that new ICU admissions follow an inhomogeneous Poisson process with rate λa,t at time t, and the length of stay in ICU is exponentially distributed with rate µa. Then the number of patients admitted up to time t who are still present in ICU at time t follows a thinned inhomogeneous Poisson process and the observed number of prevalent patients is ya,t ~ Po(ηa,t), a ∈ {1, 2}, t ∈ U, with expectation, under a discretised formulation with daily time steps, given by We assume ηa,1 = 0 to enforce the assumption that no patients with suspected ‘flu were in ICU a week before observations began.

The product of the expected new admissions of suspected cases λa,t and the proportion positive for A/H1N1 gives the expected number of confirmed new admissions on day t. The link parameter ϕa is the uninvertible sum of these products over time:

We model the proportion positive using weekly virological positivity data from the sentinel laboratory surveillance system Data Mart (Public Health England, 2014), which records the number of A/H1N1-positive swabs out of the total number tested during week v ∈ V = {1, . . . , 11} in age group a ∈ {1, 2}. We assume a uniform prior for the true positivity, where v = 1 for t = 1, . . . , 14 and v = ⌊(t − 1)/7⌋ for t = 15, . . . , 78, and where the lower bound ωa,v is informed by a binomial model for the positivity data: For the expected new admissions λa,t, we assume a random-walk prior with log(λa,1) ~ Unif(0, 250) and for t = 2, . . . , 78, with γa ~ Unif(0.1, 2.7). For the length of ICU stays we assume constant age-group specific exit rates µ1 = exp(−α) and µ2 = exp(−{α + β}), with α ~ N(2.7058, 0.07882) and β ~ N(−0.4969, 0.20482) (Presanis et al., 2014).

Severity submodel

We consider a simplified version of the full, complex severity submodel in Presanis et al. (2014). The Winter Watch ICU data are only available for a portion of the time of the ‘third wave’ of the A/H1N1 pandemic, and so the cumulative number of confirmed new admissions ϕa from the ICU submodel is a lower bound for the true number χa of ICU admissions during the third wave. We thus assume ϕa ~ Bin(χa, πdet), a ∈ {1, 2}, where πdet is the age-constant detection probability, to which we assign a Beta(6, 4) prior. We incorporate the remaining evidence in the full severity submodel of Presanis et al. (2014) via informative priors χ1 ~ Lognormal(4.93, 0.172) and χ2 ~ Lognormal(7.71, 0.232).

Markov melded model

We joined the submodels as in (5). We considered linear and log pooling with pooling weight w1 = 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75 (and w2 = 1 − w1), and PoE pooling.

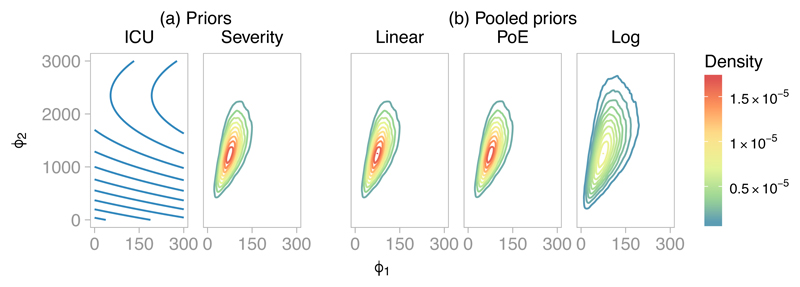

We estimated the marginal priors for ϕ = (ϕ1, ϕ2) under the ICU and severity submodels using kernel density estimation with a bivariate t-distribution kernel, using 5 × 104 independent draws, sampled from the corresponding submodel by forward Monte Carlo. The marginal priors are shown in Figure 7(a). Note that the ICU submodel prior for ϕ is extremely flat, whereas the severity submodel prior is concentrated on a small part of the parameter space. The combined density using each of the pooling functions (with w1 = w2 = 0.5) is shown in Figure 7(b). Linear and PoE pooling in this case lead to similar densities, whereas the log pooling prior is more dispersed.

Figure 7.

Prior distributions for ϕa, the cumulative number of confirmed new admissions in age group a, in the A/H1N1 influenza evidence synthesis: (a) under the ICU and severity submodels; (b) pooled priors under three pooling functions with w1 = w2 = 0.5.

