Abstract

Disparities in psychosocial adjustment have been identified for lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth, yet research that explores multiple sources of social support among subgroups of LGB youth is sparse. Social support theory is used as a framework to analyze the ways that different sources of support might promote better psychosocial adjustment for LGB youth. Data from a diverse sample among LGB youth (N = 835) were used to understand how social support from a close friend, teachers, classmates, and parents might be differently associated with depression and self-esteem. We found that parent support and its importance to the participant were consistently related to higher self-esteem and lower depression for all youth, except for lesbians for whom no forms of social support were associated with self-esteem. Teacher and classmate support influenced some subgroups more than others. These results provide parents, clinicians, and schools a roadmap to assist youth navigate supports.

Keywords: LGB, social support, parent support, depression, self-esteem

Poor psychosocial adjustment of many lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth is well documented (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2011; Marshal et al., 2011). Theory and related evidence exist to suggest that an explicit focus on the role of social support is warranted. For example, studies have highlighted the benefits of warmth, care, and support from loved ones, especially for LGB youth (Hsieh, 2014). Supportive romantic relationships (Rostosky, Riggle, Gray, & Hatton, 2007), families (Craig & Smith, 2014; Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010), and friendships (Shilo & Savaya, 2012) are associated with better adjustment among LGB youth. Given differences among LGB youth both in reports of psychosocial adjustment (IOM, 2011; Udry & Chantala, 2002) and in potential sources of support (Shilo & Savaya, 2011), the role of distinct forms of social support might differ across sexual identity groups. Emerging contemporary evidence has found that LGB individuals rely more heavily on “chosen families” and friends for everyday social support, such as talking about problems (Frost, Meyer, & Schwartz, 2016). Despite the established association between social support and adjustment for youth, research has not disentangled how multiple sources of social support might be related to psychosocial adjustment among LGB youth.

A disproportionate number of LGB people are at risk for depression and low self-esteem (Herek & Garnets, 2007). One recent meta-analysis found that LGB youth are at significantly higher risk for depression compared with their heterosexual peers (Marshal et al., 2011). LGB youth also report lower self-esteem compared with their heterosexual counterparts, especially those who report victimization at school (Kosciw et al., 2012). In this study, we expand on existing literature by examining how social support from parents, a close friend, teachers, and classmates is related to depression and self-esteem differently among subgroups of LGB adolescents.

Social Support

Social support is strongly related to psychological well-being for adolescents (Brausch & Decker, 2014; Huang, Costeines, Kaufman, & Ayala, 2014). Most youth receive simultaneous support from several different types of interpersonal relationships. Each type of relationship (e.g., family, friend, teacher, classmate) provides distinct sources of resources and specialized support (Kenny, Gallagher, Alvarez-Salvat, & Silsby, 2002). Recent research among heterosexual youth has documented that these distinct sources of social support are differently related to psychosocial adjustment. For example, in one study of 600 young adults surveyed over 4 years, researchers found that different supports had specific implications for self-esteem and depressive mood (Guan & Fuligni, 2015); specifically, for participants with higher-than-average educated parents, increases in peer support were associated with accompanying increases in self-esteem and decreases in depressive symptoms.

It is unclear from previous research whether distinct sources of support vary in their associations with well-being among LGB youth, and whether such patterns may differ among subgroups of sexual minorities (i.e., LGB youth). Previous research suggests that parent (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Ryan et al., 2010; Watson, Barnett, & Russell, 2015), friend (Shilo & Savaya, 2012), teacher (Murdock & Bolch, 2005), and classmate (Kosciw et al., 2012) supports are each essential to successfully cope with negative experiences for LGB youth. However, these forms of support are typically examined separately; this study is one of the first to disentangle the role of multiple sources of social support in the same sample of LGB youth by way of a multifaceted measure of social support (Malecki, Demaray, Elliot, & Nolten 2000). We combine both presence and importance of social support, which has not been applied in studies of LGB youth populations until now.

Parent Support and Psychosocial Adjustment

Families are one of the most important institutions that contribute to the socialization of an adolescent: Both parenting practices and the role of the family system are important elements of adolescent adjustment and development (Parke & Buriel, 2006). Negative parent reactions related to sexual orientation are strongly associated with increases in alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2009). When parents reject their children on the basis of sexual orientation, youth report poorer physical health (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Among LGB young adults, decreased parent support was found to be associated with increases in suicidality and recent drug use (Needham & Austin, 2010).

