Abstract

Fear discrimination is critical for survival, while fear generalization is effective for avoiding dangerous situations. Overgeneralized fear is a typical symptom of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Previous research demonstrated that fear discrimination learning is mediated by prefrontal mechanisms. While the prelimbic (PL) and infralimbic (IL) subdivisions of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) are recognized for their excitatory and inhibitory effects on the fear circuit, respectively, the mechanisms driving fear discrimination are unidentified. To obtain insight into the mechanisms underlying context-specific fear discrimination, we investigated prefrontal neuronal ensembles representing distinct experiences associated with learning to disambiguate between dangerous and similar, but not identical, harmless stimuli. Here, we show distinct quantitative activation differences in response to conditioned and generalized fear experiences, as well as modulation of the neuronal ensembles associated with successful acquisition of context-safety contingencies. These findings suggest that prefrontal neuronal ensembles patterns code functional context-danger and context-safety relationships. The PL subdivision of the mPFC monitors context-danger associations to conditioned fear, whereas differential conditioning sparks additional ensembles associated with the inhibition of generalized fear in both the PL and IL subdivisions of the mPFC. Our data suggest that fear discrimination learning is associated with the modulation of prefrontal subpopulations in a subregion- and experience-specific fashion, and the learning of appropriate responses to conditioned and initially generalized fear experiences is driven by gradual updating and rebalancing of the prefrontal memory representations.

Keywords: medial prefrontal cortex, fear inhibition, fear discrimination learning, memory ensemble, context-dependent fear conditioning, fear generalization

1. Introduction

Survival relies on the ability to discriminate between danger and safety. Fear discrimination learning is of clinical importance, as there is growing evidence that the failure to subdue fear under safe conditions is a primary symptom found in people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Jovanovic et al., 2010b; Jovanovic et al., 2010a; Jovanovic et al., 2013). Human imaging studies of functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex an amygdala demonstrated impaired inhibition of the amygdala in PTSD (Lanius et al., 2004). Others found elevated amygdala activity associated with PTSD without any obvious changes in the prefrontal inhibition (Gilboa et al., 2004). Thus, understanding prefrontal mechanisms underlying safety signal processing during fear discrimination learning is relevant to normal and abnormal brain function.

The Hull-Spence continuity theory of discrimination learning postulates that conditioned excitation (the result of reinforcement) and inhibition (the result of nonreinforcement) have generalization gradients and that discrimination learning is the summation of excitation and inhibition (Spence, 1937; Hull, 1952; Klein, 2014). On the other hand, widely recognized multiple memory systems theory postulates that different types of memory are consolidated via hardwired pathways (Squire, 1986). Studies of the circuitry mediating fear modulation reveal that fear behavior is differentially regulated by the prelimbic (PL) and infralimbic (IL) regions of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2006; Quirk et al., 2008; Sierra-Mercado et al., 2010; Courtin et al., 2013) via fear excitation and inhibition, respectively (Sierra-Mercado et al., 2010; Sotres-Bayon et al., 2010), which may be due to differential connectivity with the amygdala (Vertes, 2004; Gabbott et al., 2005).

During contextual fear conditioning, associations between a contextual stimulus (conditioned stimulus, CS) and a foot shock (unconditioned stimulus, US) are directly encoded via synaptic plasticity in the amygdala, which receives direct inputs from the hippocampus (Hip) (Fanselow et al., 2015). The fact that expression of recent and remote long-term fear memories requires the dorsal Hip (dHip) and mPFC, respectively, suggests that the communication between these two brain regions controls the transition from a recent state to a remote state during system-level memory consolidation (Squire, 1986; Kim et al., 1992; Frankland et al., 2004; Quinn et al., 2008; Kitamura et al., 2017). While the dHip and mPFC appear to track spatial information, the mPFC is likely to integrate contextual recognition of context-danger associations with distinctive roles infralimbic (IL) and prelimbic (PL) subregions of the mPFC (Frankland et al., 1998; Zelikowsky et al., 2014). Thus, both dHip and mPFC appear to be engaged in context coding related to defensive behaviors, and context-specific neuronal ensembles are found in both regions (Euston et al., 2012; Hyman et al., 2012).

The mPFC networks have been strongly implicated in fear modulation, including extinction (Quirk et al., 2000; Milad et al., 2002; Quirk et al., 2003), fear renewal (Knapska et al., 2009) (Orsini et al., 2011) and fear discrimination (Zelikowsky et al., 2013; Vieira et al., 2014; Vieira etal., 2015). The mPFC appears to play a critical role in the decoding differences between dangerous and generalized stimuli that drive the acquisition of the differential fear responses, including some molecular mechanisms that underlie this role. In fact, well-defined key molecular mediators of long-term memory consolidation in the mPFC, such as the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, CREB and CREB-binding protein (CBP)’s intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity, are all required for successful discriminative fear learning (Vieira et al., 2014; Vieira et al, 2015), consistent with the idea that new memory encoding within the prefrontal network drives fear inhibition.

While the circuit-, cellular- and molecular-level mechanisms of fear extinction have been extensively studied in the mPFC, how the neural circuitry of the mPFC contributes to fear discrimination learning is unknown. In this study, we examined prefrontal neuronal ensembles representing distinct experiences associated with learning to distinguish between dangerous and similar, but not identical, safe stimuli. These data revealed prefrontal subdivision-specific patterns of neuronal activation, distinct quantitative activation differences in response to dangerous and harmless experiences, and the formation of overlapping neuronal ensembles associated with successful fear discrimination learning. Evidence from context-dependent fear discrimination learning tasks indicated that substantial changes in population activity patterns occurred within distinct subdivisions of the mPFC during differential conditioning.

Unexpectedly, not only the IL but also PL cortex mediated safety learning, supporting the idea that both these cortical regions cooperate in properly gating context-danger and context-safety contingencies during top-down control of appropriate fear responses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

The UC Riverside Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. The bi-transgenic TetTag mice were generated by breeding knock-in Arc-tTA homozygotes (generated on the C57BL/J6 background) carrying a tTA knockin insertion downstream from the Arc gene promoter with transgenic Tg(tetO-HIST1H2BJ/GFP)47Efu mice (Tumbar et al., 2004). Tg(tetO-HIST1H2BJ/GFP)47Efu mice were generated by introducing the transgenic construct to CD-1 donor eggs and the hemizygous line was maintained on the C57BL/J6 background. Mice were weaned at postnatal day 21 and were housed, 4 animals to a cage, with same-sex littermates. Mice had ad libitum access to food and water and were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle.Old bedding was exchanged for fresh autoclaved bedding every week. Mice were raised on a 40 mg/kg Dox diet (BioServ, Inc, Custom Made Cat No F-3958) since gestation to prevent GFP expression before experimental manipulations. To label active neurons during Event 1 (see Figure 1A), the food diet was changed to regular food chow not containing Dox. To prevent GFP expression after Event 1, we have switched food died to food chow containing high levels of Dox (1g/kg) (BioServ, Inc, Custom Made Cat No F-7363) These levels of Dox were effective in turning off expression of GFP (Reijmers et al., 2007; Cai et al., 2016). Seizure was induced by pentylenetetrazole (PTZ, 50mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection).

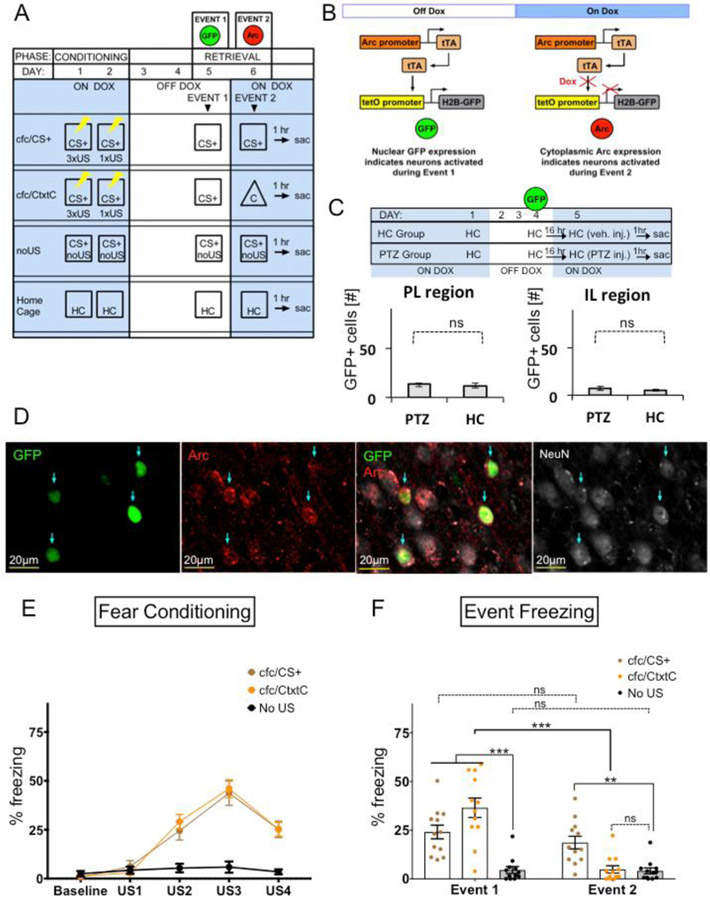

Figure 1.

