Summary

Seeding of amyloid fibrils into fresh solutions of the same peptide or protein in disaggregated form leads to the formation of replicate fibrils (1), with close structural similarity or identity to the original fibrillar seeds. Here we describe procedures for isolating fibrils composed mainly of β-amyloid (Aβ) from human brain and from leptomeninges, a source of cerebral blood vessels, for investigating Alzheimer’s Disease and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. We also describe methods for seeding isotopically labeled, disaggregated Aβ peptide solutions for study using solid-state NMR and other techniques. These methods should be applicable to other types of amyloid fibrils, to Aβ fibrils from mice or other species, tissues other than brain, and to some non-fibrillar aggregates. These procedures allow for the examination of authentic amyloid fibrils and other proteins aggregates from biological tissues without the need for labeling of the tissue.

Keywords: β-amyloid, Alzheimer’s Disease, solid-state NMR, fibril structure, fibril polymorphism, protein aggregation, protein aggregation diseases, neuritic plaques, Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy

1. Introduction

Amyloid fibrils and pre-amyloid protein and peptide aggregates are believed to be pathogenic in Alzheimer’s Disease, and many other diseases within and outside of the central nervous system. The study of the structure of such aggregates remains an important objective both in understanding the disease processes, and in designing diagnostic and therapeutic agents.

A major advance in our understanding of the structure of these protein aggregates has come from the use of solid-state NMR spectroscopy, which allows the interrogation of solid but non-crystalline materials. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy has shown that most amyloid fibrils contain a core of parallel, in-register β-sheets (2–4). More recent studies have elucidated additional structural details, including the supramolecular organization of peptides within the fibril.

The formation of amyloid fibrils and pre-amyloid protein/peptide aggregates represents a failure of protein folding. Aβ, for example, is unstructured in solution, and never adopts a unique three-dimensional fold. In 2005, Petkova et al. found documented polymorphism in Aβ amyloid fibrils (1), based on differences in fibrillization conditions, i.e., whether otherwise identical solutions of Aβ peptide were allowed to form fibrils under “quiescent” or “agitated” conditions (gentle swirling). These results clearly demonstrated that for Aβ amyloid fibrils, structure was not uniquely determined by amino acid sequence. In addition to structural differences, observed at the level of electron microscopy and solid-state NMR spectroscopy, these authors observed differences in cytotoxicity of these two fibrils types in vitro. Subsequent studies elucidated detailed structural models for these two types of Aβ fibrils (5–7). Similar types of polymorphism have been observed with other fibrils of other proteins or peptides (e.g., β2-microglobulin (8) among others). Polymorphism is now believed to be a general property of amyloid fibrils. The variation in fibril structure is also highly reminiscent of the strain phenomenon found in yeast and mammalian prions (9–11).

One of the critical findings from the above studies is that differences in fibril structure can be propagated to “progeny” fibrils through seeding (1). Thus, Aβ fibrils formed under “agitated” conditions can be used as seeds to form fibrils from fresh, disaggregated Aβ solutions, and these will have strong resemblance to the “parent” fibrils structurally – and these structural properties will be relatively independent of fibrillization conditions. The seeds, in other words, “trump” the fibrillization conditions, presumably because most or all of the fibril polymorphism arises at the level of nucleation.

These findings present an excellent opportunity for examining the structures of fibrils from biological material, especially where the usual labeling procedures used in NMR spectroscopy cannot be readily applied. In particular, although the above-cited studies documented polymorphism of Aβ fibrils, it was not known which of these structures – or both or neither – would be found in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease and the related condition of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Reasoning that one can make isotopically labeled Aβ fibrils that were replicates of authentic brain Aβ fibrils from patients dying with Alzheimer’s Disease, we used such material to isolate amyloid fibrils. We then used these fibrils as seeds for generating isotopically labeled replicate Aβ fibrils for study by solid-state NMR. We have shown that amyloid fibrils can be retrieved from brains at autopsy, and then used to generate fibrils from fresh solutions of synthetic Aβ peptides. The synthetic peptides can be labeled by standard procedures. The brain amyloid seeds fibril formation in solutions of synthetic, disaggregated Aβ peptides, and these have been studied by solid-state NMR, electron microscopy, x-ray diffraction, and other biophysical techniques. Using these procedures, we have interrogated the structure of amyloid fibrils occurring in the brains of patients dying with or of Alzheimer’s Disease and its variants (12, 13). NMR spectra of the replicate fibrils show surprisingly sharp peaks, and in general, one or two structural populations in each brain. We have also shown that sampling from multiple regions with a single brain yields replicate fibrils of identical structure, i.e., without variation depending on anatomic location within a single brain. Importantly, we have also observed differences among patients in the structures of their brain-derived amyloid fibrils.

