Abstract

Therapeutic strategies based on in vitro transcribed mRNA (IVT) are attractive because they avoid the permanent signature of genomic integration that is associated with DNA-based therapy, and result in the transient production of proteins of interest. To date IVT has mainly been used in vaccination protocols to generate immune responses to foreign antigens. In this “proof-of-principle” study we explore a strategy of combinatorial IVT to recruit and reprogram immune effector cells to acquire divergent biological functions in mice in vivo. First, we demonstrate that synthetic mRNA encoding CCL3 is able to recruit murine monocytes in a non-programmed state, exhibiting neither bactericidal nor tissue-repairing properties. However, upon addition of either Ifn-γ mRNA or Il-4 mRNA we successfully polarized these cells to adopt either M1 or M2 macrophage activation phenotypes. This cellular reprogramming was demonstrated through increased expression of known surface markers and through the differential modulation of NADPH oxidase activity, or the superoxide burst. Our study demonstrates how IVT strategies can be combined to recruit and reprogram immune effector cells that have the capacity to fulfill complex biological tasks in vivo.

Introduction

Synthetic mRNA therapy has been gaining interest in recent years, thanks to recent advances in enhanced stability and a reduction in inflammatory response (1–9). Because of its non-replicative nature, synthetic mRNA acts simply as a transient carrier of information that will be degraded via metabolic pathways within a few days (2, 10). Therefore, synthetic mRNA poses minimal risk of genomic insertional mutagenesis, an obvious concern for DNA-based therapy (1, 2, 10, 11). Moreover, synthetic mRNA therapy does not require nuclear delivery for transcription, unlike DNA-based therapy (1, 2, 10, 11). Finally, synthetic mRNA can maintain protein expression at a controllable level for several days (2, 10), which compares favorably with recombinant protein that is delivered as a bolus with relatively short-lived half-life (12, 13). Lastly, recent data indicate that appropriate chemical modification of synthetic mRNA can provide a localized and intense expression of desired proteins in selected tissues or organs (1, 2, 13).

Preclinical studies using synthetic mRNA have been conducted in various fields including cancer immunotherapy (14–17), infectious disease vaccine delivery (18–20), immune-inflammatory diseases (21, 22) and protein-replacement therapy (23, 24). Clinical trials involved HIV vaccine design (25, 26), and treatment of cancers such as prostate cancer (27, 28), pancreatic cancer (29), colon cancer (30), melanoma (30) and acute myeloid leukemia (31, 32). These studies emphasize the expression of proteins that can recognize and eliminate malignant targets (virus, microbe or cancer cells) (16, 17, 23, 24, 28), or pathogen-derived proteins that trigger antigen-specific immune recognition (14, 15, 18, 19, 27, 29, 30).

One area of application for synthetic mRNA that we feel has been under-exploited is in the controlled expression of immuno-modulatory proteins capable of recruiting and reprogramming immune effector cells to fulfill specific functions at defined body sites. In this study, we developed a “proof-of-principle” strategy to recruit and modulate host immune cells in vivo using synthetic mRNA encoding chemokines known for their ability to recruit monocytes, memory T cells, neutrophils and natural killer (NK) cells (33–37). We found that circulating monocytes recruited by synthetic mRNA encoding CCL3 retained a non-programmed state, without adopting either a bactericidal or tissue-repairing phenotype. Most significantly however, the addition of synthetic mRNA encoding either IFN-γ or IL-4 selectively drove the recruited monocytes to divergent polarization states. Synthetic mRNA for Ifn-γ activated the recruited monocytes and resident macrophages into the adoption of an anti-microbial state. In contrast, the addition of Il-4 mRNA drove the cells towards expression of markers of alternative activation, or wound-healing behavior. The data provide a new perspective into how synthetic mRNA may be used for localized delivery to both recruit and reprogram immune effector cells with the capacity to adopt polar opposite behaviors to either increase microbial killing, or to enhance localized tissue repair.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6J mice, CD45.1+ mice (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and housed under pathogen-free conditions. All experiments were approved by Cornell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tissue Culture cells

Hela cells, Vero cells and J774 cells were purchased from ATCC. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated from hematopoietic stem cells isolated from CD45.1+ or CD45.2+ mice bone marrow, and maintained in DMEM (Corning Cellgro) containing 10% FBS (Thermo Scientific), 10% L929-cell conditioned media (containing M-CSF), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin) (Corning cellgro), at 37C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After 6-day culture, cells were either split for further expansion or frozen with FBS containing 10% DMSO in liquid nitrogen for later use (38).

IVT mRNA synthesis and transfection

IVT mRNAs encoding for mouse CCL2 (NCBI: NM_011333), CCL3 (NCBI: NM_011337), IFN-γ (NCBI: NM_008337.4), and IL-4 (NCBI: NM_021283.2) were synthesized from template plasmids (Life Technologies) containing a T7 promoter followed by a Kozak consensus sequence, the gene sequence of interest, and the mouse alpha globin 3’ untranslated region. A NotI restriction site was inserted following the 3’ UTR sequence, and plasmids were linearized overnight. The digested DNA template was purified and used for in vitro mRNA transcription (Cellscript). A 2’-O-methyl cap-1 structure and poly(A) tail were added enzymatically using the manufacturer’s instructions, which increases their stability and expression efficiency. mRNAs were synthesized with a complete substitution of uridine to N-1-methyl pseudouridine (Trilink), which has been shown to increase protein expression and decrease innate immune activation (5). mRNA was treated with Antartic phosphatase (New England Biolabs) for 30 minutes to remove residual triphosphates before a final RNA purification step using a RNeasy midi kit (Qiagen). Finally, all mRNAs were quantified on a Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific) and stored frozen at –80°C.

For delivery of synthetic mRNA 5X105 J774 or Vero cells seeded in 24 well plate, or 2X106 BMDMs (freshly cultured or thawed from frozen stocks) seeded in 6 well plate were transfected with mRNA using Viromer Red transfection reagent following manufacture’s procedure. Briefly, 2μg mRNA/1X106 cells were diluted in transfection buffer and incubated with Viromer Red particle for 20min before added to the cells. At indicated time points, the supernatant was collected for ELISA. J774 or Vero cells were fixed for immunofluorescence. In all experiments involving i.p. injection of cells, BMDMs (1X106 cells/mouse) were scraped and washed before injection to animals intraperitoneally. For direct injection of naked mRNA to animals, mRNAs were diluted in transfection buffer and incubated with or without Viromer Red particles for 20min before injection to the animals.

Optimization of chemically mRNA modification

mRNAs with modification of 5-methylcytidine (5meC), pseudouridine (Y), N1-methyl-pseudouridine (m1Y), 5-methoxycytidine (5moC), 5-methoxyuridine (5moU) and combinations between these modifications were synthesized by Trilink.

1X105 Hela cells were plated in 24 well plates the day prior to transfection with 200 ng of mRNA and 1μl of Lipofectamine 2000 per well in duplicate wells per construct and time point. At 12 hours post transfection, cells were harvested and GFP expression was detected by flow cytometry and luciferase by Promega luciferase assay systems. For stress granule formation assays, the same transfection conditions were used; cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with Triton-X, and stained for G3BP (BD Biosciences, 61126), a known stress granule marker. qPCR was performed using qPCR primers (Qiagen) for IFN-β and IL-6, with and without the addition of C16 (Sigma, 2μM) or 2AP (Sigma, 10 mM), both of which are PKR inhibitors.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were plated onto #1.5 glass coverslips the day before use. At the indicated time points, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min before permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature (Sigma). Cells were then blocked in 10% Donkey Serum and 5% BSA for 30 min at 37 °C before incubation with primary anti-GFP antibody (8 μg/ml, Life Technologies, a11122) for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 30 min at 37 °C. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Life Technologies) for 5 min and mounted onto glass slides with Prolong gold.

