Abstract

Background

Vedolizumab inhibits α4β7-mediated lymphocyte trafficking and is effective in ulcerative colitis (UC). This study evaluated drug and biomarker concentrations and patient outcomes during vedolizumab treatment in UC.

Methods

Prospectively scored maintenance clinical (26.5 weeks; interquartile range [IQR], 16.3–37.0 weeks) and endoscopic (23.5 weeks; IQR, 16.8–35.6 weeks) outcomes were compared with serum vedolizumab concentrations, antivedolizumab antibodies, and serum biomarkers at baseline and weeks 2, 6, 14, and 26. A linear mixed-effects model compared biomarker trajectories over time between clinical and endoscopic remitters and nonremitters.

Results

Thirty-two patients were included. Soluble (s)–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α, s-α4β7, s-mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule (s-MAdCAM-1), and s-amyloid A (s-AA) significantly changed with treatment. A linear mixed-effects model demonstrated that s-α4β7 (P = 0.044) increased and s-MAdCAM-1 (P = 0.006) and s-vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (s-VCAM-1, P = 0.001) decreased more rapidly in patients achieving clinical remission in maintenance. S-MAdCAM-1 (P = 0.005), s-intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; P = 0.014), s-VCAM-1 (P < 0.001), and s-TNF (P = 0.052) decreased more rapidly in endoscopic remitters. In clinical remitters, higher week 14 (20.3 ng/mL vs 6.0 ng/mL; P = 0.013) and week 26 (14.1 ng/mL vs 8.6 ng/mL; P = 0.05) s-α4β7 were observed. In endoscopic remitters, week 2 (6.7 pg/mL vs 17.8 pg/mL; P = 0.038) and week 6 (3.9 pg/mL vs 15.6 pg/mL; P = 0.005) s-TNF and week 14 s-VCAM (589.1 ng/mL vs 746.0 ng/mL; P = 0.05) were lower.

Conclusion

Serum biomarkers were associated with outcomes in vedolizumab-treated UC patients. s-α4β7 increased, whereas s-MAdCAM-1, s-VCAM-1, s-ICAM-1, and s-TNF decreased more rapidly in remitters. At individual time points, induction s-TNF and maintenance s-VCAM-1 concentrations were lower, whereas maintenance s-α4β7 concentrations were higher in remitters.

Keywords: vedolizumab, ulcerative colitis, biomarkers, personalized medicine

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affecting the colonic mucosa. Vedolizumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against the α4β7 integrin, selectively blocks leukocyte binding to the gut endothelium, which expresses mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1).1 Many UC patients will not respond to vedolizumab.2–5 Thus, biomarkers are needed to predict outcomes.6–9

Vedolizumab concentrations correlate with outcomes, but there is ambiguity about the optimal time points and target cutoffs. Week 6 trough concentrations in the GEMINI trials correlated with clinical remission and mucosal healing (MH) in UC, with improved outcomes for concentrations above 16–19 mcg/mL.10, 11 Observational studies demonstrated variable exposure–response relationships.9, 12–14

Early and late mechanism-specific biomarkers are needed to identify which patients would benefit from either dose escalation or switching medication classes. The α4β7 integrin is a transmembrane cell adhesion protein expressed on lymphocytes and innate immune cells.15, 16 Flow cytometry on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in vedolizumab-treated patients has demonstrated near-complete occupancy of transmembrane α4β7 during induction and maintenance.9 Several studies have analyzed transmembrane α4β7 expression using flow cytometry,17, 18 but none has assessed free soluble (s)-α4β7.

Cellular adhesion molecule (CAM) expression may either change as a consequence of vedolizumab therapy or alter the efficacy of therapy. In the setting of inflammation, TNF induces expression of transmembrane (tissue) MAdCAM-1, the ligand for α4β7 in the gastrointestinal mucosal endothelium.19, 20 Soluble (s)-MAdCAM-1, an indirect measure of transmembrane MAdCAM-1 expression,21 has a pharmacodynamic relationship with MAdCAM-1 antagonist therapy.22 Vedolizumab does not inhibit cell interactions with transmembrane vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) or intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1).23 However, both are upregulated with intestinal inflammation,24–26 and soluble s-ICAM and s-VCAM are indirect measures of transmembrane expression. TNF antagonist–treated CD patients with MH had lower concentrations of s-ICAM, s-TNF, s-C-reactive protein (s-CRP) and serum amyloid A (s-AA), but not s-VCAM-1. S-AA, a TNF-induced acute phase reactant, correlated with endoscopic disease in patients with normal CRP.27 s-AA has not been examined in vedolizumab-treated patients or in UC patients.

We prospectively analyzed serum biomarkers, vedolizumab concentrations, and antivedolizumab antibodies (ATVs) throughout vedolizumab therapy in UC patients. We compared vedolizumab and biomarker concentrations to maintenance clinical and endoscopic outcomes.

METHODS

Patient Selection

Eligible subjects were adults with a confirmed UC diagnosis undergoing vedolizumab treatment at the University of California, San Diego IBD Center. Patients received vedolizumab 300 mg intravenously during induction at weeks 0, 2, 6, then maintenance infusions every 8 weeks. Dose escalation to every 4 weeks was based on provider assessment after induction.

Ethics

The protocol was approved by the local institutional review board, and patients provided informed consent before enrollment.

Sample Collection

Serum was prospectively obtained immediately before vedolizumab infusions during induction at weeks 0 (baseline), 2, and 6 and during maintenance at weeks 14 and ≥26 between January 2014 and October 2016. Biomarker analysis included 1 patient sample per time point.

End Points and Definitions

Clinical and endoscopic scoring was performed prospectively. Disease extent was defined using the Montreal classification.28 Outcomes included clinical remission (physician global assessment [PGA] = 0 and neither treatment discontinuation nor colectomy) and endoscopic remission (Mayo endoscopic subscores [ESS] = 0 or 1). Biomarker concentrations at baseline and weeks 2, 6, 14, and ≥ 26 were compared between remitters and nonremitters for clinical and endoscopic outcomes assessed during maintenance. Correlations between vedolizumab and individual biomarker concentrations, and between s-TNF and s-ICAM-1, s-VCAM-1, and s-α4β7, were explored. This was performed separately during induction and maintenance using the latest available sample collection in each phase. Corticosteroid effects on biomarker concentrations were evaluated. Baseline biomarker concentrations were compared based on baseline systemic corticosteroid requirement. This was repeated for corticosteroid requirement at ≥week 26.

Biomarker Assays

Vedolizumab and ATV measurements used a homogenous mobility shift assay (HMSA), Anser VDZ (Prometheus Laboratories Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Serum TNF measurements used the Erenna SMC Human TNFα Immunoassay Kit (EMD Millipore, St. Charles, MO, USA). CRP, s-AA, s-ICAM-1, and s-VCAM-1 measurements used V-Plex Vascular Injury Panel-2 (human) Kits (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD, USA). sMAdCAM-1 and s-α4β7 measurements used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA; Prometheus Laboratories Inc.)

