Spondyloarthritis (SpA) refers to a group of chronic inflammatory disorders that share common clinical, biological and pathophysiological characteristics. According to the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria, these inflammatory rheumatic diseases are subdivided into axial (Ax) SpA (including both radiographic (r) and non-radiographic (nr) forms) and peripheral SpA. Radiographic AxSpA (rAxSpA) corresponds to ankylosing spondylitis (AS), the prototypic and most common form of the disease. The clinical presentation of SpA is heterogeneous with musculoskeletal features (synovitis, sacroiliitis, spinal inflammation, enthesitis, dactylitis), but also extra-articular manifestations (psoriasis, anterior uveitis and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs)). One hallmark of the disease, and especially of AxSpA, is the presence of radiographic changes of the sacroiliac joints (SIJs), but also the development of progressive ossifications at entheseal sites.1 Although HLA-B27 has been identified as a major genetic marker of susceptibility to the disease, the pathophysiology of SpA still remains imperfectly understood. For roughly 15 years, TNF-α has been known as a leading inflammatory cytokine associated with joint inflammation in SpA. With the development of biological treatments, that is, TNF inhibitors (TNFi), the management of patients with SpA has considerably progressed. However, not all patients primarily respond to these treatments, indicating the involvement of other inflammatory mediators.

In fact, the IL-23/IL-17A axis has been identified as another major contributing pathway to inflammatory reaction in SpA.2 Indeed, genome-wide studies performed in patients with AS have identified polymorphisms in the IL-23 receptor (IL-23R) as a strong protective genetic factor.3 This polymorphism also provides protection against IBD and psoriasis through impairment of IL-17A production. The interaction of IL-23 (a heterodimeric cytokine with an IL-12/IL-23 p40 common subunit and a p19 IL-23 specific component) with its receptor leads to activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which in turn induces the expression of retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor-γt (RORγt), a major transcription factor for Th17 cells. Th17 cells are CD4+ T-helper cells that produce IL-17 family cytokines, mainly IL-17A and IL-17F, and other inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-22 and GM-CSF.4 Th17 cells are implicated in chronic inflammation and are considered to drive some autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis, multiple sclerosis (MS), but also SpA.5 Indeed, in certain but not all studies, circulating IL-17A has been found to be elevated in AS compared with healthy controls.6 The frequency of IL-17A-secreting cells was found to be higher in the spinal facet joints (a site of active inflammation in SpA) of patients with AS compared with samples from patients with osteoarthritis.7 Finally, in an experimental model of mouse arthritis, Sherlock et al identified a particular T-cell subset infiltrating the entheses.8 These cells exhibited a specific CD4–CD8–CD3+ phenotype, and expressed IL-23R and RORγt. They responded to IL-23 by producing TNF-α, IL-17A, and also IL-22 and CXCL1. In this model, overexpression of IL-23 by mini-circle technology led to severe inflammatory reaction with enthesitis, synovitis and joint destruction. Of interest, IL-17A was linked to joint inflammation, while IL-22 was linked to osteoproliferative changes.8 It should be noted that a similar cellular subset has not yet been identified in humans with SpA.9 However, group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) have been isolated in entheseal tissue obtained from individuals without inflammatory disease during spine surgery. These cells expressed RORγt, STAT3 and IL-23R and were able to produce IL-17A.10 Overall, this rationale has led to the development of treatments targeting IL-23 or IL-17A in SpA.2 Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the common IL-12/IL-23 p40 subunit, has proven to be effective in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, despite encouraging preliminary results in an open-label study, this biological agent is not effective in AS.11 Conversely, two monoclonal antibodies blocking the biological effects of IL-17A are available, namely secukinumab and ixekizumab. The results of phase III clinical trials with these agents confirm the rationale for targeting IL-17A in AS and SpA in general. Both are effective in psoriasis and PsA. Currently, only secukinumab is approved for the treatment of rAxSpA, that is, AS, but not in nrSpA.12 13

Conventional Th17 cells are CD4+ helper T cells that are a major source of IL-17A.4 However, other cellular subtypes may also produce this inflammatory cytokine, and most of them belong to the innate like-immune system.9 Indeed, other cellular sources of IL-17A have been identified. This includes γδ T cells, KIR3DL2+ and KLRG1+ T cells, ILC especially ILC3 cells, invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells, as well as mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells.9 14 The entheseal IL-23R+RORγt+CD4–CD8–CD3+ cells described in the animal model by Sherlock et al are also included in this cellular category.8 All these immune cell subsets, sensitive to IL-23, are collectively referred to under the term type 17 cells.