Not all experiences that LGB youth have with their parents are characterized by stress and compromised adjustment, and family support is protective against negative outcomes for LGB youth. Self-esteem and depression are linked to parent knowledge and degree of acceptance of sexual minority identities: Savin-Williams (1989) found that self-esteem was related to satisfaction with mother and father support and the presence of and contact with parents. The same study also showed differences by sex: For males, mother’s knowledge of a sexual minority identity and infrequent contact with the father were predictive of higher self-esteem, and for sexual minority females, positive relationships with mothers, but not fathers, were predictive of higher self-esteem (Savin-Williams, 1989). In one study of 245 families, there were strong associations between family acceptance, positive self-esteem, and social support for LGB youth (Ryan et al., 2010). Results indicated that family acceptance played an integral role in the mental and emotional health of LGB adolescents. In particular, the way that parents responded to their child’s LGB identity was crucial for healthy development. Another study that used the same sample of 245 families found that parent support was related to life satisfaction, self-esteem, and LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) esteem in young adulthood above and beyond friend and community support (Snapp, Watson, Russell, Diaz, & Ryan, 2015). One other study explored parents’ supportive reactions and the related associations with health among 177 LGB individuals and found that for lesbian and bisexual women, coming out was associated with better health, such as lower levels of depression and past-month illicit drug use (Rothman, Sullivan, Keyes, & Boehmer, 2012). Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, and Malik (2010) also assessed parent support of 98 LGB youth, aged 18 to 21, and found that parent support diminished the effects of emotional distress (Doty et al., 2010). Parent relations and support have clear implications for the well-being of LGB youth, yet previous research has not considered parent support in the context of other established sources of support for LGB youth, such as teachers, classmates, and close friends.

Teacher and Classmate Support and Psychosocial Adjustment

Although families are essential for healthy youth development, experiences at school and among classmates also contribute to development. Schools have long been identified as a setting in which LGBT students experience bullying and a general lack of safety (Kosciw et al., 2012). In response, a growing body of research documents the role of school safety initiatives and the effectiveness of gay–straight alliance clubs in creating positive school climates (e.g., Poteat, Sinclair, DiGiovanni, Koenig, & Russell, 2013), characterized in part by high levels of teacher and classmate support (e.g., Russell, Muraco, Subramaniam, & Laub, 2009). For LGB youth, current research indicates that students find teachers and staff members more supportive than in studies conducted a decade ago (Kosciw et al., 2012). In their national report, Kosciw and colleagues (2012) reported that 95% of students could identify at least one school staff member they perceived to be supportive of LGBT students at their school; a third of students reported that school administrators were supportive of LGBT students. Yet beyond these studies, few scholars have considered distinct sources of support at school. Youth who do not feel a strong sense of connection to classmates at school typically report that they are depressed and lonely (Rubin, Burgess, Kennedy, & Stewart, 2003). One recent study found that LGB students who reported more support from their teachers also reported less victimization, greater self-esteem, higher grade point averages, and fewer missed days of school (Kosciw, Palmer, Kull, & Greytak, 2013). Other studies have investigated support specific to sexual identity. For example, when youth disclosed their sexual minority identities at school and had teachers and classmates who were supportive, they reported higher self-esteem compared with both youth who had “come out” and did not receive support and youth who chose not to come out (Harbeck, 1992).

Friend Support and Psychosocial Adjustment

Friendships support positive adjustment for LGB youth (Rosario et al., 2009), yet some lesbian and gay youth lack friends and feel lonely (Grossman & Kerner, 1998). Some research has found that keeping friends after disclosure of sexual orientation was protective against poor psychosocial adjustment: One study found that lesbian and bisexual girls who disclosed their sexual orientation reported better psychosocial adjustment when they did not lose friends as a result of the disclosure (D’Augelli, 2003). Other studies have linked supportive and accepting friends to better psychosocial adjustment: In a study of 461 self-identified LGB adolescents and young adults, Shilo and Savaya (2011) found that friend support was strongly associated with well-being and had a stronger positive effect on disclosure of sexual orientation compared with parent support and acceptance. In another study, youth who disclosed their sexual orientation to their sexual minority friends received the highest levels of support, which was related to lower levels of mental distress (Doty et al., 2010). In a study of more than 5,000 LGB adolescents, support from friends did not reduce the odds of victimization for LGB youth, regardless of whether the support was in person or online (Ybarra, Mitchell, Palmer, & Reisner, 2015). Taken together, these findings regarding friends—along with parents, teachers, and classmates—highlight the need to further explore how sources of support may be related to psychosocial outcomes for subgroups of sexual minorities.