Collection of peritoneal exudate cells and peritoneal fluid

To collect peritoneal exudate cells and peritoneal fluid, sacrificed mice were injected with 10ml of cold PBS+5%FBS intraperitoneally without pulling out the syringe. The abdomen of the animals was massaged a few times before withdrawing liquid. The withdrawn fluid was centrifuged at 1000G to separate the peritoneal exudate cells and the peritoneal fluid.

ELISA

5×105 J774 or Vero cells were plated into each well of a 24 well plate. After incubating overnight, cells were transfected with either 1μg of CCL2 or CCL3 mRNA or were incubated with 10 μg/ml LPS or control media for 24 h. Cell supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 104 G for 10 min to clear the supernatant. Supernatants or peritoneal fluid from different mice were diluted and tested by ELISA kits for mouse CCL2 (R&D, MJE00), CCL3 (R&D, MMA00), IFN-γ (R&D, MIF00) and IL-4 (R&D, M4000B).

Isolation of monocytes from bone marrow of CD45.1+ mice and adoptive transfer

Procedure followed the instruction of monocyte isolation kit from Mitenyi Biotec (130–100-629). Briefly, bone marrow from two CD45.1+ mice was isolated from femur and tibias. These bone marrow cells were labeled with magnetic beads and passed through a LS column. The monocytes were enriched in the unlabeled cells and injected to CD45.2+ mice (1X106 cells/mouse) through retro-orbital.

Flow cytometry

For surface staining, cells were washed with PBS and blocked with PBS plus 5% FBS, 2.5% mouse serum and 0.5% anti Fcγ III/II (anti-CD16/32) for 15min. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with viability dye (1:500, eBioscience) and antibodies (1:200) for 15 min. Cells were washed with PBS and analyzed by LSR II (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometric data were further analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

For intracellular staining, cells were incubated with Brefeldin A (1:1000, eBioscience) in RPMI media plus 10% FBS in 37 C for 4–5h. Then cells were washed, blocked and stained according to the Intracellular Staining protocol (eBioscience). Cells were washed with PBS and analyzed by BD LSR II.

Antibodies used in this paper include Ly6C-APC Cy7, Ly6C-APC, F4/80-PE, F4/80-e450, Ly6G 1A8-PE Cy7, Ly6G 1A8-FITC (BD), CD45.2-APC, CD45.2-AF700, CD45.1-PE, CD45.1-AF700, CD3-e450, NK1.1-AF780, CD11b-PerCP Cy5.5 (BD), CD206-PE, Arginase1-PE (R & D), Anti-mouse Relm-α antibody (PeproTech). Antibodies were from eBioscience unless stated otherwise.

Detecting intracellular superoxide burst by Oxyburst assay

Preparation of Oxyburst reporter beads is described previously (39). For the 96 well plate assay, 10μl suspension of beads (a bead-to-cell ratio of 2:1) was added to each well and the plate was agitated immediately to distribute the beads. The plate was transferred to a plate reader (Perkin-Elmer) and analyzed for 2h. For flow cytometry, 100μl suspension of beads (a bead-to-cell ratio of 2:1) was added to each 6 well and the plate was agitated immediately. At indicated time points, the cells were washed, fixed by 4% PFA and stained for analysis by flow cytometry.

Statistics

Two-tailed Unpaired Student t test with Welch-correction and One-way ANOVA with Turkey multiple comparison tests were conducted in Prism (GraphPad). All experiments were repeated at least twice. Number of mice used in each experiment is indicated in figures.

Results

Expression of CCL2 and CCL3 in vitro using synthetic mRNA.

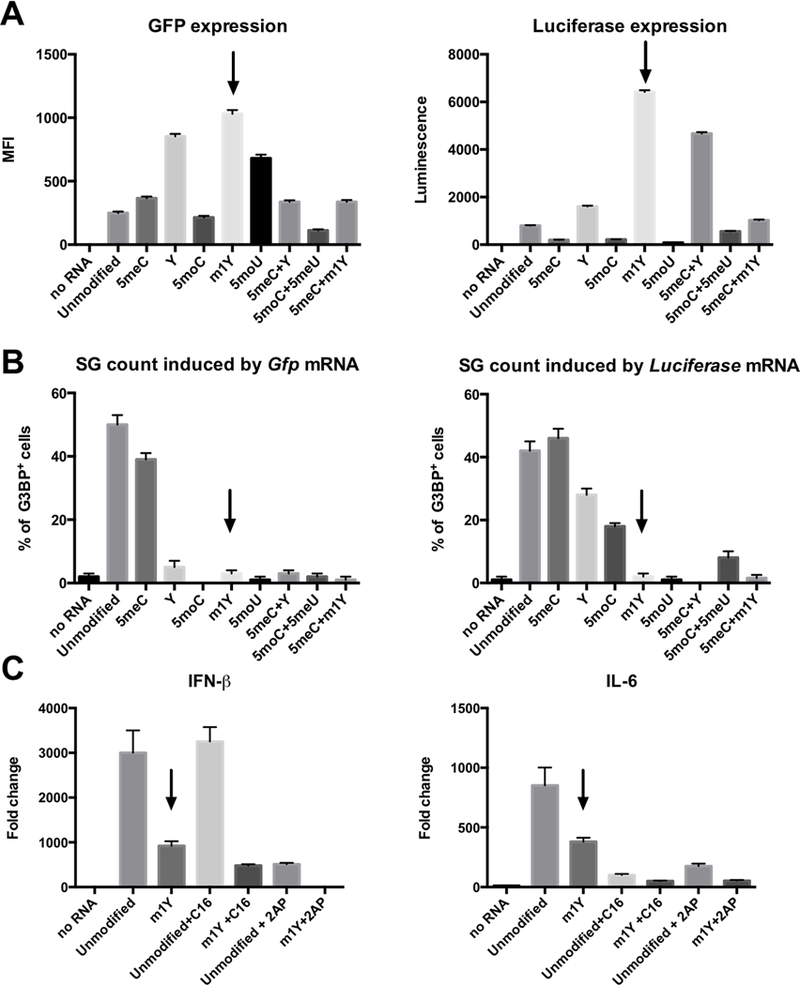

Prior to initiating macrophage transfection experiments we used permissive Hela cells to explore different modifications of our synthetic mRNAs to optimize expression and stability, and to minimize their cellular activation properties. mRNAs were synthesized with chemical modifications including 5’ capping, alteration of 5’ and 3’ UTRs, coding region optimization, and 3’ poly(A) tail elongation (detailed procedures are included in Methods and Materials). Previous studies had shown that mRNA synthesized with substitution of uridine with N-1-methyl pseudouridine increases protein expression and reduces innate immune activation (5, 6). We tested the impact of a variety of naturally-occurred mRNA modifications on protein expression and immune activation, including 5-methylcytidine (5meC), pseudouridine (Y), N1-methyl-pseudouridine (m1Y), 5-methoxycytidine (5moC), 5-methoxyuridine (5moU) using mRNAs encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) and luciferase as readouts. We found that mRNA with modification of m1Y yielded the highest GFP and luciferase production (Fig 1A) while the percentage of transfected cells were similar across all chemical modifications. Moreover, we assessed the degree of immune activation of different mRNA modifications by detecting stress granule (SG) formation. We observed significantly lower SG production with m1Y modification for mRNAs encoding GFP and luciferase (Fig 1B), indicating that mRNAs with m1Y modification minimizes perturbation of the target cells. The reduced activation shown by the m1Y modification was also reflected in reduced production of IFN-β and IL-6 transcripts (Fig 1C). We found that PKR inhibitors (2AP and C16) can further reduce the production of IFN-β and IL-6 transcripts (Fig 1C) however, the reduction was minimal and not considered biologically significant. In all subsequent experiments we synthesized our mRNAs with the N-1-methyl pseudouridine (m1Y) substitution.

