Abstract

Aims and Objectives:

The objective of this analysis was to clarify the concepts of apathy and passivity in the context of dementia by identifying distinguishing and overlapping attributes for both concepts simultaneously.

Background:

Apathy is among the most common and persistent symptoms in dementia. The concept of apathy is often used interchangeably with passivity. Understanding similarities and differences between these concepts is of critical importance in clarifying clinical diagnostic criteria, developing consistent measurement in research, and translating research evidence into nursing practice.

Design:

A systematic literature search of multiple databases identified relevant articles for review. A modified combination of Haase et al.’s simultaneous concept analysis method and Morses’ principle-based concept analysis using qualitative content and thematic analysis procedures was applied to identify overlapping and distinguishing attributes.

Methods:

A search of PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychINFO databases identified 176 articles meeting inclusion criteria. The concepts of apathy and passivity were characterized using a standardized manual to identify attributes of definitions (conceptual and operational), related conditions, functional, behavioral and neurobiological correlates, antecedents, and consequences. Thematic analysis identified common themes across each category which were tabulated and entered into comparative matrices to identify overlapping and distinguishing features.

Results:

There is considerable overlap across attributes of apathy and passivity. Apathy is distinguished as a clinical syndrome characterized by loss of motivation not due to emotional distress or cognitive impairment. Passivity is distinguished as a lack of interaction between the individual and environment in the context of cognitive impairment.

Conclusion:

In contrast to passivity, apathy is a more robustly defined concept focused on motivational limitations within the individual associated with specific neuroanatomical deficits.

Keywords: Dementia, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, Apathy, Passivity, Concept Analysis

INTRODUCTION

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) are a core feature of neurodegenerative dementias experienced by virtually all individuals with dementia at some point during the disease trajectory (Gitlin, Kales, & Lyketsos, 2012). These symptoms are often classified as being behavioral, emotional and psychological in nature and are associated with a range of serious negative outcomes including reduced functioning, reduced quality of life, and decreased time to institutionalization (Lyketsos, 2015; Tun, Murman, Long, Colenda, & von Eye, 2007; Wancata, Windhaber, Krautgartner, & Alexandrowicz, 2003; Yaffe et al., 2002). Apathy, in particular, is a common and persistent NPS in dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases and is primarily described as a loss of motivation. Apathy in dementia is associated with a range of adverse outcomes including cognitive decline, increased risk for nursing home placement, and significant distress for family caregivers (Massimo et al., 2009). Apathy also has a strong association with mortality and a negative impact on management of comorbid conditions and disability (van der Linde, Matthews, Dening, & Brayne, 2017). Passivity or “passive behavior” is a similar concept that has been studied in the field of dementia and refers to a “reduction of energy, drive and initiative.” Because passivity often leads to increased social isolation and inactivity, passive behaviors are widely understood to increase risk for accelerated cognitive and functional decline (Harwood, Barker, Ownby, & Duara, 2000).

Various definitions of apathy have been proposed, and the concept of apathy has evolved over time. The concept was first introduced by Marin and colleagues (1991) as a “motivational impairment.” This definition’s focus on amotivation has been criticized due to the difficultly in quantifying ‘lack of motivation’ and the omission of other sources of apathetic behavior. In 2006, Levy and Dubois proposed to define apathy as “the quantitative reduction” of voluntary and purposeful behavior and proposed three underlying mechanisms responsible for apathetic behavior including impaired initiation, impaired planning, and compromised emotional-affective processing. More recent attempts to define apathy include diagnostic criteria focused on the evaluation of the behavioral, cognitive, and affective domains of apathy (Robert et al., 2009). Despite these proposed diagnostic criteria (2009), a recent review identified ongoing inconsistent use of the definition and measurement of the apathy (Lanctôt et al., 2017).

Passivity has been defined similarly to and used interchangeably with apathy, and in some instances, apathy has been described as a component of passivity (Kolanowski, 1995). In situations in which apathy has been designated as an element of passivity, passive behaviors have been described as representing a more extensive deterioration in interactions with others and surroundings (Colling, 2004). However, descriptions of passivity and apathy in reference to one another have been inconsistent, limiting conceptual and theoretical clarity regarding the differences and similarities between the two concepts. Nurses are often in an optimal position to identify behavioral symptoms in dementia and changes indicative of apathy or passivity. However, lack of distinction between these two concepts hampers nurses’ and informal caregivers’ ability to identify and evaluate appropriate interventions.AIMS

Precise classification of NPS is critical to the development and translation of clinical research evidence to guide nurses in identifying target symptoms, selecting sensitive interventions, and monitoring intervention effectiveness for reduction of target symptoms (BLINDED FOR REVIEW). For example, if the symptoms have distinct antecedents or determinants, strategies used to foster symptom prevention or predict risk for symptom exacerbation would differ. In the clinical setting, nurses and other clinicians must identify symptoms and their relevant contributing factors. Communication across care teams must remain distinct in the description and discussion of related symptoms, as apathy and passivity may not be interchangeable. Lastly, existing evidence regarding best available treatments may have inadequate translatability to clinical practice if the measures used to identify symptoms and treatment responses are conceptually flawed or lack precision. Furthermore, clear delineation of clinical concepts, consistent measurement, and clear communication among scientists and clinicians regarding these symptoms is limited. Apathy and passivity are important clinical concepts in the care of people with dementia and represent commonly observed symptoms meriting nursing intervention. To clarify the intended targets of existing interventions and refine the development of future interventions, a stronger understanding of the conceptual and operational delineations between these two concepts is needed in order to strengthen the degree of symptom classification in future research, and consequentially translation to practice. This paper aims to address this gap by presenting results from a simultaneous concept analysis of apathy and passivity in dementia. The objective of this analysis of published literature was to clarify the concepts of apathy and passivity in the context of dementia by identifying distinguishing and overlapping attributes for both concepts simultaneously.