Genetic tagging of neuronal ensembles activated during two distinct events using the Arc-driven TetTag system and endogenous Arc gene expression. (A) Animals were fear conditioned to CS+, then exposed to conditioned stimuli, CS+, during first memory retrieval (Event 1), and then exposed either to CS+ again (cfc/CS+ group) or to a very different context, CtxtC (cfc/CtxtC). The noUS group was exposed to the same context as CS+ but without foot shocks (US) and then underwent the same testing as cfc/CS+ group. Home cage indicates animals were housed in their home cage during the duration of the assay. (B) This study used bi-transgenic mutants, in which the Arc promoter drove the expression of the tetracycline-controlled transactivator protein (tTA), which binds to the tetracycline-responsive promoter element (tetO), driving the expression of a fusion protein composed of histone 2B and green fluorescent protein (H2B-GFP) in activated neurons. Indelible labelling of transiently activated neurons during specific experiences was controlled by a doxycycline (Dox) diet. When animals were taken off Dox, neurons activated during Event 1 were labelled with GFP. Neurons activated during Event 2 were revealed by assessment of endogenous Arc expression. (C) Dox diet was effective in blocking GFP expression in the brain. In this experiment, mice were removed from regular Dox diet (40 mg/kg) similarly as shown in Fig 1A and given regular food chow diet for 3 days. 16 hours after switching to high Dox food diet (1 gm/kg), mice were injected with 30mg/kg of pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) and tested 1 hr later for levels of GFP expression in the mPFC. Home cage (HC) refers to mice that underwent the same Dox treatment as the PTZ mice but did not receive PTZ injection. Y-axis label “GFP+ cells [#]” refers to a number of GFP-positive cells found in PL (left) or IL (right). There was no difference in PL activity measured in HC (M=12 ± 2.352, n=6) and PTZ (M=13.22 ± 1.701, n=3) conditions; t(7)=0.3387, p=0.7448, r=−0.133. In addition, there was no difference in IL activity measured in HC (M=5.607 ± 1.073, n=6) and PTZ (M=7 ± 2.211, n=3) conditions; t(7)=0.6522, p=0.5351, r=0.131. (D) Representative images taken from the same region in the mPFC showing a comparison between permanently GFP-labelled neurons during Event 1 (GFP, green) and endogenous Arc gene expression during Event 2 (Arc, red). An overlap of GFP and Arc images reveal neurons activated during both Event 1 and Event 2. Cell identity is revealed via expression of a neuronal marker (NeuN). Representative images were acquired as a single optical section using 40X magnification with a digital zoom of 3.0 in the PL. Blue arrows indicate overlapping neurons activated during both Event 1 and Event 2. Scale bars indicate 20 μm. (E) The cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups were successfully fear conditioned. RM two-way ANOVA of Group and US followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison reveled robust fear acquisition compared to the noUS group (Group × US: F(8, 132) = 13.97, P<0.0001; Group: F(4, 132) = 65.47, P<0.0001; US, F(2, 33) = 18.4, P<0.0001 (Baseline: cfc/CS+ vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.9903, cfc/CS+vs. noUS, P=0.9184, cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, P=0.963; US1: cfc/CS+ vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.7502, cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P=0.9101; cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, P=0.9486; US2: cfc/CS+ vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.5577, cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P=0.0001, cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, <0.0001; US3: cfc/CS+ vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.868, cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P=<0.0001, cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, P=<0.0001; US4: cfc/CS+vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=>0.9999, cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P=<0.0001, cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, P=<0.0001. (F) cfc/CtxtC mice show differential responses to two different stimuli: CS+ and CtxtC. After fear conditioning (Fig 1E), the cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups were exposed to conditioned stimuli CS+ during first memory retrieval (Event 1), and then exposed either to CS+ again (cfc/CS+ group) or to a very different context, CtxtC (cfc/CtxtC), respectively. While the cfc/CtxtC group showed high fear in response to CS+ during Event 1 and low fear in response to CtxtC during Event 2, the cfc/CS+ group showed similar levels of fearful responses during both events. The noUS group was not fear conditioned and showed no fear throughout the conditioning phase. RM two-way ANOVA of Group and US followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons showed that the cfc/CtxtC group distinguished between two different contextual stimuli: CS+ and CtxtC. (Group × US: F (2, 33) = 20.9, P<0.0001; US: F (1, 33) = 34.84, P<0.0001; Group: F (2, 33) = 15.24, P<0.0001. Event 1 - Event 2: cfc/CS+, P=0.3819; cfc/CtxtC, P<0.0001; noUS, P=0.9993. Event 1: cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P<0.0001, cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, P<0.0001; Event 2: cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P=0.0042; cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, P=0.9976). Significance values were set at p < 0.05: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 and ns not significant.

2.2. Contextual fear conditioning assay (CFC)

Mice between 2 and 6 months of age were individually housed. Mice were then handled once a day for three days before starting the CFC assay shown on diagram (Fig 1A). All fear conditioning was performed in a fear conditioning box (Lafayette Instrument Co.) placed in a sound-attenuating chamber, and performance was analysed automatically using a video-based system controlled by FreezeFrame v. 4 software (Actimetrics). On day 1, animals were exposed to three US (foot shock, 2 sec, 0.75 mA) in context CS+ after a 180 sec baseline with a 90 sec inter-trial interval (ITI) and a 60 sec post-shock period. On day 2, animals were exposed to 1xUS in context CS+ after a 180 sec baseline with 60 sec post-shock period. During days 3-5, animals were taken off Dox diet. On Day 5, animals were exposed to CS+ for 300 sec then placed back on high dose Dox (1mg/kg) diet for the remainder of the assay. On Day 6, animals were exposed to either conditioned context stimuli CS+ (cfc/CS+ group) or novel stimuli CtxtC (cfc/CtxtC group) for 300 sec then immediately placed back in their home cage and sacrificed 1 hr later. The noUS mice underwent the same procedure as cfc/CS+ mice with the exception that this group was never exposed to US. Home Cage animals were given the same Dox treatment as other groups but remained in their home cage for the entirety of the assay. All freezing, expressed as "% freezing", is calculated as the percentage of time spent freezing during 180 sec of context exposure. The box was cleaned between trials with 70% ethanol and with water.

2.3. Contextual fear discrimination assay (DC)

The contextual fear discrimination assay is divided into the following parts: habituation, fear conditioning and differential conditioning divided into two phases: early discrimination and late discrimination (see Fig 3A). In the habituation phase, animals were exposed to each tested context stimuli (CS+, CS−, CtxtC) without US for 10 min a day for three days before starting the assay. On the first day of fear conditioning training (day 1), animals were exposed to three foot shocks (2 sec, 0.75mA) in CS+ after 180 sec baseline with 90 sec inter trial interval and 60 sec post-shock period. During the second day of fear conditioning (day 2), animals were exposed to 1xUS in context CS+ after a 180 sec baseline with 60 sec post-shock period. On the first day of early discrimination (day 3), animals were exposed to CS+ paired with US then CS− (not paired) for an equal amount of time (242 sec). During days 4-6, animals were taken off Dox diet. On Day 6, animals were exposed to one of tested stimuli (CS+, CS− or CtxtC) without any reinforcement for 300 sec then placed back on high dose Dox (1mg/kg) diet for the remainder of the assay. During differential conditioning (days 7-11), animals were exposed to CS+, CS− and CtxtC in alternating order for equal amounts of time (242 sec). During days 7-11, animals never received US during exposure to CS− and CtxtC, while exposure to CS+ was paired with US (foot shock, 2 sec, 0.75mA) delivered 180 sec after placing animals in context CS+. On day 12, animals were re-exposed to their test context for 300 sec without any reinforcement, immediately placed back in their home cage and sacrificed 1 hr later. Discrimination index was calculated using the freezing responses to CS+ and CS− according to the formula DI=[(% freezing to CS+) – (% freezing to CS−)]/[(% freezing to CS+) + (% freezing to CS−)].

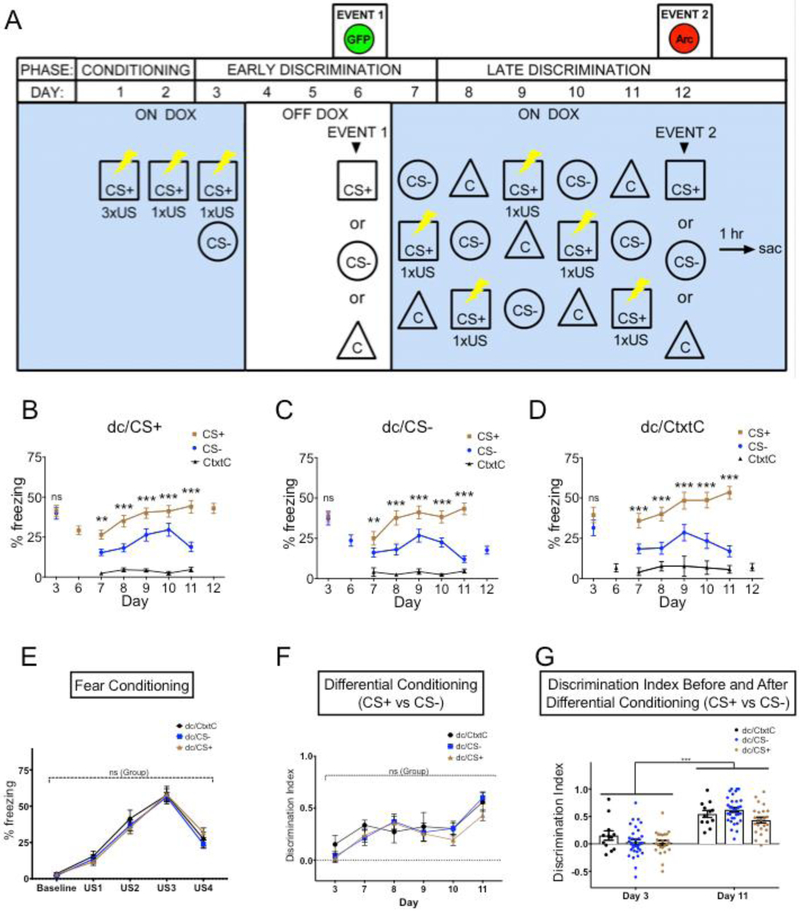

Figure 3.

