Abstract

We implemented a carbapenem-saving strategy in hemato-oncology patients from 2013, using an empirical combination of piperacillin-tazobactam and amikacin for high-risk hemato-oncology patients with febrile neutropenia, who remain hemodynamically unstable > 72 hours despite initial cefepime treatment. All-cause mortality was not different between the two periods (6.54 and 6.57 deaths per 1,000 person-day, P = 0.926). Group 2 carbapenem use significantly decreased after strategy implementation (78.43 vs. 67.43 monthly days of therapy, P = 0.018), while carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli did not show meaningful changes during the study period. Our carbapenem-saving strategy could effectively suppress carbapenem use without an increase of overall mortality.

Keywords: Carbapenem-Saving, Piperacillin-Tazobactam, Amikacin, Gram-Negative Bacilli, Resistance

Graphical Abstract

To reduce unnecessary antibiotic use and improve outcomes, development of facility-specific guidelines for fever and neutropenia in hemato-oncology patients is required.1 Our center, a 1,950-bed tertiary care hospital, used cefepime as an initial empirical antibiotic for hemato-oncology patients with febrile neutropenia according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 Empirical antibiotics were escalated to group 2 carbapenems (Gr2Cs) for high-risk patients who remain hemodynamically unstable despite initial treatment.2 However, this approach raised concerns about carbapenem overuse. From 2013, we implemented a carbapenem-saving strategy using an empirical combination of piperacillin-tazobactam and amikacin (PTZ/AMK) as a bridging regimen before using Gr2C. To evaluate the effects of this strategy, we reviewed antibiotic use, antimicrobial resistance, and overall mortality before and after strategy implementation.

Our strategy was based on in vitro data showing that PTZ/AMK combination covered 92.8% of extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates.3 Since aminoglycosides were rarely used in our hospital, amikacin susceptibility was also relatively well preserved in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter spp. We recommended empirical administration of PTZ/AMK to high-risk hemato-oncology patients with febrile neutropenia,2 who remain hemodynamically unstable > 72 hours despite initial cefepime treatment and had no identification of any pathogenic organisms. This strategy was recommended by consultation and resident education without compulsory protocol. Although the carbapenem-saving strategy was applied to patients with febrile neutropenia, its effect on the amount of prescribed antibiotics and resistant pathogen was evaluated in the overall hemato-oncology patients because of the following reasons: 1) antibiotic use during febrile neutropenia would affect patients' flora and influence antimicrobial resistance of the following infections after the recovery from neutropenia, and 2) because hemato-oncology patients are admitted almost exclusively in hemato-oncology wards, resistant pathogens could be shared between patients through environment.

The study period was from the second quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2015: since our hospital experienced an outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome and partially closed in the second quarter of 2015, we evaluated a two-year period before that quarter.4 The carbapenem-saving strategy was implemented from the first quarter of 2013.

We collected administrative, mortality, antibiotic prescription, and blood culture data for hemato-oncology patients. Hemato-oncology wards included four general wards, one reverse-isolation ward for bone-marrow transplantation, and one intensive care unit. Prescription data on AMK, PTZ, group 1 carbapenem (Gr1C; ertapenem), and Gr2C (imipenem/cilastatin, meropenem, and doripenem) were calculated as days of therapy per 1,000 person-days (DOTs/1,000 PDs). Blood isolates of Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., and Acinetobacter spp. were identified and resistance was calculated as resistance rates per 1,000 PD.

Blood cultures were taken from peripheral veins or central lines and were processed by the BacT/ALERT 3D system (bioMérieux Inc., Marcy l'Etoile, France). For species identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing, a VITEK II automated system (bioMérieux Inc.) was used, utilizing a standard identification card and the modified broth microdilution method. Minimum inhibitory concentration breakpoints and quality-control protocols were used according to the standards established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. PTZ susceptibility for Acinetobacter spp. was not reported.

Student's t-test was used for comparison of continuous variables. To evaluate associations between antibiotic prescription and resistance, the monthly antibiotic resistance rate was compared with average DOTs of the prior three months using a linear regression model. All P values were two-tailed and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. 2017-10-002-003). Informed consent was waived since only overall statistical data was used without review of medical records of individual patients.

