Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Current literature reports that half of critically ill patients are continued on broad-spectrum antibiotics beyond 72 hours despite no confirmed infection. The purpose of this retrospective study was to identify the incidence of and risk factors for prolonged empiric antimicrobial therapy (PEAT) in adult neurocritical care (NCC) patients treated for pneumonia, hypothesizing that NCC patients will have a higher incidence of PEAT.

Methods:

This is a retrospective chart review of adult NCC patients treated for pneumonia. Antibiotic therapy was classified as restrictive, definitive, or PEAT based on culture results and timing of discontinuation or de-escalation.

Results:

A total of 95 patients (median age: 57 years; 28.4% female; admission diagnosis: 73.7% cerebrovascular, 10.5% neuromuscular, and 15.8% seizure-related) were included in this study. Overall, 59% of antibiotic regimens were considered PEAT, with vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam being most commonly prescribed. Median duration of therapy was 6.8 days, with shorter duration in patients with negative culture results compared to those with positive culture results (6.1 days [interquartile range, IQR 4.0-8.3] vs 7.2 days [IQR 5.8-10.3], P < .05). On multivariable analysis, elevated baseline white blood cell count, meeting Centers for Disease Control criteria for pneumonia, and negative bacterial culture were significantly associated with PEAT.

Conclusion:

The incidence of prolonged empiric antibiotic use was high in the NCC population. Patients are at particular risk for PEAT if they have negative cultures. All but one patient did not meet criteria for central fever, highlighting the challenges in identifying fever etiology in the NCC population.

Keywords: neurocritical care, prolonged empiric antibiotic therapy, pneumonia, culture negative, critical illness

Introduction

Infectious diseases can be challenging to manage in patients admitted to a neurocritical care unit (NCCU) due to difficulties in their diagnosis and treatment, as well as their increased risk of hospital-acquired infections (HAIs).1 Patients in the NCCU are at a higher risk of noninfectious fever, and there has been interest in developing models that can reliably differentiate between infectious versus noninfectious fevers.2 It has been estimated that the incidence of noninfectious fevers may be as high as 50%.1,2 Such a high incidence of noninfectious fevers presents challenges in identifying infectious fevers, potential infectious sources, and subsequently the decision to initiate empiric antibiotics. Previously, pneumonia has been reported as one of the highest occurring HAIs in the NCCU; thus, empiric antibiotic therapy is frequently targeted at a respiratory source.3

Past guidelines for hospital- and ventilator-acquired pneumonia have suggested that empiric antibiotic selection should be reassessed by 72 hours and should be discontinued if no infection is confirmed or if no specific pathogen is identified.4 More recent guidelines do not recommend a specific time point for de-escalation, however strongly support de-escalation or discontinuation of antibiotics upon the receipt of finalized culture results, which frequently occurs prior to 72 hours.5 These recommendations are based on the presumed relationship between inappropriate antibiotic use and avoidable side effects, drug resistance, and cost. Despite this, recent research has suggested that current practices in intensive care units (ICUs) do not align with current guideline recommendations regarding judicious antibiotic use. A secondary analysis of nosocomial infections in medical/surgical ICUs reported that 59% of patients were inappropriately continued on empiric antibiotics beyond 4 days.6 Similarly, in a more recent prospective snapshot study of all ICU types, 50.5% of patients were inappropriately continued on empiric antibiotics for longer than 3 days.7 While NCCU patients were included in the latter study, it did not evaluate this subpopulation specifically, nor did these studies address potential differences among various infectious syndromes.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the utilization of empiric antibiotics for the treatment of pneumonia (hospital-acquired, community-acquired, or ventilator-associated) in patients admitted to a NCCU. Our primary objective is to determine the incidence of prolonged empiric antibiotic therapy (PEAT) in the neurocritical care (NCC) patient population. Secondary objectives include (1) evaluating adherence to guideline-based recommendations regarding indication to treat, selection of empiric antibiotic, and length of treatment; (2) identifying the number of patients treated for an infectious fever that meet the criteria for central fever; and (3) determining the incidence of adverse effects such as nephrotoxicity and Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). We hypothesize that there is a high incidence of PEAT for the treatment of pneumonia in NCCU patients, particularly as it compares to previous reports across all ICUs.