Current Study

In the current study, we examined whether multiple sources of social support, in the context of perceived importance of that support, were associated with the psychosocial adjustment of LGB youth, and whether there were differences across sex and sexual identities. We measure both the importance and presence of sources of social support for LGB male and females.

Method

Design

Data for the current study come from the first of four waves in a longitudinal panel study of the risk and protective factors of suicide among sexual minority youth. At the first wave, all participants received a cash incentive for their participation. The project was designed to determine the correlates of mental health among sexual minorities, and the current study investigated how one of these potential correlates—social support—might be related to psychosocial adjustment. The institutional review boards of both U.S.-based universities involved approved all study procedures. Youth who met the inclusion criteria were requested to contact the site coordinator in their city and establish an appointment to complete a survey packet. For participants younger than 18 years, youth advocates explained the study to ensure informed consent. A federal certificate of confidentiality was obtained. Thus, parental consent was not required; it was deemed that seeking such consent might put youth at risk of exposing their sexual orientation. Youth completed the survey in 40 to 80 minutes; upon completion, a trained research assistant or site coordinator debriefed participants and assessed for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. In the event participants reported having suicidal thoughts, they were referred to culturally competent mental health services. A protocol was in place if youth reported imminent risk; no such emergency procedures were reported during the study. The assessment procedure consisted of administering a survey packet; data were collected between November 2011 and October 2012.

Measures

Demographic questions

To assess race/ethnicity, participants checked the following options that applied to them: (a) Asian or Asian American, including Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Others; (b) Black or African American; (c) White, Caucasian, Anglo, or European American; (d) American Indian/Native American/Alaskan Native; (e) Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; and (f) Multiracial: Parents are from two or more different racial groups; participants were also given an option to write in their race/ ethnicity.

We asked participants whether their birth sex was male, female, or intersex. Participants were asked to identify their sexual identity: (a) gay; (b) lesbian; (c) bisexual, but mostly gay or lesbian; (d) bisexual; (e) equally gay/ lesbian and heterosexual/straight; (f) bisexual, but mostly heterosexual/straight; (g) heterosexual/straight; (h) questioning/uncertain; and (i) don’t know for sure.

Social support

Support was measured using four subscales of the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS; Malecki et al., 2000): My Parents, My Close Friend, My Teachers, and My Classmates. Four sources of social support were measured separately by creating a mean score from 12 items that asked the degree to which they received support from each source (e.g., my parents “show they are proud of me,” “listen to me when I need to talk,” and “make suggestions when I don’t know what to do.”). Response options were measured on a 6-point scale from 1 (never) to 6 (always). Higher scores correspond to higher levels of perceived support. The importance of social support was measured with 12 items for four domains: parents, classmates, teachers, and a close friend. Participants were asked, “How important to you is it that your ‘parents show they are proud of (you)?’” Items were measured on a 3-point scale, 1 (not at all important) to 3 (very important), and averaged to create separate indexes of perceived importance of social support. To create the final measures of social support, the product of social support and the perceived importance of social support indexes was calculated for each domain: social support from parents (α = .92), classmates (α = .88), teachers (α = .78), and close friends (α = .91). The resulting scale scores ranged from 1 (no support but not important) to 18 (always and very important).

Depression

We measured depression using the 20-item Beck Depression Inventory–Youth (BDI-Y; Beck, Beck, & Jolly, 2001) because it is one of the scales recommended by the American School Counselor Association specifically to examine the relationship between depression and suicidal thoughts, and is one of the most commonly used scales to address such depression in adolescents (see Erford et al., 2011). Participants were given a list of things people think and feel and then asked to choose the responses that correspond to how they feel. Examples of items are as follows: “I think my life is bad,” “I have trouble doing things,” and “I wish that I were dead.” Response options range from 0 (never) to 3 (always). For descriptive analyses, the 20 items were averaged so that higher scores corresponded to greater levels of depression (α = .93).

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was assessed using 10 items of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. As an example, one item was “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.” Response options ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Five items indicating feelings of failure and low self-esteem were reverse coded. For descriptive analyses, the items were summed and averaged (α = .88); higher scores indicated higher levels of self-esteem.

