The Caenorhabditis elegans genome encodes 40 insulin-like peptides, but the dynamics of insulin signaling both during development and in response to nutrient availability is not well understood. Kaplan and Maxwell et al. report that transcription of....

Keywords: daf-28, diapause, feedback, FoxO, FoxO-to-FoxO, homeostasis, ins-6, insulin, L1 arrest, starvation

Abstract

The Caenorhabditis elegans insulin-like signaling network supports homeostasis and developmental plasticity. The genome encodes 40 insulin-like peptides and one known receptor. Feedback regulation has been reported, but the extent of feedback and its effect on signaling dynamics in response to changes in nutrient availability has not been determined. We measured messenger RNA expression for each insulin-like peptide, the receptor daf-2, components of the PI3K pathway, and its transcriptional effectors daf-16/FoxO and skn-1/Nrf at high temporal resolution during transition from a starved, quiescent state to a fed, growing state in wild type and mutants affecting daf-2/InsR and daf-16/FoxO. We also analyzed the effect of temperature on insulin-like gene expression. We found that most PI3K pathway components and insulin-like peptides are affected by signaling activity, revealing pervasive positive and negative feedback regulation at intra- and intercellular levels. Reporter gene analysis demonstrated that the daf-2/InsR agonist daf-28 positively regulates its own transcription and that the putative agonist ins-6 cross-regulates DAF-28 protein expression through feedback. Our results show that positive and negative feedback regulation of insulin-like signaling is widespread, giving rise to an organismal FoxO-to-FoxO signaling network that supports homeostasis during fluctuations in nutrient availability.

INSULIN-LIKE signaling maintains homeostasis by responding to fluctuations in nutrient availability and altering gene expression. Work in Caenorhabditis elegans has shown that insulin-like signaling also allows developmental plasticity. For example, insulin-like signaling regulates whether larvae become reproductive or arrest as dauer larvae, a developmental diapause that occurs in unfavorable conditions (Hu 2007). Insulin-like signaling also contributes to continuous variations in phenotype; for example, in regulation of aging and growth rate (Murphy and Hu 2013). However, it is unclear how signaling dynamics are regulated such that the pathway can maintain a phenotypic steady state (homeostasis) or promote developmental plasticity, depending on conditions.

Insulin-like signaling is regulated by feedback in diverse animals. Pancreatic β cell-specific insulin receptor-knockout mice are poor at glucose sensing, have a diminished insulin secretory response, and tend to develop age-dependent diabetes (Otani et al. 2004). In addition, the full effect of glucose on pancreatic β cells grown in vitro requires the insulin receptor (Assmann et al. 2009). FoxO transcription factors, effectors of insulin signaling, activate transcription of insulin receptors in Drosophila and mammalian cells (Puig and Tjian 2005), suggesting a relatively direct, cell-autonomous mechanism for feedback regulation. However, evidence for such direct feedback regulation has not been found in C. elegans (Kimura et al. 2011).

Insulin-like signaling regulates the expression of insulin-like peptides in C. elegans, suggesting a relatively indirect, cell-nonautonomous mechanism for feedback regulation. The C. elegans genome encodes a family of 40 insulin-like peptides that can function as either agonists or antagonists of the only known insulin-like receptor daf-2 (Pierce et al. 2001). Systematic analyses of insulin-like peptide expression and function suggest substantial functional specificity rather than global redundancy (Ritter et al. 2013; Fernandes de Abreu et al. 2014). daf-2/InsR signals through a conserved phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway to antagonize the FoxO transcription factor daf-16 (Figure 1A; Murphy and Hu 2013). daf-16/FoxO represses transcription of the daf-2 agonist ins-7, creating positive feedback (Murphy et al. 2003). This positive feedback results in “FoxO-to-FoxO” signaling, which has been proposed to coordinate the physiological state of different tissues in the animal (Murphy et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2013; Alic et al. 2014). daf-16 also activates transcription of the daf-2 antagonist ins-18, again producing positive feedback (Murphy et al. 2003; Matsunaga et al. 2012a). Insulin-like peptide function has been reported to affect insulin-like peptide expression (Ritter et al. 2013; Fernandes de Abreu et al. 2014), consistent with feedback regulation. To the best of our knowledge, negative feedback regulation has not been reported despite the fact that homeostasis generally relies on it (Cannon 1929). Furthermore, the extent of feedback regulation is unknown.