Tested groups show robust performance on a contextual fear discrimination learning task. (A) The context-dependent fear discrimination learning assay consists of three phases: fear conditioning, fear generalization (Early Discrimination) followed by additional differential conditioning (Late Discrimination). Details are described in the test. All three groups, (B) the dc/CS+, (C) dc/CS− and (D) dc/CtxtC groups showed robust performance on differential fear conditioning. (B) dc/CS+, RM two-way ANOVA of Day (Days 3, 7-11) and Context (CS+, CS−) followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons: Day F (5, 115) = 16.82 P<0.0001; Context F (1, 23) = 84 P<0.0001; Day × Context F (5, 115) = 7.006 P<O.000. CS+vs. CS−: Day 3, P= 0.9964; Day P= 0.0015; Day 8, P= < 0.0001; Day 9, P=< 0.0001; Day 10, P= 0.0008; Day 11, P=<0.0001. There was a significant difference in freezing to CS− for Day 3 (M=39.93 +/−3.68) and Day 11 (M=18.88 +/−2.9) conditions; t(23)=6.97, p<0.0.0001, r=−0.541. There was no difference in freezing to CS+ for Day 3 (M=41.43 +/−339) and Day 11 (M=43.96 +/−3.9) conditions; t(23)=−0.73, p=0.472, r=0.070. (C) dc/CS−, RM two-way ANOVA of Day (Days 3, 7-11) and Context (CS+, CS−) followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons: Day , F (5, 155) = 15.21, P<0.0001; Context, F (1, 31) = 81.3,1, P<0.0001; Day × Context, F (5, 155) = 14.47, P<0.0001 CS+ vs. CS−: Day 3, P= 0.9938; Day 7, P= 0.0065; Day 8, P<0.0001; Day 9, P<0.0001; Day 10, P<0.0001; Day 11, P<0.0001. There was a significant difference in freezing to CS− for Day 3 (M=37.16 +/−3.85) and Day 11 (M=12.07 +/−2.05) conditions; t(31)=7.35, p<0.0.0001, r=−0.584. There was no difference in freezing to CS+ for Day 3 (M=38.67 +/−3.34) and Day 11 (M=43.27 +/−3.57) conditions; t(31)=7.35, p=0.151, r=0.117 (D) dc/CtxtC, RM two-way ANOVA of Day (Days 3, 7-11) and Context (CS+, CS−) followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons: Day, F (5, 55) = 4.539 P=0.0016; Context, F (1, 11) = 53.99 P<0.0001; Day × Context, F (5, 55) = 6.024 P=0.0002. CS+ vs. CS−: Day 3, P= 0.2214; Day 7, P= 0.0002; Day P<0.0001; Day 9, P<0.0001; Day 10, P<0.0001; Day 11, P<0.0001. There was a significant difference in freezing to CS− for Day 3 (M=31.51 +/−4.80) and Day 11 (M=16.97+/− 3.41) conditions; t(11)=3.654, p<0.0038, r=−0.450. There was a significant difference in freezing to CS+ for Day 3 (M=39.48 +/−4.77) and Day 11 (M=53.27 +/−3.9) conditions; t(11)=4.138, p=0.0017, r=0.415 (E) The dc/CS+, dc/CS−, and dc/CtxtC groups showed robust performance on the fear conditioning. RM two-way ANOVA of Group and US followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison revealed robust fear acquisition in all three groups. Group × US: P= 0.671, US, P <0.0001, Group, P 0.7484. Baseline: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.9732; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9983; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9771. US1: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.9241; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.7635; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.8977. US2: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.6739; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.5111; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9212. US3: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.9635; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9976; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9105. US4: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.7876; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.7238; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.1617. (F) The dc/CS+, dc/CS−, and dc/CtxtC groups showed similar level of performance on differential fear discrimination. RM two-way ANOVA of Group x Day (Days 3, 7-11) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison revealed the same performance in all three groups. Group × Day: P= 0.8098; Day, P <0.0001; Group, P= 0.3177. Day 3: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.5661; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.5099; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9834. Day 7: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.5434; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.7056; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9581. Day 8: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.665; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.7621; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.986. Day 9: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.8891; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.841; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9868. Day 10: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= >0.9999; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.6363; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.4526. Day 11: dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.9312; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.5401; dc/CS− vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.1587. (G) The dc/CS+, dc/CS−, and dc/CtxtC groups showed generalized fear responses to CS− on Day 3 and but successful fear discrimination by Day 11 (CS+ vs CS−).When comparing the first day of early discrimination with the last day of late discrimination, all three groups showed a robust discrimination index on Day 11 9 (CS+ vs CS−) but these groups were not able to discriminate between CS+ and CS− on Day 3. RM two-way ANOVA of Group and Day 3/11 followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons: Group × Event: P= 0.0741; Event, P<0.0001; Group, P 0.0871. Day 3 vs Day 11: dc/CtxtC, P= 0.0002; dc/CS−, P= <0.0001; dc/CS+, P <0.0001. However, there were no differences in Discrimination Indexes (CS+ vs CS−) between groups on Day 3 or Day 11 (P-values not shown). The discrimination index (DI) was calculated using the freezing responses to CS+ and CS− according to the formula DI=[(% freezing to CS+) – (% freezing to CS−)]/[(% freezing to CS+) + (% freezing to CS−)]. Significance values were set at p < 0.05: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 and ns not significant.

2.4. Context description

Context CS+ was a 12.0" L x 10.2" D x 12.0" H fear conditioning box (Lafayette Instrument Co.) housed in a sound-attenuating chamber. Modalities included a constant 400 ms frequency-modulated sweep, logarithmically modulated between 2 and 9 kHz and delivered at 0.5 Hz, lemon extract scent, uniform shock bars, a ventilation fan and a house light.

Context CS− was a 12.0" L x 10.2" D x 12.0" H fear conditioning box (Lafayette Instrument Co.) located within a sound-attenuated chamber. Modalities included black and white vertical striped walls, a constant 2.8 kHz tone, vanilla extract scent, uniform shock bars, a ventilation fan and a house light. Context CtxtC was a 9" L x 6" D x 6.5" plastic box with Sani-Chips bedding located in a fear conditioning chamber (Lafayette Instrument Co.). Modalities included a ventilation fan and a house light. CS+ and CS− are designed to be similar yet distinct while CtxtC is substantially different and served as a neutral context. While CS+ predicted US, CS− and CtxtC did not predict US.

2.5. Histology

Mice were sacrificed using Nembutal (200 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) and transcardially perfused with 20 ml of PBS and then with 20 ml of 4% PFA. Brains were extracted, soaked in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C and then soaked in 20% sucrose at 4°C until the brains sank. The brains were then flash-frozen in embedding media (Tissue-Tek, 4583) using dry ice and ethanol before being stored at −80°C. Free-floating 40 μm coronal sections were sliced using a cryostat (Leica, CM1860) and stored in cryoprotectant (50% PBS, 30% ethylene glycol, 20% glycerol) at −20°C. Free-floating immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed by washing sections 2 times for 10 min in 1x PBS followed by a 1 h incubation in blocking buffer (4% normal goat serum in washing buffer) then washing 3 times for 10 min in washing buffer (1x PBS w/ 0.3% Triton X-100). The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in antibody diluent (2% normal goat serum in washing buffer) with primary antibodies (chicken anti-GFP polyclonal antibody, Thermo Fisher, A10262, 1:2000; mouse anti-NeuN monoclonal antibody, Millipore, MAB377, 1:2000; rabbit anti-Arc polyclonal antibody, Synaptic Systems, 156-003, 1:2500). After three washes with washing buffer, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa488 goat anti-chicken IgG, Thermo Fisher, A-11039, 1:1000;, Alexa568 goat anti-mouse IgG, Thermo Fisher, A-11031, 1:1000; Alexa647 donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Thermo Fisher, A-31573, 1:1000) for 3 hr at room temperature in antibody diluent. The sections were then washed once with washing buffer for 10 min and then incubated with DAPI (Invitrogen, D1306, 1:1000) for 15 mins. Sections were then washed twice with 1x PBS for 10 min. Sections were mounted on glass slides (Superfrost Plus, 12-550-15) using mounting medium (ProLong Antifade, P36965) before imaging.

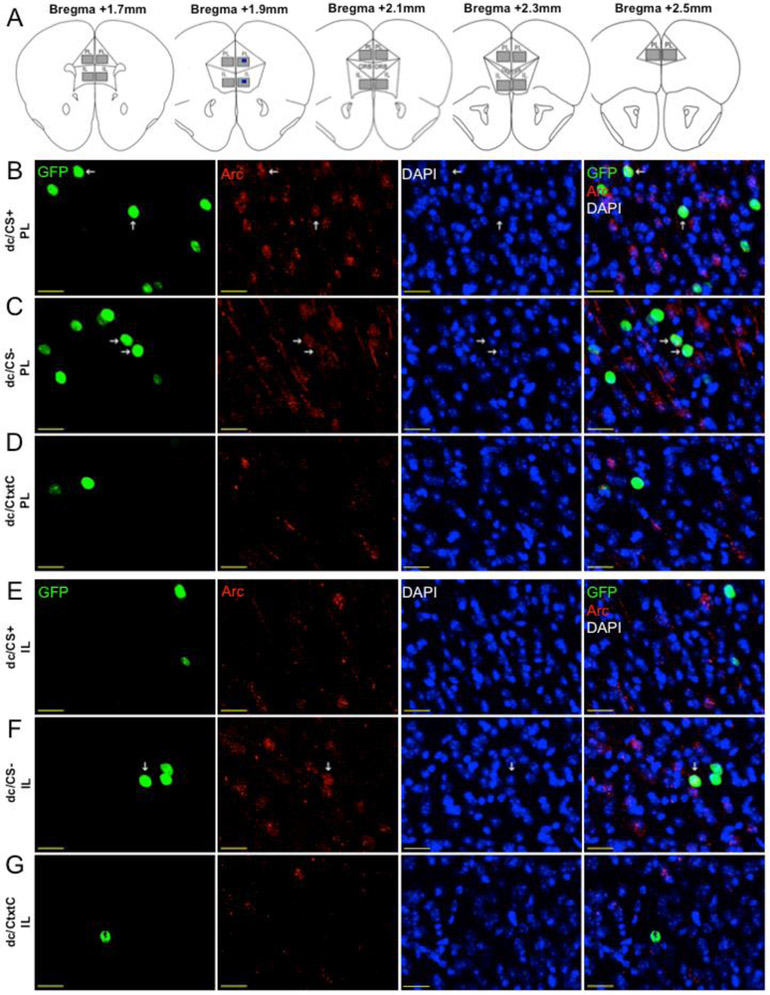

2.6. Imaging

Coronal sections from 2.5 mm to 1.7 mm anterior to bregma were imaged at 20x (20x/0.95 XLUMPlcinFl objective) magnification using a semi-automatic laser-scanning confocal Olympus FV1000 microscope controlled by Olympus FV10-ASW software (v. 2.01). The gain and offset of each channel were balanced manually using Fluoview saturation tools for maximal contrast. All settings were tested on multiple slices before data collection and brain slices were imaged using identical microscope settings once established. Each channel was acquired in “Sequential Mode, Frame”. All images were acquired using the “Integration Type: Line Kalman” and “Integration Count: 2” in order to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. Localization of the PL and IL regions within the mPFC was performed by overlaying images from the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas. For quantification, 10 optical sections were acquired from a 30 μm Z-stack encompassing both superficial and deep layers. GFP-positive (GFP+), Arc-positive (Arc+) and total number of cells (DAPI+ cells) per image were counted by an experimenter who was blind to the treatment status. For reactivation, GFP+ and Arc+ (GFP+ ∩ Arc+) overlap was counted only when the Arc signal and GFP signal came from the same cell over multiple optical sections. Images were quantified from both hemispheres of 5-9 anatomically matched sections per animal through the entire rostrocaudal axis of the mPFC. The number of GFP+ cells, number of Arc+ cells and percentage of overlap were calculated per image and then averaged to produce a single measurement per animal. Mean ± SEM of the total number of DAPI-positive nuclei per image from PL and IL were counted from 3–5 coronal sections per mouse (n=4). Mean ± SEM of Activation and Reactivation Rates were calculated per image as follows: Event 1 activation rate (GFP+ cells) was calculated as # of GFP+ cells per image. Event 2 activation rate (Arc+ neurons) was calculated as # of Arc+ neurons per image. Reactivation Rate (Overlapping Ensemble) was calculated as [(GFP+ cells ∩ Arc+ cells)/Arc+ cells] x 100 per image. We have also compared measured reactivation index (calculated as [(GFP+ cells ∩ Arc+ cells)/DAPI+cells] x 100 per image) to a predicted reactivation index calculated as a chance, where the chance was calculated as CHANCE = (GFP+ cells/DAPI+ cells) * (Arc+ cells/DAPI+ cells) * 100. All significant reactivation indexes that are reported in the manuscript were substantially higher than the calculated chance.

