Abstract

Background and Aims

Cultured cell suspensions have been the preferred model to study the apoplast as well as to monitor metabolic and cell cycle-related changes. Previous work showed that methyl jasmonate (MeJA) inhibits leaf growth in a CORONATINE INSENSITIVE 1 (COI1)-dependent manner, with COI1 being the jasmonate (JA) receptor. Here, the effect of COI1 overexpression on the growth of stably transformed arabidopsis cell cultures is described.

Methods

Time-course experiments were carried out to analyse gene expression, and protein and metabolite levels.

Key Results

Both MeJA treatment and the overexpression of COI1 modify growth, by altering cell proliferation and expansion. DNA content as well as transcript patterns of cell cycle and cell wall remodelling markers were altered. COI1 overexpression also increases the protein levels of OLIGOGALACTURONIDE OXIDASE 1, BETA-GLUCOSIDASE/ENDOGLUCANASES and POLYGALACTURONASE INHIBITING PROTEIN2, reinforcing the role of COI1 in mediating defence responses and highlighting a link between cell wall loosening and growth regulation. Moreover, changes in the levels of the primary metabolites alanine, serine and succinic acid of MeJA-treated Arabidopsis cell cultures were observed. In addition, COI1 overexpression positively affects the availability of metabolites such as β-alanine, threonic acid, putrescine, glucose and myo-inositol, thereby providing a connection between JA-inhibited growth and stress responses.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the understanding of the regulation of growth and the production of metabolic resources by JAs and COI1. This will have important implications in dissecting the complex relationships between hormonal and cell wall signalling in plants. The work also provides tools to uncover novel mechanisms co-ordinating cell division and post-mitotic cell expansion in the absence of organ developmental control.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, cell suspension culture, COI1, jasmonate, cell cycle, cell wall proteins, primary metabolism, stress signalling

INTRODUCTION

Jasmonate (JA) signalling, perceived by the CORONATINE INSENSITIVE 1 (COI1) receptor (Chini et al., 2007; Thines et al., 2007; Fonseca et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2009), regulates developmental, abiotic and biotic stresses that among others, involve the cell wall (Balbi and Devoto, 2008; Howe and Jander, 2008; Gális et al., 2009; Wu and Baldwin, 2010; Denness et al., 2011; Noir et al., 2013; Wasternack and Hause, 2013). The plant cell wall is a highly dynamic structure and an essential component involved in cell morphogenesis and plant–pathogen interactions (Cosgrove, 2005; Hématy et al., 2009; Szymanski and Cosgrove, 2009). Phytohormones such as abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), JAs and ethylene, as well as reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulate the cross-talk between biotic and abiotic stress responses (reviewed by Fujita et al., 2006; Bolwell and Daudi, 2009). JA, SA and ethylene are produced as a consequence of reduced cellulose biosynthesis associated with changes in cell wall structure and composition and increased pathogen resistance (Ellis and Turner, 2002; Cano-Delgado et al., 2003; Manfield et al., 2004; Hernandez-Blanco et al., 2007; Hamann et al., 2009). ROS- and JA-dependent processes regulate lignin biosynthesis following damage (Denness et al., 2011). Plant cell cultures have been subjected to elicitation by biotic stressors and/or transiently transformed to study host defence (Kuchitsu et al., 1997; Ferrando et al., 2000; Day et al., 2001; Navarro, 2004). O’Brien et al. (2012) showed, using arabidopsis cell suspension cultures, that the cell wall peroxidase genes PRX33 and PRX34 are required for microbe-associated molecular pattern (MAMP)-activated responses.

Cell cultures of different plants such as tobacco Bright Yellow 2 (BY-2), Catharantus roseus and arabidopsis have been previously subjected to treatment with methyl jasmonate (MeJA) followed by targeted metabolite analysis (Goossens et al., 2003; Wolucka et al., 2005; Fukusaki et al., 2006; Rischer et al., 2006). Extensive metabolic changes in primary and secondary metabolism were caused by MeJA treatment of Medicago truncatula cultures (Broeckling et al., 2005). A recent study provided molecular evidence suggesting that NtCOI1 functions upstream of the transcription factor NtMYB305 playing a role in co-ordinating plant primary carbohydrate metabolism and related physiological processes in tobacco (Wang et al., 2014). For the most part, studies on metabolic profiling of arabidopsis cell cultures in response to JAs have focused on particular classes of metabolites such as monolignols (Pauwels et al., 2008). Studies on the effect of MeJA on the cell cycle have also been carried out on actively dividing and synchronized cell cultures (Światek et al., 2002, 2004; Pauwels et al., 2008). Despite the obvious limitations due to lack of specialized organ responses, plant cell culture represents an abundant source of plant cell wall material and hence is still the system of choice to analyse related signalling.

Devoto et al. (2002) generated epitope-tagged COI1-overexpressing arabidopsis plants and transiently transformed cell suspensions to demonstrate that COI1 interacts with SKP1-like proteins and the histone deacetylase HDA6, forming an SCFCOI1 complex. In this work, Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspension cultures have been stably transformed with COI1, and this system was used to analyse the effects of JA signalling on cell growth and on the production of cell wall proteins and metabolites.

Our findings frame a case study for the stable transformation of arabidopsis cell suspensions identifying COI1-dependent changes in cell wall proteins, cell division and expansion, as well as availability of primary metabolites. The effect of the stable overexpression of COI1 on the apoplastic proteome and on the growth dynamics of cell suspensions was analysed with the aid of flow cytometry and transcript analysis of cell cycle and cell wall remodelling markers. The results are corroborated by in planta studies. Changes in primary metabolism of cell suspensions were determined by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis identifying COI1- as well as MeJA-dependent metabolic changes. It is shown here that the overexpression of COI1 affects polyamine and inositol metabolism and possibly glycolysis. The possible significance of MeJA-dependent changes on the level of succinic acid, an intermediate of the Krebs cycle, as well as other primary metabolites is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Arabidopsis coi1-16B (AT2G39940) (Ellis and Turner, 2002), cleaned from the pen2 mutation (Westphal et al., 2008; Noir et al., 2013), A. thaliana T2 lines expressing COI1 as a haemagglutinin (HA) C-terminal fusion proteins (namely COV, COI1::HA) (Devoto et al., 2002) and their genetic background Col gl1 (or Col5, Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre accession N1644) were used.

Transformation and maintenance of arabidopsis cell cultures

Arabidopsis ecotype Landsberg erecta (Ler) cell suspension cultures derived from undifferentiated calli were transformed with Agrobacterium tumefaciens adapting the method of Ferrando et al. (2000) and O’Brien et al. (2012), with the construct containing the intron-tagged COI1 (Devoto et al., 2002). The suspension cultures were maintained in Murashige and Skoog basal salts with minimal organics (MSMO) medium (Sigma) containing sucrose (30 g L–1), naphthalene acetic acid (0.5 mg L–1) and kinetin (0.05 mg L–1), and buffered to pH 5.6–5.7 with sodium hydroxide. The cultures were kept under low light intensity (80 μmol m–2 s–1) in a continuous light regime.

Treatment of seedlings and cell cultures with methyl jasmonate

Arabidopsis seedlings (9, 13 and 19 d after stratification) were grown and treated according to Noir et al. (2013). The kinematic analysis of the first true leaves of Col gl1 and COV was performed according to Noir et al. (2013).

Arabidopsis Ler cell cultures were treated with medium containing 50 μM MeJA or the equivalent volume of ethanol (final concentration 0.05 %) 24 h after being transferred to new medium for the treatment duration indicated.

Molecular biology techniques

Purification of total RNA from plant material was performed using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen).

Quantitative real-time amplification (qRT-PCR) in the presence of SYBR Green was performed using the SYBR®GREEN jumpstart taq readymix (Sigma) adapting the protocol from Noir et al. (2013). AT5G55480 was used as a reference gene as per Noir et al. (2013), and the ΔΔCt (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008) method was applied for the calculations. Primers (Supplementary Data Table SI) were designed using QuantPrime (http://quantprime.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/) (Arvidsson et al., 2008).

SDS–PAGE was carried out according to Laemmli (1970) in a BioRad unit. Protein staining was performed using 0.25 % Coomassie brilliant blue (Imperial Protein staining solution, Sigma). Total protein extractions were performed according to Devoto et al. (2002), and protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Protein Assay, Bio-Rad). For western blotting, 10–15 μg of total protein was loaded and analysis was performed according to Devoto et al. (2002). The following antibodies were used: peroxidase-coupled monoclonal anti-HA antibody 3F10 (1:1000; Roche) and COI1 antiserum (1:1000; Agrisera).

Ploidy measurement

Ploidy levels were measured using the Cystain UV Precise P high-resolution DNA staining kit (Partec) adapting a procedure from Dolezel et al. (2007) and Noir et al. (2013). Flow cytometry experiments were repeated at least three times for each genotype using independent biological replicates.

