Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex surgical procedure with a high morbidity rate. The serious complications are major risk factors for poor long-term surgical outcome. Studies have reported an association between early postoperative prognostic nutritional index (PNI) and prediction of severe complications after abdominal surgery. However, there have been no studies on the use of early postoperative PNI for predicting serious complications following PD.

AIM

To analyze the risk factors and early postoperative PNI for predicting severe complications following PD.

METHODS

We retrospectively analyzed 238 patients who underwent PD at our hospital between January 2007 and December 2017. The postoperative complications were classified according to the Dindo-Clavien classification. Grade III-V postoperative complications were classified as serious. The risk factors for serious complications were analyzed by univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS

Overall complications were detected in 157 of 238 patients (65.9%) who underwent PD. The grade III-V complication rate was 26.47% (63/238 patients). The mortality rate was 3.7% (9/238 patients). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that preoperative serum albumin [odds ratio (OR): 0.883, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.80-0.96; P < 0.01] and PNI on postoperative day 3 < 40.5 (OR: 2.77, 95%CI: 1.21-6.38, P < 0.05) were independent factors associated with grade III-V postoperative complications.

CONCLUSION

Perioperative albumin is an important factor associated with serious complications following PD. Low early postoperative PNI (< 40.5) is a predictor for serious complications.

Keywords: Postoperative complications, Pancreatectomy, Serum albumin, Risk factors, Prognostic nutritional index

Core tip: Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex surgical procedure with a high morbidity rate. The serious complications are major risk factors for poor long-term surgical outcome. Studies have reported an association between early postoperative prognostic nutritional index (PNI) and prediction of severe complications after abdominal surgery. However, there have been no studies on the use of early postoperative PNI for predicting serious complications following PD. We retrospectively analyzed 238 patients who underwent PD at our hospital. The independent factors associated with serious postoperative complications following PD were preoperative serum albumin and PNI on postoperative day 3 of < 40.5. Thus, patients who undergo PD and have early postoperative low PNI should be monitored closely.

INTRODUCTION

The standard treatment for periampullary tumor is pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD)[1]. PD is a complex surgical procedure with a high morbidity rate of up to 50%[2-4]. However, the majority of complications are minor or grade I/II according to the Clavien-Dindo classification and do not affect long-term postoperative outcomes in patients with periampullary tumor[3-6]. Serious complications, Clavien-Dindo grade III-V, are major risk factors for poor long-term surgical outcome[2,7]. These complications increase length of hospital stay, reoperation and readmission, delay adjuvant treatment, and lead to mortality[8,9].

Several studies have investigated the use of inflammatory markers for prediction of severe postoperative complications following PD[10-13]. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) is a common inflammatory marker previously reported to be associated with postoperative outcomes[14-16]. PNI is a simple inexpensive marker that is calculated from serum albumin and total lymphocyte count[17]. Kanda et al[13] and Kim et al[18] have reported that preoperative nutritional status affects postoperative outcomes following pancreatic surgery. Sato et al[19] have reported that the rapid change in PNI following distal pancreatectomy is significantly associated with postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF). However, that study used PNI on postoperative day (POD) 7, which seemed to delay prediction of complications. Other studies have reported an association between early postoperative PNI and prediction of severe complications following gastrointestinal surgery[15,16,20]. There have been no studies of the use of early postoperative PNI for predicting serious complications following PD. Thus, the aim of our study was to analyze the risk factors and early postoperative PNI for predicting severe complications following PD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and perioperative management

From January 2007 to December 2017, 244 consecutive patients underwent PD at the Department of Surgery in Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand and were considered for inclusion in the study. Patients who underwent concomitant hepatic resection were excluded, which left 238 patients in the study. We retrospectively reviewed patient data, including age, gender, body mass index, underlying disease, ASA classification, history of smoking, serum albumin, preoperative total bilirubin, preoperative diagnosis and preoperative biliary intervention. We also reviewed the pancreatic texture, pancreatic duct size, operating time and operative blood loss. PNI was calculated as follows: albumin level (g/L) + 0.005 × total lymphocyte count (/µL). Ethical permission for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Ramathibodi Hospital.

The surgical procedure has been described in a previous report[4]. PD was performed by surgeons with experience in pancreatic surgery. Pancreatic texture was classified as hard, firm or soft consistency based on palpation by the surgeon. After surgery, patients were transferred to a critical care unit or intermediate ward. Routine biochemical analyses of patients’ blood were performed. An oral diet was started as soon as the output gastric content was < 400 mL and the occurrence of a bowel movement.