Population

Participants in the original study were 1,061 self-identified lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth and youth with same-sex attraction in three major cities in the Northeast, Southwest, and on the West Coast of the United States. Youth were recruited from community-based agencies and college groups by snowball sampling. We excluded trans* participants and those who identified their sexual identity as “heterosexual” and “questioning/uncertain/don’t know for sure.”

Analysis

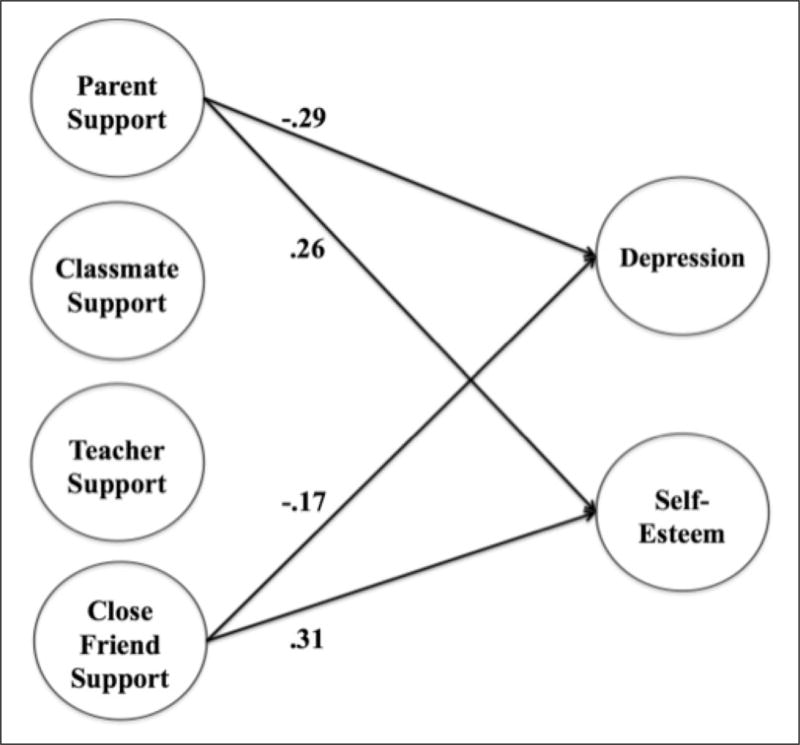

We dummy coded race/ethnicity with White as the reference group. Confirmatory factor analysis was first performed to ensure valid measurement of social support, depression, and self-esteem for all participants. R lavaan was used to conduct a structural equation model (see Figure 1). Three parcels were created for each source of social support (parent, classmate, teacher, and close friend) as well as for depression and self-esteem. An Item-to-Construct Balance Model was utilized to parcel; thus, the highest loaded item was grouped with the lowest loaded item to create the first parcel, and so on (for more information regarding parceling, see Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). An omnibus test revealed that there were differences between the four subgroups: gay, lesbian, bisexual male, and bisexual female. Multiple group comparisons were assessed to see whether the significance of the beta coefficients for the pathways differed across models.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model that presents the associations between social support and mental health for full sample of LGB youth (N = 835).

Note. Three parcels were created for each source of social support and for depression and self-esteem using an Item-to-Construct Balance Model; model fit was good.

Results

Of the included participants in the current study (N = 835 self-identified LGB youth ages 15 to 21 at the time of recruitment, M = 18.77, SD = 1.85), 31.8% identified as gay males, 22.2% as lesbian or gay-identified females, 15.3% as bisexual males, and 30.7% as bisexual females. Using current federal reporting guidelines, 39.2% were of Hispanic or Latino background. Regarding race, 20.8% were White, 24.2% Black or African American, 4.8% Asian, 2.9% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 0.8% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 22.4% more than one race, and 24.0% did not report their race.

Table 1 provides the descriptive information for key study variables, and Table 2 displays the correlations. As a whole, participants reported receiving more friend support than parent, classmate, and teacher support. Sources of social support were generally moderately correlated across each source of social support, with the exception of supports within school, which were strongly correlated (teachers and classmates, r = .54).

Table 1.