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized by mean ± standard deviation and median with interquartile range (IQR), respectively, for normally and non–normally distributed data. Percentages were used for categorical variables. Between-group comparisons were performed using the Fisher exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test for categorical and continuous independent data, with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test used for paired continuous data. We fit linear mixed-effects models with each biomarker as the outcome and included baseline biomarker values, time (continuous), and remission status as covariates, with an interaction term between time and remission status to investigate differences in longitudinal trends. We used likelihood ratio tests to choose a parsimonious random effects structure for each model, and an independent random intercept and slope was indicated in each case. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated between vedolizumab and individual biomarker concentrations, and between s-TNF and s-ICAM-1, and s-VCAM-1 and s-α4β7. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 7.03 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA), or R29 (lme4 package,30 for linear mixed-effects models).

RESULTS

Patients

Of 32 included patients (baseline samples: n = 18; week 2: n = 12; week 6: n = 14; week 14: n = 16; ≥week 26: n = 20), 81% had extensive colitis, 56% had severe endoscopic baseline disease (EES = 3), and 84.4% had prior TNF antagonist exposure (Table 1). At baseline, 34% received concomitant immunosuppression (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate-mofetil). The median time to assessment (IQR) was 26.5 (16.3–37.0) weeks for clinical remission and 23.5 (16.8–35.6) weeks for endoscopy.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Baseline Characteristics | n = 32 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46.4 (18.2) |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 8 (31.3) |

| Age at diagnosis, No. (%) | |

| <16 y | 2 (6.3) |

| 16–40 y | 16 (50.0) |

| >40 y | 14 (43.8) |

| Disease duration, mean (SD), y | 7.7 (7.1) |

| Disease extent, No. (%) | |

| Proctitis | 2 (6.3) |

| Left-sided colitis | 4 (12.5) |

| Extensive colitis | 26 (81.3) |

| Current smoker, No. (%) | 2 (6.3) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 26.8 (6) |

| Prior TNF inhibitor use, No. (%) | 27 (84.4) |

| Baseline albumin, mean (SD), g/dL | 4 (0.3) |

| Mean baseline partial Mayo score (SD) | 6 (1.9) |

| Mean baseline Mayo score endoscopic subscore (SD) | 2.5 (0.7) |

| Baseline corticosteroid requirement, No. (%) | 22 (68.8) |

| Concomitant immunomodulator use, No. (%) | 11 (34.4) |

| Dose escalation, No. (%) | 16 (50.0) |

Patient Outcomes

At the time of assessment, 14 patients (46.7%) achieved clinical remission, 19 (59.4%) achieved endoscopic remission, 20 (74.1%) were corticosteroid-free, and 16 (50.0%) underwent dose escalation (median time [IQR], 26 [19–56] weeks). The proportions of TNF antagonist-naïve patients were not significantly different between patients achieving endoscopic remission (10.5%, n = 19) and those not achieving endoscopic remission (21.4%, n = 14; P = 0.40).

Vedolizumab and Antivedolizumab Antibody Concentrations

Median vedolizumab concentrations at weeks 2, 6, 14, and 26 (IQR) were 20 (16–27), 20 (9–25), 12 (7–17), and 10 (8–27) mcg/mL, respectively. ATVs were detected in 2 patients (5.9%). Both received vedolizumab monotherapy, with ATV detection at week 2. In 1 patient, antibodies persisted, dose escalation failed, and colectomy was required. Another transiently developed antibodies until week 6, with detectable vedolizumab. Dose escalation resulted in MH without further ATVs. Although vedolizumab concentrations at any time point were not significantly associated with week 26 outcomes (Supplementary Table 1), induction concentrations were numerically higher in clinical and endoscopic remitters. ATVs were not associated with outcomes.