Arabidopsis protoplasts isolation and imaging

For cell wall digestion 3 mL of PCV (packed cell volume) was used for 0, 2, 4 and 6 days after sub-culturing (DASU). Protoplasts were isolated as previously described (Mathur et al., 1995) and counted using a haemocytometer (Fuchs-Rosenthal). The protoplasts were imaged using a Nikon NiE Upright microscope, and cell number and cell volume were analysed with ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Proteolytic digestion and identification of peptides by nano-liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry

Extraction of apoplastic washing fluid (AWF) and in-gel trypsin digestion of polypeptides for mass spectrometry was performed according to O’Brien et al. (2012). Mass spectrometry was performed on a hybrid linear ion-trap orbitrap instrument (Orbitrap XL, Thermo Scientific) using a high-resolution precursor measurement (filtered at <10 ppm) and low-resolution product ion spectra on the ion-trap. Peptide identifications were made using Mascot software (Matrix Sciences).

Analysis of polar metabolites by GC-MS

Four independent biological replicates for wild type and COV samples either untreated, mock treated (ethanol vehicle) or 50 μm MeJA treated (24 samples in total) were analysed. Samples for metabolite analysis by GC-MS were prepared according to Gullberg et al. (2004). Metabolomic analysis was performed on a Hewlett Packard 5890 Series II gas chromatograph equipped with a Hewlett Packard 7673 Autosampler and a 25 × 0.22 mm id DB5 column with 0.25 μm film, interfaced to a Hewlett Packard 5970 mass sensitive detector (Agilent Technologies, Stockport, UK). GC-MS analysis was carried out according to O’Brien et al. (2012). The data were analysed with Chemstation software (Agilent) and mass spectra were extracted using AMDIS 32 v.2.72 (Automated Mass Spectral Deconvolution and Identification System, http://amdis.net/index.html) and submitted to the NIST 2014 (National Institute of Science and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA; http://www.nist.gov/index.html) and Golm Metabolome Database (GMD) (Hummel et al., 2010) mass spectra libraries. Only the features confirmed with both databases were selected.

Data analysis

Individual chromatogram peak areas above threshold (peak area >7000 TIC units) expressed as ratios to the total peak areas were processed. Relative metabolite abundances were tested for statistical significance using R (R Development Core Team, 2011). The multiple comparison method was a Tukey HSD test, following a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; the response variable was metabolite abundance and the model was treatment × cells). For all experiments described, at least three independent biological replicates were tested, unless otherwise stated. The s.e. is shown as ± of the mean. All graphs, tables and volcano plots were produced using Microsoft Office Excel 2010.

RESULTS

MeJA and COI1 overexpression repress cell proliferation in stably transformed arabidopsis cell cultures

To generate COI1-overexpressing plant cells, Ler arabidopsis cell cultures (representing the wild type and referred to here as Ler) were transformed with the 35S::COI1::HiA construct as described before (Devoto et al., 2002). Two separate microcolonies were selected to generate independent stable cell suspensions (referred to here as COV, COI-overexpressing, COV1 and COV2). Ectopic expression of the COI1::HA protein was confirmed in both COV1 and COV2 cell cultures by immunodetection using an HA-specific antibody. Higher levels of COI::HA were detected in COV2 in comparison with COV1 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Detection of COI1::HA in Ler and COI1-overexpressing cell suspension cultures. Total protein was extracted from the wild type (Ler) and the COI1-overexpressing cell suspensions (COV1 and COV2) at 4 DASU, and run on a 12 % SDS–polyacrylamide gel. COI1 and COI::HA mass was approx. 67–68 kDa. A 10 μg aliquot of protein extract were loaded for Ler and COV1, and 2 μg for COV2.

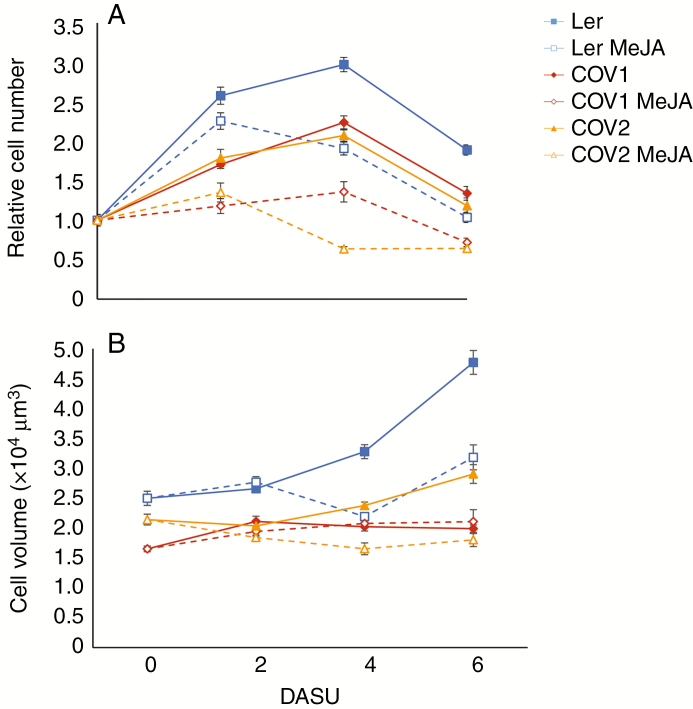

It was shown previously that MeJA affects the cell cycle via COI1 in arabidopsis plants (Noir et al., 2013). To study the effect of COI1 overexpression on cell proliferation in the absence of organ developmental control, the increase in relative cell numbers over time in Ler, COV1 and COV2 cell suspensions was compared. All three cultures exhibited higher relative cell numbers on subsequent days, with a maximum at 4 DASU (Fig. 2A). While relative cell number in Ler culture showed an approx. 3-fold increase at 4 DASU, the increase in COV1 and COV2 cultures reached about 2-fold. Following MeJA treatment (50 μm) at 1 DASU, the cell numbers decreased. At 4 DASU, the relative cell number of the Ler culture was reduced by about 36 %, whereas the JA receptor-overexpressing COV1 and COV2 cultures showed an approx. 39 % and approx. 69 % decrease, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cell number (A) and volume (B) of Ler and COV cell suspensions. Cells were treated with 50 μm MeJA at 1 DASU. MeJA-treated and untreated cell suspensions were collected at 2 d intervals and subjected to enzymatic digestion to release protoplasts, from which the cell number (cell mL–1) and cell volume (μm3) was determined using the Image J software (Schneider et al., 2012). (A and B) Data represent the average of five independent biological replicates ± s.e. per line with n = 417–3145.

MeJA and COI1 overexpression arrest the cell cycle in G2/M transition

To investigate further the effects of COI1 overexpression and MeJA elicitation on cell cycle progression, the DNA content of the cultured cells was measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A, B; Supplementary Data Table SII and Fig. S1). At 4 DASU, and measuring cell division parameters (Fig. 3C, D), most of the Ler cells were in G1 phase (approx. 76 %), and a very similar distribution was observed in COV1, with approx. 74 % of the cells in G1. In contrast, in COV2, a decreased frequency of G1 phase cells was detected (approx. 40%), with most of the cells being in G2/M. After MeJA treatment of Ler, a shift towards G2/M phase was observed in the population, and this shift could be further enhanced by increasing the MeJA concentration to 200 μm. This suggests that MeJA triggered either a G2 arrest or exit from the cell cycle. The fact that in the wild type, following ploidy analysis, MeJA was observed to lead to the appearance of 8C nuclei suggests that the latter had occurred in this case (Fig. 3A). In COV1 cultures, the addition of 50 μm MeJA already resulted in a higher proportion of G2/M cells (approx. 45 %), and this could be enhanced by 200 μm MeJA (Fig. 3C), and a similar trend was observed at 6 DASU. In contrast, upon MeJA treatment, the cell cycle phase distribution was unaffected in COV2 cells at both 4 and 6 DASU. These results extend previous findings that in arabidopsis cell suspensions MeJA has a negative effect on cell proliferation by arresting cells in the G2 phase (Pauwels et al., 2008). Significantly here, the overexpression of COI1 enhanced the MeJA sensitivity of cells towards a G2 cell cycle arrest, although in COV2 cell cultures the higher COI1 expression may result in an even earlier G2 arrest, therefore masking the effect of MeJA.

Fig. 3.

MeJA alters cell cycle progression in Ler and COV cell suspensions. Quantitative analysis of nuclear DNA content in Ler and COV cell suspensions performed by flow cytometry analysis of cell suspensions at 4 and 6 DASU treated with 50 μm (+) and 200 μm (++) MeJA at 1 DASU. (A and B) Average frequencies of the observed ploidy levels of a minimum of three independent biological replicates ± s.e. (C and D) Cell cycle analysis of flow cytometry data at 4 (C) and 6 (D) DASU. The analyses were performed on at least 20 000 nuclei isolated for each ploidy measurement.

MeJA and COI1 overexpression differentially regulate key cell cycle marker genes

To gain insights into the role of COI1 overexpression in cell cycle regulation, the transcription of selected cell cycle marker genes was monitored by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4A–G). The efficacy of the MeJA treatment was assessed by analysing the expression of the ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE gene (AOS; AT5G42650) (Fig. 4M).