Postoperative complications

The postoperative complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification[6]. The complications were confirmed to occur in pancreatic surgery[21]. Serious complications were defined as higher than grade II in the Clavien-Dindo classification[6]. POPF was defined according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) guidelines by amylase levels that were three times higher in the drainage fluid than serum[22]. POPF was classified into three categories: (1) grade biochemical leakage: transient pancreatic fistula with no clinical impact; (2) grade B: required a change in management or adjustment of the clinical course; and (3) grade C: required a major change in clinical management or deviated from the normal clinical course. Delay gastric emptying (DGE), as defined by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery, within 30 d after the index operation[23]. DGE was assessed as present if either nasogastric tube insertion after POD 3 or as the inability to tolerate solid food intake by POD 7. Chyle leakage was defined as a milky drain output or triglyceride level > 110 mg/dL in the drain fluid on any POD. Postoperative mortality was recorded as the 90-d mortality and in-hospital mortality. The patients who the cause of death did not associated with the postoperative complication were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

Categorical and numerical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher exact test and Mann-Whitney test, respectively. Univariate and multivariate (variable selection with stepwise and best subset approaches[24]) analyses were conducted using the logistic regression model. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to assess the strength of the associations between the various factors and postoperative outcome. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using STATA version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States). The cut-off value for high and low PNI was determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

RESULTS

The clinicopathological characteristics of the 238 patients and overall complications are summarized in Table 1. The overall complication rate was 65.97% (157/238 patients). The overall POPF rate was 49.57% (118/238 patients). The clinical relevant (grade B/C) POPF rate was 23.53% (56/238 patients). The overall grade III-V complication rate was 26.47% (63/238 patients). The postoperative mortality rate was 3.78% (9/238 patients). The median follow up period was twenty-four months.

Table 1.

Overall complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy

| Complications, n (%) | Total (n = 238) | ||

| No | 81 (34.03) | ||

| yes | 157 (65.97) | ||

| Postoperative pancreatic fistula | 118 (49.58) | ||

| Grade BL | 62 (26.05) | ||

| Grade B | 38 (15.97) | ||

| Grade C | 18 (7.56) | ||

| Surgical site infection | 32 (13.45) | ||

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 31 (13.02) | ||

| Delayed gastric emptying | 23 (9.66) | ||

| Bile leak | 15 (6.30) | ||

| Chyle leak | 10 (4.20) | ||

| Intraperitoneal hemorrhage | 9 (3.78) | ||

| Acute kidney injury | 8 (3.36) | ||

| Cholangitis | 7 (2.94) | ||

| Lung atelectasis | 5 (2.10) | ||

| Septicemia | 5 (2.10) | ||

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 4 (1.68) | ||

| Pleural effusion | 4 (1.68) | ||

| Pneumonia | 4 (1.68) | ||

| Intestinal obstruction | 3 (1.26) | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 3 (1.26) | ||

| Acute pancreatitis | 2 (0.84) | ||

| Delirium | 2 (0.84) | ||

| Respiratory failure | 2 (0.84) | ||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (0.42) | ||

| Hepatic failure | 1 (0.42) | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (0.42) | ||

| Death | 9 (3.78) | ||

BL: Biochemical leakage.

Patient characteristics and operative outcomes in patients with grade 0-II and III-V complications

Table 2 compares the clinicopathological characteristic between patients with grade 0-II and III-V complications. Age, gender, diabetes mellitus, smoking, previous biliary intervention, total bilirubin, preoperative diagnosis, operating time, blood loss, pancreatic texture and pancreatic duct diameter did not differ significantly between the two groups. The grade III-V group had significantly higher body mass index (22.6 vs 21.85, P < 0.05) and lower serum albumin (34.1 vs 35.0, P < 0.05) than the grade 0-II group had. The patients in the grade III-V complications group had significantly higher ASA status than the grade 0-II group had (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological characteristics in grade 0-II and III-V complication groups

| Data | Total (n = 238) | Grade 0-II (n = 175) | Grade III-V (n = 63) | P | |

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 60.01 (11.01) | 59.89 (11.40) | 60.33 (9.91) | 0.788 | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 125 (52.52) | 95 (54.29) | 30 (47.62) | 0.364 | |

| Female | 113 (47.48) | 80 (45.71) | 33 (52.38) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2), median (range) | 22.10 (15.11-38.95) | 21.85 (15.11-38.95) | 22.65 (16.22-35.34) | < 0.05 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | |||||

