Abstract

Background

Remifentanil is widely used for ultrasound-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of small hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We determined whether dexmedetomidine could be an alternative to remifentanil for RFA of HCC under general anesthesia with sevoflurane.

Methods

We prospectively randomized patients scheduled to undergo RFA for HCC to a dexmedetomidine (DEX) group or remifentanil (REMI) group (47 patients each). In the DEX group, a bolus infusion (0.4 μg kg− 1) was started 15 min before anesthesia induction and continued at 0.2 μg kg− 1 h− 1 until 10 min before the end of surgery. In the REMI group, 3 μg kg− 1 h− 1 of remifentanil was administered from 15 min before anesthesia induction to the end of the surgery. The primary endpoint was postoperative pain intensity. Secondary endpoints included analgesic requirement, postoperative liver function, patient comfort, and hemodynamic changes. Group allocation was concealed from patients and data analysts but not from anesthesiologists.

Results

Postoperative pain intensity, analgesic consumption, comfort, liver function, and time to emergence and extubation did not differ between the two groups. Heart rate, but not mean arterial pressure, was significantly lower in the DEX group than in the REMI group, at 1 min after intubation and from 30 min after the start of the surgery until anesthesia recovery. Sevoflurane concentration and dosage were significantly lower in the DEX group than in the REMI group.

Conclusion

During RFA for HCC, low-dose dexmedetomidine reduced the heart rate and need for inhalational anesthetics, without exacerbating postoperative discomfort or liver dysfunction. Although it did not exhibit outstanding advantages over remifentanil in terms of pain management, dexmedetomidine could be a safe alternative adjuvant for RFA under sevoflurane anesthesia.

Trial registration

Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, ChiCTR-OPC-15006613. Registered on 16 June 2015.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13063-018-3010-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Catheter ablation, Dexmedetomidine, Pain measurement

Background

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is one of the most effective treatments for small hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) [1, 2]. RFA achieves complete ablation in 90–95% cases of small HCCs, with 5- and 10-year survival rates comparable to those after surgery [3–6]. Owing to its superior tumor control, high survival rates, minimally invasive nature, and ease of use, RFA has become the first-line treatment for small HCCs, especially in patients who are not eligible for surgical resection or liver transplantation [7, 8]. Percutaneous RFA can be performed under sedation, local anesthesia, or general anesthesia. However, some patients experience severe pain and anxiety during RFA under local anesthesia, which results in lower patient satisfaction and insufficient tumor ablation [9]. General anesthesia provides better pain control, better tolerance, and lower local recurrence rates [10].

Remifentanil, an ultra-short-acting μ-opioid-receptor agonist, has been demonstrated to be safe and reliable for RFA [11, 12]. As an adjuvant drug, remifentanil provides continuous analgesia and stable hemodynamics, but can cause cardiovascular side effects such as bradycardia, atrioventricular or sinoatrial block, and hypotension [13]. Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2-adrenoreceptor agonist with sedative, anxiolytic, and analgesic effects [14, 15]. It also exhibits neuroprotective properties [16], anti-inflammatory benefits [17], and protective effects on the myocardium [18], against ischemia or reperfusion in the brain [19], and against lung [20], kidney [21], and liver injuries [22, 23]. In patients undergoing percutaneous RFA of small HCCs under general anesthesia with sevoflurane, it is unclear whether dexmedetomidine exhibits outstanding advantages over remifentanil in terms of pain management, or if it could be an alternative to remifentanil.

Thus, the purpose of this prospective randomized study was to compare the effects of dexmedetomidine and remifentanil on postoperative pain intensity, analgesic requirements, liver function, and general comfort in patients undergoing RFA of HCCs under general anesthesia with sevoflurane.

Methods

Ethics

Ethical approval for this randomized prospective controlled study was provided by the ethics committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat Sen University, Guangzhou, China, on 5 May 2015. This study was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-OPC-15006613, http://www.chictr.org.cn/edit.aspx?pid=11243&htm=4) on 16 June 2015. The checklist from the CONSORT 2010 Statement was used (Additional file 1).

Patients and selection criteria

The study involved patients who were scheduled to undergo elective RFA for HCC under general anesthesia in our hospital between June 2015 and October 2015. The inclusion criteria were American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification I–II, Child–Pugh class A or B, age between 18 and 65 years, and a single tumor of size ≤5 cm or not more than three tumor nodules ≤3 cm. The exclusion criteria were: prior treatment for liver cancer (such as transarterial chemoembolization and liver resection); recent α2 agonist use; being allergic to any of the drugs used in this study; operation time <30 min or >3 h; history of serious impairment in respiratory, cardiovascular (heart block, myocardial ischemia, or uncontrolled high blood pressure), renal, or central nervous functions; long-term use of psychiatric or neurological drugs; and severe hearing disability. The patients were allowed to quit the study at any time.

After obtaining informed consent from all participants, trained staff used a computer-generated randomization code to randomize the patients into a remifentanil group (REMI group) or a dexmedetomidine group (DEX group) in a 1:1 ratio. For ethical reasons, patient safety, and drug dosing, the anesthesiologists in charge were not blinded to the study drugs, but group allocation was concealed from the patients and data analysts.

Study design

Patients received no premedication. Heart rate (HR), peripheral arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2), non-invasive blood pressure, and bispectral index were monitored continuously (MP60, Philips, Boeblingen, Germany). In the DEX group, 200 μg dexmedetomidine diluted to a concentration of 4 μg mL− 1 was administered as a 0.4 μg kg− 1 bolus infusion 15 min before the induction of anesthesia and continued at a rate of 0.2 μg kg− 1 h− 1 until 10 min before the end of the surgery. In the REMI group, 1 mg remifentanil diluted to a concentration of 20 μg mL− 1 was administered continuously at a rate of 3 μg kg− 1 h− 1 from 15 min before the induction of anesthesia until the end of the surgery.

General anesthesia was induced with propofol (1.5 mg kg− 1), fentanyl (3.0 μg kg− 1), and cisatracurium (0.2 mg kg− 1). After tracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained at a bispectral index of 45–55 with sevoflurane inhalation. At 5 min before the end of surgery, tropisetron was administered at a dose of 0.1 mg kg− 1 (maximum total dose, 5 mg). Sevoflurane was stopped at the end of the surgery (the end of the last RFA procedure).