We then estimated, in stage one, the posterior distribution of the link parameter ϕ under the ICU submodel alone. We drew 5 million iterations from the ICU submodel using JAGS (Plummer, 2015b), retaining every 100th iteration, after discarding 5 × 104 iterations as burn-in. In stage two, for the Markov melded models under linear, log and PoE pooling, we drew 2 × 106 samples using the multi-stage Metropolis-within-Gibbs sampler, with the first 104 samples discarded as burn-in.

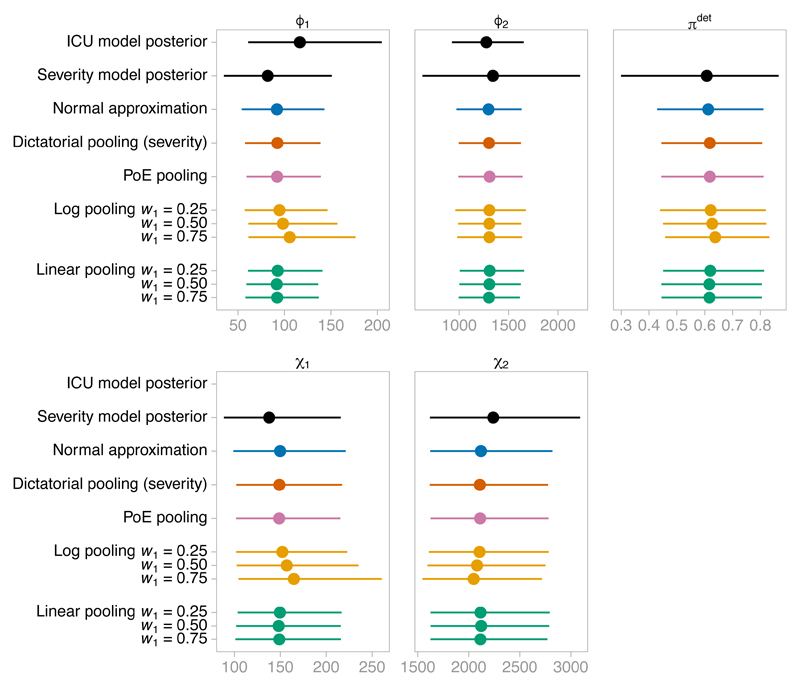

Figure 8 shows the results. There is a notable reduction in uncertainty in the posteriors from Markov melding compared to the ICU submodel posterior, especially in ϕ1, demonstrating the benefit of joining the submodels. In the adult age group (a = 2), the Markov melding results are robust to the choice of pooling function and pooling weight: the likelihood from the ICU submodel dominates over the pooled prior. There is considerable agreement between the various approaches in the child age group (a = 1) as well, although the choice of pooling weight has some influence on the upper tail under log pooling. As anticipated by Section 4.3, the normal approximation (fitted using OpenBUGS) and PoE pooling posteriors are close, due to the near normality of the ICU posterior distribution.

Figure 8.

Medians and 95% credible intervals for: the posterior distribution for the link parameters ϕ1 and ϕ2 under the ICU submodel; the prior distribution for each parameter under the severity submodel; the posterior distribution for each parameter according to the normal approximation and the Markov melded model under each pooling function. The x-axis shows number of individuals, except for πdet, which shows probabilities.

5.2. Splitting: large ecology model

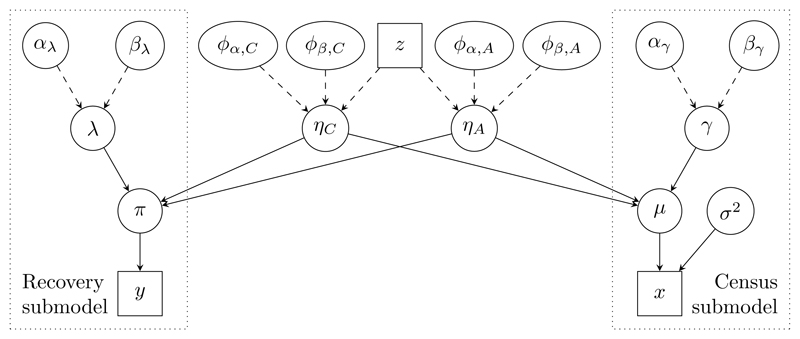

Figure 9 is a DAG representation of the full, joint model outlined in Section 2.2.

Figure 9.