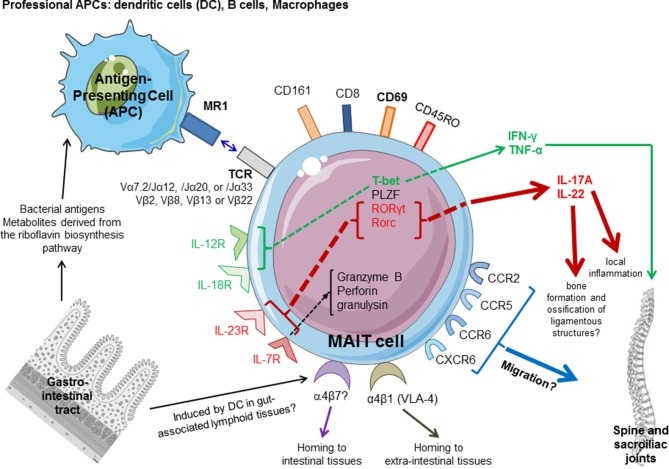

MAIT cells belong to the class of innate immune T cells and were first described in 1993 in human blood. The name stems from the abundance of these cells at mucosal and inner barriers, that is, the lamina propria of the gut and liver.15 16 This cellular subset is characterised by its dependence on a monomorphic MHC Class I–related protein called MR1 for its selection and activation. MAIT cells express a semi-invariant αβ TCR. The invariant α-chain is defined by the uniform use of Vα7.2 segment paired with Jα12, 20 or 33 (TCRAVIS2-AJ12, J20 or J33) which associates with a limited number of TCR β chains (figure 1). They are CD8+ or double negative (CD4–CD8–). The other phenotypic markers that characterise MAIT cells include high expression of CD161 (CD161high), expression of receptors for IL-7, IL-12, IL-18 and IL-23, as well as multiple chemokine receptors: CCR6, CXCR6 or CCR5. They also express α4β1, α4β7, CD28, the transcription factor RORγt and have an effector memory phenotype (CCR7–CD62L–CD45RO+). MAIT cells are restricted by MR1 molecule.17 Indeed, MAIT cells are activated by specific microbial non-peptide ligands presented by MR1. The bacterial antigens that may stimulate MAIT cells have been identified as vitamin B2 (riboflavin)–derived molecules. Thus, MAIT cells play a role as the first line of defense against pathogenic bacteria and yeasts, mainly at mucosal surfaces. On MR1 activation, MAIT cells produce inflammatory cytokines with a mixed Th1/Th17-like response. Indeed, MAIT cells have the capacity to produce IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-17A and IL-22.15 MAIT cells are primarily located at mucosal surfaces and in the blood, and they represent around 6% to 10% of circulating CD3+ T cells. Due to the expression of chemokine receptors, they can migrate to specific tissues, such as the lung, liver and gut. MAIT cells, as well other innate-like T cells, are at the interface between innate and adaptive immune responses. Their absence in germ-free animals and their role in bacterial defense argue for their involvement in mucosa.16 Mucosal immunity has been implicated as a contributing factor to the pathophysiology of several systemic immune-mediated diseases. Indeed, MAIT cells are located at the mucosal barrier; they play a role in bacterial defense and may modulate human microbiota; they have the capacity to migrate to the sites of active inflammation and to contribute to local damage. A substantial number of studies have reported the possible involvement of MAIT cells in sterile, non-bacterial inflammatory diseases, including MS, psoriasis, IBD, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and RA.18 A strong relationship between gut and joint inflammation is well described in SpA.19 In this way, more than 50% of patients with AS may have subclinical gut inflammation, as evidenced by microscopic signs of inflammation in the colon or ileum. Patients with SpA and chronic gut inflammation have a high degree of SIJ inflammation on MRI,9 and around 6.5% of patients with SpA will go on to develop clinical IBD during the course of their disease. Therefore, considering the gut–joint axis in SpA and the role of MAIT cells in mucosal immunity, these innate-like T cells are potential cellular players in SpA.

