Abstract

Background

Use of routine medical care (RMC) is advocated to address ethnic/racial disparities in chronic kidney disease (CKD) risks, but use is less frequent among African Americans. Factors associated with low RMC use among African Americans at risk of renal outcomes have not been well studied.

Methods

We examined sociodemographic, comorbidity, healthcare access, and psychosocial (discrimination, anger, stress, trust) factors associated with low RMC use in a cross-sectional study. Low RMC use was defined as lack of a physical exam within one year among participants with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio > 30 mg/g) or CKD risk factors (diabetes or hypertension). We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate the odds of low RMC use at baseline (2000–2004) for several risk factors.

Results

Among 3191 participants with CKD, diabetes, or hypertension, 2024 (63.4%) were ≥ 55 years of age, and 700 (21.9%) reported low RMC use. After multivariable adjustment, age < 55 years (OR 1.61 95% CI 1.31–1.98), male sex (OR 1.71; 1.41–2.07), <high school diploma (OR 1.31; 1.07–1.62), absence of hypertension (OR 1.74; 1.27–2.39) or diabetes (OR 1.34; 1.09–1.65), and tobacco use (OR 1.43; 1.18–1.72) were associated with low RMC use. Low trust in providers (OR 2.16; 1.42–3.27), high stress (OR 1.41; 1.09–1.82), high daily discrimination (OR 1.30; 1.01–1.67) and low burden of lifetime discrimination (OR 1.52; 1.18–1.94), were also associated with low RMC use.

Conclusions

High-risk African Americans who were younger, male, less-educated, and with low trust in providers were more likely to report low RMC use. Efforts to improve RMC use by targeting these populations could mitigate African Americans’ disparities in CKD risks.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12882-018-1190-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Trust, Routine care

Background

African Americans, especially those with diabetes, hypertension, or a family history of chronic kidney disease (CKD), have two- to four-fold greater incidence of end stage renal disease (ESRD) or death when compared to their non-minority counterparts with similar CKD risk factors [1–3]. Poor access to health care, more commonly reported among ethnic/racial minorities than non-minorities, is thought to partially contribute to African Americans’ excess CKD-related health risks [4, 5]. Receipt of routine medical care (RMC) facilitates receipt of important preventive care services and health education, [6] with lack of RMC contributing to ethnic/racial disparities in these services [7, 8].

While greater use of RMC is widely advocated as a potential solution to address disparities in CKD, African Americans at risk of CKD have been shown to use RMC less frequently than non-African Americans [5]. However, reasons for low use of RMC among African Americans with CKD risk factors are not well-understood. In studies of diverse populations, individuals with CKD risk factors such diabetes or hypertension have been known to have low perceived susceptibility to CKD [9–11], and those with established kidney dysfunction have low rates of CKD awareness [12, 13]. These factors may contribute to limited engagement with the health care process. Little is known about how other sociodemographic factors, comorbidity, healthcare access (e.g. health insurance and type of coverage), or psychosocial factors (e.g. anger or stress) contribute to suboptimal RMC use among African Americans at risk of CKD. Improved understanding of additional factors associated with low use of RMC could inform efforts to eliminate disparities in CKD outcomes among African Americans.

We assessed low use of RMC among African Americans enrolled in the Jackson Heart Study (JHS) who were at risk of CKD incidence or progression. The JHS collects a unique battery of psychosocial questionnaires including assessments of stress, discrimination, anger and trust. Using this rich data we assess participants’ demographic, medical, socioeconomic and psychosocial characteristics associated with use of RMC thereby providing a more comprehensive evaluation of factors affecting RMC in African Americans with or at risk for CKD than currently available in the literature. Given the high burden of CKD in this group, understanding barriers to care will be critical to implementation of preventive interventions.

Methods

Study population

The JHS is a prospective cohort study of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in African American residents living in the tri-county area (Hinds, Madison, and Rankin) of the metropolitan statistical area of Jackson, Mississippi. Detailed study procedures and recruitment are described elsewhere [14, 15]. Briefly, African Americans living in Jackson, Mississippi – including participants from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) and their family members, were recruited and examined during the JHS baseline visit (2000–2004), comprising a final baseline cohort of 5306 African Americans 21–94 years of age. Participants completed questionnaires which captured information on socio-demographics, comorbidity, healthcare utilization, and psychosocial factors including trust in their medical care and, moods such as anger, perceived stress, and perceived discrimination. Participants also underwent standard physical examinations (including blood pressure [BP] measurement) and laboratory studies (including measures of kidney function and glycemic control). Each participant provided written informed consent, and the institutional review boards at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson State University, and Tougaloo College approved the JHS study protocol.

Assessment of comorbidities

We identified individuals with CKD, hypertension or diabetes in the JHS cohort during the baseline visit. Using the JNC 7 criteria for detection of hypertension [16], we included individuals with measured BP > 140/90 mmHg or with self-reported use of BP lowering medication. We defined diabetes as fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1C ≥6.5%, or use of diabetes medications within 2 weeks prior to the clinic visit [17]. We defined CKD as the presence of an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 using the CKD-EPI formula [18] or a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) > 30 mg/g on spot collection or 24 h urine collection if a spot urine collection was unavailable. We included only individuals with complete demographic, comorbidity, and psychosocial data in the analysis.

Assessment of psychosocial factors

We included several baseline psychosocial factors in the present analysis: trust in medical care, perceived discrimination, anger, and stress. Among participants who self-reported access to health care, we ascertained their trust in medical care using the question: “Thinking about the place you usually go for help with your medical problems, in general, how much do you trust them to take good care of you? Do you trust them very much, somewhat, not very much, or not at all?” We considered participants responding “very much” or “somewhat” to have high trust in medical care, and those responding “not very much” or “not at all” to have low trust in medical care.

The multidimensional Jackson Heart Study Discrimination Instrument (JHSDIS) – developed specifically for use in the JHS cohort – assessed perceived social discrimination [19]. The JHSDIS evaluated three dimensions of perceived discrimination: daily discrimination, lifetime discrimination, and burden of lifetime discrimination. Daily discrimination consisted of responses to 9 statements each prefaced with the question: “How often on a day-to-day basis do you have the following experiences?” Statements captured treatment with less courtesy, or less respect; receipt of poor service at a restaurant; and several examples of profiling with regard to factors such as intelligence, hostility/violence, honesty, and others. Participants rated the frequency of these experiences on a scale from 0 (no experiences) to 6 (several times a day) and responses were compiled into a summary score.