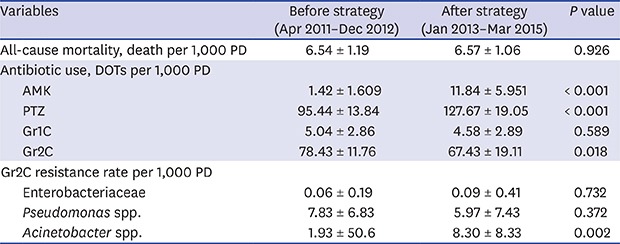

During the study period, a total of 34,258 patients were admitted to hemato-oncology wards. Average PD of monthly patients did not differ before and after strategy implementation (5,855.55 and 5,804.67; P = 0.294) (Table 1). All-cause mortality was not different between the two periods (6.54 and 6.57 deaths per 1,000 PD; P = 0.926). Monthly DOTs for AMK and PTZ significantly increased after strategy implementation (1.42 and 11.84 for AMK, P < 0.001; 95.44 and 127.67 for PTZ; P < 0.001). Increment of PTZ use far exceeded that of AMK: PTZ use increased for 32.23 monthly DOTs after strategy implementation, while AMK increased for 10.42 DOTs. Monthly DOTs for Gr2C significantly decreased after strategy implementation (78.43 and 67.43, P = 0.018). Gr1C use did not change. Incidence of gram-negative bacteremia did not significantly change. Enterobacteriaceae were most frequently isolated (6.64 average monthly cases per 1,000 PD), followed by Pseudomonas spp. (0.97) and Acinetobacter spp. (0.54). The overall trends of antibiotic resistance are presented in Fig. 1, and associations between antibiotic prescription and resistance are in Fig. 2.

Table 1. Comparison of before and after strategy implementation.

| Variables | Before strategy (Apr 2011–Dec 2012) | After strategy (Jan 2013–Mar 2015) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient, PD | 5,855.55 ± 130.30 | 5,804.67 ± 200.33 | 0.294 | ||

| All-cause mortality, death per 1,000 PD | 6.54 ± 1.19 | 6.57 ± 1.06 | 0.926 | ||

| Antibiotic use, DOTs per 1,000 PD | |||||

| AMK | 1.42 ± 1.609 | 11.84 ± 5.951 | < 0.001 | ||

| PTZ | 95.44 ± 13.84 | 127.67 ± 19.05 | < 0.001 | ||

| Gr1C | 5.04 ± 2.86 | 4.58 ± 2.89 | 0.589 | ||

| Gr2C | 78.43 ± 11.76 | 67.43 ± 19.11 | 0.018 | ||

| Bacteremia and resistance, per 1,000 PD | |||||

| Enterobacteriaceae | 5.99 ± 1.62 | 7.14 ± 2.58 | 0.067 | ||

| AMK resistance rate | 0.27 ± 0.51 | 0.27 ± 0.66 | 0.992 | ||

| PTZ resistance rate | 0.29 ± 0.52 | 1.42 ± 1.50 | 0.001 | ||

| Gr2C resistance rate | 0.06 ± 0.19 | 0.09 ± 0.41 | 0.732 | ||

| Pseudomonas spp. | 1.08 ± 0.97 | 0.88 ± 0.83 | 0.450 | ||

| AMK resistance rate | 1.42 ± 3.12 | 1.18 ± 3.73 | 0.806 | ||

| PTZ resistance rate | 5.08 ± 6.02 | 2.53 ± 5.44 | 0.137 | ||

| Gr2C resistance rate | 7.83 ± 6.83 | 5.97 ± 7.43 | 0.372 | ||

| Acinetobacter spp. | 0.21 ± 0.39 | 0.80 ± 1.37 | 0.043 | ||

| AMK resistance rate | 1.93 ± 5.06 | 2.80 ± 5.72 | 0.582 | ||

| Gr2C resistance rate | 1.93 ± 50.6 | 8.30 ± 8.33 | 0.002 | ||

Data are mean ± standard deviation.

PD = person-day, DOTs = days of therapy, AMK = amikacin, PTZ = piperacillin-tazobactam, Gr1C = group 1 carbapenem, Gr2C = group 2 carbapenem.