Figure 1. mRNA with N1-methyl pseudouridine substitution induces high protein expression levels with limited target cell activation.

We explored different chemical modifications of synthetic mRNA in Hela cells to assess both efficiency of expression and minimization of target cell activation. A: Expression of GFP and Luciferase by mRNAs with different chemical modifications (5meC, Y, 5moC, m1Y, 5moU and combinations of these modifications) in Hela cells. B: Percentage of G3BP+ Hela cells (contain stress granules) following transfection with mRNAs with different modifications. C: Expression of IFN-β and IL-6 in Hela cells when transfected with Gfp mRNAs with different modifications as demonstration of immune activation.

Upon delivery of synthetic mRNA encoding GFP to Hela cells we observed GFP expression as early as 5h post-transfection. The GFP signal peaked between 8h and 24h post-transfection, and lasted for 72 hours (Supplemental Fig 1A). Interestingly, we found that macrophages, traditionally thought of as resistant to transfection, were very effective at expressing foreign genes when delivered in the form of synthetic mRNA. The murine macrophage-like cell line, J774, was transfected with Gfp mRNA and approximately 70% of the cells expressed GFP protein 24 hours post-transfection (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. J774 cells transfected with synthetic mRNA encoding GFP, CCL2 or CCL3, respectively.

We examined the expression of synthetic mRNAs encoding GFP, CCL2, and CCL3 in the murine macrophage-like cell line J774. A: Cells were transfected with 1μg of Gfp mRNA and fixed 24 hours post-transfection. Cells were stained for GFP (green) and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 12μm. B: CCL2 and CCL3 were detected by ELISA in in tissue culture supernatants following transfection of cells with either 1μg of Ccl2 or Ccl3 mRNA (blue) or following incubation with 10μg/mL LPS for 24 h. Scale bars represent standard deviation. Data represents mean of two independent experiments. Statistical significance was measured by two-way ANOVA. *: p<0.05. **: p<0.01. ***: p<0.001. ****: p<0.0001.

To explore the potential for manipulating tissue responses we decided to focus on mRNAs encoding chemokines known to stimulate recruitment of immune effector cells (33–37). CCL2 (MCP1) and CCL3 (MIP1α) recruit different immune cells including monocyte, memory T cell, neutrophil and natural killer (NK) cell. We transfected the J774 cells with Ccl2 or Ccl3 synthetic mRNAs and verified the presence of CCL2 or CCL3 in the medium by ELISA 24h post-transfection (Fig. 2B). Although both mRNAs were expressed, we focused primarily on Ccl3 synthetic mRNA due to its more sustained expression (Fig. 2B).

Monocyte recruitment by CCL3 expressed from synthetic mRNA.

To demonstrate that CCL3 expressed from synthetic mRNAs was functionally-active and could be generated in sufficient amounts to modify cell behavior we developed an experimental cell recruitment assay. We transfected murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) with Ccl3 mRNA and injected these cells into the peritoneal cavity of mice (Fig. 3A). We used congenic CD45.1 and CD45.2 mice pairs to discriminate between the Ccl3 mRNA-transfected BMDMs and the recipient mouse cells present in the peritoneum (Supplemental Fig. 1B). We reasoned that the peritoneal cavity was a suitable site for ease of sampling for subsequent analysis of both cell recruitment and cellular phenotype. BMDMs from CD45.1+ mice were transfected with Ccl3 mRNA using Viromer Red (VR) particles and cultured for 8h prior to inoculation into the peritoneum. Peritoneal exudate cells and fluid were collected 16h post-inoculation with the Ccl3 mRNA transfected BMDMs. The presence of CCL3 protein was confirmed in both the tissue culture medium from the transfected BMDMs prior to their inoculation, as well as in peritoneal fluid from mice injected with the transfected BMDMs (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Ccl3 synthetic mRNA transfected BMDM modify the cellular populations in the peritoneal cavity.

We examined the biological impact of introducing BMDMs transfected with synthetic mRNA encoding CCL3 into the peritoneal cavity of mice. A: Experiment setup. In brief, we transfected synthetic mRNAs encoding either CCL2 or CCL3 into bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) generated from CD45.1+ congenic mice. As control, we transfected BMDM with VR without mRNA. 8h after transfection, the cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and injected intraperitoneally into CD45.2+ congenic mice. 16h later, we collected the cells from the peritoneal cavity and analyzed them by flow cytometry. The use of the congenic CD45.1+/CD45.2+ mouse strains enabled us to discriminate between the donor BMDM transfected with the chemokine mRNAs and the resident tissue macrophages. B: Demonstration of the presence of CCL3 protein in the supernatant from BMDMS transfected with Ccl3 mRNA, as well as in the peritoneal fluid from mice inoculated with these BMDMs. C: Ccl3 synthetic mRNA transfected BMDM recruited a population of Ly6ChiCD11b+ monocytes (Gate 1), increased the number of Ly6CintCD11b+ monocytes (Gate 2), and decreased the number of F4/80hi large peritoneal macrophages. Experiments were repeated 3 times. Data showed representative flow plot from one experiment. D: The numbers of Ly6Chi and Ly6CintCD11b+ monocytes, F4/80hi large peritoneal macrophage and Ly6G+ neutrophil were quantified. E: As an additional control to demonstrate the recruitment phenotype was due to CCL3-encoding mRNA we compared the levels of cellular recruitment to VR alone, VR coated with Gfp mRNA and VR coated with Ccl3 mRNA. The recruitment of the cell population of significance, the Ly6Cint CD11b+ monocytes was clearly specific to the presence of the Ccl3 mRNA. Data represent mean ± SD. ns: p>0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, Unpaired t test with Wench correction.

The majority of phagocytes in an unperturbed peritoneal cavity are resident peritoneal macrophages that express high levels of F4/80 (Supplemental Fig. 2B). In contrast, in the mice receiving transfected BMDMs expressing CCL3, we observed an increase in monocytes expressing high or intermediate levels of Ly6C and low levels of F4/80 (Fig. 3C, 3D, Supplemental Fig. 2A, B). This suggested that these monocyte populations were distinct from F4/80-high, resident peritoneal macrophages. Interestingly, the number of F4/80high peritoneal macrophages and their F4/80 expression were markedly decreased in these mice (Fig. 3C, 3D, mental Fig. 2C). This apparent “disappearance” of resident peritoneal macrophages has been reported previously upon inflammation induced by intraperitoneal inoculation of thioglycollate broth, LPS or bacteria (40–42). The total number of peritoneal exudate cells, the F4/80lowLy6ClowMHCII+ peritoneal macrophages and Ly6Clow monocytes recovered from the peritoneal cavity were similar between the mice receiving Ccl3 mRNA-transfected BMDMs and mice in the control groups (Supplemental Fig. 2D). Moreover, the numbers of donor cells recovered 16h post injection are similar between groups and were mostly dead (Supplemental Fig. 2D). To demonstrate that the recruitment was specific to CCL3-encoding mRNA we inoculated the peritoneal cavities of mice with BMDMs transfected with uncoated VR particles, VR particles coated with Gfp mRNA and VR particles coated with Ccl3 mRNA. While we did observe modest cellular recruitment to VR alone and Gfp mRNA coated VR, consistent with minimal immune activation, there was a substantial increase in the Ly6Cint monocyte population that was specific to the Ccl3 mRNA (Figure 3E). This indicates that cellular recruitment phenomenon is a function specific to the CCL3-encoding mRNA.

