Abstract

Background

While many cessation programmes are available to assist smokers in quitting, research suggests that support from individual partners, family members, or 'buddies' may encourage abstinence.

Objectives

To determine if an intervention to enhance one‐to‐one partner support for smokers attempting to quit improves smoking cessation outcomes, compared with cessation interventions lacking a partner‐support component.

Search methods

We limited the search to the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register, which was updated in April 2018. This includes the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE (via OVID); Embase (via OVID); and PsycINFO (via OVID). The search terms used were smoking (prevention, control, therapy), smoking cessation and support (family, marriage, spouse, partner, sexual partner, buddy, friend, cohabitant and co‐worker). We also reviewed the bibliographies of all included articles for additional trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials recruiting people who smoked. Trials were eligible if they had at least one treatment arm that included a smoking cessation intervention with a partner‐support component, compared to a control condition providing behavioural support of similar intensity, without a partner‐support component. Trials were also required to report smoking cessation at six months follow‐up or more.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently identified the included studies from the search results, and extracted data using a structured form. A third review author helped resolve discrepancies, in line with standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Smoking abstinence, biochemically verified where possible, was the primary outcome measure and was extracted at two post‐treatment intervals where possible: at six to nine months and at 12 months or longer. We used a random‐effects model to pool risk ratios from each study and estimate a summary effect.

Main results

Our update search identified 465 citations, which we assessed for eligibility. Three new studies met the criteria for inclusion, giving a total of 14 included studies (n = 3370). The definition of partner varied among the studies. We compared partner support versus control interventions at six‐ to nine‐month follow‐up and at 12 or more months follow‐up. We also examined outcomes among three subgroups: interventions targeting relatives, friends or coworkers; interventions targeting spouses or cohabiting partners; and interventions targeting fellow cessation programme participants. All studies gave self‐reported smoking cessation rates, with limited biochemical verification of abstinence. The pooled risk ratio (RR) for abstinence was 0.97 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.83 to 1.14; 12 studies; 2818 participants) at six to nine months, and 1.04 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.22; 7 studies; 2573 participants) at 12 months or more post‐treatment. Of the 11 studies that measured partner support at follow‐up, only two reported a significant increase in partner support in the intervention groups. One of these studies reported a significant increase in partner support in the intervention group, but smokers' reports of partner support received did not differ significantly. We judged one of the included studies to be at high risk of selection bias, but a sensitivity analysis suggests that this did not have an impact on the results. There were also potential issues with detection bias due to a lack of validation of abstinence in five of the 14 studies; however, this is not apparent in the statistically homogeneous results across studies. Using the GRADE system we rated the overall quality of the evidence for the two primary outcomes as low. We downgraded due to the risk of bias, as we judged studies with a high weighting in analyses to be at a high risk of detection bias. In addition, a study in both analyses was insufficiently randomised. We also downgraded the quality of the evidence for indirectness, as very few studies provided any evidence that the interventions tested actually increased the amount of partner support received by participants in the relevant intervention group.

Authors' conclusions

Interventions that aim to enhance partner support appear to have no impact on increasing long‐term abstinence from smoking. However, most interventions that assessed partner support showed no evidence that the interventions actually achieved their aim and increased support from partners for smoking cessation. Future research should therefore focus on developing behavioural interventions that actually increase partner support, and test this in small‐scale studies, before large trials assessing the impact on smoking cessation can be justified.

Keywords: Humans, Family, Friends, Social Support, Spouses, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Smoking Cessation, Smoking Cessation/methods, Smoking Cessation/psychology, Smoking Cessation/statistics & numerical data, Time Factors

Plain language summary

Do interventions to enhance one‐to‐one support provided by partners, family members, or 'buddies' help smokers quit?

Background

Smokers are more likely to quit when others in their social circle quit. They are also more likely to be successful when they receive active support to quit. Life partners, family members, friends, and others are all viable sources of support. This review investigated whether interventions designed to train or guide individuals to provide support to smokers trying to quit helped more smokers to quit than stop‐smoking programmes without a partner‐support element.

Study characteristics

This is an update of previous reviews. We searched for studies published up to April 2018, and found three new studies that we could include, giving a total of 14 studies with 3370 participants. Studies had to be randomised controlled trials that recruited smokers trying to quit, and measured whether participants had quit smoking at least six months after the beginning of the study. The study had to include at least one group who were part of a stop‐smoking programme to increase partner support, and at least one group who received a comparable stop‐smoking programme without partner support. Most of the studies were conducted in the USA. At recruitment the average amount participants smoked was between 13 to 29 cigarettes a day across studies. The smoking status of partners providing support varied, but most were non‐smokers. Intervention techniques ranged from low to high intensity; in some cases help was by a self‐help booklet and in other cases by face‐to‐face counselling. In some studies researchers did not make direct contact with 'partners' and the smokers themselves were encouraged to find a 'buddy', but in other studies both the smoker and their 'buddy' received face‐to‐face support.

Key results

We combined 12 studies (2818 participants) to measure successful quitting at six to nine months follow‐up, and seven studies (2573 participants) to measure quitting at 12‐month follow‐up. Partner support did not increase the chances of stopping smoking at either time point. We also split the studies in each analysis based on the type of partner giving support (relatives/friends/co‐workers versus spouses/cohabiting partners versus fellow cessation‐programme participants). There was no difference in quit rates between study groups, regardless of the type of partner providing the support. Only one study reported that partner support improved more in the group given the partner‐support intervention than in the group where no partner‐support intervention was provided. Another study reported that partner support improved more in a more intensive partner‐support intervention than a less intensive partner‐support intervention.

Quality of the evidence

We rated the overall quality of the evidence as low. This is because there were problems with the design of some of the studies. A number of important studies only used participant self‐report to measure if people had quit smoking, and there is a chance that these reports may have been inaccurate. Also, very few studies found that the intervention actually increased the level of partner support that participants received. This review therefore cannot tell us whether receiving more support from a partner can help a person to give up smoking.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Cessation interventions with a partner support component compared to cessation interventions without a partner support component for people who want to quit smoking.

| Smoking cessation interventions with a partner support component compared to smoking cessation interventions without a partner support component for people who want to quit smoking | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who smoked and were willing to be recruited to a cessation programme Setting: Varied (community, medical, worksite) Intervention: Smoking cessation interventions with a partner support component Comparison: Smoking cessation interventions without a partner support component | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Absolute effect of interventions with no partner support component | Absolute effect of interventions with partner support component | |||||

| Long‐term smoking abstinence (6 to 9 months) | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.83 to 1.14) | 2818 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,b | ‐ | |

| 168 per 1000 | 163 per 1000 (139 to 191) | |||||

| Long‐term smoking abstinence (12 months+) | Study population | RR 1.04 (0.88 to 1.22) | 2573 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW b,c | ‐ | |

| 176 per 1000 | 183 per 1000 (155 to 215) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. We deemed three of the studies contributing to this meta‐analysis to be at a high risk of detection bias, as the level of support differed between intervention arms, and the abstinence outcome was not biochemically verified. One of these studies (McBride 2004) received the highest weighting in the analysis. Another of these studies was also at a high risk of selection bias as randomisation was not carried out optimally (Gruder 1993). bDowngraded one level due to indirectness. Of the studies that measured increase in partner support, most found that the partner support intervention did not increase the amount of support received by participants. The studies in this review were therefore not necessarily measuring the effect of interventions which successfully increased partner support for smokers who wanted to quit. cDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. We deemed four of the studies contributing to this meta‐analysis to be at a high risk of detection bias, as the level of support differed between intervention arms, and the abstinence outcome was not biochemically verified. Two of these studies (Bastian 2012; McBride 2004) received high weightings in the analysis. Another of these studies was also at a high risk of selection bias as randomisation was not carried out optimally (Gruder 1993).