Methods

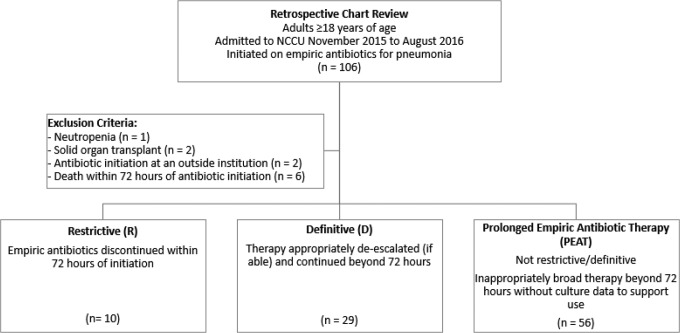

This is a retrospective chart review of all adult patients admitted to the NCCU at an 800-bed academic medical center in Baltimore, Maryland (Figure 1). Patients were included in this study if they were older than 18 years and were initiated on antibiotics for pneumonia between November 2015 and August 2016. Exclusion criteria included neutropenia, history of a solid organ transplant, patients who had antibiotics initiated at an outside hospital prior to admission to the NCCU, and patients who died or had care withdrawn within 72 hours of antibiotic initiation. This study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the institutional review board of University of Maryland.

Figure 1.

Study design. NCCU indicates neurocritical care unit.

Baseline data collected included age, sex, admitting diagnosis, comorbidities, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and duration of mechanical ventilation prior to antibiotic initiation. Clinical data collected included Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score (CPIS) criteria,8 the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) criteria for pneumonia,9 culture data, antibiotic data, white blood cell (WBC) count and temperature (body temperature as well as water temperature for those patients treated with the institutional normothermia protocols) on all days of antibiotic therapy, and the incidence of side effects including acute kidney injury and CDI.

For the primary objective of this study, antibiotic therapy was classified as restrictive, definitive, or PEAT. Restrictive antibiotic therapy was therapy that was discontinued prior to 72 hours postinitiation. Definitive antibiotic therapy was therapy that was appropriately de-escalated (if able) and continued beyond 72 hours postinitiation. The PEAT was therapy that did not meet the criteria for either restrictive or definitive therapy (ie, inappropriately broad therapy that was continued beyond 72 hours without culture data to support its use). Antibiotic classification was subsequently stratified by CPIS criteria, CDC criteria, and culture positivity to determine any differences between patients who did versus did not meet the respective criteria.

For the secondary objectives, patients were considered to have an indication to treat if they had a CPIS of >6 or if they met the CDC criteria for pneumonia. To identify patients who met the criteria for central fevers, the model proposed by Hocker and colleagues was used.2 For adverse effects, patients were identified as experiencing acute kidney injury if they met the RIFLE criteria for injury or failure.10 Any occurrence of CDI within the same hospital encounter but after the initiation of antibiotics was considered an adverse event. Incidence of central fever and adverse effects was compared between patients receiving antibiotics considered restrictive, definitive, and PEAT.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics for frequencies and ranges. To compare any differences between CPIS >6 and CPIS ≤6, CDC criteria (yes/no), and culture positive (yes/no), independent t test or Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables were performed. Multinomial logistic regression or logistic regression analyses were performed to adjust covariates and measure the association of the study objectives and indications for empiric treatment. Patient characteristics deemed to be significantly related to PEAT on univariate analysis were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model. Any missing data points were excluded from analyses. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York).

