Abstract

Objective

More than a third of the U.S. population of older adults is obese. The present study tests the Dyadic Biopsychosocial Model of Marriage and Health, which hypothesizes that, among married couples, individual and partner chronic stress predicts increased waist circumference and these links are exacerbated in negative quality marriages.

Method

Participants were from the nationally representative longitudinal Health and Retirement Study (HRS). A total of 2,042 married individuals (in 1,098 married couples) completed psychosocial and waist circumference assessments in 2006 and 2010. Analyses examined whether negative marital quality and chronic stress in Wave 1 (2006) were associated with changes in waist circumference over time.

Results

Actor–partner interdependence models revealed that greater partner stress, rather than individuals’ own reports of stress, was associated with increased waist circumference over time. Higher perceived negative marital quality among husbands and lower negative marital quality among wives exacerbated the positive link between partner stress and waist circumference.

Discussion

Consistent with the Dyadic Biopsychosocial Model of Marriage and Health, partner stress has direct associations with waist circumference among couples and this link is moderated by negative marital quality. Thus, dyadic perceptions of stress and negative marital quality are important to consider for understanding marriage and obesity.

Keywords: Couples, Negative marital quality, Stress, Waist circumference

In 2007–2010, more than a third of the U.S. population of older adults was obese (Fakhouri, Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). These figures are expected to continue increasing, as successive cohorts are becoming obese at younger ages (Lee et al., 2010), and this is especially problematic given that obesity is associated with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer (breast, colon, kidney, and esophageal), and osteoarthritis (Rigby, Leach, Lobstein, Huxley, & Kumanyika, 2009) as well as negative psychosocial factors, such as depression, loneliness, and isolation (Newman, 2009).

Obesity is inextricably linked with the social context, and perhaps one of the most influential social contexts is marriage. Poor marital quality predicts weight gain (Kershaw et al., 2014; Robles, Slatcher, Trombello, & McGinn, 2014; Troxel, Matthews, Gallo, & Kuller, 2005), and this link is often stronger among women (Whisman & Uebelacker, 2012; Whisman, Uebelacker, & Settles, 2010). Poor marital quality may be particularly detrimental for weight gain when individuals are under stress. Indeed, couples are influenced by not only their own stress levels but also those of their partner, and stress is particularly harmful among couples who have conflicted or negative ties (Neff & Karney, 2007). Research on individuals (not married couples) shows that chronic or prolonged stress is associated with weight gain (Block, He, Zaslavsky, Ding, & Ayanian, 2009).

Research concerning the link between marriage and weight has typically focused on marital satisfaction. However, negative marital quality—defined as the extent to which one’s partner is critical, disappointing, irritating, and/or demanding (Walen & Lachman, 2000)—is more highly predictive of health than positive aspects of the tie (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2015; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Liu & Waite, 2014), and negative marital quality exacerbates the effects of stress on health (Birditt & Antonucci, 2008; Birditt, Newton, Cranford, & Ryan, 2015). Indeed, emerging research shows that stress and negative marital relationship quality interact and are associated with the health and well-being of both members of the couple (i.e., both actor and partner effects; Carr, Cornman, & Freedman, 2016; Birditt et al., 2015; Robles et al., 2014). Yet, we know little about the interactive effects of chronic stress exposure and negative marital quality on obesity among married couples.

Furthermore, we know little about the effects of marital quality and stress on waist circumference, an estimate of central adiposity, which is often more highly predictive of negative health outcomes than body mass index (Huxley, Mendis, Zheleznyakov, Reddy, & Chan, 2010; Lee, Huxley, Wildman, & Woodward, 2008). Excess abdominal fat (Klein et al., 2007), often indicated by greater waist circumference, is considered a cardiometabolic risk factor and is highly associated with morbidity and mortality (Huxley et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2008). Thus, the purpose of the present study is to examine links between chronic stress exposure, negative marital quality, and waist circumference over time among older married couples and to assess how these associations vary by gender.

Theoretical Framework

This study draws on the Dyadic Biopsychosocial Model of Marriage and Health (Birditt, Newton, & Hope, 2014; Birditt et al., 2015), which incorporates aspects of three complementary models: the direct effects model, the stress-buffering model, and biopsychosocial theory. The Dyadic Biopsychosocial Model of Marriage and Health provides an integrative framework for understanding the marriage–health link among couples. The model hypothesizes that, consistent with direct effect theories of relationships and health (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Seeman, 1996), greater negative marital quality and chronic stress—as reported by both the individual and their partner—will be associated with increased waist circumference. In addition, the stress-buffering model hypothesizes that relationship quality is particularly influential under stressful life circumstances (Cohen & Wills, 1985) and that negative marital quality may exacerbate the link between stress and health outcomes. Thus, according to the model, links between individual and partner reports of stress and waist circumference are exacerbated by both individual and partner reports of negative marital quality.

Finally, the biopsychosocial model of health indicates that social (e.g., marital quality) and psychological factors (e.g., stress) influence overall health via behavioral and biological pathways (Lindau, Laumann, Levinson, & Waite, 2003; Seeman, 1996). Waist circumference is an indicator of central adiposity that represents a potential biological pathway through which marriage and stress may influence overall health and mortality.