Biomarkers

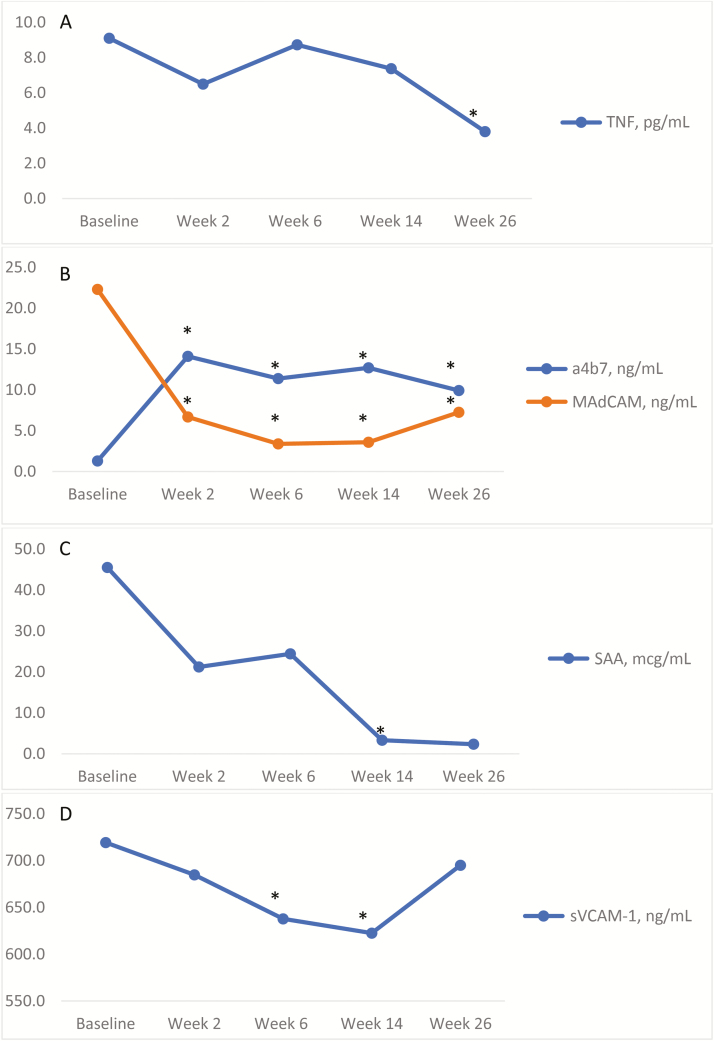

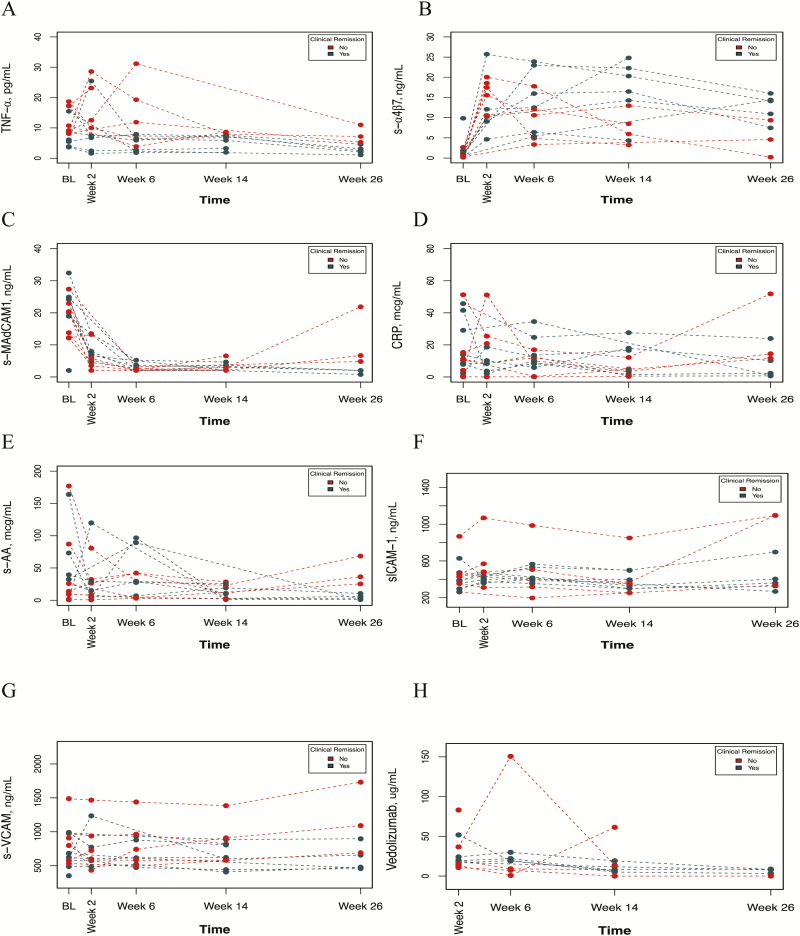

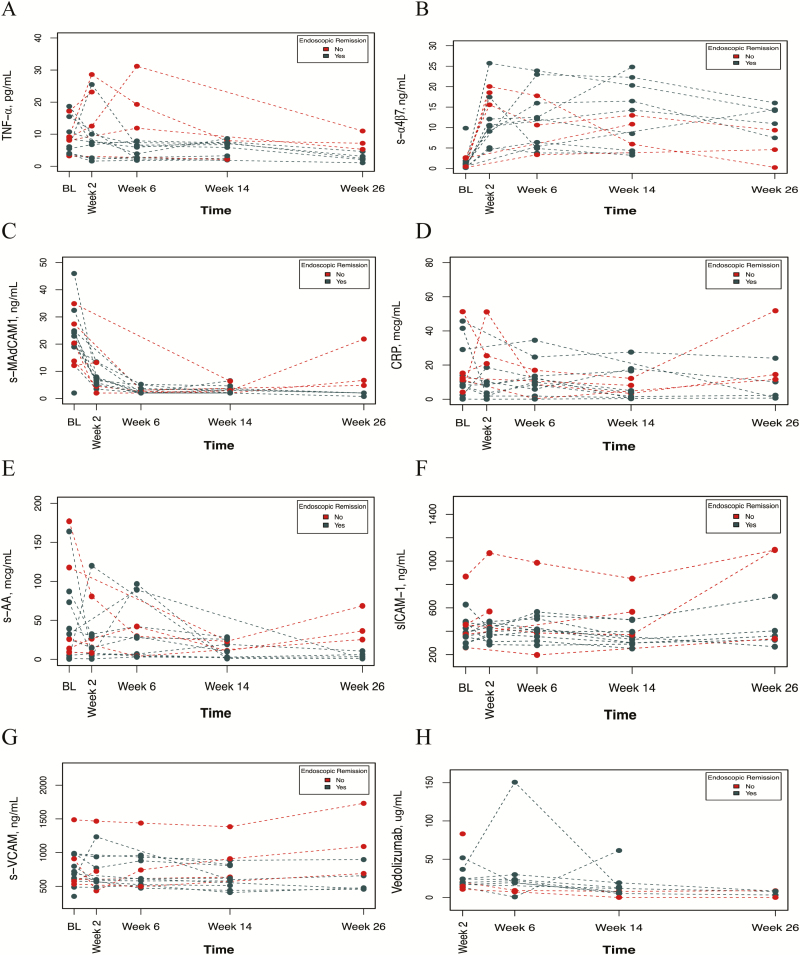

For each biomarker, 3 analyses were performed. First, changes in biomarker concentrations with treatment were reported for all patients (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 2). Second, comparisons for biomarker trajectories over time between clinical or endoscopic remitters to nonremitters are described (using linear mixed-effects models) (Figs. 2 and 3). For all mixed models’ fit, a random intercept alone was determined to be the best random-effect structure. The rate (slope) of increase or decrease between groups was compared (herein referred to as more rapid increase or decline). Lastly, comparisons of biomarker concentrations at individual time points (weeks 2, 6, 14, and 26) between clinical and endoscopic remitters to nonremitters are reported (Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively).

FIGURE 1.

Changes in biomarkers with vedolizumab therapy. In patients with baseline biomarkers before vedolizumab therapy, s-TNF concentrations (A) decreased at week 26. s-α4β7 and s-MAdCAM-1 significantly changed at every time point measured (B). s-AA concentrations (C) significantly decreased at week 14 and trended toward lower concentrations at week 26, with lower sample sizes than previous time points (Supplementary Table 1). s-VCAM-1 changed at weeks 6 and 14, but these changes did not persist later during maintenance at week 26 (D).

FIGURE 2.

Biomarker trends over time by clinical remission. Using a linear mixed effects model, each biomarker (s-TNF (A), s-α4β7 (B), s-MAdCAM-1 (C), CRP (D), s-AA (E), s-ICAM-1 (F), s-VCAM-1 (G)) and vedolizumab concentrations (H) were compared over time between patients who achieved clinical remission in maintenance and those who did not. A significant interaction between time and clinical remission was observed with s-α4β7 (P = 0.044), s-MAdCAM-1 (P = 0.006), and s-VCAM-1 (P = 0.001), with s-α4β7 increasing faster in those who achieved clinical remission and s-MAdCAM-1 and s-VCAM-1 decreasing faster in those who achieved clinical remission. This was not observed with s-TNF (P = 0.22), CRP (P = 0.44), S-AA (P = 0.07), s-ICAM-1 (P = 0.07), or vedolizumab concentrations (P = 0.49).

FIGURE 3.

Biomarker trends over time by endoscopic remission. Using a linear mixed effects model, each biomarker (s-TNF (A), s-α4β7 (B), s-MAdCAM-1 (C), CRP (D), S-AA (E), s-ICAM-1 (F), s-VCAM-1 (G)) and vedolizumab concentrations (H) were compared over time between patients who achieved endoscopic remission in maintenance and those who did not. A significant interaction between time and endoscopic remission with s-MAdCAM-1 (P = 0.005), s-ICAM-1 (P = 0.014), and s-VCAM-1 (P < 0.001) was found, with each decreasing faster in those who achieved endoscopic remission. A trend for this was found with s-TNF concentrations (P = 0.052) and s-α4β7 (P = 0.07), but not for CRP (P = 0.075), SSA (P = 0.14), or vedolizumab (P = 0.47) concentrations.

