Abstract

Objectives

To systematically examine the evidence of harms and benefits relating to time spent on screens for children and young people’s (CYP) health and well-being, to inform policy.

Methods

Systematic review of reviews undertaken to answer the question ‘What is the evidence for health and well-being effects of screentime in children and adolescents (CYP)?’ Electronic databases were searched for systematic reviews in February 2018. Eligible reviews reported associations between time on screens (screentime; any type) and any health/well-being outcome in CYP. Quality of reviews was assessed and strength of evidence across reviews evaluated.

Results

13 reviews were identified (1 high quality, 9 medium and 3 low quality). 6 addressed body composition; 3 diet/energy intake; 7 mental health; 4 cardiovascular risk; 4 for fitness; 3 for sleep; 1 pain; 1 asthma. We found moderately strong evidence for associations between screentime and greater obesity/adiposity and higher depressive symptoms; moderate evidence for an association between screentime and higher energy intake, less healthy diet quality and poorer quality of life. There was weak evidence for associations of screentime with behaviour problems, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, poorer self-esteem, poorer well-being and poorer psychosocial health, metabolic syndrome, poorer cardiorespiratory fitness, poorer cognitive development and lower educational attainments and poor sleep outcomes. There was no or insufficient evidence for an association of screentime with eating disorders or suicidal ideation, individual cardiovascular risk factors, asthma prevalence or pain. Evidence for threshold effects was weak. We found weak evidence that small amounts of daily screen use is not harmful and may have some benefits.

Conclusions

There is evidence that higher levels of screentime is associated with a variety of health harms for CYP, with evidence strongest for adiposity, unhealthy diet, depressive symptoms and quality of life. Evidence to guide policy on safe CYP screentime exposure is limited.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018089483.

Keywords: screentime, chil health, obesity, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Undertook a systematic review of reviews in multiple electronic databases using a prespecified methodology.

Included only studies that directly reported screentime separately from other sedentary behaviours.

Used assessment of review quality and weight of supportive evidence to assign strength of evidence to findings.

Quality of included reviews was predominantly moderate or low, dominated by studies of television screentime, with screentime largely self-reported.

Data on mobile screen use was extremely limited and our review did not address the content or context of screen viewing.

Introduction

The screen, whether it is computer, mobile, tablet or television, is a symbol of our modern age. For our children, the ‘digital natives’ who have grown up surrounded by digital information and entertainment on screens, time on screens (screentime) is a major part of contemporary life.

However, there have been growing concerns about the impact of screens on children and young people’s (CYP) health. There is evidence that screentime is associated with obesity, with suggested mechanisms an increase in energy intake,1 the displacement of time available for physical activity2 or more directly through reduction in metabolic rate.3 There is also evidence that high screentime is associated with deleterious effects on irritability, low mood and cognitive and socioemotional development, leading to poor educational performance.4

Because of these concerns, expert groups have suggested controlling screentime for children. The American Academy of Pediatrics in 2016 recommended limiting screentime for children aged 2–5years to 1 hour/day of high-quality programmes and for parents to limit screentime in agreement with CYP 6 years and older.5 The Canadian Paediatric Society issued similar guidelines in 2017.6

However, there has been criticism of professional guidelines as non-evidenced-based,7 as evidence for an impact of screentime on health is inconsistent, with systematic reviews showing inconsistent findings.8–11 This may in part be due to failure to separate screentime from non-screen sedentary behaviours characterised by low physical movement and energy expenditure. It may also be due to a failure to separate the sedentary elements of screentime from the content watched on screens. Others have argued that screen-based digital media have potential significant health, social and cognitive benefits and that harms are overstated. A prominent group of scientists recently argued that messages that screens are inherently harmful is simply not supported by solid research and evidence.12 Others have noted that education and industry sectors frequently promote expanded use of digital devices by CYP.13

Our aim was to systematically examine the evidence on the effects of time spent using screens on health and well-being among CYP. Systematic reviews of reviews (RoR or umbrella reviews) are particularly suited to quickly collating the strength of evidence across a very broad area to guide policy. We therefore undertook an RoR of the effects of screentime of any type on CYP health and well-being outcomes.

Methods

We undertook a systematic review of published systematic reviews, reporting methods and findings using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist.14 The review was registered with the PROSPERO registry of systematic reviews (registration number CRD42018089483).

Review question

Our review question was ‘What is the evidence for health and well-being effects of screentime in children and adolescents?’

Search strategy

We searched electronic databases (Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL) in February 2018. We used the search terms in Medline as follows: ‘(child OR teenager OR adolescent OR youth) AND (screen time OR television OR computer OR sedentary behaviour OR sedentary activity) AND health’, with publication type limited to ‘systematic review, with or without meta-analysis’. Similar search terms were used in the other databases. We did not limit studies by date or language. Identified relevant reviews were hand-searched for additional likely references.

Eligibility criteria

We only included systematic reviews which fulfilled the following eligibility criteria:

Systematically searched and reviewed the literature using prespecified protocols.

Examined children or adolescents from 0 to 18 years. Studies with a wider age range which provided data on children/adolescents separately were eligible.

Assessed and reported screentime, that is, time spent on screens of any type, including self-report or measured/observed measures.

Examined health and well-being impacts on children or adolescents.

We excluded reviews in which screentime was not defined adequately or where time on screens was not separated from other forms of sedentary behaviour, for example, sitting while talking/homework/reading, time spent in a car, etc. Where reviews examined overall sedentary behaviour but reported findings for screentime separately to other forms of sedentary behaviour, these were included. However, reviews that did not separate screentime from other sedentary behaviour were not included. Where authors updated a review which included all previous studies, we only included the later review to avoid duplication.