Results

A total of 106 patients were identified as having received antibiotics in the NCCU between November 2015 and August 2016 for the indication of a respiratory infection. After screening for exclusion criteria, 95 patients were included in this study. Baseline characteristics for the study population as a whole, as well as for our primary objective subgroups, are described in Table 1. The study population was largely male (71.6%) with an average age of 57 and an admission diagnosis was cerebrovascular in nature (73.7%). The average APACHE II score was 15.4, with a large majority of patients being mechanically ventilated at the time of antibiotic initiation (87.4%). All patients except for 1 had a respiratory culture. This patient’s culture data represent the one missing data point excluded from analysis. Among the subgroups, significant differences in radiographic findings and APACHE II existed between patients who did and did not meet CPIS criteria, as well as type of pneumonia between patients who did and did not have positive cultures.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.a,b

| Characteristics | Total (N = 95) | CPIS | P Value | CDC Criteria | P Value | Culture Positiveb | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >6 (n = 23) | ≤6 (n = 72) | Yes (n = 17) | No (n = 78) | Yes (n = 48) | No (n = 46) | |||||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 57.1 (15.7) | 57.8 (17.6) | 56.9 (15.2) | .81 | 56.9 (18.6) | 57.2 (15.1) | .96 | 54.9 (17.9) | 59.0 (12.9) | .20 |

| Gender, n (%) | .81 | 1.0 | .29 | |||||||

| Female | 27 (28.4) | 7 (30.4) | 20 (27.8) | 5 (29.4) | 22 (28.2) | 11 (22.9) | 15 (32.6) | |||

| Male | 68 (71.6) | 16 (69.6) | 52 (72.2) | 12 (70.6) | 56 (71.8) | 37 (77.1) | 31 (67.4) | |||

| Admission diagnosis, n (%) | .13 | .36 | .75 | |||||||

| Cerebrovascular | 70 (73.7) | 18 (78.3) | 52 (72.2) | 14 (82.3) | 56 (71.8) | 34 (70.8) | 35 (76.1) | |||

| SAH | 19 (27.1) | 6 (33.3) | 13 (25.0) | 5 (35.7) | 14 (25.0) | 9 (26.5) | 10 (28.6) | |||

| ICH | 23 (32.9) | 7 (38.9) | 16 (30.8) | 2 (14.3) | 21 (37.5) | 12 (35.3) | 11 (31.4) | |||

| Ischemic stroke | 21 (30.0) | 3 (16.7) | 18 (34.6) | 6 (42.9) | 15 (26.8) | 12 (35.3) | 8 (22.9) | |||

| Neuromuscular | 10 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 10 (13.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (12.8) | 5 (10.4) | 5 (10.9) | |||

| Seizure-related | 15 (15.8) | 5 (21.7) | 10 (13.9) | 3 (17.7) | 12 (15.4) | 9 (18.8) | 6 (13.0) | |||

| Select comorbidities, n (%) | .94 | .64 | .057 | |||||||

| Asthma | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.3) | |||

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 10 (10.5) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (6.9) | 4 (23.5) | 6 (7.7) | 9 (18.8) | 1 (2.2) | |||

| COPD | 9 (9.5) | 2 (8.7) | 7 (9.7) | 2 (11.8) | 7 (9.0) | 7 (14.6) | 2 (4.3) | |||

| T2DM | 31 (32.6) | 8 (34.8) | 23 (31.9) | 5 (29.4) | 26 (33.3) | 12 (25.0) | 18 (39.1) | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 25 (26.3) | 8 (34.8) | 17 (23.6) | 6 (35.3) | 19 (24.4) | 14 (29.2) | 11 (23.9) | |||

| Hypertension | 59 (62.1) | 16 (69.6) | 43 (59.7) | 12 (70.6) | 47 (60.3) | 28 (58.3) | 30 (65.2) | |||

| Restrictive lung disease | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | |||

| History of ischemic stroke/TIA | 13 (13.7) | 4 (17.4) | 9 (12.5) | 4 (23.5) | 9 (11.5) | 5 (10.4) | 8 (17.4) | |||

| History of SAH | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | |||

| Tobacco use | 17 (17.9) | 5 (21.7) | 12 (16.7) | 4 (23.5) | 13 (16.7) | 8 (16.7) | 9 (19.6) | |||

| Baseline temperature, mean (SD) | 37.6 (0.9) | 37.5 (1.5) | 37.6 (0.7) | .66 | 37.9 (1.0) | 37.5 (0.9) | .16 | 37.4 (1.0) | 37.8 (0.9) | .11 |

| Baseline WBC, mean (SD) | 12.7 (5.2) | 12.6 (4.5) | 12.8 (5.4) | .87 | 13.4 (4.1) | 12.6 (5.4) | .54 | 12.4 (5.0) | 13.1 (5.5) | .55 |

