Abstract

Hydrogels are promising scaffolds for adipose tissue regeneration. Currently, the incorporation of bioactive molecules in hydrogel system is used, which can increase the cell proliferation rate or improve adipogenic differentiation performance of stromal stem cells but often suffers from high expense or cytotoxicity because of light/thermal curing used for polymerization. In this study, decellularized adipose tissue is incorporated, at varying concentrations, with a thiol-acrylate fraction that is then polymerized to produce hydrogels via a Michael addition reaction. The results reveal that the major component of isolated adipose-derived extra-cellular matrix (ECM) is Collagen I. Mechanical properties of ECM polyethylene glycol (PEG) are not negatively affected by the incorporation of ECM. Additionally, human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs) are encapsulated in ECM PEG hydrogel with ECM concentrations varying from 0% to 1%. The results indicate that hASCs maintained the highest viability and proliferation rate in 1% ECM PEG hydrogel with most lipids formation when cultured in adipogenic conditions. Furthermore, more adipose regeneration is observed in 1% ECM group with in vivo study by Day 14 compared to other ECM PEG hydrogels with lower ECM content. Taken together, these findings suggest the ECM PEG hydrogel is a promising substitute for adipose tissue regeneration applications.

Keywords: adipogenesis, adipose, extracellular matrix, hydrogel, regeneration

1. Introduction

Every day, thousands of surgical procedures are performed to replace or repair damaged or injured tissue.[1] Evolving out of a need to address concerns pertaining to tissue transplantation, including the limited availability of healthy tissue, the field of tissue engineering seeks to facilitate the generation of viable tissue through the combination of cells and a cellular scaffold.[1,2] Adipose tissue engineering is a promising alternative for common techniques which involve in autologous fat tissue transfer, fat grafting techniques, and usage of commercial materials like silicones. These traditional techniques exhibit many limitations like donor site morbidity, graft degradation over time, and multiple sessions of surgical procedures.[3] Hydrogels are considered to be a powerful synthetic analogue of extra-cellular matrix (ECM) applied in adipose tissue engineering, owing to its structure similar to that of the native ECM, bioactive functionalities, and porous 3D architecture within any size or shape of defects prior to gelation.[4]

A common strategy is to seed 3D scaffolds with regenerative cell populations, such as adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs), to create tissue substitutes used for inducing stable and predictable adipose formation.[5] However, this therapy should be considered in correlation with the extensive cell expansion, immune rejection, limited cell survival and retention after treatment, and difficulties of controlling cell fate.[6] One of the promising approaches to overcome these limitations is to use cell-free systems based on tissue-specific scaffolds, which can actively participate in the recruitment of the body’s endogenous cells for tissue regeneration.[7]

Bioactive molecular encapsulation in cell-free hydrogel systems can serve as an alternative to 3D porous scaffolds that could be transplanted to recipient to guide repair and return of function of tissue or organs.[8] However, bioactive molecules for delivery, such as basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor are expensive and lack stability in physiological environments.[9] Comparatively, natural bioscaffolds, derived from ECM, offer advantages in availability and include the provision of a tissue-specific microenvironment that can be remodeled by host cells and integrate with the surrounding tissues.[10] Naturally derived scaffolds and hydrogel have been used for many years and have demonstrated potential to support cell growth while maintaining their volume. Recent efforts have extended this research to adipose-derived ECM and its ability to support the differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs).[11]

Biomaterials derived from decellularized adipose tissue (DAT) have been developed including 3D scaffolds, microcarriers, and foams,[10,12] which provide a highly conducive milieu for adipose tissue formation both in vitro and in vivo.[5,13] Moreover, it can naturally induce adipogenic differentiation of hASCs in culture without the supplementation of adipogenic medium.[14] However, these delivery systems are fabricated via either photopolymerization or theromopolymerization. The application of light or thermal curing might limit the application as an injectable graft in the clinic.

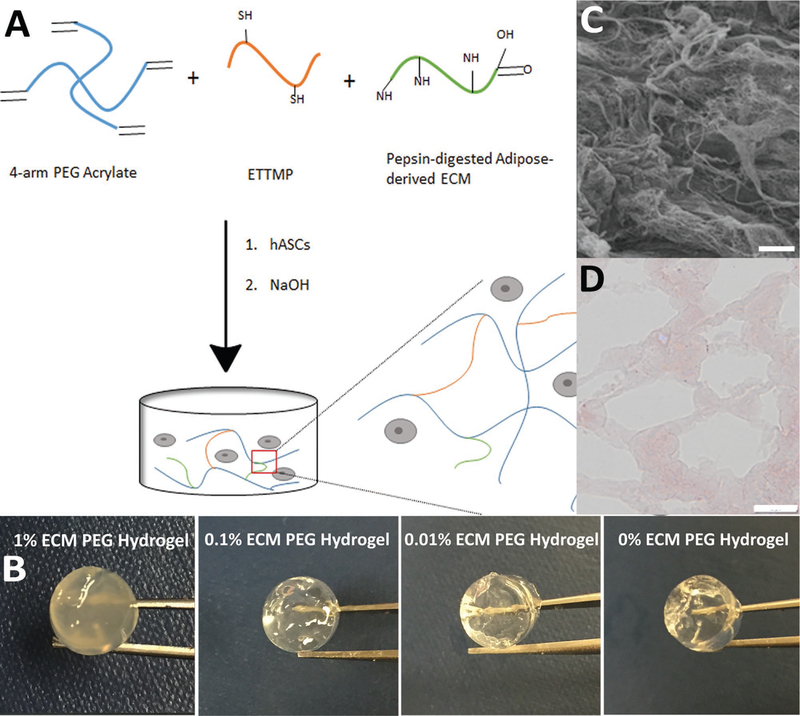

Based on the various reported studies of the above mentioned scaffolds, we hypothesized that polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogel, incorporated with adipose-derived ECM, fabricated via thiol-ene platform and Michael addition reaction (Figure 1A,B) could be a biocompatible hydrogel system and would support stem cell growth and adipose differentiation, which could be potentially applied for fat tissue regeneration.

Figure 1.