Descriptives (Means) of Study Variables for the Overall Sample and Separate for Gays, Lesbians, and Bisexuals by Gender.

| Study Variables | Overall sample (N = 835) |

Gay male (n = 266) |

Lesbian female (n = 185) |

Bisexual male (n = 128) |

Bisexual female (n = 256) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18.77 | 19.30 | 18.90 | 18.79 | 18.14 |

| Depression | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.93 |

| Self-esteem | 3.08 | 3.18 | 3.12 | 3.06 | 2.99 |

| Parent Support × Importance | 8.65 | 9.00 | 8.76 | 8.87 | 8.23 |

| Classmate Support × Importance | 7.19 | 7.72 | 6.86 | 7.13 | 7.12 |

| Teacher Support × Importance | 9.80 | 10.67 | 9.64 | 9.52 | 9.33 |

| Close Friend Support × Importance | 13.07 | 13.39 | 12.84 | 12.44 | 13.31 |

Note. All values represent the mean score of each variable. Mean scores presented for outcome variables; scores on support×importance variables range from 0 (no support but not important) to 18 (most support and very important).

Table 2.

Bivariate Pearson’s Correlations of Independent and Dependent Variables.

| Study Variables | Depression | Self-esteem | Parent Support × Importance |

Classmate Support × Importance |

Teacher Support × Importance |

Close Friend Support × Importance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||||

| 1. | Depression | 1.00 | |||||

| 2. | Self-esteem | −.66** | 1.00 | ||||

| Independent variables | |||||||

| 3. | Parent Support × Importance | −.37** | .35** | 1.00 | |||

| 4. | Classmate Support × Importance | −.27** | .27** | .35** | 1.00 | ||

| 5. | Teacher Support × Importance | −.21** | .24* | .36** | .52** | 1.00 | |

| 6. | Close Friend Support × Importance | −.19** | .19* | .35** | .33** | .33** | 1.00 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

The Presence and Importance of Social Support for LGB Youth

Figure 1 displays the results of the structural equation model for all participants. Model fit was good (comparative fit index [CFI] = .995; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .028); thus, no alternative models were examined. The loadings for the three parcels on each social support construct were good and ranged from .90 to .96. The loadings for self-esteem ranged from .71 to .89 and depression from .88 to .93 (see Figure 1). There was no significant difference (p = .30) between both the weak and strong invariance tests across gay, bisexual, and lesbian subgroups; thus, the investigation of differences in the relationship between social support and psychosocial adjustment across subgroups was permissible. To do this, all regression pathways were constrained across groups to estimate a base model to compare each subsequent subgroup model. Next, individual pathways were constrained separately across groups, and fit statistics were compared with the base model to determine whether there were significant differences. For example, “parent support and importance” were constrained, while other pathways were freely estimated and the fit statistic was compared with the base model.

Even though close friend support showed weak correlations compared with measures of psychosocial adjustment compared with parent support, both close friends and parents appeared as the critical predictors when considered in the multivariate analyses. The results indicate that the presence and importance of parent support were associated with moderately less depression for the entire sample. In addition, the presence and importance of close friend support were negatively associated with depression (although the effect size is weak). Measures of classmate and teacher support were not associated with depression. Regarding self-esteem, there was a notably similar pattern: Presence and support from parents and close friends were both positively related to self-esteem. As was true for depression, the relation between classmate and teacher support was not associated with self-esteem scores.

Differences Among LGB Youth

The model fit indices indicated that social support worked equally well across sex and sexual identity groups. Differences in associations between presence/ importance of sources of support and psychosocial adjustment were found across groups. Table 3 displays the standardized betas for each pathway (e.g., depression on parent support) for each of the four subgroups in the study.

Table 3.

Associations Between Type of Support Source and Mental Health Outcome by Sexual Orientation.

| Study Variables | Overall (N = 835) |

Gay (n = 266) |

Lesbian (n = 185) |

Bisexual male (n = 128) |

Bisexual female (n = 256) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem | |||||

| Parent support | .26** | .21** | .15 | .41** | .37** |

| Teacher support | .10** | .13** | −.01 | .07** | .02** |

| Classmate support | .10** | .10** | .21 | .02** | .24** |

| Close friend support | .31** | .17** | .16 | −.06** | .31** |

| Depression | |||||

| Parent support | −.29** | −.22*** | −.18* | −.39*** | −.22** |

| Teacher support | −.01** | .04** | .08 | −.12** | −.03** |

| Classmate support | −.07** | −.10** | −.14* | .08** | −.14** |

| Close friend support | −.17** | −.12** | −.20* | −.04** | −.12** |

Note. Numbers presented are standardized beta coefficients; each form of social support (parent, classmate, teacher, and close friend) is a product of the degree of support received (6-point scale) and the importance of the support (3-point scale).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

For gay male youth, only parent support was associated with less depression. Parent and close friend support were associated with higher self-esteem for gay youth. Parent, classmate, and close friend support were related to less depression for lesbian youth, but no support sources were associated with self-esteem for lesbian youth. Among bisexual youth, parent support was associated with less depression and higher self-esteem for males. For bisexual females, close friend support was associated with less depression, and parent support was associated with higher self-esteem.