| Radiograph findings, n (%) | .0069c | .12 | .19 | |||||||

| Diffuse/patchy | 18 (19.0) | 2 (8.7) | 16 (22.2) | 3 (17.7) | 15 (19.2) | 6 (12.5) | 12 (26.1) | |||

| Localized | 63 (66.3) | 21 (91.3) | 42 (58.3) | 14 (82.4) | 49 (62.8) | 33 (68.8) | 29 (63.0) | |||

| No infiltrate | 14 (14.7) | 0 (0) | 14 (19.4) | 0 (0) | 14 (18.0) | 9 (18.8) | 5 (10.9) | |||

| APACHE II score, mean (SD) | 15.4 (6.2) | 18.7 (7.0) | 14.4 (5.6) | .0033c | 15.8 (5.2) | 15.4 (6.4) | .78 | 16.3 (6.4) | 14.6 (6.0) | .18 |

| Mechanically ventilated, n (%) | .72 | .69 | .12 | |||||||

| Yes | 83 (87.4) | 21 (91.3) | 62 (86.1) | 16 (94.1) | 67 (85.9) | 45 (93.8) | 38 (82.6) | |||

| No | 12 (12.6) | 2 (8.7) | 10 (13.9) | 1 (5.9) | 11 (14.1) | 3 (6.3) | 8 (17.4) | |||

| Type of pneumonia, n (%) | .93 | 1.0 | .0072c | |||||||

| VAP | 61 (64.2) | 14 (60.9) | 47 (65.3) | 11 (64.7) | 50 (64.1) | 38 (79.2) | 23 (50.0) | |||

| HAP | 26 (27.4) | 7 (30.4) | 19 (26.4) | 5 (29.4) | 21 (26.9) | 9 (18.8) | 17 (37.0) | |||

| CAP | 8 (8.4) | 2 (8.7) | 6 (8.3) | 1 (5.9) | 7 (9.0) | 1 (2.1) | 6 (13.0) | |||

| Culture type, n (%) | .47 | .38 | .38 | |||||||

| BAL | 64 (67.4) | 18 (78.3) | 46 (63.9) | 14 (82.4) | 50 (64.1) | 35 (72.9) | 29 (63.0) | |||

| Sputum | 30 (31.6) | 5 (21.7) | 25 (34.7) | 3 (17.6) | 27 (34.6) | 13 (27.1) | 17 (37.0) | |||

| None | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

Abbreviations: APACHE II, Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; CDC, Centers for Disease Control; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPIS, Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; TIA, transient ischemic attack; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; WBC, white blood count.

a Data are presented as mean (SD) for continuous and n (column %) for categorical variables.

b Frequency missing = 1.

c Statistically significant (P < .05).

Overall, 58.9% of patients were treated with empiric antibiotic regimens considered to be PEAT, 30.5% considered to be definitive, and 10.5% considered to be restrictive (Table 2). The multivariate analysis was performed using the following patient characteristics: baseline WBC, admission diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage, having met the CDC criteria for pneumonia, and culture positivity. Upon analysis, elevated baseline WBC count (>12,000) (odds ratio [OR], 1.177; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.040-1.332) and positive CDC criteria for pneumonia (OR, 3.206; 95% CI, 1.041-9.872) were more likely to be associated with PEAT, whereas culture positivity (OR, 3.206; 95% CI, 0.023-0.222) was less likely to be associated with PEAT. A statistically significant difference in the incidence of PEAT was seen in patients who had negative cultures compared to those who had positive cultures (84.8% vs 35.4%, respectively, P < .0001). By definition, there were no antibiotic regimens considered to be definitive therapy in the culture-negative group, therefore resulting in a statistically significant difference in the incidence of definitive and restrictive therapy. No statistical difference was seen in the incidence of antibiotics that were definitive, restrictive, or PEAT when comparing those who did and did not meet CPIS criteria or CDC criteria for pneumonia.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Antibiotic Use.a

