Abstract

Background:

Bacterial pneumonia is a major cause of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support. However, it is unknown whether the type of pneumonia, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) versus hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), should be considered when predicting outcomes for ARDS patients treated with ECMO.

Methods:

We divided a sample of adult patients receiving ECMO for acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by bacterial pneumonia between January 2012 and December 2016 into CAP (n = 21) and HAP (n = 35) groups and compared clinical and bacteriological characteristics and outcomes.

Results:

The median acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II and sequential organ failure assessment scores were 22 and 8, respectively, in the CAP and HAP groups. The most commonly identified organism in the CAP group was Streptococcus pneumonia (n = 12, 57.1%), while Acinectobacter baumanii was the most commonly identified in the HAP group (n = 13, 37.1%). However, the incidence of multidrug resistant bacteria was not different between groups (57.1% versus 74.3%, p = 0.125). Of the 56 patients in the study, 26 were successfully weaned from ECMO, and 20 were discharged from the hospital. There were no significant differences in ECMO weaning rate (47.6% versus 45.7%, p > 0.999) or survival to discharge rate (33.3% versus 37.1%, p > 0.999) between the two groups. The 30-day and 90-day mortality rates were also similar.

Conclusion:

Patients with CAP and HAP who received ECMO for respiratory support had similar characteristics and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, pneumonia

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening form of respiratory failure associated with a mortality rate of approximately 40–45%.1,2 As several studies have demonstrated the benefits of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in patients with ARDS who are unresponsive to conventional management, ECMO is emerging as a potential therapeutic modality, and its use in clinical practice is increasing.3–5 However, ECMO is still a complex and costly treatment that can be exposed to several significant complications. Therefore, efforts have been made to identify patients who are more likely to survive after ECMO support.

Bacterial pneumonia is a predominant etiology of acute respiratory failure requiring ECMO.5 Pneumonia is classified as community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) or hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP). CAP and HAP require different therapeutic approaches, because different causative pathogens are involved.6,7 Some studies suggest that CAP and HAP should be regarded as distinct clinical entities since they have different clinical courses.8,9

Although bacterial pneumonia is regarded as a favorable factor for survival after ECMO support,10 it is unknown whether type of pneumonia (CAP or HAP) should be considered when predicting outcomes for ARDS patients treated with ECMO. The objective of this study was to identify clinical, bacteriological, and treatment characteristics in pneumonia patients who received ECMO for respiratory support according to type of pneumonia and to compare clinical outcomes between groups.

Methods

Study design and sample

This observational study was conducted at Samsung Medical Center (a 1989-bed, university-affiliated, tertiary referral hospital in Seoul, South Korea) between January 2012 and December 2016. We included adult patients over 18 years of age who were diagnosed with ARDS caused by bacterial pneumonia and received ECMO for respiratory support during the study period. Patients under 18 years of age, in whom other pathogens (e.g. virus or fungus) were identified, who lacked microbial identification, or who were transferred from other hospitals after ECMO initiation were excluded from this study. Eligible patients were divided into two groups according to type of pneumonia, CAP or HAP. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (approval no: 2017-07-075), which waived the need for informed consent because of the retrospective observational nature of the study. All patient data were anonymized and de-identified before analysis.

Diagnosis and management of pneumonia ARDS

Pneumonia was diagnosed when we detected new radiographic infiltrates with at least two of the following clinical criteria: fever or hypothermia, new cough with or without sputum production, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, and altered breath sounds on auscultation.11 If a patient was clinically suspected or diagnosed with pneumonia, empirical antibiotic therapy was initiated according to standard guidelines.6,7 We classified pneumonia cases into two categories: CAP for pneumonia that occurred or developed outside of the hospital setting and HAP for pneumonia that occurred ⩾2 days after hospitalization and was not incubating at the time of hospital admission.6 According to the Berlin definition, ARDS was defined as follows: onset within 1 week of a known clinical insult or new or worsening respiratory symptoms; bilateral opacities not fully explained by effusions, lobar/lung collapse, or nodules; respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload and requiring objective assessment to exclude hydrostatic edema if no risk factor is present; and partial arterial oxygen concentration/inspired oxygen faction (PaO2/FiO2) ratio ⩽ 300 mmHg with positive end-expiratory pressure or continuous positive airway pressure ⩾ 5 cmH2O.1

Management of mechanical ventilation (MV) was performed according to the protocol proposed by the ARDS Network as much as possible.12,13 When patients could not maintain adequate oxygenation or carbon dioxide removal with MV, adjunctive therapies such as inhaled nitric oxide, prone positioning, and glucocorticosteroid therapy were also used at the discretion of the physician.