Extraction of adipose-derived ECM and fabrication of ECM PEG hydrogel: A) Schematic illustration of ECM PEG hydrogel via a Michael addition reaction. B) Representative photographs of hydrogel with different ECM concentrations. Macroscopically, the color and transparency of hydrogel differ among groups, especially the 1% ECM PEG hydrogel group. C) Porous structures of ECM under scanning electrical microscope. Scale bar: 10 µm. D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of ECM PEG hydrogel, which shows the porous network under microscope. Scale bar: 50 µm.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Four arm PEG-Acrylate (MW 10000, 5 g) was purchased from Laysan Bio Inc. (AL, USA). Dialysis sacks (MWCO 3500) were obtained from Fisher Scientific (PA, USA). Ethoxylated trimethylolpropane tri-3-mercaptopropionate (ETTMP, Thiocure 1300) was from Bruno Bock (Marschacht, Germany). Pierce BCA Assay Kit, Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit, LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/ F12 (DMEM-F12), fetal bovine serum (FBS), Rat Tail Collagen I Hydrogel, Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, DyLight 650 anti-perilipin-2/ADFP polyclonal rabbit primary antibody were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (PA, USA). Other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (PA, USA). All chemicals were reagent grade and used as received.

2.2. Adipose Tissue Procurement and Processing

Adipose tissue was obtained from elective cosmetic surgery procedures performed at Hershey Medical Center, Pennsylvania State University. Informed signed consents were obtained from all the patients. Hundred grams was first placed in 200 mL of 3.4 m sodium chloride (NaCl) buffer for 1 h. The tissue was then homogenized in solution. Fibrous tissue that could not be mechanically homogenized was continuously removed and collected, while all other tissue components were discarded as waste. Hundred milliliters of 2 m urea buffer was added to the collected fibrous tissue, and the solution was refrigerated for 48 h. The fibrous tissue solution was then centrifuged three times at 23 000 × g, 4 ˚C for 20 min. After each centrifugation, the pelleted tissue was collected and the solvent was discarded as waste. The fibrous pellet was then dialyzed against deionized water for 24 h before being digested with 0.5% w/v pepsin in 0.5 m acetic acid. Upon completion of the digestion reaction, the pepsin was deactivated by raising the pH of the solution to 9.0 using 1 m sodium hydroxide (NaOH). After overnight incubation at 37 ˚C, the pH of the solution was lowered to 7.4 with 1 m hydrochloric acid (HCl). The solution was dialyzed against deionized water for 24 h before being lyophilized, yielding a DAT ECM powder substance. The ECM powder was gas sterilized by ethylene oxide prior to use in vitro studies. Total protein contents were quantified using Pierce BCA Assay.

2.3. Total Protein Extraction in ECM for Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

Fifteen microliters of digestion buffer (8 mg mL−1 ammonium bicarbonate in water), 3 µL reducing reagent (30 mg mL−1 TCEP), and up to 12 µL sample solution containing 7 µg lyophilized ECM powder or 12 µg bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard protein (total volume 30 µL) was combined and mixed thoroughly. The mixture was then reduced at 50 ˚C TCEP for 7 min, cooled to room temperature, and spanned down to collect the sample. Three microliters of alkylating reagent (18 mg mL−1 iodoacetamide in digestion buffer) was added to the sample and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 min. Three microliters of proteomics grade trypsin activated with digestion buffer (0.1 µg µL−1) was added and incubated at 37 ˚C for 3 h and stored at ‒20 ˚C.

Protein identity was established by proteomics analysis. A LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) with a Dionex Ultimate 3000 nano-LC system was used to analyze tryptic peptides. The resulting LC-MS2 data was processed by Proteome Discoverer 1.3 application (Thermo Scientific, USA) and searched against a Human Protein Sequence Database (Uniprot, UP000005640, 70 939 entries) to which the common contaminating protein sequences were appended.

2.4. Fabrication of ECM PEG Hydrogel

ECM PEG hydrogels were prepared according to the protocol previously published.[15] Hydrogel reagents were reacted together using Michael addition (Figure 1A). Adipose extracellular matrix proteins in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were preincubated for 30 min with PEG-acrylate. ECM additives beyond 1% w/v% of total volume did not disperse homogeneously, leading to an unstable hydrogel. During preincubation, a solution of ETTMP, and 1 m NaOH was made. After the initial reaction of ECM proteins with PEG-acrylate in PBS, the solution containing PEG-acrylate and ECM was then mixed with the solution containing ETTMP and NaOH, resulting in polymerization. Thirteen milligrams of PEG, 2.03 µL ETTMP, 1.35 µL NaOH, and ECM at various concentrations (0%, 0.01%, 0.1%, and 1%) were added in a 135 µL hydrogel system. For cell encapsulation study, hASCs were mixed with PEG-ECM-PBS solution first and encapsulated in hydrogel after adding ETTMP-NaOH solution.

2.5. Physiochemical Characterizations of ECM PEG Hydrogel

2.5.1. Distribution of ECM in the Hydrogel via Masson’s Trichrome Staining

The hydrogels were embedded for cryosection and stained with Masson’s Trichrome Staining Kit using the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the cryosection was stained in working Weigert’s iron hematoxylin solution for 30 s, and washed in deionized water for 5 min. It was then put in Biebrich scarlet–acid fuchsin for 5 min. After being rinsed in water, the slides were placed in phosphomolybdic/phosphotungstic acid solution for 10 min and then in Aniline blue solution for 7 min. Rinsed briefly in deionized water, the sections were placed in 1% acetic acid solution for 30 s. After that, they were dehydrated and mounted. Images were taken (BX51, Olympus, USA) and collagen distribution was measured and analyzed via color counting software (Photoshop CS3, Adobe, USA). Each sample was randomly measured in five different positions and four total samples were included for analysis (n = 20).

2.5.2. Compressive Strength

The compressive strength of the hydrogels was tested using a dynamic mechanical analyzer (RSA-G2, TA, USA). The hydrogel was compressed with 250 n load cell at a cross-head speed of 0.05 mm s−1 until it reaches 70% strain. The stress– strain curves were plotted and Young’s modulus was calculated based on the curve.

2.5.3. Swelling Study

Hydrogel samples were soaked in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37 ˚C for 4 days to get the equilibrium swollen mass (Ms). To obtain the dry polymer mass (Md), samples were rinsed with deionized water to remove PBS salt, frozen, and lyophilized overnight.[16] The swelling ratio (Ms/Md) was calculated.

2.5.4. Degradation Study

The in vitro degradability was tested in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37 ˚C. A lyophilized hydrogel samples (n = 3) were accurately weighed and then immersed in 10 mL of PBS (with 1% penicillin/ streptomycin) for different time points up to 28 days, with the medium changed every week. Samples were taken out at each time point, rinsed with deionized water, then frozen, and lyophilized. The percentage of degradation was calculated from the dry mass of the sample before and after the immersion, and normalized to the dry mass of the sample before immersion.