To assess lifetime discrimination, participants were asked to answer yes or no to questions about unfair treatments over their lifetime across 9 domains capturing aspects of daily living such as school, job search, workplace, buying a house, accessing resources/services, including medical care, and use of public spaces. The count of the domains (range 0–9) was the lifetime social discrimination score. The burden of lifetime social discrimination was based on a summed score of the points in response to 3 questions: “when you have had experiences like these over your lifetime, would you say they have been very stressful [3 points], moderately stressful [1.5 points], or not stressful [0 points]?”, “overall, how much has discrimination interfered with you having a full and productive life? Would you say a lot [3 points], some, a little, or not at all [0 points]?”, and “overall, how much harder has your life been because of discrimination? Would you say a lot [3 points], some [2 points], a little [1 points], or not at all [0 points]?” We categorized overall scores for daily, lifetime, and burden of lifetime discrimination into tertiles.

Anger was measured using the Spielberger trait anger scale, a 16-item scale that assesses anger-in (8 items) and anger-out (8 items) [20]. Using a Likert scale (“almost never”, “sometimes”, “often”, and “almost always”), participants rated their anger reactions such as “I do things like slam doors,” or “I am secretly quite critical of others.” We summed responses within each subscale, and averaged the two summed scores as the overall anger score, which was then categorized into tertiles.

Participants’ responses to the Global Perceived Stress Scale – an 8-item measure of perceived chronic stress created for use in the JHS – assessed psychosocial stress [21]. Participants rated the severity of stress experienced over the 12 months prior to the baseline exam in 8 areas from 0 [not stressful] to 3 [very stressful]: employment, relationships, neighborhood, caring for others, legal problems, medical problems, racism and discrimination, and meeting basic needs [22]. We summed responses and categorized the composite score into tertiles.

Assessment of healthcare access and utilization

Participants self-reported their health insurance status and type of coverage. Participants also indicated difficulty obtaining healthcare services in response to the question “overall, how hard has it been for you to get health services you have needed? Would you say it has been very hard, fairly hard, not too hard, or not hard at all?” We considered those who responded “very hard” or “fairly hard” as having difficulty obtaining services. Participants rated their satisfaction with care based on their response to the question “overall, how satisfied are you with your regular (or most recent) doctor or health professional? Would you say you are very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, very dissatisfied, or not sure?” We considered those who responded with “very satisfied” or “somewhat satisfied” to be satisfied with their care.

Outcome assessment: Low use of routine medical care

We defined participants’ low use of RMC based on their responses to the question: “when was the last time you went to a doctor or other health professional for a routine physical exam or general check-up; that is when you were not sick or pregnant?” Possible responses were “within the past year”, “at least 1 year but less than 2 years ago”, “at least 2 years but less than 4 years ago”, “5 or more years ago”, or “never.” We considered participants who reported no receipt of a routine physical exam “within the past year” to have low use of RMC.

Statistics

In descriptive analyses, we summarized characteristics of study participants and compared these characteristics between those who reported low use vs. use of RMC using Chi-square tests. Because these analyses were descriptive, no adjustment for multiple testing was made. Using a multivariable logistic regression model, we estimated the odds of low RMC use by sociodemographic, comorbidity, healthcare access, and psychosocial factors. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, education, income, insurance, diabetes, hypertension, CVD history, smoking status, BMI, and CKD status. In a post hoc analysis exploring the impact of age on low use of RMC, we stratified the regression model by age (dichotomized at the cohort median: < 55 vs ≥55 years). All tests were two-sided at significance level α < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R 3.3.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study participants, sociodemographics, and comorbidity

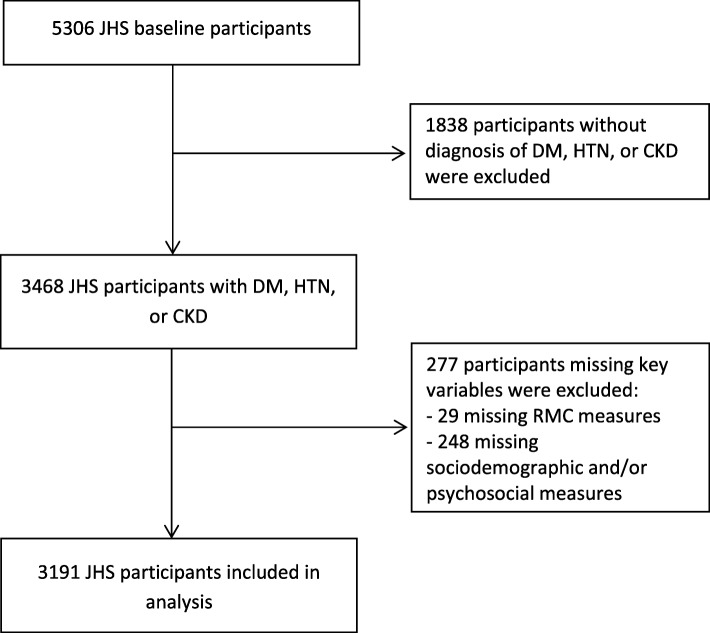

Of 5306 total JHS participants enrolled at baseline, 3468 (65.4%) had CKD, diabetes, or hypertension. Of these, we included 3191 participants who had complete data available for assessment of RMC use, access to care, and psychosocial factors (Fig. 1). Compared with available data on excluded participants, participants who met inclusion criteria were older, with less education, lower income, and more prevalent CVD, and were more likely to be insured. Included participants reported lower stress, daily discrimination, and burden of lifetime discrimination than those excluded from the analysis (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Derivation of analytic cohort