Figure 1.

Potential role of MAIT cells in spondyloarthritis (SpA). MAIT cells are activated by MR1 ligands derived from bacteria and yeasts able to produce vitamin B2 (riboflavin) metabolites. Cytokines, such as IL-7, IL-12, IL-18 and IFN-γ, can also directly activate MAIT cells by an antigen-independent mechanism. MAIT cells are characterised by the semi-invariant T-cell receptor (TCR) composed by an invariant α chain (Vα7.2 segment paired with Jα12, 20 or 33) and a restricted β chain repertoire (Vβ2, Vβ8, Vβ13 or Vβ22). They are CD8+ or double negative (CD4–/CD8–), express CD45RO isoform and high levels of CD161, several chemokine receptors (CCR2, CCR5, CCR6, CXCR6,…) and interleukin (IL) receptors, as well transcription factors, including some involved in IL-17A production (IL-23R, RORγt/RORc). MAIT cells are preferentially located at the inner barriers, such as the lamina propria of the intestine. The α4 integrins (α4β1 and α4β7) regulate tissue homing of activated lymphocytes. MAIT may express α4β7 as a marker suggesting activation in the gut. MAIT express also α4β1 integrin (also known as VLA-4), associated with chemokine receptors responsible for homing to the sites of active inflammation, presumably sacroiliac joints, entheseal structures and peripheral joints in SpA. Once activated by microbial ligands, they can produce high levels of Th17 cytokines, IL-17A and IL-22, and also Th1 cytokines (TNF, IFN-γ). IL-17A promotes local inflammation, while IL-22 contributes to osteoproliferative changes and ligamentous ossifications. Circulating MAIT of patients with SpA express CD69 activation marker. Factors implicated in the type 1 response are in green, while factors involved in the type 17 pathway are in red. PLZF, promyelocytic leukaemia zinc finger; RORγt, retinoid-related orphan receptor-γt.

Five studies have evaluated the frequency of circulating blood MAIT cells, as well as their functional capacity in SpA (table 1).20–24 One study also reported results from the synovial compartment.23 In all these studies, MAIT cells were identified as CD3+Vα7.2+CD161high cells. In two studies, the patient category that was primary evaluated was not patients with SpA, but rather patients with SLE or fibromyalgia syndrome, respectively, and SpA was used as a comparative group.20 21 In these latter studies, there was no difference in the proportion of MAIT cells between patients with SpA and the control group.20 21 In the study by Sugimoto et al, expression of CXCR4 on MAIT cells was identified as a marker to distinguish SpA from healthy controls (HC).21 Hayashi et al evaluated 30 patients with AS, among them 50% were receiving a biologic agent. There was a decreased proportion of circulating MAIT cells compared with HC. A correlation was observed between CD69 expression on MAIT cells and disease activity as evaluated by Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS).22 In these patients, the levels of IL-17A produced by MAIT cells after activation by phorbol-myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycine were higher compared with the levels obtained in HC. Finally, Gracey et al 23 evaluated a larger group of patients with AS, but 61% of them received a TNFi. According to previous results,22 they observed a low frequency of circulating MAIT cells in AS compared with HC.23 A subgroup of patients had joint effusion, allowing the assessment of the joint compartment. Indeed, MAIT cells were found in higher proportions in the synovial fluid compared with the circulation.23 In the blood, MAIT cells had the capacity to produce IL-17A since an elevated frequency of IL-17A+ MAIT cells was observed in AS. However, these results were restricted to the male population and were not observed in female patients with AS. Interestingly, the authors demonstrated that MAIT cells were primed by IL-7, a cytokine involved in T cell activation and homeostasis, but not IL-23. MAIT cells may produce IL-17A in response to IL-7.23 Our group also evaluated circulating MAIT cells in AS.24 Since MAIT cells may be influenced by different factors including drugs (see below), we chose to include in our study patients without a biological agent or corticosteroids. Indeed, all were treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The number of MAIT cells was decreased in the blood of patients with AS compared with HC. We also observed a decreased frequency of γδ T cells, as well as IFN-γ+CD4+ and IFN-γ+CD8+ (type 1) T cells. We also evaluated the functional capacity of MAIT cells to express intracellular cytokines (IL-17A, IL-22 and IFN-γ) after stimulation with PMA/ionomycine. Our results showed that patients with AS were characterised by a higher proportion of IL-17A+/IFN-γ+ MAIT cells and IL-22+ MAIT cells. These results were independent of gender. On the contrary, MAIT cells positive for IL-17A and negative for IFN-γ were only increased in female patients with AS. We did not observe a relationship between laboratory parameters of inflammation, disease activity scores (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index or ASDAS), and IL-22+ or IL-17A+ MAIT cells.24