Fig. 4.

qRT-PCR analysis of cell cycle (A–G) and cell wall (H–L) remodelling markers over time. Transcript levels in Ler and COV cell suspensions by extracting RNA from 0, 2, 4 and 6 DASU cell suspensions. AT5G55480 was used as a reference gene as per Noir et al. (2013), and the ΔΔCt (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008) method was applied for the calculations. MeJA (50 μm) was applied to Ler, COV1 and COV2 cell suspensions at 1 DASU. The allene oxide synthase (AOS) gene was analysed to test the effectiveness of the MeJA treatment (M). Data are the averages ± s.e. of three independent biological replicates, and reactions were performed in triplicate. Results are expressed as log2 fold changes normalized to the 0 h time point for each genotype.

In Ler, transcription of cell cycle markers was induced for 2–4 DASU, reflecting the high mitotic activity of cells in the nutrient-rich media. As the nutrients were consumed, the activity of cell cycle markers started to decrease. Transcription of CYCLIN B1;1 (CYCB1;1; AT4G37490), a checkpoint regulator at the G2/M transition (Dewitte et al., 2003), was elevated upon sub-culturing and was the highest at 2 DASU. Throughout the culturing period, higher CYCB1;1 levels in COV cultures were measured. MeJA treatment lowered CYCB1;1 expression, and the rate of reduction was higher in COV1 and 2 at 4 DASU. Transcription of the G2/M-specific cyclin-dependent kinase genes CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE B2;1 (CDKB2;1; AT1G76540) and CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE B2;2 (CDKB2;2; AT1G20930), key regulators of cell cycle progression, was also elevated, being the highest at 4 DASU in Ler followed by COV1 and COV2. MeJA treatment decreased the expression of both CDKB2;1 and CDKB2;2. CYCD1;1 (CYCLIN D1;1; AT1G70210) differentially increased but peaked very similarly at 4 DASU in all three cultures. When MeJA was applied to the cell cultures, the CYCD1;1 levels were reduced, particularly so for COV2 at 4 DASU. A known function of CYCD3 gene products is to delay the onset of endoreduplication (Dewitte et al., 2007). Expression of CYCD3;1 (CYCLIN D3;1; AT4G34160) was reduced in COV2, while CYCD3;3 (CYCLIN D3;3; AT3G50070) was downregulated in both COV cell cultures when compared with Ler. MeJA treatment further decreased CYCD3;1 but not CYCD3;3 transcript levels. In arabidopsis plants, the expression of genes required for the onset of the synthesis (S) phase, such as CELL DIVISION CONTROL 6 (CDC6/CDC6A; AT2G29680), was shown to be downregulated by MeJA, consistently with the reduction of cell proliferation and the repression of endoreduplication (Noir et al., 2013). In Ler cultures, the reduction in expression of this S-phase marker is associated with the overexpression of COI1 but not with MeJA treatment. Similarly, the expression levels of CDKB2;1, CDKB2;2, and CYCD1;1 are lower in COV cultures.

To summarize, gene expression analysis demonstrated that MeJA has a negative effect on the transcription of cell cycle genes and indicated that the effects of COI1 overexpression did not always correlate with the MeJA treatments; this could suggest a MeJA-independent COI1 function specifically related to organ developmental control.

MeJA and COI1 overexpression reduce protoplast volume and alter the expression of genes encoding cell wall-modifying enzymes

The size of cultured cells is affected by a decrease of osmolality of the media caused by nutrient depletion (Felix et al., 2000). Changes in the average protoplast volume of all three cultures over time were observed (Fig. 2B). At 6 DASU, Ler cells reached a 2-fold increase in protoplast volume compared with day 0, but COI1 overexpression prevented normal cell enlargement in both COV1 and COV2. Treatment with MeJA led to reduced cell volume in Ler cultures and resulted in only an approx. 1.3-fold increase at 6 DASU. Moreover, MeJA had no effect on COV1 cell sizes, and notably COV2 cells were more sensitive to the treatment.

MeJA negatively affects cell cycle progression during leaf development in arabidopsis (Noir et al., 2013). The leaf area of in vitro grown Col gl1 and of lines overexpressing COI1 (Devoto et al., 2002) was measured here. The first true leaves of COV plants were analysed according to Noir et al. (2013) (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Kinematic analysis confirmed that leaf growth was inhibited by MeJA treatment on average by about 80 % for both lines. Average cell area was also consistently reduced by the treatment, as was cell number, as previously demonstrated (Noir et al., 2013). Here the average leaf area of untreated COV leaves is smaller than that of Col gl1 especially during the earlier stages of leaf development (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). These observations not only are in agreement with the data obtained in cell culture but also complement our previous data showing larger leaf size for the coi1-16B mutant (Noir et al., 2013). At the same time, increased levels of the JA receptor in planta do not necessarily enhance the response to the phytohormone.

As changes in cell volume also depend on cell wall elasticity (Zonia and Munnik, 2007), the expression of genes involved in cell wall remodelling was studied (Fig. 4H–L). Cellulose synthase-like A (CSLA) proteins regulate the synthesis of mannan polysaccharides, structural constituents of the cell wall (Goubet et al., 2009). It was previously shown that one of the CSLA family genes, CELLULOSE SYNTHASE LIKE A10 (CSLA10; AT1G24070), is induced by MeJA in arabidopsis (Noir et al., 2013). In Ler, CSLA10 transcription increased after sub-culturing, peaked at 2 DASU, then gradually decreased. In COV2, the CSLA10 expression pattern was similar to that of Ler. MeJA treatment increased the transcription of CSLA10, particularly in COV2 cultures. The POLYGALACTURONASE-INHIBITING PROTEIN 2 (PGIP2; AT5G06870) gene inhibits cell wall loosening to hinder the activity of pathogen polygalacturonases, thereby preventing cell expansion (O’Brien et al., 2012). Here, PGIP2 expression had a similar pattern in all cultures, with an initial decrease at 2 DASU followed by a linear increase. COI1 overexpression lowered PGIP2; however, MeJA elicitation triggered its transcription in all cultures, reaching a maximum at 2 DASU with generally higher levels in COV cultures. The inducibility of the PGIP2 transcripts by MeJA is also consistent with previous in planta data (Ferrari et al., 2003).

Cell wall pectins are highly methyl esterified, and their de-esterification by pectin methylesterases (PMEs) increases cell wall rigidity (Parre and Geitmann, 2005), which plays a crucial role in defence against pathogens. Moreover, pathogen-induced PME activity depends on JA signalling (Bethke et al., 2014). PMEs are counteracted by methylesterase inhibitors (PMEIs) (De Caroli et al., 2011); this action contributes to cell wall remodelling during growth (Lionetti et al., 2012). The expression of the characterized PECTIN METHYLESTERASE INHIBITOR 3 (PMEI3; AT5G20740), PECTIN METHYLESTERASE 3 (PME3; AT3G14310) and METHYLESTERASE PCR A (ATPMEPCRA; AT1G11580) was tested. MeJA induced the transcription of ATPMEPCRA, also in agreement with data reported in Genevestigator (Hruz et al., 2008). However, the expression of this gene, and of PME3, was downregulated by COI1 overexpression.

COI1 overexpression induces changes in cell wall protein abundance

As the alteration of cell growth may be linked to cell wall-related changes, the apoplastic proteome of cell cultures overexpressing COI1 was analysed. In previous studies using the same arabidopsis Ler cell suspension culture, cytosolic contamination was deemed negligible as it was below the detection limit in CaCl2 extracts (Chivasa et al., 2002; O’Brien et al., 2012). The CaCl2-extracted cell wall proteins were analysed in COV1 (with protein expression levels of the COI1::HA fusion more similar to the native endogenous levels; Fig. 1) and the more abundant proteins compared with Ler were selected (Fig. 5, bands 4, 5 and 6 in COV1). No obvious protein abundance changes were detected in CaCl2-extracted cell wall proteins in MeJA-treated samples compared with untreated samples, in both Ler and COV1 samples (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). However, differences were identified between Ler and COV1 samples as shown in Fig. 5 (bands 1 and 4, 2 and 5, 3 and 6; Table 1). The proteins were identified as OLIGOGALACTURONIDE OXIDASE 1 (OGOX1; Benedetti et al., 2018; AT4G20830; bands 1 and 4), BETA-GLUCOSIDASE (AT3G18080; bands 1 and 4)/ENDOGLUCANASES (AT1G71380/AT1G70710; bands 2 and 5) and PGIP2 (bands 3 and 6) (Supplementary Data Table SIII). The defence-related protein PGIP2 (Devoto et al., 1998; Ferrari et al., 2006) was visibly more abundant in COV1 compared with Ler.

Fig. 5.