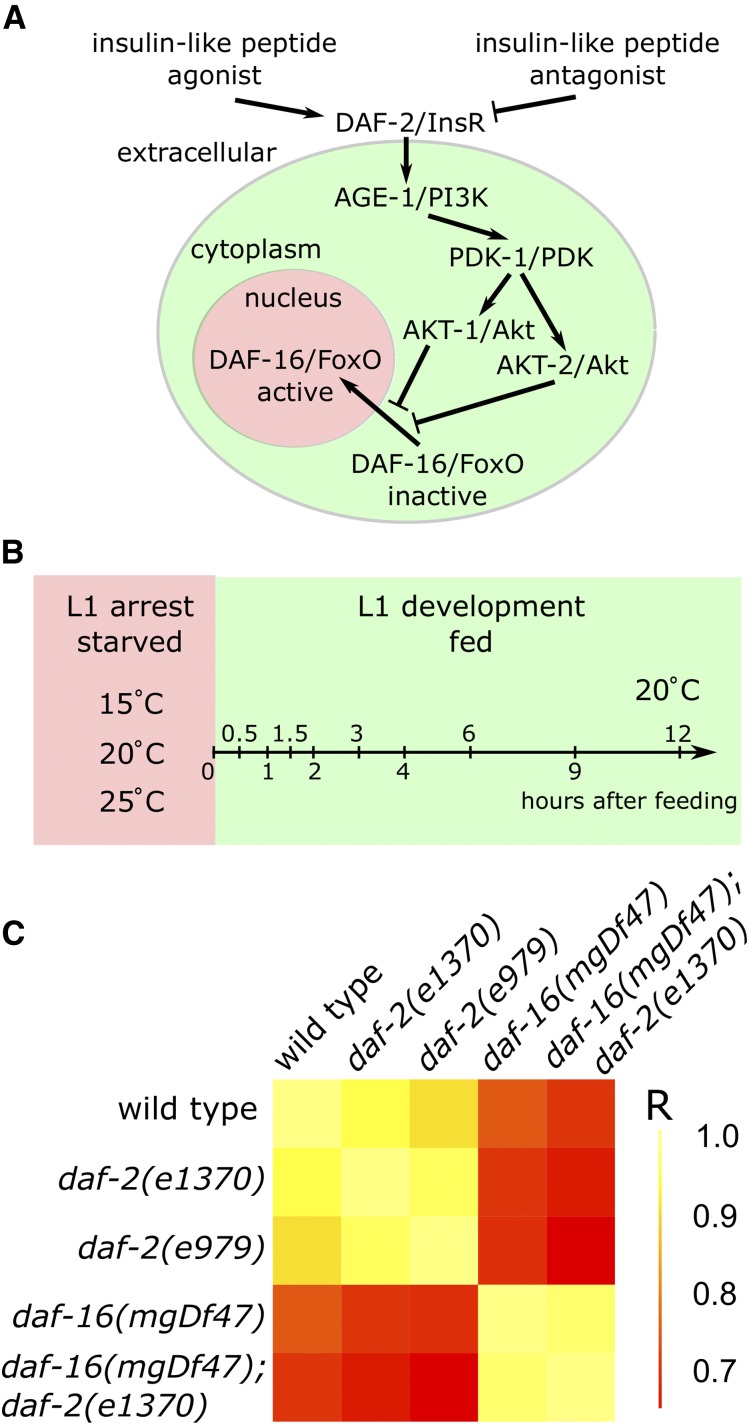

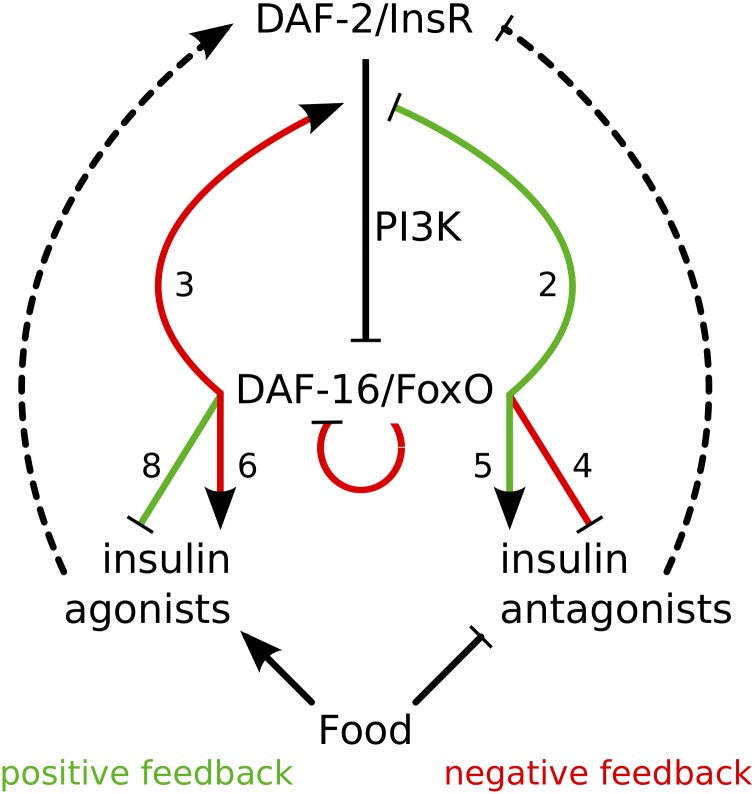

Figure 1.

daf-16/FoxO is epistatic to daf-2/InsR for expression of genes involved in insulin-like signaling. (A) A diagram of the C. elegans insulin-like signaling pathway. (B) A schematic of the experimental design with times and conditions sampled indicated. (C) A symmetric matrix of correlation coefficients for pairs of genotypes is presented as a heat map, with scale bar. Examination of individual gene expression patterns confirmed that daf-16 is epistatic to daf-2 in each instance with only a few relatively minor exceptions.

We sought to determine the extent of feedback regulation in insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. C. elegans larvae that hatch in the absence of food arrest development in the first larval stage (“L1 arrest” or “L1 diapause”), and insulin-like signaling regulates L1 arrest and development (Baugh 2013). We performed a genetic analysis of gene expression, measuring expression of all 40 insulin-like peptides as well as components of the PI3K pathway in daf-2/InsR and daf-16/FoxO mutants, which have perturbed signaling activity. We analyzed larvae in L1 arrest and over time after feeding, as they transition from quiescence to growth. The rationale is to infer feedback regulation by identifying genes that affect signaling activity and are themselves affected by signaling. We report extensive feedback, both positive and negative, acting relatively directly at the level of the PI3K pathway and also indirectly via regulation of peptide expression. This work suggests that feedback regulation of insulin-like signaling is pervasive and that this feedback functions to stabilize signaling activity during constant conditions while allowing rapid responses to new conditions.

Materials and Methods

Nematode culture and sample collection

The following C. elegans strains were used for gene expression analysis on the NanoString nCounter platform: N2 (wild type), PS5150 [daf-16(mgDf47)], CB1370 [daf-2(e1370)], DR1942 [daf-2(e979)], and GR1309 [daf-16(mgDf47); daf-2(e1370)]. Strains were maintained on NGM agar plates with Escherichia coli OP50 as food at 15° (DR1942) or 20° (all others). Liquid culture was used to obtain sufficiently large populations for time-series analysis with microgram quantities of total RNA. Larvae were washed from clean, starved plates with S-complete medium and used to inoculate liquid cultures (Lewis 1995). A single 6 cm plate was typically used, except with CB1370 and DR1942, for which two and three plates were used, respectively. Liquid cultures were comprised of S-complete medium and 40 mg/ml E. coli HB101. These cultures were incubated at 180 rpm and 15° for 4 days (with the exception of DR1942, which was incubated for 5 days), and eggs were prepared by standard hypochlorite treatment, yielding in excess of 100,000 eggs each. These eggs were used to set up another liquid culture again consisting of S-complete medium and 40 mg/ml HB101 but with a defined density of 5000 eggs/ml. These cultures were incubated at 180 rpm and 15° for 5 days (N2, PS5150, and GR1309), 6 days (CB1370), or 7 days (DR1942), and eggs were prepared by hypochlorite treatment with yields in excess of one million eggs per culture. These eggs were cultured in S-complete medium without food, at a density of 5000 eggs/ml at 180 rpm, so that eggs hatch and enter L1 arrest. For starved samples at 20° and 25°, they were cultured for 24 hr and collected, and for 15° they were cultured for 48 hr. Fed samples were cultured for 24 hr at 20°, and then 25 mg/ml HB101 was added to initiate recovery by feeding. Fed samples were collected at the time points indicated. Upon collection, larvae were quickly pelleted by spinning at 3,000 rpm for 10 sec, washed with S-basal medium and spun three times, transferred by Pasteur pipet to a 1.5 ml plastic tube in 100 μl of supernatant or less, and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were collected in at least two but typically three independent biological replicates where the entire culture and collection process was repeated.

RNA preparation and hybridization

Total RNA was prepared using 1 ml TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 3 μg total RNA was used for hybridization by NanoString (Seattle, WA), as described (Chen and Baugh 2014). The code set used included the same probes for all insulin-like genes as in Chen and Baugh (2014), with the exception of ins-13, which was replaced here. The code set also included probes for additional genes not included in Chen and Baugh (2014) (for a complete list of genes targeted see Supplemental Material, File S2) as well as standard positive and negative control probes.

Data analysis

nCounter results were normalized in a two-step procedure. First, counts for positive control probes (for which transcripts were spiked into the hybridization at known copy numbers) were used to normalize the total number of counts across all samples. Second, the total number of counts for all targeted genes except daf-16 (the deletion mutant used did not produce signal above background) was normalized across all samples. Insulin genes with a normalized count of <5000 were excluded from further analysis because they displayed a cross-hybridization pattern indicating that they were not reliably detected. The complete normalized data set is available in File S2.

Statistical analysis was used to assess the effects of daf-16 (in fed and starved samples) and temperature (starved samples only). For the effect of daf-16 in fed samples, two tests were used: a nonparametric ANCOVA with the null hypothesis that locally weighted smoothing (loess) lines connecting the points of the daf-16 single mutant (or the daf-16; daf-2 double mutant) and wild type [or daf-2(e1370)] are overlapping, such that the loess lines are not distinct. This test was implemented using the R package “sm” (Bowman and Azzalini 1997). For the effect of daf-16 in starved samples, two tests were used: a bootstrap test was used with the null hypothesis that the daf-16 single mutant (or the daf-16; daf-2 double mutant) has the same mean expression level as wild type (or daf-2(e1370)) for all temperatures. The effect size of genotype is calculated within each temperature, so it controls for temperature. Ten thousand permutations of genotype were calculated to get the P-value. For the effect of temperature during starvation, a chi-squared goodness-of-fit test was used to ask whether temperature explained additional variance in gene expression after controlling for genotype. Benjamini–Hochberg was used to calculate the “q-value” (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995), and these q-values were used to identify genes affected by daf-16 or temperature at a false-discovery rate of 5%. The complete results of the statistical analyses are available in File S1.

Pdaf-28::GFP reporter gene analysis

The mgIs40 [Pdaf-28::GFP] reporter (Li et al. 2003) was analyzed using the following genetic backgrounds and mutant alleles: wild type (N2), daf-16(mu86), daf-28(tm2308), ins-4(tm3620), ins-6(tm2416), and ins-4, 5, 6(hpDf761). Strains were maintained on NGM agar plates with E. coli OP50 as food at 20°. Eggs were prepared by standard hypochlorite treatment. These eggs were used to set up a liquid culture consisting of S-basal without ethanol or cholesterol with a defined density of 1000 eggs/ml. After 18 hr to allow for hatching, E. coli HB101 was added at 25 mg/ml to the fed samples. Six hours post food addition, the samples were washed three times with 10 ml S-basal and then run through the COPAS BioSorter measuring GFP fluorescence. Analysis of the COPAS data were performed in R. Tukey fences were used to remove outliers. Data points were also removed if they were determined to be debris by size or lack of fluorescence signal. This cleanup left a total of almost 165,000 data points for the first set of experiments (Figure 4B) and ∼95,500 data points for the second set of experiments (Figure 4C). Fluorescence data were normalized by optical extinction, a proxy for size. For the first set of experiments the Bartlett test of homogeneity of variances rejected the null hypothesis that the samples had equal variance. Therefore, unpaired t-tests with unequal variance were used to determine the significance of condition and genotype on mean normalized fluorescence. There were three biological replicates for the insulin-like peptide mutants and seven biological replicates for wild type and daf-16 mutants. For the second set of experiments the Bartlett test of homogeneity of variances did not reject the null hypothesis that the samples had equal variance Therefore, unpaired t-tests with equal variance were used to determine the significance of condition and genotype on mean normalized fluorescence. There were three biological replicates for all genotypes.