Study selection

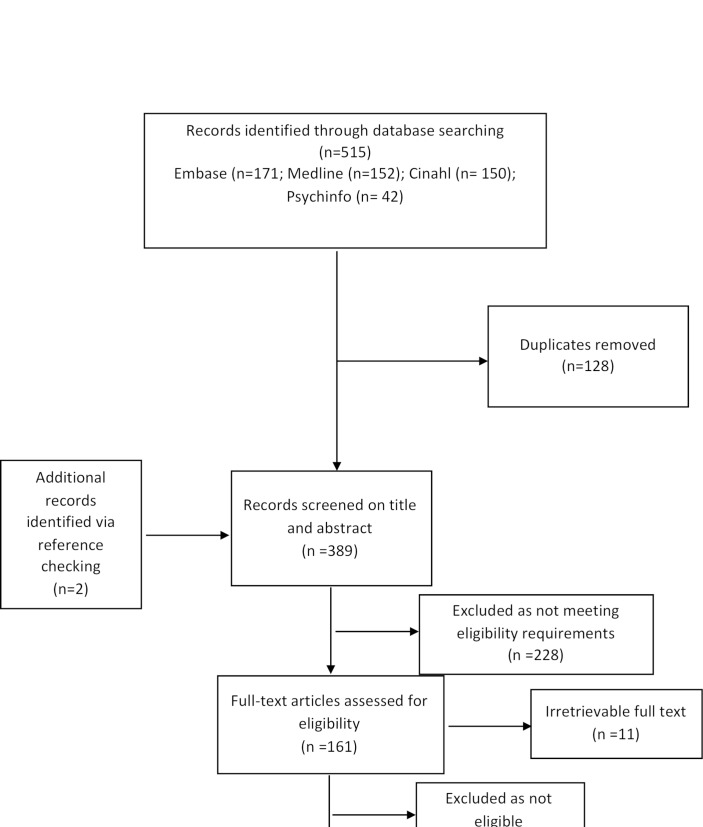

A flow chart of study identification and selection is shown in figure 1. Titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially eligible articles identified after removal of duplicates. The abstracts of 389 articles were reviewed and 161 potentially eligible articles were identified which appeared to meet the eligibility criteria. After review of full text to determine final eligibility, 13 reviews are included in this review. Characteristics of the included reviews are shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author | Age | Outcome measures | Meta-analysis | Studies (n, CS, LS, RCT, N of subjects) |

% duplicate studies | Narrative findings | Findings of meta-analysis |

| Pearson and Biddle19 | C< 11 y; A: 12–18 y | Dietary intake; assessed largely through food frequency questionnaires | No | n=53; 19 in C and 26 in Ad; largely CS; 5 LS in C and 5 LS in Ad. Total N not reported. | 14.6% | C (<12 y): TVST – assoc. with fruit, vegetable consumption; + assoc. with energy-dense snack consumption, fast food consumption, energy-dense drinks, total energy intake, percentage energy from fat. Ad: ST – assoc. with fruit, vegetable, FV, fibre consumption; + assoc. energy-dense snack, fast food, fried food consumption, energy dense drink, total energy intake, percentage energy from fat, total fat. |

C: strengths of assoc. were mainly small to moderate (no exact values given); Ad: strength of assoc. was small to moderate for energy-dense drinks and snacks (no exact values given). |

| LeBlanc et al 18 | 0–4 y | Adiposity (n=11), psychosocial health (n=6), cognitive development (n=8 studies). No studies identified of bone mass, motor development or cardiometabolic health | No | n=23. N=22 417. |

13.0% | Infants: TVST elicited no benefits and may be harmful to cognitive development; increased TVST assoc. with unfavourable adiposity. Toddlers: TVST has – impact on adiposity, cognitive development, – affected psychosocial health Preschoolers: TVST – impact on adiposity; evidence between increased TV and decreases scores on measures of psychosocial health; – relationship between TVV and cognitive development |

|

| Costigan et al 8 | 12–18 y | Physical, psychosocial and/or behavioural health outcomes | No | n=33; 25 CS, 8 LS. | 21.2% | ST + assoc. with weight status, neck/shoulder/lower back pain, backache/headache, sleep problems and depressive symptoms; − assoc. with perceived health and healthy dietary behaviour. |

|

| Tremblay et al 10 | 5–17 y | Body composition, physical fitness, metabolic syndrome (MetS), cardiovascular risk, self-esteem, prosocial behaviour, academic performance | Yes | n=232; 8 RCTs, 10 intervention studies, 37 LS and 177 CS. N= 983 840. |

2.2% | +assoc. between adiposity and TVST; assoc. between ST and higher cholesterol and blood pressure, haemoglobin A1c and insulin insensitivity; − relationship between ST and self-esteem; >2 hours/day ST assoc. with lower cardiorespiratory fitness. |

TVST and BMI was the only area where data allowed meta-analysis; 4 RCTs included in the meta-analysis: decreased TVST assoc. with decrease in BMI (−0.89 kg/m2 (95% CI −1.467 to −0.11, p=0.01). |

| Suchert et al 10 | 5–18 y | Depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, internalising problems, self-esteem, eating disorder symptoms, hyperactivity and inattention problems, well-being and quality of life (QoL) | No | n=91; 73 CS, 16 LS, 2 RCT. N not reported. | 7.7% | + assoc. between ST and hyperactivity/inattention problems, internalising problems, poorer psychological well-being and perceived QoL. Indeterminate assoc. between SBB and depressive and anxiety symptoms, self-esteem and eating disorder symptoms. | |

| van Ekris et al 11 | <18 y | Anthropometrics, cardiometabolic risk, blood pressure, fitness, other biomedical health indicators | Yes | n=109; N=24 257 for MA of TVV and BMI from 9 prospective cohorts. N=6971 for MA of computer screen viewing and BMI from 5 prospective cohorts. | 5.2% | + relationship between TVST and overweight/obesity incidence and overweight/obesity incidence; NoE for relationship between computer use/game time with BMI/BMI z-score or WC/WC z-score; + relationship between ST and BMI/BMI z-score and overweight/obesity. NoE for relationship between ST and triglycerides and glucose, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, ratio of total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and systolic and diastolic blood pressure; - relationship between TVST and cardiorespiratory fitness/VO2max; InE with strength and being unfit, cardiorespiratory fitness/VO2max and metabolic risk z-scores, asthma and bone mass indicators. |