On occasion, bolus doses of dopamine (2 mg) were administered to avoid hypotension (defined as a >30% decrease in mean arterial pressure [MAP] from the baseline value [before anesthesia induction]) [24, 25]. Atropine was administered at doses of 0.25 mg to avoid bradycardia (defined as HR < 50 beats per minute). These doses were repeated as necessary. Serious drug-related adverse events should be avoided, such as allergic reactions and refractory hemodynamic events (refractory hypotension and bradycardia were defined as hypotension or bradycardia that persisted for at least 10 min despite administering more than three doses of dopamine or atropine). If these events occurred intraoperatively, the anesthesiologist had immediately to terminate the drug infusion, take the necessary measures, and record the circumstances.

After the surgery, patients were transferred to a post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). Immediately when the patients awoke, they were extubated and questioned about their pain intensity and comfort. Pain intensity was assessed with a visual analog scale (VAS; 0–10 cm, handheld slide-rule type). If the VAS score was 3 or more, a bolus of 2 mg (body weight < 60 kg) or 3 mg (body weight > 60 kg) morphine [26–28] was administered intravenously. VAS scores were obtained every 5 min until pain relief, which was defined as a VAS score of <3. If the respiratory rate was <12 breaths/min, SpO2 was < 95%, or a serious adverse event (such as an allergic reaction, vomiting, or severe pruritus) related to morphine administration occurred, the morphine infusion was stopped. After the patients were transferred back to the ward, appropriate analgesics were administered if the patients complained of serious pain with VAS scores ≥3. Liver function was tested at least three times in the first three days after the surgery.

Outcomes and data collection

The primary outcome (endpoint) was postoperative pain intensity, which was assessed by VAS scores. These scores were assessed every 5 min starting from the time of extubation in the PACU and were assessed daily during the first 3 postoperative days when the patients had returned to the ward. A trained investigator blinded to the group assignment performed the assessments for all patients.

Secondary outcomes (endpoints) included analgesic requirement, liver function, patient comfort, and hemodynamic changes. The intraoperative anesthetic requirement, which was the concentration of inhaled sevoflurane, was monitored every 15 min after the start of surgery, and the total dosage of sevoflurane was recorded. Postoperative analgesic administration, including that in the PACU and the ward, was also recorded. Preoperative liver function and the peak or nadir of liver-function data in the first three postoperative days were recorded, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin (ALB), total bilirubin (TBIL), prothrombin time (PT), and PT activity (PT%). Sedation–agitation scale (SAS) scores (Table 1) [29] were recorded every 5 min in the PACU. We also documented the time to emergence, which was defined as the interval between the end of the surgery and a response to a verbal command to open the eyes, which was assessed every 3 min, as well as the time to extubation. Patients’ general condition and comfort after the surgery were evaluated by assessing the rates of disorientation (patients were asked where they were), sore throats, hoarseness, headache, dizziness, discomfort, cold, nausea, vomiting, and intraoperative awareness. Hemodynamic data (HR and MAP) were monitored continuously and recorded at the following time points: before the administration of remifentanil or dexmedetomidine (baseline); 5, 10, and 15 min after their administration; at the time of intubation; 1, 2, and 5 min after intubation; at the start of the surgery; 15, 30, 45, and 60 min after the start of the surgery; when the patient was transferred to the PACU; 5 min after transfer to the PACU; at the time of extubation; and 1 and 5 min after extubation.

Table 1.

Sedation–agitation scale (SAS)

| Score | Term | Patients’ behavior |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | Dangerous agitation | Pulling at endotracheal tube, trying to remove catheters, climbing over bed rail, striking at staff, thrashing from side to side |

| 6 | Very agitated | Does not calm down despite frequent verbal reminders, requires physical restraints, bites endotracheal tube |

| 5 | Agitated | Anxious or mildly agitated, attempting to sit up, calms down with verbal instructions |

| 4 | Calm and cooperative | Calm, awakens easily, follows commands |

| 3 | Sedated | Difficult to arouse, awakens to verbal stimuli or gentle shaking but drifts off again, follows simple commands |

| 2 | Very sedated | Arouses to physical stimuli but does not communicate or follow commands, may move spontaneously |

| 1 | Unarousable | Minimal or no response to noxious stimuli, does not communicate or follow commands |

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the incidence of pain, defined as a VAS score ≥3. Our pre-experimental data indicated that this incidence would be 10% in the DEX group and 40% in the REMI group. The following formula [30] was used to determine the sample size: n = 15.7 / h2 where h = ∣Φ1 − Φ2∣, where Φ1 is the arcsine transformation for the DEX group and Φ2 is the arcsine transformation for the REMI group, assuming α = 0.05, β = 0.2, and a 20% dropout rate. Therefore, the study required 47 patients in each group.

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median and interquartile range, or proportions, and were analyzed using the SPSS v20.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Parametric data were analyzed using analysis of variance, and nonparametric data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. MAP, HR, and sevoflurane concentration were evaluated using repeated-measures analysis of variance and the t-test. Time to emergence and time to extubation were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze proportions. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

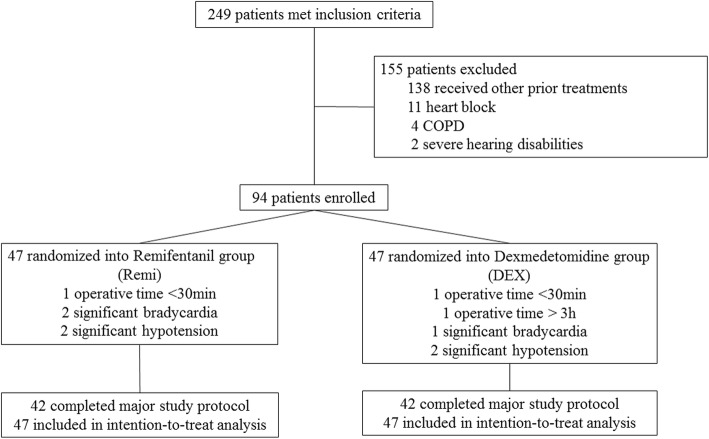

We screened 245 consecutive patients and enrolled 94 patients into this study. Five patients from each group either had an operative time outside our limits or experienced refractory intraoperative bradycardia or hypotension. Thus, finally, 42 patients in each group strictly completed the study protocol and in its entirety, but all 47 patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis (Fig. 1 and Additional file 2). The baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups in terms of demographics and preoperative liver function (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Patient enrollment and randomization. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 2.