Table 1.

Clinical studies evaluating MAIT cells in ankylosing spondylitis

| Author (year) (reference) |

Studied population AS (M/F) |

Treatments | Control population (M/F) | MAIT cell identification | Main results | Cytokine profile |

| Cho (2014)20 | 21 (19/2) | 0% under biologics or CTC | 54 SLE (3/51) 66 RA (12/54) 9 Behcet (7/2) 136 HC (69/67) |

CD3+Vα7.2+CD161high |

|

|

| Sugimoto (2015)21 | 37 SpA (6/31) (17 AS, 17 uSpA, 1 Psa,1 ReA) |

51% under biologics 48% under CTC |

26 FMS (1/25) 21 RA (2/19) 16 HC (2/14) |

CD3+Vα7.2+CD161high |

|

|

| Hayashi (2016)22 | 30 (28/2) | 50% under biologics 23% under NSAIDs 6% under CTC |

21 HC (20/1) | CD3+Vα7.2+CD161high |

|

Higher frequency of IL-17A+ MAIT in the blood of patients with AS compared with HC |

| Gracey (2016)23 | 54 (36/18) | 61% under biologics 58% under NSAIDs |

28 HC 16 RA |

CD3+Vα7.2+CD161high |

|

Higher frequency of IL-17A+ MAIT in the blood of male patients with AS compared with HC Lower frequency of IFNα+ MAIT in the blood of AS compared with HC Priming of MAIT cells by IL-7 |

| Toussirot (2018)24 | 36 (27/9) | 100% under NSAIDs 0% under biologics or CTC |

55 (32/23) | CD3+Vα7.2+CD161high |

|

Higher number of circulating IL-17A+IFNα+ MAIT and IL-22+ MAIT cells in patients with AS compared with HC |

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; CTC, corticosteroids; FMS, fibromyalgia syndrome; HC, healthy controls; M/F, male/female; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ReA, reactive arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; uSpA, undifferentiated spondyloarthritis.

Overall, these results show that MAIT cells are deregulated in AS and circulate at a low frequency compared with normal subjects. Similar results have been reported in other immune-mediated diseases such as RA, MS, SLE, IBD and psoriasis.18 MAIT cells have the capacity to migrate to the site of inflammation due to their chemokine receptor expression.16 As previously reported in RA, MAIT cells in AS are found to be increased in the synovial fluid compared with the blood in patients with peripheral arthritis.25 Whether MAIT cells are also located at the entheses as well as in the SIJ is currently unknown and it is a major limitation of the discussed studies, including ours.24 In fact, such axial skeletal structures are of limited accessibility. In addition, the reduced frequency of MAIT cells in the circulation does not result from apoptosis. This hypothesis was examined in one study, and MAIT cells from patients with AS have comparable caspase-3 and Fas expression as compared with HC.22

The frequency of MAIT cells was not always reduced in the different studies.20 21 This may be related to the patient demographics, but also the treatments they received. The gating strategy that was used in the different studies to analysed MAIT cells by flow cytometry may also explain the heterogeneity of these results. Indeed, several factors may influence MAIT cell frequency and function: they decrease with age, are higher in obese subjects and are reduced with smoking habits.15–17 Conversely, gender does not affect MAIT cells.15 In addition, some drugs or their metabolites may be presented by MR1, and thus may influence MAIT cell function. These include corticosteroids, methotrexate and also NSAIDs (diclofenac).26 The influence of biological agents (TNFi and anti-IL17A agents) on MAIT cells is currently unknown, but it is conceivable that they may modulate their functional capacity. Therefore, this may have biased some results.22 23 Alternatively, assessing drug-free patients is challenging and they are difficult to select in clinical practice.