Previous studies reported that intraperitoneal (IP) injection of recombinant CCL3 (rCCL3) triggers recruitment of neutrophils, detectable at 2h and peaking at 8h post-inoculation (21). Injection of rCCL3 into an air pouch animal model also drove monocyte recruitment (22). To examine the differences between the delivery of a bolus of recombinant CCL3 protein, versus the sustained localized expression from Ccl3 mRNA we compared the activities of rCCL3 and BMDM transfected with Ccl3 mRNA in the peritoneal cavity at 4h and 16h (Supplementary Fig. 2E, F). As previously reported, rCCL3 injection recruited neutrophils at 4h and 16h. In comparison, injection of Ccl3 mRNA transfected BMDMs did result in neutrophil recruitment at 4h but not at 16h (Supplemental Fig. 2E, F). In contrast, rCCL3 did not recruit monocytes either at 4h or 16h, while synthetic Ccl3 mRNA transfected BMDMs exhibited marked monocyte recruitment at both time point (Supplemental Fig. 2E, F). The data indicate that there are both quantitative and qualitative differences between delivery of a single dose of recombinant protein versus the sustained local expression of the chemokine CCL3.

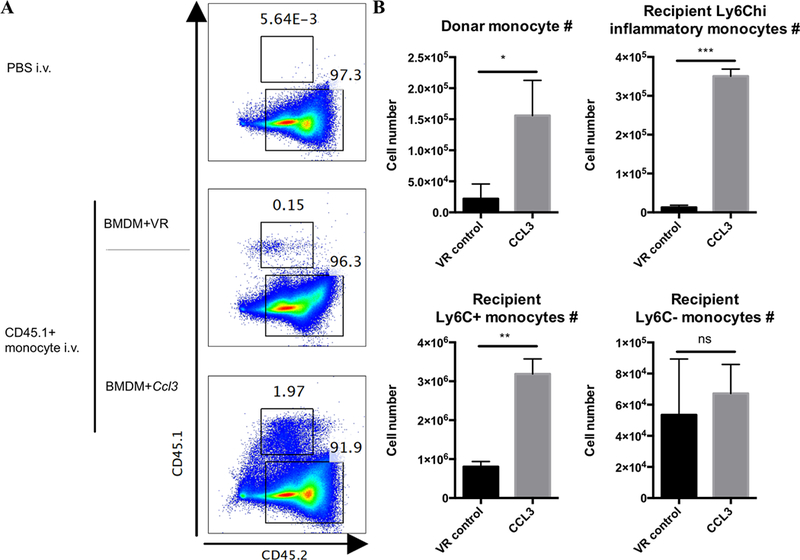

Monocytes are recruited through blood stream to the peritoneal cavity in a non-activated State.

Upon acute inflammation or pathogen infection, monocytes are recruited via the blood stream to peripheral tissues, in response to various inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as CCL3 (36, 43, 44). To verify that the increased Ly6C+ monocyte populations in the peritoneal cavity were indeed recruited from the blood stream, we isolated monocytes from CD45.1+ mice and injected them intravenously to CD45.2+ mice that were subsequently inoculated with BMDM transfected with Viromer Red particles with or without Ccl3 mRNA. We observed an increase in CD45.1+ cells in the peritoneum of mice injected with Ccl3 transfected BMDMs demonstrating that these cells came from the peripheral blood (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Peripheral blood-derived monocytes are recruited to the peritoneal cavity.

We demonstrate that the cells recruited into the peritoneal cavity in response to CCL3 had their origin in the blood. A: Representative flow plots showing mice in which peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from CD45.1+ mice and transferred intravenously (1X106 monocytes transferred per mouse) to CD45.2+ mice. These CD45.2+ mice were injected intraperitoneally with BMDMs transfected with or without Ccl3 mRNA and the presence of recruited CD45.1+ monocytes in the peritoneal cavity was assessed. Experiments were repeated 2 times. B: The number of donor CD45.1+ monocytes, Ly6Chi, Ly6Cint and Ly6Clow monocytes were quantified. Data represent mean ± SD. ns: p>0.05, *: p < 0.05, ***: p < 0.001, Unpaired t test with Wench correction.

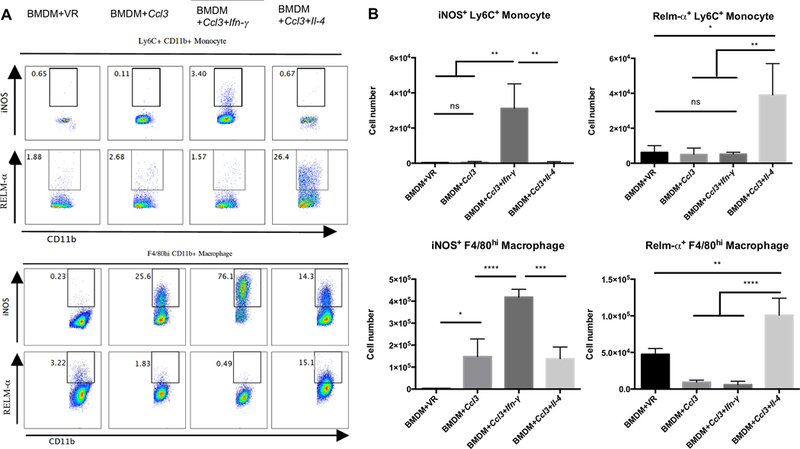

In acute inflammatory challenge models, such as thioglycollate broth injection, monocytes are recruited by a complex mix of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that both recruit cells and drive them into an inflammatory, or M1 activation state (36, 45–49). We therefore wanted to determine the activation state of the monocytes recruited by BMDM transfected with synthetic Ccl3 mRNA. We examined the expression levels of iNOS and RELM-α proteins to determine whether the recruited monocytes had acquired either a classically-activated (M1) or alternatively-activated (M2) phenotype. Intriguingly, we found that very few monocytes recruited through CCL3 activity expressed either iNOS or RELM-α (Fig. 5A, B, upper panels). The data indicate that, in the absence of additional stimuli, the recruited monocytes adopted neither bactericidal nor tissue-repairing phenotypes, but remained “unprogrammed”. This result suggests that CCL3 is responsible for immune cell recruitment, but without additional signals, it is not involved in the activation or polarization of the recruited cells. We also examined the levels of surface expression of MHCII, CD80 and CD86 on recruited monocytes, as well as resident macrophages and neutrophils. Again, the ectopic expression of Ccl3 mRNA in donor BMDMs did not increase the expression of these markers on the cell types examined, with the exception of a marginal increase in CD80 expression on recruited monocytes (Supplemental Fig. 3).