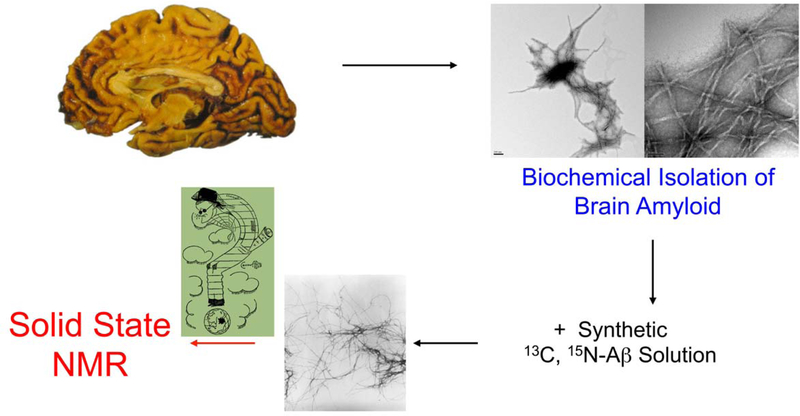

Here, we present procedures for isolating Aβ fibrils from human brains obtained at autopsy from patients dying with or of Alzheimer’s Disease. The procedure is depicted schematically in Fig. 1. We have recently also isolated Aβ fibrils from leptomeninges, as a source of cerebrovascular amyloid, and present these procedures below. We will also describe procedures for using such biochemically isolated amyloid as a seed, to generate replicate progeny fibrils.

1.

Schematic of procedure for forming amyloid fibrils seeded from material obtained from brain or leptomeninges. Amyloid fibrils are isolated by biochemical procedures, and are then added to synthetic (or expressed), isotopically labeled Aβ40 or Aβ42. The resulting replicate fibrils can then be interrogated using solid-state NMR spectroscopy.

We will focus on Aβ fibrils. These procedures, however, should be applicable to diverse types of samples, in particular: 1) fibrils composed of other peptides and proteins; 2) Aβ and other fibrils from non-human species; 3) tissues other than brain; and 4) some non- fibrillar aggregates of Aβ, including soluble oligomeric species.

The following are the main issues and questions about procedures for isolating amyloid fibrils from human brain or other tissues.

How harshly to treat the tissues, i.e., how rigorously to purify the amyloid. Early procedures for isolating amyloid fibrils from brain took advantage of the fact that fibrils are resistant to denaturants, including SDS and acidic conditions, and are protease resistant (14, 15). Prolonged treatment of amyloid fibrils under “harsh” conditions will eventually lead to some loss and degradation of amyloid fibrils, however. Amyloid fibrils constitute a minute fraction of the brain even in patients with advanced Alzheimer’s Disease; thus it is necessary to eliminate most of the material in brains in order to obtain amyloid fibrils that can effectively seed Aβ solutions. Isolation procedures inevitably involve the use of organic solvents, denaturants and proteases. Here we describe procedures to “navigate” the trade-off between obtaining greater purity in the isolated brain amyloid, versus loss of seeding material and potential alteration of the material from harsh isolation procedures.

Which fractions to retain from brain parenchyma or meninges. As discussed below, there are slight differences (e.g., fractions from ultracentrifigation steps) between procedures for isolating amyloid from brain parenchyma or leptomeninges. These differences were based solely on the empirical assessment of the ability of various fractions to seed amyloid formation in solutions of Aβ40. Amyloid represents a fairly small fraction of the total mass of these tissues, and differences presumably reflect difference in the overall composition of the tissues.

Conditions for seeding, particular with respect to the number of “generations” of progeny fibrils. This issue follows directly from the previous one. In earlier studies, more rigorous purification of brain amyloid reduced the overall yield of fibrils. This, in turn, necessitated re-seeding procedures, i.e., the use of first- generation brain-seeded fibrils to form sufficient quantities of second- and third- generation fibrils for solid-state NMR spectroscopy. The procedures presented below allow for the generation of sufficient quantities of labeled fibrils for solid- state NMR from as little as one gram of starting human brain material.