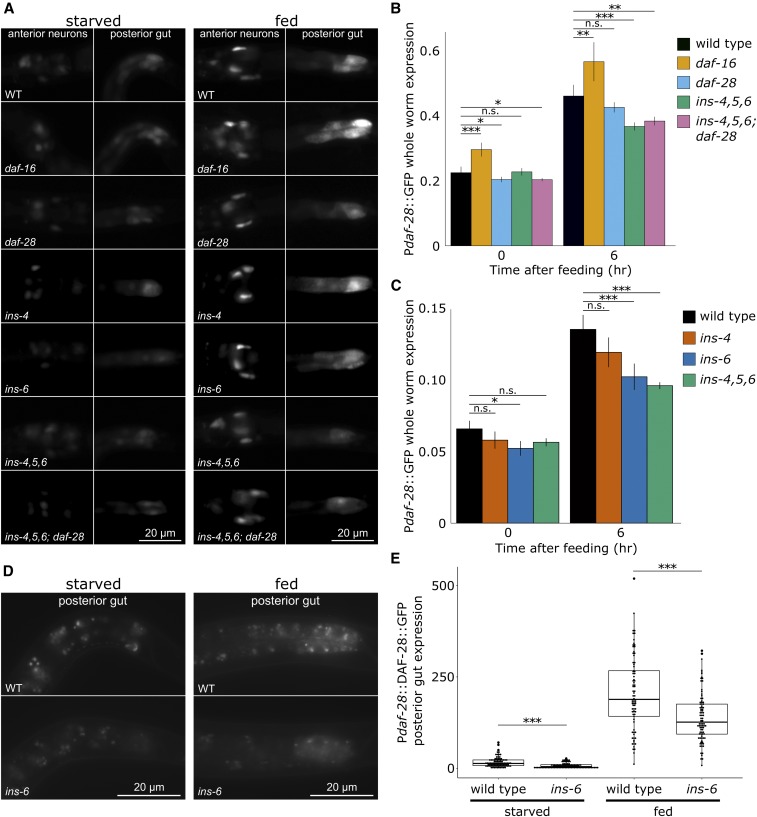

Figure 4.

Insulin-like peptide function affects expression of insulin-like peptides. (A) Representative images of a Pdaf-28::GFP transcriptional reporter gene are presented for wild type (WT) and various mutants in starved and fed (6 hr) L1 larvae, as indicated. Images were cropped and expression in anterior neurons and posterior gut is shown. (B and C) Quantitative analysis of Pdaf-28::GFP expression in whole worms using the COPAS BioSorter is presented. The grand average and SD of three to seven biological replicates is plotted for starved (0 hr) and fed (6 hr) L1 larvae. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 (unpaired t-test on replicate means, n = 3–7). Note that the COPAS BioSorter was recalibrated between experiments done for B and C, leading to different baseline values. (D) Representative images of a Pdaf-28::DAF-28::GFP translational reporter gene are presented for WT and ins-6 in starved and fed (17 hr) larvae, as indicated. Images were cropped and expression in posterior gut is shown. Expression remained dim after being fed for 6 hr, so it was instead analyzed after being fed for 17 hr. (E) Quantitative image analysis of Pdaf-28::DAF-28::GFP expression in posterior gut is presented. Each circle indicates the measurement from a single worm. Three biological replicates of 24–35 worms each were measured. *** P < 0.001 (linear mixed-effects model).

For imaging, the samples were prepared in the same way then paralyzed with 3.75 mM sodium azide and placed on an agarose pad on a microscope slide. Images were taken on an Axio Imager compound fluorescence microscope with an AxioCam camera (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Pdaf-28::DAF-28::GFP reporter gene analysis

The svIs69 [Pdaf-28::DAF-28::GFP] reporter (Kao et al. 2007) was analyzed using the following genetic backgrounds and mutant alleles: wild type (N2) and ins-6(tm2416). Strains were maintained on NGM agar plates with E. coli OP50 as food at 20°. Eggs were prepared by standard hypochlorite treatment. These eggs were used to set up a liquid culture consisting of S-basal without ethanol or cholesterol with a defined density of 1000 eggs/ml. After 24 hr to allow for hatching, E. coli HB101 was added at 25 mg/ml to the fed samples. At 17 hr post food addition, the samples were washed three times with 10 ml S-basal and then paralyzed with 3.75 mM sodium azide and placed on an agarose pad on a microscope slide. Images were taken on an Axio Imager compound fluorescent microscope with an AxioCam camera (Zeiss). Expression was quantified using the “Measure” function in ImageJ. Images were thresholded to minimize background, using N2 to establish a threshold value that would minimize the effect of autofluorescence. Expression was quantified as the mean fluorescence multiplied by the area of fluorescence. There were three biological replicates performed with 24–35 worms per condition per replicate. Analysis of the data were performed in R. A linear mixed-effect model was used to test for significance.

Motif analysis

FIMO from the MEME suite version 5.0.2 (Grant et al. 2011) was used to scan for occurrences of the DAF-16-binding element (DBE) and DAF-16-associated element 1000 bp upstream of the translational start site for each gene in Table 1. Default parameters were used, including a P-value cutoff of 10−4. Position-specific weight matrices for the DBE and DAE were from Tepper et al. (2013).

Table 1. Summary of genes regulated by daf-16/FoxO.

| Gene | Regulation by daf-16 | Putative function | Predicted feedback | DBE count | DAE count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| daf-2/InsR | repressed | insulin receptor | positive | 1 | 1 |

| age-1/PI3K | repressed | PI3K pathway | positive | 0 | 0 |

| pdk-1/PDK | activated | PI3K pathway | negative | 0 | 0 |

| akt-1/Akt | activated | PI3K pathway | negative | 0 | 0 |

| akt-2/Akt | activated | PI3K pathway | negative | 0 | 0 |

| skn-1/Nrf | repressed | insulin signaling effector | NA | 0 | 0 |

| daf-16/FoxO | repressed | insulin signaling effector | negative | 1 | 1 |

| sod-3/SOD | activated | known daf-16 target | NA | 2 | 0 |

| daf-28 | repressed | agonista,b,c,d,e,f,g | positive | 0 | 0 |

| ins-1 | repressed | antagonistb,h,d,e | negative | 1 | 0 |

| ins-3 | repressed | agonisti,d,e,g | positive | 0 | 0 |

| ins-4 | repressed | agonistc,d,e,f,g | positive | 0 | 2 |

| ins-5 | activated | agoniste,g | negative | 0 | 0 |

| ins-6 | activated | agonistb,c,d,e,f,g | negative | 0 | 0 |

| ins-9 | repressed | agonistf | positive | 0 | 0 |

| ins-11 | repressed | antagonistj,e,f | negative | 1 | 0 |

| ins-12 | activated | antagoniste | positive | 0 | 2 |

| ins-14 | repressed | agoniste | positive | 1 | 0 |

| ins-16 | activated | antagonistg | positive | 0 | 0 |

| ins-17 | repressed | antagonistk,g | negative | 0 | 0 |

| ins-18 | repressed | antagonisth,l,d,e,g | negative | 0 | 0 |

| ins-20 | activated | antagoniste,g | positive | 0 | 0 |

| ins-21 | repressed | agoniste,g | positive | 0 | 1 |

| ins-22 | repressed | agoniste,g | positive | 0 | 0 |

| ins-24 | activated | unknown | unknown | 1 | 0 |

| ins-25 | activated | antagonistg | positive | 0 | 0 |

| ins-26 | activated | agoniste,g | negative | 0 | 0 |

| ins-27 | activated | agoniste,g | negative | 0 | 0 |

| ins-28 | repressed | agoniste,g | positive | 1 | 0 |

| ins-29 | activated | antagonistg | positive | 1 | 0 |

| ins-30 | activated | unknown | unknown | 1 | 1 |

| ins-33 | activated | agonisti,e,g | negative | 1 | 1 |

| ins-35 | activated | agoniste,g | negative | 1 | 0 |

The gene, whether it is activated or repressed by daf-16, putative function of the gene, whether regulation is predicted to result in positive or negative feedback, and the number of occurrences of the DAF-16-binding element (DBE) and DAF-16-associated element (DAE) within 1000 bp upstream of the translation start is presented. Four total tests for regulation were considered [during L1 starvation at three different temperatures and during recovery over time after feeding, comparing daf-16(mgDf47) to wild type and also daf-16(mgDf47); daf-2(e1370) to daf-2(e1370)]. Results are considered significant if the P-value is < 0.05 in any one test after correction for multiple testing. See supplemental information for complete statistical analysis. Insulin-like peptides are predicted to function as agonists or antagonists of daf-2/InsR based on published genetic or expression analysis [Chen and Baugh (2014) is cited separately for results based on genetic or expression analysis; all other citations are for genetic analysis], and positive or negative feedback is predicted based on putative function (agonist or antagonist) and whether the gene is positively or negatively regulated by daf-16.