Chronic Stress and Waist Circumference

The present study focuses on chronic rather than acute stress because stress that is long-lasting tends to be more damaging to health (Juster, McEwen, & Lupien, 2010; Thoits, 2010). Chronic stress is defined as an ongoing circumstance occurring for a year or longer that threatens to overwhelm an individual’s resources, including for example, ongoing financial problems, problems at work, or long-term caregiving. Chronic stress most likely has a stronger effect on waist circumference than short-term stress as it takes time to experience significant changes in central adiposity (Kershaw et al., 2014). Several studies have shown that chronic stress is associated with increased visceral fat accumulation (Björntorp, 1991, 2001; Marniemi et al., 2002). A recent meta-analysis showed a positive association between stress and adiposity, and the effects were stronger for men compared to women (Wardle, Chida, Gibson, Whitaker, & Steptoe, 2011). The current study contributes to the literature by examining the implications of both individual and partner reports of stress for waist circumference among couples.

Negative Marital Relationship Quality and Waist Circumference

Research on relationship quality in general reveals important links between negative relationship quality and increased waist circumference. Kouvonen and colleagues (2011) found that higher exposure to negative aspects of close relationships (defined as adverse exchanges and conflict) were associated with increased waist circumference. Similarly, Kershaw and colleagues (2014) found that chronically high negative ties with family and friends, and increases in negativity, were associated with increased waist circumference over a 10-year period among people aged 33–45 years.

Studies of marital quality in particular have revealed inconsistent findings concerning the association between marital quality and weight. For example, research on newlyweds suggests that couples who report greater marital satisfaction (i.e., positive marital quality) relax their efforts to maintain their weight (Meltzer, Novak, McNulty, Butler, & Karney, 2013). Yet, some studies have found few associations between marital relationship quality and weight (Sobal et al., 2009), whereas others found that severe obesity is associated with greater family strain (Carr & Friedman, 2006). In contrast, studies of metabolic syndrome (elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, and elevated fasting glucose) among middle-aged individuals have shown marital distress (a combination of low positive and high negative quality) predicted increased likelihood of having metabolic syndrome among women but not among men. Whisman and Uebelacker (2012) also found that greater marital distress among husbands predicted increased metabolic syndrome among wives, but there were no effects of wives’ distress on husbands’ metabolic syndrome.

Moderating Role of Negative Marital Quality on the Stress–Waist Circumference Link

According to the Dyadic Biopsychosocial Model of Marriage and Health, the link between stress and waist circumference may be particularly strong when couples are experiencing increased negative marital quality. However, few studies have examined how marital relationship quality can moderate the associations between stress and weight or waist circumference. Studies have examined the moderating role of marital quality for other biological indicators such as blood pressure and found that negative marital quality moderates the effects of stress on health among couples (Birditt et al., 2014, 2015). For example, Birditt and colleagues (2015) found that among older couples, wives’ stress was associated with increased blood pressure among husbands who reported greater negative marital quality.

Other Factors Associated With Waist Circumference

We consider a number of covariates that have been linked to waist circumference including years of education, age, number of children, and race. Specifically, research shows that greater waist circumference is associated with lower levels of education (Hermann et al., 2011), increased age (Stevens, Katz, & Huxley, 2010), greater number of children in a family (Gunderson et al., 2004), and being Caucasian (Elobeid, Desmond, Thomas, Keith, & Allison, 2007). We also consider key characteristics of the marriage including marital order (remarried vs. first marriage) and length of marriage as covariates.

Present Study

The present study contributes to the literature by examining associations between chronic stress exposure, negative marital quality, and waist circumference among older couples over time, and the moderating role of negative marital quality on the stress–waist circumference link. We tested the following hypotheses: (a) Greater chronic stress exposure and negative marital quality (reported by individuals and partners) will be directly associated with increased waist circumference and (b) negative marital quality (reported by individuals and partners) will exacerbate the link between chronic stress (reported by individuals and partners) and waist circumference. Because the literature is inconsistent regarding gender differences in the effects of negative marital quality and stress on waist circumference (and related measures), we do not make specific hypotheses about gender.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative multiwave longitudinal study of over 20,000 individuals aged 50 and older. The sample design involves interviewing individuals and their spouses or live-in partners every 2 years. Since 2006, a portion of the HRS interview referred to as the enhanced face-to-face interview began, and data are obtained biennially from a random sample of 50% of the panel participants. The enhanced face-to-face interview includes a comprehensive battery of physical assessments and a self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) that includes questions about the spousal/partner relationship and chronic stress (Smith et al., 2013). The SAQ was left with the respondents at the end of the face-to-face interview, and respondents were asked to complete and mail it back to the main field office at the University of Michigan. Because the enhanced face-to-face interview is conducted with 50% of the sample every 2 years, the 2010 wave provided the first longitudinal biological and psychosocial data from the 2006 participants. Thus, in the present study, we included two waves of data: 2006 and 2010.

The response rate for the 2006 enhanced face-to-face interview was 82% and the response rate for the 2006 SAQ was 90% (Smith et al., 2013). In 2010, individuals who completed the 2006 wave were contacted again (response rate = 78% for the SAQ). For the present analysis, we focused on married couples who completed the SAQ and waist circumference measures in both 2006 and 2010 (see Supplementary Figure 1 for a complete description of participant inclusion/exclusion).

We compared our analytic (N = 2,042) sample to married individuals who completed the 2006 SAQ but were not included either because they divorced, had missing data, or did not complete the SAQ in 2010 (N = 2,104). Overall, the analytic sample was younger, healthier, had more years of education, was more likely to be White, and reported less chronic stress and lower negative marital quality than the married participants who were not included.