2.7. Data analysis

Experimenters were blind to group designations. The data represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism and Excel (Microsoft, Inc.). Student’s t test or ANOVA was used for statistical comparisons. Pearson’s correlation (r) was used as an effect size. For one-way ANOVA, eta-squared (η2) was used as an effect size. For learning assessment during fear conditioning and differential conditioning, repeated measures (RM) ANOVA and post hoc analysis with Tukey’s's multiple comparisons test was used. Analysis of neuronal ensemble activation and reactivation was performed using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons post hoc test. In order to compare neuronal activations between events during exposure and re-exposure to a specific stimulus, we performed RM ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons Sidak’s post hoc test. In order to compare neuronal activation or reactivation between brain regions during exposure and re-exposure to a specific stimulus, we performed ordinary two-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons Sidak’s post hoc test. Comparison with chance level was done using one sample t-test and an effect size. The relationship between the activation rate or the reactivation index and behavioral performance was measured by simple linear correlations (Pearson correlation). Significance values were set at p < 0.05. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 and ns or absence of asterisk(s) indicates not significant.

3. Results

3.1. Fear memory retrieval triggers PL neural ensemble of context-danger association.

Context-sensitive fear learning and modulation involve the amygdala-hippocampus-mPFC circuitry (Jin et al., 2015b). The prefrontal cortex is strongly implicated in context-dependent fear modulation, such as fear extinction (Morgan et al., 1999), fear renewal (Knapska et al., 2009; Orsini et al., 2011), remote memories (Frankland et al., 2004), reconsolidation (Stern et al., 2013), contextual learning after hippocampal loss (Zelikowsky et al., 2013) and fear discrimination learning (Lovelace et al., 2014; Vieira et al., 2014; Vieira et al., 2015). The PL subdivision of the mPFC is engaged directly in context-dependent fear acquisition (Zelikowsky et al., 2014), while posttraining mPFC inactivation can trigger inhibition of fear expression during recent and remote contextual fear memory recall (Quinn et al., 2008). More recent studies show that direct optogenetic activation of mPFC neuronal populations triggered by US during fear conditioning leads to elevation of fear in a novel environment when tested 2 or 12 days after conditioning (Kitamura et al., 2017). Based on these data, we hypothesized that the PL network codes functional context-danger associations already during contextual fear conditioning and that these neuronal ensembles of contextual fear memory would be reactivated during consecutive memory retrievals.

To trace neuronal ensembles of contextual fear memories, we employed an activity-dependent genetic labeling system referred to as the TetTag system (Reijmers et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012; Cai et al., 2016). cFos, Zif268 and Arc are immediate-early genes (IEGs) frequently used as neuronal activity markers in various brain areas (Renier et al., 2016). We employed an Arc promoter-driven genetic tagging system, which allowed us to label activated neuronal populations during two separate experiences, referred to as Event 1 and Event 2 (Fig 1A-B). Exposure to a stimulus during Event 1 drove labeling of activated neurons with GFP, while the second exposure to a stimulus (Event 2) drove Arc expression. Thus, single-labeled cells with GFP or Arc represented selectively distinctive populations induced during Event 1 or 2, and double-labeled cells were active during both events. Genetic GFP tagging of activated cells could occur only during a brief 3-day window, when animals were removed from the low-level Dox diet (40 mg/kg) and given regular food chow. To assure that unintentional labeling would not interfere with data interpretation, we designed number of procedures to control for any nonspecific labeling. All behavioral procedures were performed in dedicated behavioral rooms accessible only to the experimenter(s). Week-long habituation prevented any accidental neuronal-activity gene induction. After genetic labeling was completed, animals received a high-level Dox diet (1 g/kg) to suppress expression of new GFP, as reported previously(Cai et al., 2016). Fig 1C shows that expression of GFP in Dox-treated animals was negligible.

We evaluated the formation and stability of neuronal ensembles induced by aversive-context stimuli (CS+) within the IL and PL subdivisions of the mPFC (Fig 1A). In a parallel control experiment, the performance of the animals was tested in exactly the same behavioral paradigm, including exposure to the same context, except that this group of animals was never exposed to any re-enforcer (Fig 1A, noUS group). In addition, we have tested behavioral performance of cfc/CtxtC mice that were treated the same as the cfc/CS+ mice, but these animals were exposed to a novel, neutral context CtxtC (cfc/CtxtC group) during second exposure (Event 2), while the cfc/CS+ mice were exposed to the same dangerous context CS+ during both Event 1 and 2. The cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups showed good performance on fear conditioning training task compared to the noUS group (Fig 1E. Group x US: F(8, 132) = 13.97, P<0.0001; Group: F(4, 132) = 65.47, P<0.0001; US, F(2, 33) = 18.4, P<0.0001). As anticipated, the noUS group showed no fear during the first and second retrievals (Fig 1F). The cfc/CS+ group showed marked levels of fear during exposure (Event 1) and re-exposure (Event 2) to dangerous context CS+ (Fig 1F, Event 1 vs. Event 2: cfc/CS+, P=0.3819). The cfc/CtxtC group showed elevated fear responses during exposure to CS+ on Day 5 (Event 1) and negligible freezing during exposure to novel context CtxtC on Day 6 (Fig 1F, Event 1 vs. Event 2: cfc/CtxtC, P<0.0001). The control group of mice referred as to HC (Home Cage) underwent the same dietary Dox administration but was left in their home cages throughout the entirety of the assay.

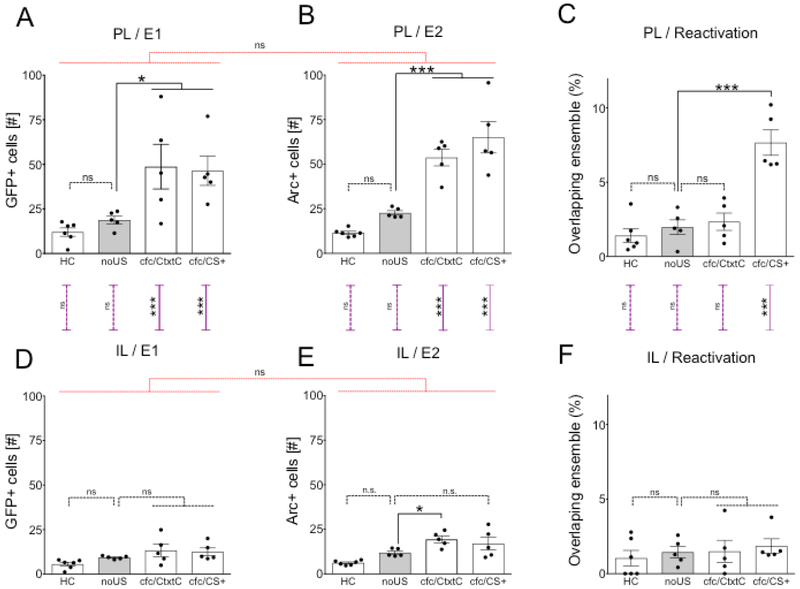

To assess whether the TetTag system was reliable in marking context-danger experiences, we compared levels of reactivation in the mPFC of TetTAG mice that were initially fear-conditioned in context CS+ followed by exposure (Event 1) and re-exposure (Event 2) to the dangerous context CS+ (group cfc/CS+) to levels of reactivation of the noUS group, which underwent the same treatment as the cfc/CS+ group but was never exposed to US (Fig 1A). The activation rates during Event 1 and Event 2 observed in the noUS group were the same as in animals that spent their entire time in their home cages (HC) (Fig 2A: PL/E1: noUS vs HC, P=0.8404. Fig 2B PL/E2: noUS vs HC, P=0.2527. Fig 2D, IL/E1: noUS vs HC, P= 04251. Fig 2E, IL/E2: noUS vs HC, P=1245). We observed increased activity in the PL during both consecutive retrievals of the memory of context-danger associations (Fig 2A: PL/E1: noUS vs. cfc/CS+, P=0.0469; Fig 2B: PL/E2: noUS vs. cfc/CS+, P=0.0001). In addition, the exposure and re-exposure to the aversive context CS+ did not trigger increased activity in IL when those responses were compared to the noUS group (Fig 2D-E). We observed substantial reactivation of PL neuronal ensembles induced by CS+ (predicting US) during re-exposure (Fig 2C: Reactivation in PL, cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P<0.0001), while the same but not-reinforced context failed to trigger reactivation of neuronal ensembles of nonreinforced context memory in PL (Fig 2C: Reactivation in PL, HC vs. noUS, P=0.8398). None of the tested groups showed a reactivation of neuronal ensembles in IL during re-exposure (Fig 2F: one-way ANOVA, F (3, 17) = 0.3895, P=0.7621). Clearly, the reactivation of ensembles associated with context-danger occurred specifically in PL but not in IL. These data indicate that a majority of double-labeled cells (i.e., GFP+ and Arc+) in PL were specific to the context-danger experience.

Figure 2.