2.5.5. Confocal Microscope and MATLAB Study on Pore Size and Porosity

The porosity and pore size of the hydrogel containing the fluorescently labeled particles was assessed using MATLAB (Math-Works, USA) analysis.[17] First, gels were incubated with high molecular weight fluorescein-labeled dextran (500 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Next, images were collected by a scanning confocal microscope (FV10i, Olympus, USA) using a 10× objective and z-stacks were taken every 10 µm over 400 µm. The images were analyzed using a custom MATLAB code to quantify the pore size, as well as the overall porosity of hydrogel.

2.5.6. FTIR Analysis

Hydrogel samples were put in the incubator overnight and lyophilized for 24 h. VERTEX 70v FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Billerica, MA) was used to measure acrylate and thiol constituents in ETTMP, PEG, and lyophilized gels (characterized by S—H stretch at 2550–2600 cm−1 and C=C stretch at 1675–1600 cm−1).

2.6. In Vitro Study

2.6.1. Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Culture

The fat tissues were minced with scissors in the collagenase solution consisted of Hanks’ balanced salt solution, BSA (fatty acid-free, pH 7.0, 3.5 g per 100 mL Hanks’), and 1% type II collagenase (3.0 mg g−1 of fat). The centrifuge tubes were shaken at 100 rpm for 50 min at 37 ˚C, and a three-layer suspension was obtained. The fatty layer and most of the supernatant was discarded, leaving the pellet at the bottom. The pellet in each tube was then suspended in 10 mL of erythrocyte lysis buffer (pH = 7.4), vortexed, and centrifuged again at 1000 rpm for 10 min at 37 ˚C. The pellets were suspended in the plating medium consisted of DMEM/F12 with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Adherent ASCs were expanded for a period of 5–8 days at 37 ˚C and the medium was changed every other day until the cells achieved 80% confluence.

2.6.2. Cell Encapsulation

hASCs were used in the evaluation of scaffolds of different ECM compositions; 2 mg mL−1 Collagen I hydrogel was used as a positive control and PEG hydrogel with no ECM was used as a negative control. hASCs were encapsulated in the scaffolds at 1 × 105 cells mL−1. Hydrogels were formed in a 96-well plate at a volume of 45 µL and were polymerized at 37 ˚C to ensure cell suspension and survivability. Encapsulated cells were cultured in either stromal medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic solution) or induction medium (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic solution, 10 µg mL−1 insulin, 1 µm dexamethasone, 200 µm indomethacin, 0.5 mm 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine), for up to 28 days with media maintenance performed three times a week.

2.6.3. Assessment of Cell Viability and Proliferation

After hASCs had been cultured with stromal medium for 1, 14, 21, 28 days, live and dead cells were stained with a Live/Dead Staining Kit containing fluorescein diacetate/ethidium bromide (EB), and nuclei were stained with 4ˊ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), visualized with a fluorescent microscopic imaging system (IX73, Olympus, USA). Cell number was manually counted with DAPI positive cells using ImageJ (NIH, USA).

2.6.4. Cell Morphology via Cryo-Scanning Electron Microscopy

Hydrogel samples were placed on the sample holder with cyro matrix and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were then transferred to the pre-chamber and the surface was fractured. After the sample surface was coated using Pt sputter, the sample was moved to the microscope’s cyro stage. The sample was imaged using Sigma-VP-FESEM at different magnifications with InLens SE or LnLens Duo Detector (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) at 10 kV voltage and a working distance of 8.5 mm.

2.6.5. Evaluation of Adipogenic Differentiation via Oil Red O Staining and Quantification

Adipogenic inducing components were added for hASCs encapsulated within ECM PEG hydrogel on Day 14 with Oil Red O staining at Day 14, Day 21, and Day 28. Zero percent ECM PEG hydrogel was not included in the adipogenesis analysis. For Oil Red O staining, the samples were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 10 min, washed with PBS and stained with 0.3% w/v% Oil Red O solution (in 60% isopropanol) for 8 min, followed by washing with 60% isopropanol for 30 s. Bright field images were taken by microscope (IX73, Olympus, USA). The samples were then de-stained with 100% isopropanol for 5 min to extract the Oil Red O according to the previous study.[18] Absorbance of the de-staining solution was measured at 510 nm wavelength using a plate reader (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices LLC, USA). The total dsDNA amount was measured using PicoGreen Assay. The absorbance ratio between Oil Red O and PicoGreen was calculated and normalized for lipase quantification study.

2.6.6. Immunofluorescence Staining of Perilipin and Semi-Quantification

Immunofluorescence study was performed based on the literature with minor modifications.[14] Briefly, all the samples were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature (RT) for 8 min, rinsed with washing buffer (Tris buffered saline containing 0.01% Triton X-100), and blocked with 10% goat serum for 0.5 h. Primary rabbit polyclonal anti-perilipin A (5 µg mL−1 in TBS containing 1% BSA) was added into the sample and incubated at RT for 1 h. The samples were rinsed thoroughly with washing buffer, incubated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody was conjugated with DyLight 650 (1 µg mL−1 in TBS with 1% BSA) for 1 h at RT. DAPI was added to visualize cell nuclei. Images were captured across the entire scaffold cross section in the triplicate samples using a fluorescence imaging system (IX73, Olympus, USA) at 20× magnification, with the exposure time 3 and 140 ms for DAPI and DyLight, respectively. The fluorescence staining images were overlaid. Encapsulated hASCs that were positive for DAPI nuclear staining and had perilipin expression within the cytoplasmic region were counted under a single-blind setup and expressed as a percentage of the total cell count based on DAPI nuclear staining.

2.7. In Vivo Characterization of Hydrogel

Twenty-four female BALB/C mice were randomly assigned to four different treatments: i) 1% ECM PEG hydrogel implantation, ii) 0.1% ECM PEG hydrogel implantation, iii) 0.01% ECM PEG hydrogel implantation, and iv) saline injection treatment. Briefly, 5 mg kg−1 ketoprofen and 0.25% bupivicaine were injected to release the pain and stress preoperatively. The mice were then anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg kg−1) xylazine (10 mg kg−1) in saline and shaved for the surgery area. A skin incision of about 0.5 cm length for each implant will be made using sharp scissors followed by blunt dissection to create a subcutaneous pocket. Meanwhile, animals in the control group will receive saline as negative controls. The implantation sites were closed with Vicryl 6–0 sutures. Four ECM PEG hydrogels were implanted into the back of each mouse (10 weeks old, BALB/c, weighting 18–21 g). The grafts were harvested and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 1, 2, and 3 weeks after surgery. All animal studies were conducted under an approved IACUC protocol.