| No | 173 (72.69) | 123 (70.29) | 50 (79.37) | 0.165 | |

| Yes | 65 (27.31) | 52 (29.71) | 13 (20.63) | ||

| ASA class, n (%), n = 234 | |||||

| I | 6 (2.56) | 3 (1.75) | 3 (4.76) | < 0.05 | |

| II | 80 (34.19) | 64 (37.43) | 16 (25.40) | ||

| III | 135 (57.69) | 97 (56.73) | 38 (60.32) | ||

| IV | 10 (4.27) | 6 (3.51) | 4 (6.35) | ||

| V | 3 (1.28) | 1 (0.58) | 2 (3.17) | ||

| Smoking, n (%) | |||||

| No | 163 (68.49) | 115 (65.71) | 48 (76.19) | 0.125 | |

| Yes | 75 (31.51) | 60 (34.29) | 15 (23.81) | ||

| Previous biliary intervention, n (%) | |||||

| No | 84 (35.29) | 60 (34.29) | 24 (38.10) | 0.587 | |

| Yes | 154 (64.71) | 115 (65.71) | 39 (61.90) | ||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL), median (range) | 1.20 (0.10-35.0) | 1.20 (0.10-35.0) | 1.30 (0.20-25.0) | 0.956 | |

| Albumin (g/L), median (range) | 34.9 (18.7-49.0) | 35 (18.7-49.0) | 34.1 (23.1-45.0) | < 0.05 | |

| ≥ 35 | 116 (48.47) | 91 (52.0) | 25 (39.68) | 0.093 | |

| < 35 | 122 (51.26) | 84 (48.0) | 38 (60.32) | ||

| Preoperative diagnosis, n (%) | |||||

| Benign | 55 (23.11) | 43 (24.57) | 12 (19.05) | 0.372 | |

| Malignant | 183 (76.89) | 132 (75.43) | 51 (80.95) | ||

| Pancreatic, n (%) | |||||

| Pancreatic | 131 (55.04) | 95 (54.29) | 36 (57.14) | 0.696 | |

| Nonpancreatic | 107 (44.96) | 80 (45.71) | 27 (42.86) | ||

| Operating time, median (range) | 465 (240-900) | 420 (240-900) | 480 (270-840) | 0.175 | |

| Blood loss (mL), median (range), n = 237 | 800 (100-13 000) | 800 (100-8000) | 1000 (150-13 000) | 0.051 | |

| Pancreatic texture, n (%) n=227 | |||||

| Hard firm | 113 (49.78) | 88 (52.69) | 25 (41.67) | 0.143 | |

| Soft | 114 (50.22) | 79 (47.31) | 35 (58.33) | ||

| Pancreatic diameter (mm) median (range), n = 225 | 3 (1-20) | 3 (1-20) | 4 (1-20) | 0.718 | |

| PNI, median (range) | |||||

| Preoperative, n = 230 | 98.9 (0.4-382.2) | 98.9 (0.4-382.2) | 101.5 (39.2-204.9) | 0.456 | |

| POD 1, n = 140 | 49.3 (0.2-111.6) | 56.3 (0.2-425.6) | 45.3 (0.2-111.6) | 0.060 | |

| POD 2, n = 81 | 43.1 (0.2-331.1) | 45.5 (0.2-331.1) | 35.2 (0.2-78.2) | < 0.05 | |

| POD 3, n = 133 | 40.5 (0.1-290.2) | 45.5 (0.2-290.2) | 30.0 (0.1-85.9) | < 0.01 | |

| POD 4, n = 53 | 31.7 (0.2-205.8) | 36.8 (0.2-205.8) | 27.1 (0.2-61.4) | 0.112 | |

| POD 5, n = 70 | 41.0 (0.1-147.4) | 38.7 (0.1-147.4) | 41.8 (0.2-123.2) | 0.396 | |

BMI: Body mass index; PNI: Prognostic nutritional index; POD: Postoperative day; SD: Standard deviation.

