Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: hybrid ER, IVR-CT, TAE, trauma workflow, whole-body CT

Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of a novel trauma workflow, using an interventional radiology (IVR)–computed tomography (CT) system in severe trauma.

Background:

In August 2011, we installed an IVR-CT system in our trauma resuscitation room. We named it the Hybrid emergency room (ER), as it enabled us to perform all examinations and treatments required for trauma in a single place.

Methods:

This retrospective historical control study conducted in Japan included consecutive severe (injury severity score ≥16) blunt trauma patients. Patients were divided into 2 groups: Conventional (from August 2007 to July 2011) or Hybrid ER (from August 2011 to July 2015). We set the primary endpoint as 28-day mortality. The secondary endpoints included cause of death and time course from arrival to start of CT and surgery. Multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for clinically important variables was performed to evaluate the clinical outcomes.

Results:

We included 696 patients: 360 in the Conventional group and 336 in the Hybrid ER group. The Hybrid ER group was significantly associated with decreased mortality [adjusted odds ratio (OR), 0.50 (95% confidence interval, 95% CI, 0.29–0.85); P = 0.011] and reduced deaths from exsanguination [0.17 (0.06–0.47); P = 0.001]. The time to CT initiation [Conventional 26 (21 to 32) minutes vs Hybrid ER 11 (8 to 16) minutes; P < 0.0001] and emergency procedure [68 (51 to 85) minutes vs 47 (37 to 57) minutes; P < 0.0001] were both shorter in the Hybrid ER group.

Conclusion:

This novel trauma workflow, comprising immediate CT diagnosis and rapid bleeding control without patient transfer, as realized in the Hybrid ER, may improve mortality in severe trauma.

The advanced trauma life support (ATLS) guidelines have gained great acceptance worldwide as a standardized method of initial management protocols for patients with trauma.1 The importance of a physiological assessment is emphasized in the guidelines to immediately identify life-threatening conditions. Chest and pelvic radiography, as well as a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST), are the only recommended diagnostic devices in the primary survey. Although computed tomography (CT) has higher sensitivity in diagnosing potentially life-threatening injuries than radiography or FAST,2–4 it is a cause for concern that CT examinations in hemodynamically unstable patients may delay the surgical intervention and increase the number of potentially preventable deaths. The emergence of multidetector-row CT dramatically reduced the time taken for CT scanning.5 Furthermore, several institutions have installed CT scanners in their trauma resuscitation rooms to eliminate the transportation time.6–12

The application of an interventional radiology (IVR) system for trauma is another innovative development that has contributed to the treatment progress. Numerous studies have reported satisfactory success rates of the nonoperative management (NOM), which consists of an accurate diagnosis by contrast-enhanced CT and transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE).13–15 Thus, it is a standardized therapeutic option in hemodynamically stable patients with hepatic, splenic, and pelvic injuries. Furthermore, several institutions have expanded the indication of TAE to relatively unstable patients, based on advanced techniques and improved access to IVR.16 However, it should be noted that using NOM with TAE is based on the precise detection of hemorrhage sites by a contrast blush on CT.17,18 Therefore, the development of the technology and availability of CT and IVR can be key components in the future innovation of trauma care.

From these perspectives, we hypothesized that the improvement of access to both CT and IVR would greatly contribute to advancements in the management of trauma. In other words, eliminating the transfer time to these kinds of equipment would achieve an ideal trauma workflow. In August 2011, we installed a multi-slice IVR-CT system (Aquilion CX, TSX-101A; Toshiba Medical Systems Corp., Tochigi, Japan) in our trauma resuscitation room.19 It consisted of a carbon-fiber fluoroscopic table with a self-propelled C-arm combined with a sliding gantry CT scanner (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, showing the IVR-CT system in the Hybrid ER). The room was also equipped with a movable ultrasound, monitoring screen, and mechanical ventilator. As a result, it enabled us to perform both the examinations and life-saving procedures required for trauma—including radiography, ultrasonography, and CT, as well as damage control surgery, TAE, and burr hole craniostomy—on the same table without patient transfer. As the concept is based on a combination of an “examination” and “treatment” in the same space, we named the novel trauma resuscitation room the “Hybrid emergency room (Hybrid ER).”

In the present study, we evaluated the impact of our novel trauma workflow, using the Hybrid ER, on the mortality in patients with severe trauma.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted at a tertiary hospital in Osaka, Japan. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Osaka General Medical Center. The board waived the need for informed consent, as this was a retrospective study.