Chen and Baugh (2014): genetics.

Chen and Baugh (2014): expression.

Data availability

Complete results of statistical analysis is available in File S1. The complete normalized data set is available in File S2. Strains are available upon request. Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7318526.

Results

daf-2/InsR acts through daf-16/FoxO to affect gene expression

We used the NanoString nCounter platform to measure expression of genes related to insulin-like signaling in fed and starved L1 larvae at high temporal resolution during the transition between developmental arrest and growth (Malkov et al. 2009). Total RNA was prepared from whole worms and hybridized to a code set containing probes for all 40 insulin-like genes as well as components of the PI3K pathway and sod-3, a known DAF-16/FoxO target. In addition to wild type, we analyzed mutations affecting daf-2/InsR and daf-16/FoxO to ascertain the effects of insulin-like signaling activity on expression. We used the reference allele of daf-2, e1370, as well as a stronger allele, e979 (Gems et al. 1998). We used a null allele of daf-16, mgDf47, as well as a daf-16(mgDf47); daf-2(e1370) double mutant to analyze epistasis. Mutations affecting daf-2 are generally temperature sensitive, and insulin-like signaling responds to temperature. We therefore measured expression during L1 starvation at three different temperatures. We also fed bacteria to starved L1 larvae of each of the five genotypes and measured gene expression over time during recovery from L1 arrest in a highly synchronous population (Figure 1B). This experimental design enabled us to measure the effects of temperature, nutrient availability, and insulin-like signaling activity on genes related to insulin-like signaling itself during a critical physiological state transition.

daf-16/FoxO mediates the effects of daf-2/InsR on expression of genes involved in insulin-like signaling. daf-16 is required for canonical effects of daf-2, such as dauer formation and lifespan extension (Hu 2007; Murphy and Hu 2013). However, daf-2 also acts through other effector genes of the PI3K pathway, such as skn-1/Nrf (Tullet et al. 2008), as well as other signaling pathways, such as RAS (Nanji et al. 2005). In addition, genome-wide expression analyses of daf-16 have mostly been performed in a daf-2 mutant background (daf-2 vs. daf-16; daf-2) without analysis of wild type and/or daf-16 single mutants (Tepper et al. 2013), making analysis of epistasis between daf-2 and daf-16 with gene expression as a phenotype impossible. Since epistasis was not analyzed, these studies could not determine whether daf-16 mediated all of the effects of daf-2 on gene expression or if other effectors made a significant contribution. A correlation matrix between genotypes over all conditions tested indicates that mutating daf-2 affected expression, with a stronger effect of the e979 allele than e1370, as expected (Figure 1C). daf-16 also had a clear effect, and it was epistatic to daf-2. That is, the expression profile of the double mutant is similar to that of the daf-16 single mutant but not daf-2. Statistical analysis of individual genes together with examination of expression patterns across genotypes generally corroborated the results of correlation analysis, failing to identify genes with significant effects of daf-2 not mediated by daf-16 in the vast majority of cases. Interesting potential exceptions include ins-6, 9, and 27 at 25° during L1 starvation (Figure S2), although it should be noted that statistical significance of genotype at particular temperatures during L1 starvation was not assessed. These results show that daf-2 affects expression of genes involved in insulin-like signaling and that these effects are essentially mediated exclusively by daf-16, consistent with feedback regulation.

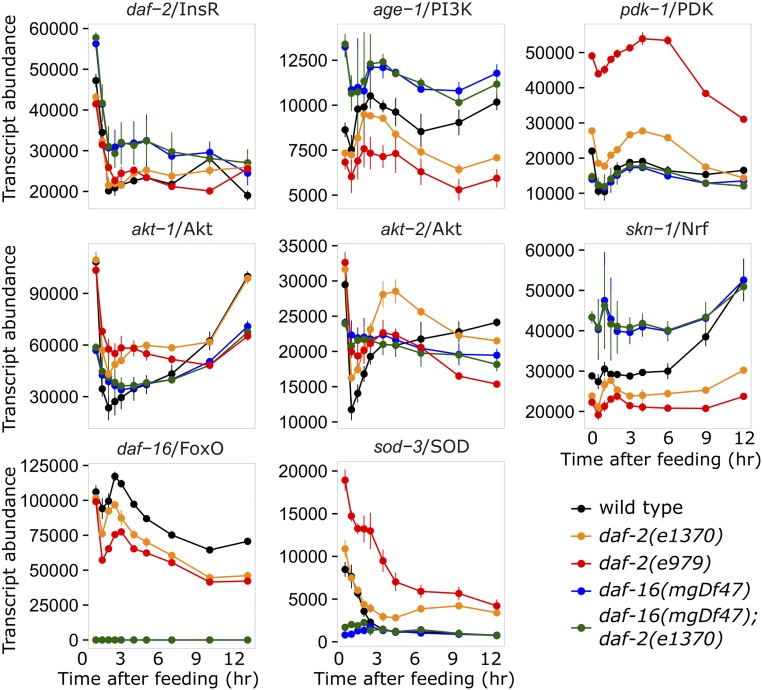

daf-16/FoxO affects expression of multiple PI3K pathway genes

We analyzed expression of several components of the PI3K pathway, as well as daf-2/InsR and its transcriptional effectors daf-16/FoxO and skn-1/Nrf (Lin et al. 1997; Ogg et al. 1997; Tullet et al. 2008). The known direct target of DAF-16, sod-3/SOD (Oh et al. 2006), was upregulated in daf-2 mutants and downregulated in the daf-16 mutant, with daf-16 epistatic to daf-2, in both starved and fed larvae (Figure 2, Figure S1, and Table 1). The exemplary behavior of this positive control demonstrates the validity of our experimental design. Notably, daf-16 expression drops to background levels in the daf-16 deletion mutant (Figure 2 and Figure S1), as expected. We previously reported that daf-2 is upregulated during L1 arrest (Chen and Baugh 2014). These results are consistent with that finding in that daf-2 expression decreases during recovery from L1 arrest, and we see here that daf-2 is actually repressed by daf-16 (Figure 2 and Figure S1). Notably, the probe used for daf-2 should recognize all known isoforms. Given that daf-2 is upregulated during starvation, when daf-16 is active, this result may be considered paradoxical. Our interpretation is that daf-2 expression is independently regulated by nutrient availability and daf-16 in opposing ways, illustrating regulatory complexity of the system. Nonetheless, since DAF-2 antagonizes DAF-16 activity via the PI3K pathway, these results indicate positive feedback between the only known insulin-like receptor and its FoxO transcriptional effector (Table 1). Likewise, age-1/PI3K, which transduces daf-2 signaling activity, was repressed by daf-16, also suggesting positive feedback. However, pdk-1/PDK, akt-1/Akt, and akt-2/Akt, downstream components of the PI3K pathway, were each activated by daf-16, albeit with relatively complex dynamics, suggesting negative feedback. Likewise, daf-16 expression is reduced in daf-2 mutants (Figure 2), where DAF-16 activity is increased, suggesting daf-16 represses its own transcription to produce negative feedback (Table 1). skn-1/Nrf expression was also reduced in daf-2 mutants and increased in daf-16 mutants, suggesting that insulin-like signaling positively regulates expression of both of its transcriptional effectors despite antagonizing their activity through phosphorylation. Based on statistical analysis, the effects of daf-16 mutation described here for each gene were consistent for fed and starved larvae, and whether comparing the effect of daf-16 in a wild-type or a daf-2(e1370) background (File S1). Regulation of each gene by daf-16 is therefore summarized as “activated,” “repressed,” or “not significant” in Table 1. However, akt-2 displayed complex expression dynamics in fed larvae that are not adequately summarized in this way (Figure 2 and Figure S1). In summary, daf-2/InsR signaling (which is assumed to represent insulin-like signaling) acts through daf-16/FoxO to regulate multiple critical components of the pathway itself, consistent with a combination of positive and negative cell-autonomous feedback regulation.