2. Materials

Brains: Brain tissue is obtained at the time of autopsy and is either used immediately or frozen at –80°C (see Note 1).

Homogenization Buffer: 10 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 0.25 M sucrose, 50 μg/mL gentamicin sulfate, 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B, and protease inhibitor (one Roche complete protease inhibitor tablet is added to ~100 mL of Homogenization Buffer before use).

First Ultracentrifugation Buffer: identical to Homogenization Buffer, except that solid sucrose is added to a final concentration of 1.9 M.

Wash Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.00

Digestion Buffer: 50 mM Tris pH 8.00, 2 mM CaCl, 0.2 mg/mL collagenase CLS3 (Worthington), and 0.01 mg/mL DNase I. Between 1 and 10 mL collagenase solution were used, based on the size of the sample.

SDS-Second Ultracentrifugation Buffer: 50 mM Tris pH 8.00, also containing 1.3 M sucrose and 1% (w/v) SDS.

Seeding buffer: 10mM sodium phosphate pH 7.40, also containing 0.01% (w/v) NaN3.

Phosphate buffer (PB): 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.40, also containing 0.01% (w/v) NaN3.

Sonifier: We have used two particular sonifiers: Branson S-250A Sonifier with a tapered 1/8’ inch micro-tip horn, and Branson 450 Sonifier with a equipped with a 1/8th inch micro-tip.

CNBr: Crystalline CNBr should be stored at –20 °C, with the bottle inverted so that the CNBr is continuously re-sublimed. The last quarter or third of the bottle should be discarded.

88% Formic Acid: This is concentrated formic acid as available from vendors. The actual formic acid varies slightly by lot.

3. Methods

3.1. Amyloid Extraction

Brain or leptomeningeal is obtained at autopsy and is placed into a disposable plastic container without fixative.

The tissue is grossly dissected to separate meninges and visible blood vessels.

In brain samples, gray and white matter are separated from one another with a scalpel or razor blade.

At this point, it can be used immediately, or stored frozen (–20 °C).

The tissue was then homogenized in 20 volumes of ice-cold Homogenization Buffer in a Tenbroek homogenizer. The slurry is then stirred overnight at 4°C.

Solid sucrose is then added to the sample to 1.20 M. The sample is centrifuged for 45 minutes at 25,000 × g at 4 °C (see Note 3). The supernatant and upper layer are discarded and the pellet is retained.

The pellet is resuspended in First Ultracentrifugation Buffer, i.e., containing 1.90 M sucrose. It is ultracentrifuged for 30 min at 125,000 × g at 15 °C (see Note 4). For brain parenchymal samples, the upper layer is reserved; for meningeal samples, the pellet is reserved.

The reserved portion is washed twice in Wash Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.00). Approximately 10 volumes of Wash Buffer is added to the reserved portion, which is then centrifuged for five minutes at 13,400 × g at 4 °C using a tabletop centrifuge (see Note 5).

The pellet is resuspended by adding approximately 10 volumes of Digestion Buffer and vortexing for a few seconds. The samples are incubated overnight (approximately 16 hours) at 37 °C. Tubes are placed horizontally and swirled or shaken vigorously (approximately 200 rpm).

The samples are washed twice as in Step 8, above, and then resuspended in SDS-Second Ultracentrifugation Buffer, i.e., Wash Buffer also containing 1.30 M sucrose and 1% (w/v) SDS.

The samples are then ultracentrifuged for 30 minutes at 200,000 × g at 15 °C.

Typically, the sample size of the ultracentrifuge tube is 12 mL. The upper 2 mL of the slurry is removed and discarded, and this volume, containing mainly lipids, is replaced with 2 mL of distilled H2O. The mixture is gently and repeatedly (~20 times) pipetted to disperse the solid material. The slurry is then recentrifuged for 30 min at 200,000 × g and at 15 °C. Any additional lipid-rich material is discarded.

The supernatant is then discarded and the pellet gently washed once with distilled H2O, and then twice additionally with PB. In these washes, approximately 10 volumes of liquid is added to the solid; the mixture is then briefly vortexed and then centrifuged for 5 minutes at 13,400 × g. 14.