Patient Population

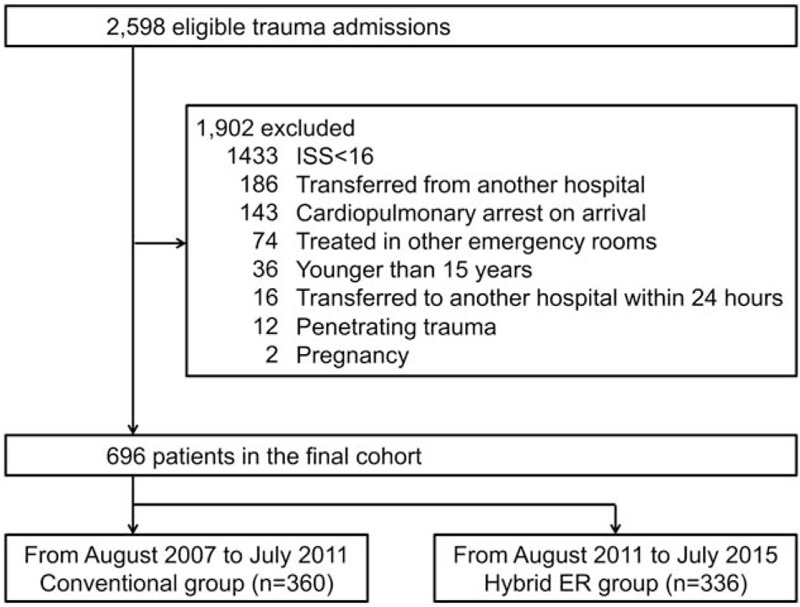

The study was conducted from August 2007 to July 2015 at the Osaka General Medical Center. We enrolled consecutive severe trauma patients [Injury Severity Score (ISS) ≥16], who were transferred directly from the scene of the incident to the trauma resuscitation room in our institution. Patients who were transferred from other hospitals and treated in other emergency rooms were excluded. Cases of traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest on arrival, pediatric patients younger than 15 years of age, patients who were transferred to other hospitals within 24 hours after admission, penetrating trauma patients, and pregnant women were excluded. The included population was divided into the Conventional group (from August 2007 to July 2011) and the Hybrid ER group (from August 2011 to July 2015) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patient flow diagram. ER indicates emergency room; ISS, Injury Severity Score.

Staff Composition

Our institution has been a tertiary referral hospital that includes an organization specialized in trauma management and intensive care. This trauma team consists of trauma surgeons, neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and intensivists. All trauma surgeons have been trained to perform not only general surgery but also IVR during their residency and fellowship in cooperation with radiologists. IVR was generally performed by the trauma surgeons and neurosurgeons unless specialized procedures, including aortic stenting, coronary intervention, and vascular recanalization were required.

Trauma Management in the Conventional Group

Our institution applied the Japan Advanced Trauma Evaluation and Care protocol, which was based on the ATLS concept.20 After completion of the primary survey, each attending trauma surgeon decided whether to transfer patients to the CT scanner located on the same floor as the emergency room. Hemodynamically stable patients or patients who rapidly responded to the initial fluid therapy were considered tolerable to CT scanning. All blunt trauma patients did not receive a selective CT, but a whole-body CT, including head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis unless a lesion of injury, was obvious from its mechanism. If certain abnormalities were clearly identified on FAST and radiography images, or patient transfer was difficult due to hemodynamic instability, an emergency bleeding control surgery was performed in the trauma resuscitation room. Patients underwent a CT scan after the operation. The time required to perform the CT scan, inclusive of the patient transfer time, was about 20 minutes.

Craniotomy, thoracotomy, and laparotomy were generally performed in an operation room. TAE was conducted in the angiography room, which was located next to the trauma resuscitation room.

Trauma Management in the Hybrid ER

The key concept of the trauma activation protocol in the Hybrid ER was immediate diagnosis with a whole-body CT and prompt surgical management for both head and trunk injuries. After transfer to the Hybrid ER, airway and breathing problems were fixed right away and circulatory abnormalities were assessed simultaneously. For patients who were in a state of shock, we first explored any signs of obstructive shock (cardiac tamponade or tension pneumothorax), and eliminated that. Apart from that, the attending physicians evaluated whether the patients could tolerate a few minutes of CT scanning; a systolic blood pressure (BP) of 70 mm Hg despite fluid resuscitation was regarded as the threshold. If CT scanning was judged to be acceptable, a whole-body CT scan was performed as with the conventional period even if the patient was in a shock status. If it was impossible to maintain a systolic BP of more than 70 mm Hg, an emergency resuscitative thoracotomy was performed. Damage control surgery, TAE, and a burr hole craniostomy were performed on the CT examination and intervention table (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, showing the IVR-CT system in the Hybrid ER), while the craniotomy and definitive surgery were performed in the operation room. No chest or pelvic radiographs were obtained during the initial trauma work-up.