DAG representation of the joint ecology model. The recovery and census submodels are connected via the common parameter ϕ = (ϕα,C, ϕα,A, ϕβ,C, ϕβ,A). For simplicity the time domain is suppressed: y, x, π, µ, λ, ηC, ηA, γ and z represent the collection of all quantities sharing the same variable name. For example, µ = {µG,t : G ∈ {C, A}, t = 3, . . . , 36}.

Mark-recapture-recovery data

Mark-recapture-recovery data yt1,t2 record the number of ringed birds released before May in year t1 = 1, . . . , 35, and recovered (dead) in the 12 months up to April in year t2 = t1 + 1, . . . , 36. The years correspond to observations for releases from 1963 (t = 1) to 1997 and recoveries from 1964 to 1998. The number of birds yt1,37 released in year t1 and never recovered is also available. We assume

We model the probability πt1,t2 of recovery in year t2 following release in year t1 in terms of the recovery rate λt, and the survival rates ηC,t and ηA,t for immature (1 year old) and breeding (2 years or older) birds, respectively, up to April of year t:

The recovery rate is the probability that a bird that dies in year t is recovered. The probability of a bird released in year t1 being never recovered is

Census data

We assume that the observed census-type data xt, which are available for 1965 (t = 3) to 1998, account for only breeding birds and that there is no emigration. We model the census data via the true number of breeding females µA,t and immature females µC,t, and the productivity rate γt, the average number of female offspring per breeding female in year t, which could be greater than 1. Specifically we assume for t = 3, . . . , 36

with the observation variance σ2 assumed constant.

Regression models and prior distributions

We model the parameters ηG,t, λt and γt with regression models, with zt denoting the (observed) number of frost days in year t.

We place lognormal priors on the number of immature females µC,2 and breeding females µA,2 in the year prior to our data series, with scale parameter 1 and location parameters µC = 200 and µA = 1000 respectively. We assume σ2 ~ Inv-Gam(0.001, 0.001) a priori, and independent N(0, 102) prior distributions for all 8 regression parameters (ϕα,C, ϕα,A, αλ, αγ, ϕβ,C, ϕβ,A, βλ, βγ).

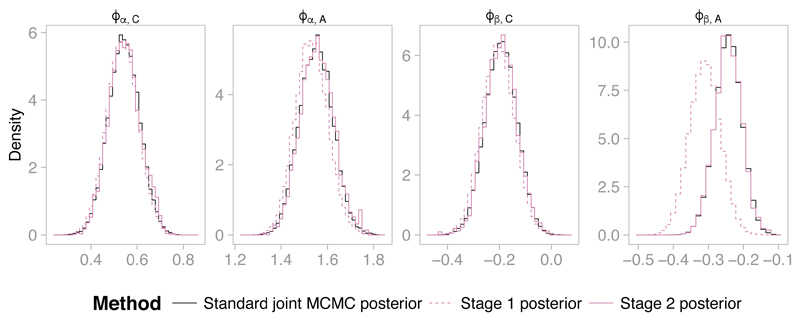

Results

We split the joint model, as described in Section 3.3, into two components: the mark-recapture-recovery submodel and the census submodel. Denote by Ω0 = (ηC, ηA, ϕα,C, ϕα,A, ϕβ,C, ϕβ,A) the parameters shared by both submodels and by Ω1 = (π, λ, αλ, βλ) the parameters specific to the recovery submodel. Under both the mark-recapture-recovery submodel (stage one) and the census submodel (stage two), we use independent normal priors, with mean 0 and standard deviation for each component ϕα,C, ϕα,A, ϕβ,C and ϕβ,A of the link parameter. These priors were chosen so that PoE pooling of these priors results in the original prior for the link parameters under the joint model.

In stage one we drew samples from the posterior distribution p1(Ω1, Ω0 | y) under the recovery submodel, and retained these samples for use as a proposal distribution in stage two, in which we drew samples under the full joint model. In stage one, we drew 2.5 × 105 MCMC iterations from the posterior distribution of the mark-recapture-recovery submodel, taking 7 hours on a single core of an Intel Xeon E5-2620 2.0GHz CPU. In stage two, we discarded all but every 100th iteration, leaving 2.5 × 105 MCMC iterations for inference. This took hours.