Preoperative characteristics of the patients

| Characteristic | Remifentanil | Dexmedetomidine |

|---|---|---|

| n = 47 (50.00%) | n = 47 (50.00%) | |

| Age (years) | 49.57 ± 11.09 | 51.17 ± 10.15 |

| Sex (male/female) | 44/3 | 38/9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.73 ± 3.12 | 21.89 ± 2.65 |

| Baseline AST (U/L) | 37.60 ± 14.77 | 37.36 ± 20.12 |

| Baseline ALT (U/L) | 37.68 ± 22.20 | 35.55 ± 21.91 |

| Baseline ALB (g/L) | 40.20 ± 5.05 | 39.73 ± 4.17 |

| Baseline TBIL (μmol/L) | 20.15 ± 15.55 | 18.29 ± 12.56 |

| Baseline PT (s) | 14.46 ± 1.23 | 14.27 ± 1.59 |

| Baseline PT% activity | 85.34 ± 14.42 | 85.57 ± 14.49 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, or numbers. None of the variables significantly differed between the two groups (P > 0.05)

ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALB albumin, TBIL total bilirubin, PT prothrombin time

Primary outcomes

VAS scores and the incidence of postoperative pain (VAS score ≥ 3) did not significantly differ between the two groups at any time point (P > 0.05; Table 3). The analgesic requirement did not significantly differ between the two groups within the time frame of the focus after the surgery (P > 0.05; Table 3). The incidence of postoperative pain at 48 h after surgery in the REMI group was significantly different from the incidence at the end of surgery (8.51% vs. 27.66%, P = 0.030). There were no significant differences at other time points in the same group (P > 0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence of postoperative pain, defined as a VAS score ≥ 3 and analgesic administration in the study groups

| Parameter | Remifentanil (n = 47) | Dexmedetomidine (n = 47) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS score | |||

| At the end of surgery | 1 (0, 3) | 0 (0, 2) | 0.095 |

| 8 h after surgery | 2 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 3) | 0.637 |

| 24 h after surgery | 1 (0, 3) | 0 (0, 2) | 0.785 |

| 48 h after surgery | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 2) | 0.261 |

| Patients with VAS score ≥ 3 | |||

| At the end of surgery | 13 (27.66) | 7 (14.89) | 0.207 |

| 8 h after surgery | 19 (40.43) | 15 (31.91) | 0.520 |

| 24 h after surgery | 12 (25.53) | 8 (17.02) | 0.450 |

| 48 h after surgery | 4 (8.51)* | 9 (19.15) | 0.231 |

| Patients requiring analgesic administration | |||

| Within 8 h after surgery | 24 (51.06) | 17 (36.17) | 0.212 |

| Within 72 h after surgery | 30 (63.83) | 24 (51.06) | 0.297 |

| Patients who required analgesics or had a VAS score ≥ 3 after transfer out of the PACU | 26 (55.32) | 22 (46.81) | 0.536 |

Values expressed as median (25% percentile, 75% percentile), or number (percentages)

PACU post-anesthesia care unit, VAS visual analog scale

*P < 0.05 vs. patients with VAS score ≥ 3 at the end of surgery

Secondary outcomes

Immediately after extubation, the general condition of the patients, in terms of disorientation, sore throat, hoarseness, headaches, dizziness, discomfort, cold, nausea, vomiting, and intraoperative awareness, was similar in both groups (P > 0.05; Table 4). Liver function was assessed on the first 3 postoperative days. The peak ALT, AST, and TBIL levels were slightly higher in the DEX group, while the nadir ALB and PT% activity and peak PT levels were slightly lower in the REMI group, but the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05; Table 5). All of the liver functions tested were significantly worse postoperatively than preoperatively (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

General condition and comfort of patients after the surgery

| Remifentanil (n = 47) | Dexmedetomidine (n = 47) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disorientation | 5 (10.64) | 5 (10.64) | 1.000 |

| Sore throat | 8 (17.02) | 9 (19.15) | 1.000 |

| Hoarseness | 2 (4.26) | 3 (6.38) | 1.000 |

| Headache | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.13) | 1.000 |

| Dizziness | 3 (6.38) | 4 (8.51) | 1.000 |

| Uncomfortable | 2 (4.26) | 4 (8.51) | 0.677 |

| Cold | 0 (0.00) | 3 (6.38) | 0.242 |

| Nausea | 2 (4.26) | 7 (14.89) | 0.158 |

| Vomiting | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | – |

| Intraoperative awareness | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | – |

Values expressed as number of patients with percentages in parentheses

Table 5.

Postoperative laboratory data during the first 3 postoperative days

| Remifentanil (n = 47) | Dexmedetomidine (n = 47) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak AST (U/L) | 293.15 ± 208.68 | 285.98 ± 131.67 | 0.843 |

| Peak ALT (U/L) | 240.48 ± 196.20 | 265.17 ± 207.06 | 0.557 |

| Nadir ALB (g/L) | 34.62 ± 5.44 | 32.92 ± 6.82 | 0.190 |

| Peak TBIL (μmol/L) | 42.32 ± 30.97 | 49.21 ± 55.05 | 0.468 |

| Peak PT (s) | 17.06 ± 6.26 | 16.23 ± 5.12 | 0.522 |

| Nadir PT% activity | 71.72 ± 12.68 | 73.54 ± 13.29 | 0.540 |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation

ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALB albumin, TBIL total bilirubin, PT prothrombin time