Background

Despite the decrease in smoking prevalence in many high‐income countries over the past 30 years, the number of tobacco users in middle‐ and low‐income countries is on the rise. Tobacco remains the leading cause of preventable death in the USA (CDC 2014). Globally, tobacco use is estimated to kill more than 7 million people annually (WHO 2017). Although effective cessation interventions exist, their overall effect is modest and they do not reach many high‐risk users (Fiore 2008).

The initiation and maintenance of tobacco use is strongly influenced by social groups and family members. Longitudinal findings suggest that these influences might be causal. Christakis 2008 examined the impact of social networks on smoking cessation. They assessed cigarette‐smoking behaviour repeatedly among a densely‐interconnected social network of 12,067 people from 1971 to 2003 as part of the Framingham Heart Study. Smoking cessation rates among the social network varied by relationship types. If one person in a mutually‐perceived friendship stopped smoking, the other person was 43% less likely to continue smoking. Co‐workers in small firms where they were likely to know each other were 34% less likely to smoke if a co‐worker quit smoking. They also found that among married couples, when one spouse stopped smoking, the other spouse was 67% less likely to continue to smoke, and husbands and wives affected each other similarly.

Other studies on the role of spouses and cohabiting partners accord with the Framingham Heart Study findings. Spousal support alone may positively influence quitting. Married smokers have higher quit rates than those who are divorced, widowed or have never married (Waldron 1989; Yong 2014). However, quitting remains challenging for married or partnered individuals. A study among the USA working population reported that 65% of smokers who were married or lived with a partner were interested in quitting, with 54% making a quit attempt in the past year but with only 6.8% successful in quitting (Yong 2014). The smoking status of cohabiting partners and family members is important, because living with a smoker can make it less likely for an individual to quit (Homish 2005; Shoham 2007). Smokers who are married to nonsmokers or ex‐smokers are more likely to quit and remain abstinent (Hanson 1990; Macy 2007; McBride 1998; Waldron 1989). In addition, Monden 2003 found that a smoker was more likely to quit if his/her partner had quit smoking in the past than if his/her partner had never smoked.

Social support is designed to bolster an individual's ability to cope with stress and involves providing both psychological and material resources (Cohen 2004). It comprises three types of resources: instrumental, informational, and emotional (House 1985). Co‐operative behaviours, such as persuading a smoker not to smoke a cigarette, and reinforcement, such as expressing pleasure at a smoker's efforts to quit, have been found to predict successful quitting (Coppotelli 1985; Mermelstein 1983; Roski 1996). Negative behaviours, such as nagging a smoker and complaining about smoking, do not appear to increase smokers’ chances of quitting (Coppotelli 1985) and are associated with earlier relapse (Roski 1996).

Family and social support has been shown to be an effective intervention for improving other health behaviours, such as dietary changes (Scholz 2013), weight reduction (Wang 2014) and medication compliance (DiMatteo 2004). Importantly, family approaches have been effective in the treatment of other addictions, especially alcohol and drug dependence (Baldwin 2012; Powers 2008). Family interventions or programmes have become a standard part of most substance abuse programmes (Ruff 2010).

Supportive interventions can take several forms. Some interventions employ individuals as coaches who assist partners, family members, or buddies to make health behaviour changes, while other interventions focus on changing risk behaviours among both members of the pair (Baucom 2012). In the former approach, partners may or may not be attempting health behaviour changes. The results of studies examining the impact of social support for smoking cessation from family members, friends, co‐workers and 'buddies' have, however, been mixed (May 2006; May 2007; McMahon 2000; Morgan 1988) and two previous systematic reviews (Hemsing 2012; May 2000) did not find that partner intervention increased smoking cessation.

Objectives

To determine if an intervention to enhance one‐to‐one partner support increases smoking cessation rates, when compared to a comparable smoking‐cessation intervention without a partner‐support component.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Smokers of either gender and any age, irrespective of their initial level of nicotine dependence, recruited from any setting, who agreed to participate in a smoking cessation programme. Participants who smoked were paired with either a spouse, another family member, a friend, a co‐worker or another individual identified by the smoking‐cessation programme to provide support for quitting. Participants could be motivated to quit or not, and supportive partners could be non‐smokers or smokers.

Types of interventions

Studies included interventions that facilitated one‐to‐one smoking‐cessation support for smokers, through spouses, other family members, friends, 'buddies', co‐workers or fellow treatment participants. A partner‐support intervention could be directed at the smoker, at the partner or at both, with the aim of assisting smokers to quit. Examples include, training smokers in obtaining social support, encouraging increased contacts between smokers and supportive partners, providing training or written materials to partners to assist them in engaging in supportive behaviours, and intervening with smoker and partner pairs in couples therapy. This review differs slightly from earlier versions (Park 2002; Park 2004a; Park 2012), which did not specify that interventions had to facilitate one‐to‐one partner support. We decided to narrow the definition of this review to exclude studies on the impact of receiving support from a group of people and to focus on one‐to‐one support from a single partner. This is because studies investigating the impact of group therapy for smoking cessation are included in a separate review (Stead 2017). Hence, this update does not include one study that had been included in earlier versions of this review, that facilitated mutual support among groups of individuals by a telephone‐contact system (Powell 1981). However, we did include studies where interventions were delivered in a group setting if partner support was provided by a single person, on a one‐to‐one basis.

Control conditions consisted of a comparable smoking‐cessation intervention to the treatment condition, but without a partner‐support element.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome was abstinence in the target smoker (not the partner). The outcome was either self‐reported or biochemically‐verified abstinence (carbon monoxide levels, saliva cotinine/thiocyanate), assessed at least six months post baseline. We preferred validated abstinence over self‐reported abstinence. We collected abstinence outcomes at two post‐treatment intervals where available: at six to nine months, and at 12 months or more.

Our secondary outcome was the intermediate outcome of level of partner support, as assessed by the Partner Interaction Questionnaire (PIQ) or Support Provided Measure (SPM).

Search methods for identification of studies

For this update, we limited the search to the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register, which we searched in April 2018. The Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE (via OVID); Embase (via OVID); PsycINFO (via OVID), and clinicaltrials.gov, to the end of March 2018. See full search strategies and list of other resources searched to compile the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register on the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's website. To identify reports of trials relevant to this review, we used the following topic‐related terms in the title or abstract: family OR families OR marriage OR spouse OR partner OR sexual partner OR buddy OR friend OR cohabitee OR co‐worker. The Group's Information Specialist prescreened records retrieved by this search, to exclude those in which the presence of these terms was not related to the review topic. We also checked the bibliographies of all included articles for additional trials.

This strategy replaces previous specific searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO, combining smoking‐related and topic‐related terms. For earlier versions of this review we had conducted searches of the following databases:

CDC Tobacco Information and Prevention Database (March 2004)

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1966 to July 2000)

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC)

PsycLIT

Dissertation Abstracts (1861 to December 1999)

HealthStar (1975 to July 2000)

Cancer Lit (1966 to April 2004)

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) (1972 to April 2004)

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

To identify potentially relevant studies, two review authors (from BF, TS, or KR) independently prescreened all titles and abstracts obtained by the search, using a screening checklist based on our eligibility criteria. We resolved disagreements by referral to a third review author (either BF, TS, or KR). Two review authors (from BF, TS, or KR) obtained and independently screened full‐text versions of the potentially relevant papers for inclusion, resolving any disagreements by referral to a third review author (from BF, TS, or KR).