MA: BMI at follow-up was not significantly associated with each additional hour of TV viewing (β=0.01, 95% CI (−0.002 to 0.02)) or computer use (β=0.00, 95% CI (-0.004 to 0.01)) per day, with high heterogeneity in each analysis. Adjustment for physical activity or diet did not change findings. |

| Carson et al 17 | 5–17 y | Body composition, MetS/cardiovascular disease risk factors, academic achievement, fitness, self-esteem | No | n=235; 1 RCT, 1 cross-over trial, 49 LS, 5 CC and 179 CS. 35 used accelerometer measures of SB. N not stated. |

3.5% | Higher ST assoc. with unfavourable body composition, overweight/obese and with clustered risk factor score and lower cardiorespiratory fitness, unfavourable measures of behaviour, lower self-esteem (TVST); inconsistent findings for assoc. with lower academic attainment. | |

| Hoare et al 20 | 10–19 y | Depressive symptomatology, anxiety symptomatology, self-esteem, suicide ideation, other mental health indicators | No | n=32; 1 RCT, 6 LS, 24 CS. |

21.9% | + Relationship between ST and depressive symptomatology, psychological distress and ST duration and severity of anxiety symptoms. + Relationship between low self-esteem and screen time. InE for relationship between ST and suicidal ideation. | |

| Duch et al 9 | <3 y | Biological and demographic factors, family biological and demographic factors, family structure factors, behavioural factors, structural environmental factors | No | n=29; 18 CS, 10 LS, 1 RCT. N not stated. |

3.5% | + Assoc. between ST and age and BMI. InE on ST and sleep duration and crying duration. | |

| Marsh et al 1 | 5–24 y | Energy intake measured objectively in experimental studies using an experimental meal during two exposure scenarios | No | n=10; 8 RCT and 2 quasi-experimental studies. |

0 | ST (in the absence of food advertising) assoc. with increased dietary intake; TVST increases intake of very palpable energy-dense foods; stimulatory effects of TVST on intake were stronger in overweight/obese C than those of normal weight | |

| Hale and Guan24 | 5–17 y | Sleep outcomes | No | n=67; 3 RCT. | 0 | Assoc. with at least one of the sleep outcomes (delayed bedtime, shortened total sleep time, daytime tiredness, sleep onset latency) was found for computer use, video gaming, mobile device, unspecified ST. | |

| Goncalves de Oliveira et al 23 | 10–19 y | MetS | Yes. ST dichotomised as ≤2 h vs >2 h for analyses | n=21; 9 examined ST, 8 CS, 1 CC. N=8680. |

0 | Inconclusive evidence for the assoc. of ST or TVST with presence of the MetS. | Significant assoc. was not identified between ST and MetS; OR for MetS in relation to >2 h ST=1.20 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.59), p=0.20, n=3881, studies =6, I2=37%). Subgroup analysis: no significant assoc. between ST and MetS through the whole week (OR=1.03 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.42), p=0.84, n=2261, studies=4, I2=24%); however, there was a significant assoc. between weekend ST and MetS (OR=2.05 (95% CI 1.13 to 3.73), p=0.02, n=1620 studies=2, I2=0%). |

| Wu et al 22 | 3–18 y | Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) | Yes. ST dichotomised as <2–2.4 h vs ≥2–2.5 h | n=31, 17 examined ST. 13 CS, 1 LS. Total N not reported. | Assoc. of ST with with HRQOL, consistent across television, computer and video screentime and across CSS and LS. 1 IS reported a dose-response relationship between screentime and HRQOL. HRQOL was lower across physical, mental and psychosocial health, school functioning, and general health domains. | Significant assoc. between higher screentime and lower HRQOL: >2–2.5 h/day ST associated with fall in HRQOL by 2.71 (1.59, 3.38; studies=2). |

+ or – used for direction of association of screentime (ST) with health outcomes. n refers to studies while N refers to total number of participants across the reviews. Per cent duplicate studies refers to the proportion of studies within a review that were included in any other included review.

assoc., associated with; Ad, adolescent; BMI, body mass index; C, child; CC, case-control study; CS, cross-sectional study; FV, fruit and vegetable; MA, meta-analysis; NoE, no evidence; RCT, randomised controlled trial; LS, longitudinal study; QOL, quality of life; ST, screentime; TST, total sleep time; TVST, television screentime; y, year.

Data extraction

Descriptive findings and results of any quantitative meta-analyses were extracted to a spreadsheet by NS and fully checked for accuracy by RV.

Evaluation of quality

The quality of systematic reviews including risk of bias was assessed using the adapted version of Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR).15 We characterised reviews as high, medium or low quality. High-quality reviews were required to have the following: provided a priori published designs (eg, published protocols or had ethics committee approval); searched at least two bibliographic databases plus conducted another mode of searching; searched for reports regardless of publication type; listed and described included studies; used at least two people for data extraction; documented the size and quality of included studies and used this to inform their syntheses; synthesised study findings narratively or statistically; assessed the likelihood of publication bias and included a conflict of interest statement. Medium-quality reviews were required to have: searched at least one database; listed and described included studies; documented the quality of the included studies and synthesised study findings narratively or statistically. Reviews did not meet these criteria were defined as low quality. Note we did not seek to assess the quality of primary studies included in each review.

Data synthesis and summary measures

Synthesis began by summarising review results and conclusions in note form. Reviews were then grouped by health domain: body composition (including adiposity); diet and energy intake; mental health and well-being; cardiovascular risk; fitness; cognition, development and educational attainments; sleep; pain and asthma. We assessed whether the conclusions of review-level evidence appeared reasonable, for example, considering effect sizes and designs. We noted meta-analyses undertaken in reviews separately to narrative findings. We noted dose-response findings where relevant. We made no attempt to quantitatively summarise findings across reviews as quantitative summaries should be undertaken at individual study level rather than at review level.