Comparison of PNI between grade 0-II and III-V complications

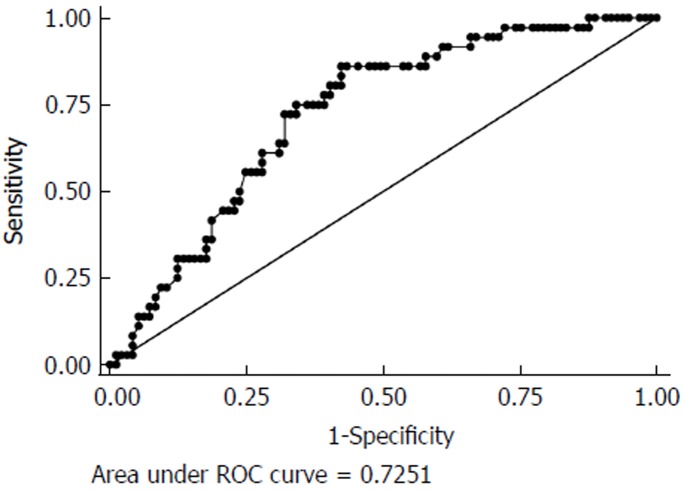

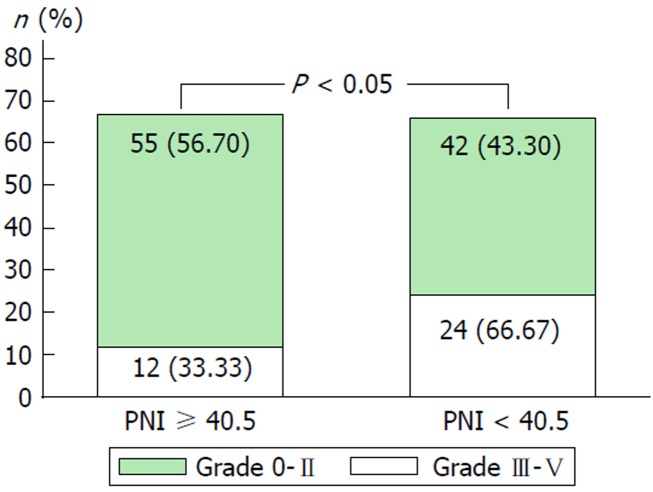

Table 2 compares the pre- and postoperative PNI. Preoperative PNI did not differ between the two groups. The most significant difference in postoperative PNI between the two groups was on POD 3 (45.5 vs 30.0, P < 0.01). Accordingly, we used PNI on POD 3 for analysis of the factors predicting grade III-V postoperative complications. The cut-off value for PNI POD 3 was determined by ROC curve analysis (Figure 1). The area under the ROC curve was 0.72 (sensitivity 72.2%, specificity 68.0%, positive predictive value 0.62, and negative predictive value 0.53, 95%CI: 0.63-0.81). Patients with low PNI (< 40.5) had a significantly higher rate of severe complications than those with high PNI (≥ 40.5) (Figure 2). Thus, POD 3 PNI = 40.5 was considered as the optimal cut-off value.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for predicting grade III-V complications with postoperative day 3 prognostic nutritional index < 40.5. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic.

Figure 2.

Comparison between low (< 40.5) and high (≥ 40.5) postoperative day 3 prognostic nutritional index in grade 0-II and III-V groups. PNI: Prognostic nutritional index.

Analysis of the risk factors for grade III-V complications

The results of univariate and multivariate analyses of potential predictors of grade III-V complications are shown in Table 3. Univariate analysis identified two variables significantly associated with grade III-V complications: preoperative serum albumin (OR: 0.943, 96%CI: 0.89-0.99; P < 0.05), and POD 3 PNI < 40.5 (OR: 2.619, 95%CI: 1.17-5.83; P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis identified two variables as significant predictive factors for grade III-V complications: preoperative serum albumin (OR: 0.88, 95%CI 0.80-0.96; P < 0.01) and POD 3 PNI < 40.5 (OR: 2.77, 95%CI: 1.21-6.38; P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the factors associated with grade III-V complications

| Data |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |||

| Age (yr) | 1.003 (0.97-1.03) | 0.787 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 | |||||

| Female | 1.306 (0.73-2.32) | 0.364 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.055 (0.98-1.13) | 0.135 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| No | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 0.615 (0.31-1.22) | 0.168 | ||||

| ASA class | ||||||

| I | 1 | |||||

| II | 0.250 (0.04-1.35) | 0.108 | ||||

| III | 0.391 (0.07-2.02) | 0.264 | ||||

| IV | 0.667 (0.08-5.12) | 0.697 | ||||

| V | 2.00 (0.11-35.80) | 0.638 | ||||

| Smoking | ||||||

| No | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 0.598 (0.31-1.15) | 0.127 | ||||

| Previous biliary intervention | ||||||

| No | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 0.847 (0.46-1.53) | 0.588 | ||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/d/L) | 0.994 (0.93-1.05) | 0.850 | ||||

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.943 (0.89-0.99) | < 0.05 | 0.883 (0.80-0.96) | < 0.01 | ||

| Preoperative diagnosis | ||||||

| Benign | 1 | |||||

| Malignant | 1.384 (0.67-2.83) | 0.374 | ||||

| Pancreatic | ||||||

| Pancreatic | 1 | |||||

| Nonpancreatic | 0.890 (0.49-1.59) | 0.696 | ||||

| Operating time | 1.002 (0.99-1.01) | 0.154 | ||||

| Blood loss (mL) | 1.254 (1.02-1.54) | 0.030 | ||||

| Pancreatic texture | ||||||

| Hard/firm | 1 | |||||

| Soft | 1.559 (0.85-2.83) | 0.144 | ||||

| Pancreatic diameter (mm) | 0.994 (0.88-1.12) | 0.921 | ||||

| PNI (POD 3) | 0.981 (0.96-0.99) | < 0.05 | ||||

| ≥ 40.5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| < 40.5 | 2.619 (1.17-5.83) | < 0.05 | 2.776 (1.21-6.38) | < 0.05 | ||

BMI: Body mass index; CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; PNI: Prognostic nutritional index; POD: Postoperative day.