Figure 10 shows the results. We compare the two-stage estimates to the estimates of the joint distribution based upon 6 × 105 MCMC iterations (retaining every 10th iteration) drawn using a standard (one stage) MCMC sampler, which took 22 hours to run in OpenBUGS. We regard these results as the ‘gold standard’ that we aim to match with the two stage sampling approach. The components of the link parameters ϕα,C and ϕβ,C corresponding to the immature birds have posterior distributions that closely agree under the joint model and mark-recapture-recovery submodel alone, but there are differences in the parameters corresponding to mature birds. In particular there is a sizeable difference for the regression parameter ϕβ,A, which is estimated to be notably higher under the joint model than under the mark-recapture-recovery submodel alone. The two-stage approach accurately captures this shift (Figure 10, right-hand panel). The similarity of ϕα,C, ϕα,A and ϕβ,C in the stage 1 posterior (recovery model) and the stage 2 posterior implies that the census submodel contains little information about these parameters. In contrast, the census submodel does contain information about the regression parameter ϕβ,A describing the relationship between the survival rate of adult birds and the number of frost days. The census information suggests that ϕβ,A should be less negative than implied by the recovery information, implying that adult survival rate decreases only slightly in harsher winters.

Figure 10.

Histograms of the posterior densities of the link parameters ϕα,C, ϕα,A, ϕβ,C and ϕβ,A under the recovery submodel (Stage 1), and under the full joint model, as estimated by Stage 2 of the two stage sampler and by a standard MCMC sampler for the joint model.

6. Further work and discussion

We have presented a unifying view and a generic method for joining and splitting probabilistic submodels that share a common variable. We have extended the notions of Markov combination and super Markov combination to permit pooling of prior marginal distributions, enabling a principled approach to joining models in realistic applied settings, assuming that there is not strong conflict between evidence components and that it is reasonable to assume that the submodels are conditionally independent. We also introduced a computational algorithm that allows inference for submodels to be efficiently conducted in stages, when considering either joining or splitting models. The remainder of this section discusses related work, computational issues and alternative approaches.

6.1. Related work

The key idea for a melding approach can be attributed to Poole and Raftery (2000), but their presentation focuses on a limited set of models and is tied up with a deterministic link parameter ϕ. This slightly obscures the key issues that we present more generally in Section 3, where we clearly separate issues relating to marginal replacement from issues related to deterministic transformation of random variables. A further influence is Markov combination of submodels with consistent marginal distributions (Dawid and Lauritzen, 1993), and the concept of super Markov combination (Massa and Lauritzen, 2010) of a pair of families of submodels, in which submodel-specific conditionals and link-parameter marginal distributions (which must be marginals of members of one of the original families) are “mixed-and-matched” to form a family of possible combined models. Markov melding extends these approaches by permitting, via the pooling function, the marginal distribution of the link parameter to reflect the prior marginal distributions of all submodels, rather than just one. Markov combination forms part of the literature on decomposable graphical models, where a key concept is the separator, a subset of variables that splits the model into two parts that are independent conditional on the separator. Separators correspond to link variables in Markov melding. The rich literature on decomposable graphs and corresponding algorithms, such as junction tree algorithms (Lauritzen, 1996), suggests extensions of Markov melding to a series of link variables (separators) for joining several submodels into chain or tree formations.

Evidence synthesis models (Eddy et al., 1992; Jackson et al., 2009; Albert et al., 2011; Commenges and Hejblum, 2012) often employ the approximate approach of summarising the results of a first-stage submodel via a Gaussian or other distribution, for use in a second-stage submodel as a likelihood term. We demonstrated in Section 4.3 that this approach is an approximation to Markov melding under PoE pooling, therefore justifying the approximation. Similar approximations are widely used in standard and network meta-analysis (for example, Hasselblad et al., 1992; Ades and Sutton, 2006; Welton et al., 2008). Similarly, in more general hierarchical models, splitting models to make inference faster or easier has previously been considered (Liang and Weiss, 2007; Tom et al., 2010; Lunn et al., 2013a). In this setting, posterior inference is first obtained from independent unit-specific submodels, with flat, independent priors replacing all hierarchical priors in the joint model. Inference for the joint model is recovered in stage two through Markov melding of these unit-specific submodels with dictatorial pooling, so that only the hierarchical prior is reflected in the final results. This can make cross-validation more convenient (Goudie et al., 2015). Splitting models into conditionally independent components at a set of separator or link parameters is also a key aspect of cross-validatory posterior predictive methods, including “node-splitting”, for assessing conflict across subsets of evidence (Presanis et al., 2013; Gåsemyr and Natvig, 2009). Markov melding may provide a natural, computationally-efficient approach for systematic conflict assessment (Presanis et al., 2016).