This isolate is then sonicated for ~ 20 s. in an ice bath for brain parenchyma, or ~ 30 s. for leptomeningeal samples. This step serves to disperse the isolated brain or meningeal material for assays to quantify Aβ. More vigorous sonication is needed to disperse amyloid fibrils for seeding Aβ solutions.

Total protein is measured using any convenient protein assay, such as the BCA assay (Pierce). Aβ content is quantified after digestion with CNBr by LC-MS (unpublished; a similar procedure has been published by Kuo et al., 17). In addition, the isolate is examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which generally shows some collagen fibrils and amorphous material of unknown composition in addition to amyloid fibrils.

The final pellet contains approximately 6- to 12-fold enrichment of amyloid seeding activity. Of the brain extract, in most samples Aβ represents ≤ 1% of the protein mass.

The isolate (see Note 6) can be frozen and stored at –20 °C, or used for seeding. Depending on the quantity of starting material, it may be convenient to make aliquots for freezing. Each aliquot should contain sufficient material to give total protein concentrations of approximately 5 mg/mL when suspended in Seeding Buffer (1.8 mL, as described below).

3.2. Seeded Growth of Amyloid Fibrils

An aliquot of the above material is thawed and suspended in 1.8 ml of Seeding Buffer such that the slurry contains approximately 5 mg/ml of insoluble material.

The suspension is vigorously sonicated (see Note 7). The material is then frozen in liquid nitrogen and thawed to room temperature.

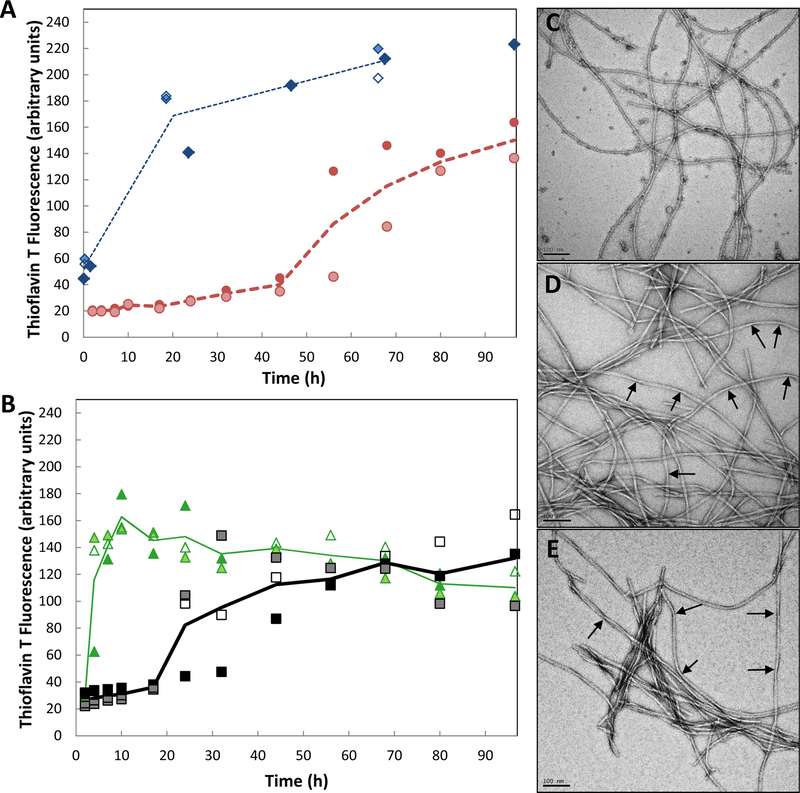

A solution of synthetic or expressed Aβ is then made. In most of our experiments, this is synthetic Aβ40 (see, for example, 12, 13, 18). Comparable results can be obtained using soluble, synthetic Aβ42, and cross-seeding can occur between Aβ40 and Aβ42, albeit at slower rates than self-seeding (Fig. 2). Peptide is dissolved in neat dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a peptide concentration of 6 mM. This is then added to the sonicated brain extract so that the final peptide concentration is 100 μM (i.e., 0.8 mg of Aβ40).

Typically, we used 1 gram of frozen brain tissue and 1 mg of synthetic peptide for seeding experiments.