Data extraction and management

Pairs of review authors (BF,TS, KR, EWP) independently extracted data for each study using a structured form. We then compared and consolidated the extracted data, with a third review author (BF, TS, or KR) resolving any discrepancies. We extracted the following data from each included study: study design and randomisation methods, numbers of participants, participant characteristics, details of the intervention(s) and control(s), primary and secondary outcome definitions and data, and loss to follow‐up. We used reported data to calculate intention‐to‐treat (ITT) outcomes, in which all participants randomised to study conditions were included in outcome analyses (if not reported in this manner by authors). We excluded participants reported as deceased from the analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool to examine potential bias in four domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding (detection bias); and incomplete outcome data (Higgins 2011). We assessed each study as either at low, unclear or high risk of bias for each of the four domains. As the interventions eligible for inclusion in this review are behavioural, it was impossible to blind study personnel and participants to the content of the interventions. We therefore focused solely on the risk of detection bias rather than performance bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We used risk ratios to calculate individual study abstinence outcomes at six to nine months post‐treatment, and 12 months or more post‐treatment.

Dealing with missing data

We conducted analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis, where participants lost to follow‐up were assumed to be smokers. We excluded participants reported as deceased, as is standard in the field.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity in our meta‐analyses. We considered an I2 of 50% or higher to be substantial statistical heterogeneity. We also considered clinical and methodological variability across the studies when assessing methods of pooling studies.

Data synthesis

We estimated a pooled, weighted average, using risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for our two abstinence outcomes, using the Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects model. We chose random‐effects because of the clinical heterogeneity across studies, i.e. there was substantial variation across the interventions tested, and the types of partners offering support.

We summarised the data on level of partner support achieved narratively.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Our protocol (Park 2001) did not prespecify any subgroup or sensitivity analyses. However, we decided to carry out a post hoc subgroup analysis, dividing the studies by type of partner targeted by interventions, as this was a key source of clinical heterogeneity across studies. Specifically, we present results for three subgroups of studies: interventions targeting relatives, friends or co‐workers; interventions targeting spouses or cohabiting partners; and interventions targeting fellow cessation‐programme participants.

We also carried out sensitivity analyses to judge the effect of removing a study with a low‐contact control group not ideally matched to the intervention group, which we judged to be at high risk of selection bias, on abstinence at long‐term follow‐ups (Gruder 1993).

'Summary of findings' table

Following standard Cochrane methodology, we created a 'Summary of findings' table for our smoking abstinence outcomes: 1) measured between six and nine months follow‐up, and 2) at 12 months follow‐up or longer. Also following standard Cochrane methodology, we used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome, and to draw conclusions about the quality of evidence.

Results

Description of studies

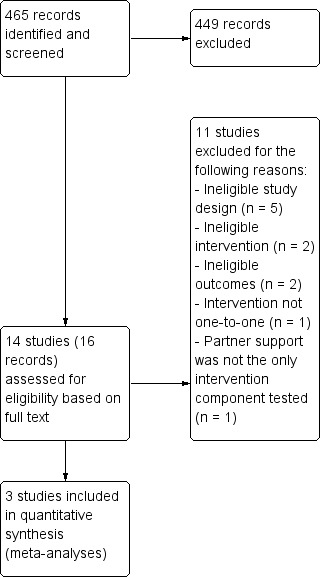

We identified 456 citations from the search of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register for this update of the review. We deemed three new studies to be eligible for inclusion in this update (Bastian 2012; LaChance 2015; Nichter 2016). This gives a total of 14 included studies. Nyborg 1986 has been split for the purposes of meta‐analysis into Nyborg 1986a and Nyborg 1986b; for more details of all included studies refer to Characteristics of included studies. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow chart for this update. We carried out full‐text review of 16 records reporting 14 studies. We excluded 11 studies because they failed to meet eligibility criteria. We have also excluded one of the previously‐included studies, due to a change in inclusion criteria, described above (Powell 1981). We excluded most of the studies because, in addition to a partner intervention, the intervention group received other smoking cessation interventions that were not received by the control group. However, we excluded other studies because they did not have a minimum follow‐up period of six months (e.g. Albrecht 1998; Andersen 2006; Gardner 1982; Loke 2005; West 1998), and because the support intervention did not identify a partner for support (e.g. Halpern 2015; Powell 1981). For more details of the reasons for study exclusion refer to Characteristics of excluded studies.

1.

Flow diagram illustrating how studies were identified for the current update only

The 14 included studies were published between 1984 and 2016, covering a total of 3370 unique participants (1665 intervention and 1705 control). The number of participants per study ranged from 24 to over 1000. The Nyborg trial (Nyborg 1986a; Nyborg 1986b) has been given two separate study IDs because of the complexity of the intervention method which included a 'therapist‐administered couples intervention' and a 'self‐administered or minimal‐contact couples intervention'.

Twelve of the 14 studies were conducted in the USA, and the two remaining in Indonesia and the UK. Seven studies recruited participants from the community, five recruited participants from medical settings and two recruited from work sites. The average age of smokers among the 14 studies ranged from 25 to 59. One study reported that the minimum age was less than 18 years (Orleans 1991). The average number of cigarettes smoked by participants at baseline ranged from 13 to 29 per day across included studies. One study enrolled pregnant women, some of whom had already quit spontaneously (McBride 2004).

The smoking status of 'partners' varied, but most were non‐smokers. Partners were defined in three major categories, based on each study's specific eligibility criteria:

Relative, friend, or co‐worker (Bastian 2012; Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; Gruder 1993; Nichter 2016; Orleans 1991; Patten 2009; Patten 2012);

Spouse or cohabiting partner (LaChance 2015; McBride 2004; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Nyborg 1986a; Nyborg 1986b);

Fellow cessation programme participants (Malott 1984; May 2006).

Most of the studies included in this analysis provided smoking cessation interventions to the smoker, with an additional partner‐support component. The partner‐support interventions themselves were directed at the smoker or the partner or both, to increase support for cessation. However, two studies provided the study intervention directly to the partner and study staff did not directly provide smoking cessation assistance to the smoker (Patten 2009; Patten 2012). In these studies, the partner received a booklet and five weeks of telephone counselling (Patten 2009), and a booklet and five weeks of support‐skills training through a web‐based chat room (Patten 2012).

The intensity of intervention techniques ranged from low‐ to high‐intensity interventions. In the least intensive intervention, booklets (designed to be a four‐week programme) were mailed to smokers who were encouraged to provide them to 'allies' (Orleans 1991). In another study, smokers received five smoking‐cessation telephone calls over approximately five months and the partner intervention was a booklet provided to smokers who were coached on how to enlist support to quit from others (Bastian 2012).

Two studies provided smoking cessation interventions to the smoker, and support‐person training by telephone (McBride 2004; Nyborg 1986a). These telephone‐based studies consisted of six counselling sessions for pregnant women and their partners delivered during pregnancy and the first four months postpartum (McBride 2004), and an eight‐week programme (Nyborg 1986a) respectively.