DISCUSSION

Perioperative nutritional status is an important factor correlated with postoperative outcomes[25]. Serum albumin is a common indicator for ongoing inflammatory processes, and hypoalbuminemia is a predictor of postoperative morbidity[25-28]. It has been demonstrated that the survival of patients with cachexia is significantly reduced after undergoing resection of pancreatic cancer[29]. In the present study, the independent factors associated with serious postoperative complications following PD were preoperative serum albumin and POD 3 PNI < 40.5.

Albumin is a negative acute phase protein synthesized in the liver at a level of 12-25 g/d and half-life of 20 d. Serum albumin level is affected by multiple factors including malignancy, inflammatory state, trauma and surgery[30]. Hypoalbuminemia is associated with poor tissue healing, decreased collagen synthesis in surgical wounds or at anastomoses, and impairment of immune responses such as macrophage activation and granuloma formation[31,32]. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is significantly associated with postoperative complications following various types of surgery[25,33,34]. Lyu et al[2] reported the risk factors for reoperation in 15549 patients following pancreatic resection, and preoperative serum albumin < 3.5 mg/dL was a predictor for unplanned 30-d reoperation. Moreover, Agustin et al[35] reported the factors related to life-threatening complications and mortality after pancreatic resection in a large population study. They demonstrated that serum albumin < 3.5 g/dL was an independent factor associated with Clavien-Dindo grade IV complications and mortality in the pancreatic surgery patients[35]. According to these reports, we conclude that preoperative hypoalbuminemia is a significant risk factor for serious postoperative complications, especially after pancreatic resection.

C-reactive protein and procalcitonin are inflammatory markers and accurate predictors for infectious complications following surgery[10,36]. However, in hospitals with limited resources, such as in Thailand, those markers are expensive. Moreover, procalcitonin examination is not available in all hospitals. So, those markers are not routinely used in our hospital. However, there is the simple inexpensive inflammatory marker PNI. PNI was first proposed by Onodera et al[17] as a predictor of surgical complications and mortality. PNI depends on two parameters, serum albumin and total lymphocyte count from peripheral blood smears[17]. Several studies have reported that low preoperative PNI is associated with postoperative complications[13,16,37,38]. However, for postoperative PNI, only one study has reported the association between decreased PNI on POD 7 following distal pancreatectomy, which showed that decreased PNI on POD 7 was a predictor for POPF[19]. However, the definitive diagnosis of POPF was on POD 3. Evaluation on POD 7 seemed to delay diagnosis. In our study, POD 3 PNI < 40.5 was a significant independent factor associated with serious postoperative complications following PD. This evidence was supported by Noji et al[39], who reported that infectious complications following PD could be predicted by amylase levels in drain effluent, body temperature, and leukocyte count on POD 3[39].

Postoperative PNI value might be associated with hypoalbuminemia because serum albumin level is an important parameter in PNI[40]. It has been shown that early postoperative serum albumin is associated with postoperative complications[40,41]. The stress response to injury is a factor that contributes to low postoperative serum albumin[28,42]. Labgaa et al[43] reported that patients who had a > 10 g/L decrease in serum albumin on POD 1 showed a threefold increased risk of overall postoperative complications after major surgery that lasted > 2 h. They concluded that the decrease in serum albumin was a marker of surgical stress response and early predictor of clinical outcomes. Moreover, the decrease in serum albumin significantly correlated with the extent of surgery, and the maximal increase in other stress markers such as C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and lactate[43].

There is evidence that low postoperative serum albumin is associated with outcome following PD[44,45]. Kawai et al[44] reported that serum albumin level ≤ 3.0 g/dL on POD 4 and leukocyte count > 9800/mm were independent predictive factors of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula following PD. Similarly, Fujiwara et al[45] reported that low postoperative serum albumin was an independent risk factor for POPF after PD[45]. According to these reports, low PNI in the early postoperative period could be a predictor for serious complications following PD. Post-PD patients who have low PNI on POD 3 should be closely monitored for serious complications. In our hospital, routine CT is not performed following PD. According to the present study, computed tomography should be selectively performed in patients who have low PNI on POD 3, especially in those with POPF. However, the prospective studies are needed to validate this hypothesis.

