Abstract

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a potentially lethal syndrome, which is characterized by an acute deterioration of liver function in patients with chronic liver diseases. The present paper reported that an alcoholic cirrhotic patient with ACLF developed septic shock, hydrothorax, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, acute kidney injury, and acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding at the same hospitalization and was successfully rescued by pharmacotherapy alone without any invasive intervention.

Key words: acute-on-chronic liver failure, liver cirrhosis, organ failure, bleeding, pharmacotherapy

Introduction

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) refers to an acute deterioration of liver dysfunction in patients with chronic liver diseases or liver cirrhosis. It has a dismal prognosis with 28-day mortality rate of ≥ 15%.[1] ACLF may occur in the setting of infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, and alcoholic hepatitis.[2, 3] Major clinical presentations include sepsis, renal failure, and hepatic encephalopathy. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver proposed and updated the diagnostic criteria for ACLF in 2009 and 2014, respectively (i.e., serum bilirubin ≥ 5 mg/ dl or 85 mmol/L and coagulopathy, defined as international normalized ratio (INR) ≥ 1.5 or prothrombin activity < 40%, complicated by ascites and/or hepatic encephalopathy within 4 weeks in patients who were previously diagnosed or undiagnosed with chronic liver diseases).[4, 5] European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium also proposed the definition of ACLF in 2013 according to the presence and number of organ failures, including liver, kidney, cerebral, coagulation, circulation, and respiratory failure.[6] Regardless, early recognition and supportive intensive care are essential for the prevention of irreversible organ failures.[7]

Herein, we reported that a cirrhotic patient with ACLF developed multiple acute decompensation events during his hospitalization and was successfully rescued by pharmacotherapy alone.

Case presentation

On January 18, 2018, a 49-year-old male presented with fever, chills, and diarrhea at the Department of Emergency of our hospital. His highest temperature was 40 °C. He had a history of acute pancreatitis and fatty liver 3 years ago. He had been diagnosed with liver cirrhosis and mild ascites at the first time in December, 2017 and underwent esophageal variceal ligation for acute variceal bleeding at our department on January 2, 2018. He had drunk wine 0.5 kg/day for more than 10 years. On physical examinations, he was intermittently seditious, confused, and disoriented, his skin was yellowish, shifting dullness was positive, and lower limb edema was moderate. His body temperature was 38.7 °C, heart rate was 100 beats per minute, and blood pressure (BP) was 100/54 mmHg. Laboratory tests revealed that white blood cell (WBC) was 6.0 × 109/L (reference range: 3.5–9.5 ×109/L), neutrophilic granulocyte percentage (GR%) was 68.5% (reference range: 40-75%), hemoglobin (Hb) was 69 g/ L (reference range: 130–175 g/L), total bilirubin (TBIL) was 126.8 μmol/L (reference range: 5.1–22.2 μmol/L), direct bilirubin (DBIL) was 61.5 μmol/L (reference range: 0–8.6 μmol/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 37.39 U/L (reference range: 9-50 U/ L), aspartate aminotransaminase (AST) was 54.7 U/ L (reference range: 15–40 U/ L), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GGT) was 72.05 U/L (reference range: 10–60 U/L), albumin (ALB) was 29 g/ L (reference range: 40–55 g/ L), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was 9.77 mmol/ L (reference range: 2.9-8.2 mmol/L), creatinine (Cr) was 67.8 μmol/L (44-133 μmol/L), prothrombin time (PT) was 30.7 s (reference range: 11.5–14.5 s), INR was 2.90, procalcitonin was 25.24 ng/mL (reference range: 0–0.05 ng/mL), PaO2 was 79 mmHg, and FiO2 was 29.0%. Chest and abdomen computed tomography demonstrated pneumonia, hydrothorax, liver cirrhosis, splenomegaly, cholecystitis, ascites, and right renal calculus. Thus, a diagnosis of ACLF grade 1 secondary to infection was considered (Table 1). Child-Pugh score was 12 and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was 25.4. He was treated with ademetionine for liver dysfunction, L-Ornithine-L-Aspartate for hepatic encephalopathy, montmorillonite powder and bifidobacterium lactobacillus tripterygium for diarrhea, and ceftriaxone sodium for infection.

Table 1.