Initiation and management of ECMO

Patient selection, medical management, and settings of the MV and ECMO circuits followed institutional protocols that have been described previously.14 Patients with deteriorating hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 80 on FiO2 > 90%) or uncompensated hypercapnia (CO2 retention with pH < 7.20 despite plateau pressure > 30 cmH2O) under advanced mechanical ventilator support with or without adjunctive therapies were considered for ECMO support. The final decisions regarding ECMO initiation were made after consultation with a multidisciplinary ECMO team consisting of intensivists, pulmonologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons.

Pump blood flow and sweep gas flow rates were adjusted to maintain target oxygen saturation and carbon dioxide removal rate at all times. During ECMO support, pressure controlled ventilation mode was used for patients with FiO2 lower than 30%, respiratory rate lower than 10–12 per minute, positive end-expiratory airway pressure of 10 cmH2O, and peak inspiratory pressure of 20–25 cmH2O to achieve low tidal ventilation (< 5 ml/kg of predicted body weight) and prevent ventilator-induced lung injury. If patients were stable and tolerant of treatment, we changed the mode of MV to pressure support ventilation and subsequently adjusted ventilator settings for weaning. The possibility of weaning from ECMO was assessed daily, and trial off was performed to determine decannulation when arterial blood gas was maintained within the target range with a sweep gas flow of 1 l/min or less regardless of pump blood flow at acceptable ventilator settings. Patients who maintained adequate gas exchange without sweep gas flow (sweep gas off trial) were closely monitored for at least 2 h and decannulation was considered for patients who were stable during this period. The decision about total duration of weaning trial and decannulation were made by treating intensivists and an ECMO team.

Data collection and clinical outcomes

We retrospectively reviewed and obtained clinical and laboratory data from our institution`s ECMO database, which prospectively registered all patients who were treated with ECMO since 2012. Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, and lung injury score were estimated by the worst value within the first 24 h in the intensive care unit (ICU) admission. For prediction of survival after ECMO support, the respiratory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survival prediction (RESP) score10 and predicting death for severe ARDS on VV ECMO (PRESERVE) score15 were calculated on the first day of ECMO support. Driving pressure was calculated as peak inspiratory pressure minus positive end-expiratory pressure because all patients underwent ventilation with pressure-control mode in which the peak pressure can be used as a surrogate for plateau pressure.16

An etiological diagnosis was considered when a respiratory pathogen was isolated from a usually sterile specimen, pneumococcal antigen was detected in urine, or a predominant microorganism was isolated from adequate sputum or bronchial washing fluids with compatible Gram staining, as previously reported.17 Multidrug resistant (MDR) pathogens were identified by an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance,18 which is nonsusceptible to at least one agent in three antimicrobial categories. The appropriateness of antibiotic therapy was analyzed for all cases with etiological diagnoses according to susceptibility test criteria for lower respiratory tract pathogens. Antibiotic therapy was classified as inappropriate if the initially prescribed antibiotics were not active against the identified pathogens based on in vitro susceptibility testing.19 The antibiotic treatments for pneumonia were in line with the clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society,6,7 and the adequacy of antibiotics therapy, including the appropriateness of antibiotics selection, dosing, and duration were routinely assessed by infectious disease specialists in our hospital. We usually administered antibiotics active against the identified pathogens for 7–10 days, but sometimes longer duration of antibiotics might be indicated, depending upon the rate of improvement of clinical, radiologic, and laboratory parameters.

The primary outcome in this study was survival to discharge from hospital. Secondary outcomes were success of weaning from MV and ECMO, duration of ECMO support, appropriateness of antibiotic therapy, ECMO-related complications, and 30-day and 90-day mortality after ECMO initiation. We identified data related to clinical outcomes by review of hospital medical records.