Fibril growth is monitored by TEM and/or ThT fluorescence (16).

Successful seeding is shown by the appearance of long fibrils in TEM images and/or a rise and plateau in signal in ThT fluorescence (see Note 8) within a few hours.

Fibril growth is allowed to continue for approximately 24 hours (or less, see Note 9), after which fibrils are pelleted by ultracentrifugation and lyophilized for solid- state NMR measurements (see Note 10).

2.

Both synthetic Aβ40 fibrils and Aβ42 fibrils can seed fibrillization of soluble Aβ40. The resulting fibrils contain mainly Aβ40 peptide. A) Unseeded growth of 50 μM Aβ42 ( ) and 100 μM Aβ40 (

) and 100 μM Aβ40 ( ). Note that Aβ42 reaches higher maximum values for ThT fluorescence (arbitrary units), even at half the concentration of Aβ40. B) Growth of Aβ40 fibrils after seeding by 10% preformed Aβ40) (

). Note that Aβ42 reaches higher maximum values for ThT fluorescence (arbitrary units), even at half the concentration of Aβ40. B) Growth of Aβ40 fibrils after seeding by 10% preformed Aβ40) ( ) or Aβ42 (

) or Aβ42 ( ). Assays were performed in duplicate or triplicate; lines demarcate the averages. C) TEM images of Aβ42 fibrils. D) TEM images of Aβ40 fibrils. E) TEM images of fibrils formed using Aβ42 seeds and soluble Aβ40. Arrows point at fibril twists. Scale bar is 100 nm in each image.

). Assays were performed in duplicate or triplicate; lines demarcate the averages. C) TEM images of Aβ42 fibrils. D) TEM images of Aβ40 fibrils. E) TEM images of fibrils formed using Aβ42 seeds and soluble Aβ40. Arrows point at fibril twists. Scale bar is 100 nm in each image.

3.3. Quantitation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in tissue isolates by CNBr Cleavage and LC-MS

An aliquot of brain isolate containing 5–10 μg of protein is dispersed in approximately 25 µL of PB in a conical glass tube.

A fresh solution of CNBr at 5 mg/mL in 88% formic acid is then prepared in a fume hood.

160 μL of the CNBr solution is added to each sample. A sample of 25 µL PB and 160 µL of the CNBr solution is used as a blank.

Samples are covered with parafilm and incubated at 37 °C overnight; tubes are shaken (200 rpm).

Next, 1.4 mL of distilled or Milli-Q H2O is added to each tube, and the material is lyophilized. Since CNBr is volatile, most of the residual CNBr is removed by lyophilization.

After lyophilization, soluble material is dissolved by adding 40 µL of distilled or Milli-Q H2O. This step is repeated once or twice (see Note 11). The liquid is transferred to an Eppendorf tube.

This procedure usually leads to the transfer of some solid material particles were observed in every tube. For this reason, this material is centrifuged for 5 minutes at 13,400 × g and the supernatant is transferred to appropriate vials.

LC-MS should be performed with the next day or so.

It is beyond the scope of this article to consider all of the possibilities for performing LC-MS analyses. We have used the following procedure. We used an Agilent 1290 Infinity UHPLC and 6460 Triple Quad LC/MS instrument, with a Zorbax SB-C18 column with 1.8 μm pores and dimensions of 2.1 × 50 mm, and a 2.1 × 5 mm guard column with the same immobile phase. Solvents A and B were filtered, deionized water with 0.1% (v/v) TFA and solvent B was acetonitrile with 0.1% (v/v) TFA. The column was heated to 40 °C and a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min was used. Peptides were eluted using the following gradient: 5–20% solvent B over 4 minutes, followed by 20–43% over 3 min, followed by 43–65% over 1.4 min, followed by a 6 minute wash of 100% solvent B, followed by a 9 minute equilibration of the column in 5% solvent B.