Progression and remission of ACLF in this patient according to the criteria of CLIF-SOFA (Chronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Assessment)

| Organ failure | 18-Jan | 19-Jan | 31-Jan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 7.4 | 8.1 | 8.7 |

| (bilirubin > 12 mg/dL) | |||

| Kidney | 0.76 | 1.62 | 0.61 |

| (creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL) | |||

| Cerebal | II | II | No |

| (grade III-IV West-Haven classification) | |||

| Coagulation | 3.25 | 2.9 | 2.89 |

| (INR > 2.5 and/or a platelet count of 20 × 109/L) | |||

| Circulation | No | Dopamine and terlipression | No |

| (use of dopamine, dobutamine, or terlipressin) | |||

| Respiratory | 272 | NA | NA |

| (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 or SpO2/FiO2 ≤ 200) | |||

| Grade | ACLF grade 1 | ACLF grade 2 | No ACLF |

INR: international normalized ratio; ACLF: acute-on-chronic liver failure; NA: not available

At 12 o’clock on January 19, 2018, the patient was still febrile, the temperature was up to 38.5 °C, BP was 59/23 mmHg and heart rate was 110 beats per minute. He was oliguria with a total of 200 mL urine drained from urethral catheter during the past 24 hours. Septic shock was considered. Blood culture findings revealed the presence of epidermal staphylococcus and gram-positive bacteria. Laboratory tests indicated that WBC was 9.9 × 109/L, GR% was 84.4%, Hb was 63 g/ L, TBIL was 138.6 μmol/L, DBIL was 85.5 μmol/L, AST was 40.51 U/L, γ-GGT was 63.38 U/L, BUN was 15.76 mmol/L, Cr was 143.56 μmol/L, PT was 33.6 s, and INR was 3.25. Acute kidney injury (AKI) stage 2 was considered. ACLF grade 2 was also diagnosed (Table 1). Red blood cells were transfused; dopamine, meropenem, and terlipressin were intravenously infused.

At 19 o’clock on January 19, 2018 and 2 o’clock on January 20, 2018, the patient developed hematemesis twice with a total of 450 mL dark red colored blood vomited. Esomeprazole, somatostatin, and human albumin were intravenously infused except for nutritional support. On January 21, 2018, the patient became stable, his BP was 86/57 mmHg, heart rate was 110 beats per minute, and body temperature was 37 °C. Laboratory tests were as follows: WBC was 5.4 × 109/L, GR% was 78.4%, Hb was 94 g/L, TBIL was 155.9 μmol/L, DBIL was 90.4 μmol/L, AST was 32.52 U/L, γ-GGT was 52.3 U/L, BUN was 10.27 mmol/L, and Cr was 42.04 μmol/L.