Our framework can also be viewed as encapsulating a range of approaches proposed in the big data literature for handling a large number of observations (‘tall data’). With tall data it may be infeasible even to store all of the data on a single computer, nevermind evaluate functions depending on the whole dataset thousands of times, as needed in MCMC. Instead, a divide-and-conquer approach can be taken, in which the original exchangeable data y are partitioned into B batches y1, . . . , yB, each of which contains few enough observations that standard statistical methods can be applied without undue trouble. The key observation is that the full posterior distribution p(ϕ | y) can be split into a number of submodel posteriors pb(ϕ | yb) ∝ p(yb | ϕ)p(ϕ)1/B, b = 1, . . . , B. This is a form of model splitting (Section 3.2), with PoE pooling and the original prior apportioned equally among the batches. Various approaches for integrating the batch-specific posteriors to approximate the overall posterior have been proposed (Huang and Gelman, 2005; Scott et al., 2016; Neiswanger et al., 2014; Wang and Dunson, 2013; Bardenet et al., 2017; Minsker et al., 2017). However, this literature has so far only considered independent, identically distributed data, whereas we have considered more general models and data.

6.2. Computational challenges

In our examples, the link variable ϕ is comparatively low dimensional and simple kernel density estimation using a multivariate t-distribution kernel proved sufficient. Moreover, the results were robust with respect to the choice of kernel and kernel bandwidth. For higher-dimensional link variables more care in the choice of kernel estimation method might be required (Henderson and Parmeter, 2015), or, alternatively, we might wish to estimate the ratio of densities directly to improve stability (Sugiyama et al., 2012).

The multi-stage sampler (Section 4.1) broadly falls into the category of a sequential Monte Carlo sampler (Doucet et al., 2013), as described in Supplementary Material E. While the Markov melding model is invariant to the ordering of the submodels used (assuming the pooling function is also), the efficiency of the multi-stage algorithm may not be in practice, due to the need for there to be sufficient stage one samples in the appropriate region. If two submodels contain an approximately equal amount of nonconflicting information, then the ordering is unlikely to be important. In other settings, more care may be required. For example, suppose submodel M1 contains considerably more information than M2. If stage one uses M1, then the stage one posterior may be so precise that it is unable to be adjusted for the extra information in M2. In contrast, if M2 is used first, then the estimate of the posterior distribution may be very coarse, due to a lack of samples in the central part of the posterior distribution. Further research will be needed to identify the best ordering to adopt in general.

6.3. Alternative approaches

We obtained consistency in the link parameter ϕ, as required by Markov combination, through marginal replacement (Section 3.1). This approach assumes the priors differ in substance across submodels. Alternatively, as we outline in Supplementary Material F, we could assume that the priors differ only due to different scalings in each submodel, and so can be made consistent through rescaling, similar to when deriving multivariate distributions from copulas (Durante and Sempi, 2010). Yet another approach is a supra-Bayesian approach (Lindley et al., 1979; Leonelli, 2015), in which the decision maker models the experts’ opinions.

The prior pooling approach considered within our framework includes a judgement as to how to weight the different submodels. Various other methods have been proposed for weighting evidence, including the cut operator (Lunn et al., 2013b; Plummer, 2015a); the power prior approach in clinical trials (for example, Neuenschwander et al., 2009); and modularisation in the computer models literature (Liu et al., 2009). Further research is required to investigate the relationship of Markov melding to other weighting approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council [programme codes MC_UU_00002/2, MC_UU_00002/11 and MC_UU_00002/1]. We are grateful to Ian White, Sylvia Richardson, Brian Tom, Michael Sweeting, Paul Kirk, Adrian Raftery, and the 2015 Armitage lecturers (Leonhard Held and Michael Höhle) for helpful discussions of this work; and to the referees and editors for insightful comments that led to an improved manuscript. We also thank colleagues at Public Health England for providing data.

Footnotes

Dictatorial pooling corresponds to left (or right) composition in the terminology of Massa and Lauritzen (2010), and for M = 2 their upper Markov combination is the family comprising two distributions namely the two possible directions for dictatorial pooling.