Three studies provided in‐person counselling to the smoker and support person (LaChance 2015; Nichter 2016; Nyborg 1986b). Two of these studies focused on couples; one included seven weeks of behavioural couples therapy for the partner‐support intervention (LaChance 2015), and the other included eight weeks of couples training on smoking cessation (Nyborg 1986b). In the third study, physicians provided smoking cessation messaging over the course of tuberculosis treatment and supporters were trained in a three‐ to four‐hour session and given booster training (Nichter 2016).

In five studies participants attended group sessions spanning four to six weeks (Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; Gruder 1993; Malott 1984; May 2006) and partners attended one to three of these group sessions (Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; Gruder 1993), or participants were assigned a ‘buddy’ from the group (Malott 1984; May 2006) who provided one‐to‐one support. In two of these studies, the partner received two additional follow‐up calls from the counsellor (Glasgow 1986; Gruder 1993).

In addition to telephone or in‐person or group‐counselling, materials provided for the support partner included information booklets or manuals (Bastian 2012; Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; Gruder 1993; LaChance 2015; Malott 1984; McBride 2004; Nyborg 1986a), monitoring booklets (Malott 1984), and video recordings (Ginsberg 1992; McBride 2004).

As specified in our inclusion criteria, in general control groups were given the same support as the intervention group, but without the partner‐support element. Control groups were therefore generally defined as 'no contact' with a partner. However, group sessions with other quitters were used in some studies (May 2006; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986), as well as weekly telephone contact with a therapist in others (Bastian 2012; Nyborg 1986a; Nyborg 1986b). Across studies, control groups consisted of one or more of the following components: self‐help manual or instruction; health education; nicotine gum; television programmes; weekly group meetings or contact with therapist; and psychotherapy. Gruder 1993 was borderline eligible for this review as both potential control arms were not ideal comparators to test the effect of the partner‐support interventions ('social support' group). The first was a 'no contact' control, but although this was described as 'no contact' participants did receive a self‐help manual and instructions to watch a smoking‐cessation television programme (20‐day programme). The second arm was a 'discussion group' where participants were also asked to bring along a 'buddy' who received contacts from the investigators but was not given specific instructions on how to be helpful. As the second group could also be categorised as a 'partner support' intervention we did not use that group as a control and used the 'no contact' group. However, it is important to note that while this group did receive smoking cessation support this was not matched with the level of support provided in the intervention arm. We therefore carried out a sensitivity analysis to judge the effect of removing this study from our analyses.

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed each study for risks of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011).

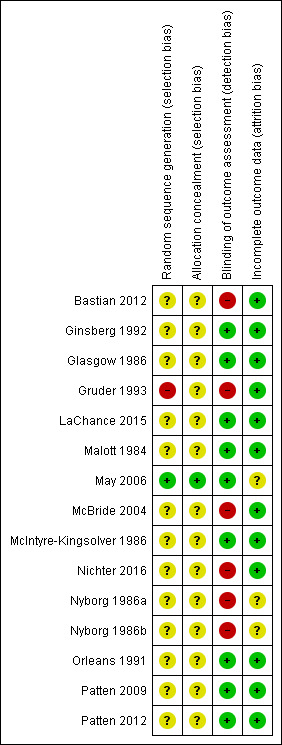

Figure 2 summarises the review authors’ judgements for each domain by study (although Nyborg 1986a and Nyborg 1986b are included in the figure as two separate study IDs, with study arms separated for the purpose of meta‐analysis, they refer to one study). The Characteristics of included studies table gives more detail on how we made decisions on individual studies. We deemed most studies to be at an unclear risk of bias for at least one domain, and rated five studies to be at a high risk of bias for at least one domain.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Random sequence generation

All of the studies stated that they were randomised controlled trials, but 12 of the 14 studies (Bastian 2012; Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; LaChance 2015; Malott 1984; McBride 2004; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Nichter 2016; Nyborg 1986a/Nyborg 1986b; Orleans 1991; Patten 2009; Patten 2012) did not provide information on how they generated the randomisation allocation sequence, and we therefore judged them to be at unclear risk of selection bias. Of the two remaining studies, we rated Gruder 1993 at high risk, as 'no contact' controls were randomised first, and trialists then tried to contact the remaining people who had registered their interest. Only those who still showed an interest in the study were randomised to the two experimental conditions. This may have led to differences between the participants in the control condition and the two experimental conditions. We judged May 2006 to be at low risk, as they created their allocation sequence using computerised random‐number generation.

Allocation concealment

Again, only May 2006 specified that researchers had been blinded to participant allocation prior to the start of treatment, and we therefore deemed it to be at low risk of selection bias for this domain. We rated the remaining studies at unclear risk, as they did not describe their methods of allocation concealment.

Blinding (detection bias)

All studies involved behavioural interventions, which renders blinding of providers and participants impossible. For this reason we did not assess performance bias and focused our examination of blinding on detection bias only. We judged nine of the 14 studies to be at low risk of detection bias (Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; LaChance 2015; Malott 1984; May 2006; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Orleans 1991; Patten 2009; Patten 2012). In all cases this was because biochemical validation of abstinence occurred, reducing the chances of differential reporting resulting from knowledge of the allocated treatment. We judged the remaining five studies (Bastian 2012; Gruder 1993; McBride 2004; Nichter 2016; Nyborg 1986a/Nyborg 1986b) to be at high risk of bias, as biochemical verification was not used to confirm quit rates and there were different levels of support/intervention components between intervention and control arms that may have influenced abstinence‐reporting. These differences were a necessary element of the studies, as all intervention groups received an additional partner‐support component that the control groups did not receive.

Incomplete outcome data

Two studies (May 2006; Nyborg 1986a/Nyborg 1986b) failed to provide information on the number of participants lost to follow‐up, and we therefore rated these at an unclear risk of attrition bias. The remaining studies (Bastian 2012; Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; LaChance 2015; Malott 1984; McBride 2004; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Nichter 2016; Orleans 1991; Patten 2009; Patten 2012) all reported overall loss to follow‐up as below 50% and similar between arms, except for Gruder 1993 who reported 51% loss to follow‐up at 24‐month follow‐up. However, as it was so close to 50%, and there was no differences in loss to follow‐up between groups with loss to follow‐up lower at earlier follow‐ups, we judged this to be at low risk of attrition bias alongside the other 11 studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Twelve studies reported outcomes at six to nine months (Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; Gruder 1993; LaChance 2015; Malott 1984; May 2006; McBride 2004; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Nyborg 1986a/Nyborg 1986b; Orleans 1991; Patten 2009; Patten 2012). These studies reported abstinence rates of 0% to 42% for the intervention groups and 0% to 46% for control groups. The highest cessation rates were from two small studies (Ginsberg 1992; LaChance 2015): 35% and 42% in the intervention groups, and 45% and 48% in the control groups respectively. McBride 2004 also reported high abstinence rates, at 37% in the intervention group and 36% in the control group. Participants were women recruited in early pregnancy, some of whom had already quit. Four studies reported abstinence rates of 17% to 27% in the intervention group and 0% to 25% in the control group (Glasgow 1986; Malott 1984; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Nyborg 1986a). One study (Patten 2012) reported a cessation rate of less than 17% for the intervention group and of more than 30% in the control group. The remaining five studies had cessation rates of less than 17% for both intervention and control groups (Gruder 1993; Orleans 1991; Patten 2009; May 2006; Nyborg 1986a).

Seven studies reported abstinence rates at 12 months or more (Bastian 2012; Ginsberg 1992; Gruder 1993; McBride 2004; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Nichter 2016; Orleans 1991). These ranged from 4% to 36% for intervention groups and 2% to 33% for control groups.