Table 2.

Associations of Week 2 Biomarkers With Maintenance Outcomes

| Median | IQR 25 to 75 | No. | Median | IQR 25 to 75 | No. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Remission | No Clinical Remission | ||||||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 6.7 | 2.4 to 7.5 | 5 | 12.5 | 10.6 to 23.2 | 5 | NS |

| α4β7, ng/mL | 10.2 | 9.1 to 12.1 | 5 | 16.5 | 15.6 to 18.3 | 6 | NS |

| α4β7, change from baseline, ng/mL | 9.7 | 7.2 to 11.9 | 5 | 16.1 | 12.9 to 18.1 | 5 | NS |

| MAdCAM-1, ng/mL | 7.1 | 6.6 to 7.9 | 5 | 5.2 | 3.8 to 6.2 | 6 | NS |

| SAA, mcg/mL | 14.7 | 5.4 to 29.7 | 5 | 29.3 | 12.8 to 41.8 | 6 | NS |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL | 599.4 | 573.5 to 771.5 | 5 | 658.0 | 585.9 to 884.0 | 6 | NS |

| s-VCAM, change from baseline, ng/mL | –2.5 | –22.6 to 78.0 | 5 | –36.4 | –213.9 to –20.4 | 5 | NS |

| CRP, mcg/mL | 8.3 | 3.6 to 10.2 | 5 | 15.3 | 8.9 to 24.3 | 6 | NS |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL | 396.1 | 375.7 to 421.6 | 5 | 465.5 | 435.0 to 547.5 | 6 | NS |

| Endoscopic Remission | No Endoscopic Remission | ||||||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 6.7 | 2.5 to 8.8 | 7 | 17.8 | 12.1 to 24.5 | 4 | 0.038 |

| α4β7, ng/mL | 10.4 | 8.1 to 13.4 | 8 | 17.1 | 15.6 to 18.9 | 4 | NS |

| α4β7, change from baseline, ng/mL | 10.0 | 6.6 to 13.0 | 8 | 18.1 | 15.5 to 18.9 | 3 | NS |

| MAdCAM-1, ng/mL | 6.8 | 5.6 to 7.7 | 8 | 5.4 | 3.9 to 8.0 | 4 | NS |

| SAA, mcg/mL | 11.1 | 5.2 to 30.4 | 8 | 35.7 | 21.9 to 53.8 | 4 | NS |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL | 591.4 | 571.8 to 813.0 | 8 | 658.0 | 552.9 to 909.1 | 4 | NS |

| s-VCAM, change from baseline, ng/mL | –29.5 | –168.5 to 17.6 | 8 | –20.4 | –247.6 to 65.2 | 3 | NS |

| CRP, mcg/mL | 6.0 | 2.0 to 9.0 | 8 | 23.1 | 18.1 to 31.9 | 4 | 0.017 |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL | 385.9 | 347.8 to 434.4 | 8 | 508.6 | 443.8 to 693.9 | 4 | 0.042 |

Biomarker concentrations measured at week 2 are stratified based on the achievement of clinical and endoscopic remission during maintenance.

Table 3.

Associations of Week 6 Biomarkers With Maintenance Outcomes

| Median | IQR 25 to 75 | No. | Median | IQR 25 to 75 | No. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Remission | No Clinical Remission | ||||||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 5.9 | 2.5 to 7.1 | 7 | 11.9 | 6.6 to 19.3 | 5 | NS |

| α4β7, ng/mL | 12.5 | 6.1 to 19.5 | 7 | 10.6 | 4.9 to 12.1 | 5 | NS |

| α4β7, change from baseline, ng/mL | 13.2 | 7.7 to 20.0 | 6 | 7.9 | 3.6 to 11.9 | 5 | NS |

| MAdCAM-1, ng/mL | 2.0 | 2.0 to 3.4 | 7 | 2.0 | 2.0 to 2.7 | 5 | NS |

| SAA, mcg/mL | 27.5 | 5.5 to 59.0 | 7 | 29.6 | 3.9 to 42.0 | 5 | NS |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL | 616.0 | 565.3 to 769.9 | 7 | 742.4 | 580.4 to 962.3 | 5 | NS |

| s-VCAM, change from baseline, ng/mL | –59.1 | –94.6 to –16.4 | 6 | –49.5 | –165.6 to –35.4 | 5 | NS |

| CRP, mcg/mL | 10.0 | 7.1 to 19.1 | 7 | 8.7 | 0.3 to 12.0 | 5 | NS |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL | 416.1 | 403.5 to 491.6 | 7 | 385.1 | 316.7 to 506.6 | 5 | NS |

| Endoscopic Remission | No Endoscopic Remission | ||||||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 3.9 | 2.3 to 6.4 | 9 | 15.6 | 11.5 to 22.3 | 4 | 0.005 |

| α4β7, ng/mL | 12.1 | 5.4 to 16.0 | 9 | 8.2 | 5.2 to 12.4 | 4 | NS |

| α4β7, change from baseline, ng/mL | 11.9 | 4.8 to 14.1 | 9 | 7.9 | 5.5 to 12.7 | 3 | NS |

| MAdCAM-1, ng/mL | 2.0 | 2.0 to 3.1 | 9 | 2.4 | 2.0 to 2.8 | 4 | NS |

| SAA, mcg/mL | 27.5 | 6.1 to 42.0 | 9 | 16.8 | 3.2 to 32.7 | 4 | NS |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL | 611.3 | 524.0 to 879.3 | 9 | 728.4 | 660.0 to 916.1 | 4 | NS |

| s-VCAM, change from baseline, ng/mL | –70.7 | –109.7 to –11.7 | 9 | –49.5 | –107.6 to –42.4 | 3 | NS |

| CRP, mcg/mL | 10.0 | 5.9 to 13.5 | 9 | 5.2 | 1.3 to 10.8 | 4 | NS |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL | 406.6 | 354.3 to 506.6 | 9 | 418.6 | 338.2 to 585.5 | 4 | NS |

Biomarker concentrations measured at week 6 are stratified based on the achievement of clinical and endoscopic remission during maintenance.

Table 4.