Statistical analyses

The data are presented as median and interquartile range for continuous variables and as number (percent) for categorical variables. The data were analyzed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, and the Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. To estimate whether type of pneumonia was associated with survival to discharge, we performed multivariable logistic regression analysis to adjust for age, sex, type of pneumonia, and factors with p < 0.2 on univariate analysis. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

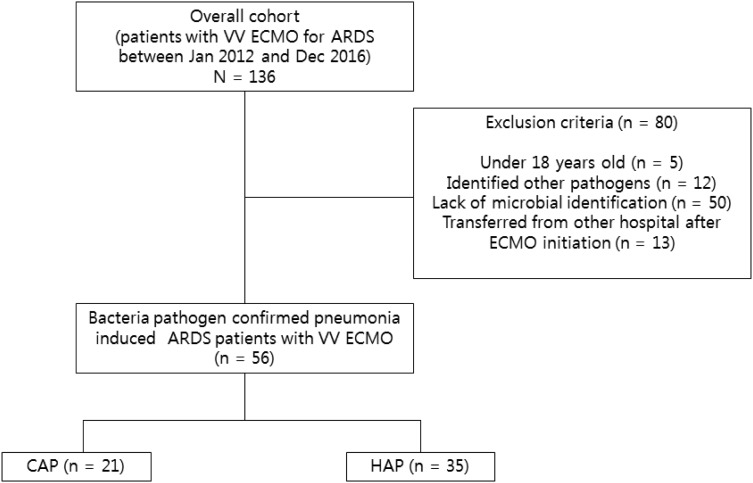

During the study period, a total of 136 patients were identified as having bacterial pneumonia-induced ARDS and receiving VV ECMO support. We excluded 50 patients lacked microbial identification, 13 patients transferred from other hospitals after ECMO initiation, 12 patients with nonbacterial pathogens, and 5 patients under 18 years of age (Figure 1). Thus, 56 bacterial pneumonia patients with ARDS receiving VV ECMO were included in this study. The baseline characteristics and clinical features of the two groups are presented in Table 1. There were 21 patients (37.5%) with CAP and 35 patients (62.5%) with HAP. The patients with HAP were older, more likely to be male, and had higher body mass index. However, these differences were not significant. Comorbidities, such as malignancy, chronic lung disease, diabetes, neurologic disease, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease, were not significantly different between the two groups. APACHE II (22.0 versus 22.5, p = 0.382) and SOFA scores (8 versus 8, p = 0.893) were not different between the two groups. In addition, vasoactive-inotropic (4 versus 3, p = 0.417) and lung injury scores (2.84 versus 2.67, p = 0.107) were not different between the two groups at the time of ICU admission.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; VV, venovenous.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with pneumonia receiving venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 56) | CAP (n = 21) | HAP (n = 35) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.50 (50.50–67.00) | 55 (49–71) | 62 (50–67) | 0.850 |

| Sex, male | 42 (75.0) | 15 (71.4) | 27 (77.1) | 0.752 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.45 (20.55–25.4) | 23.3 (19.3–25.35) | 23.5 (22.1–25.4) | 0.340 |

| Transferred from other hospital | 15 (26.8) | 6 (28.6) | 9 (25.7) | 0.336 |

| Co-morbidity | ||||

| Malignancy | 16 (28.6) | 6 (28.6) | 10 (28.6) | >0.999 |

| Chronic lung disease | 22 (39.3) | 5 (23.8) | 17 (48.6) | 0.092 |

| Diabetes | 14 (25.0) | 6 (10.7) | 8 (22.9) | 0.752 |

| Neurologic disease | 2 (3.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | >0.999 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 3 (5.4) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (5.7) | 0.740 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7 (12.5) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (17.1) | 0.237 |

| APACHE II score | 22.0 (16.6–28.8) | 22.0 (19.0–28.5) | 22.5 (15.0–29.5) | 0.382 |

| SOFA score | 8 (5–13) | 8 (5–15) | 8 (4–13) | 0.893 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 13 (23.2) | 5 (23.8) | 8 (22.9) | 0.790 |

| Vasoactive-inotropic score | 3 (1–4) | 4 (3–4) | 3 (0–4) | 0.417 |

| Lung injury score | 2.67 (2.44–3.50) | 2.84 (2.00–3.33) | 2.67 (2.33–3.50) | 0.107 |