Discussion

This study contributes a deeper understanding of psychosocial adjustment and the role of social support for sexual minorities by elucidating different patterns of support for gays, lesbians, and bisexuals. Not all sources of social support were equally important for LGB youths’ psychosocial adjustment; instead, support sources operated differently among sexual minority subgroups, which suggests that there is no monolithic approach to dealing with LGB adolescents’ adjustment at home and school. Overall, the patterns of social support corroborated the findings of previous contemporary research: LGB youth rated friend support as most prevalent and important (similar to the findings of Doty et al., 2010). Nevertheless, despite lower ratings of importance compared with other sources, support from parents emerged as a consistent and strong correlate of psychosocial adjustment.

A growing body of research has highlighted the importance of school experiences for LGB youth (Kosciw et al., 2012; Poteat, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009), yet teacher support was not significantly associated with depression and self-esteem for LGB youth in this sample. Clearly, more research can continue to include teachers, classmates, and administrators (see Ryan et al., 2010; Shilo & Savaya, 2011) to better understand the role of school support and psychosocial adjustment. For example, we should work to develop appropriate instruments that can measure the unique contribution of supportive schools in the overall well-being of LGB students.

In this study, no sources of social support were protective against lower self-esteem for lesbians. However, three social support sources (parent, classmate, and close friend) were significantly associated with less depression for lesbians. This has implications for how we consider the processes that may differently influence depression and self-esteem for subgroups of sexual minority youth. This finding contradicts previous literature that has implicated friends as especially important for women because of the void they may fill that exists from compromised support from family and community members (Jordan & Deluty, 1998). The finding also contradicts an early study that showed that the well-being of lesbian women was associated with interpersonal support that specifically reassured their worth as lesbian women (Wayment & Peplau, 1995). More recent research has found that partner support—but not family support—is related to relationship quality for same-sex couples (Graham & Barnow, 2013); however, in a study of 255 multiethnic high school girls, scholars found that family support was associated with better school performance (Craig & Smith, 2014). We are not led to believe that supportive interpersonal relationships make no difference for lesbians’ self-esteem; however, it is compelling that self-esteem for lesbians was not clearly associated with social support—whereas depression was—to the degree found with gay and bisexual participants.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study relied on cross-sectional data; therefore, we cannot conclude whether the support sources are directly predicting psychosocial adjustment— The opposite could be true. We would be able to take earlier reports of depression and self-esteem into consideration with longitudinal data. The social support scale used did not measure support related to the youths’ sexual identity. Previous research has noted the particular importance of measuring social support specific to youths’ sexual identity (see Doty et al., 2010), which suggests that this specific support could play a distinct role in adjustment and mental health; thus, future studies should study multiple types of social support. Specifically, future studies of LGB youth could compare the distinct role of general versus LGB-specific social support in promoting psychosocial adjustment. Other limitations included a data set that was based entirely on youth self-reports, potential confounds with a sample that consisted of LGB youth who were willing to participate in a study on mental health, and issues of generalizability by virtue of the sampling of three major metropolitan cities across the United States. For example, youth who participate in community and college groups may be more likely to have disclosed their sexual identity to others. Future studies should consider contexts of “outness” and how this is related to social support.

This study focused on measures of social support. Two domains of social support have been explored in previous literature: instrumental (advice giving) and social-emotional support (warmth and care); future work should consider both domains. Previous research has shown that LGB youth perceive instrumental support from both LGB and heterosexual friends and parents (Munoz-Plaza, Quinn, & Rounds, 2002), and this support is related to well-being. Furthermore, studies of LGB youth have documented rejection from the parental home, a clear withdrawal of instrumental support, as an extreme form of parental rejection and a critical risk factor for LGB youth (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2012). Future studies should also consider different types of social support and the specific facets of this support, such as monetary assistance, emotional support, advice from LGB elders and role models, and relational support.

Little research has specifically considered the role of close friends, which appears to be a crucial resource for bolstering LGB youth mental health. Given the importance of close friends, a domain of support that has received relatively little attention has been romantic relationships as potential supportive buffers. The few studies that have explored romantic relationships among LGB youth (or samples more generally) have reported mixed findings (see Russell, Watson, & Muraco, 2011). Scholars should continue to explore the potential role that same-sex partners—disclosed to others and not—might have on psychosocial adjustment for LGB youth.