Figure 2.

Insulin-like signaling regulates expression of genes comprising the insulin-like signaling pathway. Transcript abundance (arbitrary units) is plotted over time during recovery from L1 starvation by feeding in five different genotypes with various levels of insulin-like signaling activity. In addition to daf-2/InsR and components of the PI3K pathway, the transcriptional effectors of signaling, daf-16/FoxO and skn-1/Nrf, are plotted as well as the known DAF-16 target sod-3. Note that daf-16 expression was not detected in daf-16 mutants. Each gene plotted was significantly affected by daf-16 (see Table 1, Table S1, and Supplemental Data). Error bars reflect the SEM of two or three biological replicates.

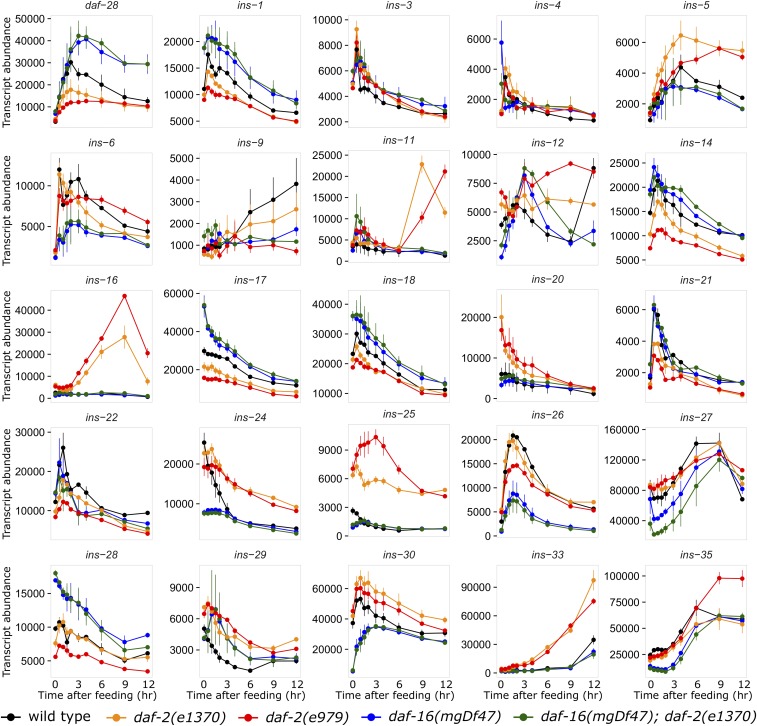

daf-16/FoxO affects expression of most insulin-like peptides

Insulin-like genes display complex dynamics in response to different levels of insulin-like signaling activity. Our code set contained probes for all 40 insulin-like genes, and we reliably detected expression for 28 of them (all but ins- 7, 8, 13, 15, 19, 23, 31, 32, 36, 37, 38, and 39). Similar to what we saw with components of the PI3K pathway (Figure 2, Figure S1, and Table 1), daf-16 appears to function as an activator of some genes and a repressor of others (Figure 3, Figure S2, and Table 1). For example, expression of daf-28, arguably the most studied insulin-like peptide in C. elegans (Li et al. 2003; Patel et al. 2008; Cornils et al. 2011; Chen and Baugh 2014; Fernandes de Abreu et al. 2014; Hung et al. 2014), was upregulated in daf-16 mutants and downregulated in daf-2 in starved and fed larvae (Figure 3, Figure S2, and Table 1), suggesting it is repressed by daf-16. Statistical analysis of the effect of daf-16 on each gene’s expression suggests that daf-16 function as an activator or repressor is consistent between fed and starved conditions, as for PI3K pathway genes (File S1). There may be several insulin-like genes (e.g., ins-29) whose expression gives the impression that regulation differs in fed and starved larvae (Figure 3 and Figure S2), but this interpretation is not supported by statistical analysis. Remarkably, all but three of the 28 reliably detected insulin-like genes were significantly affected by daf-16 (Table 1). Mutation of daf-16 caused upregulation of 12 insulin-like genes and downregulation of 13, suggesting that daf-16 directly or indirectly regulates transcription of most insulin-like genes.

Figure 3.

Insulin-like signaling regulates expression of the majority of insulin-like genes. Transcript abundance (arbitrary units) is plotted over time during recovery from L1 starvation by feeding in five different genotypes with various levels of insulin-like signaling activity. Of 28 reliably detected insulin-like genes, 25 were significantly affected by daf-16 (all but ins-2, -10, and -34; see Table 1, Table S1, and Supplemental Data) and are plotted. Error bars reflect the SEM of two or three biological replicates.

Inference of feedback as positive or negative is complicated by the fact that individual insulin-like peptides function as either agonists or antagonists of daf-2/InsR (Pierce et al. 2001). Biochemical data and structural modeling suggest that function as an agonist or antagonist is a property of the peptide (Matsunaga et al. 2018), as opposed to the context in which it is expressed. To infer whether the net effect of feedback regulation is positive or negative with respect to insulin-like signaling activity (daf-2/InsR activity), we took into account whether daf-16 appears to activate or repress the insulin-like gene and whether that gene encodes a putative agonist or antagonist. DAF-2 antagonizes DAF-16 activity, and so daf-16 repression or activation of an agonist or antagonist, respectively, would hypothetically result in positive feedback. daf-16 repression or activation of an antagonist or agonist, respectively, would hypothetically result in negative feedback. For example, daf-28 was originally identified on the basis of its constitutive dauer-formation phenotype. daf-28 is upregulated in rich conditions and it promotes dauer bypass (reproductive development), similar to daf-2/InsR, consistent with daf-28 functioning as an agonist of daf-2 (Li et al. 2003). daf-16 repression of daf-28 expression therefore suggests positive feedback in this case (Table 1).

A number of studies have performed genetic analysis of insulin-like peptide function, determining whether individual insulin-like genes have similar or opposite loss-of-function phenotypes to daf-2, and thus whether they presumably function as agonists or antagonists, respectively (Pierce et al. 2001; Li et al. 2003; Kawano et al. 2006; Patel et al. 2008; Michaelson et al. 2010; Cornils et al. 2011; Matsunaga et al. 2012a,b; Chen and Baugh 2014; Fernandes de Abreu et al. 2014; Hung et al. 2014). When we previously analyzed expression of insulin-like peptides in starved and fed L1 larvae, we found remarkable concordance between function (agonist or antagonist) and expression (positive or negative effect of food, respectively) (Chen and Baugh 2014). Out of 13 insulin-like peptides consistently found to function as putative agonists or antagonists based on genetic analysis, we classified all 13 the same way based on expression, while also classifying eight additional peptides. This classification relied on separate time-series analyses of starved and fed larvae (Chen and Baugh 2014), and inspection of the fed time series here did not reveal discrepancies between the two studies. We therefore included our previous putative functional classifications based on nutrient-dependent expression in Table 1, which tentatively assigns function to all but two of the 25 genes affected by daf-16. As explained above, putative agonists repressed by daf-16, like daf-28, hypothetically result in positive feedback, since daf-2 signaling antagonizes daf-16. We identified seven genes like this in addition to daf-28. Conversely, activation of a putative antagonist should also produce positive feedback, which we infer in five cases, while activation of an agonist should produce negative feedback, which we infer in six cases. Finally, repression of a putative antagonist should produce negative feedback, which we infer in four cases. In summary, activation and repression of putative agonists and antagonists by daf-16 is common, with positive and negative feedback hypothetically resulting from each different regulatory combination in multiple instances.