| Parameters | Total (N = 95) | CPIS score (n = 95) | CDC criteria (n = 95) | Culture positive (n = 94) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >6 (n = 72) | ≤6 (n = 23) | Yes (n = 78) | No (n = 17) | Yes (n = 46) | No (n = 48) | ||

| Selection of empiric antibiotics | |||||||

| Ampicillin–sulbactam | 9 (9.5) | 7 (9.7) | 2 (8.7) | 8 (10.2) | 1 (5.9) | 6 (13.0) | 2 (4.2) |

| Cefepime | 9 (9.5) | 8 (11.1) | 1 (4.3) | 9 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (13.0) | 3 (6.3) |

| Ceftriaxone | 8 (8.4) | 7 (9.7) | 1 (4.3) | 7 (9.0) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (6.5) | 5 (10.4) |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 54 (56.8) | 42 (58.3) | 12 (52.2) | 42 (53.8) | 12 (70.6) | 27 (58.7) | 27 (56.3) |

| Vancomycin | 56 (58.9) | 42 (58.3) | 14 (60.9) | 46 (59.0) | 10 (58.8) | 28 (60.9) | 28 (58.3) |

| Empiric antibiotic effectiveb | |||||||

| No | 6 (6.3) | 3 (4.2) | 3 (13.0) | 5 (6.4) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0)c | 6 (12.5)c |

| Yes | 71 (74.7) | 53 (73.6) | 18 (78.3) | 55 (70.5) | 16 (94.1) | 0 (0)c | 42 (87.5)c |

| N/A | 18 (18.9) | 16 (22.2) | 2 (8.7) | 18 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 46 (100.0)c | 0 (0)c |

| 72-Hour de-escalation | |||||||

| Therapy | |||||||

| Restrictive | 10 (10.5) | 8 (11.1) | 2 (8.7) | 9 (11.5) | 1 (5.9) | 7 (15.2)c | 2 (4.2)c |

| Definitive | 29 (30.5) | 20 (27.8) | 9 (39.1) | 23 (29.5) | 6 (35.3) | 0 (0)c | 29 (60.4)c |

| PEAT | 56 (58.9) | 44 (61.1) | 12 (52.2) | 46 (59.0) | 10 (58.8) | 39 (84.8)c | 17 (35.4)c |

| Length of empiric treatment in PEAT | |||||||

| Hours, median (IQR) | 106 (64-158) | 102 (68-166) | 116 (44-141) | 95 (56-162) | 125 (74-136) | 90 (56-160) | 124 (74-145) |

| Length of overall treatment | |||||||

| Days, median (IQR) | 6.8 (5.2-8.9) | 6.7 (4.7-8.5) | 7.2 (5.4-12.2) | 6.8 (4.9-9.0) | 6.9 (5.6-8.5) | 6.1 (4.0-8.3)d | 7.2 (5.8-10.3)d |

| Time to resolution of leukocytosis (days) | 2 (0-6) | 2 (0-6) | 2 (0-6) | 2 (0-8) | 3 (0-5) | 0 (0-4.5) | 3.5 (0-8) |

| Time to resolution of fever (days) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-8) | 3 (2-6) | 4.5 (2-7) | 3 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control; CPIS, clinical Pulmonary Infection Score; IQR, interquartile range; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PEAT, prolonged empiric antibiotic therapy.

a Data are presented as median (IQR) for continuous and n (column %) for categorical variables.

b Effective defined by having appropriate spectrum of activity against the bacteria grown in cultures.

c P < .0001, P values from Wilcoxon test for continuous and χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

d P < .05, P values from Wilcoxon test for continuous and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Regarding an initial indication to treat, 24.2% of patients met CPIS criteria and 36.8% of patients met CDC criteria for pneumonia. At 72 hours post-antibiotic initiation, 48.9% of patients were culture negative, and only 17.9% of patients met CDC criteria for pneumonia when also incorporating culture data. The most commonly prescribed antibiotics were vancomycin and piperacillin–tazobactam (58.9% and 56.8%, respectively; Table 2). Median overall treatment duration was 6.8 days (interquartile range, 5.2-8.9), with a statistically significant difference between patients who did versus did not have positive cultures (6.1 vs 7.2, P < .05).