Among those included in the analysis, 700 (21.9%) reported low use of RMC. Participants reporting low use of RMC were more likely to be younger (age < 55 years: 48.6% vs. 33.2%), male (47.6% vs. 32.5%), or former/current smokers (42.6% vs. 32.8%) than those reporting use of RMC. Compared to those with RMC use, participants with low RMC use were less likely overall to have hypertension (88.3% vs. 92.9%) or diabetes (29.1% vs. 34.7%), but more likely to have uncontrolled hypertension (60.7% vs. 47.2%). Of 591 (18.5%) participants with CKD, those with low use of RMC were slightly less likely to have later stages of CKD than those with use of RMC (CKD stage 4 or 5: 3.9% vs. 7.6%). Few participants with CKD reported CKD awareness (13.7%), and there was no difference in CKD awareness between participants with or without use of RMC (14.3% vs. 11.7%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants, stratified by use of routine medical care

| Characteristic | All participants N = 3191 |

Age < 55 years N = 1167 (36.6%) |

Age ≥ 55 years N = 2024 (63.4%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | RMC use N = 2491 (78.1%) |

Low RMC use N = 700 (21.9%) |

P Value | RMC use N = 827 (33.2%) |

Low RMC use N = 340 (48.6%) |

P Value | RMC use N = 1664 (66.8%) |

Low RMC use N = 360 (51.4%) |

P Value | |

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 58.9 (11.39) | 59.85 (11.19) | 55.55 (11.47) | < 0.01 | 47 (5.93) | 45.67 (6.31) | < 0.01 | 66.23 (6.86) | 64.89 (6.21) | < 0.01 |

| Sex | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| Female | 2049 (64.21) | 1682 (67.52) | 367 (52.43) | 542 (65.54) | 158 (46.47) | 1140 (68.51) | 209 (58.06) | |||

| Male | 1142 (35.79) | 809 (32.48) | 333 (47.57) | 285 (34.46) | 182 (53.53) | 524 (31.49) | 151 (41.94) | |||

| Education | 0.09 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| ≤ High school diploma | 1389 (43.53) | 1064 (42.71) | 325 (46.43) | 184 (22.25) | 103 (30.29) | 880 (52.88) | 222 (61.67) | |||

| > High school diploma | 1802 (56.47) | 1427 (57.29) | 375 (53.57) | 643 (77.75) | 237 (69.71) | 784 (47.12) | 138 (38.33) | |||

| Income class categorya | 0.10 | 0.37 | 0.05 | |||||||

| Lower/Lower-middle | 1139 (35.69) | 876 (35.17) | 263 (37.57) | 218 (26.36) | 103 (30.29) | 658 (39.54) | 160 (44.44) | |||

| Upper-middle/Upper | 1548 (48.51) | 1204 (48.33) | 344 (49.14) | 472 (57.07) | 186 (54.71) | 732 (43.99) | 158 (43.89) | |||

| Missing | 504 (15.79) | 411 (16.5) | 93 (13.29) | 137 (16.57) | 51 (15) | 274 (16.47) | 42 (11.67) | |||

| Comorbidities & Behaviors | ||||||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.99 | |||||||

| < 30 | 1316 (41.24) | 1033 (41.47) | 283 (40.43) | 260 (31.44) | 115 (33.82) | 773 (46.45) | 168 (46.67) | |||

| ≥ 30 | 1875 (58.76) | 1458 (58.53) | 417 (59.57) | 567 (68.56) | 225 (66.18) | 891 (53.55) | 192 (53.33) | |||

| Tobacco use | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| Never | 2076 (65.06) | 1674 (67.2) | 402 (57.43) | 604 (73.04) | 209 (61.47) | 1070 (64.3) | 193 (53.61) | |||

| Former/current | 1115 (34.94) | 817 (32.8) | 298 (42.57) | 223 (26.96) | 131 (38.53) | 594 (35.7) | 167 (46.39) | |||

| Hypertension | < 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |||||||

| No | 259 (8.12) | 177 (7.11) | 82 (11.71) | 72 (8.71) | 47 (13.82) | 105 (6.31) | 35 (9.72) | |||

| Yes | 2932 (91.88) | 2314 (92.89) | 618 (88.29) | 755 (91.29) | 293 (86.18) | 1559 (93.69) | 325 (90.28) | |||

| Hypertension controlb | < 0.01 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Controlled | 1456 (49.66) | 1215 (52.51) | 241 (39) | 392 (51.92) | 103 (35.15) | 823 (52.79) | 138 (42.46) | |||

| Uncontrolled | 1467 (50.03) | 1092 (47.19) | 375 (60.68) | 363 (48.08) | 188 (64.16) | 729 (46.76) | 187 (57.54) | |||

| Diabetes | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.09 | |||||||

| No | 2122 (66.5) | 1626 (65.27) | 496 (70.86) | 600 (72.55) | 256 (75.29) | 1026 (61.66) | 240 (66.67) | |||

| Yes | 1069 (33.5) | 865 (34.73) | 204 (29.14) | 227 (27.45) | 84 (24.71) | 638 (38.34) | 120 (33.33) | |||

| Diabetes controlc | 0.66 | 0.4 | 0.8 | |||||||

| Controlled | 475 (44.43) | 381 (44.05) | 94 (46.08) | 83 (36.56) | 37 (44.05) | 298 (46.71) | 57 (47.5) | |||

| Uncontrolled | 556 (52.01) | 453 (52.37) | 103 (50.49) | 133 (58.59) | 46 (54.76) | 320 (50.16) | 57 (47.5) | |||

| CVD history | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.5 | |||||||

| No | 2741 (85.9) | 2128 (85.43) | 613 (87.57) | 764 (92.38) | 324 (95.29) | 1364 (81.97) | 289 (80.28) | |||

| Yes | 450 (14.1) | 363 (14.57) | 87 (12.43) | 63 (7.62) | 16 (4.71) | 300 (18.03) | 71 (19.72) | |||

| CKD | 0.73 | 0.33 | 0.13 | |||||||

| No | 1500 (47.01) | 1178 (47.29) | 322 (46) | 467 (56.47) | 183 (53.82) | 711 (42.73) | 139 (38.61) | |||

| Yes | 591 (18.52) | 463 (18.59) | 128 (18.29) | 113 (13.66) | 58 (17.06) | 350 (21.03) | 70 (19.44) | |||

| CKD stage d | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.46 | |||||||

| 1 or 2 | 297 (50.25) | 217 (46.87) | 80 (62.5) | 87 (76.99) | 50 (86.21) | 130 (37.14) | 30 (42.86) | |||