We then summarised findings across each domain according to the overall strength of evidence in terms of the consistency of findings across different reviews, the quality of the review, the design of included studies and how outcomes were assessed. In this we aimed to minimise so-called vote-counting, that is, not quantifying the number of studies reporting positive and negative findings regardless of their size and quality. Instead we weighed findings according to the size and quality of reviews (as assessed by AMSTAR) as well as the design of primary studies.16 In summarising findings across reviews, we defined strong evidence as consistent evidence of an association reported by multiple high-quality reviews, moderately strong evidence as consistent evidence across multiple medium-quality reviews, moderate evidence as largely consistent evidence across medium-quality reviews and weak evidence as representing some evidence from medium-quality reviews or more consistent evidence from poor-quality reviews.15

Patient involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the conceptualisation or carrying out of this research.

Results

Characteristics of the 13 included reviews are shown in table 1 with quality assessments for included reviews shown in table 2. The proportion of studies in each review that were also included in other reviews ranged from 0% to 22%. Table 3 shows the mapping of reviews to outcome areas by quality category. The objectives of many of the included reviews overlapped and many reviews considered multiple outcomes. There were six reviews which considered the associations of screentime with body composition measures (including obesity), three for diet and energy intake, seven for mental health related outcomes including self-esteem and quality of life, four for cardiovascular risk, four for fitness, three for sleep and one each for pain and asthma. The only high-quality review was limited to cardiovascular risk. We describe findings by domain below.

Table 2.

Quality assessment for included reviews

| Provides a priori design | Duplicate data extraction | Search ≥2 databases plus another mode of searching | Searched for reports regardless of their publication types | Included a list of included studies | Reports characteristics of individual studies | Assesses quality of studies | Uses the scientific quality of the studies appropriately | Uses appropriate methods to combine the findings of studies | Assessed likelihood of publication bias | Includes conflict of interest statement | Overall quality rating | |

| Pearson and Biddle19 | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | low |

| Hale and Guan24 | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | low |

| Marsh et al 1 | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | medium |

| Costigan et al 8 | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | medium |

| Dutch et al 9 | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | low |

| Goncalves de Oliveira et al 23 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | high |

| Hoare et al 20 | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | medium |

| Carson et al 17 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | medium |

| LeBlanc et al 18 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | medium |

| Tremblay et al 10 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | medium |

| van Ekris et al 11 | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | medium |

| Suchert et al 21 | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | medium |

| Wu et al 22 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | medium |

Table 3.

Mapping of reviews to subject area by quality

| High-quality reviews | Medium-quality reviews | Low-quality reviews | |

| Body composition including obesity | LeBlanc et al 18 | Duch et al 9 | |

| Costigan et al 8 | |||

| Tremblay et al 10 | |||

| van Ekris et al 11 | |||

| Carson et al 17 | |||

| Diet and energy intake | Costigan et al 8 | Pearson and Biddle19 | |

| Marsh et al 1 | |||

| Mental health outcomes including quality of life | LeBlanc et al 18 | ||

| Costigan et al 8 | |||

| Tremblay et al 10 | |||

| Suchert et al 21 | |||

| Carson et al 17 | |||

| Hoare et al 20 | |||

| Wu et al 22 | |||

| Cardiovascular risk | Goncalves de Oliveira et al 23 | Tremblay et al 10 | |

| van Ekris et al 11 | |||

| Carson et al 17 | |||

| Fitness | Costigan et al 8 | ||

| Tremblay et al 10 | |||

| van Ekris et al 11 | |||

| Carson et al 17 | |||

| Cognition, development and attainments | LeBlanc et al 18 | ||

| Tremblay et al 10 | |||

| Carson et al 17 | |||

| Sleep | Costigan et al 8 | Duch et al 9 | |

| Hale and Guan24 |

Body composition

Consistent evidence for an association between screentime and greater adiposity was reported in five medium-quality reviews and one low-quality review.

Overall screentime

In medium-quality reviews, Costigan et al 8 reported that 32/33 studies, including 7/8 studies with low risk of bias, identified a strong positive association of screentime with weight status; van Ekris et al 11 reported strong evidence for relationship between screentime and body mass index (BMI) or BMI z-score based on two high-quality studies and moderate evidence for relationship with overweight/obesity in three low-quality studies and Carson et al 17 reported a strong association between screentime and unfavourable body composition (obesity or higher BMI or fat mass) in 11/13 longitudinal studies, 4/4 case-control studies and 26/36 cross-sectional studies.

In a low-quality review, Duch et al 9 reported a positive association between screentime and BMI in 4/4 studies.

Television screentime

The great majority of findings related to television screentime. Tremblay et al 10 reported a moderate association between television screetime and adiposity measures, identified in 94/119 cross-sectional studies and 19/28 longitudinal studies. van Ekris et al reported strong evidence for a positive relationship between TV viewing time and incidence of overweight/obesity over time in three high-quality studies and in three low-quality studies. Carson et al reported that unfavourable adiposity was associated with television screentime in 14/16 longitudinal studies, 2/2 case-control studies and 58/71 cross-sectional studies. LeBlanc et al 18 reported that the association between television screentime and unfavourable adiposity measures could be seen at all ages, but that evidence quality was low for infants and moderate for toddlers and preschoolers.

Two reviews reported meta-analyses relating to television screentime. van Ekris et al reported that across 24 257 participants from 9 prospective cohorts, BMI at follow-up was not significantly associated with each additional hour of daily TV viewing (β=0.01, 95% CI −0.002 to 0.02), with high heterogeneity across studies. Adjustment for physical activity or diet did not materially change findings. In contrast, Tremblay et al reported that across four randomised controlled trials, decreased television screentime postintervention was associated with a pooled decrease in BMI of −0.89 kg/m2 (95% CI −1.467 to 0.11, p=0.01).