Associations of Week 14 Biomarkers With Maintenance Outcomes

| Median | IQR 25 to 75 | No. | Median | IQR 25 to 75 | No. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Remission | No Clinical Remission | ||||||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 7.1 | 4.6 to 7.5 | 7 | 8.0 | 6.7 to 8.7 | 5 | NS |

| α4β7, ng/mL | 20.3 | 15.4 to 23.5 | 7 | 6.0 | 4.7 to 7.9 | 6 | 0.013 |

| α4β7, change from baseline, ng/mL | 17.0 | 13.9 to 20.8 | 6 | 7.0 | 4.8 to 8.8 | 4 | 0.045 |

| MAdCAM-1, ng/mL | 3.3 | 2.1 to 4.2 | 7 | 2.5 | 2.0 to 3.5 | 6 | NS |

| SAA, mcg/mL | 10.0 | 2.6 to 15.1 | 7 | 25.7 | 13.9 to 29.4 | 6 | NS |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL | 598.0 | 424.0 to 713.5 | 7 | 784.0 | 731.0 to 887.3 | 6 | NS |

| s-VCAM, change from baseline, ng/mL | –58.0 | –125.8 to –6.8 | 6 | –127.5 | –168.3 to –77.0 | 4 | NS |

| CRP, mcg/mL | 4.9 | 2.8 to 17.2 | 7 | 5.0 | 3.8 to 10.4 | 6 | NS |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL | 330.0 | 301.5 to 445.5 | 7 | 371.0 | 354.3 to 506.3 | 6 | NS |

| Endoscopic Remission | No Endoscopic Remission | ||||||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 6.9 | 3.9 to 7.5 | 10 | 5.3 | 2.5 to 12.3 | 4 | NS |

| α4β7, ng/mL | 15.4 | 5.4 to 21.8 | 10 | 6.1 | 5.9 to 10.8 | 5 | NS |

| α4β7, change from baseline, ng/mL | 13.7 | 4.1 to 19.4 | 9 | 8.3 | 7.0 to 9.3 | 3 | NS |

| MAdCAM-1, ng/mL | 2.7 | 2.0 to 4.4 | 10 | 2.9 | 2.0 to 3.7 | 5 | NS |

| SAA, mcg/mL | 6.4 | 2.1 to 17.1 | 10 | 23.9 | 23.1 to 29.7 | 5 | 0.050 |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL | 589.1 | 458.0 to 760.3 | 10 | 746.0 | 726.0 to 909.0 | 5 | 0.050 |

| s-VCAM, change from baseline, ng/mL | –136.0 | –182.0 to –21.0 | 9 | 1.0 | –51.0 to 20.0 | 3 | NS |

| CRP, mcg/mL | 4.5 | 1.1 to 13.7 | 10 | 8.1 | 5.0 to 12.2 | 5 | NS |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL | 316.5 | 299.3 to 383.5 | 10 | 551.0 | 372.0 to 566.0 | 5 | 0.020 |

Biomarker concentrations measured at week 14 are stratified based on the achievement of clinical and endoscopic remission during maintenance.

Table 5.

Associations of Week 26 Biomarkers With Maintenance Outcomes

| Median | IQR 25 to 75 | No. | Median | IQR 25 to 75 | No. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Remission | No Clinical Remission | ||||||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 3.8 | 2.3 to 5.9 | 8 | 9.1 | 4.6 to 18.6 | 8 | NS |

| α4β7, ng/mL | 14.1 | 10.9 to 14.9 | 9 | 8.6 | 5.2 to 10.3 | 10 | 0.050 |

| α4β7, change from baseline, ng/mL | 13.2 | 10.4 to 13.9 | 5 | 4.4 | 2.2 to 5.5 | 3 | 0.053 |

| MAdCAM-1, ng/mL | 2.0 | 2.0 to 2.1 | 8 | 2.5 | 2.0 to 4.4 | 10 | NS |

| SAA, mcg/mL | 2.6 | 1.1 to 7.2 | 8 | 6.8 | 1.6 to 26.2 | 10 | NS |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL | 471.8 | 457.3 to 666.3 | 8 | 633.7 | 513.1 to 990.6 | 10 | NS |

| s-VCAM, change from baseline, ng/mL | –84.2 | –118.8 to 38.4 | 5 | 182.7 | 170.6 to 213.4 | 3 | 0.025 |

| CRP, mcg/mL | 1.1 | 0.6 to 6.5 | 9 | 3.6 | 2.1 to 10.5 | 10 | NS |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL | 360.9 | 315.3 to 373.3 | 8 | 363.5 | 299.3 to 924.2 | 10 | NS |

| Endoscopic Remission | No Endoscopic Remission | ||||||

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 3.8 | 2.5 to 8.6 | 10 | 9.1 | 5.8 to 17.3 | 6 | NS |

| α4β7, ng/mL | 11.1 | 8.6 to 14.5 | 12 | 8.3 | 5.8 to 10.0 | 7 | NS |

| α4β7, change from baseline, ng/mL | 13.2 | 10.4 to 13.9 | 5 | 4.4 | 2.2 to 5.5 | 3 | 0.053 |

| MAdCAM-1, ng/mL | 2.0 | 2.0 to 2.5 | 11 | 2.1 | 2.0 to 5.8 | 7 | NS |

| SAA, mcg/mL | 2.6 | 1.1 to 5.4 | 11 | 25.4 | 5.1 to 31.4 | 7 | NS |

| sVCAM-1, ng/mL | 478.1 | 457.2 to 626.1 | 11 | 690.4 | 579.3 to 1129.0 | 7 | NS |

| s-VCAM, change from baseline, ng/mL | –84.2 | –118.8 to 38.4 | 5 | 182.7 | 170.6 to 213.4 | 3 | 0.025 |

| CRP, mcg/mL | 2.2 | 0.8 to 4.7 | 12 | 7.1 | 1.8 to 13.0 | 7 | NS |

| sICAM-1, ng/mL | 359.4 | 304.0 to 371.6 | 11 | 412.8 | 311.5 to 1095.9 | 7 | NS |

Biomarker concentrations measured at ≥week 26 are stratified based on the achievement of clinical and endoscopic remission during maintenance.

Individual median baseline biomarker concentrations (s-TNF, s-α4β7, s-MAdCAM-1, CRP, s-AA, s-ICAM-1, s-VCAM-1) were not significantly different between groups for any outcomes.

TNF Concentrations

In all treated patients with baseline biomarkers measured, s-TNF concentrations significantly decreased from 9.1 pg/mL (n = 17) at baseline to 3.8 pg/mL at week 26 (n = 8, P = 0.04). Compared with baseline values, s-TNF concentrations were numerically lower at other time points (P = NS).

Using a linear mixed-effects model, s-TNF concentrations were found to decline more rapidly in endoscopic remitters (P = 0.052). However, this did not achieve significance.

Analysis at individual time points demonstrated significantly lower s-TNF concentrations (IQR) at week 2 (6.7 [2.5–8.8] vs 17.8 [12.1–24.5] pg/mL; P = 0.038) and week 6 (3.9 [2.3–6.4] vs 15.6 [11.5–22.3] pg/mL; P = 0.005) in endoscopic remitters.

s-α4β7 Concentrations

In all treated patients with baseline s-α4β7 measured (1.3 ng/mL, n = 18), concentrations significantly increased at week 2 (14.1 ng/mL, n = 11; P < 0.001), week 6 (11.4 ng/mL, n = 13; P < 0.001), week 14 (12.7 ng/mL, n = 13; P < 0.001), and week 26 (9.9 ng/mL, n = 8; P = 0.002) compared with baseline.

When analyzing (s)-α4β7 concentrations, a significant interaction between time and clinical remission (P = 0.044) was found. (s)-α4β7 increased more rapidly in clinical remitters. A similar trend was found for endoscopic remitters (P = 0.07).