Values are given as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BMI, body mass index; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Medical management prior to ECMO

Treatment modalities for patients in severe respiratory failure with pneumonia prior to ECMO initiation are presented in Table 2. The duration of MV prior to initiation of ECMO was similar in the CAP and HAP groups. Measurements performed during MV prior to ECMO, including positive end-expiratory pressure, peak inspiratory pressure, driving pressure, tidal volume per predicted body weight, and worst values of arterial blood gases, were not different between the two groups. Adjunctive or rescue therapies for severe respiratory failure including steroids, neuromuscular blocking agents, prone positioning, and inhaled nitric oxide were similar between the two groups. Finally, RESP and PRESERVE scores were similar between the two groups.

Table 2.

Medical management prior to venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

| Medical management | Total (N = 56) | CAP (n = 21) | HAP (n = 35) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of MV before ECMO, days | 7.58 (5.35–12.14) | 7.11 (5.25–9.33) | 7.85 (5.92–13.22) | 0.542 |

| < 2 days | 22 (39.3) | 9 (42.9) | 13 (37.1) | 0.780 |

| 2–7 days | 18 (32.1) | 6 (28.3) | 12 (34.3) | 0.551 |

| > 7 days | 16 (28.6) | 6 (28.6) | 10 (28.6) | >0.999 |

| Pre-ECMO treatment | ||||

| NMBA | 30 (53.6) | 11 (52.4) | 19 (54.3) | 0.511 |

| Nitric oxide | 10 (17.9) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (7.1) | 0.152 |

| Prone position | 6 (10.7) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (8.6) | 0.661 |

| Steroid | 7 (12.5) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (7.1) | 0.734 |

| Pre-ECMO MV setting | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2 | 74.4 (54.6–92.0) | 71.05 (53.15–88.99) | 76.45 (55.53–96.87) | 0.287 |

| PEEP, cmH2O | 10.00 (5.00–12.00) | 10.00 (5.75–12.25) | 9.00 (5.00–11.50) | 0.246 |

| Minute volume, l/min | 9.00 (7.40–10.73) | 10.45 (7.30–13.03) | 8.80 (7.48–9.28) | 0.114 |

| Tidal volume/PBW, ml/kg | 7.2 (5.2–9.2) | 7.2 (5.4–9.0) | 7.1 (5.0–9.3) | 0.125 |

| Peak inspiratory pressure, cmH2O | 30.00 (24.75–32.00) | 30.00 (24.75–33.25) | 28.50 (22.75– 30.00) | 0.454 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 24.00 (20.00–27.75) | 25.00 (21.50–32.00) | 22.00 (20.00– 25.75) | 0.080 |

| Driving pressure, cmH2O | 16.00 (14.00–20.00) | 16.00 (14.00–20.00) | 15.00 (14.00–20.00) | 0.544 |

| Pre-ECMO blood gas | ||||

| pH | 7.259 (7.127–7.362) | 7.259 (7.127–7.362) | 7.264 (7.127– 7.422) | 0.334 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 59.9 (49.8–73.5) | 59.9 (49.8–73.5) | 58.6 (47.9–73.5) | 0.768 |

| PaO2, mmHg | 59.1 (53.4–70.0) | 59.1 (53.4–70.0) | 58.7 (52.8–70.0) | 0.008 |

| HCO3−, mmol/l | 26.0 (22.7–30.5) | 26.0 (22.7–30.5) | 26.5 (23.0–30.5) | 0.084 |

| SaO2, % | 86.8 (82.6–91.3) | 86.9 (82.6–91.3) | 86.7 (82.1–91.3) | >0.999 |

| RESP score | 0.00 (−1.00–2.00) | 0.00 (−1.50–2.00) | 1.00 (−1.00–3.00) | 0.179 |

| PRESERVE score | 4.50 (3.00–6.75) | 4.00 (2.50–6.00) | 5.00 (4.00–7.00) | 0.107 |