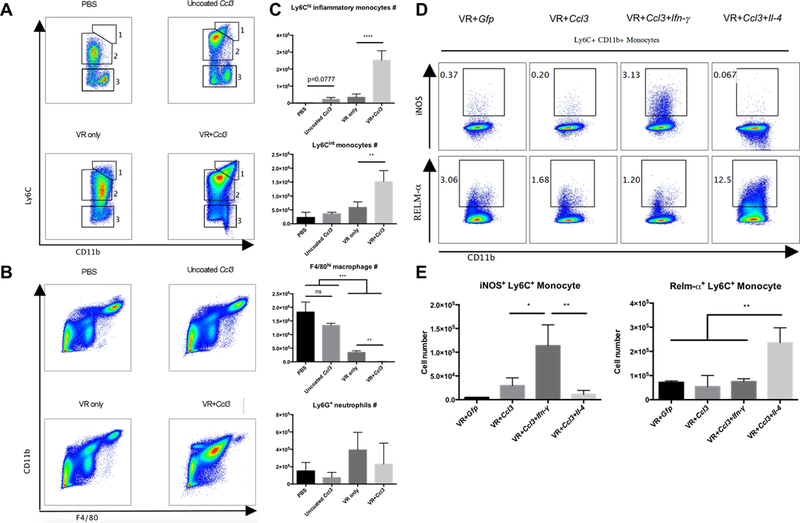

Figure 5. Co-transfection of Ifn-γ or Il-4 synthetic mRNA, in combination with Ccl3 mRNA, reprograms both resident and recruited cell phenotypes.

In order to demonstrate that the recruited cells can be polarized towards M1- and M2-like macrophage phenotypes we co-transfected BMDMs with cytokine-encoding mRNAs. A: Representative flow plots showing the expression of iNOS and RELM-α in recruited monocytes (Ly6C+CD11b+, upper panel) and in large peritoneal macrophages (F4/80hiCD11b+, lower panel) following their induction of Ccl3 mRNA in combination with Ifn-γ or Il-4 mRNA. B: The numbers of iNOS+ or RELM-α+ recruited monocytes and F4/80hi macrophages were quantified and shown to increase in the presence of appropriate cytokine-encoding mRNAs Experiments were repeated three times with comparable results. Data represent mean ± SD. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Recruited Monocytes can be Re-Programmed by Co-Expression of Additional Synthetic mRNAs.

We next asked if it were feasible to specifically drive these non-activated monocytes towards M1 and M2 states of activation. We designed and synthesized two synthetic mRNAs that encoded Ifn-γ and Il-4 transcripts, respectively. The expression of the mRNAs was validated through the detection of IFN-γ and IL-4 in the supernatant following their transfection into Vero cells (Supplemental Fig. 4A). The Ifn-γ or Il-4 mRNAs were mixed with the Ccl3 mRNA and transfected into CD45.1+ BMDM, and then injected into CD45.2+ mice peritoneum. IFN-γ and IL-4 expression was detected in the peritoneal fluid (Supplemental Fig. 4B). Moreover, Ifn-γ mRNA transfected CD45.1+ BMDMs recovered from the peritoneum were actively expressing IFN-γ (Supplemental Fig. 4C). Phenotypic characterization of the peritoneal exudate cells revealed a marked increase in the number of iNOS-positive monocytes recruited in response to synthetic mRNAs encoding Ccl3 and Ifn-γ (approximately 30-fold above the controls) (Fig. 5A, B, upper panels). We also observed a similar increase in the number of RELM-α positive monocytes recruited by the Ccl3 and Il-4 mRNA combination (approximately 20-fold above the controls), (Fig. 5A, B, upper panels). RELM-α is an accepted marker for M2 polarization of macrophages (50, 51).

Unsurprisingly, the expression of IFN-γ and IL-4 by the BMDMs inoculated into the peritoneum also affected the resident macrophage population (F4/80highCD11b+), which adopted M1 or M2 phenotypes, respectively. The iNOS-positive resident macrophages increased by approximately 50 fold in response to the BMDMs transfected with synthetic Ccl3 and Ifn-γ mRNAs (Fig. 5A, B, lower panels), while the number of RELM-α positive resident macrophages increased by approximately 40 fold in response to Ccl3 and Il-4 mRNA-transfected BMDMs (Fig. 5A, B, lower panels).

Further characterization of the peritoneal exudate cells demonstrated that the resident macrophages and recruited monocytes from mice receiving BMDMs transfected with Ccl3 and Ifn-γ mRNA also up-regulated MHC II expression (Supplemental Fig. 3). Surface expression of CD80 was increased in recruited monocytes, but not in resident macrophages or neutrophils (Supplemental Fig. 3). Ccl3 and Il-4 mRNA had little effect on the expression of the panel of surface markers that we utilized for cell typing (Supplemental Fig. 3).

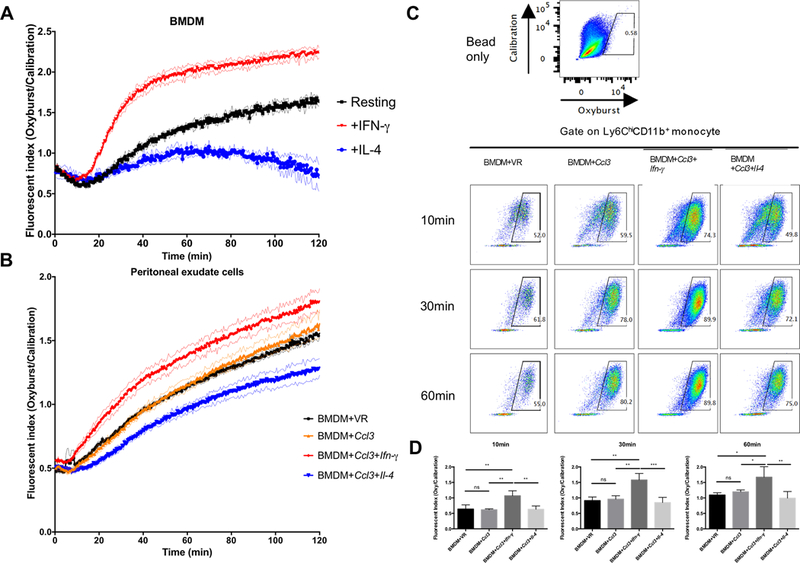

Functional demonstration of phagocyte activation.

To provide a functional assessment of the polarization state of the phagocytes we quantified the magnitude of the superoxide burst, which had been shown previously to be amplified in IFN-γ-activated macrophages (39). Carboxy-methylated silica beads were covalently modified with BSA-Oxyburst-SE and a calibration fluorochrome to quantify phagosomal NADPH oxidase activity. We confirmed the utility of the assay by demonstrating that treatment of BMDM with recombinant IFN-γ led to increased production of reactive oxygen species, while exposure to recombinant IL-4 reduced oxygen radical production in BMDM (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Quantification of NADPH Oxidase activity in the reprogrammed phagocytes correlates with the M1 or M2 activation status.