METHODS

Data Sources

A literature search focused on apathy and passivity in the context of dementia was conducted using the PubMed, CINAHL Plus, and PsycINFO databases. To identify relevant literature on apathy in dementia, the search terms “(dementia[MeSH] OR dementia OR Alzheimer*) AND (apathy[MeSH] OR apath*)” were used in PubMed. In the CINAHL Plus and PsychINFO databases, the search terms used were “apath* AND (dementia OR Alzheimer*).” A search for relevant literature on passivity in dementia was conducted using the same three databases. In PubMed, the search terms used were “(dementia[MeSH] OR dementia OR Alzheimer*) AND passiv*).” In the CINAHL Plus and PsycINFO databases, the search terms used were “passiv* AND (dementia OR Alzheimer*).” All searches were limited to English language and publication dates from 1980 to 2015.

Publications were screened using the following inclusion criteria in accordance with PRISMA guidelines: (1) published in peer-reviewed journals, (2) specific to the context of dementia, and (3) provided conceptual and/or operational definitions of apathy or passivity. Published articles were excluded if they (1) included apathy or passivity as a variable but failed to provide any definition or (2) were not related to dementia. Search results were screened separately by two reviewers, and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Concept Analysis Procedures

Authors applied a modified combination of Haase and colleagues’ (1993) simultaneous concept analysis method and Morses’ (1995) principle-based concept analysis using qualitative content and thematic analysis procedures to identify overlapping and distinguishing constructs. Haase and colleagues describe eight sequential steps for simultaneous concept analysis that emphasize an iterative process of examining interrelationships across concepts using a consensus group. Morse emphasizes the importance of aligning technical procedures in a concept analysis with the complexity and maturity of the concept, and the specific purpose of the analysis. While Haase and colleagues focus on identification of definitions, critical attributes, antecedents and outcomes, Morse suggests expanded structural features of attributes be integrated. Further, Morse suggests that data pertaining to each concept be kept separate until all relevant attributes are developed in the comparison stage of the analysis. In addition to the strategies outlined by Haase and colleagues (1993), authors incorporated qualitative and quantitative techniques to strengthen critical analysis at comparative stages of concept delineation in accordance with principle-based concept analysis procedures (Morse, 1995; Morse, Hupcey, Mitcham, & Lenz, 1996).

The goals of this project were to both characterize and attempt to delineate apathy and passivity, as there is ample published literature to draw from. A consensus group was formed (step 1) to carry out the eight-step simultaneous concept analysis procedures detailed by Haase and colleagues (1993). After selecting concepts to be analyzed (step 2), authors further refined these concepts (step 3) to incorporate the terminology “passive behaviors” into the passivity concept.

A standardized coding manual for characterizing descriptions of apathy and passivity was developed (step 4) using the following categories: conceptual definitions, operational definitions, concurrent conditions, functional/behavioral correlates, neurobiological attributes, neurobiological correlates, antecedents, and consequences (Table 1). After initial piloting of these categories to develop concept matrices (step 5), modifications to classification procedures in the developed coding manual were made in light of re-examination of data and consensus group dialogue that clarified the distinctions across each attribute (steps 6–7). These efforts resulted in the eventual development of a process model (step 8).

Table 1.

Critical Attribute Categories for Categorizing Definitions of Apathy and Passivity

| Critical Attribute Category | Critical Attribute Definition & Coding Guidance | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Definition | Description of concept containing defining characteristics or attributes to aid in determining which phenomena match the concept and which do not. Conceptual definitions contain more abstract descriptions of phenomena as opposed to objective descriptions or operationalization of these constructs. Conceptual definitions are further denoted when using the words “defined as,” “characterized as” or “described as.” | ▪ “Apathy has been defined as a lack of motivation leading to a reduction of self-generated voluntary and purposeful behaviors” ▪ “Passivity is defined as a personality pattern that is exemplified by a diminished ability to be open, conscious, and engaged” |

| Observable Clinical Features |

Descriptions of presence or absence of characteristics that aid in making differential diagnoses, or help name the occurrence of a specific phenomenon as differentiated from another similar or related one, as it occurs in a clinical setting. Observable clinical features are objective/observable indications or features of the conceptual definition. They are denoted when using the words “manifested by,” “characterized by,” “clinically manifested by,” “presents as,” “demonstrated by,” “items” and “behaviors.” | ▪ “Patients with apathy display lack of interest, anergia, psycho-motor slowing, and fatigue” ▪ “Passive behavior … characterizes the ‘silent majority’ of persons who manifest a reduction of energy, drive, and initiative” |