Data Collection

The emergency department variables [Glasgow coma scale (GCS), systolic BP, heart rate (HR), shock index (SI), respiratory rate (RR), body temperature (BT), hemoglobin (Hb), pH, base excess (BE), lactate value, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR), and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT)] were recorded as the initial set of vital signs and laboratory tests. The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) of each body region was recorded, and the ISS, Revised Trauma Score (RTS), and probability of survival (Ps) were calculated using the Trauma and Injury Severity score (TRISS) (coefficients were b0 -1.2470, b1 0.9544, b2 -0.0768, and b3 -1.9052).21 Emergency procedures were recorded and categorized into the following groups: direct bleeding control surgery (thoracotomy, laparotomy, preperitoneal pelvic packing, and others), IVR (chest, abdomen, pelvis, and others), and intracranial surgery (burr hole craniostomy and craniotomy including craniectomy).

Outcome Measures

The primary endpoint of this study was defined as death in the hospital within 28 days of the injury. We set several secondary endpoints to evaluate the effectiveness of this system as written below. The cause of death was categorized into the following groups: exsanguination, traumatic brain injury (TBI), respiratory failure, sepsis, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and others. The 24-hour mortality, MODS (defined as Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score ≥2 points in ≥2 organ systems), as well as ventilator- and ICU-free days (within the first 28 days) were also evaluated. For patients who died within the first 28 days, “0” was allocated as the number of ventilator- and ICU-free days, even if the patients were once taken off the ventilator or discharged from the ICU. The length of hospital stay was also recorded and evaluated only in surviving patients. The Oxford Handicap Scale was evaluated at 28 days or the day of hospital discharge, whichever occurred first, and categorized into independent (Grade 0 to 2), dependent (Grade 3 to 5), or death. The total amount of administered crystalloid intravenous fluids, red blood cells (RBCs), fresh frozen plasmas (FFPs), and platelets concentrates (PCs) within the first 24 hours was calculated in the patients who survived more than 24 hours. The existence of trauma's lethal triad of hypothermia (BT <35°C), acidosis (pH <7.2), and coagulopathy (PT-INR > 1.5) was sequentially evaluated during the first 24 hours. The time duration from the patient arrival to the trauma resuscitation room to the beginning of the CT scanning and emergency surgery was measured.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables expressed as the median (25% and 75% percentiles) were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test because the data were not normally distributed. Categorical variables expressed as numbers (%) were compared by the Chi-square test unless the expected counts in any of the cells were below 5; Fisher exact test was used in this situation.

For the assessment of primary and secondary endpoints, we conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for clinically plausible or known confounders, including the mechanism of injury, HR, BT, Hb, lactate, PT-INR, and Ps. Furthermore, a simple logistic regression analysis and multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted only for Ps were performed. Finally, we constructed propensity score from 10 independent variables; 3 methods were used to confirm the robustness of our main results: covariate adjustment, stratification, and inverse probability of treatment weighting. The patient outcomes in the Hybrid ER group and Conventional group were evaluated on the basis of the estimated odds ratios (ORs) with its 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), where the Conventional group was set as a reference. As a sensitivity analysis, we evaluated the treatment-by-covariate interaction in the logistic regression analysis to explore the heterogeneity of the treatment effects across the subgroups: the SI on arrival (≥1 vs <1), Ps (<0.5 vs ≥0.5), bleeding control surgery (yes vs no), and intracranial surgery (yes vs no). The time point when the mortality began to decline was evaluated using a Ps adjusted logistic regression with Dunnett-Hsu adjustment and Ps adjusted natural cubic spline analysis with 7 knots located at the following years from the beginning of the operation of the Hybrid ER: -3, -2, and -1 year for the Conventional group, and 0, 1, 2, 3 years for the Hybrid ER group.

All reported P values were 2-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed with R software packages (version 3.1.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for Windows and SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Role of the Funding Source

No financial support was received for the performance of this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Of 2598 potentially eligible patients, 696 severe trauma patients were included for the analysis: 360 in the conventional group and 336 in the Hybrid ER group (Fig. 1). Table 1 summarizes patients’ baseline characteristics. There was a statistical difference in the mechanism of injury between the 2 groups. In addition, the PT-INR was higher in the Hybrid ER group than the Conventional group. Other than those, no significant differences were detected between the 2 groups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics on Arrival of the Patients Included