Temperature affects insulin-Like gene expression

We analyzed expression of insulin-like genes at 15, 20, and 25° during L1 starvation. daf-2 mutants are generally temperature-sensitive (Gems et al. 1998), daf-16 is localized to the nucleus at high temperatures (Henderson and Johnson 2001), and daf-2 mutants are heat-resistant (Munoz and Riddle 2003). These observations suggest that insulin-like signaling responds to temperature. We hypothesized that temperature sensitivity results at least in part from temperature-dependent regulation of insulin-like peptide expression. Consistent with daf-16 being active at elevated temperature, expression of its direct target sod-3 was positively affected by temperature (Figure S1 and Table S1). In support of our hypothesis, temperature affected messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of 21 out of 28 reliably detected insulin-like genes (Figure S2 and Table S1). daf-28 expression was lower at higher temperatures, consistent with its role in promoting dauer bypass (Li et al. 2003), and confirmed in a recent publication (O’Donnell et al. 2018). Expression of 12 insulin-like genes was lower at higher temperatures and nine were expressed higher at higher temperatures. However, there is no apparent correlation between putative function as agonist or antagonist and positive or negative regulation in response to higher temperature. This observation suggests that temperature sensitivity of insulin-like signaling is not generally due to temperature-dependent regulation of insulin-like gene expression, although the functional consequences of altered expression likely varies among insulin-like genes (e.g., daf-28, a potent agonist that is negatively regulated by temperature). Notably, although most insulin-like genes displayed significant temperature-dependent expression, the effect of temperature on expression was minor compared to nutrient availability.

Feedback mediates cross-regulation among insulin-Like genes

Reporter gene analysis validated the effect of daf-16/FoxO on daf-28 expression. We previously used quantitative RT-PCR to validate the nCounter approach to measuring insulin-like gene expression in C. elegans (Baugh et al. 2011), and we used transcriptional reporter genes to confirm positive regulation of several putative agonists in fed larvae, including daf-28 (Chen and Baugh 2014). A different Pdaf-28::GFP transcriptional reporter gene (Li et al. 2003) again confirmed upregulation in response to feeding (Figure 4A). Expression was evident but faint in anterior neurons and posterior intestine of starved L1 larvae, and it was brighter after being fed for 6 hr. Quantification of whole-animal fluorescence with the COPAS BioSorter provided robust statistical support for qualitative observations (Figure 4B). Critically, expression appeared elevated in daf-16 mutants compared to wild type, in both starved and fed larvae (Figure 4A). However, we did not observe a difference in the anatomical expression pattern in daf-16 compared to wild type. Quantification showed that the effect of daf-16 is statistically significant (Figure 4B). Note that the statistics for this analysis were performed on the means of individual biological replicates, as opposed to each individual in a replicate. Thus, statistical significance is due to reproducibility between trials despite relatively small effect sizes. The effect of food was larger than that of daf-16, as expected based on nCounter results (Figure 3). In addition, the effects of food and daf-16 are independent, suggesting that upregulation of daf-28 in response to feeding is not simply due to inhibition of daf-16 leading to derepression of daf-28. These results support the conclusion that daf-16 represses daf-28 transcription, consistent with feedback regulation.

Widespread feedback regulation of insulin-like signaling via transcriptional control of insulin-like peptides suggests that activity of individual insulin-like genes should affect expression of themselves. We analyzed expression of the Pdaf-28::GFP transcriptional reporter in insulin mutants to test this hypothesis. Pdaf-28::GFP transgene expression was significantly reduced during L1 arrest in a daf-28 mutant compared to wild type (Figure 4, A and B). This result suggests that positive feedback mediated by daf-16 repression of daf-28, daf-28 agonism of daf-2/InsR, and daf-2 inhibition of daf-16 results in daf-28 effectively promoting its own expression.

Widespread feedback regulation also suggests that activity of individual insulin-like genes should affect expression of other insulin-like genes. daf-28, ins-4, and ins-6 coordinately regulate dauer entry and exit (Li et al. 2003; Cornils et al. 2011; Hung et al. 2014), and they redundantly promote L1 development in response to feeding (Chen and Baugh 2014). ins-4, -5, and -6 are in a chromosomal cluster, so we analyzed a deletion allele that removes all three (Hung et al. 2014). Pdaf-28::GFP expression was significantly reduced in fed larvae of the ins-4, 5, 6 mutant compared to wild type (Figure 4, A and B). Simultaneous disruption of ins-4, 5, 6 and daf-28 in a compound mutant significantly reduced Pdaf-28::GFP expression in both starved and fed L1 larvae (Figure 4B). These results suggest that feedback regulation results in cross-regulation among insulin-like peptides such that the function of one peptide affects the transcription of others.

Analysis of the ins-4, 5, 6 deletion mutant revealed cross-regulation of daf-28 transcription, but it did not identify an individual insulin-like gene responsible for cross-regulation. Overexpression analysis (which circumvents genetic redundancy) of ins-4, ins-5, and ins-6 individually during L1 arrest and development revealed functional effects of ins-4 and ins-6 but not ins-5 (Chen and Baugh 2014). We therefore hypothesized that loss of function of ins-4 or ins-6 alone could affect daf-28 expression. The ins-4, 5, 6 deletion mutant significantly reduced Pdaf-28::GFP expression in fed larvae (Figure 4C), as expected (Figure 4B). An ins-4 deletion mutant reduced Pdaf-28::GFP expression in fed and starved L1 larvae, but this effect was not statistically significant. However, an ins-6 deletion mutant significantly reduced Pdaf-28::GFP expression in fed and starved larvae (Figure 4C). These results suggest that loss of ins-6 function is the primary driver of the effect of the ins-4, 5, 6 deletion mutant on Pdaf-28::GFP expression, although ins-4 may also contribute. In summary, ins-6 (a putative daf-2/InsR agonist) positively regulates daf-28 expression via daf-2 inhibition of daf-16 and daf-16–mediated repression of daf-28 transcription.

We sought to confirm that effects on transcriptional regulation revealed by analyses of mRNA and Pdaf-28::GFP expression translate to differences in DAF-28 protein expression, as would be required for a functional FoxO-to-FoxO signaling network. We therefore analyzed expression of a secreted, functional Pdaf-28::DAF-28::GFP translational reporter (Kao et al. 2007) in wild type and an ins-6 deletion mutant. Expression of this reporter was hardly visible in anterior neurons and posterior intestine during L1 arrest, but intestinal expression appeared brighter after feeding and dimmer in the ins-6 mutant compared to wild type in fed and starved larvae (Figure 4D). Expression was too dim for whole-worm analysis on the BioSorter, so we performed quantitative image analysis of posterior intestinal expression. Image analysis revealed significantly lower translational reporter expression in the ins-6 mutant compared to wild type in starved and fed larvae (Figure 4E), consistent with transcriptional reporter analysis (Figure 4, A–C). These results suggest that cross-regulation of daf-28 transcription by ins-6, and likely other insulin-like peptides, affects DAF-28 protein expression. In summary, reporter gene analysis suggests physiological significance of feedback regulation, consistent with function of individual insulin-like peptides affecting expression of themselves and others to produce an organismal FoxO-to-FoxO signaling network.

Discussion

We determined the extent of feedback regulation of insulin-like signaling in C. elegans in starved and fed L1 larvae. We show that mRNA expression of nearly all detectable insulin-like genes is affected by insulin-like signaling activity, revealing pervasive feedback regulation. We also show that several components of the PI3K pathway, including daf-2/InsR and daf-16/FoxO, are affected by signaling activity. Together these results suggest that feedback occurs inter- and intracellularly (Figure 5). Furthermore, we show that feedback is positive and negative at both levels of regulation. Finally, we demonstrate that feedback regulation results in auto- and cross-regulation of insulin-like gene expression.

Figure 5.

Pervasive feedback regulation of insulin-like signaling. daf-2/InsR antagonizes daf-16/FoxO via the PI3K pathway (Figure 1). daf-16 activates expression of three pathway components to produce negative feedback, and it represses expression of two components to produce positive feedback. daf-16 also represses its own expression, producing negative feedback, and it represses expression of skn-1/Nrf (not depicted). daf-16 represses expression of eight putative insulin-like peptide agonists of daf-2 and activates five putative antagonists, producing positive feedback in each case. daf-16 also activates six putative agonists and represses four putative antagonists, producing negative feedback. Food activates expression of agonists and represses expression of antagonists (by definition with corroboration from functional analysis; Chen and Baugh 2014), independent of daf-16 and insulin-like signaling. Nutrient availability also affects daf-2 expression independent of insulin-like signaling activity (not depicted). Dashed arrows reflect putative function of insulin-like peptides as agonists or antagonists of daf-2, reflecting cell-nonautonomous effects of daf-16 and nutrient availability. Inferred positive feedback is depicted in green and negative feedback in red. Numbers next to colored arrows indicate the number of genes represented by each arrow.