Table 1 includes descriptive statistics for the analytic sample. Mean ages for the sample of husbands and wives were 63 (SE = 0.26) and 62 years (SE = 0.25), respectively. Ninety-two percent of husbands and 94% of wives were White, and 3% of husbands and wives were Black. Husbands had an average of 14 years and wives an average of 13 years of education. Couples were married for an average of 34 years (SE = 0.30). Thus, the sample is limited in that it is not representative of all older married couples in the United States, but it does provide important initial information that can be pursued among more diverse samples.

Table 1.

Description of Study Variables

| Study variables | Husbands (n = 1,067) | Wives (n = 975) | t/χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SE) | 63.31 (0.26) | 62.06 (0.25) | 22.75*** |

| Education (M, SE) | 13.71 (0.08) | 13.47 (0.08) | 3.85*** |

| Years married (M, SE) | 34.01 (0.30) | 34.01 (0.30) | — |

| Race (% White) | 92.48 | 94.49 | 674.08*** |

| % Black | 3.35 | 3.05 | — |

| Number of children (M, SE) | 2.91 (0.04) | 2.91 (0.04) | — |

| First marriage (%) | 66.65 | 71.72 | 444.30*** |

| Remarriage (%) | 33.35 | 28.28 | — |

| Waist circumference | |||

| Wave 1 (M, SE) | 41.68 (0.16) | 37.35 (0.20) | 19.20*** |

| Wave 2 (M, SE) | 42.23 (0.17) | 38.03 (0.19) | 18.60*** |

| Increase by 10% | 6.91 | 13.70 | 0.12 |

| Chronic stress exposure | |||

| Wave 1 (M, SE) | 1.54 (0.04) | 1.61 (0.05) | −1.93 |

| Negative marital quality | |||

| Wave 1 (M, SE) | 1.88 (0.02) | 1.97 (0.02) | −2.72** |

Notes: Values are weighted % or weighted mean (SE).

**p < .01, ***p < .001.

Measures

Waist circumference

In Waves 1 (2006) and 2 (2010), respondents were asked to stand, point to their navel, and place a tape measure around their waist at the level of their navel (Crimmins et al., 2008). Similar to previous studies, waist circumference was measured once per study wave (Kershaw et al., 2014). Interviewers were instructed to enter respondents’ waist measurement to the nearest quarter inch. Thus, the waist circumference variable represents the number of inches to the nearest quarter inch. Waist circumference assessed by interviewers using similar methods has been demonstrated to be reliable across measures and interviewers (Klein et al., 2007).

Chronic stress exposure

In Wave 1 (2006), participants completed seven items regarding chronic stressors (Troxel, Matthews, Bromberger, & Sutton-Tyrrell, 2003). Participants were asked whether any of the following were current and ongoing problems that had lasted 12 months or longer and to indicate how upsetting each had been: physical or emotional problems (in spouse or child); problems with alcohol or drug use of a family member; difficulties at work; financial strain; housing problems; problems in a close relationship; and helping at least one sick, limited, or frail family member or friend on a regular basis. For each item, participants received the following response choices: 1 = No, didn’t happen; 2 = Yes, but not upsetting; 3 = Yes, somewhat upsetting; and 4 = Yes, very upsetting. To create a summary measure of exposure to chronic stress, responses were recoded as 1 (Yes the stressor happened: scores 2–4) or 0 (No it did not happen) and summed across items. Due to the positive skew in the distribution, scores were truncated so that they ranged from 0 to 5 or more. The most frequent problems reported in Wave 1 included an ongoing health problem of spouse or child (39%), helping at least one sick or disabled person (35%) and ongoing financial strain (32%).

Negative marital quality

In Wave 1 (2006), participants completed four widely used and validated items assessing the negative qualities of the marital relationship (Schuster, Kessler, & Aseltine, 1990; Walen & Lachman, 2000): How often does your spouse 1) make too many demands on you, 2) criticize you, 3) let you down when you are counting on them, and 4) get on your nerves? Response options ranged from 1 (A lot) to 4 (Not at all); all items were reverse-coded so that higher scores indicated higher negative marital quality. We created negative marital quality scores for both husband and wife in Wave 1 by averaging the four items (husbands: α = .76, wives: α = .77).

Covariates

Years of education, gender, years married, age, marital order, number of children, and race from the Wave 1 data were included as covariates. Education, years married, number of children, and age were continuous variables; race was coded as 1 (White) or 0 (Not White); gender was coded as 1 (Female) or 0 (Male); and marital order was coded as 1 (first marriage) or 0 (second or subsequent marriage).

Analysis Strategy

First, descriptive analyses of chronic stress exposure, negative marital quality, and waist circumference were conducted. Next, we conducted an examination of differences between husbands and wives for these measures and whether waist circumference changed over time with paired t tests. Hypotheses were tested using actor–partner interdependence models (APIMs; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) and estimated with multilevel modeling (SAS PROC MIXED). The APIM specifies two parts to the association between predictor and outcome: the actor effect, which describes the unique effect of a person’s own predictor on his or her (the actor’s) own outcome, and the partner effect, which describes the unique effect of their partner’s predictor on the actor’s outcome. The multilevel models had two levels: Level 1 referred to individuals and Level 2 referred to the couple. All models controlled for Wave 1 waist circumference (of both actor and partner), education, number of years married, marital order, number of children, race, gender, and age. All continuous variables were grand mean-centered, and all categorical variables were effect-coded (−1, 1) before entering them in the models. The centered variables were used to create the interaction terms, which also reduce potential multicollinearity issues.