| Parameter | Conventional (n = 360) | Hybrid ER (n = 336) | P |

| Age, y | 49 (33−64) | 53 (36−66) | 0.11 |

| Sex | 0.97 | ||

| Male | 248 (69%) | 231 (69%) | |

| Female | 112 (31%) | 105 (31%) | |

| Mechanism of injury | 0.013 | ||

| Motor vehicle accident | 218 (61%) | 164 (49%) | |

| Fall from a height | 77 (21%) | 90 (27%) | |

| Fall down steps | 20 (6%) | 33 (10%) | |

| Ground level fall | 19 (5%) | 17 (5%) | |

| Crushed between objects | 11 (3%) | 7 (2%) | |

| Others | 15 (4%) | 25 (7%) | |

| GCS total score | 13 (7−14) | 13 (8−15) | 0.11 |

| HR, beats per min | 92 (78−109) | 91 (76−108) | 0.44 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 130 (103−154) | 133 (114−154) | 0.19 |

| Shock index ≥1 | 86 (24%) | 68 (20%) | 0.25 |

| RR, per min | 22 (19−28) | 21 (18−30) | 0.48 |

| BT, Celsius | 36.5 (35.8−36.8) | 36.5 (36.1−36.8) | 0.081 |

| RTS | 6.90 (5.97−7.84) | 7.33 (5.97−7.84) | 0.29 |

| Hb, g/dL | 13 (12−14) | 13 (12−14) | 0.47 |

| pH | 7.39 (7.33−7.42) | 7.40 (7.34−7.43) | 0.28 |

| Base excess, mmol/L | -1.5 (-4.3 to 0.6) | -1.7 (-4.5 to 0.3) | 0.25 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 2.5 (1.7−3.8) | 2.4 (1.5−3.7) | 0.26 |

| PT-INR | 1.10 (1.00−1.20) | 1.10 (1.00−1.23) | <0.0001 |

| APTT, s | 30 (27−35) | 30 (27−38) | 0.92 |

| AIS Head ≥3 | 254 (71%) | 232 (69%) | 0.67 |

| AIS Face ≥3 | 4 (1%) | 7 (2%) | 0.30 |

| AIS Chest ≥3 | 193 (54%) | 175 (52%) | 0.69 |

| AIS Abdomen ≥3 | 70 (19%) | 65 (19%) | 0.97 |

| AIS Extremities ≥3 | 115 (32%) | 126 (38%) | 0.12 |

| Injury Severity Score | 26 (21−35) | 26 (21−38) | 0.35 |

| Probability of survival | 0.91 (0.68−0.97) | 0.91 (0.68−0.97) | 0.54 |

Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (%), and continuous variables are presented as medians (25−75 percentiles).

AIS indicates Abbreviated Injury Scale; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; BP, blood pressure; BT, body temperature; ER, emergency room; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; Hb, hemoglobin; HR, heart rate; PT-INR, prothrombin time international normalized ratio; RR, respiratory rate; RTS, Revised Trauma Score.

Interventions

There was no significant difference in the ratio of patients who received emergency bleeding control procedures between the 2 groups [Conventional 87 (24%) vs Hybrid ER 92 (27%); P = 0.33]; however, the patients in the Hybrid ER group received IVR more frequently than those in the Conventional group [Conventional 62 (17%) vs Hybrid ER 82 (24%); P = 0.019 (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, showing the interventions performed in each group]. On the contrary, the ratio of patients who underwent intracranial surgery was significantly higher in the Conventional group [Conventional 107 (30%) vs Hybrid ER 74 (22%); P = 0.020]. The ratio of patients who received emergency surgery before or without CT in the Conventional group was higher than that of the Hybrid ER group [Conventional 13 (4%) vs Hybrid ER 1 (0%); P = 0.002].