SDS–PAGE analysis of apoplastic proteins in Ler and COV cell suspensions. Ler and COV cell cultures grown for 7 d were gently vacuum filtered and then incubated for 30 min in 200 mm CaCl2 as described in the Materials and Methods. Proteins were precipitated with chloroform/methanol, resuspended in sample buffer and separated by SDS–PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue R250 for protein visualization. Arrows indicate bands selected for in-gel trypsin digestion and sequencing. Protein IDs are listed in Table 1 and peptides are listed in Supplementary data Table SIII. A representative SDS–polyacrylamide gel is shown of three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Proteins identified by in-gel trypsin digestion of CaCl2-extracted cell wall proteins of arabidopsis Ler wild type (WT) and Ler COV

| Band no. | AGI number | Description | Score | Pep.# | Cover % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ler WT//Ler COV | |||||

| 1/4 | AT4G20830 | Oligogalacturonide oxidase 1 | 1254//43 | 24//4 | 48//9 |

| 1/4 | AT3G18080 | Beta-glucosidase | 1361//3495 | 72//57 | 55//57 |

| 2*/5* | AT1G71380/AT1G70710 | Endoglucanases | 5236/2345//4026/1525 | 10//6 | 33//17 |

| 3/6 | AT5G06870 | Polygalacturonase Inhibiting protein 2 (PGIP2) | 3460//2904 | 12//11 | 38//39 |

Pep.#, number of peptides; Cover %, protein coverage expressed as a percentage; Score, threshold set at P < 0.05.

*Only the proteins with the highest scores are shown. The Score value was taken from MASCOT and represents the probability that the protein identified is not random and is based on the peptides identified.

COI1 overexpression induces changes in whole-cell metabolites

Available studies on metabolic profiling of arabidopsis cell cultures in response to JAs are extremely diverse and do not yield a coherent picture. In this study, whole-cell extracts of Ler and COV1 cell cultures at 2 DASU were profiled by GC-MS as O-methyloxime-trimethylsilyl derivatives for the analysis of amino acids, monosaccharides, fatty acids and organic acids. GC-MS chromatograms showed approx. 68 peaks, representing putative metabolites (Supplementary Data Table SIV). The relative abundances of each peak were processed as a ratio of the total peak area and tested for statistical significance. The metabolites that were differentially regulated across all biological replicates were selected. A pair-wise comparison was carried out between untreated Ler and COV cells. Both lines were treated with 50 μm MeJA for 24 h and pair-wise comparisons between mock-treated and MeJA-treated cells were performed within Ler and COV.

Twelve significant metabolite changes were identified in COV when compared with Ler and are therefore associated with the overexpression of COI1 (Fig. 6). Metabolites accumulating in COV1 with significant P-values (P < 0.05) and fold change values >2 (except for glucose) are shown (Fig. 6A). Relative mean abundances of β-alanine, erythrono-1,4-lactone, erythronic acid, threonic acid, putrescine, glucose, gluconic acid, myo-inositol, sedoheptulose and two unknown metabolites are plotted (Fig. 6B), identifying glucose as the most abundant among the differentially regulated metabolites and 1.9-fold upregulated in COV1 (P < 0.026). Most metabolites appear to accumulate at higher levels in COV1 relative to Ler, indicating a change in primary metabolism associated with the overexpression of the COI1 receptor, but only the above-mentioned 12 metabolites pass the significance threshold (Fig. 6A). Four significant metabolite changes were identified within Ler or COV1 cell culture following MeJA treatment (Supplementary Data Fig. S4). Succinic acid was the only significantly changed metabolite found in Ler; it was 2.2-fold upregulated (P < 0.001) following MeJA treatment (Table 2). Succinic acid was also significantly upregulated (P < 0.004) in MeJA-treated COV1 samples (Table 2) together with the amino acids alanine (P < 0.013) and serine (P < 0.036) that were also shown to be significantly upregulated in COV1 upon MeJA treatment (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Differentially regulated metabolites in arabidopsis cell culture associated with the overexpression of the JA receptor COI1. Significant metabolite changes in COV1 cell culture compared with Ler (both untreated) using GC-MS. (A) Volcano plot of metabolomics data. The x-axis is the mean ratio fold change (plotted on a log2 scale) of the relative abundance of each metabolite between untreated Ler and COV1. The y-axis represents the statistical significance P-value (plotted on a –log10 scale) of the ratio of relative abundances for each metabolite. Metabolites highlighted in red (and also represented in B) hyperaccumulate in COV1 cell culture and have significant P-values (orange threshold bar represents P < 0.05) and high fold change values (>2). (B) The vertical scale bars (log10) represent the relative metabolite abundance normalized to the total peak areas. Metabolites shown are significantly different (P < 0.05) according to pair-wise comparison using Tukey HSD test. Data represent the means of four independent biological replicates and error bars represent the s.e.

Table 2.

Differentially regulated metabolites in 2-day-old Ler and COV1 cell cultures following 50 µm MeJA treatments for 24 h analysed using GC-MS.

| Metabolite | Ler | COV1 | COV1/Ler | Ler | COV1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN | UN | Fold | P | Mock | MeJA | Fold | P | Mock | MeJA | Fold | P | |

| Unknown | 0.4 ± 0.08 | 1.64 ± 0.526 | 4.07 | 0.016* | 0.56 ± 0.107 | 0.37 ± 0.028 | 0.67 | 0.993 | 0.81 ± 0.179 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.995 |

| β-Alanine | 0.18 ± 0.069 | 1.97 ± 0.773 | 10.89 | 0.017* | 0.32 ± 0.041 | 0.25 ± 0.013 | 0.81 | 0.999 | 0.66 ± 0.203 | 0.95 ± 0.24 | 1.44 | 0.990 |

| Erythrono-1,4-lactone | 0.42 ± 0.032 | 2.81 ± 0.835 | 6.67 | 0.005* | 0.71 ± 0.252 | 1.06 ± 0.144 | 1.50 | 0.986 | 1.39 ± 0.15 | 1.55 ± 0.322 | 1.12 | 0.999 |

| Erythronic acid | 8.11 ± 1.022 | 26.02 ± 7.902 | 3.21 | 0.017* | 10.04 ± 1.305 | 8.28 ± 0.385 | 0.83 | 0.999 | 14.23 ± 1.03 | 14.39 ± 1.957 | 1.01 | 0.999 |

| Threonic acid | 0.27 ± 0.096 | 2.31 ± 0.844 | 8.66 | 0.048* | 1.69 ± 0.566 | 1.62 ± 0.126 | 0.96 | 0.999 | 1.03 ± 0.122 | 1.18 ± 0.399 | 1.14 | 0.999 |

| Putrescine | 1.34 ± 0.131 | 3.93 ± 1.156 | 2.94 | 0.034* | 1.79 ± 0.374 | 1.47 ± 0.356 | 0.82 | 0.998 | 2.34 ± 0.294 | 2.4 ± 0.277 | 1.02 | 0.999 |

| Unknown | 1.44 ± 0.083 | 3.23 ± 0.689 | 2.24 | 0.011* | 1.6 ± 0.188 | 1.44 ± 0.071 | 0.90 | 0.999 | 2.17 ± 0.059 | 1.94 ± 0.319 | 0.90 | 0.996 |

| Glucose | 119.38 ± 5.558 | 230.63 ± 52.398 | 1.93 | 0.023* | 114.84 ± 5.217 | 161.81 ± 7.307 | 1.41 | 0.664 | 154.07 ± 5.796 | 210.77 ± 4.559 | 1.37 | 0.478 |

| Gluconic acid | 1.04 ± 0.216 | 3.56 ± 0.897 | 3.44 | 0.022* | 1.16 ± 0.107 | 0.82 ± 0.186 | 0.70 | 0.996 | 1.85 ± 0.189 | 2.55 ± 0.742 | 1.38 | 0.914 |

| Myo-inositol | 36.74 ± 3.011 | 79.97 ± 20.922 | 2.18 | 0.026* | 36.82 ± 2.204 | 35.47 ± 1.312 | 0.96 | 0.999 | 46.52 ± 1.355 | 31.18 ± 1.944 | 0.67 | 0.812 |

| Sedoheptulose | 0.08 ± 0.077 | 2.39 ± 0.879 | 30.84 | 0.006* | 0 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | N/A | 0.999 | 1.18 ± 0.24 | 1.51 ± 0.259 | 1.28 | 0.990 |

| Unknown | 2.28 ± 0.517 | 9.53 ± 2.845 | 4.19 | 0.013* | 2.69 ± 0.493 | 2.19 ± 0.262 | 0.81 | 0.999 | 5.63 ± 0.467 | 5.36 ± 1.365 | 0.95 | 0.999 |

| Succinic acid | 2.29 ± 0.086 | 2.09 ± 0.541 | 0.91 | 0.998 | 2.81 ± 0.079 | 6.15 ± 0.243 | 2.19 | 0.000† | 1.04 ± 0.075 | 3.1 ± 0.54 | 2.99 | 0.004† |

| Alanine | 1.33 ± 0.145 | 2.48 ± 0.841 | 1.86 | 0.439 | 2.76 ± 0.164 | 3.74 ± 0.125 | 1.35 | 0.602 | 1.41 ± 0.142 | 3.75 ± 0.562 | 2.66 | 0.013† |

| Serine | 1.21 ± 0.159 | 2.5 ± 0.935 | 2.06 | 0.419 | 2.5 ± 0.146 | 3.71 ± 0.075 | 1.49 | 0.476 | 1.61 ± 0.238 | 3.84 ± 0.594 | 2.39 | 0.036† |

Differences in relative mean abundances ± s.e and fold changes are presented.

*P < 0.05 of COV1 compared with Ler, both untreated (UN).