| 3 | 251 (42.47) | 209 (45.14) | 42 (32.81) | 18 (15.93) | 6 (10.34) | 191 (54.57) | 36 (51.43) | |||

| 4 or 5 | 40 (6.77) | 35 (7.56) | 5 (3.91) | 8 (7.08) | 2 (3.45) | 27 (7.71) | 3 (4.29) | |||

| CKD awareness d,e | 0.57 | 0.1 | 0.59 | |||||||

| No | 508 (85.96) | 396 (85.53) | 112 (87.5) | 95 (84.07) | 55 (94.83) | 301 (86) | 57 (81.43) | |||

| Yes | 81 (13.71) | 66 (14.25) | 15 (11.72) | 17 (15.04) | 3 (5.17) | 49 (14) | 12 (17.14) | |||

| Healthcare access & utilization | ||||||||||

| Health insurance | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| No | 385 (12.07) | 253 (10.16) | 132 (18.86) | 124 (14.99) | 84 (24.71) | 129 (7.75) | 48 (13.33) | |||

| Yes | 2806 (87.93) | 2238 (89.84) | 568 (81.14) | 703 (85.01) | 256 (75.29) | 1535 (92.25) | 312 (86.67) | |||

| Insurance type f | ||||||||||

| Medicare | 1128 (35.35) | 953 (38.26) | 175 (25) | < 0.01 | 64 (7.74) | 9 (2.65) | < 0.01 | 889 (53.43) | 166 (46.11) | 0.01 |

| Medicaid | 479 (15.01) | 393 (15.78) | 86 (12.29) | 0.03 | 62 (7.5) | 17 (5) | 0.16 | 331 (19.89) | 69 (19.17) | 0.81 |

| Private | 2052 (64.31) | 1616 (64.87) | 436 (62.29) | 0.22 | 622 (75.21) | 241 (70.88) | 0.14 | 994 (59.74) | 195 (54.17) | 0.06 |

| Usual source of care | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| No | 200 (6.27) | 93 (3.73) | 107 (15.29) | 41 (4.96) | 66 (19.41) | 52 (3.12) | 41 (11.39) | |||

| Yes | 2980 (93.39) | 2388 (95.87) | 592 (84.57) | 783 (94.68) | 274 (80.59) | 1605 (96.45) | 318 (88.33) | |||

| Obtaining care | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Less difficult | 2794 (87.56) | 2223 (89.24) | 571 (81.57) | 723 (87.42) | 263 (77.35) | 1500 (90.14) | 308 (85.56) | |||

| More difficult | 383 (12) | 262 (10.52) | 121 (17.29) | 102 (12.33) | 72 (21.18) | 160 (9.62) | 49 (13.61) | |||

| Satisfaction with care | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| Less satisfied | 154 (4.83) | 88 (3.53) | 66 (9.43) | 40 (4.84) | 38 (11.18) | 48 (2.88) | 28 (7.78) | |||

| More satisfied | 2992 (93.76) | 2393 (96.07) | 599 (85.57) | 784 (94.8) | 278 (81.76) | 1609 (96.69) | 321 (89.17) | |||

RMC routine medical care, BMI body mass index, CVD cardiovascular disease, CKD chronic kidney disease

aBased on family size, US Census poverty levels, and year of baseline clinic visit (2000–2004). Among participants with b hypertension, c diabetes, d,e CKD (< 100% due to n = 3 who could not be staged and n = 2 missing self-report data); fhealth insurance categories are not mutually exclusive

Healthcare access and utilization

Most participants had health insurance (n = 2806; 87.9%). Compared to participants with use of RMC, those with low RMC use were less likely to report having health insurance (81.1% vs. 89.8%) or a usual source of medical care (84.6% vs. 95.9%), but were more likely to report difficulty obtaining care (17.3% vs. 10.5%) and being less satisfied with care (9.4% vs. 3.5%; Table 1).

Distribution of psychosocial factors

Self-reported psychosocial factors are shown in Table 2. Overall, participants reporting low use of RMC were more likely to report low (vs. high) trust in their medical care compared to those with use of RMC (7.0% vs. 2.9%), although overall trust was high. Those with low use of RMC were more commonly in the highest tertile of stress score (44.3% vs. 36.9%) and daily discrimination score (41.3% vs. 33.5%) than participants reporting RMC use. Trust remained lower among individuals with low RMC use compared with RMC use in both the < 55 years old group and ≥ 55 year old groups. However, among participants aged ≥55 years, those with low use of RMC had lower scores on the burden of lifetime discrimination measure (lowest tertile: 37.5% vs. 30.5%) compared to those with use of RMC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of psychosocial factors among participants in Jackson Heart Study at baseline overall; stratified by use of routine medical care

| Psychosocial factors | All participants N = 3191 |

Age < 55 years N = 1167 (36.6%) |

Age ≥ 55 years N = 2024 (63.4%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | RMC use N = 2491 (78.1%) |

Low RMC use N = 700 (21.9%) |

P Value | RMC use N = 827 (33.2%) |

Low RMC use N = 340 (48.6%) |

P Value | RMC use N = 1664 (66.8%) |

Low RMC use N = 360 (51.4%) |

P Value | |

| Trust in carea | < 0.01 | 0 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Low | 111 (3.72) | 70 (2.93) | 41 (6.95) | 28 (3.56) | 25 (9.12) | 42 (2.62) | 16 (5.06) | |||

| High | 2870 (96.28) | 2321 (97.07) | 549 (93.05) | 758 (96.44) | 249 (90.88) | 1563 (97.38) | 300 (94.94) | |||

| Stress tertile | < 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.31 | |||||||

| Lowest | 859 (26.92) | 695 (27.9) | 164 (23.43) | 107 (12.94) | 45 (13.24) | 588 (35.34) | 119 (33.06) | |||

| Middle | 1102 (34.53) | 876 (35.17) | 226 (32.29) | 287 (34.7) | 105 (30.88) | 589 (35.4) | 121 (33.61) | |||

| Highest | 1230 (38.55) | 920 (36.93) | 310 (44.29) | 433 (52.36) | 190 (55.88) | 487 (29.27) | 120 (33.33) | |||