Effects on Mortality

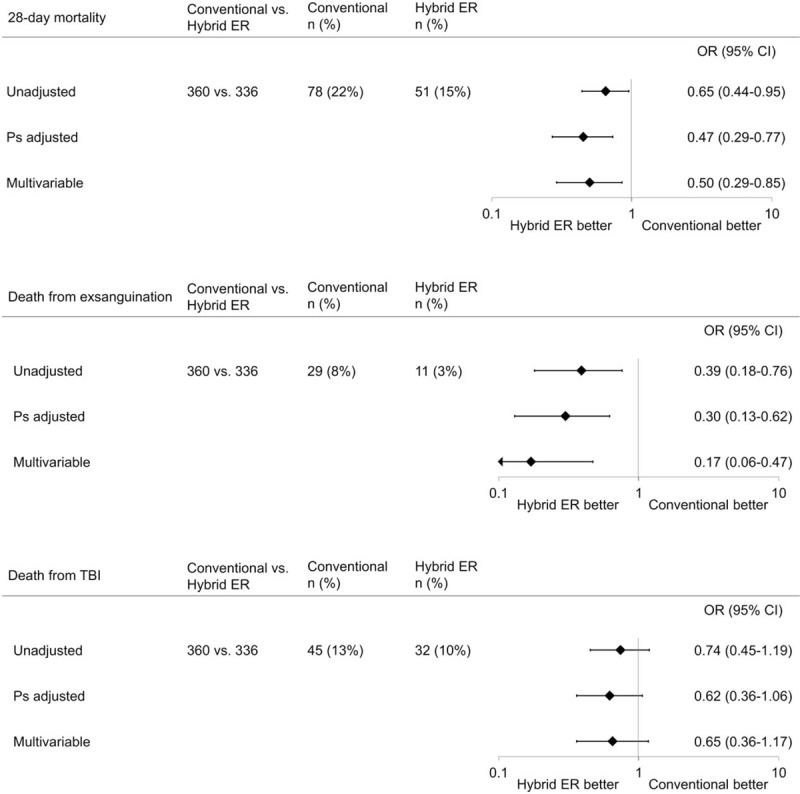

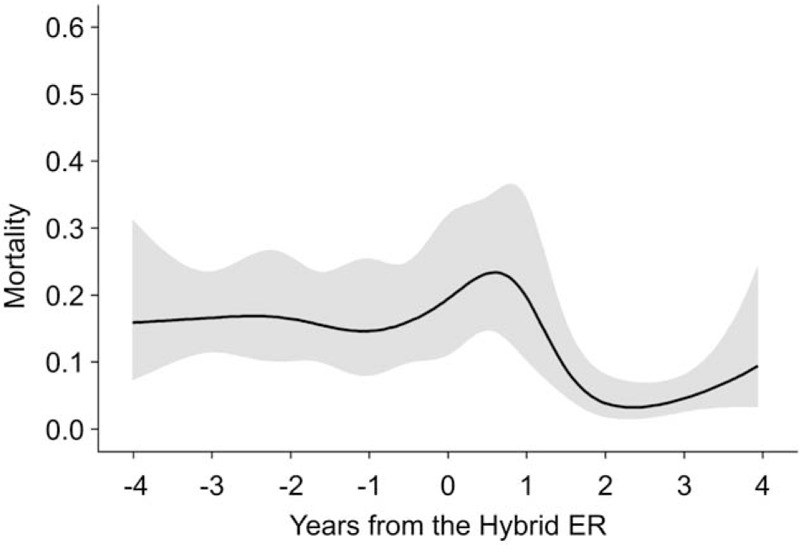

Compared with the Conventional group, the 28-day mortality was significantly lower in the Hybrid ER group (Table 2). After adjusting for confounders by multivariable logistic regression analysis, a significant association between the Hybrid ER group and reduced 28-day mortality was observed (Fig. 2). This association was not materially affected by the other models: a simple logistic regression analysis and multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted only for Ps. Propensity score analyses also confirmed the robustness of the above results. Furthermore, the Hybrid ER group was significantly associated with a reduced number of deaths from exsanguination. However, there was no significant association between the Hybrid ER group and death from TBI. Only a small number of patients died from the causes except exsanguination or TBI in both groups. The subgroup analyses according to the SI on arrival (≥1 vs < 1), Ps (<0.5 vs ≥0.5), bleeding control surgery (yes vs no), and intracranial surgery (yes vs no) showed no significant ORs (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, showing all-cause mortality by subgroups). Compared with the Conventional group, the 28-day mortality was significantly lower in the Hybrid ER group over 2 to 3 and 3 to 4 years (adjusted OR, 0.22 and 0.25; adjusted 95% CI, 0.07–0.69 and 0.08–0.80; adjusted P = 0.004 and 0.012, respectively), but was insignificant during 0 to 1 and 1 to 2 years (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 4, showing Ps adjusted 28-day mortality for each year of the Hybrid ER period). The 28-day mortality tended to decline over 1 to 2 years (Fig. 3).

TABLE 2.

Overall Mortality and Adjudicated Cause of Death by the Period From Admission

| Conventional (n = 360) | Hybrid ER (n = 336) | P | |

| 24-h mortality | 49 (14%) | 31 (9%) | 0.070 |

| Exsanguination | 29 (8%) | 11 (3%) | 0.007 |

| TBI | 20 (6%) | 18 (5%) | 0.91 |

| MODS | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Sepsis | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Respiratory | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 0.23 |

| Others | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 28-day mortality | 78 (22%) | 51 (15%) | 0.028 |

| Exsanguination | 29 (8%) | 11 (3%) | 0.007 |

| TBI | 45 (13%) | 32 (10%) | 0.21 |

| MODS | 4 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 0.37 |

| Sepsis | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 0.23 |

| Respiratory | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 0.23 |

| Others | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | 0.11 |

Data are expressed as numbers (%).

ER indicates emergency room; MODS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

FIGURE 2.