We detected substantially more regulation of insulin-like genes by daf-16/FoxO than previously reported in genome-wide expression analyses. We also detected extensive effects of temperature on insulin-like gene expression. In contrast to other expression analyses, our analysis used highly synchronous populations of larvae, improving sensitivity. Sensitivity was also likely improved by focusing on proximal effects of nutrient availability, which has robust effects on insulin-like signaling. In addition, the nCounter assay conditions used are optimized for sensitivity and precision (Baugh et al. 2011), improving power to detect differential expression. We also analyzed the effects of daf-16 mutation in a wild-type background as well as a daf-2 mutant background, in fed and starved larvae, producing four independent opportunities to detect an effect of daf-16. Finally, we sampled extensively, not only with biological replicates, but also with three different temperatures during L1 arrest as well as nine time points after feeding. Taken together, these features likely explain why we detected such extensive effects. Nonetheless, expression of ins-7, a putative agonist that regulates aging in adults, was not reliably detected, consistent with our previous analysis of insulin-like gene expression using the nCounter platform throughout the lifecycle and in L1 larvae (Baugh et al. 2011; Chen and Baugh 2014). We therefore cannot assess regulation of ins-7 in L1 larvae, although it was the first example of positive feedback regulation and FoxO-to-FoxO signaling (Murphy et al. 2003, 2007).

Other nutrient-dependent pathways also regulate expression of insulin-like genes and PI3K pathway components. That is, insulin-like signaling does not account for all of the observed effects of nutrient availability on gene expression (Figure 5). For example, we show that daf-28 expression is upregulated in response to feeding and that it is repressed by daf-16/FoxO. Since DAF-16 is nuclear and active during starvation and is excluded from the nucleus in response to feeding (Henderson and Johnson 2001), it is conceivable that upregulation of daf-28 in response to feeding is due to inactivation of DAF-16 and derepression of daf-28. However, this model predicts that daf-28 expression should be equivalent in starved and fed daf-16 mutant larvae, but it is not. To the contrary, induction of daf-28 in fed larvae occurs with similar magnitude in each genotype tested. This was true with mRNA expression analysis by nCounter as well as transcriptional reporter gene analysis. Despite numerous examples of daf-2 and daf-16 affecting expression, the effects of nutrient availability are generally evident in all genotypes, indicating the influence of other nutrient-dependent pathways (Figure 5).

Our results highlight the complexity of regulation of insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. 25 of 28 reliably detected insulin-like genes were affected by insulin-like signaling, suggesting they participate in feedback regulation. All patterns of regulation were observed for putative daf-2/InsR agonists and antagonists, supporting the conclusion that agonists and antagonists both contribute to positive and negative feedback regulation (Figure 5). In addition, daf-16 regulation appears to depend on developmental stage. ins-18, a putative antagonist, contributes to positive feedback via daf-16 activation in adults (Matsunaga et al. 2012a). However, our results suggest that daf-16 represses ins-18 in L1 larvae. Furthermore, ins-21, a putative agonist, is upregulated in daf-2 mutant L4 larvae, as if activated by daf-16 (Fernandes de Abreu et al. 2014), while our results show it being repressed by daf-16. These results for ins-18 and ins-21 suggest that whether daf-16 regulation is positive or negative, it is stage- and possibly condition-specific, such that individual insulin-like genes may participate in positive or negative feedback depending on context. Our results also hint at the idea that the strength of insulin-like signaling could affect whether regulation is positive or negative. That is, ins-5, 9, 24, 26, and 30 each display a curious inversion in the effect of daf-2 activity at some time of recovery from L1 starvation, with the stronger daf-2(e979) allele displaying a weaker effect than daf-2(e1370). This result may reflect cross-regulation by other signaling activities that remain to be identified.

We provide evidence that daf-16/FoxO activity leads to activation and repression of genes involved in insulin-like signaling. However, we used genetic and not biochemical analysis, so we do not know if DAF-16 regulation is direct or indirect. DAF-16 is thought to function primarily as an activator (Schuster et al. 2010; Riedel et al. 2013), with repression (“class II” targets) occurring indirectly via its antagonism of the transcriptional activator PQM-1 (Tepper et al. 2013). DAF-16 is thought to bind the DAF-16-binding element (DBE) to mediate activation of its direct targets, and PQM-1 is thought to bind the DAF-16-associated element (DAE) to indirectly mediate repression (Tepper et al. 2013). We analyzed occurrences of the DBE and DAE motifs upstream of the genes we found to be daf-16–dependent, but no clear pattern with respect to activation or repression emerged (Table 1). However, this is a relatively small set of genes for motif analysis, and a role of pqm-1 in L1 larvae has not been investigated. Nonetheless, akt-1/Akt, akt-2/Akt, skn-1/Nrf, and daf-16/FoxO were each included on a list of 65 high-confidence direct DAF-16 targets (Schuster et al. 2010). We found each of these to be regulated by daf-16, with skn-1 and daf-16 being repressed, consistent with possible direct repression independent of PQM-1. Mechanistic details aside, this work reveals extensive positive and negative feedback regulation of insulin-like signaling.

Insulin-like peptide function regulates expression of insulin-like genes. We used reporter gene analysis to show that function of daf-28, a daf-2 agonist repressed by daf-16, affects its own transcription. Furthermore, we showed that another agonist, ins-6, cross-regulates daf-28 transcription, with an effect on DAF-28 protein expression. These results are consistent with reports of insulin-like peptides affecting expression of other insulin-like genes (Ritter et al. 2013; Fernandes de Abreu et al. 2014), although in this case we demonstrate an intermediary effect of daf-16/FoxO. Given that we found most insulin-like genes to be regulated by insulin-like signaling, cross-regulation among insulin-like peptides is likely common, giving rise to an organismal FoxO-to-FoxO signaling network.

We believe the physiological significance of feedback regulation is to stabilize signaling activity in variable environments. Negative feedback supports homeostasis, returning the system to a stable steady state (Cannon 1929). In contrast, positive feedback supports rapid responses and switch-like behavior (Ingolia and Murray 2007). We speculate that by combining negative and positive feedback, the insulin-like signaling system is able to maintain homeostasis at different set points of signaling activity. That is, in constant conditions negative feedback stabilizes signaling activity, but when conditions change (e.g., differences in nutrient availability), positive feedback allows signaling activity to respond rapidly and negative feedback helps it settle to a new steady state rather than displaying runaway dynamics. Notably, this combination of positive and negative regulation is seen intracellularly in regulation of PI3K pathway components as well as intercellularly in regulation of insulin-like genes. In addition, signaling occurs in the context of a multicellular animal, with tissues and organs that presumably vary in their energetic and metabolic demands. Consequently, FoxO-to-FoxO signaling resulting from feedback may be relatively positive or negative in different anatomical regions, governed by the peptides involved, serving to coordinate the animal’s physiology appropriately (McMillen et al. 2002; Kaplan and Baugh 2016). In any case, the extent of feedback suggests that it is a very important means of regulation. We imagine that insulin-like signaling in other animals, as well as other endocrine signaling systems, are also rife with feedback, and that feedback is critical to system dynamics.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank NanoString, Inc., for performing nCounter hybridizations for us. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (grant P40 OD010440). The National Science Foundation (LRB grant IOS-1120206) and the National Institutes of Health (LRB R01GM117408) funded this work. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions: L.R.B. conceived of the study and provided funding. L.R.B., R.E.W.K. and N.K.C. performed the experiments. C.S.M. and R.E.W.K. analyzed the data. L.R.B., C.S.M., and R.E.W.K. prepared the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7318526.