2.8. Histological and Oil Red O Staining for Lipids Analysis

For histological examinations, specimens were embedded in OCT compound and frozen at ‒20 ˚C overnight. Samples were microtomed into 30 µm slices. The sections were washed with distilled water and then stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) and Oil Red O.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA) with one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s post hoc test and p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Protein Composition in Human Adipose Tissue–Derived ECM and ECM Distribution in ECM-PEG Hydrogel

ECM from adipose tissue was found to have a porous structure revealed by SEM (Figure 1C), consistent with previous studies.[14] LC-MS analysis indicates the extracted ECM contained some representative protein composition of the original adipose tissue.[19] Three main proteins were identified and listed in Table 1. The major components of the isolated adipose tissue comprise ample amount of Collagen I, which is identified as a typical extracellular matrix protein. COL1A1, COL1A2 had the highest rate of labeling among all investigated proteins, and constitute the triplex collagen type I fibers.[19] Collagen III is also a constituent of adipose ECM, which is found in human visceral adipocytes as well.[20]

Table 1.

Component of extracellular matrix (ECM) via LC-MS.

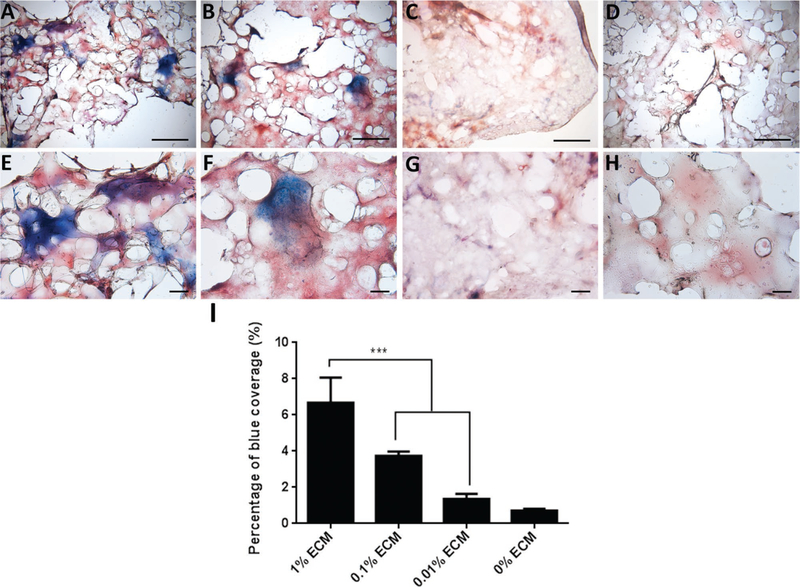

ECM PEG hydrogel was formed and pores were observed under the microscope (Figure 1D). Masson’s trichrome staining was performed to assess the distribution of ECM collagen in PEG hydrogel.[21] The area stained blue indicates the presence of collagen. All the samples containing ECM were stained blue due to the presence of collagen (Figure 2A–C,E–G), while, as expected, no blue staining was observed in 0% ECM PEG hydrogel (Figure 2D,H), which suggests the collagen component existed in ECM partially in accordance with LC-MS results. There was significantly higher collagen staining in 1% ECM PEG hydrogel group compared to 0.1% and 0.01% group (p < 0.05) (Figure 2I). The ECM, which appeared as clusters, was not homogenously distributed in each hydrogel group.

Figure 2.

Representative Masson’s trichrome staining of ECM hydrogel at A–D) 4× and E–H) 10× magnification with different ECM concentrations: A,E) 1%, B,F) 0.1%, C,G) 0.01%, and D,H) 0%. I) Blue area indicates the distribution of ECM collagen, which is statistically analyzed. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *** indicates p < 0.001. Bar: A–D) 1 mm, E–H) 100 µm.

3.2. Physical Properties of ECM PEG Hydrogels

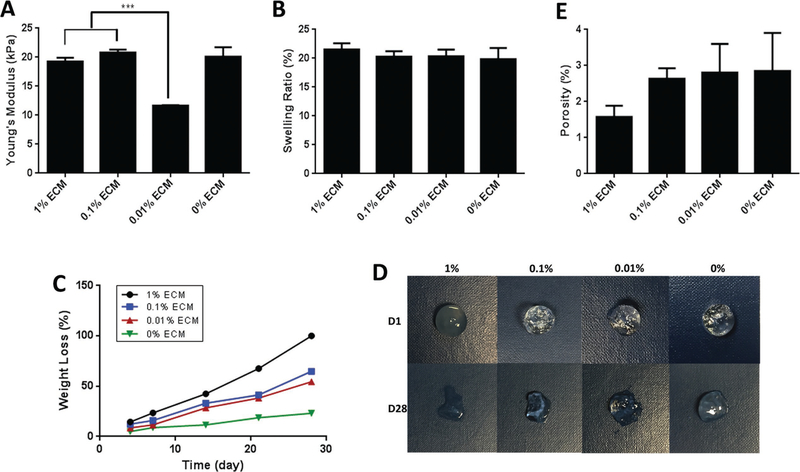

First, the scaffold’s mechanical properties were characterized as these are important parameters for adipose tissue engineering. The compressive stress–strain curve illustrated that a compressive moduli among the groups were significantly different (p < 0.05) (Figure 3A), which indicated that the addition of ECM had no negative effect on elastic modulus. The moduli of the hydrogel ranged from 11 kPa (0.01% ECM PEG hydrogel) to 20.8 kPa (0.1% ECM PEG hydrogel), likely due to the small amount of cysteine existing in collagen.[22] During polymerization, cysteine can affect the cross-linking density by forming thiol-acrylate linkages.[23]

Figure 3.

Characterization of fabricated hydrogel with different ECM concentrations: A) Compressive modulus, B) swelling ratio, C) mass loss in a degradation test, D) representative photographs of morphology changes during in vitro degradation, and E) porosity of ECM PEG hydrogels. *** indicates p < 0.001.

The swelling ratio indicates water absorption capacity and the average distance between cross-links,[24] which correlates with the rate of hydrogel degradation.[25] Liquid diffusion causes swelling of the polymers, due to the variable motion of the polymers and the free-volume among chains.[26] Swelling maximizes surface area/volume ratio and enhances the pore size, thereby facilitating infiltration of cells into the 3D scaffolds.[27] Figure 3B shows the swelling ratio of ECM PEG hydrogel. The study revealed that the 1% and 0.1% ECM PEG hydrogel groups had slightly higher swelling ratio than that of the 0.01% groups though there was no significant difference(p > 0.05). The higher ECM concentration group leads to a less cross-linked and loose structure, which consequently increased the exposure of hydrophilic polymer chains to water molecules, increased swelling ratio, and might lead to faster dry weight loss and water absorption enhancement.[28]

We next evaluate degradation rate with hydrogel incubated in PBS at 37 ˚C. As shown in Figure 3C,D, the mass loss rate increased with the higher concentration of ECM, with almost complete degradation of 1% ECM PEG hydrogel observed by 4 weeks. On the contrary, 0% ECM hydrogel remained much more intact even after 5 weeks of incubation, which may be attributable to a denser and more cross-linked structure in PEG hydrogel. The thiol group in ETTMP, and later the glutathione secreted by cells in cell study, could aid the cleavage of the disulfide bonds in ECM, resulting in a loose structure and faster degradation rate of higher concentration of ECM group.[29] The ECM incorporated hydrogel is thought to be better suited for short-term adipose tissue regeneration.