To test the research hypotheses, we estimated a series of three models. Model 1 examined whether waist circumference reported in Wave 2 varied by Wave 1 actor and partner reports of chronic stress and Wave 1 actor and partner reports of negative marital quality. Model 2 included two-way interactions between Wave 1 chronic stress exposure and Wave 1 negative marital quality to assess whether negative marital quality moderated the chronic stress exposure–waist circumference link. This included testing the following interactions: actor stress × actor negative, actor stress × partner negative, partner stress × actor negative, and partner stress × partner negative. Model 3 included all two- and three-way interactions among stress, negative marital quality, and gender to assess whether the effects of chronic stress exposure and negative marital quality on waist circumference varied by gender. We explored significant interactions with graphs and tests of simple slopes in which the estimates from the multilevel models were used to plot waist circumference as a function of low and high levels of stress and negative marital quality. Low was defined as 1 SD below the mean and high as 1 SD above the mean. We assessed whether there was a significant difference between the fit of the three models by subtracting the −2 log likelihood estimations of models and examining differences on a chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equaling the change in number of parameters (Singer & Willett, 2003).

To further explore significant effects, we estimated binomial multilevel models using the glimmix macro in SAS to examine whether chronic stress and negative marital quality were associated with a 10% or greater increase in waist circumference between 2006 and 2010 (1 = yes an increase by 10% or more; 0 = no such increase).

Because not all participants were asked to complete the SAQ, the HRS team created a SAQ weight to adjust for sample selection. The HRS recommends that when analyzing data from the SAQ, researchers use the weight to account for the complex sample structures. Thus, before conducting the analyses, all data were weighted with the SAQ weight that incorporates the HRS respondent-level weight and a nonresponse adjustment factor (additional details are provided in Smith et al., 2013).

Results

Descriptives

Overall, couples reported relatively low levels of chronic stress exposure and negative marital quality (Table 1). Paired t tests revealed that wives reported greater negative marital quality compared to husbands, and there was no significant gender difference in chronic stress exposure. Husbands had higher waist circumference than wives in both waves, and waist circumference increased significantly over time among both husbands (t = 7.33, p < .001) and wives (t = 6.90, p < .001). According to waist circumference thresholds for increased risk of obesity and disease (35+ inches for women; 40+ inches for men; Rigby et al., 2009), 59% of the husbands and 64% of the wives were at increased risk of disease in Wave 1, whereas 66% of husbands and 70% of wives were at increased risk in Wave 2.

Furthermore, a total of 188 people (9%) showed a 10% or greater increase in waist circumference, which represented an average increase of 4 inches or more over 4 years. Individuals in this group were most likely to transition from a healthy waist circumference to an unhealthy waist circumference (42%), followed by individuals who began with an unhealthy waist circumference and became worse (37%). The remaining 21% of individuals did not have an unhealthy waist circumference at either time point.

Bivariate correlations revealed that chronic stress exposure, negative marital quality, and waist circumference were moderately associated between husbands and wives within couples. In addition, husband and wife reports of chronic stress exposure and negative marital quality were directly associated with greater waist circumference in Waves 1 and 2 (see Supplementary Table 1).

Direct Effects of Chronic Stress and Negative Marital Quality

First, models were estimated to examine whether individual and partner chronic stress exposure and negative marital quality were associated with waist circumference in Wave 2, controlling for waist circumference in Wave 1 (Table 2; Model 1). There was a significant association between partner reports of Wave 1 stress and actor waist circumference, such that greater partner stress was associated with greater actor waist circumference over time for both men and women. The effect of actor reports of chronic stress on their own waist circumference was not significant. The model including all of the main effects of stress and negative marital quality did not improve in fit compared to the model with only covariates. However, when we estimated a model with only partner stress as the added predictor, the model fit did improve (Δ −2 log likelihood = 5.3, df = 1, p < .05) compared to the model with only the covariates.

Table 2.

Multilevel Models Examining WC as a Function of Chronic Stress Exposure, NMQ, and Gender (N = 2,042)

| Predictor variables | Model 1: direct effects of stress and NMQ | Model 2: moderating role of NMQ on stress–WC link | Model 3: do the effects vary by gender? |

|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Actor stress | .00 (0.04) | .00 (0.05) | .01 (0.05) |

| Partner stress | .11 (0.05)* | .10 (0.05)* | .12 (0.05)* |

| Actor × partner stress | −.03 (0.03) | −.03 (0.03) | −.02 (0.03) |

| Actor NMQ | .02 (0.10) | .01 (0.11) | .02 (0.11) |

| Partner NMQ | −.05 (0.10) | −.06 (0.10) | −.03 (0.11) |

| Actor × partner NMQ | .12 (0.16) | .09 (0.18) | .06 (0.18) |

| Actor stress × actor NMQ | .02 (0.07) | .04 (0.07) | |

| Actor stress × partner NMQ | −.02 (0.08) | −.07 (0.08) | |

| Partner stress × actor NMQ | .02 (0.08) | .02 (0.09) | |

| Partner stress × partner NMQ | .06 (0.07) | .13 (0.08) | |

| Actor stress × gender | .01 (0.05) | ||

| Partner stress × gender | −.02 (0.05) | ||

| Actor stress × partner stress × gender | −.03 (0.03) | ||

| Actor NMQ × gender | −.16 (0.12) | ||

| Partner NMQ × gender | .26 (0.12)* | ||

| Actor NMQ × partner NMQ × gender | .18 (0.13) | ||

| Actor stress × actor NMQ × gender | .04 (0.07) | ||

| Actor stress × partner NMQ × gender | −.09 (0.08) | ||

| Partner stress × actor NMQ × gender | −.17 (0.08)* | ||

| Partner stress × partner NMQ × gender | .24 (0.07)** | ||

| −2 Log likelihood | 9,909.2 | 9,908.1 | 9,883.8 |

| Change in likelihood | 6.9 | 1.1 | 24.3** |

Notes: NMQ = negative marital quality; WC = waist circumference. Change in likelihood in Model 1 is based on comparison with a covariate-only model (9,916.1). Change in likelihood for Models 2 is change from Model 1 and for Model 3 is change from Model 2. Models controlled for Wave 1 waist circumference (of both actor and partner), education, number of years married, marital order, number of children, race, gender, and age.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