To generate functional data demonstrating the polarization of the recruited macrophages we quantified the intensity of their superoxide burst. A: The kinetics and magnitude of superoxide burst generated by BMDMs treated with or without recombinant IFN-γ and IL-4. Activation with IFN-γ enhanced the superoxide burst (Oxyburst beads), while alternative activation with IL-4 resulted in its decrease. Analysis was performed on a Perkin Elmer Envision fluorescent plate reader and the experiment was repeated three times. B: The kinetics and magnitude of superoxide burst generated by peritoneal cells from mice (n=3) injected with BMDMs transfected with mRNAs encoding CCL3 alone and in combination with either Ifn-γ and Il-4 mRNAs. The experiment was repeated twice. C: Peritoneal cells from mice (n=3) injected with different mRNA transfected BMDMs were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative flow plots showing the gating of positive Oxyburst signal. Oxyburst beads without cells served as the negative control (upper panel). The lower panels were gated on recruited monocytes (Ly6C+CD11b+) from 4 groups incubated with Oxyburst beads and harvested at different times (10min, 30min and 60min). The experiment was repeated three times. D: Quantification of fluorescent index of mean Oxyburst bead fluorescent intensity. The mean Oxyburst fluorescent intensity of all the recruited monocytes that were positive for calibration fluor were calculated. The number was divided by the mean calibration fluorescent intensity to generate a fluorescent index. The experiment was repeated three times with comparable results. Data represent mean ± SD. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

We harvested the peritoneal exudate cells from the mice injected with BMDM transfected with synthetic mRNA, plated the cells in 96 well plates, and added the Oxyburst reporter beads. Peritoneal exudate cells from mice injected with Ccl3 transfected BMDM showed levels of reactive oxygen production comparable to those from control mice. However, the peritoneal exudate cells from mice injected with Ccl3 and Ifn-γ mRNA transfected BMDM exhibited increased production of oxygen radicals, whereas the peritoneal exudate cells from mice injected with Ccl3 and Il-4 mRNA transfected BMDM exhibited reduced reactive oxygen production (Fig. 6B).

To further validate this phenotype at the level of the individual cells we incubated the peritoneal exudate cells with Oxyburst reporter beads in 96 well plates. At indicated time points, cells were fixed and analyzed by flow cytometry. We found that recruited monocytes from mice injected with Ccl3 and Ifn-γ mRNA transfected BMDM showed elevated levels of reactive oxygen species as early as 10 min after addition of reporter beads (Fig 6C&D). This elevated level of superoxide burst in the recruited monocytes from mice injected with Ccl3 and Ifn-γ mRNA transfected BMDM was sustained throughout the duration of the experiment (Fig 6C&D).

The data confirm that while CCL3 alone recruits monocytes in a relatively non-activated state, co-expression of other synthetic mRNAs can be exploited to reprogram the cells to adopt specific physiologically states associated with either microbicidal activity or wound healing.

Naked mRNA complexed with Viromer Red particles induces comparable monocyte recruitment.

In our initial experiments we deliberately utilized ex vivo transfection of BMDMs so we could effectively control and track the source of chemokines and cytokines, and discriminate between the effector and responder cell populations. However, to have therapeutic potential we need to demonstrate that direct delivery of synthetic mRNA to a body site induces a comparable response. In these experiments we inoculated PBS, uncoated Viromer Red (VR) particles, naked Ccl3 mRNA, VR particles coated for Gfp mRNA, and VR particles coated with Ccl3 mRNA, directly into the peritoneum. Of the GFP-positive cells recovered from the peritoneal cavity at time of analysis, 62% of these cells were F4/80hi, or resident peritoneal macrophages (Supplemental Fig. 4D). The inoculation of PBS, uncoated VR particles, and naked Ccl3 mRNA all failed to induce significant recruitment of the Ly6Chi or Ly6Cint monocytes (Fig. 7A-C). In contrast, intraperitoneal injection of Ccl3 mRNA-coated VR induced recruitment of Ly6hi and Ly6int monocytes to levels comparable to those observed with transfected BMDM (Fig. 7A-C). Furthermore, inoculation of VR particles coated with Gfp-encoding mRNA or Ccl3 mRNA had minimal impact on phagocyte polarization, while the inoculation of VR particles coated with Ccl3 plus Ifn-γ mRNA, or with Ccl3 and Il-4 mRNA induced marked up-regulation of expression of the polarization markers iNOS (Ifn-γ) and RELM-α (Il-4). Synthetic mRNA, delivered complexed to VR particles, induced phenotypes comparable to those observed following inoculation of ex vivo transfected BMDMs. These data validate the general approach and demonstrate the utility of synthetic mRNA to induce localized and controlled modulation of immune environments in vivo.

Figure 7. mRNA complexed with Viromer Red particles can recruit similar populations of monocytes and differentiate them towards different activation statues.

The potential of this approach for therapeutic applications is supported by the demonstration that the mRNA-coated VR particles can mediate comparable effects following direct inoculation. A: Representative flow plots of monocyte populations in the peritoneal cavity after injection of naked, Ccl3 mRNA or Ccl3 mRNA-coated Viromer Red particles. B: Representative flow plots of F4/80hi large peritoneal macrophage in the peritoneal cavity after injection of naked, Ccl3 mRNA or Ccl3 mRNA-coated Viromer Red particles. C: Quantification of the numbers of Ly6Chi and Ly6Cint monocytes, F4/80hi large peritoneal macrophage and Ly6G+ neutrophil. D: Representative flow plots of iNOS and RELM-α expression in these monocytes recruited by Viromer Red complexed mRNAs. E: Quantification of iNOS+ and RELM-α+ number of monocyte recruited by Viromer Red complexed mRNAs. Experiment was repeated two times. Data represent mean ± SD. ns: p>0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Discussion

Synthetic mRNA therapy is a promising therapeutic approach to deliver proteins of interest (1, 2, 10, 11). It has low risk of genomic insertional mutagenesis sometimes associated with DNA-based therapy and bypasses the necessity of nuclear delivery for expression (1, 2, 10, 11). Compared to recombinant protein therapy, synthetic mRNA can potentially maintain expression of a desired protein at physiological levels for an extended time period time period, which has the potential to reduce the frequency of administration (2, 10). Moreover, mRNA transfected cells can actively migrate to targeted tissues or organs to provide the localized release of desired proteins (1, 2, 13). Synthetic mRNA therapy has already been explored in several preclinical and clinical studies predominantly to express proteins with direct therapeutic effect or proteins to trigger an antigen-specific immune response (2, 12, 13).

In this study, we examined the potential for using synthetic mRNA in cell-based therapies to recruit effector cells and modify their behavior locally in vivo. Our findings demonstrated that Ccl3 synthetic mRNA transfected BMDMs were able to recruit monocytes to the peritoneal cavity. Instead of being polarized to either a bactericidal or a tissue-repairing phenotype, the recruited monocytes remained in a relatively naïve state through the migration process. Once recruited, the monocytes were responsive to both the addition of Ifn-γ mRNA and driven into a M1, anti-microbial state, or to Il-4 mRNA to adopt an M2, tissue repair phenotype. These data demonstrate how synthetic mRNAs could be used in combination to expand and diversify the biological functions of both transfected and bystander cells.

Chemokines, such as CCL3, are reported to recruit neutrophils as well as monocytes (35, 52–55), however, much of these data were generated in pro-inflammatory models. In the current study, while we did observe transient recruitment of neutrophils, the monocytes that were recruited appeared to be predominantly in a “resting” or non-activated state. Synthetic mRNAs have the potential to activate mammalian cells through Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRR) such as TLR 7/8, RIG-1 and NOD2, discussed by Steinle and colleagues (56). However, the modifications introduced into the synthetic mRNA used in the current study appear to minimize cellular activation. Previous work by Andries et al., 2015, showed that N-1-methyl pseudouridine modification increased luciferase expression and decreased IFN-β and CCL5 in A549 cells. We also found that N-1-methyl pseudouridine, in combination with other modifications, minimized host cell activation, assessed by stress granule formation (a result of PKR activation) and reduced production of IFN-β and IL-6. Evidence that the single stranded synthetic mRNAs themselves play a minimal role in the phenotype of the recruited and resident phagocytes is provided by the absence of activation markers in mice receiving BMDMs transfected with Ccl3 mRNA (Supplemental Fig. 3), and in mice that received Viromer Red particles complexed with Ccl3 mRNA (Fig. 7). The absence of an in vivo pro-inflammatory response to the mRNA itself is important if one envisions utilizing this as a strategy for recruitment of immune effector cells capable of subsequent re-programing.