Values are given as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; MV, mechanical ventilation; NMBA, neuromuscular blocking agents; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood; PBW, predictive body weight; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PRESERVE, predicting death for severe ARDS on venovenous ECMO; RESP, respiratory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survival prediction; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

Laboratory and microbiologic characteristics

As shown in Table 3, laboratory findings were not different between the two groups. The distributions of pathogens are shown in Table 3. The most common pathogens were Streptococcus pneumonia in the CAP group (n = 12, 57.1%) and Acinectobacter baumanii in the HAP group (n = 13, 37.1%). The presence of MDR pathogens was more common in patients with HAP than in those with CAP; however, these findings were not significantly different between the two groups (57.1% versus 74.3%, p = 0.125). In addition, the appropriateness of initial antibiotic therapy was not different (66.7% versus 60.0%, p = 0.843).

Table 3.

Laboratory and microbiologic characteristics in the patients with pneumonia receiving venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 56) | CAP (n = 21) | HAP (n = 35) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| Lactic acid, mmol/l | ||||

| Pre-ECMO | 3.07 (1.67–4.49) | 3.91 (1.78–6.74) | 2.83 (1.42–3.26) | 0.119 |

| Post-ECMO 6 h | 3.18 (1.95–5.86) | 3.32 (2.42–11.37) | 2.84 (1.70–4.59) | 0.174 |

| Post-ECMO 24 h | 2.13 (1.56–2.95) | 2.23 (1.71–6.24) | 1.99 (1.26–2.68) | 0.111 |

| Post-ECMO 48 h | 1.93 (1.38– 2.78) | 2.14 (1.73–4.59) | 1.69 (1.17–2.67) | 0.068 |

| WBC, 103/ml | 14.49 (8.73–20.13) | 13.22 (7.16–19.22) | 15.45 (10.88–20.04) | 0.273 |

| Platelet, 103/ml | 151.04 (52.00–210.25) | 134.61 (41.75–183.75) | 192.28 (90.75– 204.75) | 0.089 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 1.60 (0.50–1.75) | 1.50 (0.50–1.82) | 1.73 (0.40–1.80) | 0.865 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.59 (0.68–1.86) | 1.71 (0.75–1.94) | 1.22 (0.61–1.64) | 0.391 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 5.55 (2.69–13.74) | 4.17 (1.32–10.25) | 6.73 (2.25–15.64) | 0.643 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/ml | 2.35 (0.45–7.35) | 2.05 (0.15–6.25) | 2.55 (0.50–8.94) | 0.873 |

| Microbiologic parameters | ||||

| Culture positive specimen | ||||

| Trans-tracheal aspirate | 44 (78.6) | 17 (81.0) | 27 (77.1) | 0.932 |

| Blood | 16 (28.6) | 9 (42.9) | 7 (20.0) | 0.104 |

| Broncho-alveolar lavage fluid | 8 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | 5 (14.3) | >0.999 |

| Pleural fluid | 5 (8.9) | 2 (9.5) | 3 (8.8) | 0.765 |

| Microbiologic results | ||||

| Gram-positive pathogens | ||||

| CN Staphylococcus | 3 (5.4) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 (1.8) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Kocuria kristinae | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.7) | |

| MRSA | 7 (12.5) | 2 (9.5) | 5 (14.3) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Streptococcus mitis | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Streptococcus pneumonia | 17 (30.4) | 12 (57.1) | 5 (14.3) | |

| Gram-negative pathogens | ||||

| Acinetobacter baumanii | 18 (32.1) | 5 (23.8) | 13 (37.1) | |

| Escherichia coli | 2 (3.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 2 (3.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 3 (5.4) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Mycoplasma pneumonia | 1 (1.8) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Prevotella bivia | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 6 (10.7) | 4 (19.0) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 (1.8) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 3 (5.4) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Occurrence of MDR pathogen | 38 (67.9) | 12 (57.1) | 26 (74.3) | 0.125 |

| Inappropriate initial antibiotic treatment | 21 (37.5) | 7 (33.3) | 14 (40.0) | 0.843 |

Values are given as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; CN, coagulase negative; CRP, C-reactive protein; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; MDR, multidrug resistance; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; WBC, white blood cell.