We explored the effect of partner stress further by estimating a model predicting a 10% or greater increase in waist circumference over time. Each unit increase in partner chronic stress exposure was associated with a 1.44 increased odds of experiencing a 10% or greater increase in actors’ waist circumference over 4 years.

Moderating Role of Negative Marital Quality on the Stress–Waist Circumference Link

Next, we examined the moderating effects of negative marital quality on the stress–waist circumference link. We included two-way interactions between chronic stress exposure and negative marital quality (Table 2; Model 2). There were no significant interactions between stress and negative marital quality predicting waist circumference.

Gender Differences in the Links Between Stress, Negative Marital Quality, and Waist Circumference

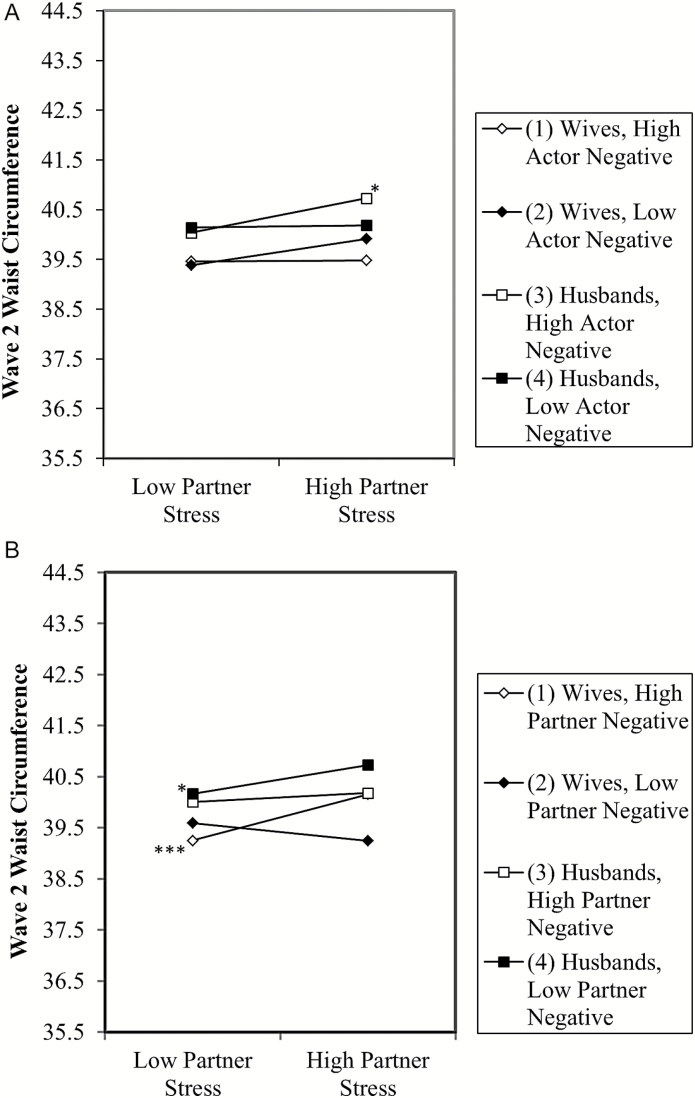

Next, we estimated a multilevel model that included interactions between gender, chronic stress exposure, and negative marital quality to examine whether there were gender differences in the associations between stress, negative marital quality, and waist circumference (Table 2; Model 3). There was a significant three-way interaction between partner reports of stress, actor reports of negative marital quality, and gender. Tests of the simple slopes indicated wives’ chronic stress exposure was associated with increased waist circumference among husbands when husbands reported greater negative marital quality (Figure 1A; b = .25, p < .05). None of the other simple slopes were significant.

Figure 1.

(A) Predicted waist circumference in Wave 2 at 1 SD above and below the mean for partner stress and actor negative marital quality in Wave 1 (controlling for all covariates). The minimum waist circumference was 25 and the maximum was 78; y axis represents the 20th to the 80th percentile. *p < .05. The significant simple slope (Line 3) represents the link between wives’ stress and husbands’ waist circumference among husbands who reported high negative marital quality. (B) Predicted waist circumference in Wave 2 at one standard deviation above and below the mean for partner stress and partner negative marital quality in Wave 1 (controlling for all covariates). The minimum waist circumference was 25 and maximum was 78; the y axis represents the 20th to the 80th percentile. *p < .05, ***p < .001. The significant simple slopes included Line 1 that represents the link between husbands’ stress and wives’ waist circumference among couples in which husbands reported high negative marital quality and Line 4 that represents the link between wives’ stress and husbands’ waist circumference among couples in which wives reported low negative marital quality.