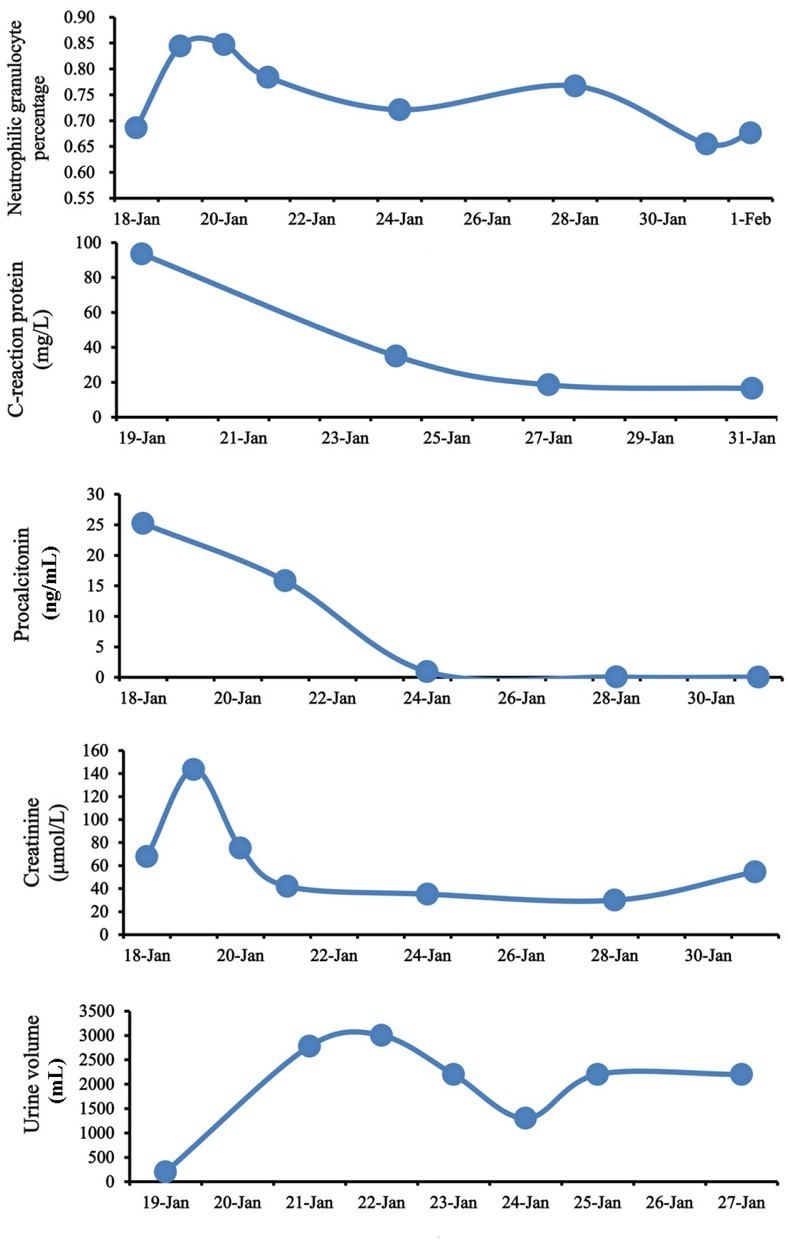

After that, GR%, C-reaction protein, procalcitonin, Cr, and urine volume gradually improved (Figure 1). He did not develop hematemesis or melena. On January 31, 2018, fecal occult blood test was negative; other laboratory tests showed that WBC was 11.1 × 109/L, GR% was 65.5%, Hb was 84 g/L, Cr was 54.56 μmol/L, C-reaction protein was 16.5 mg/L (reference range: 0–8 mg/L), and

Figure 1.

Dynamic changes of neutrophilic granulocyte percentage, C-reaction protein, procalcitonin, creatinine, and urine volume during the hospitalization.

procalcitonin was 0.03 ng/mL. At that time, he did not have ACLF (Table 1). Then, the patient was discharged.

On April 9, 2018, the patient presented with mild distension of abdomen and mild lower limb edema at our department and underwent follow-up laboratory tests. Hb was 87 g/ L, TBIL was 77.4 μmol/L, DBIL was 40.9 μmol/L, AST was 54.77 U/L, ALT was 28.05 U/L, γ-GGT was 61.07 U/L, ALB was 30.6 g/L, BUN was 5.36 mmol/L, Cr was 36.79 μmol/L, PT was 19.7 s, and INR was 1.67. Furosemide and spironolactone were prescribed for the management of ascites.

Discussion

ACLF often has a high short-term mortality in patients with cirrhosis due to the appearance of organ failure,[2, 8] which is always associated with a rapid and exaggerated activation of systemic inflammation.[9] Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is defined by the presence of two or more of the following components: temperature > 38 °C or < 36 °C; heart rate > 90 beats per minute; respiratory rate > 20 breaths per minute or PaCO2 < 32 mmHg; WBC < 4 × 109/L or > 12 × 109/L.[10] Except for SIRS, this

patient further developed a mean arterial blood pressure of ≤ 65 mmHg, suggesting the development of septic shock.[11] Generally, except for prompt settlement of suspected or certain infection, the treatment strategy of septic shock contains immediate intravenous access, fluid administration, vasopressors, and care directing at restoring adequate circulation.[11] In our case, at our admission when SIRS was diagnosed, ceftriaxone sodium was the first-line antibiotics. He rapidly developed septic shock after 1 hour. Thus, meropenem (3 g intravenous infusion per day for 5 days) was selected, which is a drug of empirical treatment for severe septic shock. It is a broad-spectrum antibiotic covering gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria, and anaerobic bacteria.[12] Infection was successfully and effectively controlled. Indeed, our blood culture findings confirmed the presence of epidermal staphylococcus and gram-positive bacteria, which was sensitive to meropenem.