MAIT cells in patients with AS have the capacity to produce IL-17A, but also IFN-γ and IL-22. According to the different studies performed in AS, MAIT cells are characterised by a Th17 or Th1/Th17-like phenotype. MAIT cells express RORγt, a transcription factor associated with IL-17A-producing subset.15 16 In a mouse model of arthritis, it was demonstrated that MAIT cells became activated on IL-23 stimulation and had arthritogenic potency, suggesting their role in joint inflammation.27 Taken together, these results highlight the potential role of MAIT cells in AS and their capacity to produce IL-17A and contribute to a Th17-like immune response. This also indicates that the source of IL-17A in SpA is not restricted to conventional CD4+ Th17 cells and involves innate-like T cells.9

Our results showed the enhanced expression of IL-22 by MAIT cells in AS.24 The role of IL-22 in arthritis has been suggested in a collagen-induced arthritis model, in which IL-22-deficient mice exhibited decreased incidence of arthritis.28 In addition, it has been suggested that IL-22 may promote osteoclastogenesis in RA.29 In SKG mice that developed SpA-like disease after microbial antigen injection, IL-22 together with IL-17A has been shown to promote enthesitis.30 In parallel, in the mouse model of arthritis described by Sherlock et al, overexpression of IL-23 induced the production of IL-22 by entheseal IL-23R+CD4‒CD8‒CD3+ T cells, and IL-22 was associated with the induction of genes implicated in the regulation of bone formation, thus promoting ligamentous ossification.8 IL-22, together with IFN-γ and TNF-α, also has the capacity to influence the proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal stroma cell (MSC) towards an osteogenic phenotype. IL-22 alone can promote the expression of osteogenic transcription factors, indicating that these effects on MSC may represent a pathway for new bone formation in AS.31 Together with our results,24 this supports the hypothesis that IL-22+ MAIT could contribute to bone formation and ossification of ligamentous structures in SpA.

MAIT cells are found at mucosal sites, including the lamina propria of the gut. In IBD, MAIT cells accumulate in the inflamed mucosa of the patients.18 MAIT cells may express α4β7, an integrin for homing to the intestinal barrier.15 16 Similar to AS, IL-17A production by MAIT cells is enhanced in patients with IBD. MAIT cells may also produce IL-17A in the skin of patients with psoriasis.18 Overall, these data indicate that, in SpA-associated diseases (IBD and psoriasis), MAIT cells are involved in the local inflammatory response. Due to their location, their involvement in bacterial defense, their activation by bacterial riboflavin-derived metabolite antigens and their functional capacity, MAIT cells together with other innate-like T cells may thus contribute to the joint–gut axis that is well described in SpA.32

However, some unanswered questions remain. The specific expression of chemokines (CCR2, CCR6, CCR9) and α4β1 and α4β7 integrins by MAIT cells has not been determined in AS. This will contribute to a better understanding of the specific homing process to the gut and/or joint of these cells. It will certainly confirm that MAIT cells mainly originate from the gut. Only patients with a radiographic form of the disease (ie, AS) have been evaluated, and results are lacking for the nrAx SpA group. As stated above, the specific effect of biological agents on MAIT cells deserves additional investigation. In fact, it is relevant to examine whether TNFi modulate cytokine production by MAIT cells. Since IL-22 is involved in the regulation of bone ossification,29 31 the relationship between IL-22+ MAIT cells and SpA radiographic damage (by means of the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score) is also a relevant question. Finally, innate-like T cells are not restricted to MAIT cells and include other cellular subsets that have the capacity to produce IL-17A and other cytokines implicated in SpA pathophysiology. For instance, ILC3 cells producing IL-17A and IL-22 are observed in the gut, the circulation and the synovial fluid of patients with SpA.33 They are also observed in entheseal structures.10 IL-17A+γδ T cells are expanded in the peripheral circulation of patients with active AS.34 In a mouse model of SpA that overexpressed IL-23, γδ T cells accumulated in the entheses, but also the aortic root and the ciliary body.35 The relative contribution of the different innate-like T cells to the Th17 axis in SpA thus warrants further exploration. Finally, one major question is the specific expression of MAIT cells in the entheses of patients with SpA.