This study had several limitations. First, because of its retrospective nature, there could have been some selection bias. Second, postoperative serum albumin could have been affected by exogenous intravenous albumin that was administered to some patients. However, our hospital policy is that only patients with serum albumin < 25 g/L are eligible for intravenous albumin. Third, the lower serum albumin between two groups (34.1 versus 35.0 g/L) is a modest difference. Fourth, the further prospective studies are needed to enhance the ability of POD 3 PNI < 40.5 to predict serious complications following PD.

In conclusion, Perioperative albumin is an important factor associated with serious complications following PD. POPF is a common complication following PD; however, most POPFs are minor complications and do not need any intervention. The most important consideration in clinical practice is that physicians should be aware of serious complications after PD. Our study suggests that PNI, which is a simple and inexpensive marker, is a good predictor for serious complications. Thus, patients who undergo PD and have early postoperative low PNI should be closely monitored.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is an example of major surgery and is a complicated operation to perform for the general surgeon. The perioperative morbidity rate previously reported reaching up to 50%. However, only serious complications are major risk factors for poor long-term surgical outcome. Majority of the serious complications is the infectious complication.

Research motivation

There are several studies have investigated the use of inflammatory markers for prediction of severe postoperative complications following PD. However, the common biomarkers previously reported are C-reactive protein and procalcitonin. These biomarkers are expensive in the limited resource country. Our goal is to find the simple and non-expensive marker for this complicated operation. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) is one of a simple inexpensive marker. There are previously reported of early postoperative PNI predicted the outcome following surgery.

Research objectives

The objective of our study was to analyze the risk factors and early postoperative PNI for predicting serious complications following PD.

Research methods

From January 2007 to December 2017, 244 consecutive patients underwent PD at the Department of Surgery in Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand and were retrospectively reviewed. The patients were classified into two groups (grade I-II and III-V complication groups according to Dindo-Clavien classification). Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted. The cut-off value for high and low PNI was determined by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis

Research results

The independent factors associated with serious postoperative complications following PD were preoperative serum albumin and POD 3 PNI value < 40.5. To the best of our knowledge, we first time reported the early postoperative prognostic index as a predictor of the serious postoperative complication following PD. The hypoalbuminemia is the main factor associated with serious postoperative complications according to previous reports.

Research conclusions

PNI, which is a simple and inexpensive marker, is a good predictor for serious complications. Thus, patients who undergo PD and have early postoperative low PNI should be aware of serious complication especially infectious complications.

Research perspectives

The well designed prospective studies are needed to validate this predictor.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Thailand

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ramathibodi Hospital Institutional Review Board Committee on Human Rights Related to Research Involving Human Subjects (protocol number ID 07-61-25).

Informed consent statement: Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare no conflicts-of-interest related to this article.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: September 6, 2018

First decision: October 19, 2018

Article in press: December 21, 2018

P- Reviewer: Zhang Z, Niu ZS, Koch TR, Aoki H S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Bian YN

Contributor Information

Narongsak Rungsakulkij, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand. narongsak.run@mahidol.ac.th.

