Abstract

Background

Even though cervico-vaginal smears have been used as a primary screening test for cervical carcinoma, the diagnostic accuracy has been controversial. The present study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of cytology for squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) and squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) of the uterine cervix through a diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) review.

Methods

A DTA review was performed using 38 eligible studies that showed concordance between cytology and histology. In the DTA review, sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic odds ratio (OR), and the area under the curve (AUC) on the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve were calculated.

Results

In the comparison between abnormal cytology and histology, the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 93.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 93.7%–94.1%) and 77.6% (95% CI, 77.4–77.8%), respectively. The diagnostic OR and AUC on the SROC curve were 8.90 (95% CI, 5.57–14.23) and 0.8148, respectively. High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) cytology had a higher sensitivity (97.6%; 95% CI, 94.7%–97.8%) for predicting HSIL or worse histology. In the comparison between SqCC identified on cytology and on histological analysis, the pooled sensitivity and specificity, diagnostic OR, and AUC were 92.7% (95% CI, 87.3%–96.3%), 87.5% (95% CI, 87.2%–87.8%), 865.81 (95% CI, 68.61–10,925.12), and 0.9855, respectively. Geographic locations with well-organized screening programs had higher sensitivity than areas with insufficient screening programs.

Conclusion

These results indicate that cytology had a higher sensitivity and specificity for detecting SIL and SqCC of the uterine cervix during primary screening.

Keywords: Cytology, Diagnostic Test Accuracy Review, Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Uterine Cervix

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

A cervico-vaginal smear, including the conventional smear and liquid-based cytology, is a simple and inexpensive test for the prediction of squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) or squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) of the uterine cervix.1 These tests have contributed to a decrease in the incidence of cervical cancer, especially in geographic areas supported by well-organized screening programs.1 Although several studies have reported on the diagnostic accuracy of the cervico-vaginal smear, results showed a wide range of estimated sensitivity compared to the specificity.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 Because the diagnostic accuracy can be affected by variable factors, including study time, geographic area, and population,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 it should be fully elucidated based on these standardized parameters, including the diagnostic grades of cytology. We tried to establish the universally acceptable value beyond the limitations of individual studies. A diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) review should be performed to confirm the cytology test outcomes of the uterine cervix.

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of cytology, the concordance rates between cytology and histology of the uterine cervix were investigated. In addition, the present study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of cytology for SIL and SqCC of the uterine cervix through DTA review. A subgroup analysis based on the number of patients and study location was also conducted.

METHODS

Published study search and selection criteria

Relevant articles were obtained by searching the PubMed databases through January 31, 2018. There was no time limit for the start. These databases were searched using the following key words: ‘(Uterine Cervical Neoplasms OR Uterine Cervical Dysplasia OR Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia OR ((cervix OR cervical OR cervico*) AND (cancer* OR carcinoma OR adenocarcinoma OR neoplas* OR dysplas* OR dyskaryos*)) OR (CIN OR CINII* OR CIN2* OR CINIII* OR CIN3*) AND (SIL OR HSIL OR H-SIL OR LSIL OR L-SIL OR ASCUS OR ASC-US).’ The titles and the abstracts of all searched articles were screened for exclusion. Review articles, including the previous meta-analysis, were also screened to obtain additional eligible studies. Search results were then reviewed and articles were included if the study investigated the uterine cervix and there was information regarding the concordance between cytology and histology. The articles were excluded when they were case reports or non-original articles or non-English language publications.

Data extraction

Data from all eligible studies1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 were extracted by two independent authors. Extracted data included the following: first author's name, year of publication, study location, dates of the research, methodology of cytologic examination, and number of patients analyzed. For the meta-analysis, we extracted all data associated with the concordance between cytology and histology in various categories of comparison.

Statistical analyses

The review of DTA was performed using the Meta-Disc program (version 1.4; Unit of Clinical Biostatics, the Ramon y Cajal Hospital, Madrid, Spain). In order to calculate the pooled sensitivity and specificity, individual data were collected from each eligible study in various categories of comparison. The summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve was initially constructed by plotting ‘sensitivity’ and ‘1-specificity’ of each study, and the curve fitting was performed through linear regression using the Littenberg and Moses linear model. Because the data were heterogeneous owing to differences in various methodology and populations, the accuracy data were pooled by fitting a SROC curve and measuring the value of the area under the curve (AUC). An AUC close to 1 indicates a strong test and an AUC close to 0.5 is considered as a poor test. In addition, the diagnostic odds ratio (OR) was calculated by the Meta-Disc program. The estimated values were those that predict abnormal histology of abnormal cytology. In addition, the estimated values of cytologic low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), and SqCC were predicted to histologic LSIL, HSIL or worse, and SqCC. To obtain the detailed information, a subgroup analysis based on number of patients, was conducted.