| Neurobiological Attribute | Characteristics that aid in making differential diagnoses, or help name the occurrence of a specific phenomenon as differentiated from another similar or related one, as it pertains to the nervous system of a patient. Only code neurobiological attributes that are descriptions of primary study findings. | ▪ “Apathy associated with pathology and reduction in function of the anterior cingulate cortex” |

| Antecedent | Events or incidents that must occur/be present or not occur/be present prior to the occurrence of a concept, such that description denotes a specific time frame. | ▪ “Apathy has been found to arise when there is pre-existing dysfunction in any GDB component in the brain” |

| Concurrent Condition | Descriptions of other clinical syndromes or diagnoses that are commonly present when the phenomena/concept of interest is present. These conditions may have significant influence on or determine the manifestation of the phenomena. | ▪ “Apathy is common in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease” ▪ “[Passive behaviors] as disturbing behaviors often observed in individuals with dementia” |

| Correlate | Descriptions of other factors (e.g. demographics, patient characteristics including neurobiological correlates – e.g. hypoperfusion in certain brain regions, clinical outcomes) that have been shown to have a relationship, association or correlation with the concept that but is not described as a causal relationship. General descriptions of neurobiological features that are associated with apathy may also be included. | ▪ “Apathy is associated with early institutionalization, increased morbidity, and mortality” ▪ “increased evidence of passivity in prodromal AD is related to the increasing cognitive decline that occurs during this period” |

| Consequence | Events or incidents that occur because of the occurrence of the concept of interest. Description denotes a temporal or causal relationship. |

▪ “Apathy has been shown to contribute uniquely to the loss of independence observed in AD” ▪ “Apathy has been shown to lead to functional decline” |

Categorization of Critical Attributes

During the execution of step 4, clarification of individual concepts, authors incorporated guidance from principal-based concept analysis (Penrod & Hupcey, 2005) and established an expanded classification of relevant critical attributes to strengthen the characterization of each concept in a way that could be thematically analyzed and tabulated. To facilitate this categorization, all distinct descriptions of the concepts of apathy and passivity available in the included articles were extracted verbatim, and these descriptions were then classified across relevant critical attribute categories using the developed manual. Accurate and consistent categorization of attributes was guided by a standardized coding manual, wherein positive and negative case examples were presented to guide decision-making (Table 1). For example, conceptual definitions were differentiated from operational definitions with key phrases such as “defined as” and “described as” versus “characterized by” and “clinically manifested by.” Antecedents, concurrent conditions, and consequences were distinguished from each other by determining the temporal relationship between attribute and symptom as presented in each article; however, the study team did not critically appraise the validity of the temporal relationships described in the published literature and limited the incorporation of temporal attributes in concept delineation. Neurobiological descriptors were separated into two distinct categories depending on whether the study was presenting primary findings or citing secondary sources. Throughout the process of categorizing the critical attributes of apathy and passivity, every individual textual description was permitted to contribute critical attributes in more than one category but never to the same category twice. All extracted text was categorized by two independent study team members, who performed memoing while coding to facilitate comparison and establishment of consensus related to the critical attributes.

Thematic Analysis of Critical Attributes

The eighth step in the simultaneous concept analysis procedure is the development of a process model, which focused on conceptual and operational attributes. Rather than being derived from the consensus group alone, authors applied systematic qualitative and quantitative procedures to the resultant critical attributes. Specifically, after achieving consensus in categorizing critical attributes, each was thematically analyzed to identify discrete constructs (smaller units of definition) (Braun & Clarke, 2006). To facilitate accurate determination of construct prevalence, each attribute was permitted to contribute to more than one discrete construct, but never to the same construct twice. Thematically-derived constructs from each critical attribute across all extracted descriptions of apathy and passivity were then tabulated quantitatively, consistent with quantitative content analysis procedures (Ryan & Bernard, 2000). Combined, these data resulted in both rich qualitative information about thematic features of critical attributes and objective information about the frequency of key attributes within and across each concept of interest. This thematic characterization of the text and tabulation of the discrete constructs facilitated the identification of overlapping and distinguishing features of apathy and passivity which allowed for a comparative process model (Haase et al, 1993).