Pongsatorn Tangtawee, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

Wikran Suragul, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

Paramin Muangkaew, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

Somkit Mingphruedhi, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

Suraida Aeesoa, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

References

- 1.Ammori JB, Choong K, Hardacre JM. Surgical Therapy for Pancreatic and Periampullary Cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:1271–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyu HG, Sharma G, Brovman E, Ejiofor J, Repaka A, Urman RD, Gold JS, Whang EE. Risk Factors of Reoperation After Pancreatic Resection. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1666–1675. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4546-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMillan MT, Soi S, Asbun HJ, Ball CG, Bassi C, Beane JD, Behrman SW, Berger AC, Bloomston M, Callery MP, Christein JD, Dixon E, Drebin JA, Castillo CF, Fisher WE, Fong ZV, House MG, Hughes SJ, Kent TS, Kunstman JW, Malleo G, Miller BC, Salem RR, Soares K, Valero V, Wolfgang CL, Vollmer CM Jr. Risk-adjusted Outcomes of Clinically Relevant Pancreatic Fistula Following Pancreatoduodenectomy: A Model for Performance Evaluation. Ann Surg. 2016;264:344–352. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rungsakulkij N, Mingphruedhi S, Tangtawee P, Krutsri C, Muangkaew P, Suragul W, Tannaphai P, Aeesoa S. Risk factors for pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy: A retrospective study in a Thai tertiary center. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;9:270–280. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v9.i12.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen JY, Feng J, Wang XQ, Cai SW, Dong JH, Chen YL. Risk scoring system and predictor for clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5926–5933. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smits FJ, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Batenburg MCT, Slooff RAE, Boerma D, Busch OR, Coene PPLO, van Dam RM, van Dijk DPJ, van Eijck CHJ, Festen S, van der Harst E, de Hingh IHJT, de Jong KP, Tol JAMG, Borel Rinkes IHM, Molenaar IQ; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Management of Severe Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreatoduodenectomy. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:540–548. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMillan MT, Vollmer CM Jr, Asbun HJ, Ball CG, Bassi C, Beane JD, Berger AC, Bloomston M, Callery MP, Christein JD, Dixon E, Drebin JA, Castillo CF, Fisher WE, Fong ZV, Haverick E, House MG, Hughes SJ, Kent TS, Kunstman JW, Malleo G, McElhany AL, Salem RR, Soares K, Sprys MH, Valero V 3rd, Watkins AA, Wolfgang CL, Behrman SW. The Characterization and Prediction of ISGPF Grade C Fistulas Following Pancreatoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:262–276. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2884-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ecker BL, McMillan MT, Asbun HJ, Ball CG, Bassi C, Beane JD, Behrman SW, Berger AC, Dickson EJ, Bloomston M, Callery MP, Christein JD, Dixon E, Drebin JA, Castillo CF, Fisher WE, Fong ZV, Haverick E, Hollis RH, House MG, Hughes SJ, Jamieson NB, Javed AA, Kent TS, Kowalsky SJ, Kunstman JW, Malleo G, Poruk KE, Salem RR, Schmidt CR, Soares K, Stauffer JA, Valero V, Velu LKP, Watkins AA, Wolfgang CL, Zureikat AH, Vollmer CM Jr. Characterization and Optimal Management of High-risk Pancreatic Anastomoses During Pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2018;267:608–616. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welsch T, Frommhold K, Hinz U, Weigand MA, Kleeff J, Friess H, Büchler MW, Schmidt J. Persisting elevation of C-reactive protein after pancreatic resections can indicate developing inflammatory complications. Surgery. 2008;143:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solaini L, Atmaja BT, Watt J, Arumugam P, Hutchins RR, Abraham AT, Bhattacharya S, Kocher HM. Limited utility of inflammatory markers in the early detection of postoperative inflammatory complications after pancreatic resection: Cohort study and meta-analyses. Int J Surg. 2015;17:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamieson NB, Glen P, McMillan DC, McKay CJ, Foulis AK, Carter R, Imrie CW. Systemic inflammatory response predicts outcome in patients undergoing resection for ductal adenocarcinoma head of pancreas. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:21–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanda M, Fujii T, Kodera Y, Nagai S, Takeda S, Nakao A. Nutritional predictors of postoperative outcome in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98:268–274. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Li C, Wen T, Peng W, Yan L, Yang J. Postoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Survival of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma within Milan Criteria and Hypersplenism. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1626–1634. doi: 10.1007/s11605-017-3414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou W, Cao Q, Qi W, Xu Y, Liu W, Xiang J, Xia B. Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Short-Term Postoperative Outcomes After Bowel Resection for Crohn’s Disease. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017;32:92–97. doi: 10.1177/0884533616661844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohri Y, Inoue Y, Tanaka K, Hiro J, Uchida K, Kusunoki M. Prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative outcome in colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:2688–2692. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onodera T, Goseki N, Kosaki G. [Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients] Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;85:1001–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim E, Kang JS, Han Y, Kim H, Kwon W, Kim JR, Kim SW, Jang JY. Influence of preoperative nutritional status on clinical outcomes after pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20:1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato N, Mori Y, Minagawa N, Tamura T, Shibao K, Higure A, Yamaguchi K. Rapid postoperative reduction in prognostic nutrition index is associated with the development of pancreatic fistula following distal pancreatectomy. Pancreatology. 2014;14:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Q, Wang G, Ren J, Ren H, Li G, Wu X, Gu G, Li R, Guo K, Deng Y, Li Y, Hong Z, Wu L, Li J. Preoperative prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative surgical site infections in gastrointestinal fistula patients undergoing bowel resections. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4084. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Clavien PA. Assessment of complications after pancreatic surgery: A novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2006;244:931–7; discussion 937-9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000246856.03918.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CR, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery. 2017;161:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW, Yeo CJ, Büchler MW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Surgery. 2007;142:761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z. Variable selection with stepwise and best subset approaches. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:136. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.03.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa MD, Vieira de Melo CY, Amorim AC, Cipriano Torres Dde O, Dos Santos AC. Association Between Nutritional Status, Inflammatory Condition, and Prognostic Indexes with Postoperative Complications and Clinical Outcome of Patients with Gastrointestinal Neoplasia. Nutr Cancer. 2016;68:1108–1114. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2016.1206578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hennessey DB, Burke JP, Ni-Dhonochu T, Shields C, Winter DC, Mealy K. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is an independent risk factor for the development of surgical site infection following gastrointestinal surgery: a multi-institutional study. Ann Surg. 2010;252:325–329. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e9819a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z; Ad Hoc ESPEN Working Group. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:321–336. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(02)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, Higashiguchi T, Hübner M, Klek S, Laviano A, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN, Martindale R, Waitzberg DL, Bischoff SC, Singer P. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:623–650. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachmann J, Heiligensetzer M, Krakowski-Roosen H, Büchler MW, Friess H, Martignoni ME. Cachexia worsens prognosis in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1193–1201. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0505-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuhrman MP, Charney P, Mueller CM. Hepatic proteins and nutrition assessment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1258–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.05.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivadeneira DE, Grobmyer SR, Naama HA, Mackrell PJ, Mestre JR, Stapleton PP, Daly JM. Malnutrition-induced macrophage apoptosis. Surgery. 2001;129:617–625. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.112963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds JV, Redmond HP, Ueno N, Steigman C, Ziegler MM, Daly JM, Johnston RB Jr. Impairment of macrophage activation and granuloma formation by protein deprivation in mice. Cell Immunol. 1992;139:493–504. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adogwa O, Martin JR, Huang K, Verla T, Fatemi P, Thompson P, Cheng J, Kuchibhatla M, Lad SP, Bagley CA, Gottfried ON. Preoperative serum albumin level as a predictor of postoperative complication after spine fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:1513–1519. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ataseven B, du Bois A, Reinthaller A, Traut A, Heitz F, Aust S, Prader S, Polterauer S, Harter P, Grimm C. Pre-operative serum albumin is associated with post-operative complication rate and overall survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer undergoing cytoreductive surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:560–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Augustin T, Burstein MD, Schneider EB, Morris-Stiff G, Wey J, Chalikonda S, Walsh RM. Frailty predicts risk of life-threatening complications and mortality after pancreatic resections. Surgery. 2016;160:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Facy O, Paquette B, Orry D, Binquet C, Masson D, Bouvier A, Fournel I, Charles PE, Rat P, Ortega-Deballon P; IMACORS Study. Diagnostic Accuracy of Inflammatory Markers As Early Predictors of Infection After Elective Colorectal Surgery: Results From the IMACORS Study. Ann Surg. 2016;263:961–966. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang N, Deng JY, Ding XW, Ke B, Liu N, Zhang RP, Liang H. Prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative complications and long-term outcomes of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10537–10544. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokunaga R, Sakamoto Y, Nakagawa S, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N, Oki E, Watanabe M, Baba H. Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Severe Complications, Recurrence, and Poor Prognosis in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Primary Tumor Resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:1048–1057. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noji T, Nakamura T, Ambo Y, Suzuki O, Nakamura F, Kishida A, Hirano S, Kondo S, Kashimura N. Clinically relevant pancreas-related infectious complication after pancreaticoenteral anastomosis could be predicted by the parameters obtained on postoperative day 3. Pancreas. 2012;41:916–921. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31823e7705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hübner M, Mantziari S, Demartines N, Pralong F, Coti-Bertrand P, Schäfer M. Postoperative Albumin Drop Is a Marker for Surgical Stress and a Predictor for Clinical Outcome: A Pilot Study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:8743187. doi: 10.1155/2016/8743187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Labgaa I, Joliat GR, Demartines N, Hübner M. Serum albumin is an early predictor of complications after liver surgery. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neel DR, McClave S, Martindale R. Hypoalbuminaemia in the perioperative period: clinical significance and management options. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2011;25:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Labgaa I, Joliat GR, Kefleyesus A, Mantziari S, Schäfer M, Demartines N, Hübner M. Is postoperative decrease of serum albumin an early predictor of complications after major abdominal surgery? A prospective cohort study in a European centre. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013966. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawai M, Tani M, Hirono S, Ina S, Miyazawa M, Yamaue H. How do we predict the clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy?--an analysis in 244 consecutive patients. World J Surg. 2009;33:2670–2678. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujiwara Y, Shiba H, Shirai Y, Iwase R, Haruki K, Furukawa K, Futagawa Y, Misawa T, Yanaga K. Perioperative serum albumin correlates with postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]