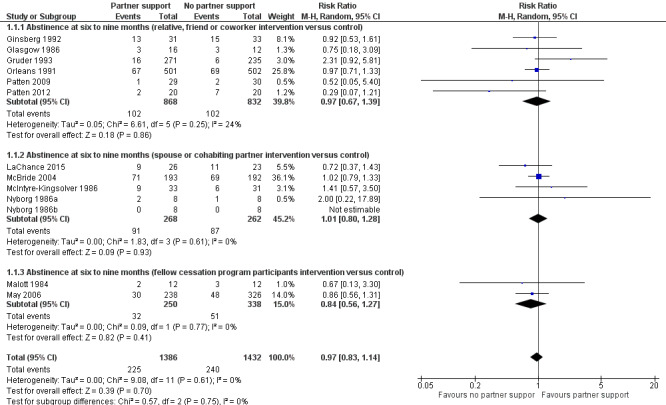

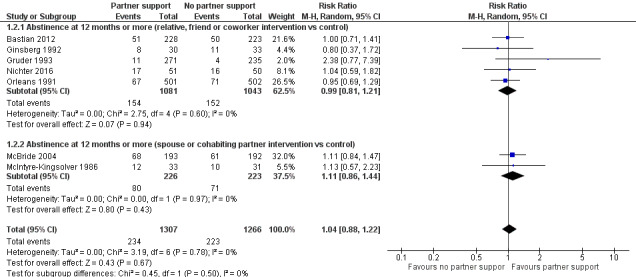

There was variation between studies in terms of type of partner and type or intensity of intervention used. Consequently, we used a Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects model to pool study effect estimates. This generated pooled risk ratios (RRs) for the effect of the intervention on abstinence at six to nine months follow‐up and at 12 months follow‐up or longer. There was no evidence of an effect at either follow‐up point. At six to nine months the RR was 0.97 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.14, 12 studies; 2818 participants; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.1). Subgroup analysis at six to nine months yielded similar results. Interventions targeting relatives, friends or co‐workers versus control: RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.39, 6 studies; 1700 participants; I2 = 24%); interventions targeting spouses or cohabiting partners versus control: RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.28, 4 studies; 530 participants; I2 = 0%; and interventions targeting fellow cessation‐programme participants versus control; RR 0.84 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.27, 2 studies; 588 participants; I2 = 0%) (Figure 3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Partner intervention versus control, Outcome 1 Abstinence at six to nine months.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Partner intervention versus control, outcome: 1.1 Abstinence at six to nine months.

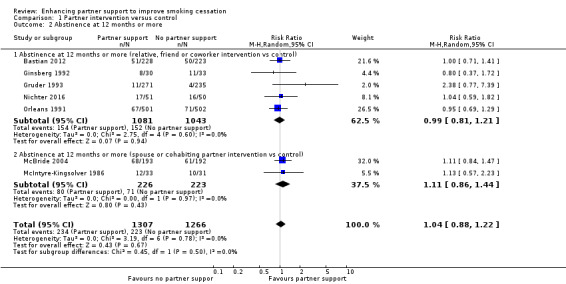

At 12 months or more the RR was 1.04 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.22, 7 studies; 2573 participants; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.2). There was also no evidence of an effect between the subgroups at 12 months. Interventions targeting relatives, friends or co‐workers versus control: RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.21, 5 studies; 2124 participants; I2 = 0%); interventions targeting spouses or cohabiting partners versus control: RR 1.11 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.44, 2 studies; 449 participants; I2 = 0%) (Figure 4).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Partner intervention versus control, Outcome 2 Abstinence at 12 months or more.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Partner intervention versus control, outcome: 1.2 Abstinence at 12 months or more.

We carried out sensitivity analyses to test the effect of removing Gruder 1993 from our two meta‐analyses. There were two reasons that we thought this was necessary: firstly, the control group for this study was not exactly as specified in our inclusion criteria, as participants did not receive the same smoking cessation as the intervention group minus the partner‐support component (although they did receive a smoking cessation intervention); secondly, the study was the only one rated at high risk of selection bias, as the randomisation procedures were flawed. These analyses resulted in an RR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.11) for six‐ to nine‐month abstinence, and an RR of 1.02 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.20) for 12‐month abstinence. These results are both comparable with the original analyses and do not have an impact on interpretation.

Eleven studies used a validated scale or selected items from scales to assess partner support. Nine studies used versions of the Partner Interaction Questionnaire (PIQ) (Bastian 2012; Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; Gruder 1993; LaChance 2015; Malott 1984; McBride 2004; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Orleans 1991), and two studies used the Support Provided Measure (SPM) (Patten 2009; Patten 2012). Only one of the 11 studies that measured partner support reported that support increased in the intervention group relative to the control at follow‐up. Ginsberg 1992 found that the support condition resulted in greater reinforcement, co‐operation and helpfulness at week four, and less policing at month 12 than did the other conditions. In addition, there was a significant partner support for quitting by treatment interaction at month 12. Although Gruder 1993 did not measure the difference in partner support between the intervention and control groups used in this review, they did measure the difference in partner support between the intervention group ('social support' group) and a less intensive partner‐support intervention ('discussion group'). They found that the participants in the 'social support' condition had higher levels of post‐intervention support than did those in the 'discussion' condition. They also found that the PIQ‐20 ratio was statistically significant in predicting cessation (z = 2.35, P < 0.02), suggesting that the 'social support' condition enhanced cessation through increasing levels of social support. As the control condition used for this study was even less intensive than the 'discussion' condition, it is possible that partner support in the intervention group would have been greater than any incidental partner support received by the control group. However, the analyses conducted by Gruder 1993 were based on a subset of participants (fewer than 50% of participants in each condition) who attended at least one treatment session and who were present at the last group session to complete the PIQ. Hence this analysis is based on data affected by attrition bias.

One study (Patten 2012) reported a significant increase in partner support in the intervention group, but smokers' reports of partner support received did not differ significantly. Two studies (Bastian 2012; Glasgow 1986) did not report their PIQ score changes or differences between the groups. The remaining six studies, reported no difference in post‐intervention partner support between the intervention and control groups (LaChance 2015; Malott 1984; McBride 2004; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Orleans 1991; Patten 2009).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We added three randomised controlled trials evaluating smoking cessation at six months or more for this update of the review, giving a total of 14 included studies. The conclusions of this review have not substantially changed since the last publication (Park 2012). A meta‐analysis that pooled the results of 12 studies including 2818 participants showed that smokers who received an intervention designed to boost partner support were not more likely to be abstinent from cigarettes at six to nine months follow‐up than smokers who did not receive a partner‐support intervention. Similarly, a meta‐analysis that pooled the results of seven studies (2573 participants) at 12‐month follow‐up or more found no significant increase in smoking cessation among participants in the intervention arm compared to participants in the control arm. We did not detect any treatment effect when studies were divided into subgroups defined by the type of partner that was targeted for intervention.

The failure to conclusively show an effect of partner support on smoking cessation in our meta‐analyses may not necessarily mean that all partner‐support interventions will be ineffective in increasing abstinence rates. A number of issues should be taken into account, and are discussed below.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Only two studies, of the 11 that measured it, demonstrated a positive effect of treatment on measures of partner support. Failure to demonstrate efficacy may therefore be because most interventions did not actually increase the partner support received by smokers. This is supported by the two studies that found that smoking outcomes appeared to be mediated by the actual level of partner support achieved (Ginsberg 1992; Gruder 1993). It is therefore hard to say whether there was no effect on cessation because partner‐support interventions do not work overall, or because the interventions tested were not capable of increasing the level of support provided to smokers trying to quit. It could be that interventions which are successful in increasing the partner support received by smokers could increase the likelihood of those smokers quitting. However, this means that work needs to be done to identify interventions that successfully increase partner support, and these in turn need to be tested.