Fear conditioning triggers specific neuronal ensemble of contextual stimuli encoding CS+ (cuing US) in the PL. (A) The cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups had greater activation in the PL than the HC group during Event 1. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 17) = 6.757, P=0.0033) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the noUS as a control: noUS vs. HC, P=0.8404; noUS vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.0301; noUS vs. cfc/CS+, P=0.0469. (B) The cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups had greater activation of the PL than noUS group during Event 2. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (ANOVA, F (3, 17) = 28.28, P<0.0001) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the noUS as a control: F (3, 17) = 28.28, P<0.0001: noUS vs. HC P=0.2527, noUS vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.001; noUS vs. cfc/CS+, P=0.0001. (C) The cfc/CS+ group has greater reactivation of PL than cfc/CtxtC, noUS and HC groups. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 17) = 22.52, P<0.0001) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the noUS as a control: noUS vs. HC, P=0.8398; noUS vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.9524; noUS vs. cfc/CS+, P=0.0001;.. (D) During Event 1, there was no difference in activation of IL between groups compared to the noUS group but the cfc/CtxtC group has higher activation than HC in the IL. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 17) = 3.194, P=0.0501) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the noUS as a control: noUS vs. HC, P=0.4251; noUS vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.4115; noUS vs. cfc/CS+, P=0.5672. (E) During Event 2, only the cfc/CtxtC group showed increased activity in the IL compared to the noUS group but the cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups had greater activation than HC. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 17) = 9.221, P=0.0008) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the noUS as a control: noUS vs. HC, P=0.1245; noUS vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.047; noUS vs. cfc/CS+, P=0.2212. (F) There was no difference in reactivation of IL between groups. Ordinary one-way ANOVA: F (3, 17) = 0.3895, P=0.7621. Additional analysis involved comparing data sets across different panels. There was no difference in activation of PL between events (Fig 2A, B). RM two-way ANOVA of Group × Event: Group x Event: F (3, 17) = 1.567, P=0.2339; Event: F (1, 17) = 4.139, P=0.0578; Group: F (3, 17) = 18.03, P<0.0001. There was no difference in activation of IL between events (Fig 2D, E). Group x Event: F (3, 17) = 1.073, P=0.3866; Event: F (1, 17) = 8.438, P=0.0099; Group: F (3, 17) = 8.642, P=0.0010. The cfc/CtxtC, and cfc/CS+ groups show lower activation of IL compared to PL during Event 1 (Fig 2A, D). Ordinary two-way ANOVA (Group × Region: F (3, 34) = 4.204 P=0.0124; Region: F (1, 34) = 31.34, P<0.0001; Group: F (3, 34) = 8.797, P=0.0002) followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons PL/E1 vs. IL/E1: HC, P= 0.8455; noUS, P=0.6506; cfc/CtxtC, P=0.0003; cfc/CS+, P=0.0005. The cfc/CtxtC, and cfc/CS+ groups show lower activation of IL compared to PL during Event 2 (Fig 2B, E). Ordinary two-way ANOVA (Group × Region: F (3, 34) = 15.12, P<0.0001; Region F (1, 34) = 89.6, P<0.0001;Group: F (3, 34) = 35.94, P<0.0001. PL/E2 vs.IL/E2: HC, P= 0.7334; noUS, P=0.1873; cfc/CtxtC, P<0.0001; cfc/CS+, P<0.0001. The cfc/CS+ groups show lower reactivation of IL compared to PL during Event 2 (Fig 2C, F). Ordinary two-way ANOVA Group × Region: F (3, 34) = 10.04, P<0.0001; Region : F (1, 34) = 21.24, Pμ0.0001; Group: F (3, 34) = 15.13, P<0.0001: PL vs. IL: HC, P= 0.9827; noUS, P=0.9514, cfc/CtxtC, P=0.7861; cfc/CS+, P<0.0001 Significance values were set at p < 0.05: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 and ns not significant. Black lines indicate comparisons within a panel; the red lines indicate side-by-side comparisons and purple lines show top-bottom comparisons.

To investigate whether changes in the mPFC neuronal ensemble activation were experience-specific, we compared the performance of the cfc/CS+ groups with the cfc/CtxtC group. The cfc/CtxtC group underwent similar behavioral treatment as cfc/CS+, except that during Event 2, cfc/CS+ mice were exposed to a substantially different context stimulus, CtxtC, while cfc/CS+ animals were re-exposed to the context stimulus, CS+ (Fig 1A). Training data showed that the cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups learned the association between the conditioned stimulus CS+ and US compared to the noUS group (Fig 1E: see above), and both experimental groups showed successful learning at the end of the training. Both cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups showed elevated freezing during Event 1 (Fig 1F: cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P<0.0001; cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, P<0.0001). While re-exposure to context CS+ induced elevated freezing (Fig 1F: Event 2: cfc/CS+ vs. noUS, P=0.0042), exposure to the substantially different, novel CtxtC stimulus (a neutral context) during Event 2 did not trigger fear (Event 2: cfc/CtxtC vs. noUS, P=0.9976).

To evaluate how context specificity affected ensemble reactivation in the mPFC, we compared activity and reactivation in the mPFC of the cfc/CS+ group with the cfc/CtxtC group. Similar to cfc/CS+, the cfc/CtxtC group was also fear-conditioned in context CS+ followed by exposure to CS+ (Event 1), but during Event 2 the cfc/CtxtC group was exposed to the novel context CtxtC. Thus, the cfc/CtxtC group allowed us to test whether two consecutive exposures to two different contextual stimuli would generate overlapping neuronal ensembles in the mPFC during the second exposure. Distinct experiences (i.e., CS+ vs. CtxtC) generated different and nonoverlapping patterns of activity in the PL (Fig 2C: Reactivation/PL: cfc/CtxtC vs. cfc/CS+, P =0.0001). Neither the cfc/CtxtC nor the cfc/CS+ group induced stable ensembles in IL (Fig 2F: Reactivation in IL: one-way ANOVA F (3, 17) = 0.3895, P=0.7621). There was no difference between the cfc/CS+ and cfc/CtxtC groups in activation of PL or IL during exposure to CS+ during Event 1 (Fig 2A: PL/E1: cfc/CS+ vs. CtxtC, P=0.9923; Fig 2D: IL/E1: cfc/CS+ vs. CtxtC, P=0.9885). Induced neuronal activity patterns in the response to the novel context CtxtC during Event 2 were similar to those observed when the CS+ group was tested (Fig 2B: PL/E2: cfc/CS+ vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.2720) suggesting that PL may be engaged during the generation of appropriate responses to both dangerous and novel, discriminated neutral-context stimuli after experience with US but if animals had no prior experience with US (noUS group). The neuronal response to neutral context CtxtC was also detected in IL (Fig 2E: IL/E2 noUS vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.047), but the activity in response to the discriminated Ctxt C was substantially lower in IL compared to PL (Fig 2B, E: Event 2/PL vs IL: two-way ANOVA Group x Region: F (3, 34) = 15.12, P<0.0001; Region: F (1, 34) = 89.6, P<0.0001; Group: F (3, 34) = 35.94, P<0.0001; cfc/CtxtC PL vs IL, P<0.0001). These data provide evidence that the mPFC neuronal ensembles are highly engaged in processing information relevant to context-danger associations and that distinct context-danger related experiences generate different patterns of activity in the mPFC.

In summary, the TetTag system was reliable in marking context-danger experience in the mPFC. As we anticipated, distinct context-danger experiences generated distinctive nonoverlapping patterns of activity in the mPFC. While both the PL and IL circuits can be activated by aversive and neural context stimuli, the PL circuit is more likely to encode lasting memories of context-danger experiences.

3.2. Differential fear conditioning (DC) coincides with generation of neuronal ensembles of context-safety association across subdivisions of the mPFC

The mPFC is involved in fear discrimination learning, but the role of its subdivisions remains unclear (Lovelace et al., 2014; Vieira et al., 2014; Vieira et al., 2015). To test involvement of PL and IL subdivisions of the mPFC in fear discrimination learning, we evaluated PL and IL responses during exposure (Event 1) to dangerous stimulus CS+ and initially non-discriminated, generalized CS− before DC and after (Event 2) (Fig 3A).

To obtain more detailed insight into the prefrontal mechanisms driving fear discrimination learning, we used the TetTag genetic system to label neurons during the early and late phases of fear discrimination learning to evaluate changes in the neuronal ensembles in the PL and IL caused by exposure to three context stimuli during DC: the aversive context stimulus CS+; a similar but not identical, safe stimulus, CS−; and a substantially different safe stimulus, CtxtC (Fig 3A). The HC mice remained in their home cage during the entire behavioral treatment and where not exposed to any of described three context stimuli. Other three groups (dc/CS+, dc/CS− and dc/CtxtC) were exposed to all three contextual stimuli before fear conditioning during habituation (see Methods and Fig 3A). The animals underwent contextual fear conditioning (Day 1-2) followed by the memory retrieval test on Day 3 (CS+ and CS− context testing). Then, the animals were taken off Dox food chow and exposed to one of three contexts (Event 1, Day 6): CS+ (Group dc/CS+), CS− (Group dc/CS−), or CtxtC (Group dc/CtxtC), respectively, followed by a diet switch back to Dox food chow. Genetic tagging of neural ensembles induced by conditioned and generalized fear stimuli during Event 1 (Day 6) was performed when the animals did not discriminate between CS+ and CS−. Following Event 1, these three groups of mice were subjected to 5 days of differential fear conditioning (Days 7-11). On the last day of the behavioral procedure (Event 2, Day 12) each group (i.e., dc/CS+, dc/CS− and dc/CtxtC) was exposed to a specific context stimulus, CS+, CS−, or CtxtC, respectively. Brains were collected 1 hour after the last exposure and were analyzed by histology for Arc gene promoter-dependent patterns of gene expression to evaluate genetically tagged neural ensembles of contextual memories. In the DC paradigm, the context stimulus CS+ was paired with the unconditioned stimulus (US), and the other stimuli, CS− and CtxtC, were not paired with the US. Therefore, CS+ predicted US, and the stimuli CS− and CtxtC predicted the absence of US. While both stimuli CS− and CtxtC predicted safety, CS− initially triggered elevated levels of fear because CS− shared substantial similarities with CS+.

First, we assessed the behavioral performance of the tested animals. During the course of the test, the discrimination between CS+ and CS− steadily increased as animals learned to inhibit generalized fear to the safer stimulus CS−. The third context stimulus CtxtC served as a learning control. CtxtC was substantially different from CS+ and was a good predictor for safety during all phases of testing. All three groups dc/CS+, dc/CS and dc/CtxtC showed robust performance on the differential fear conditioning (Fig 3B. dc/CS+; RM ANOVA: Day F (5, 115) = 16.82 P<0.0001; Context F (1, 23) = 84 P<0.0001, Day x Context F (5, 115) = 7.006 P<0.0001) dc/CS− . Fig 3C. dc/CS−; RM ANOVA: Day F (5, 155) = 15.21, P<0.0001, Context F (1, 31) = 81.3,1 P<0.0001, Day x Context F (5, 155) = 14.47, P<0.0001. Fig 3D. dc/CtxtC; RM ANOVA: Day, F (5, 55) = 4.539 P=0.0016, Context, F (1, 11) = 53.99 P<0.0001, Day x Context, F (5, 55) = 6.024 P=0.0002) after acquisition of conditioned fear responses during Day 1, and there were no differences between groups during fear conditioning (Fig 3E. RM two-way ANOVA Group x US: P= 0.671, US, P <0.0001, Group, P 0.7484). In addition, all three groups dc/CS+, dc/CS and dc/CtxtC showed similar patterns of freezing responses to CS+ and CS−, with elevated responses to CS+ across differential conditioning and descending responses to CS− (freezing to CS−: Fig 3B, dc/CS+, Days 3 vs 11, t(23)=6.97, p<0.0001, r=−0.541; Fig 3C, dc/CS−, t(31)=7.35, p<0.0.0001, r=−0.584; Fig 3D, dc/CtxtC, Days 3 vs 11, t(11)=3.654, p<0.0038, r=−0.450). The dc/CS+, dc/CS− and dc/CtxtC groups showed no difference in performance monitored as a value of Discrimination Index across differential fear conditioning test (Fig 3F. RM ANOVA: Group x Day: P= 0.8098, Day, P <0.0001, Group, P= 0.3177). In addition, all three groups showed similar level of generalization of fear responses to CS− at the beginning of differential fear conditioning (Day 3) and similar level of fear discrimination (CS− vs CS+) after differential fear conditioning (Day 11) (Fig 3G. RM two-way ANOVA Group x Day 3/11: P= 0.0741, Day, P <0.0001, Group, P 0.0871 followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons: Day 3 vs. Day 11: dc/CtxtC, P= 0.0002, dc/CS−, P= <0.0001, dc/CS+, P <0.0001). These data indicate that dc/CS+, dc/CS− and dc/CtxtC groups showed robust performance in fear discrimination learning, and there were no noticeable differences in performance between these groups.