RESULTS

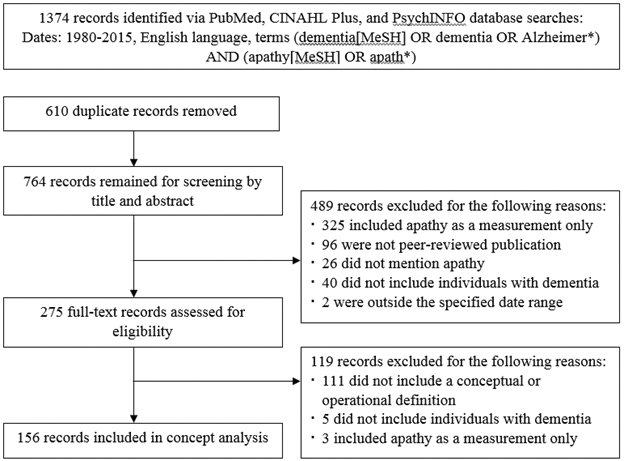

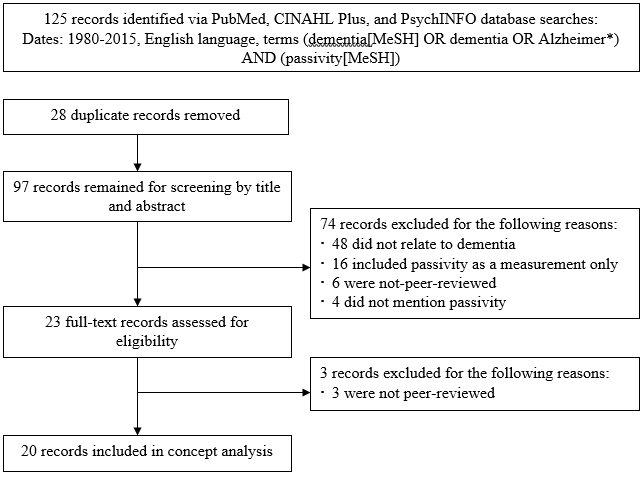

The literature search for apathy yielded 1374 records, with 156 articles identified as appropriate for inclusion in the simultaneous concept analysis (Figure 1). The passivity concept searches yielded fewer records, totaling 125 results across all databases. Twenty articles focused on the passivity concept were included in the simultaneous concept analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Flow Chart of Study Selection for Apathy

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Flow Chart of Study Selection for Passivity

Conceptual and Operational Attributes of Apathy and Passivity

In the selected articles, apathy was most commonly defined as a lack of motivation or a motivational disorder (n=133), decreased interest or concern (n=70), or a lack of self-initiated behavior aimed at a goal (n=53) (Table 2). The definitions were often associated with an inability to complete or persist in common daily activities of living. The symptom was described with the following operational or observable clinical features: lack of emotion, cognition, or behavior; emotional blunting; lack of interest; and reduced effort without negative self-appraisal, dysphoria, depression or loss of consciousness and cognition.

Table 2.

Common and Summarized Conceptual and Operational Definition Attributes of Apathy and Passivity

| Conceptual and Operational Definition Attributes† | Summarized Definition across Attributes | Example of Definition |

|---|---|---|

|

Apathy (N=156) Defined as: A lack of motivation or a motivational disorder (n=133) Decreased interest or concern (n=70) A lack of self-initiated behavior aimed at a goal (n=53) Loss of interest and motivation in daily activities (n=43) Absence or lack of feeling, emotion (n=33) A lack of concern/indifference (n=25) Can be observed/operationalized as: A lack of goal directed behavior, cognition or emotion (n=50) Emotional blunting (n=49) A lack of interest (n=43) A lack of/reduced initiative (n=39) Reduced effort or perseverance without negative self-appraisal (n=37) Diminished motivation (n=37) |

Apathy is defined as a lack of motivation, self-initiated and goal-directed behavior, and interest in daily activities. Its observable attributes include a decrease in behavior, cognition, emotion, interest and effort. Its definitions repeatedly distinguish it from a loss of consciousness, depression, and/or negative self-appraisal. |

“Apathy has been defined as a lack of motivation leading to a reduction of self-generated voluntary and purposeful behaviors” (Grossi et al., 2013). “This syndrome can be characterized as a disorder of motivation, clinically manifested by lack of initiative related to diminished goal-directed behavior, by reduction of interest associated with goal-directed cognition, and by emotional blunting which means lack or reduction of emotional responses” (Stella et al., 2014). |

|

Passivity (N=20) Defined as: A decrease in gross motor movement or psychomotor activity (n=12) Accompanied by apathy (n=7) Diminution of behavior (n=6) Lessening of emotions or response to emotions (n=5) A lack of interaction with the environment (n=5) A lack of interaction with people (n=4) Can be observed/operationalized as: Diminution of emotions, decreased response to emotions, emotional blunting (n=16) Decreased motor movements or psychomotor activity and decreased spontaneous and purposeful performance of voluntary motor movements (n=14) Diminution of interactions with the environment (n=11) Diminution of interactions with persons (n=9) Diminution of cognition/lessening mental process of thinking/knowing (n=7) Withdrawn/less responsive (n=6) |

Passivity is marked by a decrease in gross motor movement, and is often accompanied by apathy. Its observable attributes include a diminution of behavior, emotion, interaction with the environment and people, and cognition. |

“Passive behaviors are those associated with decreased motor movements, decreasing interactions with the environment, and feelings of apathy and listlessness” (Colling et al., 2000). “Overall, patients with passive disturbed behaviour were often difficult to reach, had lost interest in their environment, and showed few emotions” (de Vugt et al., 2003). |

The 6 most frequently mentioned attributes for conceptual and operational definitions of apathy and passivity were included in this table.