There was also a significant three-way interaction between partner reports of chronic stress exposure, partner reports of negative marital quality, and gender. Tests of the simple slopes indicated that husbands’ chronic stress exposure was associated with increased waist circumference among wives when husbands reported greater negative marital quality (b = .32, p < .001; Figure 1B). Also, wives’ chronic stress exposure was associated with increased waist circumference among husbands when wives reported low negative marital quality (b = .20, p < .05).

We examined the interactions further by predicting a 10% or greater increase in waist circumference. Consistent with the previous analysis, there was a significant three-way interaction between partner reports of chronic stress exposure, partner reports of negative marital quality, and gender. Tests of the simple slopes revealed that wives had a 1.69 greater odds of experiencing a 10% increase in waist circumference over time when their husbands reported greater chronic stress exposure and greater negative marital quality (b = .52, p < .001). In contrast, husbands had a 2.17 greater odds of experiencing a 10% increase in their waist circumference when wives reported greater chronic stress and lower negative marital quality (b = .77, p < .001).

Post Hoc Analyses

First, we considered a variety of ways of conceptualizing stress. For instance, models examining stressor types (interpersonal vs. noninterpersonal) revealed the same pattern of findings. We estimated additional models controlling for the chronic stress exposure as reported by the actor and partner in Wave 2, and neither were associated with waist circumference.

We conducted a series of analyses to assess whether waist circumference at Wave 1 was associated with changes in negative marital quality or chronic stress exposure. Greater waist circumference of the partner at Wave 1 was associated with increased stress among individuals, providing some evidence of bidirectional associations between partner stress exposure and waist circumference. However, waist circumference at Wave 1 was not associated with changes in negative marital quality.

Discussion

Consistent with the Dyadic Biopsychosocial Model of Marriage and Health, the health of married individuals is affected by the marital context. Partners’ reports of chronic stress exposure, rather than individuals’ own reports of stress, were associated with increased waist circumference over time for both husbands and wives. Furthermore, higher negative marital quality among husbands and lower negative marital quality among wives exacerbated the association between their partner’s chronic stress exposure and their own waist circumference.

Chronic Stress Exposure and Waist Circumference Among Married Couples

Greater chronic stress exposure reported by partners (and not stress reported by the actor/individual) was associated with increased waist circumference over time among married couples. This finding is similar to the conclusions of a recent meta-analysis (Wardle et al., 2011): that stress predicts increased adiposity. However, the present study showed that among married couples it is the partners’ reports—not those of the individual—that are important for waist circumference. Thus, previous studies that have focused on stress reported by individuals might have overlooked sources of stress that have important implications for health.

It is unclear how partner stress influences the waist circumference of individuals. Stress may be communicated among couples in ways that individuals find distressing, especially when the stress is chronic. Likewise, spouses may feel obligated to provide support when their spouse is under stress, and in turn feel that their own needs are not being met. It is also likely that older couples have a great deal of interdependence due to the number of years they have been together. The marital literature has long suggested that stress is a dyadic phenomenon and that spouses do not experience stress independently but as a couple (Bodenmann, Ledermann, & Bradbury, 2007). Indeed, previous research on married couples reveals that partner stress is associated with increased blood pressure among husbands (Birditt et al., 2015). Research also suggests that individuals who are stressed may prefer high-fat foods or exercise less, which may have important implications for waist circumference (Wardle et al., 2011). More detailed examination of these potential mechanisms is needed in future research.

Moderating Role of Negative Marital Quality on the Stress–Waist Circumference Link

Interestingly, there were consistent gender differences in the moderating effect of negative marital quality on the partner stress–waist circumference link. Wives’ greater chronic stress exposure was associated with increased waist circumference among husbands when husbands reported higher negative marital quality. Likewise, husbands’ greater chronic stress exposure was associated with increased waist circumference among wives when husbands reported higher negative marital quality. In contrast, wives’ greater chronic stress exposure was associated with increased waist circumference among husbands when wives’ reported lower negative marital quality. Thus, it appears that higher negative marital quality among husbands and lower negative marital quality among wives exacerbate the associations between partner chronic stress exposure and waist circumference.

The findings are similar with previous research that examined stress among older married couples. For example, in their study of older couples in the English Longitudinal Study, Whisman and Uebelacker (2012) found that husbands’ marital distress predicted increased metabolic syndrome among wives. However, inconsistent with our findings, they also found that there were no effects of wives’ distress on husbands’ metabolic syndrome. The present study takes these findings further by indicating that partner stress can be harmful for both husbands and wives, especially when husbands report higher negative marital quality and wives lower negative marital quality.

There are a number of potential explanations for our findings, with one being that husbands usually report lower negative marital quality than wives (Birditt et al., 2015), and thus, their reports of high marital negativity are less normative and a sign of greater strain in the marriage. Husbands may also communicate their negative feelings in ways that wives find more distressing, and ultimately, they have a greater impact on biological health outcomes such as waist circumference. Furthermore, because women tend to report more negative marital quality (Birditt et al., 2015), low levels of negative marital quality among wives may be non-normative and an indicator of a lack of investment in the marriage. Alternatively, husbands of wives who report low negative marital quality may be more connected, and therefore more sensitive, to the stress experienced by their wives, and so may take on the stress of their wives (evidenced by higher weight circumference). Additionally, reports of low negative marital quality by wives may be indicative of greater investment in the marriage, leading them to communicate their feelings of distress more freely with their husbands, which in turn results in a link between wives’ stress and their husbands’ waist circumference. Research also suggests that individuals in distressed marriages or who are stressed may eat more in order to feel more connected with one another or to reduce distress (Adam & Epel, 2007) and that feeling hungry in response to marital distress (or in this case high partner stress) may have a social and emotional function (Jaremka et al., 2015). Couples may also exercise less when they are stressed (Nomaguchi & Bianchi, 2004). Thus, future research should consider potential pathways in greater detail.