Collectively, these results suggested that the mechanical and degradation properties of ECM PEG hydrogels can be readily tuned by varying the ECM concentrations. Compressive moduli could be tuned from a few kPa to 20 kPa and the degradation rate could be varied from 3 to 5 weeks or longer. The ECM PEG hydrogel may possess a broad spectrum of properties as tissue regeneration substitutes in different situations.

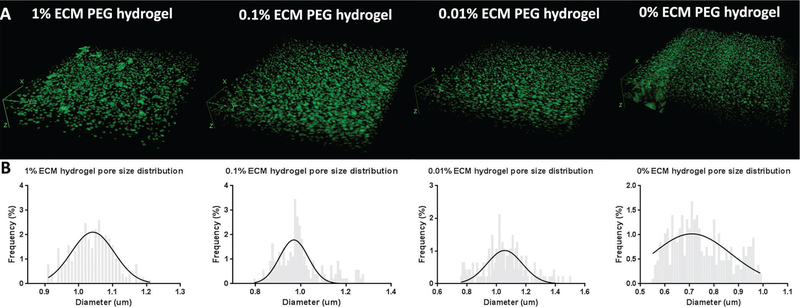

Furthermore, we sought to categorize the overall porosity and pore size of hydrogels using fluorescent labeling and MATLAB analysis technique. The 1%, 0.1%, 0.01%, and 0% ECM PEG group had a void fraction of 1.58%, 2.64%, 2.81%, and 2.85%, respectively (p > 0.05) (Figure 3E). 3D renderings of the gels using ImageJ demonstrated a continuous network of pores in all the groups (Figure 4A). The diameter of the ECM hydrogel is respectively in the range of 1.0–1.2 µm, compared to a diameter of 0.7–0.8 µm in 0% ECM (Figure 4B). The difference in pore size indicates that a higher grafting ratio of ECM results in the formation of larger pore diameters and looser network structure, which is in accordance with swelling and degradation results. FTIR analysis of the ECM containing hydrogel product shows the loss of the S–H at 2550–2600 cm−1 and the remaining presence of a characteristic C=C stretch at 1675–1600 cm−1 when compared to controls (see Figure S1, Supporting Information). The persistent C=C stretch indicates that the thiol-acrylate reaction may not proceed to completion when large volumes of ECM are incorporated into the graft. These results collectively indicate that the addition of ECM affects the polymer structure and changes the properties of hydrogel.

Figure 4.

Pore size analysis of ECM PEG hydrogel networks. A) 3D images of hydrogels with a fluorescently labeled high molecular weight dextran solution to demonstrate the interconnectivity of pores within the hydrogels. B) Pore size analysis of hydrogels. Void space varied among different groups, with 1.0 µm and 0.7–0.8 µm in PEG hydrogel with and without ECM group, respectively.

3.3. Cell Viability and Proliferation in ECM PEG Hydrogels

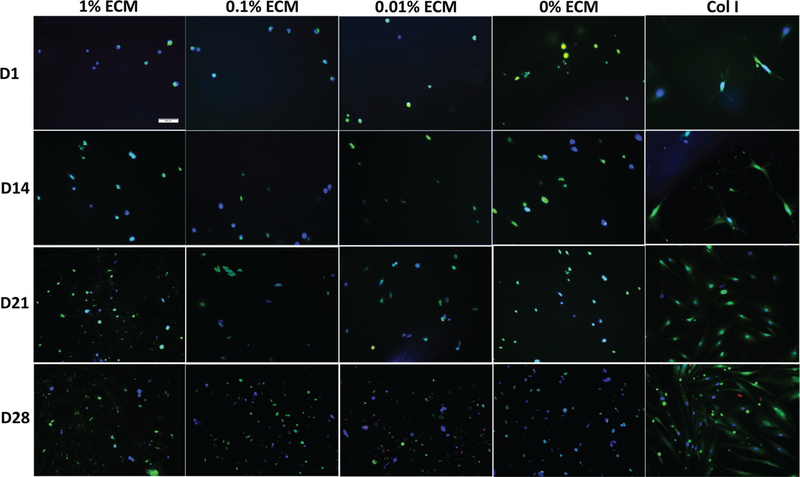

We evaluated the viability of hASCs encapsulated in ECM-PEG hydrogel by Live/Dead Staining. The viability of the encapsulated hASCs in ECM PEG hydrogels was evaluated at Day 1, 14, 21, and 28. Round shape hASCs were uniformly distributed in all the groups. hASCs maintained viability and proliferated for up to 28 days as shown in Figure 5. One percent ECM PEG group had the highest cell proliferation rate, which was demonstrated via cell counting (Figure 6B) (p < 0.05). A positive correlation between ECM concentrations and cell proliferation rate was also observed. ECM is highly porous, hydrophilic, and can be remodeled by cells. Therefore, it promotes cell migration and proliferation.[14,30] Most of the encapsulated ASCs appear to survive and proliferate in ECM PEG hydrogel. Cryo SEM analysis of the cell laden hydrogel suggests that rounded cells are present in the interconnected pore structure (see 2, Supporting Information) in agreement with fluorescent microscopy analysis. When cells are encapsulated in ECM PEG hydrogel, the interconnectivity may promote cell viability and proliferation by providing a better nutrient and waste transport. The round morphologies of hASCs in the interior were in accordance with the low stiffness of hydrogels, which promote rounded cell morphologies, and implies potential application in adipose tissue regeneration.[31]

Figure 5.

Viability of hASCs encapsulated in PEG hydrogel with different ECM concentrations at different time points. Representative live/dead fluorescence images of hASCs within different ECM PEG hydrogels (1%, 0.1%, 0.01%, and 0 %) after 1, 14, 21, and 28 days of culture, cells stained with green fluorescence are alive and red fluorescence indicate dead cells. Nucleus were stained by DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 100 µm.