Analysis at individual time points demonstrated that week 14 s-α4β7 concentrations (IQR) were significantly higher in clinical remitters (20.3 [15.4–23.5] vs 6.0 [4.7–7.9] ng/mL; P = 0.013). Furthermore, greater median increases in s-α4β7 concentrations from baseline to week 14 (IQR) were associated with clinical remission (17.0 [13.9–20.8] vs 7.0 [4.8–8.8] ng/mL; P = 0.045). At ≥week 26, significantly higher s-α4β7 concentrations were observed in clinical remitters (14.1 [10.9–14.9] vs 8.6 [5.2–10.3] ng/mL; P = 0.050). Furthermore, a trend toward greater median increases in s-α4β7 concentrations from baseline to week 26 was observed for clinical remitters and for endoscopic remitters (13.2 [10.4–13.9] vs 4.4 [2.2–5.5] ng/mL; P = 0.053).

s-MAdCAM-1 Concentrations

In all treated patients with baseline s-MAdCAM-1 measured, compared with baseline (22.3 ng/mL, n = 18), concentrations significantly decreased at week 2 (6.7 ng/mL, n = 11; P < 0.001), week 6 (3.4 ng/mL, n = 13; P < 0.001), week 14 (3.6 ng/mL, n = 13; P < 0.001), and week 26 (7.3 ng/mL, n = 7; P = 0.004).

When analyzing s-MAdCAM-1 concentrations, significant interactions between time and clinical remission (P = 0.006) and between time and endoscopic remission (P = 0.005) were identified. s-MAdCAM-1 declined more rapidly in both clinical and endoscopic remitters compared with nonremitters. However, at each time point, s-MAdCAM-1 concentrations in remitters vs nonremitters were not associated with outcomes.

s-AA Concentrations

S-AA concentrations significantly decreased from baseline (45.5 mcg/mL, n = 18) to week 14 (3.6 mcg/mL, n = 13; P = 0.025), and a downward trend was observed through week 26 (2.3 mcg/mL, n = 8; P = 0.1).

Significant interactions between time and clinical remission or endoscopic remission with s-AA were not found. Comparison between endoscopic remitters and nonremitters at individual time points demonstrated that week 14 s-AA concentrations (IQR) were significantly lower in endoscopic remitters (6.4 [2.1–17.1] vs 23.9 [23.1–29.7] mcg/mL; P = 0.05).

s-VCAM-1 Concentrations

In all treated patients, s-VCAM-1 significantly decreased from baseline (719.3 ng/mL, n = 18) to week 6 (637.8 ng/mL, n = 13; P = 0.002) and week 14 (622.5 ng/mL, n = 13; P = 0.003), but these changes did not persist at week 26 (695.0 ng/mL, n = 8; P = NS).

When analyzing s-VCAM-1 concentrations, there were significant interactions between time and clinical remission (P = 0.001) and endoscopic remission (P < 0.001). s-VCAM-1 declined more rapidly in clinical and endoscopic remitters.

Week 14 s-VCAM-1 concentrations (IQR) were significantly lower in endoscopic remitters (589.1 [458.0–760.3] vs 746.0 [726.0–909.0] ng/mL; P = 0.05). Regarding changes at week 26 as compared with baseline, median s-VCAM-1 concentrations decreased in clinical and endoscopic remitters (–84.2 [–118.8 to 38.4] vs 182.7 [170.6 to 213.4] ng/mL; P = 0.025), whereas s-VCAM-1 increased in nonremitters.

s-ICAM-1 Concentrations

In all treated patients with baseline biomarkers measured, s-ICAM-1 did not significantly change as compared with baseline. However, a significant interaction between time and endoscopic remission (P = 0.014) with s-ICAM-1 was found.

At individual time points, lower week 2 and week 14 s-ICAM-1 concentrations (IQR) were associated with endoscopic remission (385.9 [347.8–434.4] vs 508.6 [443–693.9] ng/mL; P = 0.042; and 316.5 [299.3–383.5] vs 551.0 [372.0–566.0] ng/mL; P = 0.020; respectively).

CRP Concentrations

In all treated patients with baseline biomarkers measured, CRP did not significantly change from baseline at any time point. There were no significant interactions between time and clinical remission (P = 0.44) or endoscopic remission (P = 0.75) with CRP. At individual time points, lower median CRP at week 2 was associated with endoscopic remission (P = 0.017), but not at other time points.

Correlations Between Biomarkers and Vedolizumab Concentration

Significant correlations between individual biomarker and vedolizumab concentrations were not consistently observed (Supplementary Table 3). TNF concentrations did not correlate with s-α4β7, s-VCAM-1, or s-ICAM-1 (Supplementary Table 4).

Relationship Between Corticosteroid Use and Biomarker Concentrations

Median baseline s-MAdCAM-1 concentrations were higher in patients with a corticosteroid requirement at baseline. Trends toward lower baseline s-TNF and s-α4β7 concentrations were seen in patients requiring corticosteroids at baseline. However, biomarker concentrations were not different between those requiring corticosteroids at week 26 and those not requiring corticosteroids at that time (Supplementary Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates the association between serum biomarkers with prospectively scored outcomes during maintenance vedolizumab therapy in UC patients.

The present study uniquely analyzes s-α4β7 profile changes during vedolizumab therapy in all treated patients and describes differences between remitters and nonremitters. s-α4β7 concentrations increased by week 2 and remained elevated, plateauing at weeks 6, 14, and 26. s-α4β7 increased more rapidly and was preferentially higher at individual time points in remitters. Notably, corticosteroid use and s-TNF concentrations did not affect s-α4β7 concentrations. Total s-α4β7 measurements used a sandwich ELISA that utilizes a distinct binding site from vedolizumab. This allows for detection of α4β7 that is both bound and not bound to vedolizumab. Thus, this may represent a convenient surrogate for α4β7 expression on lymphocytes in patients receiving vedolizumab therapy. This study’s findings are consistent with the current literature. An increase in α4β7 expression on lymphocytes during vedolizumab therapy has been correlated with symptom reduction.18 As increases in circulating lymphocytes have been shown with vedolizumab therapy31 and α4β7 mediates lymphocyte trafficking to the gut,23 total α4β7 (both vedolizumab-bound and unbound) is expected to increase. This may be related to reduction in gut trafficking with subsequent rise in serum concentrations or a prolonged half-life of circulating lymphocytes bound to vedolizumab.23 In a study with 11 vedolizumab-treated UC patients, pretreatment peripheral surface α4β7 expression on lymphocytes measured by flow cytometry was higher in clinical responders. Furthermore, responders had fewer memory T cells with unbound transmembrane α4β7.17 Another study of 17 vedolizumab-treated UC patients demonstrated associations between peripheral blood T-cell expression of α4β7 and clinical response.18