Second, we evaluated changes in the prefrontal circuitry associated with fear discrimination learning. We analyzed neuronal ensembles activated by CS+, CS−, or CtxtC during fear generalization (Day 6), when the animals were unable to distinguish between conditioned and generalized fear stimuli, and we compared these with the neuronal ensembles activated after completion of the fear discrimination learning, when the animals were able to discriminate between the dangerous and safe stimuli (Day 12). To ensure that the activity-labeled neuronal ensembles represented the responses to CS+, CS− and CtxtC stimuli relevant to fear differential conditioning, we analyzed animals in the dc/CS+, dc/CS− and dc/CtxtC groups that showed substantial generalization on Day 3 (Day 3, −0.2<DI<0.2) and appropriate freezing responses to CS+ (above 20% freezing on Day 11). These criteria enabled us to determine the precise context-danger/safety functional relationships by monitoring the activated prefrontal neural ensembles of the context stimuli associated with a full range of fear responses to the tested context stimuli after completion of differential fear conditioning.

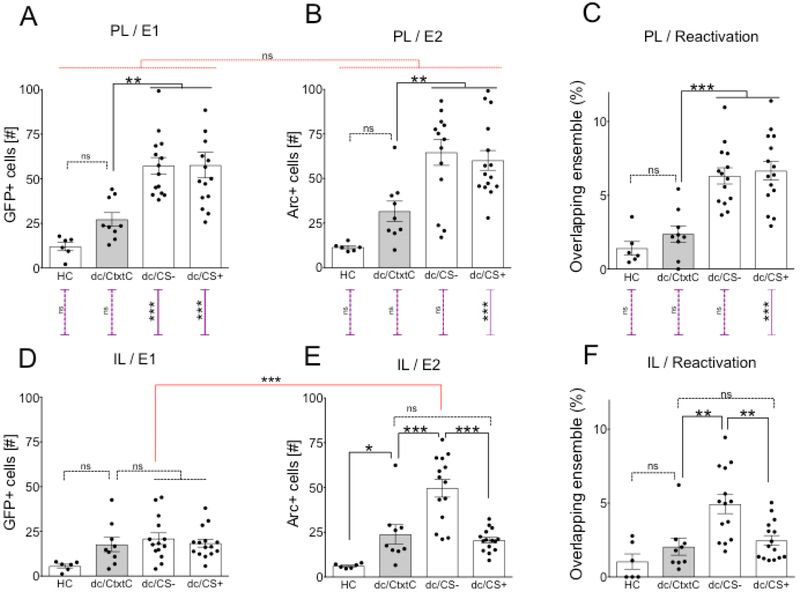

Exposure to the aversive CS+ and the initially generalized CS− context stimuli triggered neural activity in the PL cortex during Event 1 (Fig 4A: Event 1 Activation in PL, ANOVA F(3, 40) = 11.69, P<0.0001; dc/CtxtC vs. HC: P= 0.3445, dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−: P= 0.0029; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+: P= 0.0023). Activation of the PL was also high during re-exposure to both the aversive CS+ and the discriminated, safer context CS− (Fig 4B: Event 2 Activation in PL, ANOVA F(3, 40) = 11.86, P<0.0001; dc/CtxtC vs. HC: P=0.1974, dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−: P=0.0025; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+: P= 0.0086). The levels of response during exposure or re-exposure to CS+ and CS− were not different in PL (Fig 4A-B: PL/E1: cfc/CS+ vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.9999, E2/PL: cfc/CS+ vs. cfc/CtxtC, P=0.8981). In addition, the activation level of PL during Event 2 was not different from Event 1 (Fig 4A-B. PL/E1-E2 RM-ANOVA of Group x Event: Group x Event F (3, 43) = 0.2482 P=0.8622, Event F (1, 43) = 1.216 P=0.2763, Group F (3, 43) = 21.25 P<0.0001). The strong reactivation of the PL neural ensemble was observed during re-exposure to CS+ after differential conditioning (Fig 4C: PL/Reactivation, ANOVA, F (3, 40) = 16.38, P<0.0001 dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.0001), while re-exposure to CtxtC did not trigger the reactivation of the CtxtC ensemble (Fig 4C: dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.6994). There was also strong reactivation in PL in the dc/CS− group (Fig 4C: PL/ Reactivation, dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.0002), indicating that inhibition of generalized fear may be mediated by the PL circuitry. Overall, these results suggest that PL circuitry is involved in discriminatory fear learning; however, the PL tends to detect conditioned and generalized stimuli. Thus, generalized fear is detected in the PL subdivision of the mPFC, and the neuronal ensemble of generalized fear stimuli forms indelible memory representations in the PL during fear discrimination learning.

Figure 4.

Differential fear conditioning triggers elevated IL activity in response to discriminated, safer stimulus CS− and changes in neuronal ensembles of contextual stimuli in PL and IL. The activation analysis of dc/CS+, dc/CS−, dc/CtxtC groups included subjects that generalized before differential conditioning on Day 3 (DI≤0.2) and showed appropriate fear responses to CS+ (Day 11, % Freezing to CS+ > 20%) (Fig 3B-D, F). (A) The dc/CS− and dc/CS+ groups showed similar levels of activity in PL during Event 1 and had greater activation of the PL than the dc/CtxtC group during Event 1, while re-exposure to the CtxtC was not different from the level of activation observed in HC. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 40) = 11.69, P<0.0001) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the dc/CtxtC as a control: dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.3445; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.0029; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.0023.. (B) The dc/CS− and dc/CS+ groups showed similar levels of activity in PL during Event 2 and had greater activation of the PL than the dc/CtxtC group during Event 2, while re-exposure to the CtxtC showed similar levels of activation observed in HC. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 40) = 11.86, P<0.0001) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the dc/CtxtC as a control: dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.1974; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.0025; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.0086.(C) The dc/CS− and dc/CS+ groups showed similar levels of activity in PL and greater reactivation of PL than dc/CtxtC or HC groups. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 40) = 16.38, P<0.0001) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the dc/CtxtC as a control: dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.6994; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.0002; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.0001. (D) The dc/CS− and dc/CS+ groups showed similar activation of the IL as the dc/CtxtC group but had greater activation in IL than HC during Event 1. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 40) = 3.327, P=0.029) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the dc/CtxtC as a control dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.0753; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.7907; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9969. (E) The dc/CS− group showed elevated activation of the IL compared to all other tested groups during Event 2. This increased level of activity in IL of the dc/CS− was also higher compared to responses IL detected during Event 1 (IL/CS−/E1 vs IL/CS−/E2 = <0.0001, details are listed below). Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 40) = 19.27, P<0.0001) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the dc/CtxtC as a control: dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.0439; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.0002; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.8917. (F) The dc/CS− group showed elevated reactivation in the IL compared to all other tested groups. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F (3, 40) = 8.979, P<0.0001) followed by Dunnett's many-to-one comparisons with the dc/CtxtC as a control: dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.5917; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.0016; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9019.

There was no difference in activation of PL between events (Fig 4A, B). RM two-way ANOVA of Group and Event: Group × Event F (3, 43) = 0.2482 P=0.8622; Event F (1, 43) = 1.216 P=0.2763; Group F (3, 43) = 21.25 P<0.0001. There was a marked difference in activation of IL in response to CS− between exposures before and after differential conditioning (Fig 4D, E). Group × Event F (3, 43) = 16.23 P<0.0001; Event F (1, 43) = 30.08 P<0.0001; Group F (3, 43) = 13.19 P<0.0001. Event 1 - Event 2: HC, P>0.9999; dc/CtxtC, P= 0.1045; dc/CS−, P= <0.0001; dc/CS+, P= 0.9139. The dc/CS− and dc/CS+ groups showed lower activation of IL compared to PL during Event 1 (Fig 4A, D). Ordinary two-way ANOVA of Group and Region (Group × Region: F (3, 43) = 10.88 P<0.0001; Region F (1, 43) = 67.78 P<0.0001; Group: F (3, 43) = 12.44 , P<0.0001. PL/El – IL/E1: HC, P= 0.8521; dc/CtxtC, P= 0.3577; dc/CS−, P<0.0001; dc/CS+, P<0.0001. The dc/CS+ group showed lower activation of IL compared to PL during Event 2 (Fig 4B, E). Ordinary two-way ANOVA (Group x Region: F (3, 43) = 7.95 P=0.0003; Region F (1, 43) = 14.89 P=0.0004; Group: F (3, 43) = 21.67 P<0.0001. PL - IL /E2 HC, P= 0.9416; dc/CtxtC, P= 0.9998; dc/CS−, P= 0.5632; dc/CS+, P= <0.0001. The dc/CS+ group showed lower reactivation of IL compared to PL during Event 2 (Fig 4C, F). Ordinary two-way ANOVA Group × Region: F (3, 43) = 6.627 P=0.0009; Region F (1, 43) = 17.41 P=0.0001; Group: F (3, 43) = 22.25 P<0.0001. Reactivation/PL vs. IL: HC, P= 0.9939, dc/CtxtC, P= 0.9415, dc/CS−, P= 0.1571, dc/CS+, P<0.0001. Significance values were set at p < 0.05: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 and ns not significant. Black lines indicate comparisons within a panel; the red lines indicate side-by-side comparisons and purple lines show top-bottom comparisons.