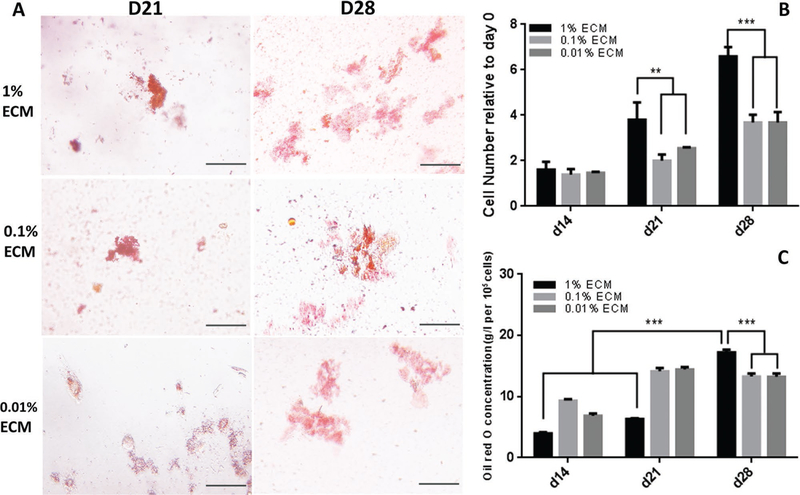

Figure 6.

Proliferation rate and adipogenic differentiation of hASCs encapsulated in ECM PEG hydrogels: A) Oil Red O staining of hASCs encapsulated in the ECM PEG hydrogel at Day 14 and then cultured for another 2 weeks in adipogenic medium. B) Cell counting using ImageJ for Live/Dead staining at Day 14, 21, and 28. C) Quantitative analysis of Oil Red O staining. ** indicates p < 0.01 and *** indicates p < 0.001. Scale bar: 100 µm.

3.4. Evaluation of In Vitro Adipogenesis of hASCs Encapsulated in ECM PEG Hydrogels

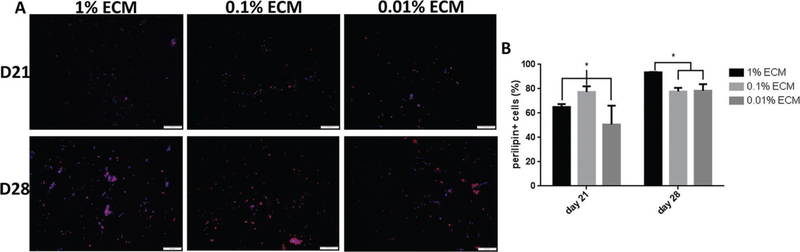

Oil Red O staining showed that hASCs encapsulated in hydrogel with higher ECM concentration group had more lipid droplets accumulation (Figure 6A). In addition, lipid accumulation increased with respect to time in culture and the Day 28 group had higher lipids accumulation compared to Day 21 time point in 1% ECM PEG hydrogel group (p < 0.05), while there is no significant difference between these two time points in both 0.1% and 0.01% groups (p > 0.05). By Day 28, 1% ECM group reaches highest lipids accumulation compared to other groups (Figure 6C) (p < 0.05), which indicates the addition of ECM upregulates adipogenesis. In addition, immunofluorescent staining of perilipin in hASCs was conducted to confirm this finding. Based on Figure 7, hydrogel containing higher ECM content showed a higher percentage of perilipin positive cells at Day 28 (p < 0.05). Perilipin is an important protein located on the surface of lipid droplets in adipocytes which is essential for lipid storage,[32] and is used for semi-quantitative analysis of ASC adipogenesis.[30] Clear trends were observed in both overlaid images (Figure 7A) and perilipin positive cell data analysis (Figure 7B) in terms of distribution of perilipin expression, and it is also consistent with the result shown in Oil Red O staining (Figure 6A,C). Hence, it can be concluded that ECM PEG hydrogel might be a suitable system for adipose tissue engineering.

Figure 7.

Assessment of perilipin expression of hASCs encapsulated in ECM PEG hydrogel through semi-quantitative analysis. All hydrogels were cultured in stromal medium for 14 days, followed by an additional 7 and 14 days in adipogenic differentiation medium. A) Representative overlaid images of perilipin (red) with DAPI (blue) counterstaining. The expression of perilipin at Day 21 is lower than that at Day 28. B) Quantification of perilipin positive cells in ECM PEG hydrogel. The expression in 1% ECM PEG hydrogel group at Day 28 is higher than that in other groups. * indicates p < 0.05. Scale bar: 200 µm.

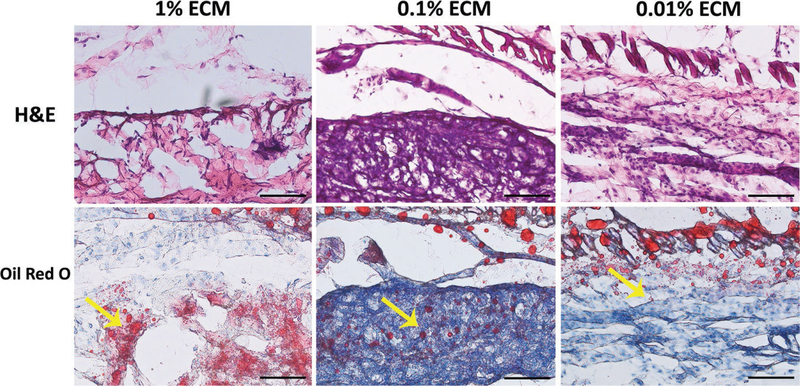

3.5. In Vivo Study

Four ECM PEG hydrogel scaffolds were implanted subcutaneously in the back of each Bal/C mouse for all treatment groups for 2 weeks. Observed behavior and weight gain were normal (3.2 ± 0.6 g) for all mice after surgery. Histological analysis (H&E staining) showed that a large number of host cells infiltrated and migrated homogeneously into the hydrogel for up to 2 weeks after subcutaneous implantation (Figure 8). No evident inflammation was found in the implant site and few inflammatery cells were found in H&E staining sections. In vivo adipogenensis was evaluated by Oil Red O staining. The results showed that Oil Red O positive area was more apparent in the 1% ECM group than the others, indicating that the addition of ECM in PEG hydrogel system can enhance adipogenesis in vivo.

Figure 8.