S-VCAM-1 decreased consistently at each individual time point after week 6, and although a significant difference was not observed at week 26, there was a smaller sample size at this time point. Consistent with these findings, s-VCAM-1 concentrations declined more rapidly in remitters compared with nonremitters. Furthermore, remitters had consistently greater reductions in s-VCAM-1 maintenance concentrations compared with baseline. Although s-ICAM was inconsistently lower at certain individual time points in remitters, concentrations declined more rapidly in remitters. Inconsistencies of data at individual time points may be accounted for by sample size considerations; thus the linear mixed-effects model better accounted for rates of change in biomarker concentrations over time in each group. Furthermore, later changes in s-VCAM-1 concentrations may be related to the time required for adaptive changes to occur. Vedolizumab specifically inhibits adhesion of α4β7+ cells to MAdCAM-1 without inhibiting adhesion of α4β1 to VCAM-1, which has been implicated in gastrointestinal inflammation.1, 31 Transmembrane ICAM-1 in the gut promotes β2 integrin–mediated leukocyte adhesion.32 Thus, this study’s findings suggest that α4β7 blockade may be insufficient for certain patients who have persistently elevated CAMs and may require α4β1, αEβ7, or β2 integrin blockade to inhibit leukocyte adherence. Alternatively, patients with elevated s-VCAM-1 or s-ICAM-1 may require medications with alternate mechanisms of action that do not target leukocyte trafficking. The concept of a compensatory adhesion molecule expression in the setting of α4β7 blockade is indirectly supported by the compensatory rise in CD4+ T-cell expression of α4β1+ that was associated with negative outcomes in vedolizumab-treated UC patients.18 This concept has further mechanistic support in CD patients.33

Serum s-VCAM-1 and s-ICAM-1 are both induced by TNF,31, 34, 35 and these relationships are independent of transmembrane intestinal CAMs.36, 37 Furthermore, previous studies have implicated various effects of corticosteroids used on CAMs.34, 35 Thus, relationships between CAMs with s-TNF and corticosteroids were explored. Lower s-VCAM-1 and s-ICAM-1 concentrations in remitters were independent of s-TNF concentrations or corticosteroid use. This is consistent with the existing literature.34, 35

Both s-TNF and s-AA decreased in the entire vedolizumab-treated cohort, but only consistently trended downward after week 6 and achieved significance during maintenance. TNF (inflammatory mediator) and s-AA (acute phase reactant) may represent a patient’s inflammatory burden. As remission is often only achieved after induction therapy, it is not surprising that these biomarkers of inflammatory burden only reduced later in the treatment course. Interestingly, although a more rapid decline in s-TNF was observed in endoscopic remitters, this was not seen with s-AA. This is consistent with the notion that vedolizumab does not alter acute phase reactants, such as CRP,3, 4, 38 differentially based on outcome and implies that alternative inflammatory mediators such as s-TNF may be useful surrogate biomarkers.

Concentrations of s-MAdCAM-1 decreased during the course of vedolizumab therapy in all patients and declined more rapidly in remitters. Notably, s-MAdCAM-1 concentrations were not consistently associated with corticosteroid use. Based on flow cytometry, vedolizumab administration has consistently been shown to completely inhibit MAdCAM-1 binding to α4β7 in UC patients.39, 40 A recent retrospective study in CD and UC patients found that undetectable concentrations of s-MAdCAM-1 during maintenance vedolizumab therapy were associated with clinical remission. In a subset of patients who were followed longitudinally, s-MAdCAM-1 concentrations decreased in all patients, but baseline s-MAdCAM-1 concentrations were not associated with outcomes.41 Our study shows consistent findings but describes a more rapid decline in s-MAdCAM-1 in remitters using linear mixed-effects modeling.

Vedolizumab concentrations were not associated with outcomes. However, this finding is limited by sample size, early trends were observed, and robust existing data support an exposure–response relationship.10–14 Furthermore, the lack of correlation between biomarkers and vedolizumab concentrations suggests that the associations of biomarkers with outcomes are independent of drug concentrations for the studied doses of vedolizumab.

Study limitations include a small sample size with missing data at different time points. Though the proportion of α4β7 that was not bound to vedolizumab was not quantified, it is well described that α4β7 receptor is fully saturated with all doses of vedolizumab but that this does not correlate with outcomes.9 We postulate that various biomarkers from the serum may be easily measurable surrogates for their cellular or transmembrane expression, but further investigation is necessary. Outcome rates were higher than those reported in clinical trials2 but were similar to results reported in real-world cohorts.42 Higher remission rates may be influenced by the use of PGA scoring. Although endoscopies were prospectively scored, they were not centrally read. In addition, patients may have persisted on therapy with dose escalation due to lack of alternative therapies during the study. Lastly, although tissue biomarker concentrations were not measured in this study, this information may provide valuable mechanistic insight into subsequent studies.

This study reports the association of serum biomarkers with outcomes in vedolizumab-treated UC patients. s-α4β7, s-TNF, s-MAdCAM-1, and s-AA significantly changed with vedolizumab therapy by week 26 compared with baseline. s-α4β7 increased, whereas s-TNF, s-MAdCAM-1, s-ICAM-1, and s-VCAM-1 declined, more rapidly in remitters. During induction time points, s-TNF concentrations were lower in remitters. During maintenance time points, s-α4β7 was consistently higher and s-VCAM-1 was consistently lower in remitters. Further investigation is needed to develop prediction models and determine if alternative treatment strategies based on biomarkers would improve outcomes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Inflammatory Bowel Diseases online.

Conflicts of interest: R.B.: no actual or potential conflicts of interest. P.S.D.: has received research support, consulting fees, and honoraria from Takeda; research support from Pfizer; consulting fees from Janssen; research support from Prometheus. N.V.C.: consulting fees from Janssen and Takeda. E.E.: speakers bureau for Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Prometheus. K.H., E.W., and A.J. are employees of Prometheus Laboratories Inc. J.P.: no actual or potential conflicts of interest. A.M.: no actual or potential conflicts of interest. J.N.: no actual or potential conflicts of interest. S.S.: has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Pfizer, Takeda, and AMAG Pharmaceuticals. J.T.C.: no actual or potential conflicts of interest. J.R.N.: no actual or potential conflicts of interest. W.J.S.: consulting fees from Abbvie, Akros Pharma, Allergan, Ambrx Inc., Amgen, Ardelyx, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Atlantic Pharmaceuticals, Avaxia, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Conatus, Cosmo Technologies, Escalier Biosciences, Ferring, Ferring Research Institute, Forward Pharma, Galapagos, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Immune Pharmaceuticals, Index Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, Lilly, Medimmune, Mesoblast, Miraca Life Sciences, Nivalis Therapeutics, Novartis, Nutrition Science Partners, Oppilan Pharma, Otsuka, Palatin, Paul Hastings, Pfizer, Precision IBD, Progenity, Prometheus Laboratories, Qu Biologics, Regeneron, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Robarts Clinical Trials (owned by Health Academic Research Trust or HART), Salix, Seattle Genetics, Seres Therapeutics, Shire, Sigmoid Biotechnologies, Takeda, Theradiag, Theravance, Tigenix, Tillotts Pharma, UCB Pharma, Vascular Biogenics, Vivelix; research grants from Atlantic Healthcare Limited, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, Lilly, Celgene/Receptos; payments for lectures/speakers bureau from Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda; and holds stock/stock options in Escalier Biosciences, Oppilan Pharma, Precision IBD, Progenity, Ritter Pharmaceuticals. B.S.B.: research grants from Takeda and Janssen; has consulted for Abbvie and Prometheus Laboratories; supported by a Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award and UCSD KL2 (1KL2TR001444).