Computer, video, mobile or other screentime

Data on other forms of screentime were very sparse. In medium-quality reviews, Carson et al reported that unfavourable adiposity measures were associated with computer screentime in 3/4 studies but in 0/2 case-control studies and that findings in cross-sectional studies were highly inconsistent; Carson et al identified no evidence for an association between video/videogame screentime and adiposity and van Ekris et al identified no evidence for relationship between computer/computer game screentime with BMI or BMI z-score in 10 low-quality studies or with WC or WC z-score in 2 low-quality studies.

In the only meta-analysis, van Ekris et al reported that across 6971 participants from five prospective cohorts, BMI at follow-up was not significantly associated with each additional hour of daily computer screentime (β=0.00, 95% CI −0.004 to 0.01), with high heterogeneity across studies. Adjustment for physical activity or diet did not change findings materially.

Dose-response effects

A dose-response effect for television screentime was reported by two medium-quality reviews (Tremblay et al; LeBlanc et al) with a third (Carson et al) not distinguishing between television or other screentime. Carson et al reported that screentime dose-response was examined in 73 studies: higher screen time/TV viewing was significantly associated with unfavourable body composition with a 1-hour cut-point (8/11 studies), 1.5-hour cut-point (2/2 studies), 2-hour cut-point (24/34 studies), 3-hour cut-point (12/13 studies) or 4-hour cut-point (4/4 studies).

Summary

We conclude there is moderately strong evidence that higher television screentime is associated with greater adiposity, but that there is insufficient evidence for an association with overall screentime or non-television screentime. There is moderate evidence that a dose-response association is present for screentime or television screentime. However, there is no strong evidence for a particular threshold in hours of screentime.

Diet and energy intake

Associations of screentime with energy intake and/or diet factors were examined in two medium-quality and one low-quality review.

In a medium-quality review of experimental studies, Marsh et al 1 reported that there was strong evidence that i) screentime in the absence of food advertising was associated with increased dietary intake compared with non-screen behaviour; ii) television screentime increases intake of very palatable energy-dense foods and iii) there was weak evidence for video game screentime similarly increased dietary intake. They concluded there was moderate evidence that stimulatory effects of TV on intake were stronger in overweight or obese children than those of normal weight, suggesting the former are more susceptible to environmental cues.

In a medium-quality review, Costigan et al reported a negative association of screentime with healthy dietary behaviour in 3/5 studies. In a low-quality review, Pearson and Biddle19 reported moderate evidence that television screentime was positively associated with total energy intake and energy dense drinks and negatively associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in longitudinal studies in both children and adolescents. In cross-sectional studies, they identified moderate evidence for the same associations for television screentime in children and for overall screentime in adolescents.

Summary

We conclude there is moderate evidence for an association between screentime, particularly television screentime, and higher energy intake and less healthy diet quality including higher intake of energy and lower intake of healthy food groups.

Mental health and well-being

Associations between mental health and well-being and screentime were examined in seven medium-quality reviews.

Anxiety, depression and internalising problems

Only Hoare et al 20 reported on associations with anxiety, and found moderate evidence for a positive association between screentime duration and severity of anxiety symptoms.

Costigan et al reported a positive association of screentime with depressive symptoms in 3/3 studies. Similarly, Hoare et al reported strong evidence for a positive relationship between depressive symptomatology and screentime based on mixed cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Hoare et al also noted there was limited evidence for association between social media screentime and depressive symptoms. Suchert et al 21 reported a positive association of screentime with internalising problems (in 6/10 studies), but noted a lack of clear evidence for depressive and anxiety symptoms when measured separately.

In terms of dose-response for depressive symptoms, Hoare et al reported that higher depressive symptoms were associated with ≥2 hours of screentime daily in 3/3 studies. Suchert et al reported that three studies identified a curvilinear association between screentime and depressive symptoms, such that adolescents using screens in a moderate way showed the lowest prevalence of depressive symptoms.

Behaviour problems

Carson et al reported that an association between screentime and behavioural problems was examined in 24 studies. In longitudinal studies, a positive association with unfavourable behavioural measures was reported in 2/2 studies for total screentime and 3/5 studies for television screentime, but a null association was reported in 3/3 studies of video game screentime. In cross-sectional studies, positive associations were reported for television screentime (4/6 studies), computer use (3/5 studies) and video game screentime (3/4 studies). In contrast, Tremblay et al concluded there was poor evidence that television screentime was associated with greater levels of behaviour problems.

In terms of dose response, Carson et al reported that this was examined in two studies, which both reported that television screentime >1 hour daily was associated with unfavourable measures of behaviour.

Hyperactivity and inattention

Hyperactivity and attention were only considered in one review. Suchert et al reported that there was a positive association between screentime and hyperactivity/inattention problems in 10/11 studies.

Other mental health problems

LeBlanc et al reported that there was moderate evidence that television screentime was associated with poorer psychosocial health in young children aged 14 years.

Only one review each considered the association of screentime with eating disorders and suicidal ideation. Suchert et al reported there was no clear evidence for an association with eating disorder symptoms, while Hoare et al reported there was no clear evidence for a relationship with suicidal ideation.

Self-esteem

Effects on self-esteem were considered in three reviews. Hoare et al concluded there was moderate evidence for a relationship between low self-esteem and screentime. Carson et al reported that this association was not considered in longitudinal studies but that in cross-sectional studies, lower self-esteem was associated with screentime in 2/2 studies and with computer screentime in 3/5 studies, and no clear evidence for mobile-phone screentime.

In contrast, Suchert et al reported no clear evidence for an association with self-esteem and Tremblay et al similarly reported unclear evidence, with only 7/14 cross-sectional studies showing an inverse relationship between screentime and self-esteem.