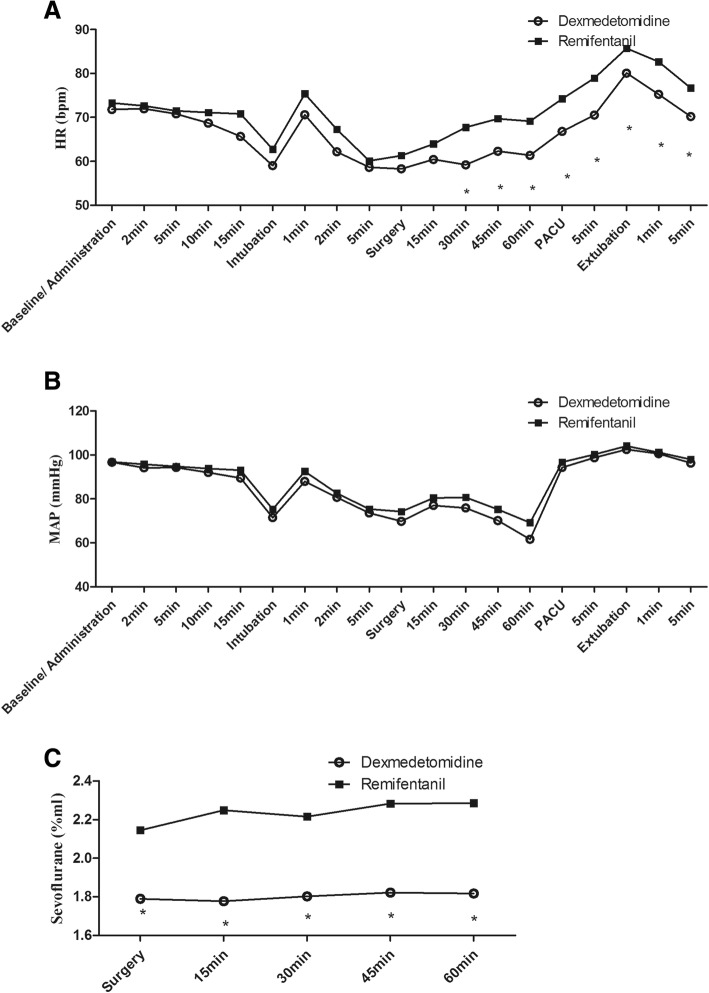

Repeated-measures analysis of variance revealed significant variation in HR and MAP over time within each group (Fig. 2a, b). HR was significantly lower in the DEX group than in the REMI group at 1 min after intubation (70.62 ± 12.93 vs. 75.38 ± 15.46, P = 0.018), 30 min after the start of surgery (59.21 ± 8.26 vs. 67.76 ± 12.90, P < 0.001), and during recovery (P < 0.005; Table 6). Hypotension (34.04% vs. 23.40%, P = 0.362) and bradycardia (34.04% vs. 40.43%, P = 0.670) (requiring treatment with dopamine or atropine) occurred in both groups, but their incidence did not differ between the two groups (Table 7). Refractory hypotension (4.26% vs. 4.26%, P = 1.000) and bradycardia (4.26% vs. 2.13%, P = 1.000) also occurred in both groups, but their incidences were not significantly different (Table 7).

Fig. 2.

Hemodynamic changes during the observation period: a heart rate (HR), b mean arterial pressure (MAP), and c sevoflurane concentration during surgery. HR heart rate, MAP mean arterial pressure, PACU post-anesthesia care unit. *P < 0.05 vs. the REMI group

Table 6.

Intraoperative hemodynamic data

| Mean arterial blood pressure (mm Hg) | Heart rate (beats/min) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remifentanil | Dexmedetomidine | P | Remifentanil | Dexmedetomidine | P | |

| Baseline/ administration | 96.83 ± 10.42 | 96.69 ± 9.70 | 0.943 | 73.28 ± 11.74 | 71.81 ± 13.41 | 0.574 |

| 2 min | 95.74 ± 10.52 | 94.19 ± 10.77 | 0.481 | 72.64 ± 12.37 | 71.98 ± 13.65 | 0.807 |

| 5 min | 94.79 ± 11.14 | 94.32 ± 9.91 | 0.830 | 71.47 ± 10.62 | 70.81 ± 13.44 | 0.792 |

| 10 min | 93.81 ± 10.82 | 92.04 ± 10.45 | 0.423 | 71.11 ± 11.02 | 68.70 ± 13.89 | 0.355 |

| 15 min | 93.04 ± 11.29 | 89.49 ± 11.53 | 0.135 | 70.83 ± 12.58 | 65.68 ± 12.75 | 0.052 |

| Intubation | 75.28 ± 11.00 | 71.53 ± 12.30 | 0.123 | 62.77 ± 9.54 | 59.06 ± 11.71 | 0.096 |

| 1 min | 92.47 ± 15.35 | 87.94 ± 15.49 | 0.158 | 75.38 ± 15.46 | 70.62 ± 12.93 | 0.018 |

| 2 min | 82.60 ± 11.31 | 80.70 ± 12.27 | 0.439 | 67.30 ± 13.06 | 62.36 ± 11.56 | 0.055 |

| 5 min | 75.38 ± 10.10 | 73.66 ± 9.67 | 0.400 | 60.13 ± 10.84 | 58.64 ± 10.33 | 0.497 |

| Surgery | 74.21 ± 10.83 | 69.85 ± 11.20 | 0.058 | 61.32 ± 9.00 | 58.33 ± 9.50 | 0.122 |

| 15 min | 80.43 ± 10.84 | 77.00 ± 16.01 | 0.299 | 63.98 ± 8.55 | 60.45 ± 9.73 | 0.071 |

| 30 min | 80.68 ± 16.89 | 75.91 ± 17.40 | 0.183 | 67.76 ± 12.90 | 59.21 ± 8.26 | < 0.001 |

| 45 min | 75.26 ± 21.10 | 70.18 ± 25.82 | 0.306 | 69.71 ± 11.18 | 62.32 ± 8.44 | 0.002 |

| 60 min | 69.22 ± 22.83 | 61.62 ± 24.67 | 0.139 | 69.15 ± 8.45 | 61.37 ± 9.61 | 0.001 |

| PACU | 96.72 ± 11.62 | 94.30 ± 11.98 | 0.322 | 74.24 ± 11.64 | 66.82 ± 13.01 | 0.005 |

| 5 min | 100.26 ± 12.24 | 98.77 ± 12.24 | 0.577 | 78.93 ± 13.73 | 70.56 ± 14.42 | 0.006 |

| Extubation | 104.13 ± 13.85 | 102.47 ± 10.22 | 0.510 | 85.70 ± 14.11 | 80.09 ± 12.66 | 0.045 |

| 1 min | 101.17 ± 12.63 | 100.57 ± 8.75 | 0.791 | 82.66 ± 13.08 | 75.23 ± 12.39 | 0.006 |

| 5 min | 97.96 ± 9.41 | 96.30 ± 9.45 | 0.396 | 76.68 ± 12.07 | 70.21 ± 10.52 | 0.007 |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation

PACU post-anesthesia care unit

Table 7.

Number of patients with hypotension or bradycardia

| Remifentanil (n = 47) | Dexmedetomidine (n = 47) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotension | 11 (23.40) | 16 (34.04) | 0.362 |

| Bradycardia | 19 (40.43) | 16 (34.04) | 0.670 |

| Refractory hypotension | 2 (4.26) | 2 (4.26) | 1.000 |

| Refractory bradycardia | 1 (2.13) | 2 (4.26) | 1.000 |

Values expressed as numbers and percentages

At each measured time point during the surgery, the concentration of inhaled sevoflurane was significantly lower in the DEX group than in the REMI group (Fig. 2c). Anesthesia time did not significantly differ between the two groups, but there were significant differences in the total dosage of sevoflurane (22.77 ± 11.18 vs. 17.58 ± 11.22 mL, P = 0.017) and the sevoflurane dosage related to anesthesia time (16.41 ± 5.74 vs. 11.56 ± 5.20 mL h− 1, P < 0.001; Table 8). Delayed emergence was defined as a time to emergence of over 30 min. Although there were more patients with delayed emergence in the DEX group (12.77% vs. 4.26%), the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.267; Table 9). Time to emergence, time to extubation, and the number of patients with a postoperative SAS score of ≥5 did not significantly differ between the two groups (Table 9).

Table 8.

Dosage of sevoflurane

| Remifentanil (n = 47) | Dexmedetomidine (n = 47) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia time (h) | 1.37 ± 0.52 | 1.14 ± 0.64 | 0.767 |

| Total dosage of sevoflurane (mL) | 22.77 ± 11.18 | 17.58 ± 11.22 | 0.017 |

| Sevoflurane related to anesthesia time (mL h−1) | 16.41 ± 5.74 | 11.56 ± 5.20 | < 0.001 |

Table 9.

Emergence from anesthesia

| Remifentanil (n = 47) | Dexmedetomidine (n = 47) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with delayed emergence | 2 (4.26) | 6 (12.77) | 0.267 |

| Time to emergence (min)* | 14 (11, 18) | 15 (10, 24) | 0.066 |

| Time to extubation (min)* | 19 (15, 25) | 19 (15, 29) | 0.051 |

| Patients with SAS ≥ 5 at extubation | 2 (4.26) | 6 (12.77) | 0.267 |

| Patients with SAS ≥ 5 at 1 min after extubation | 0 (0.00) | 2 (4.26) | 0.495 |

| Patients with SAS ≥ 5 at 5 min after extubation | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.13) | 1.000 |

Values expressed as numbers and percentages, or medians and interquartile ranges (25th percentile, 75th percentile)

SAS Sedation-Agitation scale

*Mann–Whitney U-test

Discussion

Unlike other studies or our pre-experiment, this study showed that compared with remifentanil, dexmedetomidine did not significantly reduce postoperative pain or analgesic consumption in patients undergoing RFA for small HCCs. However, dexmedetomidine significantly reduced the demand for inhaled anesthetics and inhibited an increase in HR during extubation. It did not influence immediate postoperative patient comfort, exacerbate liver-function impairment during the first 3 postoperative days, or delay recovery from anesthesia.

Dexmedetomidine is a selective α2-adrenoreceptor agonist, with superior sedative, anxiolytic, and analgesic properties. Several studies have shown that dexmedetomidine decreases VAS scores, analgesic requirement, and opioid-related adverse events [31–33]. Dexmedetomidine exhibits a synergistic effect with the opioid system and might potentiate the analgesic effect of other analgesic drugs [34, 35]. In some reports, dexmedetomidine has exhibited superior efficacy in pain management compared to remifentanil during a PACU stay after general anesthesia [36, 37]. Dexmedetomidine also has opioid-sparing properties [38, 39]. This might partially explain why fewer patients in the DEX group had VAS scores of ≥3 in the present study. However, the difference was not statistically significant, and dexmedetomidine did not show any advantages over remifentanil in terms of VAS scores or analgesic consumption. The discrepancy between the above findings and those of our study might be attributable to the effect of local hyperthermia on the liver capsule, and peripheral nerves and vessels, and inadequate analgesia provided by the two study drugs. The analgesic effects of the drugs were dose dependent. In our study, dexmedetomidine and remifentanil were administered intraoperatively, and other preventive analgesic drugs were not used. Furthermore, although RFA is more rapid and less invasive than liver resection, unfortunately, 14.89–40.43% of patients complained of pain after RFA in this study.

Remifentanil can provide rapid recovery from anesthesia, but occasionally opioid-induced hyperalgesia can emerge after long-term infusion [40], though the evidence is conflicting [41]. The analgesic effect of remifentanil fades within 3–10 min. Immediately after extubation, 13 patients (27.66%) in the REMI group, who could be considered to be without any analgesia, experienced significant pain. At 48 h later, the pain caused by surgery was significantly reduced, and the proportion of patients complaining of pain decreased significantly (P = 0.030). The above difference might be due to the higher proportion at the end of surgery, and the rapid decline 48 h later.