Renal dysfunction is one of the most common organ failures in patients with ACLF[13] and is closely related to the presence of bacterial infection and hypovolemia.[14, 15] Our case had an increase of Cr from 67.8 μmol/L to 143.67μmol/L, suggesting the development of AKI stage 2.[16] Additionally, our case also had cirrhosis and ascites without current or recent use of nephrotoxic drugs or macroscopic signs of structural kidney injury. The first-line treatment is terlipressin in combination with human albumin.[17] Recent evidence suggested that continuous intravenous infusion of terlipressin be better tolerated than intravenous boluses.[18] Our case received continuous intravenous infusion terlipressin in combination with human albumin and achieved a complete response that his Cr was significantly decreased.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is another decompensation event developing in this cirrhotic patient. Considering that he had a Child-Pugh class C and a MELD score of 25.4, the in-hospital mortality of this patient should be very high.[19, 20] Our case had undergone endoscopic therapy for the management of gastroesophageal variceal bleeding before this admission. At this admission, an endoscopic therapy was refused due to his poor status. However, pharmacotherapy with vasoconstrictors is successful for controlling acute bleeding event.

In conclusion, we presented a case with ACLF developing multiple acute decompensation events, which were effectively alleviated by conservative treatment. Certainly, early recognition and intervention should be also emphasized.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

Financial support None.

References

- 1.Blasco-Algora S, Masegosa-Ataz J, Gutierrez-Garcia ML, Alonso-Lopez S, Fernandez-Rodriguez CM. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Pathogenesis, prognostic factors and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12125–40. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jalan R, Williams R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: pathophysiological basis of therapeutic options. Blood Purif. 2002;20:252–61. doi: 10.1159/000047017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreau R, Arroyo V. Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: A New Clinical Entity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:836–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Fan ST, Garg H. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL) Hepatol Int. 2009;3:269–82. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarin SK, Kedarisetty CK, Abbas Z, Amarapurkar D, Bihari C, Chan AC. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) Hepatol Int 2014; 2014;8:453–71. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim TY, Kim DJ. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013;19:349–59. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2013.19.4.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asrani SK, Simonetto DA, Kamath PS. Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2128–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng Y, Qi X, Tang S, Deng H, Li J, Ning Z. Child-Pugh, MELD, and ALBI scores for predicting the in-hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10:971–80. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2016.1177788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasmuth HE, Kunz D, Yagmur E, Timmer-Stranghöner A, Vidacek D, Siewert E. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure display “sepsis-like” immune paralysis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Indian J Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seymour CW, Rosengart MR. Septic Shock: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2015;314:708–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiseman LR, Wagstaff AJ, Brogden RN, Bryson HM. Meropenem. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy. Drugs. 1995;50:73–101. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199550010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson JC, Wendon JA, Kramer DJ, Arroyo V, Jalan R, Garcia-Tsao G. Intensive care of the patient with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1864–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.24622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martín-Llahí M, Guevara M, Torre A, Fagundes C, Restuccia T, Gilabert R. Prognostic importance of the cause of renal failure in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:488–96. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.043. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alam A, Chun Suen K, Ma D. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: recent update. J Biomed Res. 2017;31:283–300. doi: 10.7555/JBR.30.20160060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angeli P, Gines P, Wong F, Bernardi M, Boyer TD, Gerbes A. Diagnosis and management of acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: revised consensus recommendations of the International Club of Ascites. Gut. 2015;64:531–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pericleous M, Sarnowski A, Moore A, Fijten R, Zaman M. The clinical management of abdominal ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome: a review of current guidelines and recommendations. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:e10–8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavallin M, Piano S, Romano A, Fasolato S, Frigo AC, Benetti G. Terlipressin given by continuous intravenous infusion versus intravenous boluses in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: A randomized controlled study. Hepatology. 2016;63:983–92. doi: 10.1002/hep.28396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng Y, Qi X, Dai J, Li H, Guo X. Child-Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the in-hospital mortality of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:751–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng Y, Qi X, Guo X. Child-Pugh Versus MELD Score for the Assessment of Prognosis in Liver Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Medicine. 2016;95:e2877. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]