† P <0.05 comparing MeJA and mock treatment in Ler wild type or Ler COV samples.

DISCUSSION

A role for COI1 in regulating the cell cycle and cell wall remodelling

Stably transformed arabidopsis Ler cell cultures (COV) have proven to be a reliable system to study the growth dynamics of plant cells, and to analyse related gene and protein expression and changes in metabolism. Our results showed that MeJA treatment and COI1 overexpression negatively affected growth in cell cultures. A degree of synergy between the levels of COI1 overexpression and MeJA treatment on the repression of cell proliferation was observed (Figs 1 and 2).

Jasmonate-mediated metabolite production has been used for pharmaceutical and biotechnological purposes (Patil et al., 2014), and the accumulation of metabolites in response to MeJA elicitation reduces cell growth in Nicotiana tabacum BY-2 and Panax ginseng cell suspensions (Goossens et al., 2003; Thanh et al., 2005). The activation of defence responses redirects energy resources from primary metabolism at the expense of growth (Patil et al., 2014). Recently, the JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ)–MYC transcriptional module was highlighted as the molecular basis behind the regulation of growth–defence balance (Major et al., 2017b), pointing towards a complex signalling hub mediating cross-talk between hormone and light signalling pathways (Major et al., 2017a). Major et al. (2017a) proposed a model suggesting that growth and defence trade-offs are a consequence of a transcriptional network that evolved to maximize plant fitness, rather than just being the result of metabolic constraints. Taken together, our findings indicate that MeJA inhibits cell growth through the JA receptor COI1, in line with the notion that JAs contribute to regulating the trade-off between defence mode and plant growth (Yang et al., 2012; Noir et al., 2013).

Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry at 4 DASU, which coincides with the highest cell number in the untreated cultures, showed that MeJA promotes a shift from G1 to G2/M in Ler cells in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting a G2 arrest that leads to reduced or delayed cell division (Figs 1 and 3). COI1 overexpression mimics the effect of MeJA treatment which further enhanced the shift from G1 to G2/M in COV1 lines but not in COV2. MeJA was shown to block both G1 and G2/M transitions in tobacco BY2 cell cultures (Światek et al., 2002) and to mediate the arrest in G2 phase in arabidopsis cell cultures (Pauwels et al., 2008). In asynchronously dividing Taxus cell cultures, MeJA affected cell cycle progression by transiently increasing cells in G2 phase (Patil et al., 2014). A role for MeJA in the regulation of cell cycle progression in arabidopsis plants was reported (Noir et al., 2013), demonstrating that MeJA inhibits mitosis, arresting the cell cycle in G1 prior to the transition to S phase, in a COI1-dependent manner.

It is shown here that COI1 overexpression inhibits or delays progression of the cell cycle in cell suspensions, specifically blocking G2/M transition, suggesting a mechanistic difference and further clarifying the role of the JA receptor in the absence of organ developmental control.

Analysis of selected cell cycle marker genes suggested that MeJA also promotes a switch to endoreduplication in a COI1-dependent manner in planta (Noir et al., 2013). However, this process is not evident in cell cultures. The accumulation of CYCB1;1, CDKB2;1 and CDKB2;2 was reduced following MeJA treatment (Fig. 4). Consistently, COI1 overexpression reduced mRNA levels of CDKBs in COV cell cultures, which further supports a role for COI1 in mediating cell cycle progression. However, the expression of CYCB1;1 was upregulated in COV lines in comparison with Ler cultures. This observation, counterintuitive at face value, is nevertheless in line with a previous report showing G2 arrest of arabidopsis root cells and CYCB1;1 accumulation after γ-irradiation (Ricaud et al., 2007).

CYCD1;1 was shown to regulate the cell cycle positively through its function at G0/G1/S and in S/G2 transitions and to accelerate cell proliferation in BY-2 cells upon overexpression (Koroleva et al., 2004). Here, transcripts of CYCD1;1 were reduced upon MeJA treatment in all cell cultures, indicating that this D-type cyclin could mediate the inhibition of cell proliferation following MeJA signalling, in agreement with in planta data from Noir et al. (2013). The levels of CYCD3;1 transcripts were reduced in COV2 and by MeJA treatment. CYCD3;3 activity was repressed in both COV cell lines, consistent with the findings of Oakenfull et al. (2002). CYCD3s negatively regulate endoreduplication by extending the competency to enter mitosis (Dewitte et al., 2007). The shift from G1/S to G2/M phases identified by flow cytometry could therefore be mediated by CYCD3 in a context where the endocycle is not started. The repression of CDC6 expression in COV cultures suggests that COI1 may act on this key limiting factor to stall the S phase prior to replication and, consequently, to the G2 phase. The arrest of cell cycle in G2/M transition observed in COV (Fig. 3) could also depend on reduced COI1-dependent CDKB2 activity (Zhiponova et al., 2006)

MeJA treatment and COI1 overexpression reduced the cell volume (Fig. 1B). The composition of the cell wall plays a key role in maintaining the equilibrium between osmotic pressure and cell expansion (Parre and Geitmann, 2005; Sarkar et al., 2009; Pauly and Keegstra, 2016). It can be hypothesized that the MeJA/COI1 pathway affected cell wall structure, leading to an increased cell wall rigidity hindering cell enlargement. MeJA was shown to induce the expression of the lignin precursor monolignol biosynthetic genes in arabidopsis cell cultures (Pauwels et al., 2008). Moreover, JAs regulate cell wall composition as part of JA-mediated defence responses in potato, by targeting the activity of PMEs (Taurino et al., 2014).

To better understand how the MeJA/COI1 pathway regulates cell wall remodelling, the expression of genes associated with this process and JA signalling was analysed (Fig. 4). Notably, the expression of CSLA10 was induced by COI1 overexpression in combination with MeJA treatment, ascribing a role for COI1 in regulating production of hemicelluloses. The data are also in line with the role of JAs in regulating cellulose biosynthesis (Ellis and Turner, 2001).

During necrotrophic infection, cell wall integrity is protected by inhibitors of pathogenic cell wall-degrading enzymes (Bellincampi et al., 2014). PGIP2 contributes to cell wall rigidity independently of biotic stress (O’Brien et al., 2012). The expression of PGIP2 was shown to be upregulated by MeJA, and it was undetectable in coi1 and jar1 mutants after Botrytis cinerea infection (Ferrari et al., 2003). Consistently, our results showed that MeJA induced PGIP2 transcription, and this could be further enhanced when COI1 was overexpressed.

The PMEs and their inhibitory PMEIs are also involved in cell wall remodelling (Lionetti et al., 2012). PMEs remove methyl esters from the pectin polymers, and the free pectins cross-link with Ca2+, increasing cell wall firmness (Willats et al., 2001). The activity of plant PMEs is inhibited by PMEIs during plant growth and during pathogen defence (Parre and Geitmann, 2005; Lionetti et al., 2007). The induction of PME activity is dependent on JA signalling in arabidopsis and potato (Bethke et al., 2014; Taurino et al., 2014). A link between JA and transcription of PMEIs was also established in arabidopsis, as exogenous MeJA and ethylene could activate the pepper CaPMEI1 promoter (An et al., 2009). Overexpression of arabidopsis PMEI1 and PMEI2 reduces PME activity, and increases the levels of pectin methyl esterification (Lionetti et al., 2007) along with root length. The overexpression of PMEI2 also increased plant growth and the vegetative biomass yield in arabidopsis, suggesting a role in enhancing cell expansion (Lionetti et al., 2010).

The reduction in transcription of PMEI3, PME3 and ATPMEPCRA in COV cell cultures demonstrates that COI1 regulates pectin de-esterification/methyl esterification through the selective modulation of these enzymes. The induction of ATPMEPCRA by MeJA suggests that the MeJA/COI1 pathways may control cell volume by increasing de-esterification and, as a result, rigidity.

Overall, a set of genes has been identified that function as targets of the MeJA/COI1-dependent pathway and whose function in cell wall remodelling could justify the inhibition of cell enlargement observed in Ler and COV cells.