Future research should continue to consider differences across sexual identities to reveal potential important differences in psychosocial adjustment and the role of social support. In addition, researchers should utilize longitudinal data to understand how support might affect LGB youth over time. There are many unique factors pertaining to the LGB experience that scholars must measure when studying LGB youth: For example, the age that youth disclose their sexual identity is relevant to the implications of interpersonal support, acceptance and rejection, and experiences of psychosocial adjustment. Scholars must also consider support from siblings, family structure, and targets of disclosure (i.e., whom youth have disclosed their identity to; see Watson, Wheldon, & Russell, 2015), and measures specific to sexual identity, such as parent acceptance of one’s sexual identity.

Regarding practice and policy, our results show that counselors and mental health professionals should not assume all sources of social support operate similarly across subgroups of sexual minorities. Clearly, support from friends is important for LGB and all youth, and our results suggest that settings where LGB youth may find supportive friends are important contexts to nurture and support, whether in schools (such as gay–straight alliance clubs) or community-based organizations. For clinicians and others working directly with youth, we note that youth themselves may not be conscious of how important their family relations (with parents or guardians) may be to their well-being. When working with youth, we suggest that clinicians work with youth to understand which forms of support are most important and accessible to them, while understanding possible differences in the salience and meaning of different sources of support for young lesbians, gays, and bisexuals.

In summary, this study advances our knowledge about sources of social support and their relation to psychosocial adjustment for LGB youth. Prior to this study, social support research often considered LGB youth a monolithic population, and most literature focused on a limited number of sources of support. We importantly addressed this shortcoming by examining how different sources of support were related to psychosocial adjustment for LGB youth separately by sexual identity and birth sex. By providing a more nuanced depiction of how different supports for subgroups of LGB youth are related to psychosocial adjustment, we have enhanced the ability for counselors and health professionals to better serve lesbians, gays, and bisexuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amanda Pollitt for her assistance in the preparation of this article, and the youth who participated in the survey used in these analyses.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors acknowledge support for this research from a National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship awarded to the first author (Grant DGE-1143953) and from the Fitch Nesbitt Endowment (Norton School, University of Arizona) in support of the third author. This research uses data from the Risk and Protective Factors for Suicide Among Sexual Minority Youth study, designed by Arnold H. Grossman and Stephen T. Russell, and supported by Award Number R01MH091212 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Biographies

Ryan J. Watson is an Assistant Professor at the University of Connecticut in the department of Human Development and Family Studies. His scholarly interests include the study of LGBTQ youth, their mental health, academic success, family experiences, and other protective factors.

Arnold H. Grossman is a Professor of Applied Psychology in the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, & Human Development at New York University. The focus of his current research program is examining the risk and protective factors for suicide among sexual minority youth with the aim of learning the relative contributions of psychological, individual, and interpersonal factors.