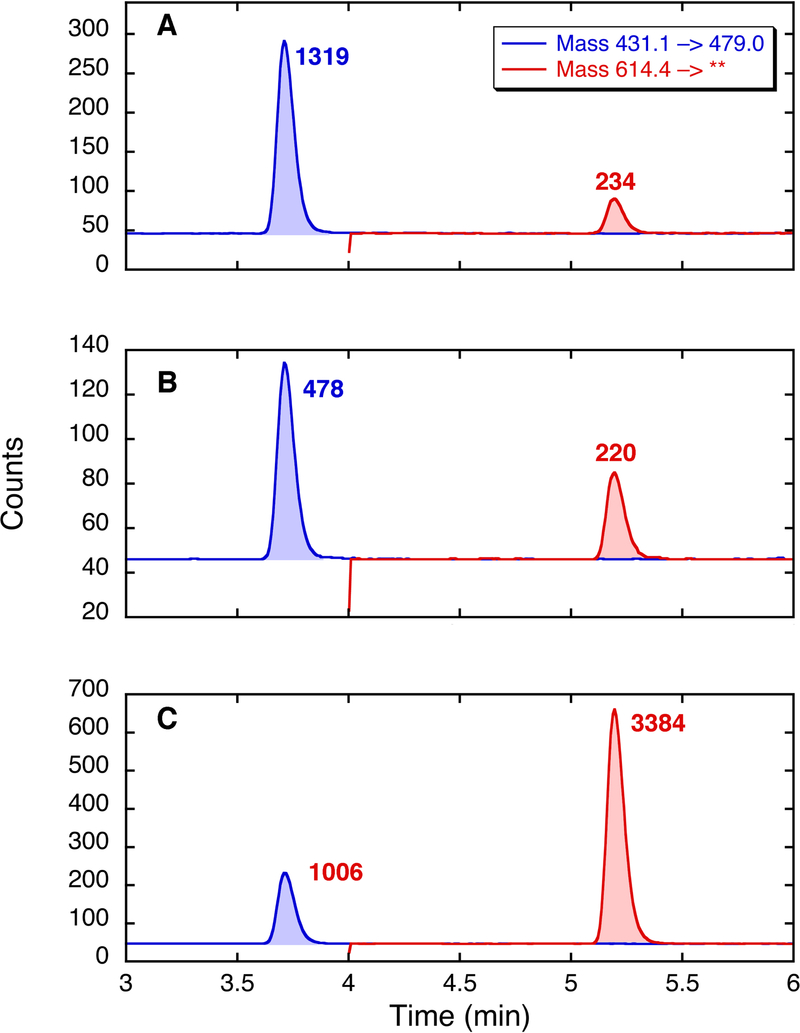

We quantified Aβ(36–40) and Aβ(36–42). Other peptides were present in much lower quantities, but in principle the technique can be scaled up to detect other C-terminal fragments derived from Aβ. Dynamic multiple reaction monitoring was employed to identify and quantitate peaks of these two peptides.

The sequences of these peptides in the underivatized state are VGGVV and VGGVVIA, respectively. Standards were synthesized using FMOC chemistry, and purified by routine reverse-phase HPLC techniques. Standard peptides were quantified using amino acids analysis (19, 20).

Synthetic Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils were also used as controls for the efficiency of CNBr cleavage, recovery of C-terminal peptides, the lyophilization and transfer steps, and LC-MS (see Note 12).

Fig. 4 shows a sample of LC-MS data obtained on two brain samples. In this figure, panel A represents standards, i.e., two synthetic peptides standards, VGGVV and VGGVVIA, which were co-injected. Panels B and C represent analyses of brain amyloid from two different patients, with different ratios of Aβ40 : Aβ42. Ratios of Aβ40 : Aβ42 are calculated using standard curves based on multiple injections of the synthetic peptides on the day of the experiment. (See Note 13.)

4.

LC-MS analysis of peptide standards (A) and two brain samples (B and C) treated as described in the text. The panels are arranged as “chromatographs” in which the x-axis represents ion flow. In each case, the mass range of the 430,3 → 72.1, including the mass of VGGVV (a measure of Aβ40), is shown in blue, and the mass transition 614.4 → 313.2, including the mass of VGGVVIA (a measure of Aβ42), is shown in red. The samples are analyzed by LC-MS in triplicate; the data shown in the figure represent a single determination for each sample.

4. Notes:

All tissues should be treated with proper biosafety procedures. Although in our usual practice brain tissue is stored in a –80 °C freezer, we have observed no difference in quality of NMR spectra of brain-derived material stored at –20 °C.

It is critical that these brains not be put into fixatives such as formalin, which can modify and crosslink proteins. Since fixation is routine for brains at autopsy, and brains in particular may be routinely placed into fixative solutions immediately after removal from the skull, it is often necessary to specify that this tissue is to remain unfixed.