To obtain the results of concordance between abnormal cytology and histology, the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software package was used (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). The concordance was measured by agreement rates between HSIL identified with cytology and histology and between SqCC identified with cytology and histology. Because the eligible studies used various cytologic methods, including conventional and liquid-based preparations, in various populations, a random-effects model was more suitable than a fixed-effects model. Heterogeneity between the studies was checked using the Q and I2 statistics and presented using P values. To assess publication bias, Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test were used. The results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Selection and characteristics

A total of 3,314 reports were searched and screened in the database. Due to insufficient information on concordance, 3,155 reports were excluded. An additional 48 reports were excluded owing to results reported on other diseases, 45 were excluded because they were non-original, and 28 articles were excluded because they were written in non-English language. Finally, 38 studies were included in the present analysis (Fig. 1 and Table 1), which provided data on 302,148 patients. Information on the concordance between abnormal cytology and histology test results is shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of study search and selection methods.

Table 1. Main characteristics of the eligible studies.

| Study | Location | Duration | Method | No. | No. of patientsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | FN | TN | |||||

| Agorastos et al.2 | Greece | 2000–2001 | CC | 1,296 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 22 |

| Agorastos et al.3 | Greece | 2011–2013 | LBC | 3,993 | 62 | 18 | 63 | 45 |

| Alanbay et al.4 | Turkey | 2013–2015 | CC | 52 | 23 | 17 | 9 | 0 |

| Beerman et al.5 | Netherland | 1997–2002 | CC | 86,469 | 347 | 498 | 30 | 49,826 |

| Belinson et al.6 | China | ND | LBC | 8,497 | ||||

| Benedet et al.7 | Canada | 1986–2000 | CC | 84,244 | 44,847 | 15,561 | 628 | 1,163 |

| Bigras and de Marval8 | Switzerland | ND | LBC | 13,842 | 209 | 150 | 285 | 884 |

| Blumenthal et al.9 | Zimbabwe | 1995–1997 | CC | 2,199 | ||||

| Canda et al.10 | Turkey | 2005 | CC | 5,835 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 2006–2009 | LBC | 13 | 4 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Cárdenas-Turanzas et al.11 | USA/Canada | ND | CC | 963 | 30 | 47 | 104 | 782 |

| Castle et al.12 | USA | 2008–2009 | LBC | 7,823 | 482 | 1,704 | 539 | 5,098 |

| Chung et al.13 | Korea | 2004 | CC | 1,221 | 27 | 2 | 9 | 17 |

| LBC | 32 | 2 | 3 | 17 | ||||

| Chute et al.14 | USA | 2003 | CC | 530 | 155 | 133 | 11 | 231 |

| Cuzick et al.15 | UK | 1992–1994 | CC | 1,985 | 64 | 54 | 43 | 43 |

| Cuzick et al.16 | UK | ND | CC | 10,358 | 117 | 280 | 39 | 551 |

| Depuydt et al.17 | Belgium | 2005–2007 | LBC | 2,905 | 45 | 27 | 42 | 153 |

| Ferreccio et al.18 | Chile | ND | CC | 8,265 | ||||

| Guo et al.19 | USA | 2000–2001 | LBC | 788 | 551 | 63 | 65 | 103 |

| Hovland et al.20 | Congo | ND | CC | 301 | ||||

| LBC | ||||||||

| Hutchinson et al.21 | Costa Rica | ND | CC | 8,636 | 219 | 357 | 101 | 7,956 |

| LBC | 284 | 811 | 39 | 7,502 | ||||

| Iftner et al.22 | Germany | ND | LBC | 9,451 | ||||

| Kim et al.1 | Korea | 2005–2012 | LBC | 3,141 | 623 | 152 | 47 | 2,319 |

| Li et al.23 | China | 2004–2005 | LBC | 2,562 | ||||

| Mahmud et al.24 | Congo | 2003–2004 | CC | 1,366 | 16 | 33 | 24 | 441 |

| McAdam et al.25 | Vanuatu | 2006 | LBC | 519 | 38 | 13 | 13 | 6 |

| Monsonego et al.26 | France | 2008–2009 | LBC | 4,429 | 268 | 117 | 344 | 378 |