Communicating editor: V. Reinke

Literature Cited

- Alic N., Tullet J. M., Niccoli T., Broughton S., Hoddinott M. P., et al. , 2014. Cell-nonautonomous effects of dFOXO/DAF-16 in aging. Cell Reports 6: 608–616. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann A., Ueki K., Winnay J. N., Kadowaki T., Kulkarni R. N., 2009. Glucose effects on beta-cell growth and survival require activation of insulin receptors and insulin receptor substrate 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29: 3219–3228. 10.1128/MCB.01489-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh L. R., 2013. To grow or not to grow: nutritional control of development during Caenorhabditis elegans L1 arrest. Genetics 194: 539–555. 10.1534/genetics.113.150847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh L. R., Kurhanewicz N., Sternberg P. W., 2011. Sensitive and precise quantification of insulin-like mRNA expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One 6: e18086 10.1371/journal.pone.0018086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y., 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman A. W., Azzalini A., 1997. Applied Smoothing Techniques for Data Analysis: The Kernel Approach With S-Plus Illustrations. Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon W. B., 1929. Organization for physiological homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 9: 399–431. 10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Baugh L. R., 2014. Ins-4 and daf-28 function redundantly to regulate C. elegans L1 arrest. Dev. Biol. 394: 314–326. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornils A., Gloeck M., Chen Z., Zhang Y., Alcedo J., 2011. Specific insulin-like peptides encode sensory information to regulate distinct developmental processes. Development 138: 1183–1193. 10.1242/dev.060905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes de Abreu D. A., Caballero A., Fardel P., Stroustrup N., Chen Z., et al. , 2014. An insulin-to-insulin regulatory network orchestrates phenotypic specificity in development and physiology. PLoS Genet. 10: e1004225 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gems D., Sutton A. J., Sundermeyer M. L., Albert P. S., King K. V., et al. , 1998. Two pleiotropic classes of daf-2 mutation affect larval arrest, adult behavior, reproduction and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 150: 129–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant C. E., Bailey T. L., Noble W. S., 2011. FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 27: 1017–1018. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S. T., Johnson T. E., 2001. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 11: 1975–1980. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00594-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P. J., 2007 Dauer (August 08, 2007), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, /10.1895/wormbook.1.144.1, http://www.wormbook.org.

- Hung W. L., Wang Y., Chitturi J., Zhen M., 2014. A Caenorhabditis elegans developmental decision requires insulin signaling-mediated neuron-intestine communication. Development 141: 1767–1779. 10.1242/dev.103846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia N. T., Murray A. W., 2007. Positive-feedback loops as a flexible biological module. Curr. Biol. 17: 668–677. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G., Nordenson C., Still M., Ronnlund A., Tuck S., et al. , 2007. ASNA-1 positively regulates insulin secretion in C. elegans and mammalian cells. Cell 128: 577–587. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R. E., Baugh L. R., 2016. L1 arrest, daf-16/FoxO and nonautonomous control of post-embryonic development. Worm 5: e1175196 10.1080/21624054.2016.1175196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T., Nagatomo R., Kimura Y., Gengyo-Ando K., Mitani S., 2006. Disruption of ins-11, a Caenorhabditis elegans insulin-like gene, and phenotypic analyses of the gene-disrupted animal. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70: 3084–3087. 10.1271/bbb.60472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K. D., Riddle D. L., Ruvkun G., 2011. The C. elegans DAF-2 insulin-like receptor is abundantly expressed in the nervous system and regulated by nutritional status. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 76: 113–120. 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. A., Fleming J. T., 1995. Basic Culture Methods, pp. 4–27 in Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern biological Analysis of an Organism, edited by Epstein H. F., Shakes D. C., Academic Press, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Kennedy S. G., Ruvkun G., 2003. daf-28 encodes a C. elegans insulin superfamily member that is regulated by environmental cues and acts in the DAF-2 signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 17: 844–858. 10.1101/gad.1066503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K., Dorman J. B., Rodan A., Kenyon C., 1997. daf-16: an HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 278: 1319–1322. 10.1126/science.278.5341.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkov V. A., Serikawa K. A., Balantac N., Watters J., Geiss G., et al. , 2009. Multiplexed measurements of gene signatures in different analytes using the Nanostring nCounter assay system. BMC Res. Notes 2: 80 10.1186/1756-0500-2-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga Y., Gengyo-Ando K., Mitani S., Iwasaki T., Kawano T., 2012a. Physiological function, expression pattern, and transcriptional regulation of a Caenorhabditis elegans insulin-like peptide, INS-18. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 423: 478–483. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga Y., Nakajima K., Gengyo-Ando K., Mitani S., Iwasaki T., et al. , 2012b. A Caenorhabditis elegans insulin-like peptide, INS-17: its physiological function and expression pattern. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 76: 2168–2172. 10.1271/bbb.120540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga Y., Matsukawa T., Iwasaki T., Nagata K., Kawano T., 2018. Comparison of physiological functions of antagonistic insulin-like peptides, INS-23 and INS-18, in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 82: 90–96. 10.1080/09168451.2017.1415749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen D., Kopell N., Hasty J., Collins J. J., 2002. Synchronizing genetic relaxation oscillators by intercell signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 679–684. 10.1073/pnas.022642299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson D., Korta D. Z., Capua Y., Hubbard E. J., 2010. Insulin signaling promotes germline proliferation in C. elegans. Development 137: 671–680. 10.1242/dev.042523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz M. J., Riddle D. L., 2003. Positive selection of Caenorhabditis elegans mutants with increased stress resistance and longevity. Genetics 163: 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C. T., Hu P. J., 2013. Insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling in C. elegans (December 26, 2013), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, /10.1895/wormbook.1.164.1, http://www.wormbook.org. 10.1895/wormbook.1.164.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C. T., McCarroll S. A., Bargmann C. I., Fraser A., Kamath R. S., et al. , 2003. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 424: 277–283. 10.1038/nature01789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C. T., Lee S. J., Kenyon C., 2007. Tissue entrainment by feedback regulation of insulin gene expression in the endoderm of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19046–19050. 10.1073/pnas.0709613104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanji M., Hopper N. A., Gems D., 2005. LET-60 RAS modulates effects of insulin/IGF-1 signaling on development and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 4: 235–245. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00166.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell M. P., Chao P. H., Kammenga J. E., Sengupta P., 2018. Rictor/TORC2 mediates gut-to-brain signaling in the regulation of phenotypic plasticity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 14: e1007213 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S., Paradis S., Gottlieb S., Patterson G. I., Lee L., et al. , 1997. The Fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature 389: 994–999. 10.1038/40194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. W., Mukhopadhyay A., Dixit B. L., Raha T., Green M. R., et al. , 2006. Identification of direct DAF-16 targets controlling longevity, metabolism and diapause by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Nat. Genet. 38: 251–257. 10.1038/ng1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani K., Kulkarni R. N., Baldwin A. C., Krutzfeldt J., Ueki K., et al. , 2004. Reduced beta-cell mass and altered glucose sensing impair insulin-secretory function in betaIRKO mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286: E41–E49. 10.1152/ajpendo.00533.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D. S., Fang L. L., Svy D. K., Ruvkun G., Li W., 2008. Genetic identification of HSD-1, a conserved steroidogenic enzyme that directs larval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 135: 2239–2249. 10.1242/dev.016972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S. B., Costa M., Wisotzkey R., Devadhar S., Homburger S. A., et al. , 2001. Regulation of DAF-2 receptor signaling by human insulin and ins-1, a member of the unusually large and diverse C. elegans insulin gene family. Genes Dev. 15: 672–686. 10.1101/gad.867301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig O., Tjian R., 2005. Transcriptional feedback control of insulin receptor by dFOXO/FOXO1. Genes Dev. 19: 2435–2446. 10.1101/gad.1340505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel C. G., Dowen R. H., Lourenco G. F., Kirienko N. V., Heimbucher T., et al. , 2013. DAF-16 employs the chromatin remodeller SWI/SNF to promote stress resistance and longevity. Nat. Cell Biol. 15: 491–501. 10.1038/ncb2720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter A. D., Shen Y., Fuxman Bass J., Jeyaraj S., Deplancke B., et al. , 2013. Complex expression dynamics and robustness in C. elegans insulin networks. Genome Res. 23: 954–965. 10.1101/gr.150466.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster E., McElwee J. J., Tullet J. M., Doonan R., Matthijssens F., et al. , 2010. DamID in C. elegans reveals longevity-associated targets of DAF-16/FoxO. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6: 399 10.1038/msb.2010.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper R. G., Ashraf J., Kaletsky R., Kleemann G., Murphy C. T., et al. , 2013. PQM-1 complements DAF-16 as a key transcriptional regulator of DAF-2-mediated development and longevity. Cell 154: 676–690. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullet J. M., Hertweck M., An J. H., Baker J., Hwang J. Y., et al. , 2008. Direct inhibition of the longevity-promoting factor SKN-1 by insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. Cell 132: 1025–1038. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Judy M., Lee S. J., Kenyon C., 2013. Direct and indirect gene regulation by a life-extending FOXO protein in C. elegans: roles for GATA factors and lipid gene regulators. Cell Metab. 17: 85–100. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Complete results of statistical analysis is available in File S1. The complete normalized data set is available in File S2. Strains are available upon request. Supplemental material available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.7318526.