The interventions included in this review may have been too simplistic. The interventions primarily focused on how partners could encourage smokers to quit or avoid discouraging quit attempts. Smoking is a complex behaviour that is affected by societal influences, romantic and familial relationships, friendships and social groups, and biological and psychological factors. Functional social support is associated with adherence to medical treatment and other health outcomes (DiMatteo 2004). By definition, functional support includes not only emotional support but also informational and instrumental support (Cohen 2004). Future interventions could more systematically build partner capacity to provide all forms of functional support to assist smokers across multiple aspects of the smoking cessation process, such as how to obtain and adhere to cessation medications.

In many cases it is also possible that partner support interventions were overwhelmed by non‐experimental treatment components. Most interventions were tested in designs that included a variety of other behavioural‐support components across both treatment conditions, e.g. partner support + control intervention(s) versus control intervention(s) (Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; May 2006; McBride 2004; Nyborg 1986b; Orleans 1991). In these studies, the partner‐support component may have been relatively weak compared to the other intervention and control components, especially in those studies that used minimal booklet‐based or one‐shot partner‐support interventions (May 2006; McBride 2004; Nyborg 1986b; Orleans 1991). Future studies could benefit from minimising the other elements comprising the 'platform' control intervention, in order to enhance the possibility of detecting the undiluted effects of the partner‐support component. Indeed, Westmaas 2002 suggests that partner support be tested against a minimal treatment (e.g. booklets).

Westmaas 2002 also points out other methodological limitations that undermine the strength of existing studies, or our ability to detect intervention effects. These include failure to measure baseline support, failure to verify participants’ engagement with peer support, failure to measure perceived support among smokers, the use of small samples in many studies, and failure to biologically verify abstinence.

Last, the smoking status of partners is an important factor in cessation, but it varied across the studies included in this review. Smokers who are in relationships with non‐smokers may have higher quitting success rates (Chandola 2004), and former smokers with partners who smoke have been found to be more likely to relapse (Kahn 2002). These data suggest that a non‐smoking partner might provide the most effective support for smokers, which is consistent with partner‐support interventions for other addictions. For example, LaChance 2015 noted that behavioural couples therapy (BCT) for alcohol use disorders typically excludes couples in which both are using, in order to capitalise on the non‐using partner's ability to model and reinforce abstinence in the using partner. Only two of the trials included in this review required both partners to be smokers (Malott 1984; May 2006). These were both studies that paired fellow participants in smoking cessation programmes to provide support. These partners, however, were presumably new acquaintances at the onset of the studies and may not have been able to provide the intensity or quality of support of a friend, a co‐worker, or a cohabiting partner. Hence, further studies investigating the importance of the smoking status of partners offering smoking cessation support, alongside the nature of the relationship between partner‐support couples, appears warranted.

Quality of the evidence

Our risk of bias ratings varied across studies and domains. Most studies were at unclear risk of selection bias, as methods of sequence generation and allocation concealment were not described clearly. This may be a reporting issue rather than bias actually being present. However, we rated one study at high risk of selection bias, as participants were randomised in two separate stages that may have influenced the characteristics of the populations from which participants were selected (Gruder 1993). We carried out a sensitivity analysis to measure the effect of excluding this study on the analyses and found that its exclusion did not influence the results or their interpretation. Another issue affecting our bias assessment was that almost half (five of 14) of the included studies did not biochemically verify abstinence rates, or did not report validated rates. This left these studies at risk of detection bias, as participants may have felt more pressure to succeed in the intervention arm where they were being supported by a partner, leading to a higher chance of misreporting. However, this is not supported by the very low levels of statistical heterogeneity across analyses. We judged studies to be mostly at low risk of attrition bias, due to generally low levels of loss to follow‐up and with similar losses between study arms. We rated only two studies at unclear risk due to a lack of reporting (May 2006; Nyborg 1986a/Nyborg 1986b).

Using GRADE standards, we judged the quality of the evidence to be low for both of our long‐term abstinence outcomes (six to nine months; 12 months or longer), meaning our confidence in the effect estimates is limited. We downgraded the evidence contributing to both outcomes for two reasons. The first of these was risk of bias. We judged a number of studies in both meta‐analyses to be at high risk of detection bias, and two of these were weighted highly in the analyses (Bastian 2012; McBride 2004). Furthermore, the randomisation procedures for another study (Gruder 1993), included in both analyses, were not sufficient to guarantee adequate randomisation. The second reason relates to indirectness. As described above, very few studies demonstrated any effect of the intervention on the partner support received. The results of this review therefore suggest that interventions that do not successfully increase partner support may be no more effective than interventions without components designed to enhance partner support, rather than illustrating the effect of successfully‐enhanced partner support on smoking cessation rates.

Potential biases in the review process

This field of research is growing slowly, and relatively few studies met our inclusion criteria. We believe that the review process was robust and did not introduce any additional biases. For outcome assessment, we followed the standard methods used for Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group cessation reviews, such as carrying out an intention‐to‐treat analysis, assuming those lost to follow‐up are smoking. For this update we searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register as is standard. We identified two relevant observational studies (Luscher 2017a; Luscher 2017b), which were not eligible for inclusion in this review. However, there may be unpublished data that our searches did not uncover, as is always a risk.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Two other reviews of partner support for smoking cessation have been conducted. May 2000 critically reviewed evidence about the use of 'buddy' systems. The review included seven of the studies that we include (Ginsberg 1992; Glasgow 1986; Gruder 1993; Malott 1984; McIntyre‐Kingsolver 1986; Nyborg 1986a/Nyborg 1986b; Orleans 1991) and three that we excluded from our review because they failed to meet our inclusion criteria (Albrecht 1998; Mermelstein 1983; West 1998). May 2000 did not conduct a meta‐analyses because they deemed the intervention approaches to be too diverse. Their systematic review found the quality of many of the studies to be poor, but they suggested that the use of 'buddies' in the context of a smoking cessation clinic might be useful. Hemsing 2012 conducted a systematic review of interventions to enhance partner support for smoking reduction, quit attempts, or cessation among pregnant or postpartum women and their partners. Nine studies met their review criteria, of which four were designed to enhance mothers' smoking cessation. They included only one of the studies that we included (McBride 2004) and three additional studies (Aveyard 2005; Campion 1994; De Vries 2006) that did not meet our criteria for this review. Their review found that none of the four studies achieved a significant difference between intervention and control groups for smoking cessation among pregnant women. Both reviews agreed that more evidence is needed (a conclusion also supported by our review).

In a review of social support in smoking cessation, Westmaas 2010 suggested that the lack of significant effect detected in studies of social‐support interventions may be due to a 'ceiling effect', whereby established treatments given to both the intervention and control groups may have adequately met smokers' support needs. Social support could therefore be helpful for those who lack social support going into a smoking cessation programme, whereas for those who already have a functional social‐support system social support might not be helpful. Manipulating or augmenting social relationships might be effective for some and not for others (Graham 2017). Investigators should use interventions, control conditions, and eligibility criteria that ensure that their support‐building interventions bring added value to smokers’ social environments related to quitting.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We did not detect an increase in smoking quit rates in groups receiving interventions designed to enhance partner support when quitting smoking, compared with control groups who received a smoking cessation intervention without a partner‐support component. Further data from included studies suggest that these interventions did not increase the level of support received by smokers, which may have influenced this lack of effect. We therefore cannot draw firm conclusions about the direct impact of increased partner support on smoking cessation.