In contrast, passivity was defined as decreased psychomotor activity (n=12), a syndrome that is “accompanied by apathy” (n=7), a diminution of behavior (n=6) or emotion (n=5), or a lack of interaction with the environment (n=5) or with people (n=4). In the selected articles, passivity was operationalized as a diminution of emotions, lack of response to emotion or emotional blunting (n=16); decreases in motor movements, psychomotor movement, or purposeful movement (n=14); and a diminution of interaction with the environment (n=11) and persons (n=9). Passivity was described as encompassing a diminution of cognition or a lessening of mental processes (n=7).

Thematically-Derived Constructs across Conceptual Attributes

Across the 156 papers examined in relation to the apathy, 9 distinct and repeating conceptual constructs, or simple units of definition within the larger attributes. Across the 20 papers examined in relation to the passivity concept, 10 distinct and repeating conceptual constructs were found (See Table 3). For apathy, “Decreased motivation” was represented in 85.3% (n=133) of all definitions. In contrast, the construct of “Decreased psychomotor activity” was predominant in 60% (n=12) of all conceptual definitions for passivity, with remaining constructs ranging from 15–35% prevalence.

Table 3.

Number and Prevalence of Thematically-Derived Conceptual and Operational Constructs for Apathy and Passivity

| Apathy† (n=156) |

Passivity‡ (n=20) |

||

| Common Constructs across Conceptual Definition Attributes | |||

| Decreased motivation | 133 (85.3%) | - | |

| Decreased interest or concern | 70 (44.9%) | 3 (15.0%) | |

| Decreased initiative | 53 (34.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | |

| Decreased behavior | 42 (26.9%) | 6 (30.0%) | |

| Decreased emotion | 33 (21.2%) | 5 (25.0%) | |

| Decreased interaction with others | 17 (10.9%) | 4 (20.0%) | |

| Described as a syndrome | 12 (7.7%) | 4 (20.0%) | |

| Decreased interaction with environment | 10 (6.4%) | 5 (25.0%) | |

| Decreased awareness/ conscientiousness | 2 (1.3%) | 3 (15.0%) | |

| “Accompanied by apathy” | - | 7 (35.0%) | |

| Decreased psychomotor activity | - | 12 (60.0%) | |

| Common Constructs across Operational Definition Attributes | |||

| Decreased motivation | 74 (47.4%) | 2 (10.0%) | |

| Lack of goal-directed behavior, cognitive, emotion | 50 (32.1%) | - | |

| Emotional blunting | 49 (31.4%) | 16 (80.0%) | |

| Lack of interest | 43 (27.6%) | 5 (25.0%) | |

| Lack of initiative | 39 (25.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | |

| Decreased interaction with persons | 28 (17.9%) | 9 (45.0%) | |

| Diminution of thinking, auto-activation | 26 (16.7%) | 7 (35.0%) | |

| NOT characterized as depression, dysphoria, emotional distress | 18 (11.5%) | - | |

| NOT attributable to decreased consciousness, cognitive impairment | 19 (12.2%) | - | |

| Indifference | 19 (12.2%) | 2 (10.0%) | |

| Psychomotor changes/decreases | 7 (4.5%) | 14 (70.0%) | |

| Lack of responsiveness | 8 (5.1%) | 6 (30.0%) | |

| Apathy | - | 6 (30.0%) | |

| Lack of interaction with environment | - | 11 (55.0%) | |

| Lack of insight | 6 (3.8%) | - | |

| Inability to initiate self-care activities | 3 (1.9%) | - | |

| Fearful | - | 2 (10.0%) | |

| Inappropriate hilarity | - | 3 (15.0%) | |

| Insecure | - | 3 (15.0%) | |

| Hobbies relinquished | - | 3 (15.0%) | |

For apathy, the following colors were used to visualize ranges: light grey 1–9%, medium grey 10–19 %, medium-dark grey 20–35%, dark grey 35+ %.

For passivity, the color/ranges were as follows: light grey 1–14%, medium grey 15–24%, medium-dark grey 25–39%, dark grey 40+ %.

Apathy and passivity overlapped in units of definition as a “Decrease in behavior” (26.9% [n=42] and 30% [n=6], respectively) and as a “Decrease in emotion” (21.2% [n=33] and 25% [n=5]). While both apathy and passivity were described as syndromes, it was more common that definitions for passivity included this construct (20.0% [n=4] for passivity; 7.7% [n=12] for apathy).

Thematically-Derived Constructs Across Operational Attributes

Across the 156 papers examined in relation to the apathy, 15 distinct and repeating operational constructs were identified. Across the 20 papers examined in relation to the passivity concept, 15 constructs were identified, 9 of which overlapped with constructs for apathy (Table 3). Across all definitions, apathy was operationalized most commonly with the construct “Decreased motivation” (47.4%, n=74) followed closely by a variety of discrete constructs: “Lack of goal-directed behavior, cognitive, emotion” (32.1%, n=50), “Emotional blunting” (31.4%, n=49), “Lack of interest” (27.6%, n=43), “Lack of initiative” (25.0%, n=39), “Decreased interaction with persons” (17.9%, n=28), and “Diminution of thinking, auto-activation” (16.7%, n=26). In contrast, passivity was operationalized by “Emotional blunting” (80.0%, n=16) and “Psychomotor changes/decreases” (70.0%, n=14). The next most common operational constructs for passivity included “Lack of interaction with the environment” (55.0%, n=11) and “Decreased interaction with persons” (45.0%, n=9).