| Negri et al.27 | Italy | 2000–2002 | CC | 214 | 27 | 2 | 9 | 17 |

| LBC | 36 | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Pan et al.28 | China | ND | LBC | 1,780 | 174 | 339 | 39 | 1,441 |

| Parakevaidis et al.29 | Greece | 1997–1999 | CC | 977 | 64 | 179 | 11 | 34 |

| Petry et al.30 | Germany | 1998–2000 | CC | 8,466 | ||||

| Rahimi et al.31 | Italy | ND | CC | 461 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| LBC | 14 | 3 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Salmerón et al.32 | Mexico | 1999 | CC | 7,732 | 77 | 59 | 72 | 213 |

| Sankaranarayanan et al.33 | India | 1999–2003 | CC | 24,915 | 718 | 1,285 | 638 | 20,018 |

| Schneider et al.34 | Germany | 1996–1998 | CC | 5,455 | 24 | 2 | 140 | 193 |

| Sigurdsson35 | Iceland | 2007–2011 | CC | 61,574 | 1,603 | 206 | 24 | 18 |

| LBC | 1,081 | 111 | 7 | 57 | ||||

| Sykes et al.36 | New Zealand | 2004–2006 | CC | 913 | 250 | 60 | 16 | 35 |

| LBC | 253 | 59 | 23 | 41 | ||||

| Wu et al.37 | China | ND | LBC | 2,098 | ||||

| Zhu et al.38 | Sweden | ND | CC | 137 | 84 | 25 | 23 | 5 |

| LBC | 89 | 23 | 18 | 7 | ||||

TP = true positive, FP = false positive, FN = false negative, TN = true negative, CC = conventional cytology, LBC = liquid-based cytology, ND = no description.

aConcordance between abnormal cytology and abnormal histology.