Medical management after ECMO initiation

Treatment modalities during the first 72 h after ECMO initiation are presented in Table 4. The post-ECMO MV setting was similar in the CAP and HAP groups. In addition, the need for organ supports such as vasopressors and renal replacement therapy were not different. Finally, SOFA scores during the first 72 h after ECMO initiation were not different between the two groups.

Table 4.

Managements during the first 72 hours after initiation of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

| Medical management | Total (N = 56) | CAP (n = 21) | HAP (n = 35) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-ECMO MV setting | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2 | 81 (61–99) | 79 (59–99) | 81 (62–99) | 0.455 |

| PEEP, cmH2O | 9 (6–12) | 9 (6–12) | 9 (5–12) | 0.358 |

| Tidal volume/ PBW, ml/kg | 7.2 (5.2–9.2) | 7.2 (5.4–9.0) | 7.1 (5.0–9.3) | 0.125 |

| Peak inspiratory pressure, cmH2O | 25 (17–28) | 25 (17–28) | 25 (18–29) | 0.367 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 22 (18–26) | 22 (19–26) | 21 (18–25) | 0.175 |

| Driving pressure, cmH2O | 15 (13–17) | 16 (13–17) | 15 (13–17) | 0.322 |

| Acute kidney injury Renal replacement therapy |

5 (8.9) 2 (3.6) |

2 (9.5) 1 (4.8) |

3 (8.6) 1 (2.9) |

0.765 0.190 |

| Vasopressors | 6 (10.7) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (8.6) | 0.661 |

| SOFA score | 10 (5–17) | 11 (4–17) | 10 (5–18) | 0.623 |

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood; PBW, predictive body weight; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes of patients with bacterial pneumonia-induced ARDS who received VV ECMO support are given in Table 5. Of 56 patients, 2 patients (3.6%) required conversion to venoarterial ECMO because of hemodynamic instability due to right ventricular failure and 36 patients (64.3%) died during the hospitalization. Multi-organ failure related with severe pneumonia was the leading cause of death in both CAP and HAP groups (57.1% versus 54.5%, p = 0.780). In addition, death due to an ECMO-related complication occurred in eight patients (21.4% versus 22.7%, p = 0.342). However, survival to hospital discharge, the primary endpoint in this study, was not different between the two groups (38.1% versus 37.1%, p > 0.999). In addition, other clinical outcomes including weaning from MV and ECMO, ECMO-related complications, 30-day mortality, and 90-day mortality were similar in the CAP and HAP groups. Duration of MV and ECMO and lengths of ICU and hospital stays were not different between the two groups. Univariable analysis and multivariable logistic regression analysis were used to identify variables for survival to discharge that had significant prognostic value in Table 6. There were no significantly and independently variables associated with survival to discharge.

Table 5.

Clinical outcomes of the patients with pneumonia receiving venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

| Clinical outcomes | Total (N = 56) | CAP (n = 21) | HAP (n = 35) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival to hospital discharge | 20 (35.7) | 7 (33.3) | 13 (37.1) | >0.999 |

| MV duration after ECMO initiation, days | 3.0 (1.0–4.5) | 3.5 (1.0–5.0) | 3.0 (1.0–4.5) | 0.454 |

| Conversion to VA ECMO | 2 (3.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | 0.190 |

| MV weaning success | 23 (41.1) | 7 (33.3) | 16 (45.7) | 0.152 |

| ECMO weaning success | 26 (46.4) | 10 (47.6) | 16 (45.7) | >0.999 |

| ECMO duration, days | 13.75 (5.55–29.40) | 14.00 (4.50–39.50) | 13.00 (6.00–25.00) | 0.582 |

| ECMO-related complication | 15 (26.8) | 6 (28.6) | 9 (25.7) | 0.355 |

| Oxygenator failure | 5 (8.9) | 2 (9.5) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Cannula site bleeding | 3 (5.4) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Limb ischemia | 2 (3.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Hemolysis | 3 (5.4) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Stroke | 2 (3.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | |

| ICU LOS, days | 26.00 (15.75–35.50) | 26.00 (15.75–35.50) | 26.00 (14.75–35.50) | 0.733 |

| Hospital LOS, days | 39.50 (19.75–56.00) | 39.50 (19.75–56.00) | 40.50 (19.50–56.00) | 0.828 |

| 30-day mortality | 22 (39.3) | 9 (42.9) | 13 (23.2) | 0.780 |

| 90-day mortality | 35 (62.5) | 14 (66.7) | 21 (60) | >0.999 |

Values are given as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; LOS, length of stay; MV, mechanical ventilation; VA, venoarterial.

Table 6.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis for clinical variables associated with survival to discharge in study patients.

| Variable | Univariable |

Multivariable |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.1608 | 0.97 | 0.93–1.01 | 0.5797 | 0.12 | 0.00–222.87 |

| SOFA score | 0.1420 | 0.90 | 0.78–1.04 | 0.6577 | 1.08 | 0.78–1.48 |

| Pre-ECMO nitric oxide | 0.1903 | 0.33 | 0.06–1.73 | 0.4389 | 0.36 | 0.03–4.81 |

| Pre-ECMO respiratory rate | 0.1037 | 1.11 | 0.98–1.26 | 0.0523 | 1.31 | 1.00–1.72 |

| RESP score | 0.0604 | 1.25 | 0.99–1.59 | 0.9278 | 0.98 | 0.63–1.51 |

| PRESERVE score | 0.0608 | 0.77 | 0.58–1.01 | 0.5237 | 0.84 | 0.50–1.42 |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI, confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; OR, odds ratio; PRESERVE, predicting death for severe ARDS on venovenous ECMO; RESP, respiratory ECMO survival prediction; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether clinical outcomes differed between CAP and HAP in ARDS patients treated with ECMO. Our results demonstrate that patients with bacterial pneumonia requiring ECMO for respiratory support have high mortality regardless of pneumonia category. Furthermore, lengths of ICU and hospital stays, as well as weaning rates from MV and ECMO, were not different between patients with CAP and HAP.

Patients with advanced age, malnutrition, immunosuppression, and severe acute or chronic illness have increased risks of developing HAP.20,21 These factors are also associated with increased mortality, regardless of the category of pneumonia.22 Therefore, patients with HAP are expected to have worse prognoses than patients with CAP. This view is supported by the findings of a previous study, in which the incidence of complications and the need for intensive care were higher in patients with HAP compared with patients with CAP.8 Venditti and colleagues also reported that patients with HAP had higher pneumonia severity index and SOFA scores, longer hospital stays, and higher hospital mortality than patients with CAP.9 However, they excluded ICU patients from their analysis; therefore, their cohort was characterized by significantly less severe disease than the patients included in our study.

In other studies including patients admitted to ICUs, severity of illness did not differ between CAP and HAP.22–24 Furthermore, there were no differences in mortality rates according to the category of pneumonia, consistent with our results. Although the risk of organ failure including ARDS is high in patients with HAP, the category of pneumonia does not affect prognosis in critically ill patients with bacterial pneumonia, in whom organ failure requiring mechanical support has already developed. Therefore, type of pneumonia should not be considered when making treatment decisions for patients with ARDS caused by bacterial pneumonia who are to be placed on ECMO.

In critically ill patients with pneumonia, inappropriate antibiotic treatment is related to higher mortality.25–27 Patients with HAP are more likely to be exposed to antibiotic-resistant bacteria than patients with CAP and therefore are at risk of inappropriate initial empiric antibiotic treatment based on microbiological characteristics.6 In the present study, however, the rates of MDR pathogen occurrence were similar between CAP and HAP groups. In addition, the appropriateness of initial antibiotic therapy did not differ. These findings could help explain why we observed no differences in clinical outcomes between the two groups.