In vivo study on adipose regeneration of ECM PEG hydrogels at Day 14 after implantation. More lipids was found in 1% ECM group. Yellow arrow indicates the lipids. Scale bar: 100 µm.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have characterized a hybrid synthetic biological, decelluarized synthetic ECM-PEG hydrogel and evaluated its potential for adipose tissue regeneration. This system is based on a Michael addition reaction via acrylate-thiol group and demonstrated by FTIR results (see Supporting Information). With encapsulation of hASCs, our data indicated that the addition of adipose-derived ECM into PEG hydrogel will increase the hASCs proliferation rate and enhance the adipogenic differentiation capacity of hASCs. Commonly used natural polymers include collagen,[33] fibrin,[34] alginate,[35] chitosan,[36] hyaluronate,[37] agarose,[38] and others.[39] Collagen is the major component of the isolated adipose-derived ECM. This composition has well described biocompatibility and biodegradability[40] and it is likely the collagen incorporated into the graft material provides for cellular adhesion via integrin binding and in turn affects cell proliferation and fate by direct physical contacts in the hydrogel. As shown in Table 1, all the major proteins extracted belong to ECM component.[41] COL1A1 and COL1A3 is an insulin-like growth factor (IGF),[41] which has been demonstrated to stimulate adipocyte differentiation, proliferation, and trophic activities in vitro.[42] Yuksel et al. reported that local delivery of IGF-1 with PLGA/PEG microspheres has the potential to increase fat-graft survival rates, which may further influence the cellular/stromal composition of the grafted tissue.[42] It is also reported that IGF-1 enhanced the migration, promoted proliferation, and inhibited apoptosis of hASCs.[43]

In mesenchymal stem cells, adipogenic differentiation is activated by p38 kinase and inhibited by β-catenin.[44] Denatured collagen I (DC I) molecules via urea in this study might expose seven binding sites for αvβ3 and become available for interaction with integrin receptors for adipogenesis.[45] It was also reported that the level of active p38 in mesenchymal cells are high with the addition of DC I, leading to low levels of activated ERK and β-catenin.[44] That might explain why 1% ECM group had the highest adipogenesis potential shown both in Oil Red O staining (Figure 6) and perilipin immunofluorescence staining (Figure 7). This study shows higher concentration of ECM promotes cell proliferation and upregulates adipogenesis of hASCs, which might be due to the existence of Collagen I in adipose-derived ECM.

Changes in the rigidity of the substrate that cells reside in broadly regulate cell behavior and may also impact cell fate, leading to the difference in regenerative capabilities of hydrogels. ECM rigidity is mainly determined by the composition, cross-linking density, and contraction force of its protein components.[46] Increased matrix rigidity is well known to promote adipose progenitor cells’ self-renewal and angiogenic capacity.[47] Cross-linked PEG-based hydrogels are widely used due to their intrinsic low-protein adsorption properties, minimal inflammatory profile, history of safe in vivo use, ease in incorporating various functionalities, and commercial availability of reagents.[48] By using a Michael addition reaction, it offered a flexible biochemical composition, biomechanical compliance, and simplicity of in vivo use without photopolymerization or thermopolymerization procedures that typically generates toxic free radicals.[49] PEG-based hydrogels can provide sustained release of biologically active soluble factors, such as hepatocyte growth factor.[50] The stiff-ness of PEG hydrogel can be tuned by varying the amount of PEGTA, which is suitable for adipose tissue (1–10 kPa). Hydrogel mimicking the native stiffness of adipose tissue (2 kPa) significantly upregulated the expression of adipogenic markers of hASCs without the addition of exogenous adipogenic growth factors and other small molecules.[51] The stiffness (30 kPa) of ECM-PEG used in this study, which is higher than that in normal adipose tissue,[52] does not affect cell proliferation. Once exposed to adipogenic microenvironment, the hASCs encapsulated in the ECM-PEG hydrogel system were induced to adipogenesis pathway with plenty of cells and insulin growth factors inside. This study suggests that the hybrid synthetic/ECM hydrogel is biocompatible and suitable to support adipose progenitor proliferation and promote adipogenic differentiation. In addition, cell-free hydrogel system is promising because cell delivery scaffolds system faces some ethic problem which limits its application for soft tissue regeneration.

5. Conclusions

Adipose-derived ECM processed from abundant lipoaspirates, which are often discarded as medical waste, provide a potentially low-cost source of bioactive material for use in scaffold fabrication. Overall, this study demonstrated a versatile hybrid synthetic–biological graft technology for the growth and expansion of mesenchymal stem cells. The reported results have highlighted the impact of the design and incorporation of ECM for adipose tissue engineering. In addition, this hydrogel system provides a good niche for progenitor cell infiltration and proliferation after implantation, and creates a proadipogenic microenvironment in vivo. However, the volume stability and dispersion of the ECM component into the hydrogel system remains a challenge and requires further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 (DE024790) through the National Institute of Craniofacial and Dental Research and through NSF (CBET-1403301). The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Tatiana Laremore, Maxwell Turner Wetherington, John Cortina, and Bing Yao for their kind help. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Prof. Jeffrey Gimble is a co-owner, cofounder, and chief scientific officer of LaCell LLC and co-owner and cofounder of Obatala Sciences and Talaria Antibodies. These could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Dr. Shue Li, Department of Stomatology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, Millennium Science Complex, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

John Nicholas Poche, School of Medicine, Louisiana State University, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA.

Yiming Liu, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, Millennium Science Complex, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

Dr. Thomas Scherr, Department of Chemistry, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, USA

Jacob McCann, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, Millennium Science Complex, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

Anoosha Forghani, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, Millennium Science Complex, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

Mollie Smoak, Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Mitchell Muir, Department of Biological Engineering, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA.

Lisa Berntsen, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, Millennium Science Complex, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

Dr. Cong Chen, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, Millennium Science Complex, University Park, PA 16802, USA

Dr. Dino J. Ravnic, Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, PennState Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

Prof. Jeffrey Gimble, Department of Medicine and Surgery, School of Medicine, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA

Prof. Daniel J. Hayes, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, Millennium Science Complex, University Park, PA 16802, USA, djh195@engr.psu.edu