Quality of life and well-being

Quality of life was considered in one review of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and in two reviews which reported on perceived quality of life or perceived health.

HRQOL as a formal measured construct was examined by Wu et al, 22 who reported consistent evidence that greater screentime was associated with lower measured HRQOL in 11/13 cross-sectional and 4/4 longitudinal studies. A meta-analysis of 2 studies found that ≥2–2.5 hours/day of screentime was associated with significantly lower HRQOL (pooled mean difference in HRQOL score 2.71 (95% CI 1.59 to 3.38) points) than those with <2–2.5 hours/day.

Suchert et al reported that there was a positive association between screentime and poorer psychological well-being or perceived quality of life in 11/15 studies. Costigan et al reported a negative association between screentime and perceived health in 4/4 studies.

Adjustment for physical activity

Suchert et al reported that 11 included studies examined the association between screentime and mental health adjusted for physical activity. They reported that in each study the association between screentime and poorer mental health (a range of outcomes) was robust to adjustment for physical activity, suggesting that screentime is a risk factor for poor mental health independently of displacement of physical activity.

Summary

There is moderately strong evidence for an association between screentime and depressive symptoms. This association is for overall screentime but there is very limited evidence from only one review for an association with social media screentime. There is moderate evidence for a dose-response effect, with weak evidence for a threshold of ≥2 hours daily screentime for the association with depressive symptoms.

There is moderate evidence for an association of screentime with lower HRQOL, with weak evidence for a threshold of ≥2 hours daily screentime.

There is weak evidence for association of screentime with behaviour problems, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, poorer self-esteem and poorer psychosocial health in young children. There is no clear evidence for an association with eating disorders or suicidal ideation. There is weak evidence that the association between screentime and mental health is independent of the displacement of physical activity.

Cardiovascular risk

Associations between screentime and cardiovascular risk were examined by one high-quality and three medium-quality reviews.

Metabolic syndrome/clusters of cardiovascular risk factors

In the only high-quality review, Goncalves de Oliveira et al 23 reported there was null evidence for the association of screentime or television screentime with the presence of the metabolic syndrome (MetS). In meta-analysis across six studies (n=3881), they did not identify a significant relationship, with the OR for >2 hours screentime=1.20 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.59), p=0.20; I2=37%). However, when weekend screentime was examined separately in two studies (n=1620), they found a significant association with presence of the MetS (OR=2.05 (95% CI 1.13 to 3.73), p=0.02; I2=0%). In a medium-quality review, Carson et al reported that an association between a clustered risk factor score and television screentime was reported in 2/2 longitudinal studies and 6/10 cross-sectional studies.

Individual cardiovascular risk factors

Three medium-quality reviews examined the evidence for an association between screentime various individual risk factors, for example, cholesterol, blood pressure, haemoglobin A1c or insulin insensitivity. Tremblay et al, van Ekris et al and Carson et al each reported there was no consistent evidence for an association with any risk factor, with evidence largely limited to single studies and not consistent across studies.

Summary

There is weak evidence of an association between screentime and television screentime with the MetS. There is no clear evidence for an association with any individual cardiovascular risk factor.

Fitness

Associations with fitness were examined by four medium-quality reviews. Two reviews, Costigan et al and Tremblay et al, noted that evidence for an association between screentime and fitness was weak and inconsistent. Indeed, Costigan et al noted that 2/5 studies reported a positive relationship, that is, that higher screentime was associated with higher physical activity.

In contrast, two reviews (Carson et al, and van Ekris et al) concluded there was strong evidence for an inverse association between screentime or television screentime and cardiorespiratory fitness. Carson et al noted that 4/4 studies examined a threshold and found that higher screentime was significantly associated with lower fitness when a 2 hour cut-point was used (4/4 studies).

Summary

There is weak and inconsistent evidence for an association between screentime or television screentime and cardiorespiratory fitness, with weak evidence for a 2-hour daily screentime threshold.

Cognition, development and attainments

Associations with CYP cognition and development were examined in three medium-quality reviews.

LeBlanc et al reported that there was low-quality evidence that television screentime had a negative impact on cognitive development in young children. Evidence was stronger among infants, where LeBlanc et al concluded that there was moderate-quality evidence that television screentime elicited no benefits and was harmful to cognitive development.

Tremblay et al reported there was poor evidence that greater television screentime was associated with poorer educational attainments. Carson et al also noted weak evidence that screentime or television screentime were associated with poorer attainments.

Summary

There is weak evidence that screentime particularly television screentime is associated with poorer educational attainments and has a negative effect on cognitive development in younger children.

Sleep

Associations with sleep were examined in one medium-quality and two low-quality reviews.

In a medium-quality review, Costigan et al reported a positive association between screentime and sleep problems in 2/2 studies. In low-quality reviews, Duch et al reported there was inconclusive evidence for an association between screentime and sleep duration. In contrast, Hale and Guan24 reported there was moderate evidence that overall screentime, television screentime, computer screentime, video screentime and mobile phone screentime were associated with poor sleep outcomes including delayed bedtimes, shortened total sleeptime, sleep-onset-latency and daytime tiredness. They estimated that there was approximately 5–10 min sleep bedtime delay with each additional hour of television screentime. Findings of significantly shorter total sleep time with greater mobile device screentime were reported in 10/12 studies, with 5/5 reporting greater subjective day-time tiredness or sleepiness.

Summary

There is weak evidence that screentime is associated with poor sleep outcomes including delay in sleep onset, reduced total sleep time and daytime tiredness. There is evidence from one review that this association is seen across all forms of screentime including television screentime, computer screentime, video screentime and mobile phone screentime.

Physical pain

Associations with pain were examined in one medium-quality review. Costigan et al reported that there was weak evidence for an association between screentime and neck/shoulder pain, headache and lower back pain, although this was examined in very few studies. As this was examined in only one review, we characterised the level of evidence as insufficient.