Effects on the 28-day mortality, death from exsanguination, and death from TBI. Odds ratios with 95% confidence interval plots showing the association of the treatment group with the 28-day mortality, death from exsanguination, and death from TBI were expressed. Three models of logistic regression analyses were performed for the assessment of each outcome. “Unadjusted” stands for the simple logistic regression, “Ps adjusted” stands for multivariable logistic regression adjusted only for Ps, and “Multivariable” stands for multivariable logistic regression adjusted for the mechanism of injury, HR, BT, Hb, lactate, PT-INR, and Ps. Odds ratios are plotted on base-10 logarithmic scales. BT indicates body temperature; CI, confidence interval; ER, emergency room; HR, heart rate; OR, odds ratio; Ps, probability of survival; PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

FIGURE 3.

Ps adjusted 28-day mortality and its 95% point-wise confidence interval associated with the years from the Hybrid ER. The restricted cubic spline curve was expressed at Ps = 0.78, which was the average Ps of the Conventional group. ER indicates emergency room; Ps, probability of survival.

Secondary Endpoints

A significantly larger number of patients in the Hybrid ER group was classified as independent at discharge or by 28 days than those in the Conventional group (Table 3). The total amount of the fluid administration within the first 24 hours was smaller in the Hybrid ER group; however, the units of blood products transfused did not differ significantly between the 2 groups.

TABLE 3.

Secondary Endpoints

| Conventional (n = 360) | Hybrid ER (n = 336) | P | |

| Oxford handicapped scale | 0.001 | ||

| Independent | 117 (33%) | 153 (46%) | |

| Dependent | 165 (46%) | 132 (39%) | |

| Death | 78 (22%) | 51 (15%) | |

| MODS | 157 (44%) | 141 (42%) | 0.66 |

| Ventilator-free days, d | 21 (6−28) | 22 (12−28) | 0.094 |

| ICU-free days, d | 14 (0−21) | 15 (2−23) | 0.017 |

| Hospital stay, d | 32 (17–64) | 35 (19–64) | 0.23 |

| Fluid administration within 24 h, L | 7.6 (5.3−10.8) | 6.2 (4.2−10.8) | 0.011 |

| RBC administration within 24 h, Unit | 0 (0−4) | 0 (0−4) | 0.18 |

| FFP administration within 24 h, Unit | 0 (0−0) | 0 (0−0) | 0.26 |

| PC administration within 24 h, Unit | 0 (0−0) | 0 (0−0) | 0.27 |

| Deadly triad ≥1 | 78 (22%) | 58 (17%) | 0.14 |

| Hypothermia: BT <35°C | 45 (13%) | 28 (8%) | 0.073 |

| Acidosis: pH <7.2 | 37 (10%) | 35 (10%) | 0.95 |

| Coagulopathy: PT-INR >1.5 | 7 (2%) | 18 (5%) | 0.016 |

Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (%), and continuous variables are presented as medians (25−75 percentiles). The Oxford Handicap Scale was evaluated at 28 days or the day of hospital discharge, whichever occurred first, and categorized into independent (Grade 0–2), dependent (Grade 3–5), or death. Both ventilator- and ICU-free days were evaluated within the first 28 days.

BT indicates body temperature; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; ICU, intensive care unit; MODS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; PC, platelets concentrate; PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio; RBC, red blood cell.

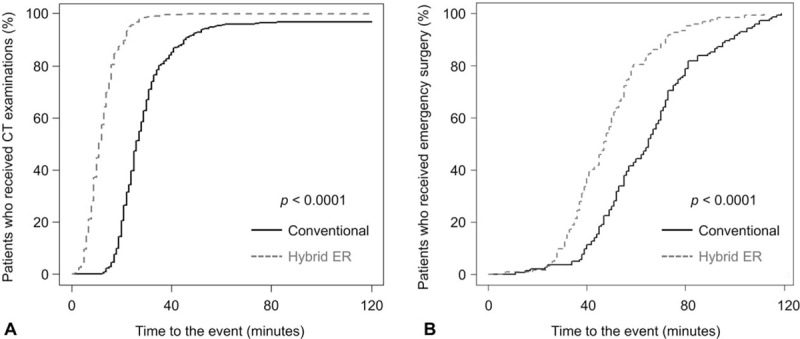

Time Course

The time intervals from the arrival to the trauma resuscitation room to the beginning of the CT scanning [Conventional 26 (21 to 32) minutes vs Hybrid ER 11 (8 to 16) minutes; P < 0.0001] and to the beginning of the emergency surgery [Conventional 68 (51 to 85) minutes vs Hybrid ER 47 (37 to 57) minutes; P < 0.0001] were both shorter in the Hybrid ER group (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 5, showing time course). Moreover, the time to initiate IVR apart from direct surgery was also significantly reduced in the Hybrid ER group. Log rank tests showed significant differences both in the time required to start the CT scanning and the time required to start the emergency procedure (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan-Meier curve relating treatment group to time to start (A) CT and (B) emergency procedure. CT indicates computed tomography; ER, emergency room.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that the novel trauma workflow, using the Hybrid ER, was associated with a reduced 28-day mortality in patients with severe trauma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has reported the effectiveness of the trauma workflow, with the installation of IVR-CT in the trauma resuscitation room, for the clinical outcomes.