| Anger tertile | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.17 | |||||||

| Lowest | 626 (19.62) | 505 (20.27) | 121 (17.29) | 135 (16.32) | 46 (13.53) | 370 (22.24) | 75 (20.83) | |||

| Middle | 615 (19.27) | 485 (19.47) | 130 (18.57) | 181 (21.89) | 76 (22.35) | 304 (18.27) | 54 (15) | |||

| Highest | 768 (24.07) | 604 (24.25) | 164 (23.43) | 258 (31.2) | 94 (27.65) | 346 (20.79) | 70 (19.44) | |||

| Discrimination tertiles | ||||||||||

| Daily | < 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Lowest | 988 (30.96) | 793 (31.83) | 195 (27.86) | 166 (20.07) | 63 (18.53) | 627 (37.68) | 132 (36.67) | |||

| Middle | 1080 (33.85) | 864 (34.68) | 216 (30.86) | 285 (34.46) | 108 (31.76) | 579 (34.8) | 108 (30) | |||

| Highest | 1123 (35.19) | 834 (33.48) | 289 (41.29) | 376 (45.47) | 169 (49.71) | 458 (27.52) | 120 (33.33) | |||

| Lifetime | 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.13 | |||||||

| Lowest | 894 (28.02) | 704 (28.26) | 190 (27.14) | 164 (19.83) | 66 (19.41) | 540 (32.45) | 124 (34.44) | |||

| Middle | 1104 (34.6) | 845 (33.92) | 259 (37) | 273 (33.01) | 123 (36.18) | 572 (34.38) | 136 (37.78) | |||

| Highest | 1193 (37.39) | 942 (37.82) | 251 (35.86) | 390 (47.16) | 151 (44.41) | 552 (33.17) | 100 (27.78) | |||

| Burden of lifetime | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Lowest | 963 (30.18) | 731 (29.35) | 232 (33.14) | 223 (26.96) | 97 (28.53) | 508 (30.53) | 135 (37.5) | |||

| Middle | 1093 (34.25) | 853 (34.24) | 240 (34.29) | 301 (36.4) | 131 (38.53) | 552 (33.17) | 109 (30.28) | |||

| Highest | 1135 (35.57) | 907 (36.41) | 228 (32.57) | 303 (36.64) | 112 (32.94) | 604 (36.3) | 116 (32.22) | |||

RMC routine medical care

aAmong participants reporting a usual source of care and non-missing response to question regarding trust (n = 2981)

Factors independently associated with low use of routine medical care

In a multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for sociodemographics, comorbidities, and psychosocial factors, age < 55 years (OR 1.61; 95% CI 1.31–1.98), male sex (OR 1.71; 1.41–2.07), < high school diploma (OR 1.31; 1.07–1.62), and lack of health insurance (OR 1.52; 1.18–1.96) were associated with greater odds of low use of RMC overall (Table 3). Among participants ≥55 years, male sex and lack of health insurance were associated with greater odds of low RMC use (OR 1.56; 1.20–2.04, OR 1.69; 1.16–2.46, respectively), while male sex was significantly associated only in the < 55 years age group (OR 1.90; 1.43–2.54).

Table 3.

Factors associated with low use of routine medical care (RMC); stratified by age

| Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All participants | Age < 55 years | Age ≥ 55 years | |

| No. of events/N | 700/3191 | 340/1167 | 360/2024 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age | |||

| < 55 years | 1.61 (1.31, 1.98) | NA | NA |

| ≥ 55 years | Reference | NA | NA |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.71 (1.41, 2.07) | 1.90 (1.43, 2.54) | 1.56 (1.20, 2.04) |

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Education | |||

| < high school diploma | 1.31 (1.07, 1.62) | 1.37 (0.98, 1.91) | 1.30 (0.99, 1.70) |

| ≥ high school diploma | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Income category | |||

| Poor: lower-middle | 0.97 (0.78, 1.20) | 0.95 (0.68, 1.34) | 0.96 (0.72, 1.27) |

| Affluent: upper-middle | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Health insurance | |||

| No | 1.52 (1.18, 1.96) | 1.40 (0.98, 2.01) | 1.69 (1.16, 2.46) |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Comorbidities & Behaviors | |||

| Body mass index, Kg/m2 | |||

| < 30 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| ≥ 30 | 1.17 (0.97, 1.42) | 1.08 (0.80, 1.45) | 1.25 (0.97, 1.61) |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Former/current | 1.43 (1.18, 1.72) | 1.50 (1.12, 2.03) | 1.44 (1.12, 1.84) |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 1.74 (1.27, 2.39) | 1.71 (1.08, 2.71) | 1.79 (1.15, 2.79) |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 1.34 (1.09, 1.65) | 1.24 (0.88, 1.73) | 1.41 (1.08, 1.84) |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

| No | 1.12 (0.85, 1.47) | 1.89 (1.04, 3.42) | 0.93 (0.68, 1.27) |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

| No | 0.96 (0.75, 1.24) | 0.81 (0.54, 1.21) | 1.06 (0.76, 1.49) |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Psychosocial factors | |||

| Trust a | |||

| Low | 2.16 (1.42, 3.27) | 2.32 (1.29, 4.16) | 2.07 (1.13, 3.80) |

| High | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Stress tertile | |||

| Lowest | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Middle | 1.16 (.91, 1.48) | 1.03 (0.66, 1.62) | 1.18 (0.88, 1.58) |

| Highest | 1.41 (1.09, 1.82) | 1.29 (0.82, 2.01) | 1.41 (1.02, 1.94) |

| Anger tertile | |||

| Lowest | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Middle | 0.95 (0.71, 1.28) | 1.15 (0.73, 1.81) | 0.83 (0.55, 1.23) |

| Highest | 0.87 (0.65, 1.15) | 0.88 (0.56, 1.37) | 0.89 (0.61, 1.29) |

| Daily discrimination tertile | |||

| Lowest | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Middle | 1.05 (0.83, 1.34) | 1.10 (0.73, 1.66) | 1.03 (0.76, 1.40) |

| Highest | 1.30 (1.01, 1.67) | 1.15 (0.76, 1.75) | 1.46 (1.05, 2.03) |

| Lifetime discrimination tertile | |||

| Lowest | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Middle | 1.10 (0.86, 1.40) | 1.16 (0.76, 1.76) | 1.09 (0.81, 1.48) |

| Highest | 0.89 (0.68, 1.17) | 1.08 (0.70, 1.68) | 0.76 (0.53, 1.08) |

| Burden of discrimination tertile | |||

| Lowest | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Middle | 0.82 (0.65, 1.03) | 0.93 (0.65, 1.34) | 0.74 (0.54, 1.00) |

| Highest | 0.66 (0.51, 0.85) | 0.70 (0.47, 1.05) | 0.64 (0.46, 0.89) |

All models were adjusted for the covariates listed above

aAmong participants reporting a usual source of care and non-missing response to question regarding trust (n = 2981)