Differentially regulated apoplastic proteins with a role in growth and defence

Four proteins were more abundant in the cell wall fraction of untreated COV1 cell suspensions (Fig. 5; Table 1; Supplementary Data Table SIII). These proteins have previously been identified in the cell wall (Bayer et al., 2006; O’Brien et al., 2012) and COI1 dependency was demonstrated in independent studies. Oligogalacturonide oxidase 1 (OGOX1) was recently characterized and specifically oxidizes oligogalacturonides. Plants overexpressing OGOX1 were also shown to improve resistance to Botrytis cinerea (Benedetti et al., 2018). A putative BERBERINE BRIDGE ENZYME gene (AT2G34810) was previously found to be induced by MeJA treatment or wounding and to be COI1 dependent (Devoto et al., 2005). Consistently, the phytotoxin coronatine induced accumulation of the elicitor-responsive transcript for the berberine bridge enzyme of Eschscholtzia californica (Weiler et al., 1994). Several glucanases also possess antimicrobial properties (Xu et al., 1994; Glazebrook et al., 2003). In arabidopsis, the BETA-1,3-GLUCANASE 2 (AT3G57260) transcripts were shown to be induced by wounding and MeJA (Devoto et al., 2005). Among the endoglucanases identified was Endoglucanase 9. This protein is a member of the glycosyl hydrolase family 9 (GH9) (also named endo-1,4-β-glucanase 9 or cellulase 3; AtCEL3; Urbanowicz et al., 2007). In rice, the gene encoding an ENDO-(1,3;1,4)-β-GLUCANASE has been described to respond to wounding and MeJA, whereby it was speculated that this response induces cell wall loosening during cell elongation and expansion as a step to regenerate injured cell walls in wounded leaf tissues (Akiyama et al., 2009). JAs play a role during cell wall synthesis (Koda, 1997; Cano-Delgado et al., 2000; Ellis and Turner, 2001, 2002); however, the association between JAs and cell expansion is so far limited (Brioudes et al., 2009). Noir et al. (2013) investigated the expression of genes with a role in cell expansion, revealing a complex picture made up of genes differentially regulated and COI1 dependent during development. The interaction of AtCEL3 with cyclins in arabidopsis cell suspensions (Van Leene et al., 2010) shed light on the mechanism of JA-dependent cell wall loosening to regulate cell growth. PGIPs have been shown to play a vital role in defence as extracellular inhibitors of fungal endopolygalacturonases (PGs) (Devoto et al., 1997, 1998; De Lorenzo et al., 2001; De Lorenzo and Ferrari, 2002; Ndimba et al., 2003; D’Ovidio et al., 2004). In this study, the PGIP2 protein levels were more abundant in COV cell wall fractions, while PGIP2 transcripts are induced by MeJA as previously shown (Ferrari et al., 2003) (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). It is conceivable to attribute such differences to differential stability in actively dividing cells of PGIP2 transcripts and protein levels, resulting in undetectable differences in total protein extracts following MeJA treatment.

COI1 overexpression and MeJA treatment affect primary metabolism

The comparison of metabolic fingerprints by GC-MS in previous studies of arabidopsis leaves with those of cultured arabidopsis cells (T87 line) (Axelos et al., 1992) showed similarities in the primary metabolite profiles and revealed moderate quantitative differences (Fukusaki et al., 2006). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy revealed that MeJA treatment of Arabidopsis plants increases flavonoids, fumaric acid, sinapoyl malate, sinigrin, tryptophan, valine, threonine and alanine, and decreases malic acid, feruloyl malate, glutamine and carbohydrates (Hendrawati et al., 2006). A study in tobacco showed that starch metabolic genes are differentially regulated in plant tissues by NtCOI1, highlighting the role of the JA signalling pathway in co-ordinating plant primary metabolism (Wang et al., 2014).

In this study, changes in the primary metabolism of arabidopsis Ler cell suspensions overexpressing the JA receptor COI1, as well as metabolite changes upon exposure to MeJA, were identified (Table 2). COI1 overexpression causes the accumulation of threonic acid, a product of ascorbic acid catabolism (Debolt et al., 2007). Endogenous JAs may regulate steady-state ascorbic acid levels (Suza et al., 2010). It is plausible that this turnover is accelerated in the transgenic cell suspension line. The increased abundance of β-alanine in COV1 cells may not be dependent on JAs in such a system, whilst MeJA increases its levels in plants (Broeckling et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2013).

Methyl jasmonate-triggered increases of the key amino acids alanine and serine were previously detected in N. tabacum (Hanik et al., 2010) and M. truncatula (Broeckling et al., 2005), providing substrates for the induction of downstream secondary metabolism for the plant defence response. In this study, levels of both amino acids were significantly increased in COV1 cells upon MeJA elicitation and appear to be more abundant in MeJA-treated Ler cells, however not significantly so.

Treatment of Ler and COV1 cells with MeJA induces succinic acid, a component of the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle). This was previously observed in Agastache rugosa (Kim et al., 2013) and in M. truncatula (Broeckling et al., 2005). Such induction may be indicative of reduced turnover, while metabolic activity is rescheduled from growth to stress responses. Similarly, succinate and citric acid levels decreased in lipoxygenase (LOX)-silenced tomato fruits (Kausch et al., 2012).

Glucose is an obligatory substrate of energy-producing glycolysis and polyhydroxy acids, and, together with erythronic acid, gluconic acid and threonic acid, was increased in COV1 cells. Interestingly, a study undertaken in arabidopsis showed that erythronic acid, gluconic acid and threonic acid levels increased in plants overexpressing GLYOXALASE2-1 (GLX2-1) under threonine stress (Devanathan et al., 2014). Whether the increase of such compounds in our study is a consequence of reduced turnover in COV1 cells rescheduling from growth to defence, and therefore directly linked with reduced growth rates in the COV1 cells, remains to be demonstrated.

Putrescine is the obligate precursor of spermidine and spermine, the major polyamines in plants. Polyamines regulate several cellular processes such as cell growth and stress tolerance (Capell et al., 2004; Kasukabe et al., 2004; Kusano et al., 2008). In this study, putrescine levels are significantly increased in COV1 cells. Increased putrescine levels have been proposed to play a role in response to abiotic stress and wounding (Bouchereau et al., 1999; Perez-Amador et al., 2002; Capell et al., 2004; Cuevas et al., 2008). The results are also in line with studies attributing a role to JAs and COI1 in regulating enzymes for the accumulation of putrescine (Perez-Amador et al., 2002; Goda et al., 2008).

Myo-inositol abundance was also increased in cells overexpressing COI1. Interestingly, InsP5 was described as a cofactor in the binding of JA-Ile to the receptor COI1, potentiating the strength of COI1–JAZ interactions (Sheard et al., 2010). While a direct connection is yet to be established, our data indicate an effect of COI1 on inositol metabolism.

Taken together with the finding that MeJA inhibits plant growth by repressing cell proliferation (Noir et al., 2013), this study contributes to the understanding of JA- and COI1-mediated growth control in the context of the production of metabolic resources and the trade-off with defence responses. This knowledge will positively impact our understanding of the complex single-cell relationships between micro-organisms and plants, and their regulation by hormonal and cell wall signalling. This work also provides tools to uncover novel mechanisms co-ordinating cell division and post-mitotic cell expansion in the absence of organ developmental control. An integrated picture of the results obtained is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

MeJA contributes to the regulation of the trade-off between defence mode and plant growth. Schematic representation of the cellular processes regulated by MeJA through the JA receptor COI1. MeJA inhibits cell proliferation via regulation of key components of the plant cell cycle and promotes changes in cell wall composition. Such modifications halt cell expansion while enhancing defence responses. MeJA induces metabolic reprogramming in plant cells to adjust to stress conditions, compromising growth. Shaded red and green shapes indicate accumulation or reduction in transcript, protein or metabolite levels, respectively.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Figure S1: flow cytometry of cell suspensions. Figure S2: COI1 overexpression in planta. Figure S3: SDS–PAGE analysis of cell wall proteins. Figure S4: differentially regulated metabolites in Ler and COV1. Table SI: primers used. Table SII: frequency of nuclei exhibiting 2C, 4C or 8C DNA content. Table SIII: list of peptides identified. Table SIV: list of metabolites identified.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We dedicate this work to the memory of Professor Paul Bolwell. Liu Ka, Fatima Aslam and Pauline Baker are acknowledged for technical help. Ler cell suspension cultures were a gift from Professor A. R. Slabas, Durham University, UK. De. A., O.J., B.M. I.P.S., W.J. and F.P. designed the research; De. A., O.J., B.M., I.P.S., J.K., P.S., T.-L.T. and F.P., performed the research; De. A., O.J., B.M., I.P.S., J.K., A.B. W.J., S.P. and F.P, analysed the data; De. A., O.J., B.M., I.P.S., J.K., Da. A. and F.P. wrote and edited the paper. The authors were supported by funding as follows: British Biotechnology Research Council (BBSRC; BB/E003486/1) to De. A.; The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and the Royal Society to De. A; O.J. is supported by the Chilean National Scholarship Program for Graduate Studies; B.M. is supported by SWAN (South West London Alliance Network grant to De. A.) and PrimerDesign (Student Sponsorship to B.M., Southampton, UK); I.P.S. is supported by WestFocus PARK SEED FUND INVESTMENT AWARD and H2020-MSCA-IF-2015 #705427; Da. A and F.P. are supported by BBSRC grant BB/E021166 (to B.G.P.). J.P.W. received support from NIH P30 DK063491. The data supporting the publication are included as supplementary materials.