The ability to recruit specific cell types that can subsequently be re-programmed represents an important new concept in the field of in vitro transcribed mRNA-based therapy (IVT). In vaccination strategies one could include synthetic mRNAs encoding cytokines to recruit professional antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, together with the foreign antigen mRNA to enhance the efficiency of antigen presentation and the robustness of the immune response. One could envision new antimicrobials based on expression of chemokines for recruitment in combination with activating cytokines, such as IFN-γ, or specific anti-microbial proteins such as cathelicidin. Macrophages and monocytes are ideal target cells for such strategies because they are known to respond to well-characterized recruitment signals. Moreover, they are extremely plastic and can be reprogrammed to fulfill a broad range of beneficial activities that include killing foreign microbes, or tumor cells, tissue remodeling and repair, and anti-fibrotic functions. They are an ideal target for combinatorial IVT strategies and we believe that this “proof-of-principle” study opens new avenues for future therapies that could further expand the potential applications of this rapidly evolving field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

The authors would like to thank Linda Bennett for her support throughout the course of this project.

This work was supported by DARPA funding to PJS, XS, and DGR. DGR is supported by National Institutes of Health awards AI134183 and AI1185820.

References

- 1.Kuhn AN, Beibetaert T, Simon P, Vallazza B, Buck J, Davies BP, Tureci O, and Sahin U. 2012. mRNA as a versatile tool for exogenous protein expression. Curr Gene Ther 12: 347–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahin U, Kariko K, and Tureci O. 2014. mRNA-based therapeutics--developing a new class of drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 13: 759–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kormann MS, Hasenpusch G, Aneja MK, Nica G, Flemmer AW, Herber-Jonat S, Huppmann M, Mays LE, Illenyi M, Schams A, Griese M, Bittmann I, Handgretinger R, Hartl D, Rosenecker J, and Rudolph C. 2011. Expression of therapeutic proteins after delivery of chemically modified mRNA in mice. Nat Biotechnol 29: 154–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson BR, Muramatsu H, Jha BK, Silverman RH, Weissman D, and Kariko K. 2011. Nucleoside modifications in RNA limit activation of 2’−5’-oligoadenylate synthetase and increase resistance to cleavage by RNase L. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 9329–9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andries O, Mc Cafferty S, De Smedt SC, Weiss R, Sanders NN, and Kitada T. 2015. N(1)-methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. J Control Release 217: 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svitkin YV, Cheng YM, Chakraborty T, Presnyak V, John M, and Sonenberg N. 2017. N1-methyl-pseudouridine in mRNA enhances translation through eIF2alpha-dependent and independent mechanisms by increasing ribosome density. Nucleic Acids Res 45: 6023–6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kariko K, Muramatsu H, Welsh FA, Ludwig J, Kato H, Akira S, and Weissman D. 2008. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol Ther 16: 1833–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kariko K, Muramatsu H, Ludwig J, and Weissman D. 2011. Generating the optimal mRNA for therapy: HPLC purification eliminates immune activation and improves translation of nucleoside-modified, protein-encoding mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 39: e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, and Weissman D. 2005. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 23: 165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlake T, Thess A, Fotin-Mleczek M, and Kallen KJ. 2012. Developing mRNA-vaccine technologies. RNA Biol 9: 1319–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirschman JL, Bhosle S, Vanover D, Blanchard EL, Loomis KH, Zurla C, Murray K, Lam BC, and Santangelo PJ. 2017. Characterizing exogenous mRNA delivery, trafficking, cytoplasmic release and RNA-protein correlations at the level of single cells. Nucleic Acids Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadas Y, Katz MG, Bridges CR, and Zangi L. 2017. Modified mRNA as a therapeutic tool to induce cardiac regeneration in ischemic heart disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chien KR, Zangi L, and Lui KO. 2014. Synthetic chemically modified mRNA (modRNA): toward a new technology platform for cardiovascular biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5: a014035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou WZ, Hoon DS, Huang SK, Fujii S, Hashimoto K, Morishita R, and Kaneda Y. 1999. RNA melanoma vaccine: induction of antitumor immunity by human glycoprotein 100 mRNA immunization. Hum Gene Ther 10: 2719–2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fotin-Mleczek M, Duchardt KM, Lorenz C, Pfeiffer R, Ojkic-Zrna S, Probst J, and Kallen KJ. 2011. Messenger RNA-based vaccines with dual activity induce balanced TLR-7 dependent adaptive immune responses and provide antitumor activity. J Immunother 34: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon SH, Lee JM, Cho HI, Kim EK, Kim HS, Park MY, and Kim TG. 2009. Adoptive immunotherapy using human peripheral blood lymphocytes transferred with RNA encoding Her-2/neu-specific chimeric immune receptor in ovarian cancer xenograft model. Cancer Gene Ther 16: 489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett DM, Zhao Y, Liu X, Jiang S, Carpenito C, Kalos M, Carroll RG, June CH, and Grupp SA. 2011. Treatment of advanced leukemia in mice with mRNA engineered T cells. Hum Gene Ther 22: 1575–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinon F, Krishnan S, Lenzen G, Magne R, Gomard E, Guillet JG, Levy JP, and Meulien P. 1993. Induction of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo by liposome-entrapped mRNA. Eur J Immunol 23: 1719–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenzi JC, Trombone AP, Rocha CD, Almeida LP, Lousada RL, Malardo T, Fontoura IC, Rossetti RA, Gembre AF, Silva AM, Silva CL, and Coelho-Castelo AA. 2010. Intranasal vaccination with messenger RNA as a new approach in gene therapy: use against tuberculosis. BMC Biotechnol 10: 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardi N, Secreto AJ, Shan X, Debonera F, Glover J, Yi Y, Muramatsu H, Ni H, Mui BL, Tam YK, Shaheen F, Collman RG, Kariko K, Danet-Desnoyers GA, Madden TD, Hope MJ, and Weissman D. 2017. Administration of nucleoside-modified mRNA encoding broadly neutralizing antibody protects humanized mice from HIV-1 challenge. Nat Commun 8: 14630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramos CD, Canetti C, Souto JT, Silva JS, Hogaboam CM, Ferreira SH, and Cunha FQ. 2005. MIP-1alpha[CCL3] acting on the CCR1 receptor mediates neutrophil migration in immune inflammation via sequential release of TNF-alpha and LTB4. J Leukoc Biol 78: 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouma G, Nikolic T, Coppens JM, van Helden-Meeuwsen CG, Leenen PJ, Drexhage HA, Sozzani S, and Versnel MA. 2005. NOD mice have a severely impaired ability to recruit leukocytes into sites of inflammation. Eur J Immunol 35: 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creusot RJ, Chang P, Healey DG, Tcherepanova IY, Nicolette CA, and Fathman CG. 2010. A short pulse of IL-4 delivered by DCs electroporated with modified mRNA can both prevent and treat autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Mol Ther 18: 2112–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mays LE, Ammon-Treiber S, Mothes B, Alkhaled M, Rottenberger J, Muller-Hermelink ES, Grimm M, Mezger M, Beer-Hammer S, von Stebut E, Rieber N, Nurnberg B, Schwab M, Handgretinger R, Idzko M, Hartl D, and Kormann MS. 2013. Modified Foxp3 mRNA protects against asthma through an IL-10-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest 123: 1216–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allard SD, De Keersmaecker B, de Goede AL, Verschuren EJ, Koetsveld J, Reedijk ML, Wylock C, De Bel AV, Vandeloo J, Pistoor F, Heirman C, Beyer WE, Eilers