Among comorbidities and behaviors, tobacco use was associated with higher odds of low RMC use overall (OR 1.43; 1.18–1.72) and across age groups. Absence of comorbidities such as hypertension (OR 1.74; 1.27–2.39) or diabetes (OR 1.34; 1.09–1.65) was associated with greater odds of low use of RMC; the latter was driven by the ≥55 years age group. Participants < 55 years of age without CVD had greater odds of low RMC use than participants with CVD (OR 1.89; 1.04–3.42).

Participants reporting low trust had more than twice the odds of reporting low use of RMC compared to those with high trust (OR 2.16; 1.42–3.27) overall and across both age groups. Trust was the only psychosocial factor associated with low RMC use among participants < 55 years of age. Participants in the highest (vs. lowest) tertile of stress and daily discrimination also had higher odds of low use of RMC (OR 1.41; 1.02, 1.94, OR 1.46; 1.05–2.03, respectively), whereas participants in the highest (vs. lowest) tertile of burden of lifetime discrimination had lower odds of reporting low use of RMC (OR0.64; 0.46–0.89). After stratification by age, these findings were only evident among participants ≥55 years of age.

Discussion

In this large cohort of African Americans with CKD or at increased risk of CKD, younger age, male sex, low educational attainment, tobacco use, lack of health insurance, and low comorbidity were associated with low use of RMC. Psychosocial factors (e.g., low trust, high stress, high daily and low burden of lifetime discrimination) were also associated with low use of RMC among this high risk group. These results suggest that interventions focused on increasing trust and reducing stressors in non-health related activities could encourage more preventive care for African Americans and promote wellness.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously examine a number of factors associated with infrequent use of RMC among African Americans at high risk of poor CKD outcomes. The extent to which patients seek health care may directly affect their opportunities to have CKD detected and their CKD risk factors controlled, and their opportunities for education regarding the long-term health risks associated with CKD, particularly if that care is received episodically. While use of routine care creates opportunities for health education, preventive health services, disease management, and shared decision-making, these opportunities are less frequently encountered by African Americans than by whites [23, 24]. The reason for this difference is likely multifactorial. For instance, racial residential segregation may impact disparities in routine care, [25] as African Americans are more segregated from optimal healthcare facilities and information. This access to healthcare services directly relates to use of routine care [26–28]. In African American populations, this use of routine care has been linked to an identified usual source of care [7, 29], yet ethnic and racial minorities are routinely less likely to have an identified usual source of care than their white counterparts [30]. As a result, individuals without a usual source of care are more likely to utilize the emergency department for their healthcare needs than individuals with access to routine care [31], resulting in an expensive and inefficient method of obtaining health services.

Despite these findings, differences in healthcare access alone may not fully explain disparities in routine care use between African Americans and whites. Psychosocial factors and cultural norms may also influence use of routine care [29, 32, 33]. Our findings are consistent with prior literature suggesting low trust as a major barrier to health care engagement by African Americans [34]. Low trust in medical care among ethnic and racial minorities has been associated with lower medication adherence, reduced rates of preventive health services, worsened blood pressure control, and varying degrees of shared-decision making [35–40]. Factors contributing to low trust include patient perceptions of provider greed, discrimination, and the potential for medical experimentation based on the historical medical mistreatment of African Americans [41, 42]. Conversely, provider race concordance has been associated with higher levels of trust and patient engagement, [43–46] which may be due to a more positive physician affect and higher degree of person-centered communication noted more frequently in racially concordant office visits [47, 48]. It remains unclear how patterns of patient-provider interactions, for example, the degree of continuity of care by providers contribute to feelings of low trust among JHS participants. Further, we found incongruence between perceived discrimination and use of RMC, with high daily discrimination, yet low burden of lifetime discrimination to be associated with low RMC use. The latter finding contradicts our hypothesis that perceived discrimination would be associated with low use of RMC, but aligns with other JHS studies showing higher degrees of perceived burden of lifetime discrimination to be associated with more favorable outcomes (e.g. lower risk of left ventricular hypertrophy) [49]. This is hypothesized to be related to the aggregation of components in the burden of lifetime discrimination assessment, or potentially an age-related phenomenon. Evaluation of the individual questions in the burden assessment may produce different results.

Our findings suggest patterns of healthcare utilization differ between younger and older African Americans. Younger JHS participants were less engaged in RMC than older participants, aligning with prior studies showing young adults in the general population have less use of ambulatory medical care, [50, 51] and rate their health as a lower priority than adolescents or older adults [52]. Prior work has shown young adults with hypertension to be less frequently diagnosed by a provider than older adults with similar blood pressures, [53] receive lifestyle education more inconsistently, [54] and have high rates of hypertension unawareness [55]. Further, young adults with established CKD are at high risk of complications related to poor self-management skills and non-adherence, especially during transitions in care, [56] and are particularly vulnerable to poor CKD outcomes. While several studies have demonstrated improved survival on dialysis among older African Americans compared to whites, [57–60] young adult African Americans aged 18–30 have been shown to suffer a two-fold increase risk of death compared to age-matched whites and older African Americans [61, 62]. Tailored interventions promoting early engagement in RMC among young African Americans may mitigate CKD risks when the potential long-term impact on CKD outcomes is greatest.