References

- [1].Chan BP, Leong KW, Eur. Spine J 2008, 17, 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhang L, Hu J, Athanasiou KA, Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2009, 37, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wu I, Nahas Z, Kimmerling KA, Rosson GD, Elisseeff JH, Plast. Reconstr. Surg 2012, 129, 1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brandl F, Sommer F, Goepferich A, Biomaterials 2007, 28, 134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bauer-Kreisel P, Goepferich A, Blunk T, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2010, 62, 798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Baglio SR, Pegtel DM, Baldini N, Front Physiol 2012, 3, 359; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kim JS, Choi JS, Cho YW, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 8581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Chen FM, Wu LA, Zhang M, Zhang R, Sun HH, Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3189; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lih E, Park KW, Chun SY, Kim H, Kwon TG, Joung YK, Han DK, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 21145; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ju YM, Atala A, Yoo JJ, Lee SJ, Acta Biomater 2014, 10, 4332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Vacanti CA, J. Cell Mol. Med 2006, 10, 569; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shue L, Yufeng Z, Mony U, Biomatter 2012, 2, 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Vempati P, Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS, PLoS One 2010, 5, e11860; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tabata Y, Tissue Eng 2003, 9, S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yu C, Bianco J, Brown C, Fuetterer L, Watkins JF, Samani A, Flynn LE, Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Flynn L, Prestwich GD, Semple JL, Woodhouse KA, Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3834; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Flynn L, Prestwich GD, Semple JL, Woodhouse KA, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 89, 929; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Flynn LE, Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Turner AE, Yu C, Bianco J, Watkins JF, Flynn LE, Biomaterials 2012, 33, 4490; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Flynn LE, Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Uriel S, Huang JJ, Moya ML, Francis ME, Wang R, Chang SY, Cheng MH, Brey EM, Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3712; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brown BN, Freund JM, Han L, Rubin JP, Reing JE, Jeffries EM, Wolf MT, Tottey S, Barnes CA, Ratner BD, Badylak SF, Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2011, 17, 411; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang L, Johnson JA, Zhang Q, Beahm EK, Acta Biomater 2013, 9, 8921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cheung HK, Han TT, Marecak DM, Watkins JF, Amsden BG, Flynn LE, Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pritchard CD, O’Shea TM, Siegwart DJ, Calo E, Anderson DG, Reynolds FM, Thomas JA, Slotkin JR, Woodard EJ, Langer R, Biomaterials 2011, 32, 587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee S, Tong X, Yang F, Acta Biomater 2014, 10, 4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Caldwell AS, Campbell GT, Shekiro KMT, Anseth KS, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2017, 6, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shaik S, Hayes D, Gimble J, Devireddy R, Stem Cells Dev 2017, 26, 608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mariman EC, Wang P, Cell Mol. Life Sci 2010, 67, 1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Alvarez-Llamas G, Szalowska E, de Vries MP, Weening D, Landman K, Hoek A, Wolffenbuttel BH, Roelofsen H, Vonk RJ, Mol. Cell Proteomics 2007, 6, 589; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang P, Mariman E, Keijer J, Bouwman F, Noben JP, Robben J, Renes J, Cell Mol. Life Sci 2004, 61, 2405; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Roelofsen H, Dijkstra M, Weening D, de Vries MP, Hoek A, Vonk RJ, Mol. Cell Proteomics 2009, 8, 316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hong Y, Huber A, Takanari K, Amoroso NJ, Hashizume R, Badylak SF, Wagner WR, Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zou X, Feng B, Dong T, Yan G, Tan B, Shen H, Huang A, Zhang X, Zhang M, Yang P, Zheng M, Zhang Y, J. Proteomics 2013, 94, 473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gupta N, Lin BF, Campos LM, Dimitriou MD, Hikita ST, Treat ND, Tirrell MV, Clegg DO, Kramer EJ, Hawker CJ, Nat. Chem 2010, 2, 138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Peppas NA, Huang Y, Torres-Lugo M, Ward JH, Zhang J, Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2000, 2, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Browning MB, Cereceres SN, Luong PT, Cosgriff-Hernandez EM, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2014, 102, 4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Maya S, Indulekha S, Sukhithasri V, Smitha KT, Nair SV, Jayakumar R, Biswas R, Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2012, 51, 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Praveen G, Sreerekha PR, Menon D, Nair SV, Chennazhi KP, Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 095102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tan H, Ramirez CM, Miljkovic N, Li H, Rubin JP, Marra KG, Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kar M, Vernon Shih YR, Velez DO, Cabrales P, Varghese S, Bio-materials 2016, 77, 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brown CF, Yan J, Han TT, Marecak DM, Amsden BG, Flynn LE, Biomed. Mater 2015, 10, 045010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wen JH, Vincent LG, Fuhrmann A, Choi YS, Hribar KC, Taylor-Weiner H, Chen S, Engler AJ, Nat. Mater 2014, 13, 979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Greenberg AS, Egan JJ, Wek SA, Garty NB, Blanchette-Mackie EJ, Londos C, J. Biol. Chem 1991, 266, 11341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Capito RM, Spector M, Gene Ther 2007, 14, 721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ahmed TA, Dare EV, Hincke M, Tissue Eng. Part B Rev 2008, 14, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rouillard AD, Berglund CM, Lee JY, Polacheck WJ, Tsui Y, Bonassar LJ, Kirby BJ, Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2011, 17, 173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cheng M, Cao W, Gao Y, Gong Y, Zhao N, Zhang X, J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed 2003, 14, 1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chung C, Beecham M, Mauck RL, Burdick JA, Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Alaminos M, Del Carmen Sanchez-Quevedo M, Munoz-Avila JI, Serrano D, Medialdea S, Carreras I, Campos A, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 2006, 47, 3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Van Nieuwenhove I, Tytgat L, Ryx M, Blondeel P, Stillaert F, Thienpont H, Ottevaere H, Dubruel P, Van Vlierberghe S, Acta Biomater 2017, 63, 37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee KY, Mooney DJ, Chem. Rev 2001, 101, 1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Halberg N, Wernstedt-Asterholm I, Scherer PE, Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am 2008, 37, 753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yuksel E, Weinfeld AB, Cleek R, Wamsley S, Jensen J, Boutros S, Waugh JM, Shenaq SM, Spira M, Plast. Reconstr. Surg 2000, 105, 1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhu MX, Feng Y, Dangelmajer S, Guerrero-Cazares H, Chaichana KL, Smith CL, Levchenko A, Lei T, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Stem Cells Dev 2015, 24, 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mauney J, Volloch V, Matrix Biol 2009, 28, 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Volloch V, Olsen BR, Matrix Biol 2013, 32, 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL, Science 2005, 310, 1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chandler EM, Berglund CM, Lee JS, Polacheck WJ, Gleghorn JP, Kirby BJ, Fischbach C, Biotechnol. Bioeng 2011, 108, 1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Phelps EA, Enemchukwu NO, Fiore VF, Sy JC, Murthy N, Sulchek TA, Barker TH, Garcia AJ, Adv. Mater 2012, 24, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Garber L, Chen C, Kilchrist KV, Bounds C, Pojman JA, Hayes D, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101, 3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhao J, Zhang N, Prestwich GD, Wen X, Macromol. Biosci 2008, 8, 836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Young DA, Choi YS, Engler AJ, Christman KL, Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zhao W, Li X, Liu X, Zhang N, Wen X, Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl 2014, 40, 316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.