Only 1 patient met the criteria for central fever, and this patient’s antibiotic regimen was considered PEAT (Table 3). Acute kidney injury occurred in 10.5% of patients, respectively, with similar incidence in the definitive and PEAT categories. No acute kidney injury was noted in patients receiving restrictive antibiotics. Only one case of CDI was noted, and this patient received a restrictive antibiotic regimen.

Table 3.

Incidence of Central Fever and Adverse Events by Therapy.a

| Total (N = 95) | Restrictive (n = 10) | Definitive (n = 29) | PEAT (n = 56) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central fever | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Adverse events | ||||

| Acute kidney injury | 10 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (13.8) | 6 (10.7) |

| Clostridium difficile infection | 1 (1.1) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

a Data are presented as n (%).

Discussion

Compared to what has been reported previously, the incidence of PEAT was similar to the original study by Aarts and colleagues evaluating medical/surgical ICUs but increased compared to the more recent study by Thomas and colleagues evaluating all types of ICUs.6,7 These studies did evaluate all antibiotics regardless of infectious source, which makes direct comparison of our results to these data difficult. Additionally, it may be more relevant to compare our data set to Thomas and colleagues due to the more recent push for antimicrobial stewardship by accrediting bodies such as the Joint Commission and payers like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.11,12 At the authors’ institution, an antimicrobial stewardship program exists that utilizes prospective audit with feedback. However, at the time these patients received care, the program was not yet actively involved with the NCCU.

Interestingly, patients who had negative respiratory cultures had a much higher incidence of PEAT than those with positive cultures, highlighting the difficulty providers face regarding antibiotic de-escalation in persistently febrile patients without positive cultures. Although culture-negative patients were treated with a statistically shorter duration of therapy, clinically they still received a 7-day course of antibiotics. Recently, a study evaluating ultrashort course of antibiotics for ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with minimal and stable ventilator settings found no difference in outcomes between patients receiving 1 to 3 days of antibiotics compared to those receiving >3 days.13 Given the large proportion of mechanically ventilated patients in the present study, it is possible that similar NCCUs may benefit from a model that utilizes daily ventilator settings as a tool for identifying patients who qualify for early antibiotic discontinuation.

Only 1 patient in this study met the criteria for central fevers as proposed by Hocker and colleagues.2 However, the extensively restrictive criteria used in this model are acknowledged. In the present study, many respiratory cultures grew what was deemed noninfectious normal respiratory flora, which excludes patients from being considered as having central fever according to the proposed model. The authors believe that a much higher percentage of patients in the present study were experiencing central fevers than is reported by the model by Hocker and colleagues.

A majority of the adverse events seen in this study were in patients receiving antibiotics longer than 72 hours, supporting the well-known theory that prolonged antibiotic use may be harmful to patients, particularly in those patients without a clear benefit for its prolonged use. This stresses the importance of limiting the number of patients receiving PEAT since the risk of adverse effects associated with prolonged use may outweigh the benefit in many of these patients.

It is important to note that new guidelines for the treatment of pneumonia were published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America in July 2016, so patients included in this study were largely treated under the older 2005 guidelines.4,5 As previously mentioned, one of the major differences in the 2016 guidelines is the removal of the 72-hour time point as the point of reevaluation of antibiotics—rather, antibiotics should be reevaluated upon finalization of cultures. As seen in our present study, PEAT was seen despite negative cultures at both 72-hour mark and upon finalization. It is unlikely that this change in recommendation by the 2016 guidelines will result in different practice patterns in the NCCU since the challenges of persistently febrile patients will still remain. Another major difference with the new guidelines is the removal of “healthcare-associated pneumonia.” Our providers largely use both guideline recommendations and institution antibiograms to guide empiric antibiotic selection, which may explain why many of the now-considered community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) patients were given broad-spectrum antibiotics such as piperacillin–tazobactam or vancomycin. Still, CAP patients represent only a small portion of NCCU patients, so this distinction is unlikely to change practice in these units. An additional difference in the 2016 guidelines is a much more detailed recommendation regarding the appropriate use of empiric vancomycin. According to the new guidelines, only 10% of hospital-acquired pneumonia is due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and therefore, MRSA coverage should not be empirically initiated in all patients. However, the 2016 guidelines do acknowledge that empiric initiation of vancomycin may be appropriate if an institution has Staphylococcus aureus resistance rates to methicillin that are higher than 10% to 20%. Based on criteria outlined by the 2016 guidelines, all of the patients receiving vancomycin were deemed appropriate based on our institution’s methicillin resistance rates alone. Despite the 2016 guideline recommendations, our institution has recently placed particular value on previous MRSA infection or current MRSA nasal swab results to determine the need for vancomycin empirically. Recent data have suggested that the MRSA nasal swab has a 99.4% negative predictive value and can be used to guide discontinuation or prevent initiation of MRSA-directed therapies.14 We predict that the use of vancomycin at our institution will decrease compared to what was seen in the present study, as a result of this most recent data.