Although this study provides new information regarding outcome prediction in pneumonia patients with ARDS receiving ECMO support, it also has some limitations that should be considered. First, because it was conducted as a retrospective cohort study, there is always the possibility that selection bias influenced the significance of our findings. However, the data were prospectively collected from all patients who consecutively received ECMO support for ARDS caused by bacterial pneumonia at our institution. Nonetheless, limited number of patients enrolled might not be sufficiently powered to detect a significant difference between the groups. Second, our study was based at a single institution with a multidisciplinary ECMO team,14 which could limit the generalizability of our findings to other hospitals. Finally, patients with culture-negative results were excluded from the study. Thus, the true incidence of MDR pathogens and their effects on outcomes may be underestimated.

In summary, patients with severe acute respiratory failure requiring ECMO for respiratory support suffered severe disease regardless of whether they were diagnosed with CAP or HAP, and there were no significant differences in weaning rates from ECMO and survival according to the category of pneumonia.

Acknowledgments

C. Park and S. J. Na contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a Samsung Medical Center grant (OTA1602901).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Kyeongman Jeon  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4822-1772

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4822-1772

Contributor Information

Chul Park, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Soo Jin Na, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Chi Ryang Chung, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Yang Hyun Cho, Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Gee Young Suh, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea; Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Kyeongman Jeon, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea; Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1. Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012; 307: 2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson BT, Chambers RC, Liu KD. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 374: 1351–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pham T, Combes A, Roze H, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for pandemic influenza A(H1N1)-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome: a cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187: 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thiagarajan RR, Barbaro RP, Rycus PT, et al. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry International Report 2016. ASAIO J 2017; 63: 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63: e61–e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(Suppl. 2): S27–S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chow C, Lee-Pack L, Senathiragah N, et al. Community acquired, nursing home acquired and hospital acquired pneumonia: a five-year review of the clinical, bacteriological and radiological characteristics. Can J Infect Dis 1995; 6: 317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Venditti M, Falcone M, Corrao S, et al. Outcomes of patients hospitalized with community-acquired, health care-associated, and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schmidt M, Bailey M, Sheldrake J, et al. Predicting survival after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory failure. The Respiratory Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Survival Prediction (RESP) score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 1374–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171: 388–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1301–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, et al. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Na SJ, Chung CR, Choi HJ, et al. The effect of multidisciplinary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation team on clinical outcomes in patients with severe acute respiratory failure. Ann Intensive Care 2018; 8: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmidt M, Zogheib E, Roze H, et al. The PRESERVE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1704–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmidt MFS, Amaral A, Fan E, et al. Driving Pressure and Hospital Mortality in Patients Without ARDS: A Cohort Study. Chest 2018; 153: 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park HK, Song JU, Um SW, et al. Clinical characteristics of health care-associated pneumonia in a Korean teaching hospital. Respir Med 2010; 104: 1729–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18: 268–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Micek ST, Kollef KE, Reichley RM, et al. Health care-associated pneumonia and community-acquired pneumonia: a single-center experience. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51: 3568–3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sopena N, Heras E, Casas I, et al. Risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia outside the intensive care unit: a case-control study. Am J Infect Control 2014; 42: 38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nair GB, Niederman MS. Nosocomial pneumonia: lessons learned. Crit Care Clin 2013; 29: 521–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boots RJ, Lipman J, Bellomo R, et al. Disease risk and mortality prediction in intensive care patients with pneumonia. Australian and New Zealand practice in intensive care (ANZPIC II). Anaesth Intensive Care 2005; 33: 101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karhu J, Ala-Kokko TI, Ylipalosaari P, et al. Hospital and long-term outcomes of ICU-treated severe community- and hospital-acquired, and ventilator-associated pneumonia patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011; 55: 1254–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Vught LA, Scicluna BP, Wiewel MA, et al. Comparative Analysis of the Host Response to Community-acquired and Hospital-acquired Pneumonia in Critically Ill Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 1366–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ibrahim EH, Sherman G, Ward S, et al. The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting. Chest 2000; 118: 146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garnacho-Montero J, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Barrero-Almodovar A, et al. Impact of adequate empirical antibiotic therapy on the outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit with sepsis. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: 2742–2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muscedere JG, Shorr AF, Jiang X, et al. The adequacy of timely empiric antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia: an important determinant of outcome. J Crit Care 2012; 27: 322.e7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]