Despite these remarks, accumulating data indicate that MAIT cells are involved in AS and SpA in general, contributing to IL-17A production in the circulation, and thus to the IL-17 pathway of SpA. Currently, it is considered that IL-17A production by MAIT cells is 10-fold higher than by conventional Th17 cells.36 MAIT cells are also a source of IL-22 that may participate in the specific pathogenic process of ligamentous ossification of SpA. MAIT cells are deregulated in number, function and location in AS, strengthening the importance of innate and innate-like sources of IL17A and IL-22. All these recent findings pave the way to reconsidering the IL-17 axis in SpA and to examining the contribution of the different innate-like T cells to the inflammatory response in SpA. Whether MAIT cells and/or other innate-like T cells may be a target for future therapeutic intervention (by the use of MR1 ligands) requires additional data on the role of these cells in SpA pathophysiology.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have agreed to the contents of the manuscript in its submitted form to RMD Open. Each individual named as an author meets the journal’s criteria for authorship.

Funding: This work was supported by recurrent grants from the INSERM U1098 and INSERM CIC-1431, EFS BFC and University of Burgundy Franche-Comté, as well as the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (LabEX LipSTIC, ANR-11-LABX-0021) and Région Bourgogne Franche-Comté (support to LipSTIC 2017).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Taurog JD, Chhabra A, Colbert RA. Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2016;374:2563–74. 10.1056/NEJMra1406182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yeremenko N, Paramarta JE, Baeten D. The interleukin-23/interleukin-17 immune axis as a promising new target in the treatment of spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014;26:361–70. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Di Meglio P, Di Cesare A, Laggner U, et al. . The IL23R R381Q gene variant protects against immune-mediated diseases by impairing IL-23-induced Th17 effector response in humans. PLoS One 2010;6:e17160 10.1371/journal.pone.0017160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miossec P. Update on interleukin-17: a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthritis and implication for clinical practice. RMD Open 2017;3:e000284 10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Toussirot E. The IL23/Th17 pathway as a therapeutic target in chronic inflammatory diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2012;11:159–68. 10.2174/187152812800392805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jandus C, Bioley G, Rivals JP, et al. . Increased numbers of circulating polyfunctional Th17 memory cells in patients with seronegative spondylarthritides. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2307–17. 10.1002/art.23655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Appel H, Maier R, Wu P, et al. . Analysis of IL-17(+) cells in facet joints of patients with spondyloarthritis suggests that the innate immune pathway might be of greater relevance than the Th17-mediated adaptive immune response. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R95 10.1186/ar3370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sherlock JP, Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, et al. . IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-γt+CD3+CD4−CD8− entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med 2012;18:1069–76. 10.1038/nm.2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Venken K, Elewaut D. New immune cells in spondyloarthritis: key players or innocent bystanders? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015;29:706–14. 10.1016/j.berh.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cuthbert RJ, Fragkakis EM, Dunsmuir R, et al. . Brief report: group 3 innate lymphoid cells in human enthesis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1816–22. 10.1002/art.40150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poddubnyy D, Hermann KG, Callhoff J, et al. . Ustekinumab for the treatment of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results of a 28-week, prospective, open-label, proof-of-concept study (TOPAS). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:817–23. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. . Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sieper J, Deodhar A, Marzo-Ortega H, et al. . Secukinumab efficacy in anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced subjects with active ankylosing spondylitis: results from the MEASURE 2 Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:571–92. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Venken K, Elewaut D. IL-23 responsive innate-like T cells in spondyloarthritis: the less frequent they are, the more vital they appear. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2015;17:30 10.1007/s11926-015-0507-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dias J, Boulouis C, Sobkowiak MJ, et al. . Factors influencing functional heterogeneity in human mucosa-associated invariant T cells. Front Immunol 2018;9:1602 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kumar V, Ahmad A. Role of MAIT cells in the immunopathogenesis of inflammatory diseases: new players in old game. Int Rev Immunol 2018;37:90–110. 