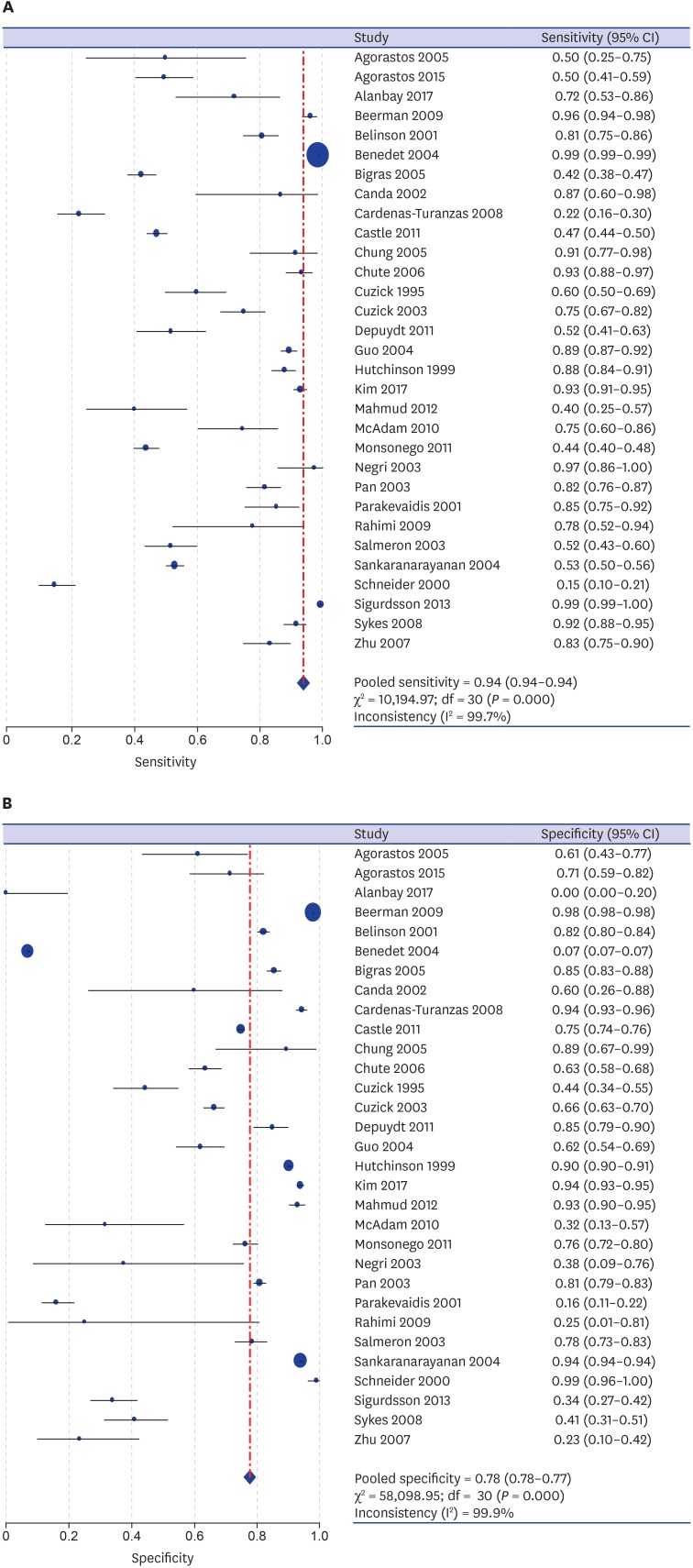

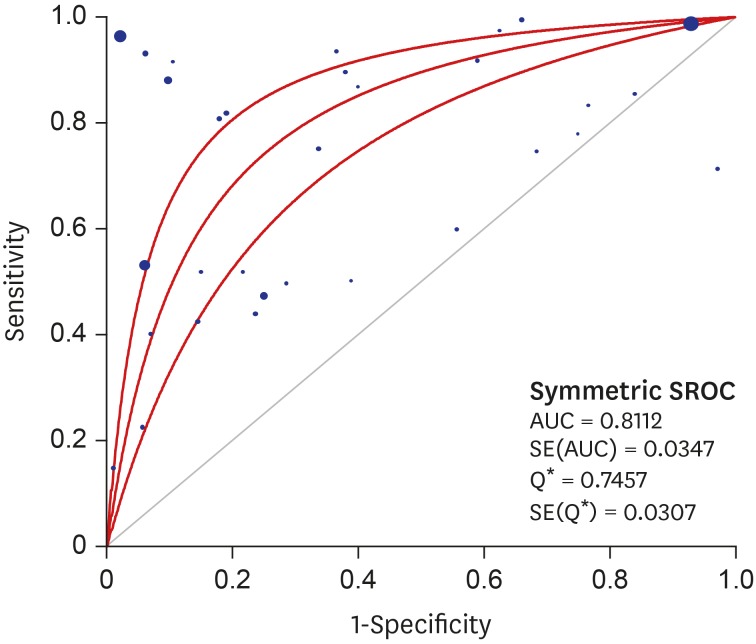

DTA review of cytology

A DTA review was conducted to elucidate the diagnostic accuracy using cytology in uterine cervix. In the comparison between abnormal cytology and histology, the pooled sensitivity and specificity values were 93.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 93.7%–94.1%) and 77.6% (95% CI, 77.4%–77.8%), respectively (Fig. 2). The diagnostic OR and AUC on the SROC curve were 8.90 (95% CI, 5.57–14.23) and 0.8112, respectively (Fig. 3). A subgroup analysis based on the number of included patients of each eligible study (≥ 1,000 and < 1,000) and study locations (areas with well-organized versus insufficient screening programs) was conducted. In the subgroup that included the larger number of patients, the pooled sensitivity and specificity, diagnostic OR and AUC on the SROC curve were 94.9% (95% CI, 94.8%–95.1%), 77.8% (95% CI, 77.5%–78.0%), 22.91 (95% CI, 10.70–49.04), and 0.8963, respectively. However, the pooled sensitivity and specificity of the subgroup with a smaller number of patients was 71.1% (95% CI, 69.3%–72.9%) and 73.6% (95% CI, 72.2%–75.0%), respectively. Next, in the subgroup analysis based on study location, areas with well-organized screening programs had a higher sensitivity than areas with insufficient screening programs (94.9% vs. 71.1%).

Fig. 2. The forest plots for the sensitivity and specificity of abnormal cytology in predicting SIL or SqCC in uterine cervix. (A) Sensitivity. (B) Specificity.

SIL = squamous intraepithelial lesion, SqCC = squamous cell carcinoma, CI = confidence interval.

Fig. 3. SROC curve of abnormal cytology in predicting SIL or SqCC in uterine cervix.

SROC = summary receiver operating characteristic, SIL = squamous intraepithelial lesion, SqCC = squamous cell carcinoma, AUC = area under the curve, SE = standard error, Q* = the point where sensitivity and specificity are equal.