References

- Ades AE, Sutton AJ. Multiparameter evidence synthesis in epidemiology and medical decision-making: current approaches. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2006;169(1):5–35. 1, 2, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Albert I, Espié E, de Valk H, Denis J-B. A Bayesian evidence synthesis for estimating Campylobacteriosis prevalence. Risk Analysis. 2011;31(7):1141–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01572.x. 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardenet R, Doucet A, Holmes C. On Markov chain Monte Carlo methods for tall data. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2017;18(47):1–43. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Besbeas P, Freeman SN, Morgan BJT, Catchpole EA. Integrating mark–recapture–recovery and census data to estimate animal abundance and demographic parameters. Biometrics. 2002;58(3):540–547. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00540.x. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell PJ, De Angelis D, Wernisch L, Tom BD, Roberts GO, Pebody RG. Efficient real-time monitoring of an emerging influenza epidemic: how feasible? arXiv:1608.05292. 2016 doi: 10.1214/19-AOAS1278. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SP, King R, Morgan BJT. A Bayesian approach to combining animal abundance and demographic data. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation. 2004;27(1):515–529. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Clemen RT, Winkler RL. Combining probability distributions from experts in risk analysis. Risk Analysis. 1999;19(2):187–203. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.202015. 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commenges D, Hejblum BP. Evidence synthesis through a degradation model applied to myocardial infarction. Lifetime Data Analysis. 2012;19(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10985-012-9227-3. 1, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawid AP, Lauritzen SL. Hyper Markov laws in the statistical analysis of decomposable graphical models. Annals of Statistics. 1993;21(3):1272–1317. 2, 5, 6, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Department of Health Winter Watch. 2011 http://winterwatch.dh.gov.uk. 16.

- Doucet A, de Freitas N, Gordon N, editors. Sequential Monte Carlo Methods in Practice. New York: Springer Science & Business Media: 2013. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Draper D. Assessment and propagation of model uncertainty. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1995;57(1):45–97. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Durante F, Sempi C. Copula theory: an introduction. In: Jaworski P, Durante F, Härdle WK, Rychlik T, editors. Copula Theory and its Applications. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2010. pp. 3–31. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy DM, Hasselblad V, Shachter R. Meta-Analysis by the Confidence Profile Method. London: Academic Press; 1992. 2, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Gåsemyr J, Natvig B. Extensions of a conflict measure of inconsistencies in Bayesian hierarchical models. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 2009;36(4):822–838. 3, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Goudie RJB, Hovorka R, Murphy HR, Lunn D. Rapid model exploration for complex hierarchical data: application to pharmacokinetics of insulin aspart. Statistics in Medicine. 2015;34(23):3144–3158. doi: 10.1002/sim.6536. 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PJ, Hjort NL, Richardson S. Introducing highly structured stochastic systems. In: Green PJ, Hjort NL, Richardson S, editors. Highly Structured Stochastic Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 1–12. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselblad V, Eddy DM, Kotchmar DJ. Synthesis of environmental evidence: nitrogen dioxide epidemiology studies. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 1992;42(5):662–671. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1992.10467018. 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson DJ, Parmeter CF. Applied Nonparametric Econometrics. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2015. 15, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton GE. Training products of experts by minimizing contrastive divergence. Neural computation. 2002;14(8):1771–1800. doi: 10.1162/089976602760128018. 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Gelman A. Sampling for Bayesian computation with large datasets. Working paper. 2005 24. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CH, Best NG, Richardson S. Bayesian graphical models for regression on multiple data sets with different variables. Biostatistics. 2009;10(2):335–351. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn041. 2, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CH, Jit M, Sharples LD, De Angelis D. Calibration of complex models through Bayesian evidence synthesis. Medical Decision Making. 2015;35(2):148–161. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13493143. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen SL. Graphical Models. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1996. 3, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Leonelli M. Bayesian decision support in complex modular systems: an algebraic and graphical approach. Ph.D. thesis, University of Warwick; UK: 2015. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Liang L-J, Weiss RE. A hierarchical semiparametric regression model for combining HIV-1 phylogenetic analyses using iterative reweighting algorithms. Biometrics. 2007;63(3):733–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00753.x. 2, 3, 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley DV, Tversky A, Brown RV. On the reconciliation of probability assessments. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (General) 1979;142(2):146–180. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Bayarri MJ, Berger JO. Modularization in Bayesian analysis, with emphasis on analysis of computer models. Bayesian Analysis. 2009;4(1):119–150. 1, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Lunn D, Barrett J, Sweeting M, Thompson S. Fully Bayesian hierarchical modelling in two stages, with application to meta-analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics) 2013a;62(4):551–572. doi: 10.1111/rssc.12007. 2, 3, 13, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn D, Jackson C, Best N, Thomas A, Spiegelhalter D. The BUGS Book: A Practical Introduction to Bayesian Analysis. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2013b. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Massa MS, Lauritzen SL. Combining statistical models. In: Viana MAG, Wynn HP, editors. Contemporary Mathematics: Algebraic Methods in Statistics and Probability II. 2010. pp. 239–260. 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Massa MS, Riccomagno E. Algebraic representations of Gaussian Markov combinations. Bernoulli. 2017;23(1):626–644. 2, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Minsker S, Srivastava S, Lin L, Dunson DB. Robust and scalable Bayes via a median of subset posterior measures. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2017;18(124):1–40. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Moran EV, Clark JS. Estimating seed and pollen movement in a monoecious plant: a hierarchical Bayesian approach integrating genetic and ecological data. Molecular Ecology. 2011;20(6):1248–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05019.x. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P. A generic approach to posterior integration and Gibbs sampling. Technical Report 91-09, Purdue University; 1991. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Neiswanger W, Wang C, Xing EP. Asymptotically exact, embarrassingly parallel MCMC. Proceedings of the Thirtieth Conference Annual Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (UAI-14); Corvallis, Oregon. AUAI Press; 2014. pp. 623–632. 2, 3, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Neuenschwander B, Branson M, Spiegelhalter DJ. A note on the power prior. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28(28):3562–3566. doi: 10.1002/sim.3722. 9, 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hagan A, Buck CE, Daneshkhah A, Eiser JR, Garthwaite PH, Jenkinson DJ, Oakley JE, Rakow T. Uncertain Judgements: Eliciting Experts’ Probabilities. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M. Cuts in Bayesian graphical models. Statistics and Computing. 2015a;25(1):37–43. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M. JAGS Version 4.0.1 user manual. 2015b 18. [Google Scholar]