Stephen T. Russell, PhD, is a Priscilla Pond Flawn Regents Professor in Child Development at the University of Texas at Austin. He studies adolescent development, with an emphasis on adolescent sexuality, LGBT youth, and parent-adolescent relationships.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Beck JS, Beck AT, Jolly J. Manual for the Beck Youth Inventories of emotional and social impairment. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brausch AM, Decker KM. Self-esteem and social support as moderators of depression, body image, and disordered eating for suicidal ideation in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:779–789. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9822-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, Smith MS. The impact of perceived discrimination and social support on the school performance of multiethnic sexual minority youth. Youth & Society. 2014;46:30–50. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11424915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Lesbian and bisexual female youths aged 14 to 21: Developmental challenges and victimization experiences. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7(4):9–29. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty ND, Willoughby BL, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erford BT, Erford BM, Lattanzi G, Weller J, Schein H, Wolf E, Peacock E. Counseling outcomes from 1990 to 2008 for school-age youth with depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2011;89:439–457. [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH, Schwartz S. Social support networks among diverse sexual minority populations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:91–102. doi: 10.1037/ort0000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM, Barnow ZB. Stress and social support in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual couples: Direct effects and buffering models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:569–578. doi: 10.1037/a0033420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, Kerner M. Self-esteem and supportiveness as predictors of emotional distress in gay male and lesbian youth. Journal of Homosexuality. 1998;35(2):25–37. doi: 10.1300/J082v35n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan SSA, Fuligni AJ. Changes in parent, sibling, and peer support during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2015;26:286–299. doi: 10.1111/jora.12191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harbeck KM. Gay and lesbian educators: Past history/future prospects. Journal of Homosexuality. 1992;22(3–4):121–140. doi: 10.1300/J082v22n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Garnets LD. Sexual orientation and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D’Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:65–74. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.1.65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N. Explaining the mental health disparity by sexual orientation: The importance of social resources. Society and Mental Health. 2014;4:129–146. doi: 10.1177/2156869314524959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Costeines J, Kaufman JS, Ayala C. Parenting stress, social support, and depression for ethnic minority adolescent mothers: Impact on child development. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23:255–262. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9807-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KM, Deluty RH. Coming out for lesbian women: Its relation to anxiety, positive affectivity, self-esteem, and social support. Journal of Homosexuality. 1998;35(2):41–63. doi: 10.1300/J082v35n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny ME, Gallagher LA, Alvarez-Salvat R, Silsby J. Sources of support and psychological distress among academically successful inner-city youth. Adolescence. 2002;37(145):161–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA, Gay L. The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, Kull RM, Greytak EA. The effect of negative school climate on academic outcomes for LGBT youth and the role of in-school supports. Journal of School Violence. 2013;12:45–63. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2012.732546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki CK, Demaray MK, Elliott SN, Nolten PW. The Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Brent DA. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Plaza C, Quinn SC, Rounds KA. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students: Perceived social support in the high school environment. The High School Journal. 2002;85(4):52–63. doi: 10.1353/hsj.2002.0011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock TB, Bolch MB. Risk and protective factors for poor school adjustment in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) high school youth: Variable and person-centered analyses. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42:159–172. doi: 10.1002/pits.20054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL, Austin EL. Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:1189–1198. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 3: Social, emotional, and personality development. 6. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2006. pp. 429–504. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL, Koenig BW. Willingness to remain friends and attend school with lesbian and gay peers: Relational expressions of prejudice among heterosexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:952–962. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Sinclair KO, DiGiovanni CD, Koenig BW, Russell ST. Gay-straight alliances are associated with student health: A multi-school comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2013;23:319–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00832.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Critical role of disclosure relations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:175–184. doi: 10.1037/a0014284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Risk factors for homelessness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A developmental milestone approach. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Riggle ED, Gray BE, Hatton RL. Minority stress experiences in committed same-sex couple relationships. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38:392–400. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.38.4.392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Sullivan M, Keyes S, Boehmer U. Parents’ supportive reactions to sexual orientation disclosure associated with better health: Results from a population-based survey of LGB adults in Massachusetts. Journal of Homosexuality. 2012;59:186–200. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.648878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Kennedy AE, Stewart SL. Social withdrawal in childhood. In: Mash J, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 372–406. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Muraco A, Subramaniam A, Laub C. Youth empowerment and high school gay-straight alliances. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:891–903. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9382-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Watson RJ, Muraco JA. Development of same-sex intimate relationships. In: Laursen B, Collins AW, editors. Relationship pathways: From adolescence to young adulthood. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2011. pp. 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;23:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Parental influences on the self-esteem of gay and lesbian youths: A reflected appraisals model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1989;17:93–110. doi: 10.1300/J082v17n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo G, Savaya R. Effects of family and friend support on LGB youths’ mental health and sexual orientation milestones. Family Relations. 2011;60:318–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00648.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo G, Savaya R. Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and young adults: Differential effects of age gender, religiosity, and sexual orientation. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22:310–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00772.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snapp SD, Watson RJ, Russell ST, Diaz RM, Ryan C. Social support networks for LGBT young adults: Low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Family Relations. 2015;64:420–430. doi: 10.1111/fare.12124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udry JR, Chantala K. Risk assessment of adolescents with same-sex relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:84–92. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Barnett MA, Russell ST. Parent support matters for the educational success of sexual minorities. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2015;12:188–202. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2015.1028694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Wheldon CW, Russell ST. How does sexual identity disclosure impact school experiences? Journal of LGBT Youth. 2015;12:385–396. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2015.1077764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wayment HA, Peplau LA. Social support and well-being among lesbian and heterosexual women: A structural modeling approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:1189–1199. doi: 10.1177/01461672952111007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ, Palmer NA, Reisner SL. Online social support as a buffer against online and offline peer and sexual victimization among U.S. LGBT and non-LGBT youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;39:123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]