The operationalization of apathy and passivity overlapped in three regions: “Lack of interest” (27.6% [n= 43] and 25.0% [n=5], respectively), “Lack of initiative” (25.0% [n=39] and 20.0% [n=4], respectively), and “Indifference” (12.2% [n=19] and 10.0% [n=2], respectively). Only apathy was characterized by a “Lack of goal-directed behavior, cognitive, emotion”; “Lack of insight”; and an “Inability to initiate self-care activities”. Additionally, apathy was distinguished by its exclusion of depression, dysphoria, emotional distress and cognitive impairment. Passivity was distinguished by the aforementioned “Emotional blunting” (80.0%, n=16), “Psychomotor changes/decreases” (70.0%, n=14), and “Lack of interaction with the environment” (55.0%, n=11). The operationalization of passivity also included the unique constructs of “Hobbies relinquished’ (15.0%, n=3), “Insecure” (15.0%, n=3), “Inappropriate hilarity” (15.0%, n=3), and “Fearful” (10.0%, n=2). In 30% of definitions, passivity included the presence of apathy in its operationalization.

Antecedents, Concurrent Conditions, and Consequences

The literature examined in relation to the apathy concept often described damage to regions of the brain involved in planning or damage to the prefrontal cortex as precursors to the onset of apathy (Table 4). Dysfunction in the frontal subcortical brain circuits (n=3), dysfunction in medial frontal and anterior cingulate regions (n=2), and dysfunction of the basal ganglia (n=2) were cited as antecedents to apathy. In contrast, no antecedents were mentioned in the literature focused on the passivity concept. Alzheimer’s disease was described as the most commonly co-occurring condition with both apathy (n=28) and passivity (n=2) in the literature examined. In addition, though less commonly, the apathy literature referenced lesions in the frontal lobe (n=6) as a concurrent condition. The literature focused on apathy mentioned several consequences of apathy including impairment in activities of daily living or functioning (n=6), caregiver distress (n=2), poor outcomes (n=1), loss of independence (n=1), and Alzheimer’s disease (n=1). In contrast, the literature focused on the passivity concept listed only caregiver burden as a consequence (n=2).

Table 4.

Antecedents, Concurrent Conditions, and Consequences† of Apathy and Passivity in Dementia

| Antecedents Described in Literature | Concurrent Conditions Described in Literature | Consequences Described in Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Apathy | Apathy | Apathy |

| Damage of neuronal circuits involved in planning of actions to ongoing or forthcoming behaviors (n=5) Damage to prefrontal cortex (n=4) Brain damage (general) (n=3) Dysfunction in frontal subcortical brain circuits (n=3) Dysfunction in medial frontal and anterior cingulate regions (n=2) Dysfunction of the basal ganglia (n=2) Lack of responsiveness to either reward or negative feedback (n=1) Impairment in working memory (n=1) Impairment in executive functions (n=1) Neuropsychiatric illness (n=1) Alzheimer’s Disease (n=1) |

Alzheimer’s Disease (n=28) Lesions in the frontal lobe (n=6) Basal ganglia diseases such as Huntington’s disease or Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (n=2) Decreased dopaminergic neurotransmission (n=2) Brain damage (n=2) Depression (n=1) Mild cognitive impairment (n=1) Lesions to the anterior cingulate (n=1) Neurodegenerative diseases (n=1) Functional impairment (n=1) Impulsivity (n=1) |

Impairment in activities of daily living or functioning (n=6) Caregiver distress (n=2) Poor outcomes (n=1) Loss of independence (n=1) Alzheimer’s Disease (n=1) |

|

Passivity None listed |

Passivity Alzheimer’s Disease (n=2) Neurodegenerative disease (n=1) |

Passivity Caregiver burden (n=2) |

Validity of temporally-linked attributes not examined

Functional and Behavioral Correlates

The selected literature focused on the apathy often related the symptom to changes in function and behavior. Most commonly, the papers described associations with the following outcomes: poor executive function (n=9), worse or faster decline in cognitive impairment (n=6), elevated burden and stress for caregivers (n=6), decline in activities of daily living (n=6), a lack of insight (n=6), increased morbidity and mortality or decreased response to treatment (n=3), aberrant motor behavior (n=3), disinhibition (n=3), or disrupted emotional processing (n=3). Increased resource use, decreased quality of life, poor initiation, and early institutionalization were correlates each described a single time in the apathy literature. The passivity literature contained discussion of the following functional and behavioral correlates: functional decline (n=2), hallucinations (n=1), and aggression (n=1).

DISCUSSION

While there is a well-developed and conceptually rich body of literature describing the symptoms of apathy and passivity in the context of dementia, there is a notable disparity among available publications focused on each concept. Twenty publications were included for the analysis of passivity, and 156 articles were included for the analysis of apathy. While multiple international workgroups are dedicated to clarifying the meaning and measurement of apathy (Lanctôt et al., 2017), less research has focused on passivity, particularly in recent years.