The present research has some limitations. First, the measure of stress is somewhat limited in scope. For example, due to potential confounds with the outcome, it did not include one’s own health problems as a stressor. Additionally, the two most frequent stressors were likely to have been experienced by partners (ongoing health problems in a spouse or child and helping at least one sick or disabled person), which may have increased the likelihood of finding partner stress effects. We also lack information regarding relationship processes that underlie the reports of partner chronic stress exposure and negative relationship quality. Future studies should consider more nuanced and extensive measures of interpersonal processes linked with stress and negative marital quality (e.g., conflict, coping strategies, support exchanges), especially given the importance of the dyadic and complex nature of the marital context (Carr, Freedman, Cornman, & Schwarz, 2014). In addition, we lack information regarding physiological processes associated with metabolism as well as data regarding food choices, which are important mechanisms that can explain the link between stress and waist circumference (e.g., Block et al., 2009; Jeffery & Rick, 2002). Furthermore, waist circumference was measured once per wave, but other studies include multiple measurements (Kershaw et al., 2014; Kouvonen et al., 2011). There is not a single standard approach, however, for assessing waist circumference in the literature (Klein et al., 2007). Moreover, due to incomplete data on key variables, the sample was reduced and may be less representative of the larger U.S. married older adult population. Research on more ethnically diverse samples as well as samples that are less healthy are needed to understand whether and how these findings generalize to other groups of married or partnered older adults.

The current study highlights the dyadic nature of marital relationship quality, stress, and their associations with waist circumference over time. These findings emphasize the need to examine the influence of both marital partners on individual health, particularly through the lens of gender, given that spouses are differentially influenced by their partners’ feelings and experiences of stress and negative marital quality. Individual reports of stress and relationship quality (in the absence of partner reports) provide an incomplete picture of the factors influencing waist circumference in the marital context, and we hope this study will lead to more research examining dyadic models of marriage and physical health.

Funding

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Angela Turkelson for her assistance with the statistical analyses.

References

- Adam T. C., & Epel E. S (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91, 449–458. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt K., & Antonucci T. C (2008). Life sustaining irritations? Relationship quality and mortality in the context of chronic illness. Social Science & Medicine, 67, 1291–1299. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt K. S. Newton N. J. Cranford J. A., & Ryan L. H (2015). Stress and negative relationship quality among older couples: Implications for blood pressure. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt K. S. Newton N., & Hope S (2014). Implications of marital/partner relationship quality and perceived stress for blood pressure among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 188–198. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björntorp P. (1991). Visceral fat accumulation: The missing link between psychosocial factors and cardiovascular disease?Journal of Internal Medicine, 230, 195–201. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björntorp P. (2001). Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities?Obesity Reviews, 2, 73–86. doi:10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J. P. He Y. Zaslavsky A. M. Ding L., & Ayanian J. Z (2009). Psychosocial stress and change in weight among US adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170, 181–192. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. Ledermann T., & Bradbury T. N (2007). Stress, sex, and satisfaction in marriage. Personal Relationships, 14, 551–569. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00171.x [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. Cornman J. C., & Freedman V. A (2016). Marital quality and negative experienced well-being: An assessment of actor and partner effects among older married persons. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 177–187. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. Freedman V. A. Cornman J. C., & Schwarz N (2014). Happy marriage, happy life? Marital quality and subjective well-being in later life. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76, 930–948. doi:10.1111/jomf.12133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., & Friedman M. A (2006). Body weight and the quality of interpersonal relationships. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69, 127–149. doi:10.1177/019027250606900202 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., & Wills T. A (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E. Guyer H. Langa K. Ofstedal M. B. Wallace R., & Weir D (2008). Documentation of physical measures, anthropometrics and blood pressure in the Health and Retirement Study. HRS Documentation Report DR-011, 14, 47–59. doi:10.7826/isr-um.06.585031.001.05.0014.2008 [Google Scholar]