In the comparison between LSIL identified with cytology and LSIL identified with histology, the pooled sensitivity and specificity, diagnostic OR, and AUC were 80.5% (95% CI, 78.7%–81.2%), 80.6% (95% CI, 80.2%–81.0%), 11.80 (95% CI, 5.30–26.29), and 0.8339, respectively (Table 2). For predicting HSIL or worse histology, the sensitivity and specificity of LSIL cytology were 97.6% (95% CI, 97.4%–97.8%) and 71.7% (95% CI, 71.3%–72.0%), respectively. The diagnostic OR and AUC were 64.49 (95% CI, 29.04–143.20) and 0.9444, respectively. The pooled sensitivity and specificity, diagnostic OR, and AUC of cytologic SqCC were 92.7% (95% CI, 87.3%–96.3%), 87.5% (95% CI, 87.2%–87.8%), 865.81 (95% CI, 68.61–10,925.12), and 0.9855 for predicting SqCC in histology. In the subgroup analysis, those that used conventional cytology and well-organized screening programs had a higher sensitivity and lower specificity than subgroups that used liquid-based cytology and lacked screening programs.

Table 2. Sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic OR and AUC of SROC curve in cases with histologic confirmation.

| Comparison | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | Diagnostic OR (95% CI) | AUC on SROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSIL in cytology vs. LSIL in histology | 80.5 (78.7–81.2) | 80.6 (80.2–81.0) | 11.80 (5.30–26.29) | 0.8339 |

| HSIL in cytology vs. HSIL+ in histology | 97.6 (97.4–97.8) | 71.7 (71.3–72.0) | 64.49 (29.04–143.20) | 0.9444 |

| SqCC in cytology vs. SqCC in histology | 92.7 (87.3–96.3) | 87.5 (87.2–87.8) | 865.81 (68.61–10,925.12) | 0.9855 |

OR = odds ratio, AUC = area under curve, SROC = summary receiver operating characteristic, CI = confidence interval, LSIL = low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL = high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL+ = HSIL or worse, SqCC = squamous cell carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

In daily practice, screening tests use cytology and/or the human papillomavirus (HPV) test to predict SIL and SqCC of the uterine cervix. However, it is difficult to obtain information on diagnostic accuracy of cytology and the HPV test from individual studies. Previous studies show that the ranges of sensitivities and specificities of cytology and HPV test varied widely.39 In the eligible studies, sensitivities and specificities of cytology ranged from 22.4% to 99.4% and 0.0% to 99.0%, respectively.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 Therefore, it is useful to assess the diagnostic accuracy of a screening test to predict the presence of SIL and SqCC in the uterine cervix by performing a meta-analysis, including a DTA review. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to assess the diagnostic accuracy of cytology for predicting SIL and SqCC in the uterine cervix.

In the present DTA review, regardless of the diagnostic grade of cytology, its diagnostic accuracy was initially evaluated for the prediction of abnormal histology. The sensitivity and specificity of cytology were 93.9% and 77.6%, respectively. In a subgroup analysis based on the number of patients, the larger subgroup showed a higher sensitivity than the smaller subgroup (94.9% vs. 71.1%). Eligible studies with a small number of patients might affect the sensitivity and specificity, since patient cohort sizes ranged from 13 to 50,701. In addition, experiences of cytopathologists and cytotechnologists may be important for the diagnostic accuracy of cytologic examination. Recent automated cytoscreening systems can also be helpful for effective screening. Results of this DTA review show that cytology is a useful screening test in the prediction of SIL or SqCC histology.

In the DTA review for the diagnostic accuracy of cytology, index should be cytology and comparator test should be histology. However, in previous studies, colposcopy was included in the comparator test.39 Cases with negative colposcopic findings were considered as true negative in these studies.39 However, because colposcopy is not a confirmative examination, specificity might be overestimated due to the increase in true negative cases. Therefore, cytology and histology should be compared to properly evaluate the diagnostic accuracy. The present study included only patients with histologic confirmation, but not those who underwent colposcopic examination.

In a previous DTA review, the sensitivity of cytology and HPV test were 65.87%–75.51% and 92.60%–95.13%, respectively.39 However, in this study, cytology was compared between atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) or worse cytology and HSIL histology. The true positive rate and sensitivity were decreased because patients who underwent LSIL histology were considered false positives in abnormal cytology. The sensitivity of cytology was higher in our study compared to the previous DTA review. Therefore, overestimation of specificity could be possibly considered. In addition, the previous DTA review only included studies that assessed both cytology and HPV tests. The estimated value for diagnostic OR and AUC on SROC, which are useful in comparing various tests, were not shown. In summary, the superiority of the HPV test for accurately diagnosing SIL or SqCC in the uterine cervix cannot be proven in the previous DTA review. In addition, in other DTA review,40 the pooled sensitivity of cytology with HSIL or worse was 79.4% for predicting cancer. However, this review did not show results for other parameters, such as specificity, diagnostic OR, AUC on SROC. The estimated values of overall abnormal cytology and LSIL were not found in the previous review.40