In accordance with the available published literature, this concept analysis suggests that apathy is a more mature concept than passivity, with strong and consistent reference to a few key theoretical and seminal papers, most notably including work by Marin (1991), Landes, Sperry, Strauss, & Geldmacher (2001), Levy & Dubois (2006), Starkstein & Leentjens (2008), and Robert and colleagues (2009). Authors suggest that apathy is uniquely distinguished from passivity by the constructs of decreased motivation, decreased interest or concern, and decreased initiative. While apathy was more robustly defined than passivity in the examined literature, there was widespread inconsistency in the conceptualization of apathy across papers reviewed, despite the availability of expert consensus statements and diagnostic criteria. However, the relatively large number of published articles related to apathy allowed authors to systematically analyze the overlapping literature.

Apathy is also more robustly defined than passivity from an operational standpoint. In a recent quantitative systematic review of nonpharmacological interventions to reduce apathy among individuals with dementia, there was little consensus for the measurement of apathy, with 12 different questionnaires and various observational measures of apathy based on video recordings, used among the 16 included randomized controlled trials (BLINDED FOR REVIEW). BLINDED FOR REVIEW and colleagues (2016) noted the complex nature of apathy and called for additional efforts to clarify the defining features of apathy and those that distinguish apathy from other behavioral symptoms, which is addressed in this simultaneous concept analysis. Measurement variation and differences in the operationalization of apathy may also suggest an incomplete understanding of the etiology of apathy, which hinders thoughtful selection of interventions based on a specific understanding of the target symptom and underlying mechanisms.

While antecedents, concurrent conditions, and consequences were commonly discussed for apathy, there was minimal discussion of these aspects related to passivity in the reviewed literature. In particular, damage to specific regions of the brain were discussed as precursors to apathy onset. Structural and functional neuroimaging modalities may prove to be useful in future identification and objective measurement of apathy among individuals with dementia, as apathy is associated with degeneration in the anterior cingulate, regional hypometabolism (Gatchel et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2007), and regional hypoperfusion (Kang et al., 2012). Ongoing research continues to explore alternative avenues for more objective quantification and measurement of apathy including concurrent measurement of apathy and environmental stimulation using an observational rating scale (Jao, Algase, Specht, & Williams, 2016) and the incorporation of biomarker-based identification of individuals most at risk for apathy as an avenue for targeted intervention (Skogseth et al., 2008). The present analysis suggests that apathy is a multifaceted concept that incorporates motivation, initiation and reward mechanisms. It is unclear whether biomarker-based risk identification or objective measurement would adequately reflect each of these elements of the concept of apathy.

Despite significant overlap between the concepts of apathy and passivity, passivity is likely a distinct concept from apathy that would benefit from further delineation in both its conceptualization and in its operationalization through refined measurement. The potential concept clarification for passivity and for comparative analyses between the two concepts was limited by the discrepancy in number of available publications focused on each concept. Based on the published literature included in this analysis, passivity is defined with a range of varying constructs. Passivity appears to be best distinguished by a decrease in psychomotor activity and a decrease in interaction with the environment or with people. This is in contrast to the concept of apathy, which is distinguished by the unique constructs of decreased motivation, decreased interest or concern, and decreased initiative. To that end, passivity appears to be partially dependent on apathy for its conceptual construction.

Limitations to this review include potential omission of relevant evidence due to restriction to published English-language only articles and potential interpretation bias in classifying operational and conceptual attributes despite the use of duplicate independent review of articles. As with all reviews, the present concept analysis is limited by the quality of primary evidence, particularly with regard to findings related to antecedents and consequences of the apathy and passivity concepts. The majority of primary studies lacked sufficient longitudinal design to establish temporal relationships.

CONCLUSION & RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

This simultaneous concept analysis establishes key distinguishing features for the symptoms of apathy and passivity, necessary for improving consistency in identification criteria and measurement. Findings can inform the development of more rigorous criteria for measurement of apathy and similar NPS in dementia. Results further suggest that nurses seeking interventions in response to apathetic or passive behaviors exhibited by individuals with dementia should seek to select interventions based on the range of motivational or interactive deficits observed. Patients who have difficulty initiating a task or who do not appear to respond to common reward mechanisms are likely to suffer from apathy, which may merit both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions (Lanctôt et al., 2017). Conversely, patients that primarily appear withdrawn from others and the environment are likely exhibiting passivity, which research suggests is effectively reduced through individualized activity therapy (Kolanowski & Buettner, 2008). More precise conceptualization and measurement across studies is needed to ultimately support the development of a stronger evidence base for targeted therapies to combat both apathy and passivity.

WHAT DOES THIS PAPER CONTRIBUTE TO THE WIDER GLOBAL CLINICAL COMMUNITY?

Apathy and passivity are two important symptoms experienced by patients with dementia, however key distinguishing features between the two have not yet been established and hinder precise classification and measurement.

Clear delineation of the symptoms of apathy and passivity in dementia can improve symptom identification, measurement, and provide for tailored nursing interventions

Acknowledgements:

The authors would also like to acknowledge Lily Walljasper, Tori Charpentier and Haley Fuhr for assistance with the literature search and preparation of this manuscript. The authors have obtained written consent from all contributors who are not authors and are named in this section.