Several retrospective studies have reported the efficacy of a whole-body CT, during trauma resuscitation, for decreasing the mortality. Huber-Wagner et al22 reported that the recorded mortality rate was significantly lower than the predicted mortality for patients who underwent a whole-body CT. On the contrary, there was no significant difference between the recorded and predicted mortalities in patients who did not undergo a whole-body CT.22 A recent randomized control trial showed no significant differences in the in-hospital mortality between the immediate total-body CT group and the standard work-up group, through conventional imaging supplemented by selective CT.23 It should be noted that this trial had several limitations; however, the advantage of a whole-body CT over a standard work-up in patients suspected of having severe trauma has not been well-demonstrated thus far.

The major difference between the previous trials and our study is that we did not focus on diagnosis protocols; we evaluated the effectiveness of the entire trauma workflow with the installation of IVR-CT in the trauma resuscitation room. This suggested that it is not the whole-body CT, during the initial diagnostic work-up, but the novel trauma workflow—comprised of an immediate CT examination, damage control surgery, and IVR without any patient transfer—that contributed to the improved mortality. The system enabled us to initiate CT scanning and emergency procedures in a shorter amount of time. Thus, we could perform the emergency procedures promptly with sophisticated information on the bleeding site provided by the CT examination. This might have been of critical importance in the case of severe trauma patients who had a life-threatening hemorrhage; the Hybrid ER group was strongly associated with a decrease in number of deaths from exsanguination. These results were consistent with a recent study that showed that the close location of CT equipment to the trauma resuscitation room was associated with a reduction in the time required to start the CT and, thereby, improve the mortality.12 We believe this trauma workflow—that completes all emergency examinations and life-saving procedures in the trauma resuscitation room without transportation—is the ideal method of resuscitation in patients with life-threatening injuries.

There are several advancements in our practice that arose from developments in the equipment. A significantly higher proportion of patients received IVR in the Hybrid ER group than in the Conventional group. This difference suggested that existence of the IVR-CT system in the trauma resuscitation room improved access to angiography and expanded the indication of IVR. The time to start IVR in the Hybrid ER period [48 (35 to 56) minutes] was greatly shorter than that in a recent observational study [286 (210 to 378) minutes] in the United States, as well as the Conventional period [73 (52 to 95) minutes].24 A possible explanation of this result is that all trauma surgeons in our institute were trained to perform IVR and we did not have to wait for a radiologist. Thus, encouraging trauma surgeons to perform IVR may create a breakthrough and lead to the progress of trauma workflow in the near future.

There are important limitations to consider when interpreting the decreased mortality in the Hybrid ER group. First, several potential biases exist because of the retrospective study design. As it was ethically difficult to include a control arm in the Hybrid ER period, we set the Conventional group as the control. However, we tried our best to adjust for any clinically important confounders and observed a robust association between the treatment group and mortality. Second, there could be several differences in concomitant standards of care. Representative imbalances include emergence of permissive hypotension concepts, application of early blood transfusion, and changes in physician staffing. Third, the reason why the ratio of intracranial surgery decreased in the Hybrid ER group was not clear. As both GCS score and the ratio of patients who had head AIS score of 5 were similar between the groups, this difference was considered not to be extracted from the baseline imbalances. However, the effectiveness of the Hybrid ER system in patients with severe TBI should be evaluated independently. Fourth, we could not demonstrate the appropriate target for the treatment in the Hybrid ER. We only analyzed severe trauma with an ISS ≥16; however, this cannot be estimated before the patient's arrival to the trauma resuscitation room. Finally, we could not calculate costs of medical care from records in the 2 periods. Although the reduced proportion of disabled patients and increased ICU-free days in the Hybrid ER group suggested potential cost savings, the actual cost-effectiveness of the Hybrid ER should be investigated separately.

CONCLUSION

We reported that a novel trauma workflow using the Hybrid ER was associated with a decreased mortality in cases with severe trauma. These results were founded on the basis of a reduction in the number of deaths from exsanguination, as a consequence of a reduction in the time required for the diagnosis and treatment. We believe that the combination of an immediate and precise diagnosis by a whole-body CT and rapid bleeding control without transferring the patient will bring progress in trauma management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank all the doctors and nurses of the Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care at the Osaka General Medical Center.