Implications for research.

More work needs to go into developing partner‐support interventions, paying more attention to the quality of the partner interaction and the types of partners involved, with the aim of increasing the amount of partner support provided to the smoker. Interventions should be tested to ensure they increase partner support before large trials testing cessation are justified. Where successful interventions are identified, they should go on to be tested in adequately‐powered, high‐quality cessation studies, whilst controlling for pre‐existing support and partner smoking status, with Ievels of partner support routinely measured as an intermediate outcome. Cessation rates should also be biochemically validated, in order to minimise the risk of differential inaccurate self‐reporting between trial arms.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 September 2018 | Amended | Funding information updated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2001 Review first published: Issue 1, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 April 2018 | New search has been performed | Search updated (April 2018), 3 new randomised trials included. Definition of review inclusion criteria changed to exclude studies on the impact of group support and focus on one‐to‐one support from a single partner. Hence, 1 previously included study (Powell 1981) now excluded |

| 21 April 2018 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Review updated with 3 new included studies (1 previously included study removed); text updated; conclusions unchanged |

| 30 April 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Review updated with two new included studies found; text updated; conclusions unchanged. |

| 30 April 2012 | New search has been performed | A total of 12 new articles were found in the updated search in December 2011, and two randomised trials that satisfied the inclusion criteria were included. Minor update to body of the review, conclusions not changed. |

| 17 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 25 February 2008 | New search has been performed | A total of 10 new articles were found in the updated search in October 2007, and two included randomised trials that satisfied the inclusion criteria. A minor update has been made to the body of the review and the conclusions remain as before. |

| 11 May 2004 | New search has been performed | A total of nine new articles were found in the updated search in April 2004, but none included randomised trials that satisfied the inclusion criteria. No changes have been made to the body of the review and the conclusions remain as before. |

Acknowledgements

Fred G. Tudiver, Thomas Campbell, Jennifer Shultz and Lorne Becker were authors on previous versions of this review. We want to thank Jamie Hartmann‐Boyce, who helped run the searches for this update, Jonathan Livingstone‐Banks for his guidance throughout this process, and Nicola Lindson for editing drafts and providing guidance on revisions.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure and Cochrane Programme Grant to the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Partner intervention versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence at six to nine months | 13 | 2818 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.83, 1.14] |

| 1.1 Abstinence at six to nine months (relative, friend or coworker intervention versus control) | 6 | 1700 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.67, 1.39] |

| 1.2 Abstinence at six to nine months (spouse or cohabiting partner intervention versus control) | 5 | 530 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.80, 1.28] |

| 1.3 Abstinence at six to nine months (fellow cessation program participants intervention versus control) | 2 | 588 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.56, 1.27] |

| 2 Abstinence at 12 months or more | 7 | 2573 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.88, 1.22] |

| 2.1 Abstinence at 12 months or more (relative, friend or coworker intervention vs control) | 5 | 2124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.81, 1.21] |

| 2.2 Abstinence at 12 months or more (spouse or cohabiting partner intervention vs control) | 2 | 449 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.86, 1.44] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bastian 2012.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Study dates: February 2008 ‐ February 2010 VA Medical Centre, USA |

|

| Participants | 471 current smokers planning to quit in the next 30 days, receiving treatment for chronic illnesses (i.e. cancer, CVD, HTN, diabetes, COPD), able to identify a support person (defined as a relative or a friend that the participant felt would support them the most to quit smoking) Mean age 59.2. 91.5% male, HSI 2.8 46.9% of support persons were spouses or significant others; 27.8% of support persons currently smoke |

|

| Interventions | (1) Standard telephone counselling (5 sessions using CBT format); NRT, Quit Kit (smoking cessation resources and items) (n = 236) (2) Family‐supported intervention: Standard telephone counselling; family support booklet plus additional telephone counselling content focusing on social support skill and setting at least 1 additional support‐related goal each counselling session (n = 235) |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: self‐reported 7‐day point prevalence cessation at 5 months post‐randomisation Secondary outcome: self‐reported 7‐day point prevalence cessation at 12 months post‐randomisation |

|

| Notes | New study for 2018 Update. Funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs (IIR‐05‐202) Author declarations: "SCG serves as a consultant to Gilead Sciences and Watermark Research Partners. Although these relationships are not perceived to represent a conflict with the present work, it is included in the spirit of full disclosure" |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "We used blocked randomisation, stratified by sex and disease type". However, the method of sequence generation was not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of concealment was not described. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | The intervention arms had different amounts of support, as the intervention arm received extra telephone counselling content in addition to standard telephone counselling; we therefore rated the risk of detection bias as high. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Non‐respondents to follow‐up interviews and postcards, excluding deaths, were treated as smokers in analyses". The study used an ITT analysis in which all participants (except those who died) were included in all outcome analyses. Loss to follow‐up was low and similar in both arms and few deaths occurred. |

Ginsberg 1992.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Study dates: 1985‐1986 Community volunteers, USA |

|

| Participants | 64 smokers, 46% male, mean age 38.2 yrs Mean number of cigarettes smoked per day 25.6 Partner = spouses/intimate others (64%), friends (33%), relatives (3%) 66% non‐smoking partners | |

| Interventions | (1) Nicotine gum + psychotherapy: 2 mg nicotine gum, instructions for gum use and education materials, quitting strategy selection, relapse prevention skill training, public commitment to abstinence, costs/benefits exercise, and psycho‐educational materials (4 week programme) (n = 33) (2) Nicotine gum + psychotherapy + PS: as for (1) + partner empathy exercise, PS video tape, PS strategy booklet, personalised support strategy, and signed support agreements (5‐week programme) (n = 31) | |

| Outcomes | CO test at weeks 0, 4, 12, 26 & 52. Biochemical analysis of urine cotinine & thiocyanate at weeks 26 & 52. Written questionnaire, self‐report |

|

| Notes | For purposes of this analysis, we dropped a nicotine‐only group (n = 35), and used the nicotine gum + psychotherapy group as the control. We excluded one participant who died from the denominator in our meta‐analysis. Funded by the American Cancer Society (Grant PBRJ) and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Research Scientist Development Award (DA00065) Author declarations: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Subjects were randomly assigned to three to six member groups in order of entrance into treatment within time constraints. Treatment for each group was randomly selected with the constraint that each cohort [of nine] have one group of each condition and an equal number of smoking partners across conditions". Method of sequence generation not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "At each assessment, subjects completed a written questionnaire (Table 3), reported the number of cigarettes smoked in the past week, and provided expired air samples for carbon monoxide measurement. At Weeks 26 and 52 they also provided urine for biochemical analyses" As smoking cessation outcomes were verified using exhaled CO and urinary cotinine we rate the risk of detection bias as low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 9 participants lost to follow‐up counted as smokers. 1 participant who died was excluded from analyses by authors, and for the purposes of this review. |