LITERATURE CITED

- Akiyama T, Jin S, Yoshida M, Hoshino T, Opassiri R, Cairns JRK. 2009. Expression of an endo-(1,3;1,4)-β-glucanase in response to wounding, methyl jasmonate, abscisic acid and ethephon in rice seedlings. Journal of Plant Physiology 166: 1814–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An SH, Choi HW, Hong JK, Hwang BK. 2009. Regulation and function of the pepper pectin methylesterase inhibitor (CaPMEI1) gene promoter in defense and ethylene and methyl jasmonate signaling in plants. Planta 230: 1223–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson S, Kwasniewski M, Riano-Pachon DM, Mueller-Roeber B. 2008. QuantPrime – a flexible tool for reliable high-throughput primer design for quantitative PCR. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelos M, Curie C, Mazzolini L, Bardet C, Lescure B. 1992. A protocol for transient gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana protoplasts isolated from cell-suspension cultures. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 30: 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Balbi V, Devoto A. 2008. Jasmonate signalling network in Arabidopsis thaliana: crucial regulatory nodes and new physiological scenarios. New Phytologist 177: 301–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer EM, Bottrill AR, Walshaw J, et al. 2006. Arabidopsis cell wall proteome defined using multidimensional protein identification technology. Proteomics 6: 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellincampi D, Cervone F, Lionetti V. 2014. Plant cell wall dynamics and wall-related susceptibility in plant–pathogen interactions. Frontiers in Plant Science 5: 228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti M, Verrascina I, Pontiggia D, et al. 2018. Four Arabidopsis berberine bridge enzyme-like proteins are specific oxidases that inactivate the elicitor-active oligogalacturonides. The Plant Journal 94: 260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethke G, Grundman RE, Sreekanta S, Truman W, Katagiri F, Glazebrook J. 2014. Arabidopsis PECTIN METHYLESTERASEs contribute to immunity against Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Physiology 164: 1093–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP, Daudi A. 2009. Reactive oxygen species in plant–pathogen interactions. In: Rio LA, Puppo A, eds. Reactive oxygen species in plant signaling. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchereau A, Aziz A, Larher F, Martin-Tanguy J. 1999. Polyamines and environmental challenges: recent development. Plant Science 140: 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Brioudes F, Joly C, Szécsi J, et al. 2009. Jasmonate controls late development stages of petal growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 60: 1070–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeckling CD, Huhman DV, Farag MA, et al. 2005. Metabolic profiling of Medicago truncatula cell cultures reveals the effects of biotic and abiotic elicitors on metabolism. Journal of Experimental Botany 56: 323–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Delgado AI, Metzlaff K, Bevan MW. 2000. The eli1 mutation reveals a link between cell expansion and secondary cell wall formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 127: 3395–3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Delgado A, Penfield S, Smith C, Catley M, Bevan M. 2003. Reduced cellulose synthesis invokes lignification and defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 34: 351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell T, Bassie L, Christou P. 2004. Modulation of the polyamine biosynthetic pathway in transgenic rice confers tolerance to drought stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 101: 9909–9914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini A, Fonseca S, Fernández G, et al. 2007. The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature 448: 666–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivasa S, Ndimba BK, Simon WJ, et al. 2002. Proteomic analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana cell wall. Electrophoresis 23: 1754–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. 2005. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 6: 850–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas JC, Lopez-Cobollo R, Alcazar R, et al. 2008. Putrescine is involved in Arabidopsis freezing tolerance and cold acclimation by regulating abscisic acid levels in response to low temperature. Plant Physiology 148: 1094–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RB, Okada M, Ito Y, et al. 2001. Binding site for chitin oligosaccharides in the soybean plasma membrane. Plant Physiology 126: 1162–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debolt S, Melino V, Ford CM. 2007. Ascorbate as a biosynthetic precursor in plants. Annals of Botany 99: 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Caroli M, Lenucci MS, Di Sansebastiano GP, Dalessandro G, De Lorenzo G, Piro G. 2011. Dynamic protein trafficking to the cell wall. Plant Signaling and Behavior 6: 1012–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzo G, Ferrari S. 2002. Polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins in defense against phytopathogenic fungi. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 5: 295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzo G, D’Ovidio R, Cervone F. 2001. The role of polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins (PGIPs) in defense against pathogenic fungi. Annual Review of Phytopathology 39: 313–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denness L, McKenna JF, Segonzac C, et al. 2011. Cell wall damage-induced lignin biosynthesis is regulated by a reactive oxygen species- and jasmonic acid-dependent process in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 156: 1364–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanathan S, Erban A, Perez-Torres R, Kopka J, Makaroff CA. 2014. Arabidopsis thaliana glyoxalase 2-1 is required during abiotic stress but is not essential under normal plant growth. PLoS One 9: e95971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto A, Clark AJ, Nuss L, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. 1997. Developmental and pathogen-induced accumulation of transcripts of polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Planta 202: 284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Devoto A, Leckie F, Lupotto E, Cervone F, Lorenzo G De. 1998. The promoter of a gene encoding a polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein of Phaseolus vulgaris L. is activated by wounding but not by elicitors or pathogen infection. Planta 205: 165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto A, Nieto-Rostro M, Xie D, et al. 2002. COI1 links jasmonate signalling and fertility to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 32: 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto A, Ellis C, Magusin A, et al. 2005. Expression profiling reveals COI1 to be a key regulator of genes involved in wound- and methyl jasmonate-induced secondary metabolism, defence, and hormone interactions. Plant Molecular Biology 58: 497–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte W, Riou-Khamlichi C, Scofield S, et al. 2003. Altered cell cycle distribution, hyperplasia, and inhibited differentiation in Arabidopsis caused by the D-type cyclin CYCD3. The Plant Cell 15: 79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte W, Scofield S, Alcasabas AA, et al. 2007. Arabidopsis CYCD3 D-type cyclins link cell proliferation and endocycles and are rate-limiting for cytokinin responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 104: 14537–14542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezel J, Greilhuber J, Suda J. 2007. Estimation of nuclear DNA content in plants using flow cytometry. Nature Protocols 2: 2233–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ovidio R, Raiola A, Capodicasa C, et al. 2004. Characterization of the complex locus of bean encoding polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins reveals subfunctionalization for defense against fungi and insects. Plant Physiology 135: 2424–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C, Turner JG. 2001. The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 has constitutively active jasmonate and ethylene signal pathways and enhanced resistance to pathogens. The Plant Cell 13: 1025–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C, Turner JG. 2002. A conditionally fertile coi1 allele indicates cross-talk between plant hormone signalling pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana seeds and young seedlings. Planta 215: 549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix G, Regenass M, Boller T. 2000. Sensing of osmotic pressure changes in tomato cells. Plant Physiology 124: 1169–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando A, Farràs R, Jásik J, Schell J, Koncz C. 2000. Intron-tagged epitope: a tool for facile detection and purification of proteins expressed in Agrobacterium-transformed plant cells. The Plant Journal 22: 553–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Donatella V, Ausubel FM, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. 2003. Tandemly duplicated Arabidopsis genes that encode polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins are regulated coordinately by different signal transduction pathways in response to fungal infection. The Plant Cell 15: 93–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Galletti R, Vairo D, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. 2006. Antisense expression of the Arabidopsis thaliana AtPGIP1 gene reduces polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein accumulation and enhances susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 19: 931–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca S, Chini A, Hamberg M, et al. 2009. (+)-7-iso-Jasmonoyl-l-isoleucine is the endogenous bioactive jasmonate. Nature Chemical Biology 5: 344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Fujita Y, Noutoshi Y, et al. 2006. Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: a current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 9: 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukusaki E, Jumtee K, Bamba T, Yamaji T, Kobayashi A. 2006. Metabolic fingerprinting and profiling of Arabidopsis thaliana leaf and its cultured cells T87 by GC/MS. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung, Series C 61: 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gális I, Gaquerel E, Pandey SP, Baldwin IT. 2009. Molecular mechanisms underlying plant memory in JA-mediated defence responses. Plant, Cell and Environment 32: 617–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J, Chen W, Estes B, et al. 2003. Topology of the network integrating salicylate and jasmonate signal transduction derived from global expression phenotyping. The Plant Journal 34: 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda H, Sasaki E, Akiyama K, et al. 2008. The AtGenExpress hormone and chemical treatment data set: experimental design, data evaluation, model data analysis and data access. The Plant Journal 55: 526–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens A, Hakkinen ST, Laakso I, et al. 2003. A functional genomics approach toward the understanding of secondary metabolism in plant cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 100: 8595–8600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubet F, Barton CJ, Mortimer JC, et al. 2009. Cell wall glucomannan in Arabidopsis is synthesised by CSLA glycosyltransferases, and influences the progression of embryogenesis. The Plant Journal 60: 527–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg J, Jonsson P, Nordstrom A, Sjostrom M, Moritz T. 2004. Design of experiments: an efficient strategy to identify factors influencing extraction and derivatization of Arabidopsis thaliana samples in metabolomic studies with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Analytical Biochemistry 331: 283–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann T, Bennett M, Mansfield J, Somerville C. 2009. Identification of cell-wall stress as a hexose-dependent and osmosensitive regulator of plant responses. The Plant Journal 57: 1015–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanik N, Gómez S, Schueller M, Orians CM, Ferrieri RA. 2010. Use of gaseous 13NH3 administered to intact leaves of Nicotiana tabacum to study changes in nitrogen utilization during defence induction. Plant, Cell and Environment 33: 2173–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hématy K, Cherk C, Somerville S. 2009. Host–pathogen warfare at the plant cell wall. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 12: 406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrawati O, Yao Q, Kim HK, et al. 2006. Metabolic differentiation of Arabidopsis treated with methyl jasmonate using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Plant Science 170: 1118–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Blanco C, Feng DX, Hu J, et al. 2007. Impairment of cellulose synthases required for arabidopsis secondary cell wall formation enhances disease resistance. The Plant Cell 19: 890–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GA, Jander G. 2008. Plant immunity to insect herbivores. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59: 41–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, et al. 2008. Genevestigator V3: a reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Advances in Bioinformatics 2008: 420747. doi: 10.1155/2008/420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel J, Strehmel N, Selbig J, Walther D, Kopka J. 2010. Decision tree supported substructure prediction of metabolites from GC-MS profiles. Metabolomics 6: 322–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasukabe Y, He L, Nada K, Misawa S, Ihara I, Tachibana S. 2004. Overexpression of spermidine synthase enhances tolerance to multiple environmental stresses and up-regulates the expression of various stress-regulated genes in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant and Cell Physiology 45: 712–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausch KD, Sobolev AP, Goyal RK, et al. 2012. Methyl jasmonate deficiency alters cellular metabolome, including the aminome of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruit. Amino Acids 42: 843–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YB, Kim JK, Uddin MR, et al. 2013. Metabolomics analysis and biosynthesis of rosmarinic acid in Agastache rugosa Kuntze treated with methyl jasmonate. PLoS One 8: e64199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koda Y. 1997. Possible involvement of jasmonates in various morphogenic events. Physiologia Plantarum 100: 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva OA, Tomlinson M, Parinyapong P, et al. 2004. CycD1, a putative G1 cyclin from Antirrhinum majus, accelerates the cell cycle in cultured tobacco BY-2 cells by enhancing both G1/S entry and progression through S and G2 phases. The Plant Cell 16: 2364–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchitsu K, Yazaki Y, Sakano K, Shibuya N. 1997. Transient cytoplasmic pH change and ion fluxes through the plasma membrane in suspension-cultured rice cells triggered by N. Plant and Cell Physiology 38: 1012–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Kusano T, Berberich T, Tateda C, Takahashi Y. 2008. Polyamines: essential factors for growth and survival. Planta 228: 367–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti V, Raiola A, Camardella L, et al. 2007. Overexpression of pectin methylesterase inhibitors in Arabidopsis restricts fungal infection by Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiology 143: 1871–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti V, Francocci F, Ferrari S, et al. 2010. Engineering the cell wall by reducing de-methyl-esterified homogalacturonan improves saccharification of plant tissues for bioconversion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107: 616–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti V, Cervone F, Bellincampi D. 2012. Methyl esterification of pectin plays a role during plant–pathogen interactions and affects plant resistance to diseases. Journal of Plant Physiology 169: 1623–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major IT, Campos ML, Moreno JE. 2017a The role of specialized photoreceptors in the protection of energy‐rich tissues. Agronomy 7: 23. doi: 10.3390/agronomy7010023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Major IT, Yoshida Y, Campos ML, et al. 2017. b Regulation of growth–defense balance by the JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ)-MYC transcriptional module. New Phytologist 215: 1533–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfield IW, Orfila C, McCartney L, et al. 2004. Novel cell wall architecture of isoxaben-habituated Arabidopsis suspension-cultured cells: global transcript profiling and cellular analysis. The Plant Journal 40: 260–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur J, Koncz C, Szabados L. 1995. A simple method for isolation, liquid culture, transformation and regeneration of Arabidopsis thaliana protoplasts. Plant Cell Reports 14: 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Zipfel C, Rowland O, Keller I, Robatzek S, Boller T, Jones JDG. 2004. The transcriptional innate immune response to flg22. Interplay and overlap with Avr gene-dependent defense responses and bacterial pathogenesis. Plant Physiology 135: 1113–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndimba BK, Chivasa S, Hamilton JM, Simon WJ, Slabas AR. 2003. Proteomic analysis of changes in the extracellular matrix of Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures induced by fungal elicitors. Proteomics 3: 1047–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noir S, Bömer M, Takahashi N, et al. 2013. Jasmonate controls leaf growth by repressing cell proliferation and the onset of endoreduplication while maintaining a potential stand-by mode. Plant Physiology 161: 1930–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JA, Daudi A, Finch P, et al. 2012. A peroxidase-dependent apoplastic oxidative burst in cultured Arabidopsis cells functions in MAMP-elicited defense. Plant Physiology 158: 2013–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakenfull EA, Riou-Khamlichi C, Murray AH. 2002. Plant D-type cyclins and the control of G1 progression. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 357: 749–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parre E, Geitmann A. 2005. Pectin and the role of the physical properties of the cell wall in pollen tube growth of Solanum chacoense. Planta 220: 582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil RA, Lenka SK, Normanly J, Walker EL, Roberts SC. 2014. Methyl jasmonate represses growth and affects cell cycle progression in cultured Taxus cells. Plant Cell Reports 33: 1479–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M, Keegstra K. 2016. Biosynthesis of the plant cell wall matrix polysaccharide xyloglucan. Annual Review of Plant Biology 67: 235–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels L, Morreel K, De Witte E, et al. 2008. Mapping methyl jasmonate-mediated transcriptional reprogramming of metabolism and cell cycle progression in cultured Arabidopsis cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105: 1380–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Amador MA, Leon J, Green PJ, Carbonell J. 2002. Induction of the arginine decarboxylase ADC2 gene provides evidence for the involvement of polyamines in the wound response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 130: 1454–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team 2011. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Ricaud L, Proux C, Renou JP, et al. 2007. ATM-mediated transcriptional and developmental responses to γ-rays in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 2: 3e430. doi: 10.1371/.pone.0000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rischer H, Oresic M, Seppänen-Laakso T, et al. 2006. Gene-to-metabolite networks for terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 103: 5614–5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar P, Bosneaga E, Auer M. 2009. Plant cell walls throughout evolution: towards a molecular understanding of their design principles. Journal of Experimental Botany 60: 3615–3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nature Protocols 3: 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9: 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard LB, Tan X, Mao H, et al. 2010. Jasmonate perception by inositol-phosphate-potentiated COI1–JAZ co-receptor. Nature 468: 400–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suza WP, Avila CA, Carruthers K, Kulkarni S, Goggin FL, Lorence A. 2010. Exploring the impact of wounding and jasmonates on ascorbate metabolism. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48: 337–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Światek A, Lenjou M, Van Bockstaele D, Inzé D, Van Onckelen H. 2002. Differential effect of jasmonic acid and abscisic acid on cell cycle progression in tobacco BY-2 cells. Plant Physiology 128: 201–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Światek A, Azmi A, Stals H, Inzé D, Van Onckelen H. 2004. Jasmonic acid prevents the accumulation of cyclin B1;1 and CDK-B in synchronized tobacco BY-2 cells. FEBS Letters 572: 118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DB, Cosgrove DJ. 2009. Dynamic coordination of cytoskeletal and cell wall systems during plant cell morphogenesis. Current Biology 19: R800–R811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taurino M, Abelenda JA, Río-Alvarez I, et al. 2014. Jasmonate-dependent modifications of the pectin matrix during potato development function as a defense mechanism targeted by Dickeya dadantii virulence factors. The Plant Journal 77: 418–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanh NT, Murthy HN, Yu KW, Hahn EJ, Paek KY. 2005. Methyl jasmonate elicitation enhanced synthesis of ginsenoside by cell suspension cultures of Panax ginseng in 5-l balloon type bubble bioreactors. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 67: 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thines B, Katsir L, Melotto M, et al. 2007. JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCFCOI1 complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 448: 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanowicz BR, Bennett AB, del Campillo E, et al. 2007. Structural organization and a standardized nomenclature for plant endo-1,4-beta-glucanases (cellulases) of glycosyl hydrolase family 9. Plant Physiology 144: 1693–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leene J, Hollunder J, Eeckhout D, et al. 2010. Targeted interactomics reveals a complex core cell cycle machinery in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular Systems Biology 6: 397. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Liu G, Niu H, Timko MP, Zhang H. 2014. The F-box protein COI1 functions upstream of MYB305 to regulate primary carbohydrate metabolism in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. TN90). Journal of Experimental Botany 65: 2147–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Hause B. 2013. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Annals of Botany 111: 1021–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler EW, Kutchan TM, Gorba T, Brodschelm W, Niesel U, Bublitz F. 1994. The Pseudomonas phytotoxin coronatine mimics octadecanoid signalling molecules of higher plants. FEBS Letters 345: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal L, Scheel D, Rosahl S. 2008. The coi1-16 mutant harbors a second site mutation rendering PEN2 nonfunctional. The Plant Cell 20: 824–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willats WGT, Orfila C, Limberg G, et al. 2001. Modulation of the degree and pattern of methyl-esterification of pectic homogalacturonan in plant cell walls: implications for pectin methyl esterase action, matrix properties, and cell adhesion. Journal of Biological Chemistry 276: 19404–19413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolucka BA, Goossens A, Inzé D. 2005. Methyl jasmonate stimulates the de novo biosynthesis of vitamin C in plant cell suspensions. Journal of Experimental Botany 56: 2527–2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Baldwin IT. 2010. New insights into plant responses to the attack from insect herbivores. Annual Review of Genetics 44: 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]