Funding Statement: Dr. Gilmore-Bykovskyi reports receiving support from the National Institute on Aging, the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, and the National Hartford Centers of Gerontological Nursing Excellence. Dr. Dykstra Goris reports receiving support from the Kenneth H. Campbell Foundation for Neurological Research.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Relevance to Clinical Practice:The identification of key distinguishing features of apathy and passivity in dementia is a critical first step in ensuring consistent measurement of each concept.

REFERENCES

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colling KB (2004). Caregiver interventions for passive behaviors in dementia: Links to the NDB model. Aging & Mental Health, 8(2), 117–125. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001649626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatchel JR, Donovan NJ, Locascio JJ, Becker JA, Rentz DM, Sperling RA,... Marshall GA, (2017). Regional 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Hypometabolism is Associated with Higher Apathy Scores Over Time in Early Alzheimer Disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(7), 683–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Kales HC, & Lyketsos CG (2012). Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association, 308(19), 2020–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.36918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BLINDED FOR REVIEW

- Haase J, Leidy N, Coward D, Penn P, & Britt T (1993). Simultaneous Concept Analysis: A Strategy for Developing Multiple Interrelated Concepts In Rogers E & Knalf K (Eds.), Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques and Applications. Orlando, FL: W. B. Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood DG, Barker WW, Ownby RL, & Duara R (2000). Relationship of behavioral and psychological symptoms to cognitive impairment and functional status in Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(5), 393–400. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao Y-L, Algase DL, Specht JK, & Williams K (2016). Developing the Person–Environment Apathy Rating for persons with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 20(8), 861–870. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1043618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JY, Lee JS, Kang H, Lee HW, Kim YK, Jeon HJ,... Lee DS,(2012). Regional cerebral blood flow abnormalities associated with apathy and depression in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 26(3), 217–224. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318231e5fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski A (1995). Disturbing behaviors in demented elders: a concept synthesis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 9(4), 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski A, & Buettner L (2008). Prescribing Activities that Engage Passive Residents. An Innovative Method. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 34(1), 13–19. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080101-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BLINDED FOR REVIEW

- Lanctôt KL, Agüera-Ortiz L, Brodaty H, Francis PT, Geda YE, Ismail Z,... Abraham EH (2017). Apathy associated with neurocognitive disorders: Recent progress and future directions. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 13(1), 84–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, & Geldmacher DS (2001). Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 49(12), 1700–1707. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, & Dubois B (2006). Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits. Cerebral Cortex, 16(7), 916–928. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG (2015). Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia: Overview and Measurement Challenges. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2(3), 155–156. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2015.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin RS (1991). Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 3(3), 243–254. doi: 10.1176/jnp.3.3.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GA, Monserratt L, Harwood D, Mandelkern M, Cummings JL, & Sultzer DL (2007). Positron emission tomography metabolic correlates of apathy in Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology, 64(7), 1015–1020. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.7.1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimo L, Powers C, Moore P, Vesely L, Avants B, Gee J,... Grossman M, (2009). Neuroanatomy of apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitve Disorders, 27(1), 96–104. doi: 10.1159/000194658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM (1995). Exploring the theoretical basis of nursing using advanced techniques of concept analysis. Advances in Nursing Science, 17(3), 31–46. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199503000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, Hupcey JE, Mitcham C, & Lenz ER (1996). Concept analysis in nursing research: a critical appraisal. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 10(3), 253–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J, & Hupcey JE (2005). Enhancing methodological clarity: principle-based concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 50(4), 403–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert P, Onyike CU, Leentjens AF, Dujardin K, Aalten P, Starkstein S,... Byrne J, (2009). Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. European Psychiatry, 24(2), 98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, & Bernard HR (2000). Data Management and Analysis Methods In Denzin N & Lincoln Y (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd Edition (pp. 769–802). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Skogseth R, Mulugeta E, Jones E, Ballard C, Rongve A, Nore S,... Aarsland D, (2008). Neuropsychiatric correlates of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 25(6), 559–563. doi: 10.1159/000137671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein SE, & Leentjens AF (2008). The nosological position of apathy in clinical practice. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 79(10), 1088–1092. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.136895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun SM, Murman DL, Long HL, Colenda CC, & von Eye A (2007). Predictive validity of neuropsychiatric subgroups on nursing home placement and survival in patients with Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(4), 314–327. doi: 10.1097/01.jgp.0000239263.52621.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linde RM, Matthews FE, Dening T, & Brayne C (2017). Patterns and persistence of behavioural and psychological symptoms in those with cognitive impairment: the importance of apathy. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(3), 306–315. doi: 10.1002/gps.4464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wancata J, Windhaber J, Krautgartner M, & Alexandrowicz R (2003). The consequences of non-cognitive symptoms of dementia in medical hospital departments. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 33(3), 257–271. doi: 10.2190/abxk-fmwg-98yp-d1cu [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, Sands L, Lindquist K, Dane K, & Covinsky KE (2002). Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(16), 2090–2097. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]