Glasgow 1986.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Study dates: Not stated Worksite smoking programme; random group assignment |

|

| Participants | 29 smokers, 31% male, mean age 33.5 yrs Mean number of cigarettes smoked per day 25.5 Partner: Significant other outside of work setting (spouse, close friend) % non‐smoking partners not stated | |

| Interventions | (1) Basic programme: 6 weekly group meetings (n = 13) (2) Basic programme + Social Support condition: 6 weekly group meetings, partner provided support during non‐work hours, partners received a support manual in bi‐weekly instalments (6‐week programme) (n = 16) | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reports, examine and weigh saved cigarette butts, and 2 biochemical measures of smoking exposure (CO and saliva thiocyanate). Pre‐test, post‐test and 6‐month follow‐up | |

| Notes | Funded by grants #30615 and #33739 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Author declarations: not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Randomly assigned" No further information given |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Smoking cessation outcomes were assessed using exhaled CO |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Six‐month follow‐up data were collected on 93% of subjects completing treatment, with no differences between conditions". |

Gruder 1993.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Study dates: Not stated Community volunteers in Illinois, USA; random assignment by site |

|

| Participants | 793 (only 506 in study arms relevant to this review analysis) smokers 38% male, mean age 42.3 yrs Mean cigarettes smoked per day 28 Partner: 'buddy'. 100% non‐smoking partner |

|

| Interventions | (1) No‐contact control group: received self‐help manual and instructions to watch a TV programme (20‐day programme) (n = 235). (2) Social support (SS): Received all components of group 1. Also received a Quitters guide, attended 3 weekly 90‐minute group meetings during 20 days and received 2 leader‐initiated phone calls 1 and 2 months after programme ended, and were to bring a non‐smoking buddy to the second group meeting. Buddies received a 'buddy guide' and were instructed how to be helpful during their group meeting. Smokers received instruction on how to get help from buddies and neutralise unhelpful people (20‐day programme) (n = 271) The study also randomised people to a 'Discussion' arm where participants were asked to bring a buddy along who therefore engaged in the programme, but were not given advice on how to be helpful. We did not use data from this group in our analyses |

|

| Outcomes | Self‐report abstinence rates only. Attempts were made to validate these rates by using saliva cotinine, but this was unsuccessful. MA uses point prevalence abstinence at 6 and 12 months | |

| Notes | The study attempted to validate quit rates by saliva cotinine, but many participants refused and so self‐reported rates were used. We used the strictest abstinence data from Table 2 for our meta‐analysis. Funded by the National Cancer Institute (Grant CA42760) Author declarations: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Authors indicate that participants were "randomly assigned". However, no‐contact controls were randomised first (as no further contact was required), then experimenters attempted to contact the remaining people who had registered their interest. Only those who still showed an interest in the study were randomised to the 2 experimental conditions. This may have led to differences between the participants in the control condition and the 2 experimental conditions. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Level of contact differed between trial arms, so we rated the risk of detection bias as high. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "...no significant difference in attrition rates by condition for all subsequent interviews" Overall, 464/793 (59%) were interviewed at 6‐month follow‐up and 385/793 (49%) at 24‐month follow‐up. High loss to follow‐up but authors addressed this in their analyses. |

LaChance 2015.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Study dates: Not stated Community volunteers (location of study not specified) |

|

| Participants | 49 smokers; had to be at least 18 years old; smoking at least 10 cigarettes per day for at least 1 year; in a heterosexual marriage or cohabiting romantic relationship for at least 1 year; willing to use and have no contraindications for nicotine patch. Partners of eligible smokers had to be at least 18 years old; non‐smokers; willing to participate; have an expired CO level of < 10 ppm Mean age 42.8; 65.2% male; mean cigarettes per day 18.1 Support persons were non‐smokers |

|

| Interventions | (1) Standard Treatment (ST): counselling: Individually‐delivered to participants only, 7 weekly 60‐minute sessions. "Smoking cessation treatment was individually delivered... Sessions focused on learning behaviours and skills associated with quitting". "To match on time and attention, the ST condition contained an extended module on relaxation training"; 8 weeks of nicotine patch therapy; self‐help materials that included instructions on how to enlist social support, consistent with standard practices used in community smoking‐cessation programmes (n = 23). (2) Behavioural Couples Therapy counselling: Delivered to participants and their partners over 7 weekly 60‐minute sessions. Sessions included completing a written agreement for quitting, role play, and assigning activities for the couples to do together outside of the sessions, teaching the couple basic communication skills and conflict resolution behaviours, and providing an overview of progressive muscle relaxation. "The couple was asked to consider behaviours that provided positive support (encouragement) and/or negative support (reminding, questioning), create a menu of support behaviours tailored to reinforce the smoker’s efforts to quit, and consider how they had used support behaviours over the previous weeks"; 8 weeks of nicotine patch therapy and BCT‐S (behavioural Couples Therapy social support smoking cessation intervention) workbook that provided an overview of the treatment approach, session format, and all handouts" (n = 26) |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Biochemically‐verified 7‐day point prevalence cessation at 6 months follow‐up | |

| Notes | New study for 2018 update Funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01 DA021265 to Heather LaChance); partially supported by NIDA (Grant T32 DA016184 to Patricia A. Cioe), the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health (Grant T32 HL076134‐07 to Erin Tooley), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (award to Timothy J. O’Farrell) Author declarations: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | An urn randomisation procedure was used to probabilistically balance the experimental and control groups on 3 potential prognostic factors: gender, nicotine dependence, and relationship happiness. No further information given |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The authors do not describe the method of allocation concealment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The primary outcome was biochemically verified, so we rated the risk of detection bias as low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Month six follow‐up was 20/26 (76.9%) in the intervention vs 18/23 (78.3%) in the control group. Loss to follow‐up was low and similar between study arms. |

Malott 1984.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Study dates: Not stated. Worksite, USA |

|

| Participants | 24 smokers, 17% male, mean age 34 yrs; mean number of cigarettes smoked per day 24 Partner: same sex, co‐workers % non‐smoking partner not stated | |

| Interventions | (1) Standard controlled smoking: 6 weekly group meetings ‐ 50 minutes each (6‐week programme) (n = 12) (2) Controlled smoking + PS: 6 weekly group meetings, received Partners Controlled Smoking Manual, and monitoring booklets were used (6‐week programme) (n = 12) | |

| Outcomes | Self‐report, lab analysis of spent cigarette butts, CO tests, and post‐treatment questionnaire. 6‐month follow‐up | |

| Notes | Funded by Grant #30615 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Author declarations: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Authors stated only that participants were randomly assigned "Groups were randomly assigned", and gave no further information about how the sequence was generated. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Self‐reported abstinence was verified with exhaled CO. We therefore judge the risk of detection bias as low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Only 1 participant lost to follow‐up in the standard control group |

May 2006.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Study dates:1999‐2000 Group treatment programme at smoker's clinic; random assignment by group |

|

| Participants | 564 smokers, 38% male, mean age 43.6 yrs; mean number of cigarettes smoked per day 23 Partner: smoker attending same cessation group | |

| Interventions | (1) Control condition: 6 weekly 1 to 1½ hour group sessions (n = 326, 20 groups) (2) Buddy condition: Buddy system was used (choosing someone in a group to be a buddy). Buddy intervention occurred during final 20 minutes of 2nd session (n = 238, 14 groups) | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reports, CO test at weeks 0, 1, 4, 26. | |

| Notes | NRT or bupropion was not withheld. 4 buddy groups and 2 solo groups used NRT or bupropion. Funding source: not reported Author declarations: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were "assigned consecutive numbers and each number was randomised by computer random number generation to the ‘buddy’ or ‘solo’ condition". |