- Poole D, Raftery AE. Inference for deterministic simulation models: The Bayesian melding approach. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2000;95(452):1244–1255. 2, 7, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Presanis AM, Ohlssen D, Cui K, Rosinska M, De Angelis D. Conflict diagnostics for evidence synthesis in a multiple testing framework. arXiv:1702.07304. 2016 23. [Google Scholar]

- Presanis AM, Ohlssen D, Spiegelhalter DJ, De Angelis D. Conflict diagnostics in directed acyclic graphs, with applications in Bayesian evidence synthesis. Statistical Science. 2013;28(3):376–397. 3, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Presanis AM, Pebody RG, Birrell PJ, Tom BDM, Green HK, Durnall H, Fleming D, De Angelis D. Synthesising evidence to estimate pandemic (2009) A/H1N1 influenza severity in 2009–2011. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2014;8(4):2378–2403. 2, 4, 12, 17, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. Sources of UK flu data: influenza surveillance in the UK. 2014 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/sources-of-uk-flu-data-influenza-surveillance-in-the-uk 17.

- Robert CP, Casella G. Monte Carlo Statistical Methods. New York: Springer; 2004. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Scott SL, Blocker AW, Bonassi FV, Chipman HA, George EI, McCulloch RE. Bayes and big data: The consensus Monte Carlo algorithm. International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management. 2016;11(2):78–88. 2, 3, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Shubin M, Lebedev A, Lyytikäinen O, Auranen K. Revealing the true incidence of pandemic A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza in Finland during the first two seasons—An analysis based on a dynamic transmission model. PLOS Computational Biology. 2016;12(3):e1004803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004803. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama M, Suzuki T, Kanamori T. Density Ratio Estimation in Machine Learning. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2012. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Tom JA, Sinsheimer JS, Suchard MA. Reuse, recycle, reweigh: combating influenza through efficient sequential Bayesian computation for massive data. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2010;4(4):1722–1748. doi: 10.1214/10-AOAS349. 2, 3, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Smith GCS, Thompson SG. Bias modelling in evidence synthesis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2009;172(1):21–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00547.x. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Dunson DB. Parallel MCMC via Weierstrass Sampler. arXiv:1312.4605. 2013 24. [Google Scholar]

- Welton NJ, Cooper NJ, Ades AE, Lu G, Sutton AJ. Mixed treatment comparison with multiple outcomes reported inconsistently across trials: Evaluation of antivirals for treatment of influenza A and B. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(27):5620–5639. doi: 10.1002/sim.3377. 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Cooper NJ, Abrams KR, Ades A. Evidence Synthesis for Decision Making in Healthcare. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.