Asthma

Associations with asthma were examined in one medium-quality review. van Ekris et al reported there was insufficient evidence for a relationship between screentime or television screentime and asthma prevalence.

Discussion

This RoR summarises the published literature on the effects of screentime on CYP health and well-being. Evidence was strongest for adiposity and diet outcomes, with moderately strong evidence that higher television screentime was associated with greater obesity/adiposity and moderate evidence for an association between screentime, particularly television screentime, and higher energy intake and less healthy diet quality. Mental health and well-being were also the subject of a number of reviews. There was moderately strong evidence for an association between screentime and depressive symptoms, although evidence for social media screentime and depression was weak. Evidence that screentime was associated with poorer quality of life was moderate, however evidence for an association of screentime with other mental health outcomes was weak, including for behaviour problems, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, poorer self-esteem, poorer well-being and poorer psychosocial health in young children. Weak evidence suggested that mental health associations appeared to be independent of physical activity.

Evidence for other outcomes was notably less strong. There is weak evidence of an association between screentime (and television screentime) with the MetS, poorer cardiorespiratory fitness, poorer cognitive development and lower educational attainments and poor sleep outcomes. It is important to note that the weak evidence reported here largely relates to a lack of literature rather than weak associations. In contrast, there was no or insufficient evidence for an association of screentime with eating disorders or suicidal ideation, any individual cardiovascular risk factor, asthma prevalence or pain.

We identified no consistent evidence of benefits for health, well-being or development, although we acknowledge that screentime may be associated with benefits in other domains not assessed here.

Evidence for a dose-response relationship between screentime and health outcomes is generally weak. We found moderate evidence for a dose-response association for screentime or television screentime and adiposity outcomes, depression and HRQOL. However, we identified no strong evidence for a threshold in hours of screentime for adiposity and only weak evidence for a threshold of ≥2 hours daily screentime for the associations with depressive symptoms and with HRQOL. One review suggested there was a curvilinear relationship between screentime and depressive symptoms.21

Overall the quality of included reviews was moderate, with only one high-quality review and three low-quality reviews included. There were only four meta-analyses identified, two of television screentime and BMI and one each of screentime and the MetS and screentime and HRQOL. Almost all studies in each review were undertaken in high-income countries, the majority in each review undertaken in the USA. Overlap in included studies between reviews was generally low, suggesting that findings were not dominated by small numbers of individual studies.

A major weakness in the literature is its domination by television screentime, with smaller numbers of studies examining computer use or gaming and very few studies including mobile screen devices. None examined multiple concurrent screen use, although there is increasing evidence that CYP may combine screen-use such as using smartphones while watching television; young people report using multiple screens to facilitate filtering out of unwanted content, including advertisements.25 Thus, it is unclear to what extent these findings can be generalised to more modern forms of screen use including social media and mobile screen use. RoR are necessarily limited to including primary studies which have been included in systematic reviews and are thus necessarily limited in addressing very new developments. It may take some years before adequate research is available on modern digital screen use including social media and multiple screen use and their impacts on health.

A central issue in whether these findings are generalisable to other forms of screentime is the degree to which the effects of screentime relate to time spent on screen or content watched on screen or even the context in which the content is watched on screens. Screentime may act through use while sedentary (ie, displacing physical activity) or through more direct effects. These direct effects may be either through the content watched on screens (eg, desensitising children to violence or sexually explicit material; or exposure to bullying), through the displacement of socialisation or learning time (eg, leading to social isolation) or through more direct cognitive effects, for example, the impact of blue screen light on sleep patterns and impacts on attention and concentration.4 Our findings tell us little about the mechanisms by which screentime affects health, and it is plausible that the effects we identified on adiposity, fitness, cardiovascular risk, mental health and sleep are due to the sedentary effects of screen use. However, we did identify moderate evidence that screentime was associated with higher intake of energy dense foods, which unlikely to be mediated by sedentariness. Furthermore, there is weak evidence that associations of screentime with mental health outcomes are robust to adjustment for physical activity,21 suggesting that screentime may affect mental health independently of the displacement of physical activity.

We found no convincing evidence of health benefits from screentime. Yet some argue strongly that digital media have potential significant health, social and cognitive benefits and that harms are overstated. A prominent group of scientists recently argued that messages that screens are inherently harmful is simply not supported by solid research and evidence. Furthermore, the concept of screen time itself is simplistic and arguably meaningless, and the focus on the amount of screen use is unhelpful."12 They pointed out that research has focused on counting the quantity of screentime rather than investigating the contexts of screen use and content watched. Others have pointed out similar limitations in the literature on screen use and violence7 and that educational use of screens is promoted in many educational systems.13 Our review addressed quantity of screentime and did not investigate the impacts of contexts or content on health outcomes. However, findings of a curvilinear relationship between screentime and depressive symptoms in one of our reviews21 and the description of a similar relationship for adolescent well-being26 suggests that moderate use of digital technology might be important for social integration for adolescents in modern societies.

Limitations

Our review is subject to a number of limitations. Quality of included reviews was largely moderate or low, with only one high-quality review. Key factors for reviews not being classified as high quality were failing to assess the quality and likelihood of publication bias within included primary studies or failing specify an a priori design. The included reviews were not entirely independent, although the overlap in primary studies was low or very low for most, thus it is unlikely that our findings are biased by individual studies included in multiple reviews. Data were extracted by one researcher, and although data were checked carefully back to the publication by the second researcher, we did not use dual independent extraction. We did not attempt to contact the authors of articles we could not retrieve as this was a rapid review.