- Elobeid M. A., Desmond R. A., Thomas O., Keith S. W., Allison D. B. (2007). Waist circumferences values are increasing beyond those expected from BMI increases. Obesity, 15, 2380–2383. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhouri T. H. Ogden C. L. Carroll M. D. Kit B. K., & Flegal K. M (2012). Prevalence of obesity among older adults in the United States, 2007–2010. NCHS Data Brief, 106, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson E. P. Murtaugh M. A. Lewis C. E. Quesenberry C. P. West D. S., & Sidney S (2004). Excess gains in weight and waist circumference associated with childbearing: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA). International Journal of Obesity, 28, 525–535. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann S. Rohrmann S. Linseisen J. May A. M. Kunst A. Besson H., … Peeters P. H. M (2011). The association of education with body mass index and waist circumference in the EPIC-PANACEA study. BMC Public Health, 11, 1–12. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. S. Landis K. R., & Umberson D (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241, 540–545. doi:10.1126/science.3399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley R. Mendis S. Zheleznyakov E. Reddy S., & Chan J (2010). Body mass index, waist circumference and waist:hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular risk—A review of the literature. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64, 16–22. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2009.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaremka L. M. Belury M. A. Andridge R. R. Lindgren M. E. Habash D. Malarkey W. B., & Kiecolt-Glaser J. K (2015). Novel links between troubled marriages and appetite regulation marital distress, ghrelin, and diet quality. Clinical Psychological Science, 4, 363–375. doi:10.1177/2167702615593714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery R. W., & Rick A. M (2002). Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between body mass index and marriage-related factors. Obesity Research, 10, 809–815. doi:10.1038/oby.2002.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster R. P. McEwen B. S., & Lupien S. J (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 2–16. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D. A. Kashy D. A., & Cook W. L (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw K. N. Hankinson A. L. Liu K. Reis J. P. Lewis C. E. Loria C. M., & Carnethon M. R (2014). Social relationships and longitudinal changes in body mass index and waist circumference: The coronary artery risk development in young adults study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179, 567–575. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser J. K. Jaremka L. Andridge R. Peng J. Habash D. Fagundes C. P., … Belury M. A (2015). Marital discord, past depression, and metabolic responses to high-fat meals: Interpersonal pathways to obesity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 52, 239–250. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser J. K., & Newton T. L (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S. Allison D. B. Heymsfield S. B. Kelley D. E. Leibel R. L. Nonas C., & Kahn R (2007). Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: A consensus statement from shaping America’s health. Obesity, 15, 1061–1067. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouvonen A. Stafford M. De Vogli R. Shipley M. J. Marmot M. G. Cox T., … Kivimäki M (2011). Negative aspects of close relationships as a predictor of increased body mass index and waist circumference: The Whitehall II study. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 1474–1480. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.300115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. M. Huxley R. R. Wildman R. P., & Woodward M (2008). Indices of abdominal obesity are better discriminators of cardiovascular risk factors than BMI: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61, 646–653. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. M. Pilli S. Gebremariam A. Keirns C. C. Davis M. M. Vijan S., … Gurney J. G (2010). Getting heavier, younger: Trajectories of obesity over the life course. International Journal of Obesity, 34, 614–623. doi:10.1038/ijo.2009.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau S. T. Laumann E. O. Levinson W., & Waite L. J (2003). Synthesis of scientific disciplines in pursuit of health: The interactive biopsychosocial model. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(Suppl. 3), S74–S86. doi:10.1353/pbm.2003.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., & Waite L (2014). Bad marriage, broken heart? Age and gender differences in the link between marital quality and cardiovascular risks among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55, 403–423. doi:10.1177/0022146514556893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marniemi J. Kronholm E. Aunola S. Toikka T. Mattlar C. E. Koskenvuo M., & Rönnemaa T (2002). Visceral fat and psychosocial stress in identical twins discordant for obesity. Journal of Internal Medicine, 251, 35–43. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.00921.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer A. L. Novak S. A. McNulty J. K. Butler E. A., & Karney B. R (2013). Marital satisfaction predicts weight gain in early marriage. Health Psychology, 32, 824–827. doi:10.1037/a0031593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff L. A., & Karney B. R (2007). Stress crossover in newlywed marriage: A longitudinal and dyadic perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 594–607. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00394.x [Google Scholar]

- Newman A. (2009). Obesity in older adults. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 14, 6. doi:10.3912/ojin.vol14no1man03 [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi K. M., & Bianchi S. M (2004). Exercise time: Gender differences in the effects of marriage, parenthood, and employment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 413–430. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00029.x [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, N., Leach, R., Lobstein, T., Huxley, R., & Kumanyika, S. (2009). Epidemiology and social impact of obesity. In G. Williams & G. Fruhbeck (Eds.), Obesity: Science to practice (pp. 21–41). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Robles T. F. Slatcher R. B. Trombello J. M., & McGinn M. M (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 140–187. doi:10.1037/a0031859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster T. L. Kessler R. C., & Aseltine R. H. Jr (1990). Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18, 423–438. doi:10.1007/bf00938116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T. E. (1996). Social ties and health: The benefits of social integration. Annals of Epidemiology, 6, 442–451. doi:10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J. D., & Willett J. B (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195152968.001.0001 [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. Fisher G. Ryan L. Clarke P. House J., & Weir D (2013). Psychosocial and lifestyle questionnaire, 2006–2010. Documentation Report Core Section LB. Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr. umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/HRS2006-2010SAQdoc.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J. Hanson K. L., & Frongillo E. A (2009). Gender, ethnicity, marital status, and body weight in the United States. Obesity, 17, 2223–2231. doi:10.1038/oby.2009.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. Katz E. G., & Huxley R. R (2010). Associations between gender, age and waist circumference. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64, 6–15. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2009.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(Suppl), S41–S53. doi:10.1177/0022146510383499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel W. M. Matthews K. A. Bromberger J. T., & Sutton-Tyrrell K (2003). Chronic stress burden, discrimination, and subclinical carotid artery disease in African American and Caucasian women. Health Psychology, 22, 300–309. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.3.300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel W. M. Matthews K. A. Gallo L. C., & Kuller L. H (2005). Marital quality and occurrence of the metabolic syndrome in women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165, 1022–1027. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.9.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walen H. R., & Lachman M. E (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17, 5–30. doi:10.1177/0265407500171001 [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J. Chida Y. Gibson E. L. Whitaker K. L., & Steptoe A (2011). Stress and adiposity: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obesity, 19, 771–778. doi:10.1038/oby.2010.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman M. A., & Uebelacker L. A (2012). A longitudinal investigation of marital adjustment as a risk factor for metabolic syndrome. Health Psychology, 31, 80–86. doi:10.1037/a0025671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman M. A. Uebelacker L. A., & Settles T. D (2010). Marital distress and the metabolic syndrome: Linking social functioning with physical health. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 367–370. doi:10.1037/a0019547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.