Supported by: Vedolizumab trough concentrations, biomarkers, and antivedolizumab antibody concentrations were analyzed with an assay provided by Prometheus Laboratories Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). No other financial support was provided for this study. The UC San Diego Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute is partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant UL1TR001442 of Clinical and Translational Science Awards funding. CTSA consortium is funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions: planning and conducting the study (R.B., P.D., N.V.C., K.H., E.W., A.J., J.N., J.R.N., W.J.S., B.S.B.), data collection (R.B., P.D., E.E., K.H., E.W., A.J., J.N., S.S., W.J.S., B.S.B.), test interpretation (R.B., A.J., K.H., J.P., W.J.S., B.S.B.), interpreting data (R.B., N.V.C., J.T.C., K.H., A.J., J.P., J.R.N., W.J.S., B.S.B.), drafting the manuscript (all authors). Guarantor of the article: Brigid Boland.

REFERENCES

- 1. Soler D, Chapman T, Yang LL, et al. The binding specificity and selective antagonism of vedolizumab, an anti-alpha4beta7 integrin therapeutic antibody in development for inflammatory bowel diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:864–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. ; GEMINI 1 Study Group Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. ; GEMINI 2 Study Group Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sands BE, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Effects of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease in whom tumor necrosis factor antagonist treatment failed. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618–627.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mosli MH, MacDonald JK, Bickston SJ, et al. Vedolizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1151–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wyant T, Leach T, Sankoh S, et al. Vedolizumab affects antibody responses to immunisation selectively in the gastrointestinal tract: randomised controlled trial results. Gut. 2015;64:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wyant T, Yang L, Fedyk E.. In vitro assessment of the effects of vedolizumab binding on peripheral blood lymphocytes. MAbs. 2013;5:842–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Milch C, Wyant T, Xu J, et al. Vedolizumab, a monoclonal antibody to the gut homing α4β7 integrin, does not affect cerebrospinal fluid T-lymphocyte immunophenotype. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;264:123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ungar B, Kopylov U, Yavzori M, et al. Association of vedolizumab level, anti-drug antibodies, and α4β7 occupancy with response in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:697–705.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosario M, French JL, Dirks NL, et al. Exposure-efficacy relationships for vedolizumab induction therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:921–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maria R, Brihad A, Serap S, et al. O-003 relationship between vedolizumab pharmacokinetics and endoscopic outcomes of patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(suppl_1):S1–S3.25834857 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williet N, Boschetti G, Fovet M, et al. Association between low trough levels of vedolizumab during induction therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases and need for additional doses within 6 months. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1750–1757.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yarur A, Bruss A, Jain A, et al. DOP020 higher vedolizumab levels are associated with deep remission in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis on maintenance therapy with vedolizumab. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(suppl_1):S38. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yacoub W, Williet N, Pouillon L, et al. Early vedolizumab trough levels predict mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre prospective observational study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamann A, Andrew DP, Jablonski-Westrich D, et al. Role of alpha 4-integrins in lymphocyte homing to mucosal tissues in vivo. J Immunol. 1994;152:3282–3293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. von Andrian UH, Engelhardt B.. Alpha4 integrins as therapeutic targets in autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boden EK, Shows DM, Chiorean MV, et al. Identification of candidate biomarkers associated with response to vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:2419–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fuchs F, Schillinger D, Atreya R, et al. Clinical response to vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis patients is associated with changes in integrin expression profiles. Front Immunol. 2017;8:764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Connor EM, Eppihimer MJ, Morise Z, et al. Expression of mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) in acute and chronic inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sikorski EE, Hallmann R, Berg EL, et al. The Peyer’s patch high endothelial receptor for lymphocytes, the mucosal vascular addressin, is induced on a murine endothelial cell line by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IL-1. J Immunol. 1993;151:5239–5250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leung E, Lehnert KB, Kanwar JR, et al. Bioassay detects soluble MAdCAM-1 in body fluids. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vermeire S, Sandborn WJ, Danese S, et al. Anti-MAdCAM antibody (PF-00547659) for ulcerative colitis (TURANDOT): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Soler D, Chapman T, Yang LL, et al. The binding specificity and selective antagonism of vedolizumab, an anti-alpha4beta7 integrin therapeutic antibody in development for inflammatory bowel diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:864–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patel RT, Pall AA, Adu D, et al. Circulating soluble adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:1037–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burns RC, Rivera-Nieves J, Moskaluk CA, et al. Antibody blockade of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 ameliorates inflammation in the SAMP-1/Yit adoptive transfer model of Crohn’s disease in mice. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1428–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Souza HS, Elia CC, Spencer J, et al. Expression of lymphocyte-endothelial receptor-ligand pairs, alpha4beta7/MAdCAM-1 and OX40/OX40 ligand in the colon and jejunum of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1999;45:856–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yarur AJ, Quintero MA, Jain A, et al. Serum amyloid A as a surrogate marker for mucosal and histologic inflammation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19(Suppl A):5A–36A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Podolsky DK, Lobb R, King N, et al. Attenuation of colitis in the cotton-top tamarin by anti-alpha 4 integrin monoclonal antibody. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Albelda SM, Smith CW, Ward PA.. Adhesion molecules and inflammatory injury. Faseb J. 1994;8:504–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zundler S, Fischer A, Schillinger D, et al. The α4β1 homing pathway is essential for ileal homing of Crohn’s disease effector T cells in vivo. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones SC, Banks RE, Haidar A, et al. Adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1995;36:724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Göke M, Hoffmann JC, Evers J, et al. Elevated serum concentrations of soluble selectin and immunoglobulin type adhesion molecules in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giorelli M, De Blasi A, Defazio G, et al. Differential regulation of membrane bound and soluble ICAM 1 in human endothelium and blood mononuclear cells: effects of interferon beta-1a. Cell Commun Adhes. 2002;9:259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iwao M, Morisaki H, Morisaki T.. Single-nucleotide polymorphism g.1548G > A (E469K) in human ICAM-1 gene affects mRNA splicing pattern and TPA-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:729–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Amiot A, Grimaud JC, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. ; Observatory on Efficacy and of Vedolizumab in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group; Groupe d’Etude Therapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1593–1601.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Parikh A, Leach T, Wyant T, et al. Vedolizumab for the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled phase 2 dose-ranging study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1470–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rosario M, Wyant T, Leach T, et al. Vedolizumab pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and tolerability following administration of a single, ascending, intravenous dose to healthy volunteers. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36:913–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paul S, Williet N, Di Bernado T, et al. Soluble mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 and retinoic acid are potential tools for therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with vedolizumab: a proof of concept study. J Crohns Colitis. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kopylov U, Verstockt B, Biedermann L, et al. DOP001 effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in anti-TNF naïve patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre retrospective European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(supplement_1):S029–S030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.