In practice, ASC-US cytology usually requires a repeat smear and/or an HPV test. An ancillary test, such as the HPV test, may be useful because the confirmative information in the repeat smear cannot be obtained. However, the gradient correlation between HPV test and histology is unclear. The advantage of cytology is its ability to predict histologic abnormalities which can help with patient management, compared to that of an HPV test. After a cytologic preparation, HPV tests using the remaining cytologic specimen can be performed. The presence of ASC-US cytology groups, which can increase the false-positive rate and decrease sensitivity. In the previous study, the rate of ASC-US cytology was less than 5.0%.12 However, in the Republic of Korea which has a well-organized screening system, the rate of ASC-US were 0.045% in 432,691 women who had screening tests.1 Therefore, an ancillary HPV test can be more useful in patients with ASC-US cytology. In areas with insufficient screening systems, the effectiveness of a cytologic examination is not fully elucidated. In addition, in areas with a well-organized screening system, the usefulness of an HPV test as the primary screening test is unclear. Primary screening tests should not be selected by simply considering the sensitivity. Availability of screening systems may be important for choosing the screening method to help diagnose SIL or SqCC of the uterine cervix.

In a subanalysis of the ATHENA study, co-testing using cytology and the HPV test has no advantage compared with the HPV test alone.12 However, this study did not enroll patients without an HPV test. This criterion could decrease the sensitivity and true positive cases of cytology. In addition, this report compared ASC-US and worse cytology with HSIL or worse confirmed with histology. Therefore, because sensitivity can differ by patient populations, the diagnostic accuracy of the screening test in the general population can differ between individual studies. The results showed that sensitivity of cytology in our results (96.9%) was higher than that of the HPV test sensitivity for HSIL or worse with histology as shown in Castle's report (88.2%). In addition, in our study, the estimated concordance rates were 93.1% (95% CI, 84.7%–97.1%) and 98.8% (95% CI, 69.0%–100.0%) for HSIL and SqCC cytology, respectively.

There are some limitations in the current DTA review. First, the comparisons between various cytologic abnormalities and histologic abnormalities were conducted in the present DTA review. ASC-US/atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H) cytology belongs to the heterogeneous diagnostic category. However, the diagnostic accuracy of ASC-H could not be performed due to insufficient information included in the eligible studies. Second, the aim of the present DTA review was to elucidate the diagnostic accuracy of cytology. Thus, the effectiveness between cytology and HPV test was compared with the results of previous reports.12,39 Third, the number of patients in the individual studies did not apply to exclusion criteria in the present DTA review. The eligible studies with a smaller number of patients showed far from average estimation. However, the effects of studies with a smaller number of patients on overall estimated values were insignificant. Therefore, the diagnostic accuracy of cytology using individual studies with a smaller number of patients should be accurately interpreted. Fourth, histologic examinations include a punch biopsy, loop electrocautery excision procedure, conization, or hysterectomy in the uterine cervix. Sampling error can occur with histologic examinations, such as a punch biopsy. However, in the present DTA review, a detailed evaluation based on histologic methodology could not be conducted due to insufficient information on eligible studies.

In conclusion, our results show that cytology has higher sensitivity and specificity for the prediction of SIL or SqCC, regardless of the diagnostic grade of cytology. The diagnostic accuracy of cytology as a primary screening test was re-confirmed in the present DTA review. Therefore, cytology is one of the most sensitive and confirmative primary screening tests for SIL and SqCC.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a research grant received from the Korean Society of Cytopathology in 2018.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Pyo JS, Kang G.

- Data curation: Pyo JS, Yoon HK.

- Formal analysis: Pyo JS, Kang G.

- Investigation: Pyo JS, Kim HJ.

- Methodology: Pyo JS, Kang G.

- Writing - original draft: Pyo JS.

- Writing - review & editing: Pyo JS, Yoon HK, Kim HJ.