Our study has limitations that should be noted. First, JHS participants reside in a single southeastern US metropolitan area with a high prevalence of CKD risk factors, which limits the generalizability of the study findings to African Americans in other areas of the US and to individuals residing outside of the US. Further, we did not have detailed information on specific characteristics that may influence RMC such as past personal or familiar medical experiences or provider race concordance, nor were we able to identify the directionality of our findings given the cross-sectional nature of our study. For example, we cannot determine if younger individuals were more likely to be diagnosed with CVD because of engagement in RMC or whether they were more engaged in care because of pre-existing health problems. Finally, to ensure sufficient power for outcome assessment, we chose to stratify age at the JHS cohort median. Therefore, inferences drawn from this dichotomous age categorization may be less informative than other age categories (e.g. young adult, elderly) which were not explicitly examined. Strengths of our study include the use of the Jackson Heart Study, a large, well-characterized cohort of African Americans, which is unique in its detailed measurements of psychosocial factors related to health.

Conclusion

Among African Americans with CKD or at increased risk of CKD, those who were younger, and males were more likely to report low use of RMC. Low trust was associated with low RMC use in all age groups. Differing barriers to engagement in RMC suggest assumptions should not be made about reasons for not seeking RMC among African Americans, as the rationale behind such behaviors are likely based on more than just self-reported race alone. Efforts to identify patients at risk of CKD incidence and progression in the settings they are most likely to receive care and efforts to address attitudes and perceptions which may hinder care represent important potential targets for future CKD prevention efforts.

Additional file

Table S1. Characteristics of participants included vs. those excluded from the analysis. (DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the staff and participants of the JHS.

Funding

The Jackson Heart Study (JHS) is supported and conducted in collaboration with Jackson State University (HHSN268201300049C and HHSN268201300050C), Tougaloo College (HHSN268201300048C), and the University of Mississippi Medical Center (HHSN268201300046C and HHSN268201300047C) contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CAD is supported by the Duke Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1TR001117).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The Jackson Heart Study but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of The Jackson Heart Study.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- ESRD

End stage renal disease

- RMC

Routine medical care

Authors’ contributions

CJD and LEB were involved in all aspects of this study, including study conceptualization, research analysis plan development, interpretation of study results, and manuscript preparation. CAD performed primary data analysis. JL, NB, JS, RH, CT, MS, TS, and NRP contributed to research analysis plan development, interpretation of study results, and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Each JHS participant provided written informed consent, and the institutional review boards at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson State University, and Tougaloo College approved the JHS study protocol.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hsu CY, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG. Racial differences in the progression from chronic renal insufficiency to end-stage renal disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(11):2902–2907. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000091586.46532.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Renal Data System: USRDS 2014 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, 2014 [http://www.usrds.org].