E.g., Sorvall RC 5C Plus centrifuge.

E.g., Beckman XL-80 ultracentrifuge.

E.g., Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415D, for which 13,400 × g is equivalent to 10,000 rpm.

This procedure is designed to be fairly mild. Compared to our earlier procedure (12), the more current protocol (13) decreases the concentration and time of exposure to denaturants (SDS), reduces the time of exposure to collagenase, and eliminates other proteolytic digestion steps. Although collagenase shows significant substrate specificity, this specificity is not absolute. The goal is not to purify the fibrils rigorously, but rather to enrich the tissue isolate in amyloid fibrils. At the concentrations of collagenase and SDS used in this procedure, neither reagent has a significant effect on seeding by synthetic Aβ40 fibrils (see Fig. 3). The addition of collagen (from rat tail tendon, mainly type I collagen) did not have a significant effect on seeding.

Sonifiers differ considerably. In one typical procedure, a Branson S-250A sonifier with a tapered 1/8th inch micro-tip horn is used at lowest power, 10% duty factor, for 10 min. In another procedure, a Branson 450 Sonifier probe sonicator equipped with a 1/8th inch micro-tip, was used at output 7, 80% duty factor, for 8 min. The sample is kept in an ice bath. In addition, we typically include a one min break from sonication between the fourth and fifth minutes in order to avoid overheating the small volume of material.

Fibrils should appear in TEM images within approximately four hours. It is important to compare seeded fibril formation with unseeded control samples. In unseeded fibril growth, few or no fibrils should be apparent by either TEM or ThT fluorescence in the first 24 hours.

Longer incubation times, up to 48 hours, have been used as well. Ideally, (12), fibrils can be prepared in quantities sufficient for solid-state NMR measurements by a single seeding step and an incubation time of ≤ 48 hours. In contrast to longer incubation times or multiple rounds of seeding, a single and short incubation step tends to minimizes the possibility of selective amplification of or suppression of fibril types, and interconversion of fibril types. Whether this can be achieved depends on many factors, especially the quantity of Aβ fibrils in any given brain sample and the quantity of brain material available.

For some solid-state NMR experiments, large quantities of material are needed, and therefore multiple rounds of seeding may be necessary. In such cases, it is important to confirm the reproducibility of fibril morphology by TEM and, when possible, chemical shift measurements from round to round.

The C-terminal peptides of Aβ (i.e., Aβ36-n, where n=39–42) are fully solubilized by this procedure, owing in part to the residual acid in the lyophilized powder.

Typical efficiencies of the CNBr cleavage are 40–50% for synthetic fibrils. These efficiency values almost certainly represent maximal values. Efficiency of cleavage of the CNBr cleavage of any given lot of synthetic Aβ fibrils declined over time, to approximately 25–30% over the course of several months, presumably due to oxidation of Met35 of Aβ in the fibrils.

Standard curves are constructed from pure, synthetic peptides on the day of analyses. For the two peptides, VGGVV and VGGVVIA (indicative of Aβ40 and Aβ42), one typical set of results was as follows. A solution of VGGVV at 8.45 × 10−4 M (0.363 µg/ml) in 0.1% TFA/H2O was diluted with H2O, and 4 μL of the diluted solutions was injected for LC-MS. These solutions gave a curve with the equation y = 2793.7× + 39.35 (× in pmol injected; R = 0.999). A solution of VGGVVIA at 2.38 × 10−4 M (0.146 µg/ml) in 0.1% TFA/H2O was diluted with H2O, and 4 μL of the diluted solutions was injected for LC-MS. These solutions gave a curve with the equation y = 1501.3× + 1.42 (× in pmol injected; R = 0.999). Thus, for the sample shown in Panel B of Fig. 4, with peak size readings of 478 and 220, the Aβ40 : Aβ42 ratio is 0.157 : 0.146 = 1 : 0.93. For the sample shown in Panel C of Fig. 4, with peak size readings of 1006 and 3384, the Aβ40 : Aβ42 ratio is 0.346 : 2.253 = 1 : 6.51.

3.