There are many limitations to this study that should be acknowledged. It is a retrospective design and relied upon documentation in the electronic medical record, which may not be completely reflective of the clinical status of the patient. Additionally, this was a single-center study and prescribing patterns may be different at other institutions; however, we anticipate that other institutions face similar challenges in antibiotic de-escalation. A significant limitation of this study is that we did not account for concurrent coinfections, though we did only include patients who were specifically being treated for pneumonia. Lastly, only antibiotics given during the patient’s stay in the NCCU were evaluated. Antibiotics continued outside of the NCCU were not included, which may have resulted in an underestimation of total duration of therapy.

To conclude, the incidence of prolonged empiric antibiotic use was high in the NCC population, particularly as it relates to what has been previously reported across all ICUs (58.9% and 50.5%, respectively). Our data suggest that prolonged empiric antibiotic use beyond 72 hours is of particular concern in the subset of patients with negative cultures. All but one patient did not meet criteria for central fever, highlighting the challenges in identifying fever etiology in the NCC population. Additionally, patients who did not meet criteria for pneumonia based on CPIS or CDC criteria were still given 7 days of treatment. Culture-negative patients were given shorter durations of therapy compared to culture-positive patients but were still given close to the full treatment course for pneumonia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hyunuk Seung, M.S. for his assistance in the statistical analyses for this research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Ciera L. Patzke, PharmD  http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8566-4345

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8566-4345

References

- 1. O’Horo JC, Sampathkumar P. Infections in neurocritical care. Neurocrit Care. 2017;27(3):458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hocker SE, Tian L, Li G, Steckelberg JM, Mandrekar JN, Rabinstein AA. Indicators of central fever in the neurologic intensive care unit. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(12):1499–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dettenkofer M, Ebner W, Els T, et al. Surveillance of nosocomial infections in a neurology intensive care unit. J Neurol. 2001;248(11):959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):e61–e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aarts MA, Brun-Buisson C, Cook DJ, et al. Antibiotic management of suspected nosocomial ICU-acquired infection: does prolonged empiric therapy improve outcome? Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(8):1369–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thomas Z, Bandali F, Sankaranarayanan J, et al. A multicenter evaluation of prolonged empiric antibiotic therapy in adult ICUs in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(12):2527–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garrard CS, A’Court CD. The diagnosis of pneumonia in the critically III. Chest. 1995;108(2):17S–25S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control. Pneumonia (Ventilator-associated [VAP] and non-ventilator-associated Pneumonia [PNEU]) event. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/6pscvapcurrent.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2018.

- 10. Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, et al. Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the second international consensus conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8(4):R204–R212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Joint Commission. Approved: new antimicrobial stewardship standard. Joint Commission Perspectives. 2016;36(7):1–8. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/New_Antimicrobial_Stewardship_Standard.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS issues proposed rule that prohibits discrimination, reduces hospital-acquired conditions, and promotes antibiotic Stewardship in hospitals. 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-06-13.html. Accessed June 29, 2017.

- 13. Klompas M, Li L, Menchaca JT, et al. Ultra-short-course antibiotics for patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia but minimal and stable ventilator settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(7):870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chotiprasitsakul D, Tamma PD, Gadala A, Cosgrove SE. The role of negative methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus nasal surveillance swabs in predicting the need for empiric vancomycin therapy in intensive care unit patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(3):290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]