Using the genetic tagging system, we also tracked changes to the activation of the neuronal ensembles in the IL during fear discrimination learning. We found that exposure to safer, discriminated context stimuli triggered elevated neural activity in the IL region during Event 2 (Fig 4E: IL/E2, F (3, 40) = 19.27, P<0.0001; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.0002, r=0.61; dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.0439, dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.8917), but only negligible IL activity in response to non-discriminated, generalized CS− stimulus was recorded during Event 1 compared to CtxtC (Fig 4D: IL/E1, dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.7907, dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.0753; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9969). In addition, inhibition of generalized fear triggered neuronal ensembles of CS− in IL; the dc/CS− group was the only group that showed reactivation of the ensemble in the IL (Fig 4F: IL/Reactivation, one-way ANOVA: F (3, 40) = 8.979, P=0.0001; dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS−, P= 0.0016, r=0.61, dc/CtxtC vs. HC, P= 0.5917, dc/CtxtC vs. dc/CS+, P= 0.9019, dc/CS+ vs. dc/CS−, P=0.0020, r=0.54). Thus, the learned inhibition of generalized fear coincided with an increase of IL activity in as stimuli-specific manner.

The IL responses during exposure and re-exposure to the dangerous context CS+ were markedly lower compared to those detected in the PL (Fig 4A, D:E1/PL - IL, RM-ANOVA Group x Region: F (3, 43) = 10.88, P<0.0001; Region: F (1, 43) = 67.78, P−0.0001; Group: F (3, 43) = 12.44 P<0.0001; E1/PL – IL, dc/CS+, P=0.0001; Fig 4B, E: E2/PL - IL, RM-ANOVA Group x Region: F (3, 43) = 7.95, P=0.0003; Region: F (1, 43) = 14.89, P=0.0004; Group: F (3, 43) = 21.67, P<0.0001; E2/PL – IL, dc/CS+, P<0.0001).

Remarkably, the activation of IL was dramatically increased as a result of successful differential fear conditioning, and this increase was detected in response to CS− only (Fig 4D, E: IL/E1-E2 RM-ANOVA of Group x Event F (3, 43) = 16.23, P<0.0001; Event F (1, 43) = 30.08, Pμ0.0001; Group F (3, 43) = 13.19, P<0.0001; HC, P>0.9999; dc/CtxtC, P= 0.1045; dc/CS−, P= 0.0001; dc/CS+, P= 0.9139). In fact, the level of the IL response during re-exposure to CS− was similar to the PL response (Fig 4E: E2/PL-IL RM-ANOVA Group x Region: F (3, 43) = 7.95, P=0.0003; Region: F (1, 43) = 14.89, P=0.0004; Group: F (3, 43) = 21.67, P<0.0001; HC, P= 0.9416; dc/CtxtC, P= 0.9998; dc/CS−, P= 0.5632; dc/CS+, P<0.0001), while the IL failed to respond to CS+ during Event 2, as mentioned above.

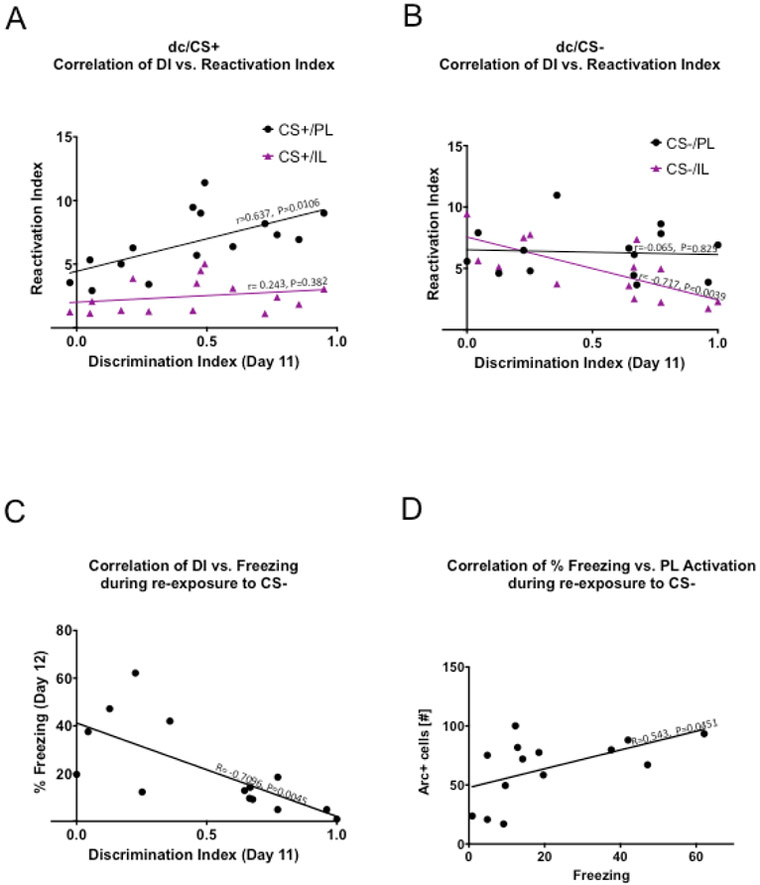

To obtain more insight into the relationships between ensemble activity patterns and differential fear conditioning learning outcome, we performed within-group analyses to evaluate the correlations between the value of a variable representing a measure of neuronal activity (i.e., activity rate or reactivation index in PL vs IL) and the value of behavioral performance (i.e., discrimination index or freezing level) (Fig 6). Simple Pearson correlation analysis was used to evaluate if a stimulus-triggered ensemble reactivation in PL or IL correlated with behavioral performance (Fig 6A-B). Specifically, we wanted to determine which of the ensemble reactivation variables (CS+ or CS−) and which region (PL or IL) correlated with the outcome of differential fear conditioning (i.e., discrimination rate on Day 11). PL ensemble reactivation during re-exposure to CS+ significantly correlated with behavioral performance (CS+/PL, r=0.637, P=0.0106, R2 =0.406). In addition, IL reactivation during re-exposure to CS− showed an inverse relationship with behavioral performance (CS−/IL, r=−0.7175, P=0.0039, R2 =0.515).

Figure 6.

Simple Pearson correlation analysis revealed discrete codes associated with fear discrimination learning. (A) PL ensemble reactivation during re-exposure to CS+ significantly correlated with behavioral performance, (r=0.637, P=0.0106) while there was no correlation between IL ensemble reactivation during re-exposure to CS+ and fear discrimination learning (r= 0.243, P=0.382). (B) In addition, IL reactivation during re-exposure to CS− showed an inverse relationship with behavioral performance, r= −0.717, P=0.0039. PL ensemble reactivation during re-exposure to CS− did not correlate with behavioral performance, r=−0.065, P=0.825. (C) Freezing level variable showed an inverse relationship with outcomes of fear discrimination learning, r= −0.7096, P=0.0045. (D) PL activation rates showed a direct relationship with expressed levels of fear during re-exposure to safer stimulus, CS− (r=0.542, P=0.0451).

One of the features of context-dependent fear discrimination learning is an inhibition of generalized fear to CS−, while preserving elevated responses to CS+ (Fig 3B-D). To assess a potential relationship between region-specific ensemble activity and level of fear, we plotted the activation rate of neuronal ensembles in the PL or IL during exposure or re-exposure to a contextual stimulus (i.e., CS+ or CS−) as a function of fear level (Fig 6). This analysis did not consider directly the discrimination between CS+ and CS− but instead evaluated the relationship between activity and fear level. Pearson correlation analysis revealed that PL activation during re-exposure to CS− was the only variable that was covariate with level of fear (Fig 6D). Surprisingly, PL activation rate during re-exposure to the safer stimulus CS− showed a direct relationship with expressed level of fear during re-exposure to the safer stimulus CS− (r=0.543, P=0.0451), while PL activity in response to CS+ remained stable across levels of freezing (r=−0.295, P=0.286). In addition, detailed analysis of behavior during this test showed that level of fear to the safer stimulus CS− decreased with increasing values of the discrimination index (Fig 6C, r=−0.710, P=0.0045), indicating that animals showing a high level of fear to CS− did not perform well on the differential fear conditioning test. The direct relationship between PL activity rate and level of fear after differential conditioning was detected only during the experience with CS− and not during the experience with CS+. This indicates that PL engagement in mediating responses to safer contexts intensifies with the increase in the probability of failing the discrimination test, while lowered, likely more refined, PL activation occurs when the probability of an appropriate fear response to a safer, discriminated context stimulus (CS−) is high.

The between-group analysis revealed that PL was strongly engaged in responses to CS+ (dangerous) and CS− (initially generalized and later discriminated) before and after differential conditioning. Analysis of the correlation between reactivation indexes in PL during re-exposure to CS+ and CS− and behavioral performance of individual animals revealed additional details of activity patterns associated with performance during fear discrimination learning. The reactivation index for PL ensembles of CS+ and behavioral outcome tended to increase or decrease together, which suggests that improved performance correlates with increased overlapping ensembles, presumably via strengthening functional connectivity within initially activated ensembles of dangerous stimuli in PL. Interestingly, exposure to CS− induced significant PL activity during the early and late phases of differential conditioning, with a significant level of overlap between these ensembles.

Success of differential conditioning also correlated with emerged CS−induced neuronal activity in IL detected during late-phase of differential conditioning, but not before. The initially generalized CS− stimulus triggered negligible activity in IL compared to the never-generalized CtxtC stimulus. However, re-exposure to the discriminated, safer CS− stimulus evoked significant activity in IL compared to CtxtC or the activity during the initial exposure to CS−. This newly emerged IL ensemble of CS− showed marked reactivation, which was specific, as both CS+ and CtxtC failed to show any reactivation. In addition, the IL ensemble of CS− showed lower rates of reactivation with increasing behavioral performance, indicating substantial levels of recruitment of newly activated cells as fear discrimination was learned.

These data suggest that balancing PL and IL networks while encoding more precise information about US-CS+ and noUS-CS− contingencies across subdivisions of the mPFC controls fear discrimination learning. Within-group correlation analysis of the relationships between activity patterns and behavioral performance showed three important correlates of fear discrimination learning outcome: 1) the direct relationship with PL reactivation index during re-exposure to CS+, 2) the inverse relationship with IL reactivation index during re-exposure to CS−, and 3) the inverse relationship between freezing and PL activity during re-exposure to CS−,. In addition, freezing level to the discriminated, safer CS− showed an inverse relationship with outcomes of fear discrimination learning. Furthermore, between-group analysis revealed robust activation and marked reactivation of the CS+ and CS− ensembles in PL and of the CS− ensemble in IL after differential fear conditioning.

4. Discussion

While there is extensive research on the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying fear acquisition and fear extinction, the neural mechanisms driving fear discrimination learning are not well understood. We examined prefrontal neuronal ensembles representing distinct experiences associated with learning to disambiguate between dangerous and similar but not identical, safe stimuli. These data revealed prefrontal subdivision-specific patterns of neuronal reactivation and distinct quantitative reactivation differences in response to neutral, conditioned and generalized contextual fear stimuli, all associated with successful fear discrimination learning. These data support the idea that gating responses to context stimuli within fear modulation circuits appear to be critical to fear inhibition during learning safety cues in ambiguous circumstances.