Footnotes

TK conceived, designed, and coordinated the study, performed the data acquisition and analyses, and drafted the manuscript. KY participated in the data interpretation and helped to draft the manuscript. TH and KO performed the statistical analysis. HM, YY, DW, and YN contributed to the data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. SF exerted a major impact on the interpretation of the data and critical appraisal of the manuscript.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

The enthusiasm and work put into the operation of the Hybrid ER system by Naoki Nakamoto, Yuri Shimoikeda, Kenta Nishi, and Naoki Fujie have made this clinical trial possible.

We do not require reprints of the manuscript.

No financial support was received for the performance of this study.

The authors have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. ATLS Advanced Trauma Life Support Program for Doctors. Student Course Manual, 9th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deunk J, Dekker HM, Brink M, et al. The value of indicated computed tomography scan of the chest and abdomen in addition to the conventional radiologic work-up for blunt trauma patients. J Trauma 2007; 63:757–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mistral T, Brenckmann V, Sanders L, et al. Clinical judgment is not reliable for reducing whole-body computed tomography scanning after isolated high-energy blunt trauma. Anesthesiology 2017; 126:1116–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langdorf MI, Medak AJ, Hendey GW, et al. Prevalence and clinical import of thoracic injury identified by chest computed tomography but not chest radiography in blunt trauma: multicenter prospective cohort study. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 66:589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rieger M, Czermak B, El Attal R, et al. Initial clinical experience with a 64-MDCT whole-body scanner in an emergency department: better time management and diagnostic quality? J Trauma 2009; 66:648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilbert P, zur Nieden K, Hofmann GO, et al. New aspects in the emergency room management of critically injured patients: a multi-slice CT-oriented care algorithm. Injury 2007; 38:552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wurmb TE, Frühwald P, Hopfner W, et al. Whole-body multislice computed tomography as the first line diagnostic tool in patients with multiple injuries: the focus on time. J Trauma 2009; 66:658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saltzherr TP, Bakker FC, Beenen LF, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing the effect of computed tomography in the trauma room versus the radiology department on injury outcomes. Br J Surg 2012; 99 Suppl 1:105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weninger P, Mauritz W, Fridrich P, et al. Emergency room management of patients with blunt major trauma: evaluation of the multislice computed tomography protocol exemplified by an urban trauma center. J Trauma 2007; 62:584–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fung Kon Jin PH, Goslings JC, Ponsen KJ, et al. Assessment of a new trauma workflow concept implementing a sliding CT scanner in the trauma room: the effect on workup times. J Trauma 2008; 64:1320–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KL, Graham CA, Lam JM, et al. Impact on trauma patient management of installing a computed tomography scanner in the emergency department. Injury 2009; 40:873–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber-Wagner S, Mand C, Ruchholtz S, et al. Effect of the localisation of the CT scanner during trauma resuscitation on survival: a retrospective, multicentre study. Injury 2014; 45:S76–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stassen NA, Bhullar I, Cheng JD, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt hepatic injury: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 73:S288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stassen NA, Bhullar I, Cheng JD, et al. Selective nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 73:S294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papakostidis C, Kanakaris N, Dimitriou R, et al. The role of arterial embolization in controlling pelvic fracture haemorrhage: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81:897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes J, Scrimshire A, Steinberg L, et al. Interventional Radiology service provision and practice for the management of traumatic splenic injury across the Regional Trauma Networks of England. Injury 2017; 48:1031–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misselbeck TS, Teicher EJ, Cipolle MD, et al. Hepatic angioembolization in trauma patients: indications and complications. J Trauma 2009; 67:769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juern JS, Milia D, Codner P, et al. Clinical significance of computed tomography contrast extravasation in blunt trauma patients with a pelvic fracture. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017; 82:138–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wada D, Nakamori Y, Yamakawa K, et al. First clinical experience with IVR-CT system in the emergency room: positive impact on trauma workflow. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2012; 20:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee of the Japan Association of Traumatology. The Japan Advanced Trauma Evaluation and Care (JATEC). 5th ed. Tokyo: Herusu Shuppan Co, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Champion HR, Copes WS, Sacco WJ, et al. The Major Trauma Outcome Study: establishing national norms for trauma care. J Trauma 1990; 30:1356–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber-Wagner S, Lefering R, Qvick LM, et al. Effect of whole-body CT during trauma resuscitation on survival: a retrospective, multicentre study. Lancet 2009; 373:1455–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sierink JC, Treskes K, Edwards MJ, et al. Immediate total-body CT scanning versus conventional imaging and selective CT scanning in patients with severe trauma (REACT-2): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 388:673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tesoriero RB, Bruns BR, Narayan M, et al. Angiographic embolization for hemorrhage following pelvic fracture: is it “time” for a paradigm shift? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017; 82:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.