Further analysis showed that the number of patients with pain peaked at 8 h after the surgery (40.43% and 31.91% in the REMI and DEX groups, respectively), and approximately half the patients in each group required analgesics or had a VAS score of ≥3 even after transferring out of the PACU. This suggests that in addition to the administration of analgesics at the end of the surgery, prophylactic analgesia may be required until the patient is transferred to the ward, especially in the first 8 h following surgery.

RFA is a safe treatment for HCC associated with mild liver dysfunction but has the potential to aggravate preexisting hepatic dysfunction [42]. Transient liver dysfunction after RFA is common. AST, ALT, and TBIL levels peak at 12–24 h after RFA [43]. Remifentanil is metabolized by nonspecific esterases present mainly in the blood and is considered to have no effect on liver function. In contrast, dexmedetomidine is metabolized by the liver, and one study has reported that high doses could induce oxidative stress in liver tissue [44]. However, several studies [22, 23, 45] have shown that dexmedetomidine has a protective effect against liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. In the present study, postoperative liver function was not significantly different between the two groups and the protective effect of dexmedetomidine was not observed. Possible reasons for this finding might be that the liver dysfunction caused by RFA was minimal and differed from ischemia-reperfusion injury. However, the precise reasons require further investigation.

Remifentanil provides hemodynamic stability and attenuates the stress response but is commonly associated with side effects, such as bradycardia (2–12%) and hypotension (6–30%), which are strongly dose dependent [46, 47]. Drops in HR, such as those observed in our study, are mainly caused by centrally mediated sympatholytic and/or vagotonic actions, whereas drops in blood pressure are mainly the result of direct vasodilation [48, 49]. Dexmedetomidine reduces catecholamine secretion, soothes the stress response to endotracheal intubation or extubation, and maintains hemodynamic stability during the intraoperative period, all of which are outstanding advantages [50, 51]. The cardiovascular effects of dexmedetomidine mainly result from peripheral and central α2-adrenoreceptor activation [52]. The reduction of stress and analgesic effects might play a key role. The causes of bradycardia might be central sympatholytic action, activation of the baroreceptor reflex, and enhanced vagal activity. This effect is expected to blunt changes in HR. Some researchers believe that significant hypotension caused by dexmedetomidine is usually observed only in patients with preexisting vasoconstriction or hypovolemia [53]. In one study, the incidence of hypotension requiring intervention was slightly higher in patients receiving high-dose dexmedetomidine than in those receiving lower doses [54]. In the present study, as all patients had some hepatic dysfunction, we selected low drug doses (0.4 μg kg− 1 bolus and maintenance with 0.2 μg kg− 1 h− 1), which we believed would have a lesser impact on hemodynamics, including hypotension and bradycardia [55–57]. Although hypotension and bradycardia still occurred in our study, HRs were stable during postoperative recovery in the DEX group.

Another important observation of our study was that dexmedetomidine, as previously reported [58], significantly reduced the demand for inhalational anesthetics, without affecting the time to emergence or extubation. Although one study [59] found that dexmedetomidine is associated with delayed recovery, several others [60–62] have reported that as an adjuvant to general anesthesia, dexmedetomidine results in more stable hemodynamics, better recovery, and easy extubation, without affecting recovery time. One possible reason for this difference is that inhaled anesthetics are rapidly discharged due to lower intraoperative demand, and the time to emergence and extubation might be influenced more by the anesthetic dose than by the administration of analgesics.

Our study has certain limitations. First, the specifics of the RFA procedures, including power output, time, and location, were not the same for each patient owing to differences in patient conditions and ethical requirements. A multicenter large-scale trial could resolve this problem. Second, for patient safety, the anesthesiologists in charge were not blinded to the drugs used in the surgeries, and this could lead to bias. Third, only 3 days of follow-up were performed, which might be inadequate to assess prognosis. Longer observation is necessary to obtain more complete and meaningful comparisons.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the perioperative administration of low-dose dexmedetomidine to patients undergoing RFA reduced their HRs and the requirement for inhalational anesthetics, and did not exacerbate postoperative discomfort or liver dysfunction. Although dexmedetomidine did not reduce postoperative pain scores or exhibit an analgesic-sparing effect compared with remifentanil, it appeared to be a safe optional adjunct and it appeared that postoperative pain was strictly controlled in all RFA patients.

Additional files

CONSORT-Equity checklist. (DOCX 18 kb)

CONSORT-Equity flow diagram. Intervention A denotes remifentanil and intervention B denotes dexmedetomidine. (DOC 70 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Authors’ contributions

JP and XL contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. YH, CJ, and HC contributed to the acquisition of the data. ZH and SZ contributed to study concept and design, and study supervision.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was provided by the ethics committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat Sen University, Guangzhou, China on 5 May 2015.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jingru Pan, Email: panjingruph@163.com.

Xianlong Li, Email: 286510848@qq.com.

Ye He, Email: shuigua0213@163.com.

Chaojun Jian, Email: 506496053@qq.com.

Hui-xin Chen, Email: chenhuixinsysu@163.com.

Ziqing Hei, Phone: 86-20-85252297, Email: heiziqing@sina.com.

Shaoli Zhou, Phone: 86-20-85252297, Email: shaolizhou@139.com.