That the mPFC is a locus for gating fear discrimination and danger assessment is supported by animal studies in which mPFC lesions impair the ability to guide behavior, specifically when memory retrieval resolves conflicting dangerous and safe contextual cues (Dias et al., 1996; Birrell et al., 2000; Ragozzino et al., 2003; Rich et al., 2007). A decline in fear is associated with elevated activity in the mPFC, as determined by the activation of immediate-early genes (Herry et al., 2004; Knapska et al., 2009), blood oxygenation level (Phelps et al., 2004), cell firing (Burgos-Robles et al., 2007) and local field potentials (Lesting et al., 2011). The mPFC has dense reciprocal anatomical and functional connections with the sensory cortices; thalamic sensory relays such as the nucleus reuniens; memory systems, including the hippocampus, which are involved in space, time and multisensory processing; and the amygdala, the critical locus for fear processing. Neurons in the mPFC, basolateral amygdala (BLA) and hippocampus are functionally coupled in the theta range (4-12 Hz oscillations) during fear conditioning (Seidenbecher et al., 2003; Popa et al., 2010), conditioned extinction (Lesting et al., 2011) and discriminative fear learning (Likhtik et al., 2014).

There is a large body of evidence demonstrating that the PL encodes and holds information about specific context-danger associations. Our data demonstrate that fear conditioning triggers neuronal ensembles of the context-danger association (Fig 2-3). While blocking the PL cortex before fear conditioning has no effect on cued or contextual fear memory retrieval, posttraining PL inactivation during the cued or contextual fear memory recall decreases the expression of learned fear (Corcoran et al., 2007). In fact, learned fear expression and extinction failure are correlated with sustained conditioned responses in PL neurons (Burgos-Robles et al., 2009). Moreover, the patterns of IEG gene expression confirm that the mPFC network monitors context-danger associations during fear conditioning (Kitamura et al., 2017) and neural ensembles of contextual fear memory were found in the PL cortex during fear retrieval (Zelikowsky et al., 2013; Zelikowsky et al., 2014). In addition, context-dependent fear memory retrieval after extinction, referred to as memory renewal, depends on the PL cortex (Maren et al., 2004; Orsini et al., 2011; Maren et al., 2013; Jin et al., 2015b, a). Upregulation of the immediately early gene c-fos in the PL correlates with fear renewal (Knapska et al., 2009), providing more evidence that PL tracks the context-danger association.

Our data provide evidence for engagement of PL networks in mediating learning of fear discrimination. Fig 3B-D demonstrates that fear discrimination learning involves lowering fear responses to CS− while maintaining a high level of response to CS+. The PL network is directly engaged during brain responses to CS− before and after differential fear learning (Fig 4). Moreover, we detected substantial reactivation of CS− neuronal ensembles in PL, suggesting that fear discrimination learning might coincide with encoding memories of a discriminated, safer context into the PL networks. Other findings are in line with this assessment, as general disengagement of PL networks due to treatment with muscimol blocked recall of discriminated fear (Lee et al., 2012). This impairment was specific to responses to CS− only (Lee et al., 2012) emphasizing the importance of PL network integrity for the learning of appropriate responses to initially generalized stimuli during differential conditioning. Others reported that electrolytic lesions of PL administered after discrimination learning, presumably destroying already formed ensembles of contextual memory, were ineffective in disrupting context fear discrimination (Kim et al., 2013). While PL neural ensembles of contextual memory may not always be critical for fear discrimination recall, these ensembles may provide advantages when the prefrontal-hippocampal memory system requires flexibility under more complex conditions, such as those observed during fear memory renewal (Maren et al., 2004; Orsini et al., 2011; Maren et al., 2013; Jin et al., 2015b, a) (Knapska et al., 2009).

The observed PL reactivation coinciding with learning context-safety contingencies is surprising considering previous research on fear extinction. In fact, it is widely believed that the IL but not PL circuitry mediates learning underlying fear inhibition. Milad and Quirk demonstrated that the CS−evoked responses in the IL coincide with learned fear suppression (Milad et al., 2002). This was later reproduced in several studies (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2006; Quirk et al., 2008; Sierra-Mercado et al., 2010; Sotres-Bayon et al., 2010; Courtin et al., 2013). Research over the last 16 years has revealed that the modulation of fear responses associated with fear extinction learning comprises the formation of a new memory trace that can actively suppress fear expression (Bouton, 2002; Myers et al., 2006). The current model of fear extinction learning predicts that CS would induce required IL activation during successful recall of fear extinction learning, followed by sending instructions to suppress fear by tapping into the fear circuit via monosynaptic IL→GABAergic intercalated amygdala neurons (ITC) (Likhtik et al., 2008;Pinard et al., 2012) or, as more recently described, di-synaptic IL→BLA→ITC pathways (Royer et al., 1999; Royer et al., 2002; Strobel et al., 2015). In addition, direct optogenetic silencing of IL neurons impairs retrieval of auditory fear extinction only when neuronal inhibition is triggered during extinction training but not during the retrieval of extinction memory (Do-Monte et al., 2015). Thus, IL may be mediating fear extinction learning but is dispensable for extinction memory retrieval. Moreover, both IL and PL have shown elevated firing rates during extinction recall (Holmes et al., 2012), and both PL→BLA and IL→BLA connections show synaptic plasticity during extinction recall (Cho et al., 2013). The PL but not IL cortex has been implicated in guiding context-appropriate behavior in responding to conflicting information in rats (Marquis et al., 2007). In addition, PL inactivation disrupts the encoding and expression of conditioned fear under the task circumstance that animals have to use contextual cues to disambiguate the significance of the stimuli (Sharpe et al., 2014). Thus, encoding specific memories across larger PL and IL networks as reported in this study might be critical for proper gating of context-danger and context-safety contingencies during top-down control of appropriate fear responses.

While there is evidence that the PL is engaged in mediating responses to CS− and CS+, it is unclear if the PL component of ensembles representing inhibited fear is required for appropriate responses to discriminated, safer stimuli after differential fear conditioning. Our data show that generalized, non-discriminated stimuli triggered CS− ensemble activity in PL but not in IL networks before differential conditioning (Fig 4A, D). Conversely, CS+ ensembles are localized in the PL through fear discrimination learning, and their reactivation rate within PL correlates with successful expression of discriminated fear. Notably, there was a direct relationship between the total number of cells activated in PL during Event 2 and expression of fear responses to the discriminated, safer CS−stimulus. The ratio of the subset of cells activated by the safer stimulus CS− before and after differential conditioning to the total number of cells activated during re-exposure to context CS− appears to be stable across different levels of discrimination index, but the total number of activated cells in response to discriminated, safer stimuli decreases as animals lower their generalized fear. Taken together, these data suggest that PL might be involved in mediating inhibition of generalized fear via refinement of a subpopulation of CS−responsive cells. Unfortunately, we are not able to test this hypothesis due to technological limitations of the TetTag system.

Re-exposure to a discriminated and safer context after differential conditioning induced a modified CS− ensemble, now present in both PL and IL (Fig 4B, E). Conditioned and generalized stimuli triggered only negligible responses in IL, while discriminated, safer stimuli elicited stimulus-specific activity in IL. Interestingly, IL reactivation rates during re-exposure to CS−showed an inverse relationship with performance in fear discrimination learning, suggesting recruitment of new neurons to IL ensembles of CS− as a result of fear discrimination learning.Similar behavior of CS− ensembles during fear discrimination learning has been observed in the lateral amygdala (Grosso et al., 2018). Thus, the engagement of IL in mediating responses to safer stimuli in addition to PL and the lateral amygdala is a result differential fear conditioning. One feasible interpretation is that PL and IL are both involved in balancing an enlarged CS−ensemble spreading across the entire mPFC while learning appropriate responses to discriminated safer stimuli. This interpretations of our data is consistent with recently published work demonstrating that PL projections to IL are directly involved in initial but not late learning of fear extinction (Marek et al., 2018). Thus, it is conceivable that PL projections to IL provide pathways for information transfer and/or circuit expansion between PL and IL during learning of fear inhibition to conditioned or generalized stimuli. If these predictions are correct, the enlarged IL-PL ensemble of discriminated, safer CS− stimuli would emerge as an expansion of the CS−ensemble detected initially only in PL during generalization. Our findings are consistent with a potential role of PL→IL communications in the generation of new IL ensembles of CS− during differential conditioning. Thus, increased reactivation of the CS+ ensemble in the PL and reorganization of CS− ensemble across IL subdivision of the mPFC are both hallmarks of fear discrimination learning.

In summary, both the IL and PL are engaged during differential fear conditioning, yielding inhibition of generalized fear, while fear conditioning triggers stable memory representations of the conditioned stimulus in the PL subdivision of the mPFC. Initial experiences with undifferentiated conditioned (CS+) and generalized (CS−) stimuli during early differential fear conditioning elicit neuronal population activity distributed across PL but not in IL. Surprisingly, the PL activity rate of CS− ensembles increased with the triggered level of fear, suggesting that inhibition of generalized fear may involve lowering the number of CS− specific cells in PL. In addition, CS+ ensemble reactivation index showed a direct correlation with performance in fear discrimination. It appeared that IL cortices were recruited during the late phase of differential fear conditioning, which coincided with successful fear discrimination. Compression of CS− ensembles in PL coincided with enlargement of CS− ensembles in IL during fear discrimination learning. In fact, the CS− reactivation rate in IL during re-exposure to the discriminated, safer stimulus CS− was one of the best predictors of fear discrimination learning outcome. These data demonstrate that learning safety signals involves large network changes across both PL and IL subdivisions of the mPFC.

4. Conclusions

This research illuminates the network-wide changes in the mPFC associated with learning to inhibit generalized fear. Evidence from context-dependent fear discrimination learning tasks indicated substantial changes in population activity patterns within distinct subdivisions of the mPFC during fear discrimination learning. Both the PL and IL subdivisions of the mPFC mediate fear discrimination learning, while fear conditioning induces changes in the mPFC circuitry that are limited to the PL subdivision. Our findings suggest that differential fear conditioning involves encoding new memory representations within both PL and IL, which is consistent with our hypothesis that fear discrimination is largely a process by which initially generalized fear memories are sharpened by selective diminution of the fear, driving the response to nonreinforced stimuli, perhaps through interactions between the amygdala, hippocampal system, and mPFC during the consolidation of selective memories.

Highlights:

Differential fear conditioning sparks neuronal ensembles associated with the inhibition of generalized fear in both the prelimbic and infralimbic cortices.

Differential fear conditioning increases neuronal activation to the safer stimulus in IL.

Ascending reactivation rates of dangerous stimulus-evoked populations in the prelimbic cortex and descending reactivation rates of safer stimulus-triggered population in the infralimbic cortex are both correlated with fear discrimination learning outcome.