RoR are a methodology that is being developed and there is no agreed best practice; such reviews are only as good as the reviews included and the primary studies that are included within them.27 There were limitations regarding the reviews included in our study in terms of heterogeneity between reviews in definition of screentime exposures, definition of health outcomes and measurement tools, making comparisons difficult. Screentime was largely measured by self-report, although increasing numbers of studies over time used more objective measures of screentime. Reviews also largely failed to consider the processes by which screentime impacted on health outcomes. In our narrative synthesis of findings, we aimed to avoid vote-counting of numbers of positive or negative studies to judge strength of evidence. However, it is possible that our findings reflect methodological or conceptual biases in our included reviews. A limitation of reviews or reviews including our own is the necessary time lag for inclusion of primary studies in systematic reviews, meaning that they may not represent the most contemporary research. Data on mobile screen use were particularly limited in our included reviews. Aside from reviews focusing on very young children, data from the included studies did not allow us to comment separately on findings by age group.

Conclusions

There is considerable evidence that higher levels of screentime is associated with a variety of health harms for CYP, with evidence strongest for adiposity, unhealthy diet, depressive symptoms and quality of life. Evidence for impact on other health outcomes is largely weak or absent. We found no consistent evidence of health benefits from screentime. While evidence for a threshold to guide policy on CYP screentime exposure was very limited, there is weak evidence that small amounts of daily screen use is not harmful and may have some benefits.

These data broadly support policy action to limit screen use by CYP because of evidence of health harms across a broad range of domains of physical and mental health. We did not identify a threshold for safe screen use, although we note there was weak evidence for a threshold of 2 hours daily screentime for the associations with depressive symptoms and with HRQOL. We did not identify evidence supporting differential thresholds for younger children or adolescents.

Any potential limits on screentime must be considered in the light of a lack of understanding of the impact of the content or contexts of digital screen use. Given the rapid increase in screen use by CYP internationally over the past decade, particularly for new content areas such as social media, further research is urgently needed to understand the impact of the contexts and content of screen use on CYP health and well-being, particularly in relationship to mobile digital devices.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: RMV conceptualised the study, planned the methods, assisted with the extraction of data and analysis of findings led writing the paper. NS undertook the initial search and led the extraction of data and contributed to analysis of findings and writing the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data in this paper were obtained from published studies. No additional data are available from the authors.

References

- 1. Marsh S, Ni Mhurchu C, Maddison R. The non-advertising effects of screen-based sedentary activities on acute eating behaviours in children, adolescents, and young adults. A systematic review. Appetite 2013;71:259 73. 10.1016/j.appet.2013.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iannotti RJ, Janssen I, Haug E, et al. Interrelationships of adolescent physical activity, screen-based sedentary behaviour, and social and psychological health. Int J Public Health 2009;54 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):191 8. 10.1007/s00038-009-5410-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klesges RC, Shelton ML, Klesges LM. Effects of television on metabolic rate: potential implications for childhood obesity. Pediatrics 1993;91:281 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Domingues-Montanari S. Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. J Paediatr Child Health 2017;53:333 8. 10.1111/jpc.13462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reid Chassiakos YL, Radesky J, Christakis D, et al. Children and adolescents and digital media. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20162593 10.1542/peds.2016-2593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Canadian Paediatric Society DHTFOO. Screen time and young children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatr Child Health 2017;22:461 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferguson CJ, Beresin E. Social science’s curious war with pop culture and how it was lost: The media violence debate and the risks it holds for social science. Prev Med 2017;99:69 76. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Costigan SA, Barnett L, Plotnikoff RC, et al. The health indicators associated with screen-based sedentary behavior among adolescent girls: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:382 92. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duch H, Fisher EM, Ensari I, et al. Screen time use in children under 3 years old: a systematic review of correlates. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:102 10.1186/1479-5868-10-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:98 10.1186/1479-5868-8-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Ekris E, Altenburg TM, Singh AS, et al. An evidence-update on the prospective relationship between childhood sedentary behaviour and biomedical health indicators: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2016;17:833 49. 10.1111/obr.12426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Etchells P. on behalf of all signatories. Open letter: There is an important debate to be had about screen time, but we need quality research and evidence to support it. Guardian. London 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Straker L, Zabatiero J, Danby S, et al. Conflicting guidelines on young children’s screen time and use of digital technology create policy and practice dilemmas. J Pediatr 2018;202:300 3. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shackleton N, Jamal F, Viner R, et al. Systematic review of reviews of observational studies of school-level effects on sexual health, violence and substance use. Health Place 2016;39:168 76. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Caird J, Sutcliffe K, Kwan I, et al. Mediating policy-relevant evidence at speed: are systematic reviews of systematic reviews a useful approach? Evidence and Policy 2014. ISSN 1744-2648. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carson V, Hunter S, Kuzik N, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: an update. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2016;41:S240 S265. 10.1139/apnm-2015-0630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. LeBlanc AG, Spence JC, Carson V, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in the early years (aged 04 years). Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2012;37:753 72. 10.1139/h2012-063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pearson N, Biddle SJ. Sedentary behavior and dietary intake in children, adolescents, and adults. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:178 88. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoare E, Milton K, Foster C, et al. The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:108 10.1186/s12966-016-0432-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Suchert V, Hanewinkel R, Isensee B. Sedentary behavior and indicators of mental health in school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic review. Prev Med 2015;76:48 57. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu XY, Han LH, Zhang JH, et al. The influence of physical activity, sedentary behavior on health-related quality of life among the general population of children and adolescents: A systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187668 10.1371/journal.pone.0187668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goncalves de Oliveira R, Pinto Guedes D, Activity P, et al. Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Metabolic Syndrome in Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Evidence. PLos One 2016;11:1 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hale L, Guan S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic review Sleep Medicine reviews . 2015;21:50 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jago R, Sebire SJ, Gorely T, et al. "I’m on it 24/7 at the moment": a qualitative examination of multi-screen viewing behaviours among UK 10-11 year olds. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:85 10.1186/1479-5868-8-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Przybylski AK, Weinstein N. A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis. Psychol Sci 2017;28:204–15. 10.1177/0956797616678438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomson D, Russell K, Becker L, et al. The evolution of a new publication type: Steps and challenges of producing overviews of reviews. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:198 211. 10.1002/jrsm.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.