- 3.Mehrotra R, Kermah D, Fried L, Adler S, Norris K. Racial differences in mortality among those with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1403–1410. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal V, Jaar BG, Frisby XY, Chen SC, Qiu Y, Li S, Whaley-Connell AT, McCullough PA, Bomback AS. Access to health care among adults evaluated for CKD: findings from the kidney early evaluation program (KEEP) Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(3 Suppl 2):S5–15. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans K, Coresh J, Bash LD, Gary-Webb T, Kottgen A, Carson K, Boulware LE. Race differences in access to health care and disparities in incident chronic kidney disease in the US. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(3):899–908. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, Vranizan K, Stewart AL. Primary care and receipt of preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(5):269–276. doi: 10.1007/BF02598266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbie-Smith G, Flagg EW, Doyle JP, O'Brien MA. Influence of usual source of care on differences by race/ethnicity in receipt of preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(6):458–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiscella K, Holt K, Meldrum S, Franks P. Disparities in preventive procedures: comparisons of self-report and Medicare claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:122. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulware LE, Carson KA, Troll MU, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Perceived susceptibility to chronic kidney disease among high-risk patients seen in primary care practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1123–1129. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1086-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greer RC, Cooper LA, Crews DC, Powe NR, Boulware LE. Quality of patient-physician discussions about CKD in primary care: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(4):583–591. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waterman AD, Browne T, Waterman BM, Gladstone EH, Hostetter T. Attitudes and behaviors of African Americans regarding early detection of kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4):554–562. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuot DS, Plantinga LC, Hsu C-Y, Jordan R, Burrows NR, Hedgeman E, Yee J, Saran R, Powe NR. Chronic kidney disease awareness among individuals with clinical markers of kidney dysfunction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):1838–1844. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00730111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flessner MF, Wyatt SB, Akylbekova EL, Coady S, Fulop T, Lee F, Taylor HA, Crook E. Prevalence and awareness of CKD among African Americans: the Jackson heart study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(2):238–247. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuqua SR, Wyatt SB, Andrew ME, Sarpong DF, Henderson FR, Cunningham MF, Taylor HA., Jr Recruiting African-American research participation in the Jackson heart study: methods, response rates, and sample description. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor HA, Jr, Wilson JG, Jones DW, Sarpong DF, Srinivasan A, Garrison RJ, Nelson C, Wyatt SB. Toward resolution of cardiovascular health disparities in African Americans: design and methods of the Jackson heart study. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes--2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang Y, Castro AF, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sims M, Wyatt SB, Gutierrez ML, Taylor HA, Williams DR. Development and psychometric testing of a multidimensional instrument of perceived discrimination among African Americans in the Jackson heart study. Ethn. Dis. 2009;19(1):56–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberger C, Krasner S, Solomon E. Health psychology: individual differences and stress. New York: Springer Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payne TJ, Wyatt SB, Mosley TH, Dubbert PM, Guiterrez-Mohammed ML, Calvin RL, Taylor HA, Jr, Williams DR. Sociocultural methods in the Jackson heart study: conceptual and descriptive overview. Ethn. Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebreab SY, Diez-Roux AV, Hickson DA, Boykin S, Sims M, Sarpong DF, Taylor HA, Wyatt SB. The contribution of stress to the social patterning of clinical and subclinical CVD risk factors in African Americans: the Jackson heart study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(9):1697–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheatham CT, Barksdale DJ, Rodgers SG. Barriers to health care and health-seeking behaviors faced by Black men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(11):555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bromley EG, May FP, Federer L, Spiegel BM, van Oijen MG. Explaining persistent under-use of colonoscopic cancer screening in African Americans: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2015;71:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popescu I, Duffy E, Mendelsohn J, Escarce JJ. Racial residential segregation, socioeconomic disparities, and the white-Black survival gap. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross JS, Bernheim SM, Bradley EH, Teng HM, Gallo WT. Use of preventive care by the working poor in the United States. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okoro CA, Zhao G, Dhingra SS, Xu F. Lack of health insurance among adults aged 18 to 64 years: findings from the 2013 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E231. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stark Casagrande S, Cowie CC. Health insurance coverage among people with and without diabetes in the U.S. adult population. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(11):2243–2249. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammond WP, Matthews D, Corbie-Smith G. Psychosocial factors associated with routine health examination scheduling and receipt among African American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(4):276–289. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30600-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi L, Chen CC, Nie X, Zhu J, Hu R. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in access to primary care among people with chronic conditions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(2):189–198. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.130246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grumbach K, Keane D, Bindman A. Primary care and public emergency department overcrowding. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(3):372–378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powell W, Adams LB, Cole-Lewis Y, Agyemang A, Upton RD. Masculinity and race-related factors as barriers to health help-seeking among African American men. Behav Med. 2016;42(3):150–163. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2016.1165174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beydoun MA, Poggi-Burke A, Zonderman AB, Rostant OS, Evans MK, Crews DC. Perceived discrimination and longitudinal change in kidney function among urban adults. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(7):824–834. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuffee YL, Hargraves JL, Rosal M, Briesacher BA, Schoenthaler A, Person S, Hullett S, Allison J. Reported racial discrimination, trust in physicians, and medication adherence among inner-city African Americans with hypertension. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):e55–e62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elder K, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Wiltshire J, Piper C, Horn WS, Gilbert KL, Hullett S, Allison J. Trust, medication adherence, and hypertension control in southern African American men. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):2242–2245. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hood KB, Hart A, Jr, Belgrave FZ, Tademy RH, Jones RA. The role of trust in health decision making among African American men recruited from urban barbershops. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104(7–8):351–359. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musa D, Schulz R, Harris R, Silverman M, Thomas SB. Trust in the health care system and the use of preventive health services by older black and white adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(7):1293–1299. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheppard VB, Mays D, LaVeist T, Tercyak KP. Medical mistrust influences black women's level of engagement in BRCA 1/2 genetic counseling and testing. J Natl Med Assoc. 2013;105(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30081-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammond WP, Matthews D, Mohottige D, Agyemang A, Corbie-Smith G. Masculinity, medical mistrust, and preventive health services delays among community-dwelling African-American men. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1300–1308. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobs EA, Rolle I, Ferrans CE, Whitaker EE, Warnecke RB. Understanding African Americans' views of the trustworthiness of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):642–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong K, Putt M, Halbert CH, Grande D, Schwartz JS, Liao K, Marcus N, Demeter MB, Shea JA. Prior experiences of racial discrimination and racial differences in health care system distrust. Med Care. 2013;51(2):144–150. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827310a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Persky S, Kaphingst KA, Allen VC, Jr, Senay I. Effects of patient-provider race concordance and smoking status on lung cancer risk perception accuracy among African-Americans. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(3):308–317. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9475-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997–1004. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schoenthaler A, Montague E, Baier Manwell L, Brown R, Schwartz MD, Linzer M. Patient-physician racial/ethnic concordance and blood pressure control: the role of trust and medication adherence. Ethn Health. 2014;19(5):565–578. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2013.857764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albright K, Richardson T, Kempe KL, Wallace K. Toward a trustworthy voice: increasing the effectiveness of automated outreach calls to promote colorectal cancer screening among African Americans. Perm J. 2014;18(2):33–37. doi: 10.7812/TPP/13-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin KD, Roter DL, Beach MC, Carson KA, Cooper LA. Physician communication behaviors and trust among black and white patients with hypertension. Med Care. 2013;51(2):151–157. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827632a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okhomina VI, Glover L, Taylor H, Sims M. Dimensions of and responses to perceived discrimination and subclinical disease among African-Americans in the Jackson heart study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(5):1084–1092. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Mani N, Halterman JS. Dependence on emergency care among young adults in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):663–669. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1313-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Halterman JS. Ambulatory care among young adults in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(6):379–385. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hargreaves DS, James D, Goddings AL, McVey D, Viner RM. Distinct patterns of health engagement among adolescents and young adults in England: implications for health services. Perspect Public Health. 2014;134(2):81–84. doi: 10.1177/1757913913519770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson HM, Thorpe CT, Bartels CM, Schumacher JR, Palta M, Pandhi N, Sheehy AM, Smith MA. Undiagnosed hypertension among young adults with regular primary care use. J Hypertens. 2014;32(1):65–74. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson HM, Olson AG, LaMantia JN, Kind AJ, Pandhi N, Mendonca EA, Craven M, Smith MA. Documented lifestyle education among young adults with incident hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Gooding HC, McGinty S, Richmond TK, Gillman MW, Field AE. Hypertension awareness and control among young adults in the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(8):1098–1104. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2809-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferris ME, Cuttance JR, Javalkar K, Cohen SE, Phillips A, Bickford K, Gibson K, Ferris MT, True K. Self-management and transition among adolescents/young adults with chronic or end-stage kidney disease. Blood Purif. 2015;39(1–3):99–104. doi: 10.1159/000368978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Owen WF, Jr, Chertow GM, Lazarus JM, Lowrie EG. Dose of hemodialysis and survival: differences by race and sex. JAMA. 1998;280(20):1764–1768. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bleyer AJ. Race and dialysis survival. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(4):879–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Norris KC. Racial survival paradox of dialysis patients: robust and resilient. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(2):182–185. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.02.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimmel PL, Fwu CW, Eggers PW. Segregation, income disparities, and survival in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(2):293–301. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Lessler J, Hall EC, James N, Massie AB, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Association of race and age with survival among patients undergoing dialysis. JAMA. 2011;306(6):620–626. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johns TS, Estrella MM, Crews DC, Appel LJ, Anderson CA, Ephraim PL, Cook C, Boulware LE. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, race, and mortality in young adult dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(11):2649–2657. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Characteristics of participants included vs. those excluded from the analysis. (DOCX 19 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The Jackson Heart Study but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of The Jackson Heart Study.