References

- 1.Kim SH, Lee JM, Yun HG, Park US, Hwang SU, Pyo JS, et al. Overall accuracy of cervical cytology and clinicopathological significance of LSIL cells in ASC-H cytology. Cytopathology. 2017;28(1):16–23. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agorastos T, Dinas K, Lloveras B, de Sanjose S, Kornegay JR, Bonti H, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for primary screening in women at low risk of developing cervical cancer. The Greek experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96(3):714–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agorastos T, Chatzistamatiou K, Katsamagkas T, Koliopoulos G, Daponte A, Constantinidis T, et al. Primary screening for cervical cancer based on high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) detection and HPV 16 and HPV 18 genotyping, in comparison to cytology. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alanbay İ, Öztürk M, Fıratlıgil FB, Karaşahin KE, Yenen MC, Bodur S. Cytohistological discrepancies of cervico-vaginal smears and HPV status. Ginekol Pol. 2017;88(5):235–238. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2017.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beerman H, van Dorst EB, Kuenen-Boumeester V, Hogendoorn PC. Superior performance of liquid-based versus conventional cytology in a population-based cervical cancer screening program. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):572–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belinson JL, Qiao YL, Pretorius RG, Zhang WH, Rong SD, Huang MN, et al. Shanxi Province cervical cancer screening study II: self-sampling for high-risk human papillomavirus compared to direct sampling for human papillomavirus and liquid based cervical cytology. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13(6):819–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2003.13611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benedet JL, Matisic JP, Bertrand MA. An analysis of 84244 patients from the British Columbia cytology-colposcopy program. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92(1):127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bigras G, de Marval F. The probability for a Pap test to be abnormal is directly proportional to HPV viral load: results from a Swiss study comparing HPV testing and liquid-based cytology to detect cervical cancer precursors in 13,842 women. Br J Cancer. 2005;93(5):575–581. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumenthal PD, Gaffikin L, Chirenje ZM, McGrath J, Womack S, Shah K. Adjunctive testing for cervical cancer in low resource settings with visual inspection, HPV, and the Pap smear. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;72(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canda MT, Demir N, Sezer O, Doganay L, Ortac R. Clinical results of the liquid-based cervical cytology tool, Liqui-PREP, in comparison with conventional smears for detection of squamous cell abnormalities. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10(3):399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cárdenas-Turanzas M, Nogueras-Gonzalez GM, Scheurer ME, Adler-Storthz K, Benedet JL, Beck JR, et al. The performance of human papillomavirus high-risk DNA testing in the screening and diagnostic settings. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(10):2865–2871. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castle PE, Stoler MH, Wright TC, Jr, Sharma A, Wright TL, Behrens CM. Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older: a subanalysis of the ATHENA study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):880–890. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung JH, Park EJ, Choi YD, Kim HS, Lee YJ, Ko HM, et al. Efficacy assessment of CellSlide in liquid-based gynecologic cytology. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99(3):597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chute DJ, Covell J, Pambuccian SE, Stelow EB. Cytologic-histologic correlation of screening and diagnostic Papanicolaou tests. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34(7):503–506. doi: 10.1002/dc.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuzick J, Szarewski A, Terry G, Ho L, Hanby A, Maddox P, et al. Human papillomavirus testing in primary cervical screening. Lancet. 1995;345(8964):1533–1536. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuzick J, Szarewski A, Cubie H, Hulman G, Kitchener H, Luesley D, et al. Management of women who test positive for high-risk types of human papillomavirus: the HART study. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1871–1876. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14955-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Depuydt CE, Makar AP, Ruymbeke MJ, Benoy IH, Vereecken AJ, Bogers JJ. BD-ProExC as adjunct molecular marker for improved detection of CIN2+ after HPV primary screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(4):628–637. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreccio C, Barriga MI, Lagos M, Ibáñez C, Poggi H, González F, et al. Screening trial of human papillomavirus for early detection of cervical cancer in Santiago, Chile. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(4):916–923. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo M, Hu L, Baliga M, He Z, Hughson MD. The predictive value of p16(INK4a) and hybrid capture 2 human papillomavirus testing for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122(6):894–901. doi: 10.1309/0DGG-QBDQ-AMJC-JBXB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovland S, Arbyn M, Lie AK, Ryd W, Borge B, Berle EJ, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of the accuracy of cervical pre-cancer detection methods in a high-risk area in East Congo. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(6):957–965. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutchinson ML, Zahniser DJ, Sherman ME, Herrero R, Alfaro M, Bratti MC, et al. Utility of liquid-based cytology for cervical carcinoma screening: results of a population-based study conducted in a region of Costa Rica with a high incidence of cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;87(2):48–55. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990425)87:2<48::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iftner T, Becker S, Neis KJ, Castanon A, Iftner A, Holz B, et al. Head-to-head comparison of the RNA-based aptima human papillomavirus (HPV) assay and the DNA-based hybrid capture 2 HPV test in a routine screening population of women Aged 30 to 60 years in Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(8):2509–2516. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01013-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li N, Shi JF, Franceschi S, Zhang WH, Dai M, Liu B, et al. Different cervical cancer screening approaches in a Chinese multicentre study. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(3):532–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahmud SM, Sangwa-Lugoma G, Nasr SH, Kayembe PK, Tozin RR, Drouin P, et al. Comparison of human papillomavirus testing and cytology for cervical cancer screening in a primary health care setting in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(2):286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAdam M, Sakita J, Tarivonda L, Pang J, Frazer IH. Evaluation of a cervical cancer screening program based on HPV testing and LLETZ excision in a low resource setting. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monsonego J, Hudgens MG, Zerat L, Zerat JC, Syrjänen K, Halfon P, et al. Evaluation of oncogenic human papillomavirus RNA and DNA tests with liquid-based cytology in primary cervical cancer screening: the FASE study. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(3):691–701. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negri G, Menia E, Egarter-Vigl E, Vittadello F, Mian C. ThinPrep versus conventional Papanicolaou smear in the cytologic follow-up of women with equivocal cervical smears. Cancer. 2003;99(6):342–345. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan Q, Belinson JL, Li L, Pretorius RG, Qiao YL, Zhang WH, et al. A thin-layer, liquid-based pap test for mass screening in an area of China with a high incidence of cervical carcinoma. A cross-sectional, comparative study. Acta Cytol. 2003;47(1):45–50. doi: 10.1159/000326474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paraskevaidis E, Malamou-Mitsi V, Koliopoulos G, Pappa L, Lolis E, Georgiou I, et al. Expanded cytological referral criteria for colposcopy in cervical screening: comparison with human papillomavirus testing. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82(2):355–359. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petry KU, Menton S, Menton M, van Loenen-Frosch F, de Carvalho Gomes H, Holz B, et al. Inclusion of HPV testing in routine cervical cancer screening for women above 29 years in Germany: results for 8466 patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(10):1570–1577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahimi S, Carnovale-Scalzo C, Marani C, Renzi C, Malvasi A, Votano S. Comparison of conventional Papanicolaou smears and fluid-based, thin-layer cytology with colposcopic biopsy control in central Italy: a consecutive sampling study of 461 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37(1):1–3. doi: 10.1002/dc.20947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salmerón J, Lazcano-Ponce E, Lorincz A, Hernández M, Hernández P, Leyva A, et al. Comparison of HPV-based assays with Papanicolaou smears for cervical cancer screening in Morelos State, Mexico. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14(6):505–512. doi: 10.1023/a:1024806707399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sankaranarayanan R, Chatterji R, Shastri SS, Wesley RS, Basu P, Mahe C, et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening of cervical neoplasia: results from a multicenter study in India. Int J Cancer. 2004;112(2):341–347. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider A, Hoyer H, Lotz B, Leistritza S, Kühne-Heid R, Nindl I, et al. Screening for high-grade cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia and cancer by testing for high-risk HPV, routine cytology or colposcopy. Int J Cancer. 2000;89(6):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigurdsson K. Is a liquid-based cytology more sensitive than a conventional Pap smear? Cytopathology. 2013;24(4):254–263. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sykes PH, Harker DY, Miller A, Whitehead M, Neal H, Wells JE, et al. A randomised comparison of SurePath liquid-based cytology and conventional smear cytology in a colposcopy clinic setting. BJOG. 2008;115(11):1375–1381. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu R, Belinson SE, Du H, Na W, Qu X, Wu R, et al. Human papillomavirus messenger RNA assay for cervical cancer screening: the Shenzhen Cervical Cancer Screening Trial I. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(8):1411–1414. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181f29547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu J, Norman I, Elfgren K, Gaberi V, Hagmar B, Hjerpe A, et al. A comparison of liquid-based cytology and Pap smear as a screening method for cervical cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;18(1):157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koliopoulos G, Nyaga VN, Santesso N, Bryant A, Martin-Hirsch PP, Mustafa RA, et al. Cytology versus HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in the general population. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD008587. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008587.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castanon A, Landy R, Michalopoulos D, Bhudia R, Leaver H, Qiao YL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data to assess the sensitivity of cervical cytology for diagnosis of cervical cancer in low- and middle-income countries. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(5):524–538. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.008011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]