References

- 1.Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, Lin XJ, Lau WY. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;243(3):321–328. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lahat E, Eshkenazy R, Zendel A, Zakai BB, Maor M, Dreznik Y, Ariche A. Complications after percutaneous ablation of liver tumors: a systematic review. Hepatob Surg Nutr. 2014;3(5):317–323. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2014.09.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lencioni R, Cioni D, Crocetti L, Franchini C, Pina CD, Lera J, Bartolozzi C. Early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: long-term results of percutaneous image-guided radiofrequency ablation. Radiology. 2005;234(3):961–967. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343040350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tateishi R, Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Koike Y, Fujishima T, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Omata M. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1201–1209. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang W, Yan K, Goldberg SN, Ahmed M, Lee JC, Wu W, Zhang ZY, Wang S, Chen MH. Ten-year survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation as a first-line treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(10):2993–3005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i10.2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.N'Kontchou G, Mahamoudi A, Aout M, Ganne-Carrie N, Grando V, Coderc E, Vicaut E, Trinchet JC, Sellier N, Beaugrand M, Seror O. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term results and prognostic factors in 235 Western patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50(5):1475–1483. doi: 10.1002/hep.23181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livraghi T, Meloni F, Di Stasi M, Rolle E, Solbiati L, Tinelli C, Rossi S. Sustained complete response and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology 2008;47(1):82–89. Epub 2007/11/17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Takasaki J, Arai K, Ando M, Nagahama T, Fukuda A, Ami K, Kurokawa T, Ganno H, Amagasa H, Watayou Y, Fujiya K, Nakamura M, Katagiri S, Yoneda G, Yamamoto M, Saito A. Examination of the effect of anesthesia on radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma-a patient survey on anesthesia for radiofrequency ablation. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho Cancer Chemother. 2012;39(12):1843–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai R, Peng Z, Chen D, Wang X, Xing W, Zeng W, Chen M. The effects of anesthetic technique on cancer recurrence in percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(2):290–296. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318239c2e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang LL, Ji JS, Wu W, Lei LP, Zhao ZW, Shao GL, Zheng JP. Clinical observation of remifentanyl and propofol injection in total intravenous anesthesia for percutaneous radiofrequency ablation. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;93(45):3623–3625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Huang W, Long YH, Li W, Wang J, Chen MS, Xu MX. Application of total intravenous anesthesia with remifentanyl and propofol to radiofrequency ablation. Ai Zheng. 2007;26(3):322–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeSouza G, Lewis MC, TerRiet MF. Severe bradycardia after remifentanil. Anesthesiology. 1997;87(4):1019–1020. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhana N, Goa KL, McClellan KJ. Dexmedetomidine. Drugs. 2000;59(2):263–268. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauber JA, Davis PJ, Bendel LP, Martyn SV, McCarthy DL, Evans MC, Cladis FP, Cunningham S, Lang RS, Campbell NF, Tuchman JB, Young MC. Dexmedetomidine as a Rapid Bolus for Treatment and Prophylactic Prevention of Emergence Agitation in Anesthetized Children. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(5):1308–1315. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Han R, Zuo Z. Dexmedetomidine post-treatment induces neuroprotection via activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in rats with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116(3):384–392. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Wang Y, Ning Q, Zhang Y, Gong C, Zhao W, Jing G, Wang Q. Dexmedetomidine attenuates inflammatory reaction in the lung tissues of septic mice by activating cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;35:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu L, Hu Z, Shen J, McQuillan PM. Does dexmedetomidine have a cardiac protective effect during non-cardiac surgery? A randomised controlled trial. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41(11):879–883. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng X, Wang H, Xing X, Wang Q, Li W. Dexmedetomidine Protects against Transient Global Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Diabetic Rats. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang L, Li L, Shen J, Qi Z, Guo L. Effect of dexmedetomidine on lung ischemiareperfusion injury. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9(2):419–426. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu YE, Tong CC, Zhang YB, Jin HX, Gao Y, Hou MX. Effect of dexmedetomidine on rats with renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and the expression of tight junction protein in kidney. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(10):18751–18757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahin T, Begec Z, Toprak HI, Polat A, Vardi N, Yucel A, Durmus M, Ersoy MO. The effects of dexmedetomidine on liver ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JH, Yu GF, Jin SY, Zhang WH, Lei DX, Zhou SL, Song XR. Activation of alpha2 adrenoceptor attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatic injury. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(9):10752–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klimscha W, Weinstabl C, Ilias W, Mayer N, Kashanipour A, Schneider B, Hammerle A. Continuous spinal anesthesia with a microcatheter and low-dose bupivacaine decreases the hemodynamic effects of centroneuraxis blocks in elderly patients. Anesth Analg. 1993;77(2):275–280. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199377020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biboulet P, Jourdan A, Van Haevre V, Morau D, Bernard N, Bringuier S, Capdevila X. Hemodynamic profile of target-controlled spinal anesthesia compared with 2 target-controlled general anesthesia techniques in elderly patients with cardiac comorbidities. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012;37(4):433–440. Epub 2012/05/23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Saumier N, Gentili M, Dupont H, Aubrun F. Postoperative intravenous morphine titration in PACU after bariatric laparoscopic surgery. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2013;32(12):850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abou Hammoud H, Simon N, Urien S, Riou B, Lechat P, Aubrun F. Intravenous morphine titration in immediate postoperative pain management: population kinetic-pharmacodynamic and logistic regression analysis. Pain. 2009;144(1–2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aubrun F, Monsel S, Langeron O, Coriat P, Riou B. Postoperative titration of intravenous morphine. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2001;18(3):159–165. doi: 10.1097/00003643-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riker RR, Picard JT, Fraser GL. Prospective evaluation of the Sedation-Agitation Scale for adult critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(7):1325–1329. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lerman J. Study design in clinical research: sample size estimation and power analysis. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43(2):184–191. doi: 10.1007/BF03011261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan AK, Cheung CW, Chong YK. Alpha-2 agonists in acute pain management. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(17):2849–2868. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2010.511613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurbet A, Basagan-Mogol E, Turker G, Ugun F, Kaya FN, Ozcan B. Intraoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine reduces perioperative analgesic requirements. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(7):646–652. doi: 10.1007/BF03021622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnabel A, Meyer-Friessem CH, Reichl SU, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Is intraoperative dexmedetomidine a new option for postoperative pain treatment? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain. 2013;154(7):1140–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ulger F, Bozkurt A, Bilge SS, Ilkaya F, Dilek A, Bostanci MO, Ciftcioglu E, Guldogus F. The antinociceptive effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine in colorectal distension-induced visceral pain in rats: the role of opioid receptors. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(2):616–622. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a9fae2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudo RT, Calasans-Maia JA, Galdino SL, Lima MC, Zapata-Sudo G, Hernandes MZ, Pitta IR. Interaction of morphine with a new alpha2-adrenoceptor agonist in mice. J Pain. 2010;11(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turgut N, Turkmen A, Ali A, Altan A. Remifentanil-propofol vs dexmedetomidine-propofol--anesthesia for supratentorial craniotomy. Mid East J Anaesth. 2009;20(1):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang W, Lee J, Park J, Joo J. Dexmedetomidine versus remifentanil in postoperative pain control after spinal surgery: a randomized controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:21. doi: 10.1186/s12871-015-0004-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haselman MA. Dexmedetomidine: a useful adjunct to consider in some high-risk situations. AANA J. 2008;76(5):335–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arain SR, Ruehlow RM, Uhrich TD, Ebert TJ. The efficacy of dexmedetomidine versus morphine for postoperative analgesia after major inpatient surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(1):153–158. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000093225.39866.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Celerier E, Gonzalez JR, Maldonado R, Cabanero D, Puig MM. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in a murine model of postoperative pain: role of nitric oxide generated from the inducible nitric oxide synthase. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(3):546–555. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivosecchi RM, Rice MJ, Smithburger PL, Buckley MS, Coons JC, Kane-Gill SL. An evidence based systematic review of remifentanil associated opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(5):587–603. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.902931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim YK, Kim CS, Chung GH, Han YM, Lee SY, Jin GY, Lee JM. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: evaluation of therapeutic efficacy and safety. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(5 Suppl):S261–S268. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cizginer S, Tatli S, Hurwitz S, Tuncali K. vanSonnenberg E, Silverman SG. Biochemical and hematologic changes after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors: experience in 83 procedures. J Vasc Interven Radiol. 2011;22(4):471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kucuk A, Yaylak F, Cavunt-Bayraktar A, Tosun M, Arslan M, Comu FM, Kavutcu M. The protective effects of dexmedetomidine on hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury. Bratislavske Lekarske Listy. 2014;115(11):680–684. doi: 10.4149/bll_2014_132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang ZX, Huang CY, Hua YP, Huang WQ, Deng LH, Liu KX. Dexmedetomidine reduces intestinal and hepatic injury after hepatectomy with inflow occlusion under general anaesthesia: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112(6):1055–1064. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdel Hamid AM, Abo Shady AF, Abdel Azeem ES. Remifentanil infusion as a modality for opioid-based anaesthesia in paediatric practice. Ind J Anaesth. 2010;54(4):318–323. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.68375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scott LJ, Perry CM. Remifentanil: a review of its use during the induction and maintenance of general anaesthesia. Drugs. 2005;65(13):1793–1823. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565130-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maruyama K, Nishikawa Y, Nakagawa H, Ariyama J, Kitamura A, Hayashida M. Can intravenous atropine prevent bradycardia and hypotension during induction of total intravenous anesthesia with propofol and remifentanil? J Anesth. 2010;24(2):293–296. doi: 10.1007/s00540-009-0860-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ciftci T, Erbatur S, Ak M. Comparison of the effects of dexmedetomidine and remifentanil on potential extreme haemodynamic and respiratory response following mask ventilation and laryngoscopy in patients with mandibular fractures. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(22):4427–4433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee YY, Wong SM, Hung CT. Dexmedetomidine infusion as a supplement to isoflurane anaesthesia for vitreoretinal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98(4):477–483. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menda F, Koner O, Sayin M, Ture H, Imer P, Aykac B. Dexmedetomidine as an adjunct to anesthetic induction to attenuate hemodynamic response to endotracheal intubation in patients undergoing fast-track CABG. Ann Card Anaesth. 2010;13(1):16–21. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.58829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bloor BC, Ward DS, Belleville JP, Maze M. Effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine in humans. II. Hemodynamic changes. Anesthesiology. 1992;77(6):1134–1142. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arcangeli A, D'Alo C, Gaspari R. Dexmedetomidine use in general anaesthesia. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10(8):687–695. doi: 10.2174/138945009788982423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jessen Lundorf L, Korvenius Nedergaard H, Moller AM. Perioperative dexmedetomidine for acute pain after abdominal surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD010358. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010358.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Basar H, Akpinar S, Doganci N, Buyukkocak U, Kaymak C, Sert O, Apan A. The effects of preanesthetic, single-dose dexmedetomidine on induction, hemodynamic, and cardiovascular parameters. J Clin Anesth. 2008;20(6):431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aho M, Lehtinen AM, Erkola O, Kallio A, Korttila K. The effect of intravenously administered dexmedetomidine on perioperative hemodynamics and isoflurane requirements in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Anesthesiology. 1991;74(6):997–1002. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keniya VM, Ladi S, Naphade R. Dexmedetomidine attenuates sympathoadrenal response to tracheal intubation and reduces perioperative anaesthetic requirement. Ind J Anaesth. 2011;55(4):352–357. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.84846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harsoor SS, Rani DD, Lathashree S, Nethra SS, Sudheesh K. Effect of intraoperative Dexmedetomidine infusion on Sevoflurane requirement and blood glucose levels during entropy-guided general anesthesia. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30(1):25–30. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.125693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anjum N, Tabish H, Debdas S, Bani HP, Rajat C, Anjana Basu GD. Effects of dexmedetomidine and clonidine as propofol adjuvants on intra-operative hemodynamics and recovery profiles in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective randomized comparative study. Avicenna J Med. 2015;5(3):67–73. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.160231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patel CR, Engineer SR, Shah BJ, Madhu S. Effect of intravenous infusion of dexmedetomidine on perioperative haemodynamic changes and postoperative recovery: A study with entropy analysis. Ind J Anaesth. 2012;56(6):542–546. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.104571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turan G, Ozgultekin A, Turan C, Dincer E, Yuksel G. Advantageous effects of dexmedetomidine on haemodynamic and recovery responses during extubation for intracranial surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25(10):816–820. doi: 10.1017/S0265021508004201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aksu R, Akin A, Bicer C, Esmaoglu A, Tosun Z, Boyaci A. Comparison of the effects of dexmedetomidine versus fentanyl on airway reflexes and hemodynamic responses to tracheal extubation during rhinoplasty: A double-blind, randomized, controlled study. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2009;70(3):209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CONSORT-Equity checklist. (DOCX 18 kb)

CONSORT-Equity flow diagram. Intervention A denotes remifentanil and intervention B denotes dexmedetomidine. (DOC 70 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).