Collagenase and SDS treatments do not affect the seeding by synthetic Aβ40 fibrils. A) Seeding of solutions of synthetic Aβ40 by 0.5% (w/v) of synthetic Aβ40 fibrils, treated ( ) or not treated previously (

) or not treated previously ( ) with an overnight collagenase digestion. B) Seeding of solutions of synthetic Aβ40 by 2% (w/v) of synthetic Aβ fibrils, treated (

) with an overnight collagenase digestion. B) Seeding of solutions of synthetic Aβ40 by 2% (w/v) of synthetic Aβ fibrils, treated ( ) or not treated previously (

) or not treated previously ( ) with an incubation in 2% (w/v) SDS. Assays were performed in duplicate or triplicate; lines demarcate the averages with ––) and without (– – –) treatments.

) with an incubation in 2% (w/v) SDS. Assays were performed in duplicate or triplicate; lines demarcate the averages with ––) and without (– – –) treatments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, of the National Institutes of Healthm and by N.I.H. grant R01 NS042852 (to S.C.M.).

6. References

- 1.Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Guo ZH, Yau WM, Mattson MP, Tycko R (2005) Self-propagating, molecular-level polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Science 307, 262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benzinger TLS, Gregory DM, Burkoth TS, Miller-Auer H, Lynn DG, Botto RE, Meredith SC (1998) Core Structure of Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid Fibrils Determined by Solid-State NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 95,13407– 134012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tycko R (2014) Physical and structural basis for polymorphism in amyloid fibrils. Protein Sci 23, 1528–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tycko R (2011) Solid-state NMR studies of amyloid fibril structure. Annu Rev Phys Chem 62, 279–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petkova AT, Yau WM, Tycko R (2006) Experimental constraints on quaternary structure in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry 45, 498–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko R (2002) A structural model for Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 99, 16742–16747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paravastu AK, Leapman RD, Yau WM, Tycko R (2008) Molecular structural basis for polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 105, 18349–18354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi K, Takahashi S, Kawai T, Naiki H, Goto Y (2005) Seeding- dependent propagation and maturation of amyloid fibril conformation. J Mol Biol 352, 952–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prusiner SB (2013) Biology and genetics of prions causing neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Genet 47, 601–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyama BH, Weissman JS (2011) Amyloid structure: conformational diversity and consequences. Annu Rev Biochem 80, 557–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tycko R, Wickner RB (2103) Molecular structures of amyloid and prion fibrils: consensus versus controversy. Acc Chem Res 46, 1487–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paravastu AK, Qahwash I, Leapman RD, Meredith SC, Tycko R (2009) Seeded growth of β-amyloid fibrils from Alzheimer’s brain-derived fibrils produces a distinct fibril structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 106, 7443–7448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu JX, Qiang W, Yau WM, Schwieters CD, Meredith SC, Tycko R (2013) Molecular structure of β-amyloid fibrils in Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Cell 154, 1257–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roher AE, Kuo YM (1999) Isolation of amyloid deposits from brain. Methods Enzymol 309, 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roher AE, Lowenson JD, Clarke S, Wolkow C, Wang R, Cotter RJ, Reardon IM, Zurcherneely HA, Heinrikson RL, Ball MJ, Greenberg BD (1993) Structural alterations in the peptide backbone of β-amyloid core protein may account for its deposition and stability in Alzheimers-disease. J Biol Chem 268, 3072–3083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeVine H 3rd. (1999) Quantification of β-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol 309, 274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo YM, Kokjohn TA, Beach TG, Sue LI, Brune D, Lopez JC, Kalback WM, Abramowski D, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M, Roher AE (2001) Comparative analysis of amyloid-beta chemical structure and amyloid plaque morphology of transgenic mouse and Alzheimer’s disease brains. J Biol Chem 276, 12991–12998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sciarretta KL, Gordon DJ, Petkova AT, Tycko R, Meredith SC (2005) Aβ40-lactam(D23/K28) models a conformation highly favorable for nucleation of amyloid. Biochemistry 44, 6003–6014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrikson RL, Meredith SC (1984) Amino acid analysis by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography: precolumn derivatization with phenylisothiocyanate. Analyt Biochem 136, 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mora R, Berndt KD, Tsai H Meredith SC (1988) Quantitation of aspartate and glutamate in HPLC analysis of phenylthiocarbamyl amino acids. Analyt Biochem 172, 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]