10.1080/08830185.2017.1380199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keller AN, Corbett AJ, Wubben JM, et al. . MAIT cells and MR1-antigen recognition. Curr Opin Immunol 2017;46:66–74. 10.1016/j.coi.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chiba A, Murayama G, Miyake S. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol 2018;9:1333 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. De Wilde K, Debusschere K, Beeckman S, et al. . Integrating the pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis: gut and joint united? Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015;27:189–96. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cho YN, Kee SJ, Kim TJ, et al. . Mucosal-associated invariant T cell deficiency in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2014;193:3891–901. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sugimoto C, Konno T, Wakao R, et al. . Mucosal-associated invariant T cell is a potential marker to distinguish fibromyalgia syndrome from arthritis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121124 10.1371/journal.pone.0121124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayashi E, Chiba A, Tada K, et al. . Involvement of mucosal-associated invariant T cells in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1695–703. 10.3899/jrheum.151133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gracey E, Qaiyum Z, Almaghlouth I, et al. . IL-7 primes IL-17 in mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, which contribute to the Th17-axis in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:2124–32. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Toussirot É, Laheurte C, Gaugler B, et al. . Increased IL-22- and IL-17A-producing mucosal-associated invariant T cells in the peripheral blood of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Front Immunol 2018;9:1610 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim M, Yoo SJ, Kang SW, et al. . TNFα and IL-1β in the synovial fluid facilitate mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cell migration. Cytokine 2017;99:91–8. 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Keller AN, Eckle SB, Xu W, et al. . Drugs and drug-like molecules can modulate the function of mucosal-associated invariant T cells. Nat Immunol 2017;18:402–11. 10.1038/ni.3679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chiba A, Tajima R, Tomi C, et al. . Mucosal-associated invariant T cells promote inflammation and exacerbate disease in murine models of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:153–61. 10.1002/art.33314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Geboes L, Dumoutier L, Kelchtermans H, et al. . Proinflammatory role of the Th17 cytokine interleukin-22 in collagen-induced arthritis in C57BL/6 mice. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:390–5. 10.1002/art.24220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang X, Zheng SG. Interleukin-22: a likely target for treatment of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:615–20. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Benham H, Rehaume LM, Hasnain SZ, et al. . Interleukin-23 mediates the intestinal response to microbial β-1,3-glucan and the development of spondyloarthritis pathology in SKG mice. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:1755–67. 10.1002/art.38638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. El-Zayadi AA, Jones EA, Churchman SM, et al. . Interleukin-22 drives the proliferation, migration and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells: a novel cytokine that could contribute to new bone formation in spondyloarthropathies. Rheumatology 2017;56:488–93. 10.1093/rheumatology/kew384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Debusschere K, Lories RJ, Elewaut D. MAIT cells: not just another brick in the wall. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:2057–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ciccia F, Guggino G, Rizzo A, et al. . Type 3 innate lymphoid cells producing IL-17 and IL-22 are expanded in the gut, in the peripheral blood, synovial fluid and bone marrow of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1739–47. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kenna TJ, Davidson SI, Duan R, et al. . Enrichment of circulating interleukin-17-secreting interleukin-23 receptor-positive γ/δ T cells in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1420–9. 10.1002/art.33507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reinhardt A, Yevsa T, Worbs T, et al. . Interleukin-23-dependent γ/δ T cells produce interleukin-17 and accumulate in the enthesis, aortic valve, and ciliary body in mice. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2476–86. 10.1002/art.39732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rahimpour A, Koay HF, Enders A, et al. . Identification of phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous mouse mucosal-associated invariant T cells using MR1 tetramers. J Exp Med 2015;212:1095–108. 10.1084/jem.20142110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]