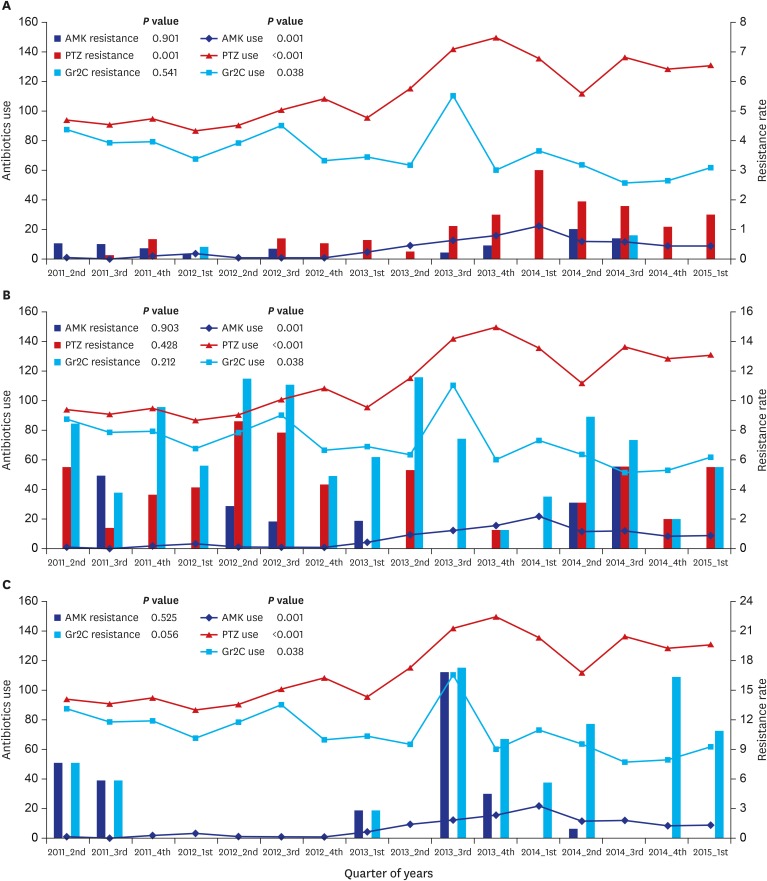

Fig. 1. Overall trend for antibiotic use and resistance.

Overall trend for antibiotic use and resistance in (A) Enterobacteriaceae, (B) Pseudomonas spp., and (C) Acinetobacter spp. Antibiotic use and resistance during the study period was evaluated by linear regression model and P values are in each figure. Antibiotic use is DOTs/1,000 PD, and resistance rate is percent per 1,000 PD.

AMK = amikacin, PTZ = piperacillin-tazobactam, Gr2C = group 2 carbapenem, DOTs = days of treatment, PD = person-day.

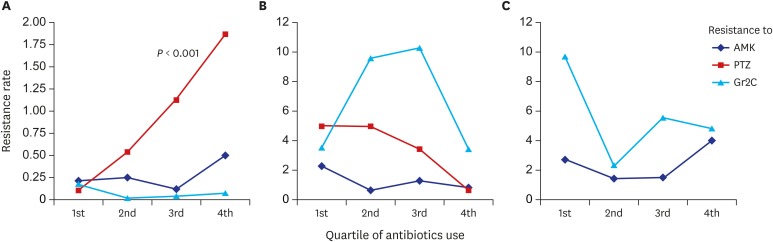

Fig. 2. Association between antibiotic prescriptions and resistance.

Association between antibiotic prescription and resistance for (A) Enterobacteriaceae, (B) Pseudomonas spp., and (C) Acinetobacter spp. evaluated by linear regression model with significant P values in figures. Resistant rate is percent per 1,000 PD.

AMK = amikacin, PTZ = piperacillin-tazobactam, Gr2C = group 2 carbapenem, PD = person-day.

Before strategy implementation, the antibiotic resistance rates of Enterobacteriaceae were, on average, 0.27% per 1,000 PD to AMK, 0.29% to PTZ, and 0.06% to Gr2C. Only PTZ resistance significantly increased after strategy implementation, to 1.42% per 1,000 PD (P = 0.001) (Table 1). AMK resistance did not increase during the study period despite an increase in AMK prescriptions (Fig. 1A), and no relationship between AMK prescription and resistance was observed (Fig. 2A). An increase in use of PTZ and increased PTZ resistance was seen during the study period (P = 0.001). A proportional increase in PTZ resistance according to PTZ prescriptions was observed (P = 0.006). Although carbapenem prescription was significantly decreased, significant reduction in carbapenem resistance was not observed. No relationship was seen between carbapenem prescription and resistance.

Antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas spp., on average, was 1.42% per 1,000 PD to AMK, 5.08% to PTZ, and 7.83% to Gr2C before strategy implementation. Resistance did not change after implementation (Table 1). The overall trend in antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas spp. is in Fig. 1B, and association between antibiotic prescription and resistance in Fig. 2B. No relationship was observed between antibiotic prescription and resistance.

Antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter spp., on average, was 1.93% per 1,000 PD to AMK and 1.93% to Gr2C before strategy implementation. The carbapenem resistance rate significantly increased to 8.30% after implementation (P = 0.002) (Table 1). The overall trend for antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter spp. is in Fig. 1C, and association between antibiotic prescription and resistance in Fig. 2C. Although carbapenem resistance increased after strategy implementation, it was not associated with prior prescription (P = 0.926).

In addition to systemic antibiotic stewardship programs using a computerized clinical decision support system,1,5 we emphasized non-compulsory methods through educational lectures, conferences, and consultation. This evaluation of a carbapenem-saving strategy represents the effect of these methods: increased AMK prescription after strategy implementation substituted that of Gr2C, and overall Gr2C use decreased significantly. All-cause mortality and Gr1C use did not change after strategy implementation. Good compliance to this non-compulsory strategy was owing to prescriber's understanding and concern about antibiotic resistance. However, increased PTZ prescription which was not directly related to the carbapenem-saving strategy, led to increased PTZ resistance of Enterobacteriaceae. Although we think the main deriving force of PTZ overuse would be increasing incidence of drug-resistant gram-negative pathogens and relatively preserved PTZ susceptibility,3,6,7,8 our carbapenem-saving strategy might contribute to PTZ overuse in other indications by weakening psychological barriers against PTZ prescription. This suggests that implementation of an antibiotic-using strategy should be accompanied by careful monitoring of overall antibiotic use.

The direct impact of decreased carbapenem prescription was limited to preventing an increase in carbapenem resistance. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae were rarely identified before strategy implementation, and carbapenem-resistant non-fermenters (Pseudomonas or Acinetobacter spp.) did not show meaningful changes during the study period. No relationship between antibiotic prescription and resistance was observed in non-fermenters, probably because we could not adjust for other resistance factors including environmental contamination or transmission from long-term care facilities.9,10,11 Also, since our data evaluated overall use of antibiotics and resistance rates, per-patient relationships between antibiotic use and resistance were not evaluated.

In conclusion, a carbapenem-saving strategy using PTZ/AMK as a bridging regimen in patients with febrile neutropenia effectively suppressed overall carbapenem use in hemato-oncology wards. This type of bridging regimen may be applied in other hospitals based on local epidemiology data along with overall antibiotic usage monitoring.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Ko JH, Kang CI.

- Data curation: Ko JH, Kim SH, Lee NY, Chung DR.

- Formal analysis: Kim SH.

- Investigation: Cho SY, Lee NY, Chung DR, Peck KR, Song JH.

- Writing - original draft: Ko JH.

- Writing - review & editing: Kang CI.

References

- 1.Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, MacDougall C, Schuetz AN, Septimus EJ, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51–e77. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, Boeckh MJ, Ito JI, Mullen CA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):e56–e93. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cha MK, Kang CI, Kim SH, Cho SY, Ha YE, Wi YM, et al. In vitro activities of 21 antimicrobial agents alone and in combination with aminoglycosides or fluoroquinolones against extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates causing bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(9):5834–5837. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01121-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park GE, Ko JH, Peck KR, Lee JY, Lee JY, Cho SY, et al. Control of an outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome in a tertiary hospital in Korea. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):87–93. doi: 10.7326/M15-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huh K, Chung DR, Park HJ, Kim MJ, Lee NY, Ha YE, et al. Impact of monitoring surgical prophylactic antibiotics and a computerized decision support system on antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(9):e145–e152. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang YT, Coombs G, Ling T, Balaji V, Rodrigues C, Mikamo H, et al. Epidemiology and trends in the antibiotic susceptibilities of gram-negative bacilli isolated from patients with intra-abdominal infections in the Asia-Pacific region, 2010–2013. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49(6):734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JJ, Seo YB, Lee J. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Enterobacteriaceae in community-acquired urinary tract infections during a 5-year period: a single hospital study in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2017;49(3):184–193. doi: 10.3947/ic.2017.49.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HS, Park BK, Kim SK, Han SB, Lee JW, Lee DG, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in febrile neutropenic children and adolescents with the impact of antibiotic resistance: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):500. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2597-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan DJ, Liang SY, Smith CL, Johnson JK, Harris AD, Furuno JP, et al. Frequent multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii contamination of gloves, gowns, and hands of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(7):716–721. doi: 10.1086/653201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falagas ME, Kopterides P. Risk factors for the isolation of multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2006;64(1):7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi WS, Kim SH, Jeon EG, Son MH, Yoon YK, Kim JY, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in intensive care units and successful outbreak control program. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(7):999–1004. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.7.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]