PH, Corthals J, Padmos I, Thielemans K, Osterhaus AD, Lacor P, van der Ende ME, Aerts JL, van Baalen CA, and Gruters RA. 2012. A phase I/IIa immunotherapy trial of HIV-1-infected patients with Tat, Rev and Nef expressing dendritic cells followed by treatment interruption. Clin Immunol 142: 252–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Gulck E, Vlieghe E, Vekemans M, Van Tendeloo VF, Van De Velde A, Smits E, Anguille S, Cools N, Goossens H, Mertens L, De Haes W, Wong J, Florence E, Vanham G, and Berneman ZN. 2012. mRNA-based dendritic cell vaccination induces potent antiviral T-cell responses in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 26: F1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heiser A, Coleman D, Dannull J, Yancey D, Maurice MA, Lallas CD, Dahm P, Niedzwiecki D, Gilboa E, and Vieweg J. 2002. Autologous dendritic cells transfected with prostate-specific antigen RNA stimulate CTL responses against metastatic prostate tumors. J Clin Invest 109: 409–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su Z, Dannull J, Yang BK, Dahm P, Coleman D, Yancey D, Sichi S, Niedzwiecki D, Boczkowski D, Gilboa E, and Vieweg J. 2005. Telomerase mRNA-transfected dendritic cells stimulate antigen-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. J Immunol 174: 3798–3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morse MA, Nair SK, Boczkowski D, Tyler D, Hurwitz HI, Proia A, Clay TM, Schlom J, Gilboa E, and Lyerly HK. 2002. The feasibility and safety of immunotherapy with dendritic cells loaded with CEA mRNA following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and resection of pancreatic cancer. Int J Gastrointest Cancer 32: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morse MA, Nair SK, Mosca PJ, Hobeika AC, Clay TM, Deng Y, Boczkowski D, Proia A, Neidzwiecki D, Clavien PA, Hurwitz HI, Schlom J, Gilboa E, and Lyerly HK. 2003. Immunotherapy with autologous, human dendritic cells transfected with carcinoembryonic antigen mRNA. Cancer Invest 21: 341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anguille S, Van de Velde AL, Smits EL, Van Tendeloo VF, Juliusson G, Cools N, Nijs G, Stein B, Lion E, Van Driessche A, Vandenbosch I, Verlinden A, Gadisseur AP, Schroyens WA, Muylle L, Vermeulen K, Maes MB, Deiteren K, Malfait R, Gostick E, Lammens M, Couttenye MM, Jorens P, Goossens H, Price DA, Ladell K, Oka Y, Fujiki F, Oji Y, Sugiyama H, and Berneman ZN. 2017. Dendritic cell vaccination as postremission treatment to prevent or delay relapse in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 130: 1713–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Tendeloo VF, Van de Velde A, Van Driessche A, Cools N, Anguille S, Ladell K, Gostick E, Vermeulen K, Pieters K, Nijs G, Stein B, Smits EL, Schroyens WA, Gadisseur AP, Vrelust I, Jorens PG, Goossens H, de Vries IJ, Price DA, Oji Y, Oka Y, Sugiyama H, and Berneman ZN. 2010. Induction of complete and molecular remissions in acute myeloid leukemia by Wilms’ tumor 1 antigen-targeted dendritic cell vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 13824–13829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshimura T 2017. The production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)/CCL2 in tumor microenvironments. Cytokine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshimura T, Robinson EA, Tanaka S, Appella E, Kuratsu J, and Leonard EJ. 1989. Purification and amino acid analysis of two human glioma-derived monocyte chemoattractants. J Exp Med 169: 1449–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maurer M, and von Stebut E. 2004. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36: 1882–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi C, and Pamer EG. 2011. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 762–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolpe SD, Davatelis G, Sherry B, Beutler B, Hesse DG, Nguyen HT, Moldawer LL, Nathan CF, Lowry SF, and Cerami A. 1988. Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokinetic properties. J Exp Med 167: 570–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fink A, Hassan MA, Okan NA, Sheffer M, Camejo A, Saeij JP, and Kasper DL. 2016. Early Interactions of Murine Macrophages with Francisella tularensis Map to Mouse Chromosome 19. MBio 7: e02243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.VanderVen BC, Yates RM, and Russell DG. 2009. Intraphagosomal measurement of the magnitude and duration of the oxidative burst. Traffic 10: 372–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barth MW, Hendrzak JA, Melnicoff MJ, and Morahan PS. 1995. Review of the macrophage disappearance reaction. J Leukoc Biol 57: 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shannon BT, and Love SH. 1980. Additional evidence for the role of hyaluronic acid in the macrophage disappearance reaction. Immunol Commun 9: 735–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomazic V, Bigazzi PE, and Rose NR. 1977. The macrophage disappearance reaction (mdr) as an in vivo test of delayed hypersensitivity in mice. Immunol Commun 6: 49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, and Pamer EG. 2008. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annu Rev Immunol 26: 421–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiong H, and Pamer EG. 2015. Monocytes and infection: modulator, messenger and effector. Immunobiology 220: 210–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, and Locati M. 2004. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol 25: 677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou D, Huang C, Lin Z, Zhan S, Kong L, Fang C, and Li J. 2014. Macrophage polarization and function with emphasis on the evolving roles of coordinated regulation of cellular signaling pathways. Cell Signal 26: 192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Striz I, Brabcova E, Kolesar L, and Sekerkova A. 2014. Cytokine networking of innate immunity cells: a potential target of therapy. Clin Sci (Lond) 126: 593–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhee I 2016. Diverse macrophages polarization in tumor microenvironment. Arch Pharm Res 39: 1588–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cassetta L, Cassol E, and Poli G. 2011. Macrophage polarization in health and disease. ScientificWorldJournal 11: 2391–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkins SJ, Ruckerl D, Cook PC, Jones LH, Finkelman FD, van Rooijen N, MacDonald AS, and Allen JE. 2011. Local macrophage proliferation, rather than recruitment from the blood, is a signature of TH2 inflammation. Science 332: 1284–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jenkins SJ, Ruckerl D, Thomas GD, Hewitson JP, Duncan S, Brombacher F, Maizels RM, Hume DA, and Allen JE. 2013. IL-4 directly signals tissue-resident macrophages to proliferate beyond homeostatic levels controlled by CSF-1. J Exp Med 210: 2477–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xue ML, Thakur A, Cole N, Lloyd A, Stapleton F, Wakefield D, and Willcox MD. 2007. A critical role for CCL2 and CCL3 chemokines in the regulation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils recruitment during corneal infection in mice. Immunol Cell Biol 85: 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bonville CA, Percopo CM, Dyer KD, Gao J, Prussin C, Foster B, Rosenberg HF, and Domachowske JB. 2009. Interferon-gamma coordinates CCL3-mediated neutrophil recruitment in vivo. BMC Immunol 10: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fahey TJ 3rd, Tracey KJ, Tekamp-Olson P, Cousens LS, Jones WG, Shires GT, Cerami A, and Sherry B. 1992. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1 modulates macrophage function. J Immunol 148: 2764–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terpos E, Politou M, Viniou N, and Rahemtulla A. 2005. Significance of macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1alpha) in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma 46: 1699–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steinle H, Behring A, Schlensak C, Wendel HP, and Avci-Adali M. 2017. Concise Review: Application of In Vitro Transcribed Messenger RNA for Cellular Engineering and Reprogramming: Progress and Challenges. Stem Cells 35: 68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.